Tarzan the Invincible

Edgar Rice Burroughs

TARZAN

THE INVINCIBLE

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS

ACE BOOKS, INC.

1120 Avenue of the Americas

New York 36, N.Y.

This Ace edition follows the text of the first hard-cover

book edition, originally published in 1930.

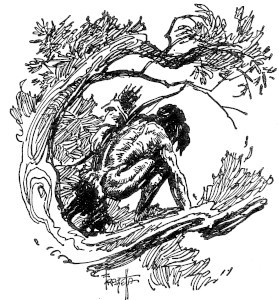

Cover art and title page illustration by Frank Frazetta.

Printed in U.S.A.

CONTEST OF JUNGLE CUNNING

A small band of white men encamped in the jungle, involved in some kind of expedition—seemingly innocuous, unimportant. But on the success or failure of their plan hung the destiny of Africa.

Only Tarzan could stop the mad machinations of Zveri and his fiercely determined comrades. But Tarzan would have to fight for his own life elsewhere, in the grim ruins of ancient Opar, whose strange priests were as fierce in their vengeance as its beautiful women were fierce in their love.

And Tarzan, lord of the jungle and all its creatures, would have to prove himself indeed invincible against the overwhelming odds of the most dangerous enemy—man.

FOREWORD

Master storyteller that he was, Edgar Rice Burroughs developed a variety of narrative techniques, applying different ones to different series of stories so that each series has a distinct "feel" of its own, not only in setting and characters, but in the very construction of the story and in the writing itself. For his Mars series, for instance, Burroughs began each story with a rather elaborate "frame" in which the story's hero was introduced. The hero then would tell the main story in the first person. The readers became so accustomed to this format that when one magazine published a Burroughs Mars story told in third person, there was an immediate uproar among the readers, and to this day many Burroughs fans challenge the authenticity of that story as Burroughs' own work!

For the Tarzan tales, Burroughs used a technique of introducing several sets of characters, starting each upon their own separate adventure, and then "cutting" from sequence to sequence in a style very much like that used in motion pictures. Skillfully drawing his characters together, Burroughs would finally reveal the grand pattern in which each element played its part.

In Tarzan the Invincible Burroughs applies this technique to three groups of protagonists. First are a band of communist agents provocateurs assembled from many lands and determined to stir rebellion in all of Africa. Second are the beautiful rival priestesses of fabled Opar, golden remnant of an ancient Atlantean colony. Third is Tarzan, lord of the jungle, who stands ready to face any challenge to his savage domain. Weaving these together in masterful fashion, Burroughs produces a tale of high adventure, spine-tingling action and suspense amidst colorful and exotic settings.

—Richard Lupoff

Editor, Xero, a fantasy

fiction fan magazine.

CONTENTS

| I | Little Nkima |

| II | The Hindu |

| III | Out of the Grave |

| IV | Into the Lion's Den |

| V | Before the Walls of Opar |

| VI | Betrayed |

| VII | In Futile Search |

| VIII | The Treachery of Abu Batn |

| IX | In the Death Cell of Opar |

| X | The Love of a Priestess |

| XI | Lost in the Jungle |

| XII | Down Trails of Terror |

| XIII | The Lion-Man |

| XIV | Shot Down |

| XV | "Kill, Tantor, Kill!" |

| XVI | "Turn Back!" |

| XVII | A Gulf That Was Bridged |

TARZAN THE INVINCIBLE

I

LITTLE NKIMA

I am no historian, no chronicler of facts, and, furthermore, I hold a very definite conviction that there are certain subjects which fiction writers should leave alone, foremost among which are politics and religion. However, it seems to me not unethical to pirate an idea occasionally from one or the other, provided that the subject be handled in such a way as to impart a definite impression of fictionizing.

Had the story that I am about to tell you broken in the newspapers of two certain European powers, it might have precipitated another and a more terrible world war. But with that I am not particularly concerned. What interests me is that it is a good story that is particularly well adapted to my requirements through the fact that Tarzan of the Apes was intimately connected with many of its most thrilling episodes.

I am not going to bore you with dry political history, so do not tax your intellect needlessly by attempting to decode such fictitious names as I may use in describing certain people and places, which, it seems to me, to the best interest of peace and disarmament, should remain incognito.

Take the story simply as another Tarzan story, in which, it is hoped, you will find entertainment and relaxation. If you find food for thought in it, so much the better.

Doubtless, very few of you saw, and still fewer will remember having seen, a news dispatch that appeared inconspicuously in the papers some time since, reporting a rumor that French Colonial Troops stationed in Somaliland, on the northeast coast of Africa, had invaded an Italian African colony. Back of that news item is a story of conspiracy, intrigue, adventure and love—a story of scoundrels and of fools, of brave men, of beautiful women, a story of the beasts of the forest and the jungle.

If there were few who saw the newspaper account of the invasion of Italian Somaliland upon the northeast coast of Africa, it is equally a fact that none of you saw a harrowing incident that occurred in the interior some time previous to this affair. That it could possibly have any connection whatsoever with European international intrigue, or with the fate of nations, seems not even remotely possible, for it was only a very little monkey fleeing through the tree tops and screaming in terror. It was little Nkima, and pursuing him was a large, rude monkey—a much larger monkey than little Nkima.

Fortunately for the peace of Europe and the world, the speed of the pursuer was in no sense proportionate to his unpleasant disposition, and so Nkima escaped him; but for long after the larger monkey had given up the chase, the smaller one continued to flee through the tree tops, screeching at the top of his shrill little voice, for terror and flight were the two major activities of little Nkima.

Perhaps it was fatigue, but more likely it was a caterpillar or a bird's nest that eventually terminated Nkima's flight and left him scolding and chattering upon a swaying bough, far above the floor of the jungle.

The world into which little Nkima had been born seemed a very terrible world, indeed, and he spent most of his waking hours scolding about it, in which respect he was quite as human as he was simian. It seemed to little Nkima that the world was populated with large, fierce creatures that liked monkey meat. There were Numa, the lion, and Sheeta, the panther, and Histah, the snake—a triumvirate that rendered unsafe his entire world from the loftiest tree top to the ground. And then there were the great apes, and the lesser apes, and the baboons, and countless species of monkeys, all of which God had made larger than He had made little Nkima, and all of which seemed to harbor a grudge against him.

Take, for example, the rude creature which had just been pursuing him. Little Nkima had done nothing more than throw a stick at him while he was asleep in the crotch of a tree, and just for that he had pursued little Nkima with unquestionable homicidal intent—I use the word without purposing any reflection upon Nkima. It had never occurred to Nkima, as it never seems to occur to some people, that, like beauty, a sense of humor may sometimes be fatal.

Brooding upon the injustices of life, little Nkima was very sad. But there was another and more poignant cause of sadness that depressed his little heart. Many, many moons ago his master had gone away and left him. True, he had left him in a nice, comfortable home with kind people, who fed him, but little Nkima missed the great Tarmangani, whose naked shoulder was the one harbor of refuge from which he could with perfect impunity hurl insults at the world. For a long time now little Nkima had braved the dangers of the forest and the jungle in search of his beloved Tarzan.

Because hearts are measured by content of love and loyalty, rather than by diameters in inches, the heart of little Nkima was very large—so large that the average human being could hide his own heart and himself, as well, behind it—and for a long time it had been just one great ache in his diminutive breast. But fortunately for the little Manu his mind was so ordered that it might easily be distracted even from a great sorrow. A butterfly or a luscious grub might suddenly claim his attention from the depths of brooding, which was well, since otherwise he might have grieved himself to death.

And now, therefore, as his melancholy thoughts returned to contemplation of his loss, their trend was suddenly altered by the shifting of a jungle breeze that brought to his keen ears a sound that was not primarily of the jungle sounds that were a part of his hereditary instincts. It was a discord. And what is it that brings discord into the jungle as well as into every elsewhere that it enters? Man. It was the voices of men that Nkima heard.

