Deerfoot on the Prairies

Edward S. Ellis

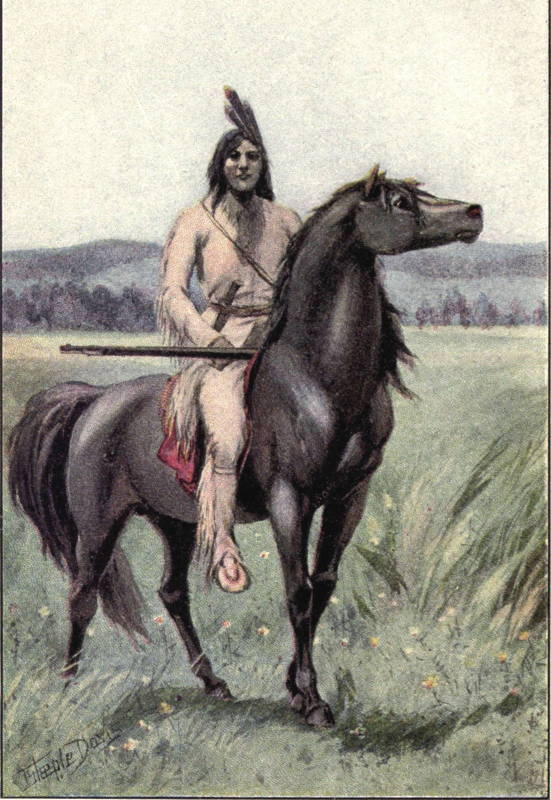

Deerfoot and Whirlwind.

Deerfoot on the

Prairies

Each contains seven half-tone engravings and color frontispiece. They make more real the fortunes and adventures of the heroic little band that journeys through the wilderness and prairies from the Ohio to the Pacific. It was in the time of daring when Lewis and Clark were engaged in their thrilling expedition that the adventures narrated by the distinguished author of boys’ books are described as occurring. Our old friends, George and Victor, of the “Log Cabin Series,” are again met with in these pages, and the opportunity of once more coming face to face with Deerfoot will be welcomed by every juvenile reader.

The New Deerfoot Series is bound in uniform style in cloth, with side and back stamped in colors.

| Price, single volume | $1.00 |

| Price, per set of three volumes, in attractive box | 3.00 |

CONTENTS

| Chap | |

| I. | Westward Bound |

| II. | The First Camp |

| III. | Thieves of the Night |

| IV. | An Acquaintance |

| V. | A Close Call |

| VI. | A Mishap |

| VII. | Jack Halloway |

| VIII. | Good Seed |

| IX. | A Battle Royal |

| X. | Whirlwind |

| XI. | Physician and Patient |

| XII. | A Hurried Flight |

| XIII. | A Startling Awakening |

| XIV. | Shoshone Callers |

| XV. | A Question of Skill and Courage |

| XVI. | Wireless Telegraphy |

| XVII. | In the Mountains |

| XVIII. | Indian Chivalry |

| XIX. | A Calamity |

| XX. | Old Friends |

| XXI. | Pressing Northward |

| XXII. | A Change of Plan |

| XXIII. | The Monarch of the Solitudes |

| XXIV. | A Memorable Encounter |

| XXV. | Through the Great Divide |

| XXVI. | Parting Company |

| XXVII. | Down the Columbia |

| XXVIII. | At Last |

ILLUSTRATIONS

CHAPTER I

WESTWARD BOUND.

ONE morning in early spring, at the beginning of the last century, a party of four persons left the frontier town of Woodvale, in southern Ohio, and started on their long journey across the continent.

Do you need an introduction to the little company? Hardly, and yet it is well to recall them to mind.

First of all was our old friend Deerfoot, the Shawanoe, to whom we bade good-bye at the close of the story “Deerfoot in the Forest,” with a hint of the important expedition upon which he had decided to enter with his companions. He was mounted on a tough, wiry pony that had been presented to him by his friend Simon Kenton, and which, in honor of the famous ranger, the new owner had named “Simon.”

This horse was provided with a bridle, but that was all. Deerfoot, one of the finest of horsemen, never used a saddle. He said the bare back of a well-conditioned steed was more pleasant than a seat of leather, and he had never yet bestrode an animal that could displace him. On this trip the Indian youth carried as his principal weapon the handsome rifle presented by General William H. Harrison, Governor of Indiana Territory. Deerfoot had not yielded a bit of his faith in his bow, but that implement would not prove so handy as the other in an excursion on horseback. Besides, his three companions had begged him to leave his bow at home, and he was quite willing to do so.