Silently the little monkey glided through the trees into the direction from which the sounds had come; and presently, as the sounds grew louder, there came also that which was the definite, final proof of the identity of the noise makers, as far as Nkima, or, for that matter, any other of the jungle folk, might be concerned—the scent spoor.

You have seen a dog, perhaps your own dog, half recognize you by sight; but was he ever entirely satisfied until the evidence of his eyes had been tested and approved by his sensitive nostrils?

And so it was with Nkima. His ears had suggested the presence of men, and now his nostrils definitely assured him that men were near. He did not think of them as men, but as great apes. There were Gomangani, Great Black Apes, negroes, among them. This his nose told him. And there were Tarmangani, also. These, which to Nkima would be Great White Apes, were white men.

Eagerly his nostrils sought for the familiar scent spoor of his beloved Tarzan, but it was not there—that he knew even before he came within sight of the strangers.

The camp upon which Nkima presently looked down from a nearby tree was well established. It had evidently been there for a matter of days and might be expected to remain still longer. It was no overnight affair. There were the tents of the white men and the byût of Arabs neatly arranged with almost military precision and behind these the shelters of the negroes, lightly constructed of such materials as Nature had provided upon the spot.

Within the open front of an Arab beyt sat several white bournoosed Beduins drinking their inevitable coffee; in the shade of a great tree before another tent four white men were engrossed in a game of cards; among the native shelters a group of stalwart Galla warriors were playing at minkala. There were blacks of other tribes too—men of East Africa and of Central Africa, with a sprinkling of West Coast negroes.

It might have puzzled an experienced African traveller or hunter to catalog this motley aggregation of races and colors. There were far too many blacks to justify a belief that all were porters, for with all the impedimenta of the camp ready for transportation there would have been but a small fraction of a load for each of them, even after more than enough had been included among the askari, who do not carry any loads beside their rifles and ammunition.

Then, too, there were more rifles than would have been needed to protect even a larger party. There seemed, indeed, to be a rifle for every man. But these were minor details which made no impression upon Nkima. All that impressed him was the fact that here were many strange Tarmangani and Gomangani in the country of his master; and as all strangers were, to Nkima, enemies, he was perturbed. Now, more than ever he wished that he might find Tarzan.

A swarthy, turbaned East Indian sat cross-legged upon the ground before a tent, apparently sunk in meditation; but could one have seen his dark, sensuous eyes, he would have discovered that their gaze was far from introspective—they were bent constantly upon another tent that stood a little apart from its fellows—and when a girl emerged from this tent, Raghunath Jafar arose and approached her. He smiled an oily smile as he spoke to her, but the girl did not smile as she replied. She spoke civilly, but she did not pause, continuing her way toward the four men at cards.

As she approached their table they looked up; and upon the face of each was reflected some pleasurable emotion, but whether it was the same in each, the masks that we call faces, and which are trained to conceal our true thoughts, did not divulge. Evident it was, however, that the girl was popular.

"Hello, Zora!" cried a large, smooth-faced fellow. "Have a good nap?"

"Yes, Comrade," replied the girl; "but I am tired of napping. This inactivity is getting on my nerves."

"Mine, too," agreed the man.

"How much longer will you wait for the American, Comrade Zveri?" asked Raghunath Jafar.

The big man shrugged. "I need him," he replied. "We might easily carry on without him, but for the moral effect upon the world of having a rich and high-born American identified actively with the affair it is worth waiting."

"Are you quite sure of this gringo, Zveri?" asked a swarthy young Mexican sitting next to the big, smooth-faced man, who was evidently the leader of the expedition.

"I met him in New York and again in San Francisco," replied Zveri. "He has been very carefully checked and favorably recommended."

"I am always suspicious of these fellows who owe everything they have to capitalism," declared Romero. "It is in their blood—at heart they hate the proletariat, just as we hate them."

"This fellow is different, Miguel," insisted Zveri. "He has been won over so completely that he would betray his own father for the good of the cause—and already he is betraying his country."

A slight, involuntary sneer, that passed unnoticed by the others, curled the lip of Zora Drinov as she heard this description of the remaining member of the party, who had not yet reached the rendezvous.

Miguel Romero, the Mexican, was still unconvinced. "I have no use for gringos of any sort," he said.

Zveri shrugged his heavy shoulders. "Our personal animosities are of no importance," he said, "as against the interests of the workers of the world. When Colt arrives we must accept him as one of us; nor must we forget that however much we may detest America and Americans nothing of any moment may be accomplished in the world of today without them and their filthy wealth."

"Wealth ground out of the blood and sweat of the working class," growled Romero.

"Exactly," agreed Raghunath Jafar, "but how appropriate that this same wealth should be used to undermine and overthrow capitalistic America and bring the workers eventually into their own."

"That is precisely the way I feel about it," said Zveri. "I would rather use American gold in furthering the cause than any other—and after that British."

"But what do the puny resources of this single American mean to us?" demanded Zora. "A mere nothing compared to what America is already pouring into Soviet Russia. What is his treason compared with the treason of those others who are already doing more to hasten the day of world communism than the Third Internationale itself—it is nothing, not a drop in the bucket."

"What do you mean, Zora?" asked Miguel.

"I mean the bankers, and manufacturers, and engineers of America, who are selling their own country and the world to us in the hope of adding more gold to their already bursting coffers. One of their most pious and lauded citizens is building great factories for us in Russia, where we may turn out tractors and tanks; their manufacturers are vying with one another to furnish us with engines for countless thousands of airplanes; their engineers are selling us their brains and their skill to build a great modern manufacturing city, in which ammunitions and engines of war may be produced. These are the traitors, these are the men who are hastening the day when Moscow shall dictate the policies of a world."

"You speak as though you regretted it," said a dry voice at her shoulder.

The girl turned quickly. "Oh, it is you, Sheik Abu Batn?" she said, as she recognized the swart Arab who had strolled over from his coffee. "Our own good fortune does not blind me to the perfidiousness of the enemy, nor cause me to admire treason in anyone, even though I profit by it."

"Does that include me?" demanded Romero, suspiciously.

Zora laughed. "You know better than that, Miguel," she said. "You are of the working class—you are loyal to the workers of your own country—but these others are of the capitalistic class; their government is a capitalistic government that is so opposed to our beliefs that it has never recognized our government; yet, in their greed, these swine are selling out their own kind and their own country for a few more rotten dollars. I loathe them."

Zveri laughed. "You are a good Red, Zora," he cried; "you hate the enemy as much when he helps us as when he hinders."

"But hating and talking accomplish so little," said the girl. "I wish we might do something. Sitting here in idleness seems so futile."

"And what would you have us do?" demanded Zveri, good naturedly.

"We might at least make a try for the gold of Opar," she said. "If Kitembo is right, there should be enough there to finance a dozen expeditions such as you are planning, and we do not need this American—what do they call them, cake eaters?—to assist us in that venture."

"I have been thinking along similar lines," said Raghunath Jafar.

Zveri scowled. "Perhaps some of the rest of you would like to run this expedition," he said, crustily. "I know what I am doing and I don't have to discuss all my plans with anyone. When I have orders to give, I'll give them. Kitembo has already received his, and preparations have been under way for several days for the expedition to Opar."

"The rest of us are as much interested and are risking as much as you, Zveri," snapped Romero. "We were to work together—not as master and slaves."

"You'll soon learn that I am master," snarled Zveri in an ugly tone.

"Yes," sneered Romero, "the czar was master, too, and Obregon. You know what happened to them?"

Zveri leaped to his feet and whipped out a revolver, but as he levelled it at Romero the girl struck his arm up and stepped between them. "Are you mad, Zveri?" she cried.

"Do not interfere, Zora; this is my affair and it might as well be settled now as later. I am chief here and I am not going to have any traitors in my camp. Stand aside."

"No!" said the girl with finality. "Miguel was wrong and so were you, but to shed blood—our own blood—now would utterly ruin any chance we have of success. It would sow the seed of fear and suspicion and cost us the respect of the blacks, for they would know that there was dissension among us. Furthermore, Miguel is not armed; to shoot him would be cowardly murder that would lose you the respect of every decent man in the expedition." She had spoken rapidly in Russian, a language that was understood by only Zveri and herself, of those who were present; then she turned again to Miguel and addressed him in English. "You were wrong, Miguel," she said gently. "There must be one responsible head, and Comrade Zveri was chosen for the responsibility. He regrets that he acted hastily. Tell him that you are sorry for what you said, and then the two of you shake hands and let us all forget the matter."

For an instant Romero hesitated; then he extended his hand toward Zveri. "I am sorry," he said.

The Russian took the proffered hand in his and bowed stiffly. "Let us forget it, Comrade," he said; but the scowl was still upon his face, though no darker than that which clouded the Mexican's.

Little Nkima yawned and swung by his tail from a branch far overhead. His curiosity concerning these enemies was sated. They no longer afforded him entertainment, but he knew that his master should know about their presence; and that thought, entering his little head, recalled his sorrow and his great yearning for Tarzan, to the end that he was again imbued with a grim determination to continue his search for the ape-man. Perhaps in half an hour some trivial occurrence might again distract his attention, but for the moment it was his life work. Swinging through the forest, little Nkima held the fate of Europe in his pink palm, but he did not know it.

The afternoon was waning. In the distance a lion roared. An instinctive shiver ran up Nkima's spine. In reality, however, he was not much afraid, knowing, as he did, that no lion could reach him in the tree tops.

A young man marching near the head of a safari cocked his head and listened. "Not so very far away, Tony," he said.

"No, sir; much too close," replied the Filipino.

"You'll have to learn to cut out that 'sir' stuff, Tony, before we join the others," admonished the young man.

The Filipino grinned. "All right, Comrade," he assented. "I got so used to calling everybody 'sir' it hard for me to change."

"I'm afraid you're not a very good Red then, Tony."

"Oh, yes I am," insisted the Filipino emphatically. "Why else am I here? You think I like come this God forsaken country full of lion, ant, snake, fly, mosquito just for the walk? No, I come lay down my life for Philippine independence."

"That's noble of you all right, Tony," said the other gravely; "but just how is it going to make the Philippines free?"

Antonio Mori scratched his head. "I don't know," he admitted; "but it make trouble for America."

A half hour later the lion roared again, and so disconcertingly close and unexpected rose the voice of thunder from the jungle beneath him that little Nkima nearly fell out of the tree through which he was passing. With a scream of terror he scampered as high aloft as he could go and there he sat, scolding angrily.

The lion, a magnificent full-maned male, stepped into the open beneath the tree in which the trembling Nkima clung. Once again he raised his mighty voice until the ground itself trembled to the great, rolling volume of his challenge. Nkima looked down upon him and suddenly ceased to scold. Instead he leaped about excitedly, chattering and grimacing. Numa, the lion, looked up; and then a strange thing occurred. The monkey ceased its chattering and voiced a low, peculiar sound. The eyes of the lion, that had been glaring balefully upward, took on a new and almost gentle expression. He arched his back and rubbed his side luxuriously against the bole of the tree, and from those savage jaws came a soft, purring sound. Then little Nkima dropped quickly downward through the foliage of the tree, gave a final nimble leap, and alighted upon the thick mane of the king of beasts.

II

THE HINDU

With the coming of a new day came a new activity to the camp of the conspirators. Now were the Bedaùwy drinking no coffee in the múk'aad; the cards of the whites were put away and the Galla warriors played no longer at minkala.

Zveri sat behind his folding camp table directing his aides and with the assistance of Zora and Raghunath Jafar issued ammunition to the file of armed men marching past them. Miguel Romero and the two remaining whites were supervising the distribution of loads among the porters. Savage black Kitembo moved constantly among his men, hastening laggards from belated breakfast fires and forming those who had received their ammunition into companies. Abu Batn, the sheykh, squatted aloof with his sun-bitten warriors. They, always ready, watched with contempt the disorderly preparations of their companions.

"How many are you leaving to guard the camp?" asked Zora.

"You and Comrade Jafar will remain in charge here," replied Zveri. "Your boys and ten askaris also will remain as camp guard."

"That will be plenty," replied the girl. "There is no danger."

"No," agreed Zveri, "not now, but if that Tarzan were here it would be different. I took pains to assure myself as to that before I chose this region for our base camp, and I have learned that he has been absent for a great while—went on some fool dirigible expedition that has never been heard from. It is almost certain that he is dead."

When the last of the blacks had received his issue of ammunition, Kitembo assembled his tribesmen at a little distance from the rest of the expedition and harangued them in a low voice. They were Basembos, and Kitembo, their chief, spoke to them in the dialect of their people.

Kitembo hated all whites. The British had occupied the land that had been the home of his people since before the memory of man; and because Kitembo, hereditary chief, had been irreconcilable to the domination of the invaders they had deposed him, elevating a puppet to the chieftaincy.

To Kitembo, the chief—savage, cruel and treacherous—all whites were anathema, but he saw in his connection with Zveri an opportunity to be avenged upon the British; and so he had gathered about him many of his tribesmen and enlisted in the expedition that Zveri promised him would rid the land forever of the British and restore Kitembo to even greater power and glory than had formerly been the lot of Basembo chiefs.

It was not, however, always easy for Kitembo to hold the interest of his people in this undertaking. The British had greatly undermined his power and influence, so that warriors, who formerly might have been as subservient to his will as slaves, now dared openly to question his authority. There had been no demur so long as the expedition entailed no greater hardships than short marches, pleasant camps, and plenty of food, with West Coast blacks, and members of other tribes less warlike than the Basembos, to act as porters, carry the loads, and do all of the heavy work; but now, with fighting looming ahead, some of his people had desired to know just what they were going to get out of it, having, apparently, little stomach for risking their hides for the gratification of the ambitions or hatreds of either the white Zveri or the black Kitembo.

It was for the purpose of mollifying these malcontents that Kitembo was now haranguing his warriors, promising them loot on the one hand and ruthless punishment on the other as a choice between obedience and mutiny. Some of the rewards he dangled before their imaginations might have caused Zveri and the other white members of the expedition considerable perturbation could they have understood the Basembo dialect; but perhaps a greater argument for obedience to his commands was the genuine fear that most of his followers still entertained for their pitiless chieftain.

Among the other blacks of the expedition were outlaw members of several tribes and a considerable number of porters hired in the ordinary manner to accompany what was officially described as a scientific expedition.

Abu Batn and his warriors were animated to temporary loyalty to Zveri by two motives—a lust for loot and hatred for all Nasrâny as represented by the British influence in Egypt and out in to the desert, which they considered their hereditary domain.

The members of other races accompanying Zveri were assumed to be motivated by noble, humanitarian aspirations; but it was, nevertheless, true that their leader spoke to them more often of the acquisition of personal riches and power than of the advancement of the brotherhood of man or the rights of the proletariat.

It was, then, such a loosely knit, but none the less formidable expedition, that set forth this lovely morning upon the sack of the treasure vaults of mysterious Opar.

As Zora Drinov watched them depart, her beautiful, inscrutable eyes remained fixed steadfastly upon the person of Peter Zveri until he had disappeared from view along the river trail that led into the dark forest.

Was it a maid watching in trepidation the departure of her lover upon a mission fraught with danger, or—

"Perhaps he will not return," said an oily voice at her shoulder.

The girl turned her head to look into the half-closed eyes of Raghunath Jafar. "He will return, Comrade," she said. "Peter Zveri always returns to me."

"You are very sure of him," said the man, with a leer.

"It is written," replied the girl as she started to move toward her tent.

"Wait," said Jafar.

She stopped and turned toward him. "What do you want?" she asked.

"You," he replied. "What do you see in that uncouth swine, Zora? What does he know of love or beauty? I can appreciate you, beautiful flower of the morning. With me you may attain the transcendent bliss of perfect love, for I am an adept in the cult of love. A beast like Zveri would only degrade you."

The sickening disgust that the girl felt she hid from the eyes of the man, for she realized that the expedition might be gone for days and that during that time she and Jafar would be practically alone together, except for a handful of savage black warriors whose attitude toward a matter of this nature between an alien woman and an alien man she could not anticipate; but she was none the less determined to put a definite end to his advances.