Deerfoot was dressed as he has been before described, but he carried a long, heavy blanket that was strapped to the back of his horse and served in lieu of a saddle. The powder horn and bullet pouch suspended from his neck were as full as they could carry. He looked so graceful on his animal that many expressions of admiration were heard from the people of Woodvale who had gathered to see the start. Deerfoot did not seem to hear any of the compliments, though some were addressed directly to him. He was never pleased with anything of that nature.

Little need be said of Mul-tal-la, the Blackfoot, who had come from the neighborhood of the Rocky Mountains on an exploring expedition of his own, and was now to return with the Shawanoe as his comrade. The sturdy, shaggy horse, which he had obtained through the help also of Simon Kenton, was accoutred like the one ridden by Deerfoot. The blanket strapped to his back was the one brought by the owner from that far-off region, and served him also as a saddle. The Blackfoot, like nearly all the Indians of the Northwest, was an excellent horseman. Through some whim, which no one understood, Mul-tal-la had named his animal “Bug,” a title so unromantic that for a long time it was never heard without causing a smile from his companions. Sometimes Mul-tal-la also grinned, but nothing could induce him to change the name.

You remember the grief of Victor Shelton was so depressing over the death of his father that he surely would have gone into a decline but for the ardor roused by this proposed excursion to the Pacific. The prospect was so fascinating that he came out of the dark clouds that gathered about him, and was the most enthusiastic of the four.

George was almost as deeply stirred and in as high spirits as his brother, but now and then a tremor of fear passed over him when he thought of what they would have to pass through before their return. He would have shrunk and probably turned back but for Deerfoot. There was no person in the world in whom he had such faith as in the young Shawanoe; but there is a limit to human attainment, and it might be that his dusky friend would soon reach his when the four turned their faces westward.

George had named his horse “Jack,” while Victor called his “Prince.” All were quite similar to one another, being strong, sturdy, docile and enduring, but none was specially gifted in the way of speed. More than likely they would meet many of their kind among the Indians which would be their superior in fleetness. But, if danger threatened, our friends would not rely upon their horses for safety.

Now, in setting out on so long a journey, which of necessity must last many months, our friends had to carry some luggage with them. This was made as light as possible, but pared to the utmost there was enough to require a fifth horse. While of the same breed as the others, he was of stronger build and best fitted for burdens. He was the gift of Ralph Genther, who, you may recall, was beaten in the turkey shoot by Deerfoot. It was Genther who named him “Zigzag.”

“’Cause,” explained the donor, “if you let him to go as he pleases, he’ll make the crookedest track in creation; he will beat a ram’s horn out of sight.”

Excepting his blanket, Mul-tal-la had no luggage which he did not wear on his person. It must be admitted that the American Indian as a rule is much lacking in that virtue which is said to be next to godliness. Despite the romance that is often thrown around the red man, it is generally more pleasant to view him at a distance. Close companionship with him is by no means pleasant.

I need hardly say that it was not so with Deerfoot. He was as dainty as any lady with his person. Kenton, Boone and others had laughed at him many times because of his care in bathing and the frequency with which he plunged into icy cold water for no other reason than for tidiness and health. The material of which his hunting shirt and leggings were made allowed them to be worn a long time without showing the effects, but underneath them was underclothing kept scrupulously clean by Deerfoot’s own hands. Only his close friends knew of his care in this respect, and some of them looked upon it as a weakness approaching effeminacy. And you and I esteem him all the more for these traits, which harmonized with the nobility of his character.

So it was that in the large package secured to the back of Zigzag was considerable that Deerfoot himself had wrapped up, and with the modesty of a girl carefully screened from prying eyes. Aunt Dinah, had she been permitted, would have loaded down two horses with articles for the twins, who, she declared, could not possibly get on without them. As it was, it is enough to say that the boys were far better remembered than they would have been if left to themselves. As Victor expressed it when he saw her gathering and tying up the goods, they had enough to last them for a journey round the world.

The start was made early on Monday morning, when the sun was shining bright and the opening spring stirred every heart into life and filled it with thankfulness to the Giver of All Good. Men, women and children had gathered in the clearing to the north of the settlement to see the party start and to wish them good speed on their journey. Deerfoot and Mul-tal-la had ridden in from the Shawanoe’s home the day before, so that the start might be made from the settlement.