"You are playing with death, Jafar," she said quietly. "I am here upon no mission of love, and if Zveri should learn of what you have said to me he would kill you. Do not speak to me again on this subject."

"It will not be necessary," replied the Hindu, enigmatically. His half-closed eyes were fixed steadily upon those of the girl. For perhaps less than half a minute the two stood thus, while there crept through Zora Drinov a sense of growing weakness, a realization of approaching capitulation. She fought against it, pitting her will against that of the man. Suddenly she tore her eyes from his. She had won, but victory left her weak and trembling as might be one who had but just experienced a stubbornly contested physical encounter. Turning quickly away, she moved swiftly toward her tent, not daring to look back for fear that she might again encounter those twin pools of vicious and malignant power that were the eyes of Raghunath Jafar; and so she did not see the oily smile of satisfaction that twisted the sensuous lips of the Hindu, nor did she hear his whispered repetition—"It will not be necessary."

As the expedition wound along the trail that leads to the foot of the barrier cliffs that hem the lower frontier of the arid plateau beyond which stand the ancient ruins that are Opar, Wayne Colt, far to the west, pushed on toward the base camp of the conspirators. To the south, a little monkey rode upon the back of a great lion, shrilling insults now with perfect impunity at every jungle creature that crossed their path; while, with equal contempt for all lesser creatures, the mighty carnivore strode haughtily down wind, secure in the knowledge of his unquestioned might. A herd of antelope, grazing in his path, caught the acrid scent of the cat and moved nervously about; but when he came within sight of them they trotted only a short distance to one side, making a path for him; and, while he was still in sight, they resumed their feeding, for Numa, the lion had fed well and the herbivores knew, as creatures of the wild know many things that are beyond the dull sensibilities of man, and felt no fear of Numa with a full belly.

To others, yet far off, came the scent of the lion; and they, too, moved nervously, though their fear was less than had been the first fear of the antelopes. These others were the great apes of the tribe of To-yat, whose mighty bulls had little cause to fear even Numa himself, though their shes and their balus might well tremble.

As the cat approached, the Mangani became more restless and more irritable. To-yat, the king ape, beat his breast and bared his great fighting fangs. Ga-yat, his powerful shoulders hunched, moved to the edge of the herd nearest the approaching danger. Zu-tho thumped a warning menace with his calloused feet. The shes called their balus to them, and many took to the lower branches of the larger trees or sought positions close to an arboreal avenue of escape.

It was at this moment that an almost naked white man dropped from the dense foliage of a tree and alighted in their midst. Taut nerves and short tempers snapped. Roaring and snarling, the herd rushed upon the rash and hated man-thing. The king ape was in the lead.

"To-yat has a short memory," said the man in the tongue of the Mangani.

For an instant the ape paused, surprised perhaps to hear the language of his kind issuing from the lips of a man-thing. "I am To-yat!" he growled. "I kill."

"I am Tarzan," replied the man, "mighty hunter, mighty fighter. I come in peace."

"Kill! Kill!" roared To-yat, and the other great bulls advanced, bare-fanged, menacingly.

"Zu-tho! Ga-yat!" snapped the man, "it is I, Tarzan of the Apes;" but the bulls were nervous and frightened now, for the scent of Numa was strong in their nostrils, and the shock of Tarzan's sudden appearance had plunged them into a panic.

"Kill! Kill!" they bellowed, though as yet they did not charge, but advanced slowly, working themselves into the necessary frenzy of rage that would terminate in a sudden, blood-mad rush that no living creature might withstand and which would leave naught but torn and bloody fragments of the object of their wrath.

And then a shrill scream broke from the lips of a great, hairy mother with a tiny balu on her back. "Numa!" she shrieked, and, turning, fled into the safety of the foliage of a nearby tree.

Instantly the shes and balus remaining upon the ground took to the trees. The bulls turned their attention for a moment from the man to the new menace. What they saw upset what little equanimity remained to them. Advancing straight toward them, his round, yellow-green eyes blazing in ferocity, was a mighty, yellow lion; and upon his back perched a little monkey, screaming insults at them. The sight was too much for the apes of To-yat, and the king was the first to break before it. With a roar, the ferocity of which may have salved his self esteem, he leaped for the nearest tree; and instantly the others broke and fled, leaving the white giant to face the angry lion alone.

With blazing eyes the king of beasts advanced upon the man, his head lowered and flattened, his tail extended, the brush flicking. The man spoke a single word in a low tone that might have carried but a few yards. Instantly the head of the lion came up, the horrid glare died in his eyes; and at the same instant the little monkey, voicing a shrill scream of recognition and delight, leaped over Numa's head and in three prodigious bounds was upon the shoulder of the man, his little arms encircling the bronzed neck.

"Little Nkima!" whispered Tarzan, the soft cheek of the monkey pressed against his own.

The lion strode majestically forward. He sniffed the bare legs of the man, rubbed his head against his side and lay down at his feet.

"Jad-bal-ja!" greeted the ape-man.

The great apes of the tribe of To-yat watched from the safety of the trees. Their panic and their anger had subsided. "It is Tarzan," said Zu-tho.

"Yes, it is Tarzan," echoed Ga-yat.

To-yat grumbled. He did not like Tarzan, but he feared him; and now, with this new evidence of the power of the great Tarmangani, he feared him even more.

For a time Tarzan listened to the glib chattering of little Nkima. He learned of the strange Tarmangani and the many Gomangani warriors who had invaded the domain of the Lord of the Jungle.

The great apes moved restlessly in the trees, wishing to descend; but they feared Numa, and the great bulls were too heavy to travel in safety upon the high-flung leafy trails along which the lesser apes might pass with safety, and so could not depart until Numa had gone.

"Go away!" cried To-yat, the King. "Go away, and leave the Mangani in peace."

"We are going," replied the ape-man, "but you need not fear either Tarzan or the Golden Lion. We are your friends. I have told Jad-bal-ja that he is never to harm you. You may descend."

"We shall stay in the trees until he has gone," said To-yat; "he might forget."

"You are afraid," said Tarzan contemptuously. "Zu-tho or Ga-yat would not be afraid."

"Zu-tho is afraid of nothing," boasted that great bull.

Without a word Ga-yat climbed ponderously from the tree in which he had taken refuge and, if not with marked enthusiasm, at least with slight hesitation, advanced toward Tarzan and Jad-bal-ja, the Golden Lion. His fellows eyed him intently, momentarily expecting to see him charged and mauled by the yellow-eyed destroyer that lay at Tarzan's feet watching every move of the shaggy bull. The Lord of the Jungle also watched great Numa, for none knew better than he, that a lion, however accustomed to obey his master, is still a lion. The years of their companionship, since Jad-bal-ja had been a little, spotted, fluffy ball, had never given him reason to doubt the loyalty of the carnivore, though there had been times when he had found it both difficult and dangerous to thwart some of the beast's more ferocious hereditary instincts.

Ga-yat approached, while little Nkima scolded and chattered from the safety of his master's shoulder; and the lion, blinking lazily, finally looked away. The danger, if there had been any, was over—it is the fixed, intent gaze of the lion that bodes ill.

Tarzan advanced and laid a friendly hand upon the shoulder of the ape. "This is Ga-yat," he said addressing Jad-bal-ja, "friend of Tarzan; do not harm him." He did not speak in any language of man. Perhaps the medium of communication that he used might not properly be called a language at all, but the lion and the great ape and the little Manu understood him.

"Tell the Mangani that Tarzan is the friend of little Nkima," shrilled the monkey. "He must not harm little Nkima."

"It is as Nkima has said," the ape-man assured Ga-yat.

"The friends of Tarzan are the friends of Ga-yat," replied the great ape.

"It is well," said Tarzan, "and now I go. Tell To-yat and the others what we have said and tell them also that there are strange men in this country which is Tarzan's. Let them watch them, but do not let the men see them, for these are bad men, perhaps, who carry the thunder sticks that hurl death with smoke and fire and a great noise. Tarzan goes now to see why these men are in his country."

Zora Drinov had avoided Jafar since the departure of the expedition to Opar. Scarcely had she left her tent, feigning a headache as an excuse, nor had the Hindu made any attempt to invade her privacy. Thus passed the first day. Upon the morning of the second Jafar summoned the head man of the askaris that had been left to guard them and to procure meat.

"Today," said Raghunath Jafar, "would be a good day to hunt. The signs are propitious. Go, therefore, into the forest, taking all your men, and do not return until the sun is low in the west. If you do this there will be presents for you, besides all the meat you can eat from the carcasses of your kills. Do you understand?"

"Yes, Bwana," replied the black.

"Take with you the boy of the woman. He will not be needed here. My boy will remain to cook for us."

"Perhaps he will not come," suggested the negro.

"You are many, he is only one; but do not let the woman know that you are taking him."

"What are the presents?" demanded the head man.

"A piece of cloth and cartridges," replied Jafar.

"And the curved sword that you carry when we are on the march."

"No," said Jafar.

"This is not a good day to hunt," replied the black, turning away.

"Two pieces of cloth and fifty cartridges," suggested Jafar.

"And the curved sword," and thus, after much haggling, the bargain was made.

The head man gathered his askaris and bade them prepare for the hunt, saying that the brown bwana had so ordered, but he said nothing about any presents. When they were ready, he dispatched one to summon the white woman's servant.

"You are to accompany us on the hunt," he said to the boy.

"Who said so?" demanded Wamala.

"The brown bwana," replied Kahiya, the head man.

Wamala laughed. "I take my orders from my mistress—not from the brown bwana."

Kahiya leaped upon him and clapped a rough palm across his mouth as two of his men seized Wamala upon either side. "You take your orders from Kahiya," he said. Hunting spears were pressed against the boy's trembling body. "Will you go upon the hunt with us?" demanded Kahiya.

"I go," replied Wamala. "I did but joke."

As Zveri led his expedition toward Opar, Wayne Colt, impatient to join the main body of the conspirators, urged his men to greater speed in their search for the camp. The principal conspirators had entered Africa at different points that they might not arouse too much attention by their numbers. Pursuant to this plan Colt had landed on the west coast and had travelled inland a short distance by train to railhead, from which point he had had a long and arduous journey on foot; so that now, with his destination almost in sight, he was anxious to put a period to this part of his adventure. Then, too, he was curious to meet the other principals in this hazardous undertaking, Peter Zveri being the only one with whom he was acquainted.

The young American was not unmindful of the great risks he was inviting in affiliating himself with an expedition which aimed at the peace of Europe and at the ultimate control of a large section of Northeastern Africa through the disaffection by propaganda of large and warlike native tribes, especially in view of the fact that much of their operation must be carried on within British territory, where British power was considerably more than a mere gesture. But, being young and enthusiastic, however misguided, these contingencies did not weigh heavily upon his spirits, which, far from being depressed, were upon the contrary eager and restless for action.

The tedium of the journey from the coast had been unrelieved by pleasurable or adequate companionship, since the childish mentality of Tony could not rise above a muddy conception of Philippine independence and a consideration of the fine clothes he was going to buy when, by some vaguely visualized economic process, he was to obtain his share of the Ford and Rockefeller fortunes.

However, notwithstanding Tony's mental shortcomings, Colt was genuinely fond of the youth and as between the companionship of the Filipino or Zveri, he would have chosen the former, his brief acquaintance with the Russian in New York and San Francisco having convinced him that as a play-fellow he left everything to be desired; nor had he any reason to anticipate that he would find any more congenial associates among the conspirators.

Plodding doggedly onward, Colt was only vaguely aware of the now familiar sights and sounds of the jungle, both of which by this time, it must be admitted, had considerably palled upon him. Even had he taken particular note of the latter, it is to be doubted that his untrained ear would have caught the persistent chatter of a little monkey that followed in the trees behind him; nor would this have particularly impressed him, unless he had been able to know that this particular little monkey rode upon the shoulder of a bronzed Apollo of the forest, who moved silently in his wake along a leafy highway of the lower terraces.

Tarzan had guessed that perhaps this white man, upon whose trail he had come unexpectedly, was making his way toward the main camp of the party of strangers for which the Lord of the Jungle was searching; and so, with the persistence and patience of the savage stalker of the jungle, he followed Wayne Colt; while little Nkima, riding upon his shoulder, berated his master for not immediately destroying the Tarmangani and all his party, for little Nkima was a bloodthirsty soul when the spilling of blood was to be accomplished by someone else.

And while Colt impatiently urged his men to greater speed and Tarzan followed and Nkima scolded, Raghunath Jafar approached the tent of Zora Drinov. As his figure darkened the entrance, casting a shadow across the book she was reading, the girl looked up from the cot upon which she was lying.

The Hindu smiled his oily, ingratiating smile. "I came to see if your headache was better," he said.

"Thank you, no," said the girl coldly; "but perhaps with undisturbed rest I may be better soon."

Ignoring the suggestion, Jafar entered the tent and seated himself in a camp chair. "I find it lonely," he said, "since the others have gone. Do you not also?"

"No," replied Zora. "I am quite content to be alone and resting."

"Your headache developed very suddenly," said Jafar. "A short time ago you seemed quite well and animated."

The girl made no reply. She was wondering what had become of her boy, Wamala, and why he had disregarded her explicit instructions to permit no one to disturb her. Perhaps Raghunath Jafar read her thoughts, for to East Indians are often attributed uncanny powers, however little warranted such a belief may be. However that may be, his next words suggested the possibility.

"Wamala has gone hunting with the askaris," he said.

"I gave him no such permission," said Zora.

"I took the liberty of doing so," said Jafar.

"You had no right," said the girl angrily, sitting up upon the edge of her cot. "You have presumed altogether too far, Comrade Jafar."

"Wait a moment, my dear," said the Hindu soothingly. "Let us not quarrel. As you know, I love you and love does not find confirmation in crowds. Perhaps I have presumed, but it was only for the purpose of giving me an opportunity to plead my cause without interruption; and then, too, as you know, all is fair in love and war."

"Then we may consider this as war," said the girl, "for it certainly is not love, either upon your side or upon mine. There is another word to describe what animates you, Comrade Jafar, and that which animates me now is loathing. I could not abide you if you were the last man on earth, and when Zveri returns, I promise you that there shall be an accounting."

"Long before Zveri returns I shall have taught you to love me," said the Hindu, passionately. He arose and came toward her. The girl leaped to her feet, looking about quickly for a weapon of defense. Her cartridge belt and revolver hung over the chair in which Jafar had been sitting, and her rifle was upon the opposite side of the tent.

"You are quite unarmed," said the Hindu; "I took particular note of that when I entered the tent. Nor will it do you any good to call for help; for there is no one in camp but you, and me, and my boy and he knows that, if he values his life, he is not to come here unless I call him."

"You are a beast," said the girl.

"Why not be reasonable, Zora?" demanded Jafar. "It would not harm you any to be kind to me, and it will make it very much easier for you. Zveri need know nothing of it, and once we are back in civilization again, if you still feel that you do not wish to remain with me I shall not try to hold you; but I am sure that I can teach you to love me and that we shall be very happy together."

"Get out!" ordered the girl. There was neither fear nor hysteria in her voice. It was very calm and level and controlled. To a man not entirely blinded by passion, that might have meant something—it might have meant a grim determination to carry self-defense to the very length of death—but Raghunath Jafar saw only the woman of his desire, and stepping quickly forward he seized her.

Zora Drinov was young and lithe and strong, yet she was no match for the burly Hindu, whose layers of greasy fat belied the great physical strength beneath them. She tried to wrench herself free and escape from the tent, but he held her and dragged her back. Then she turned upon him in a fury and struck him repeatedly in the face, but he only enveloped her more closely in his embrace and bore her backward upon the cot.