There were the laughing, the jesting, the merry and earnest expressions, with here and there a moist eye, when the travelers were seen seated on their horses and pausing for the final words. The one most to be pitied in all the group was Aunt Dinah, who was bravely trying to hide her real feelings under an expansive smile, in which there was not a shadow of mirth or pleasantry. She stood on the outer edge of the boisterous group, her folded hands under her apron, her eyes fixed on the boys, who were laughing, shaking hands and exchanging wishes and jests with their friends.

Suddenly the colored woman walked forward, pushing her way through the throng to the side of Deerfoot. Then she drew a piece of old-fashioned blue writing paper from under her apron and handed it up to him. He looked smilingly down at her, and she, without saying anything, walked back to the fringe of people and faced around again.

Deerfoot opened the slip and saw some writing in pencil. During the years when George and Victor Shelton struggled, with more or less success, to obtain a common-school education, Aunt Dinah had managed to pick up a bit here and there of elementary knowledge. She had spent a long time the night before, groaning in spirit, often sharpening her stub of a pencil, which, of course, she frequently thrust into her mouth, rubbing out and re-writing, perspiring and toiling with might and main to put together a message for the young Shawanoe’s eyes alone. Not until the other members of the household had long been sunk in slumber did she get the missive in final shape.

Some of the letters were turned backward, all curiously twisted, the lines irregular and the writing grotesque, but the youth to whom the paper was passed made out the following:

“Mister Dearfut—i feal orful bad 2 hav u go orf with them preshus babiz—pleas tak gud car of em, and bring em back rite side up—

“i’ll pra 4 u and the babiz evry nite and mornin, and if i doan forgot in de midle ob de da. i’ll pra speshully 4 u, cause as long as ure all rite, they’ll B all rite.

“Ant Dine.

“p.s.—u’ll fine rapped in paper in de top bundel sum caik dat am 4 u speshully, but u may let de oders hab 1 bite if u feels like it—member dat i’m prayin 4 u.

“p.s.—Doan eet 2 mutch ob de caik 2 wunst, or it’ll maik yo syck—it’ll B jus’ like you 2 gib it awl to de oders, but doan you doot! Eet mose ob it yosellf.

“p.s.—De caik am 4 yo speshully. Ise prayin’ 4 yo.

“p.s.—Doan forgot Ise prayin’ 4 yo. De caik am 4 yo.

“p.s.—De caik am yo’s—Ise prayin’ 4 yo.”

There was not the ghost of a smile on the face of the Shawanoe while carefully tracing the meaning of this crude writing. He gently refolded the paper, reached one hand within his hunting shirt, and, drawing out his Bible, put the folded paper between the leaves and replaced the book. Then, heedless of the clamor around him, he looked over the heads of the people at the lonely woman standing a little way off and watching him with manifest embarrassment.

Turning the head of his horse toward her, he deftly directed him through the throng and halted at the side of Aunt Dinah. She was so confused that she was on the point of making off, for nearly everyone was looking at the two, the action of Deerfoot having drawn attention to the couple. Leaning over his horse he extended his palm.

“Good-bye, Aunt Dinah.”

She bashfully reached up her big hard hand. He held it for a few moments, and, looking down in the ebon countenance, spoke in a low voice:

“Deerfoot thanks you; he is glad that you will pray to the Great Spirit for him, for he needs your prayers. Your promise is sweet to Deerfoot.”

Aunt Dinah did not speak, for with every eye upon her and the Indian she could not think of a syllable to say. While she was trying to do so, Deerfoot did something which no one ever saw him do before, and which was so strange that it hushed every voice. He leaned still farther from the back of his horse and deliberately touched his lips to the cheek of the colored woman. Then he straightened up, and, without a word, started his animal on a brisk walk to the northward, the others falling into line behind him.

CHAPTER II

THE FIRST CAMP.

IT was inevitable that, during the weeks and months spent by Deerfoot and Mul-tal-la together, they talked often and long about the journey to the Northwest. At night in the depth of the forest, by the crackling camp-fire, or when lolling in the cavern home of the young Shawanoe, it was the one theme in which both, and especially the younger, was absorbingly interested.