III

OUT OF THE GRAVE

Wayne Colt's guide, who had been slightly in advance of the American, stopped suddenly and looked back with a broad smile. Then he pointed ahead. "The camp, Bwana!" he exclaimed triumphantly.

"Thank the Lord!" exclaimed Colt with a sigh of relief.

"It is deserted," said the guide.

"It does look that way, doesn't it?" agreed Colt. "Let's have a look around," and, followed by his men, he moved in among the tents. His tired porters threw down their loads and, with the askaris, sprawled at full length beneath the shade of the trees, while Colt, followed by Tony, commenced an investigation of the camp.

Almost immediately the young American's attention was attracted by the violent shaking of one of the tents. "There is someone or something in there," he said to Tony, as he walked briskly toward the entrance.

The sight within that met his eyes brought a sharp ejaculation to his lips—a man and woman struggling upon the ground, the former choking the bare throat of his victim while the girl struck feebly at his face with clenched fists.

So engrossed was Jafar in his unsuccessful attempt to subdue the girl that he was unaware of Colt's presence until a heavy hand fell upon his shoulder and he was jerked violently aside.

Consumed by maniacal fury, he leaped to his feet and struck at the American only to be met with a blow that sent him reeling backward. Again he charged and again he was struck heavily upon the face. This time he went to the ground, and as he staggered to his feet, Colt seized him, wheeled him around and hurtled him through the entrance of the tent, accelerating his departure with a well-timed kick. "If he tries to come back, Tony, shoot him," he snapped at the Filipino, and then turned to assist the girl to her feet. Half carrying her, he laid her on the cot and then, finding water in a bucket, bathed her forehead, her throat and her wrists.

Outside the tent Raghunath Jafar saw the porters and the askaris lying in the shade of a tree. He also saw Antonio Mori with a determined scowl upon his face and a revolver in his hand, and with an angry imprecation he turned and made his way toward his own tent, his face livid with anger and murder in his heart.

Presently Zora Drinov opened her eyes and looked up into the solicitous face of Wayne Colt, bending over her.

From the leafy seclusion of a tree above the camp, Tarzan of the Apes overlooked the scene below. A single, whispered syllable had silenced Nkima's scolding. Tarzan had noted the violent shaking of the tent that had attracted Colt's attention, and he had seen the precipitate ejection of the Hindu from its interior and the menacing attitude of the Filipino preventing Jafar's return to the conflict. These matters were of little interest to the ape-man. The quarrelings and defections of these people did not even arouse his curiosity. What he wished to learn was the reason for their presence here, and for the purpose of obtaining this information he had two plans. One was to keep them under constant surveillance until their acts divulged that which he wished to know. The other was to determine definitely the head of the expedition and then to enter the camp and demand the information he desired. But this he would not do until he had obtained sufficient information to give him an advantage. What was going on within the tent he did not know, nor did he care.

For several seconds after she opened her eyes Zora Drinov gazed intently into those of the man bent upon her. "You must be the American," she said finally.

"I am Wayne Colt," he replied, "and I take it from the fact that you guessed my identity that this is Comrade Zveri's camp."

She nodded. "You came just in time, Comrade Colt," she said.

"Thank God for that," he said.

"There is no God," she reminded him.

Colt flushed. "We are creatures of heredity and habit," he explained.

Zora Drinov smiled. "That is true," she said, "but it is our business to break a great many bad habits not only for ourselves, but for the entire world."

Since he had laid her upon the cot, Colt had been quietly appraising the girl. He had not known that there was a white woman in Zveri's camp, but had he it is certain that he would not have anticipated one at all like this girl. He would rather have visualized a female agitator capable of accompanying a band of men to the heart of Africa as a coarse and unkempt peasant woman of middle age; but this girl, from her head of glorious, wavy hair to her small well-shaped foot, suggested the antithesis of a peasant origin and, far from being unkempt, was as trig and smart as it were possible for a woman to be under such circumstances and, in addition, she was young and beautiful.

"Comrade Zveri is absent from camp?" he asked.

"Yes, he is away on a short expedition."

"And there is no one to introduce us to one another?" he asked, with a smile.

"Oh, pardon me," she said. "I am Zora Drinov."

"I had not anticipated such a pleasant surprise," said Colt. "I expected to find nothing but uninteresting men like myself. And who was the fellow I interrupted?"

"That was Raghunath Jafar, a Hindu."

"He is one of us?" asked Colt.

"Yes," replied the girl, "but not for long—not after Peter Zveri returns."

"You mean—?"

"I mean that Peter will kill him."

Colt shrugged. "It is what he deserves," he said. "Perhaps I should have done it."

"No," said the girl, "leave that for Peter."

"Were you left alone here in this camp without any protection?" demanded Colt.

"No. Peter left my boy and ten askaris, but in some way Jafar got them all out of camp."

"You will be safe now," he said. "I shall see to that until Comrade Zveri returns. I am going now to make my camp, and I shall send two of my askaris to stand guard before your tent."

"That is good of you," she said, "but I think now that you are here it will not be necessary."

"I shall do it anyway," he said. "I shall feel safer."

"And when you have made camp, will you come and have supper with me?" she asked, and then, "Oh, I forgot, Jafar has sent my boy away, too. There is no one to cook for me."

"Then, perhaps, you will dine with me," he said. "My boy is a fairly good cook."

"I shall be delighted, Comrade Colt," she replied.

As the American left the tent, Zora Drinov lay back upon the cot with half-closed eyes. How different the man had been from what she had expected. Recalling his features, and especially his eyes, she found it difficult to believe that such a man could be a traitor to his father or to his country, but then, she realized, many a man has turned against his own for a principle. With her own people it was different. They had never had a chance. They had always been ground beneath the heel of one tyrant or another. What they were doing they believed implicitly to be for their own and for their country's good. Among those of them who were motivated by honest conviction there could not fairly be brought any charge of treason, and yet, Russian though she was to the core, she could not help but look with contempt upon the citizens of other countries who turned against their governments to aid the ambitions of a foreign power. We may be willing to profit by the act of foreign mercenaries and traitors, but we cannot admire them.

As Colt crossed from Zora's tent to where his men lay to give the necessary instruction for the making of his camp, Raghunath Jafar watched him from the interior of his own tent. A malignant scowl clouded the countenance of the Hindu, and hatred smoldered in his eyes.

Tarzan, watching from above, saw the young American issuing instructions to his men. The personality of this young stranger had impressed Tarzan favorably. He liked him as well as he could like any stranger, for deeply ingrained in the fiber of the ape-man was the wild beast suspicion of all strangers and especially of all white strangers. As he watched him now nothing else within the range of his vision escaped him. It was thus that he saw Raghunath Jafar emerge from his tent, carrying a rifle. Only Tarzan and little Nkima saw this, and only Tarzan placed any sinister interpretation upon it.

Raghunath Jafar walked directly away from camp and entered the jungle. Swinging silently through the trees, Tarzan of the Apes followed him. Jafar made a half circle of the camp just within the concealing verdure of the jungle, and then he halted. From where he stood the entire camp was visible to him, but his own position was concealed by foliage.

Colt was watching the disposition of his loads and the pitching of his tent. His men were busy with the various duties assigned to them by their headman. They were tired and there was little talking. For the most part they worked in silence, and an unusual quiet pervaded the scene—a quiet that was suddenly and unexpectedly shattered by an anguished scream and the report of a rifle, blending so closely that it was impossible to say which had preceded the other. A bullet whizzed by Colt's head and nipped the lobe off the ear of one of his men standing behind him. Instantly the peaceful activities of the camp were supplanted by pandemonium. For a moment there was a difference of opinion as to the direction from which the shot and the scream had come, and then Colt saw a wisp of smoke rising from the jungle just beyond the edge of camp.

"There it is," he said, and started toward the point.

The headman of the askaris stopped him. "Do not go, Bwana," he said. "Perhaps it is an enemy. Let us fire into the jungle first."

"No," said Colt, "we will investigate first. Take some of your men in from the right, and I'll take the rest in from the left. We'll work around slowly through the jungle until we meet."

"Yes, Bwana," said the headman, and calling his men he gave the necessary instructions.

No sound of flight or any suggestion of a living presence greeted the two parties as they entered the jungle; nor had they discovered any signs of a marauder when, a few moments later, they made contact with one another. They were now formed in a half circle that bent back into the jungle and, at a word from Colt, they advanced toward the camp.

It was Colt who found Raghunath Jafar lying dead just at the edge of camp. His right hand grasped his rifle. Protruding from his heart was the shaft of a sturdy arrow.

The negroes gathering around the corpse looked at one another questioningly and then back into the jungle and up into the trees. One of them examined the arrow. "It is not like any arrow I have ever seen," he said. "It was not made by the hand of man."

Immediately the blacks were filled with superstitious fears. "The shot was meant for the bwana," said one; "therefore the demon who shot the arrow is a friend of our bwana. We need not be afraid."

This explanation satisfied the blacks, but it did not satisfy Wayne Colt. He was puzzling over it as he walked back into camp, after giving orders that the Hindu be buried.

Zora Drinov was standing in the entrance to her tent, and as she saw him she came to meet him. "What was it?" she asked. "What happened?"

"Comrade Zveri will not kill Raghunath Jafar," he said.

"Why?" she asked.

"Because Raghunath Jafar is already dead."

"Who could have shot the arrow?" she asked, after he had told her of the manner of the Hindu's death.

"I haven't the remotest idea," he admitted. "It is an absolute mystery, but it means that the camp is being watched and that we must be very careful not to go into the jungle alone. The men believe that the arrow was fired to save me from an assassin's bullet; and while it is entirely possible that Jafar may have been intending to kill me, I believe that if I had gone into the jungle alone instead of him it would have been I that would be lying out there dead now. Have you been bothered at all by natives since you made camp here, or have you had any unpleasant experiences with them at all?"

"We have not seen a native since we entered this camp. We have often commented upon the fact that the country seems to be entirely deserted and uninhabited, notwithstanding the fact that it is filled with game."

"This thing may help to account for the fact that it is uninhabited," suggested Colt, "or rather apparently uninhabited. We may have unintentionally invaded the country of some unusually ferocious tribe that takes this means of acquainting newcomers with the fact that they are persona non grata."

"You say one of our men was wounded?" asked Zora.

"Nothing serious. He just had his ear nicked a little."

"Was he near you?"

"He was standing right behind me," replied Colt.

"I think there is no doubt that Jafar meant to kill you," said Zora.

"Perhaps," said Colt, "but he did not succeed. He did not even kill my appetite; and if I can succeed in calming the excitement of my boy, we shall have supper presently."

From a distance Tarzan and Nkima watched the burial of Raghunath Jafar and a little later saw the return of Kahiya and his askaris with Zora's boy Wamala, who had been sent out of camp by Jafar.

"Where," said Tarzan to Nkima, "are all the many Tarmangani and Gomangani that you told me were in this camp?"

"They have taken their thundersticks and gone away," replied the little Manu. "They are hunting for Nkima."

Tarzan of the Apes smiled one of his rare smiles. "We shall have to hunt them down and find out what they are about, Nkima," he said.

"But it grows dark in the jungle soon," pleaded Nkima, "and then will Sabor, and Sheeta, and Numa, and Histah be abroad, and they, too, search for little Nkima."

Darkness had fallen before Colt's boy announced supper, and in the meantime Tarzan, changing his plans, had returned to the trees above the camp. He was convinced that there was something irregular in the aims of the expedition whose base he had discovered. He knew from the size of the camp that it had contained many men. Where they had gone and for what purpose were matters that he must ascertain. Feeling that this expedition, whatever its purpose, might naturally be a principal topic of conversation in the camp, he sought a point of vantage wherefrom he might overhear the conversations that passed between the two white members of the party beneath him; and so it was that as Zora Drinov and Wayne Colt seated themselves at the supper table, Tarzan of the Apes crouched amid the foliage of a great tree just above them.

"You have passed through a rather trying ordeal today," said Colt, "but you do not appear to be any the worse for it. I should think that your nerves would be shaken."

"I have passed through too much already in my life, Comrade Colt, to have any nerves left at all," replied the girl.

"I suppose so," said Colt. "You must have passed through the revolution in Russia."

"I was only a little girl at the time," she explained, "but I remember it quite distinctly."

Colt was gazing at her intently. "From your appearance," he ventured, "I imagine that you were not by birth of the proletariat."

"My father was a laborer. He died in exile under the Tzarist regime. That was how I learned to hate everything monarchistic and capitalistic. And when I was offered this opportunity to join Comrade Zveri, I saw another field in which to encompass my revenge, while at the same time advancing the interests of my class throughout the world."

"When I last saw Zveri in the United States," said Colt, "he evidently had not formulated the plans he is now carrying out, as he never mentioned any expedition of this sort. When I received orders to join him here, none of the details were imparted to me; and so I am rather in the dark as to what his purpose is."

"It is only for good soldiers to obey," the girl reminded him.

"Yes, I know that," agreed Colt, "but at the same time even a poor soldier may act more intelligently sometimes if he knows the objective."

"The general plan, of course, is no secret to any of us here," said Zora, "and I shall betray no confidence in explaining it to you. It is a part of a larger plan to embroil the capitalistic powers in wars and revolutions to such an extent that they will be helpless to unite against us.

"Our emissaries have been laboring for a long time toward the culmination of the revolution in India that will distract the attention and the armed forces of Great Britain. We are not succeeding so well in Mexico as we had planned, but there is still hope, while our prospects in the Philippines are very bright. The conditions in China you well know. She is absolutely helpless, and we have hope that with our assistance she will eventually constitute a real menace to Japan. Italy is a very dangerous enemy, and it is largely for the purpose of embroiling her in war with France that we are here."

"But just how can that be accomplished in Africa?" asked Colt.

"Comrade Zveri believes that it will be simple," said the girl. "The suspicion and jealousy that exist between France and Italy are well known; their race for naval supremacy amounts almost to a scandal. At the first overt act of either against the other, war might easily result, and a war between Italy and France would embroil all of Europe."

"But just how can Zveri, operating in the wilds of Africa, embroil Italy and France in war?" demanded the American.

"There is now in Rome a delegation of French and Italian Reds engaged in this very business. The poor men know only a part of the plan and, unfortunately for them, it will be necessary to martyr them in the cause for the advancement of our world plan. They have been furnished with papers outlining a plan for the invasion of Italian Somaliland by French troops. At the proper time one of Comrade Zveri's secret agents in Rome will reveal the plot to the Fascist Government; and almost simultaneously a considerable number of our own blacks, disguised in the uniforms of French native troops, led by the white men of our expedition, uniformed as French officers, will invade Italian Somaliland.

"In the meantime our agents are carrying on in Egypt and Abyssinia and among the native tribes of North Africa, and already we have definite assurance that with the attention of France and Italy distracted by war and Great Britain embarrassed by a revolution in India the natives of North Africa will arise in what will amount almost to a holy war for the purpose of throwing off the yoke of foreign domination and the establishment of autonomous soviet states throughout the entire area."

"A daring and stupendous undertaking," exclaimed Colt, "but one that will require enormous resources in money as well as men."

"It is Comrade Zveri's pet scheme," said the girl. "I do not know, of course, all the details of his organization and backing; but I do know that while he is already well financed for the initial operations, he is depending to a considerable extent upon this district for furnishing most of the necessary gold to carry on the tremendous operations that will be necessary to insure final success."

"Then I am afraid he is foredoomed to failure," said Colt, "for he surely cannot find enough wealth in this savage country to carry on any such stupendous program."

"Comrade Zveri believes to the contrary," said Zora; "in fact, the expedition that he is now engaged upon is for the purpose of obtaining the treasure he seeks."

Above them, in the darkness, the silent figure of the ape-man lay stretched at ease upon a great branch, his keen ears absorbing all that passed between them, while curled in sleep upon his bronzed back lay little Nkima, entirely oblivious of the fact that he might have listened to words well calculated to shake the foundations of organized government throughout the world.