You need hardly be reminded that a hundred years ago the immense territory west of the Mississippi was an unknown region. Teeming to-day with a bustling, progressive people numbering millions, covered with large cities and towns, grid-ironed by railways, honeycombed with mines, humming with industry, and the seat of future empire, it was at the opening of the nineteenth century a vast solitude, the home of the wild Indian and wild animal.

A few daring hunters and trappers had penetrated for a little way into the “Louisiana Purchase,” and they carried on a disjointed barter with the red men, but the fragmentary knowledge brought back by them scarcely pierced the shell of general ignorance. Captains Lewis and Clark had not yet made their famous journey across the continent, but they were getting ready to do so, for President Jefferson’s heart was wrapped up in developing the largest real estate transaction ever made.

It may be said that Deerfoot pumped the Blackfoot dry. Had that enterprising traveler kept a diary of his journeyings and experiences from the time he and his companion started eastward, it would not have told the Shawanoe more than he gained from his friend by his continuous questioning. Deerfoot traced with a pencil on a sheet of paper a rude map of the western country, based wholly on the information gained from his guest. He made many changes and corrections before he completed and filed it away, as may be said, for future use.

Several important facts were thus established, and these you must bear in mind in order to understand the incidents I have set out to relate.

In the first place, the home of the Blackfeet Indians a century ago was not to the westward but on the east of the Rocky Mountains, as it is to-day. In order to reach the Pacific Coast one had to climb over that great range and enter the country of the Flatheads and numerous other tribes. Mul-tal-la had proved his enterprise as an explorer by doing this several years previous to making his longer journey to the eastward.

When Mul-tal-la left home he and his companion rode southward until well into the present State of Colorado. Then they turned east, passing through what is now Kansas and Missouri, crossing the Mississippi and entering the fringe of civilization, for they were fairly within the Northwest Territory organized a number of years before.

Deerfoot planned to take this route in reverse. Where the Blackfoot was impressed by everything he saw, he had retained an excellent recollection of the route, and this knowledge was sure to be of great help to Deerfoot and his friends. The course to be followed may be roughly outlined thus:

A little to the north of Woodvale the party would turn westward, crossing the present States of Indiana and Illinois to St. Louis. Thence they would follow the course of the Missouri to where it makes its abrupt bend northward. At that point they intended to leave it and push westward until the time came to head due north and make for the Blackfoot country. This in a general way was the route upon which took place most of the incidents recorded in the following pages.

When the border settlement dropped out of sight, the company fell into what may be called the line of march. Deerfoot was in the lead, next rode the Blackfoot, then Zigzag the pack horse, and last George Shelton, with Victor bringing up the rear. The rule was to advance in Indian file except when they reached the plains, where the topography permitted them to bunch together. In fact this lining out of the horsemen was necessary most of the time, for the trails used by them did not allow two to ride abreast. However, it permitted free conversation, so long as there was no necessity for silence.

Deerfoot led the way over a well-marked trail which was familiar to him, for he had traversed it often by day and by night. As was his custom at such times, he rode for hours without speaking a syllable. There was no call for this, but it was his habit. He heard the chat of the boys to the rear, George continually turning his head to address or listen to his brother. Deerfoot did not care, for no danger threatened any of them, and he was pleased that the couple, especially Victor, were in such overflowing spirits.

The Blackfoot showed the same peculiarity as the leader, and which it may be said is characteristic of the American race—that of silence and reserve when on the march, even while there is perfect freedom to converse. The Shawanoe would not have objected had his friends called to him, but they did not do so.

At the end of half an hour the trail, which led directly through the woods, became so level and open that Deerfoot struck his horse into a gentle trot. Bug did the same, but Zigzag did not seem to think it was expected of him, and continued plodding forward at his usual sluggish gait. The load, however, which he carried was not burdensome, and George Shelton shouted to him in so startling a voice that Zigzag broke into a trot so vigorous that it threatened to displace his pack. It is not impossible that the animal was planning for that, but the burden had been secured too well to fall.

Suddenly Zigzag swerved to the right and pushed among the trees. A sharp order from George brought him back, and then he displayed a tendency to wabble to the left. To convince him that no nonsense would be permitted, George galloped nigh enough to deliver a resounding whack on his haunch with the stock of his gun. After that Zigzag conducted himself properly.

“It seems strange, George,” said Victor, as well as his jolting horse would permit, “that only a few months ago we were in danger of our lives in this very place, and now we needn’t have the least fear.”