"And where," demanded Colt, "if it is no secret, does Comrade Zveri expect to find such a great store of gold?"

"In the famous treasure vaults of Opar," replied the girl. "You certainly have heard of them."

"Yes," answered Colt, "but I never considered them other than purely legendary. The folklore of the entire world is filled with these mythical treasure vaults."

"But Opar is no myth," replied Zora.

If the startling information divulged to him affected Tarzan, it induced no outward manifestation. Listening in silence imperturbable, trained to the utmost refinement of self-control, he might have been part and parcel of the great branch upon which he lay, or of the shadowy foliage which hid him from view.

For a time Colt sat in silence, contemplating the stupendous possibilities of the plan that he had just heard unfolded. It seemed to him little short of the dream of a mad man, and he did not believe that it had the slightest chance for success. What he did realize was the jeopardy in which it placed the members of the expedition, for he believed that there would be no escape for any of them once Great Britain, France, and Italy were apprised of their activities; and, without conscious volition, his fears seemed centered upon the safety of the girl. He knew the type of people with whom he was working and so he knew that it would be dangerous to voice a doubt as to the practicability of the plan, for scarcely without exception the agitators whom he had met had fallen naturally into two separate categories, the impractical visionary, who believed everything that he wanted to believe, and the shrewd knave, actuated by motives of avarice, who hoped to profit either in power or riches by any change that he might be instrumental in bringing about in the established order of things. It seemed horrible that a young and beautiful girl should have been enticed into such a desperate situation. She seemed far too intelligent to be merely a brainless tool, and even his brief association with her made it most difficult for him to believe that she was a knave.

"The undertaking is certainly fraught with grave dangers," he said, "and as it is primarily a job for men I cannot understand why you were permitted to face the dangers and hardships that must of necessity be entailed by the carrying out of such a perilous campaign."

"The life of a woman is of no more value than that of a man," she declared, "and I was needed. There is always a great deal of important and confidential clerical work to be done which Comrade Zveri can entrust only to one in whom he has implicit confidence. He reposes such trust in me and, in addition, I am a trained typist and stenographer. Those reasons in themselves are sufficient to explain why I am here, but another very important one is that I desire to be with Comrade Zveri."

In the girl's words Colt saw the admission of a romance; but to his American mind this was all the greater reason why the girl should not have been brought along, for he could not conceive of a man exposing the girl he loved to such dangers.

Above them Tarzan of the Apes moved silently. First he reached over his shoulder and lifted little Nkima from his back. Nkima would have objected, but the veriest shadow of a whisper silenced him. The ape-man had various methods of dealing with enemies—methods that he had learned and practiced long before he had been cognizant of the fact that he was not an ape. Long before he had ever seen another white man he had terrorized the gomangani, the black men of the forest and the jungle, and had learned that a long step toward defeating an enemy may be taken by first demoralizing its morale. He knew now that these people were not only the invaders of his own domain and, therefore, his own personal enemies, but that they threatened the peace of Great Britain, which was dear to him, and of the rest of the civilized world, with which, at least, Tarzan had no quarrels. It is true that he held civilization in general in considerable contempt, but in even greater contempt he held those who interfered with the rights of others or with the established order of jungle or city.

As Tarzan left the tree in which he had been hiding, the two below him were no more aware of his departure than they had been of his presence. Colt found himself attempting to fathom the mystery of love. He knew Zveri, and it appeared inconceivable to him that a girl of Zora Drinov's type could be attracted by a man of Zveri's stamp. Of course, it was none of his affair, but it bothered him nevertheless because it seemed to constitute a reflection upon the girl and to lower her in his estimation. He was disappointed in her, and Colt did not like to be disappointed in people to whom he had been attracted.

"You knew Comrade Zveri in America, did you not?" asked Zora.

"Yes," replied Colt.

"What do you think of him?" she demanded.

"I found him a very forceful character," replied Colt. "I believe him to be a man who would carry on to a conclusion anything that he attempted. No better man could have been chosen for this mission."

If the girl had hoped to surprise Colt into an expression of personal regard or dislike for Zveri, she had failed, but if such was the fact she was too wise to pursue the subject further. She realized that she was dealing with a man from whom she would get little information that he did not wish her to have; but on the other hand a man who might easily wrest information from others, for he was that type which seemed to invite confidences, suggesting as he did, in his attitude, his speech and his manner a sterling uprightness of character that could not conceivably abuse a trust. She rather liked this upstanding young American, and the more she saw of him the more difficult she found it to believe that he had turned traitor to his family, his friends and his country. However, she knew that many honorable men had sacrificed everything to a conviction and, perhaps, he was one of these. She hoped that this was the explanation.

Their conversation drifted to various subjects—to their lives and experiences in their native lands—to the happenings that had befallen them since they had entered Africa, and, finally, to the experiences of the day. And while they talked, Tarzan of the Apes returned to the tree above them, but this time he did not come alone.

"I wonder if we shall ever know," she said, "who killed Jafar."

"It is a mystery that is not lessened by the fact that none of the askaris could recognize the type of arrow with which he was slain, though that, of course, might be accounted for by the fact that none of them are of this district."

"It has considerably shaken the nerves of the men," said Zora, "and I sincerely hope that nothing similar occurs again. I have found that it does not take much to upset these natives, and while most of them are brave in the face of known dangers, they are apt to be entirely demoralized by anything bordering on the supernatural."

"I think they felt better when they got the Hindu planted under ground," said Colt, "though some of them were not at all sure that he might not return anyway."

"There is not much chance of that," rejoined the girl, laughing.

She had scarcely ceased speaking when the branches above them rustled, and a heavy body plunged downward to the table top between them, crushing the flimsy piece of furniture to earth.

The two sprang to their feet, Colt whipping out his revolver and the girl stifling a cry as she stepped back. Colt felt the hairs rise upon his head and goose flesh form upon his arms and back, for there between them lay the dead body of Raghunath Jafar upon its back, the dead eyes rolled backward staring up into the night.

IV

INTO THE LION'S DEN

Nkima was angry. He had been awakened from the depth of a sound sleep, which was bad enough, but now his master had set out upon such foolish errands through the darkness of the night that, mingled with Nkima's scoldings were the whimperings of fear, for in every shadow he saw Sheeta, the panther, lurking and in each gnarled limb of the forest the likeness of Histah, the snake. While Tarzan had remained in the vicinity of the camp, Nkima had not been particularly perturbed, and when he had returned to the tree with his burden the little Manu was sure that he was going to remain there for the rest of the night; but instead he had departed immediately and now was swinging through the black forest with an evident fixity of purpose that boded ill for either rest or safety for little Nkima during the remainder of the night.

Whereas Zveri and his party had started slowly along winding jungle trails, Tarzan moved almost in an air line through the jungle toward his destination, which was the same as that of Zveri. The result was that before Zveri reached the almost perpendicular crag which formed the last and greatest natural barrier to the forbidden valley of Opar, Tarzan and Nkima had disappeared beyond the summit and were crossing the desolate valley, upon the far side of which loomed the great walls and lofty spires and turrets of ancient Opar. In the bright light of the African sun, domes and minarets shone red and gold above the city; and once again the ape-man experienced the same feeling that had impressed him upon the occasion, now years gone, when his eyes had first alighted upon the splendid panorama of mystery that had unfolded before them.

No evidence of ruin was apparent at this great distance. Once again, in imagination, he beheld a city of magnificent beauty, its streets and temples thronged with people; and once again his mind toyed with the mystery of the city's origin, when back somewhere in the dim vista of antiquity a race of rich and powerful people had conceived and built this enduring monument to a vanished civilization. It was possible to conceive that Opar might have existed when a glorious civilization flourished upon the great continent of Atlantis, which, sinking beneath the waves of the ocean, left this lost colony to death and decay.

That its few inhabitants were direct descendants of its once powerful builders seemed not unlikely in view of the rites and ceremonies of the ancient religion which they practiced, as well as by the fact that by scarcely any other hypothesis could the presence of a white-skinned people be accounted for in this remote and inaccessible African fastness.