“All due to Deerfoot,” replied George; “the whole cause of the trouble was Red Wolf, when he started to climb that rope and it broke with him; that also broke up the plotting; with their leader gone they had no heart to try anything further in that line.”

“I spoke to Deerfoot about it, and he says the cause was more than that. Tecumseh means well, and is determined to make his warriors keep the treaty of Greenville. He did not know all the mischief Red Wolf was up to, and was in a fury when he learned it. About that time, too, Tecumseh got a hint from Governor Harrison through Simon Kenton that no more such doings would be tolerated, and he took the hint. No harm would come to us if we rode alone into any of the Shawanoe or Miami or Wyandot villages. But,” added Victor, “I’d feel a good deal better to have Deerfoot with us.”

“He’ll be as much a stranger as we after we get out of this country.”

“Still he’s an Indian and knows better than anyone else how to handle those of his race. Mul-tal-la is sure to be of good service, too.”

“Have you any idea how long we shall be gone?”

“No; and I don’t care. I feel as if I should like to spend several years on the other side of the Mississippi.”

“You’ll get homesick before that. I had a talk with Deerfoot last night and found he doesn’t expect to start on the return before next spring.”

“Will it take us as long as that to reach the Blackfoot country?”

“Of course not, but Deerfoot means to look upon the Pacific Ocean before he comes back, and that, as he figures it, is about a thousand miles beyond the Blackfoot country. According to what Mul-tal-la says, the biggest mountains in the world lie just west of his country, and we have got to climb over or get through them some way. What do you think of the plan?”

“It tickles me half to death. I wonder whether Deerfoot would care if I threw up my hat and yelled.”

“I’m sure I don’t know.”

“Well, here goes, anyway!”

And what did the irrepressible youth do but fling his cap a dozen feet above his head and emit a whoop of which Tecumseh would not have been ashamed. Both Deerfoot and Mul-tal-la looked wonderingly around, and each smiled. The Shawanoe’s smile grew broader when Victor made a grasp to catch his cap as it came down, but missed it and it fell to the earth.

“Plague take it!” exclaimed the lad, slipping out of the saddle without stopping his horse, and running back to recover his headgear.

While he was doing so Deerfoot emitted a war-whoop himself, and struck the heels of his moccasins against the ribs of Simon, who instantly broke into a gallop. Bug was hardly a moment behind him, and Zigzag, for a wonder, caught the infection. George saw what their leader was up to, and he pretended he could not restrain his own horse. The shouts he sent out while seeming to do his best frightened Jack into a gallop, and Prince proved that he did not mean to be left behind.

Thus when Victor had snatched his cap from the ground, replaced it on his head and turned to trot the necessary few paces, he saw the whole line in a gallop, with his own horse several rods in advance of him.

“Whoa! Plague take you! Whoa! Don’t you hear me?” shouted the indignant lad, breaking into a desperate run.

There could be no doubt that all the animals as well as their riders heard the command, which was loud enough to penetrate the woods for half a mile. Prince being the nearest, surely must have noted the order, but he seemed to think that, inasmuch as the horses ahead of him increased their speed, it was proper for him to do the same. At any rate he did it, and succeeded so well that his owner saw the space widening between them.

By this time Victor knew that Deerfoot was at the bottom of it all. No man can do his best when laughing or shouting, and the pursuer ceased his call and bent all his energies to overtaking the fleeing horses. He thought the leader would soon show some consideration for him and slacken his pace, but the Shawanoe seemed to be stern and unsympathizing that forenoon, for he maintained the gallop, with the others doing the same, and the task of the running youngster loomed up as impossible.

It wouldn’t do to get mad and sulk, for no one would pay any attention to him—least of all Deerfoot, who liked fun as well as anybody. Besides, the exercise promised to do the youth a world of good.

But fortune came to his relief when least expected. Victor had traveled this trail so often that he knew it almost as well as Deerfoot. He remembered it made a sharp curve to the left not far in advance. When he caught sight of the young Shawanoe, therefore, calmly galloping around the bend, the lad dived among the trees and sped at a reckless rate.

“They ain’t so smart as they think they are! I’ll beat ’em yet—confound it!”

He thought surely his head had been lifted from his shoulders, for at that moment a projecting maple limb, not quite as high as his crown, slipped under his chin and almost hoisted him off his feet. He speedily found he was intact and had suffered little more than a shock to his feelings. He was quickly at it again and soon caught sight of Deerfoot rising and sinking with the motion of his horse and the others stringing behind him.

A moment later Victor leaped into the trail, recoiling just enough to let the leader pass him as he stood. But Deerfoot reined up and stared at him as if in wonder.

“Does my brother love to wander in the woods that he should leave his saddle?” was the innocent query of the dusky wag.

“You think you know a good deal, don’t you? Wait till I get a chance; I’ll pay you for this,” was the half-impatient answer.

“Deerfoot is so scared by the words of his brother that he may fall off his horse,” said the Shawanoe with mock alarm. “Will he not forgive Deerfoot because he did not stop when he heard his brother crying behind him?”

“You go on. I’ll catch you one of these days and make you sorry.”

With an expression of grief Deerfoot started forward again, his horse on a walk. Those behind had also stopped, and they now resumed the journey. The Shawanoe kept his eye to the rear until he saw Victor was in the saddle again, when his pace immediately rose to a trot and all were quickly jogging forward as before.

George tried to look sympathetic, but he could not, and his brother saw his shoulders shaking with laughter as he rode on, not daring to trust himself to speak. By this time the impulsive Victor had rallied from his partial anger, and decided that the best thing to do was to join in the general good-nature and merriment over his mishap.

Noon came and passed, but Deerfoot showed no intention of going into camp. He humored the animals by dropping to a walk. They were allowed to drink several times from the small streams crossed, and occasionally were given a breathing spell of fifteen or twenty minutes. The Shawanoe knew how to treat their kind and did not press them too hard. When these long pauses were made the riders dismounted, lolled at the side of the trail, talked together, but neither Deerfoot nor Mul-tal-la made reference to food for themselves, and the boys were too proud to hint anything of their hunger.

When the afternoon was well advanced the party came to an open space, crossed near the middle by a sparkling brook, which issued from under some mossy rocks to the right. Early as was the season, there was considerable growth of succulent grass, which offered the best kind of nourishment for the horses. Deerfoot announced that they would spend the night in this place, and, leaping from the back of Simon, plunged into the wood in quest of game, of which they had had more than one glimpse while on the road.

Meanwhile the Blackfoot and the boys relieved Zigzag of his load, removed the other saddle and bridles, and devoted themselves to gathering wood for the night. With such an abundance on every hand this was a light task. When the leaves were heaped up, with a mass of dry twigs loosely arranged on top and larger sticks above them, George Shelton took out the sun-glass which had been presented to him by one of his neighbors. The sun was still high enough for him to catch a few of the rays and concentrate them upon the leaves, which speedily broke into a smoking flame that soon spread into a roaring fire. The method was not much superior, after all, to the old-fashioned flint and steel, but the instrument was new so far as the present owner was concerned, and he liked to use it.

One of the most treasured presents to Victor was a good spyglass that had been used by one of General Wayne’s officers throughout the Revolutionary War, and afterward in the Indian campaigns in the West. The lad had not found a good chance as yet to employ it, but when its power was explained to Mul-tal-la he was delighted and declared it would prove beyond value to them while crossing the plains, and he spoke the truth.

The fire was no more than fairly going when the report of Deerfoot’s rifle sounded not far off in the woods. No one was surprised, for game was plenty, though it was not the most favorable season, and it was safe to rely upon the dusky youth for an unfailing supply of food whenever it could possibly be secured.

When a few minutes later Deerfoot came in sight he was carrying a big wild turkey, from which he had torn the feathers, plucked the inedible portions, and washed the rest in the clear water of the brook. All that remained to do was to broil the meat over the fire and coals as soon as they were ready.

Aunt Dinah had expressed an ardent wish to stow among the bundles of the packhorse some specimens of her best cookery in the way of bread and cake, but the brothers protested so vigorously that there was neither need nor room for anything of that kind that she refrained. There was, however, considerable salt, pepper and other condiments, though neither tea nor coffee.

Deerfoot broiled the turkey without help from the others. It was cut into pieces which he toasted on green sticks skewered through them, turned over in front of the blaze and laid for a few minutes over the blazing coals. When the first piece was ready he passed it to Victor.

“That’s ’cause he feels remorse for his meanness towards me,” reflected the lad, sprinkling salt on the juicy flesh and then sinking his sharp incisors into it, realizing, as many a youngster has realized before and since, that the best sauce for any sort of food is hunger.

The next portion went to George, the third to Mul-tal-la, and last of all Deerfoot provided for himself. This was his invariable rule, and all his friends knew it so well that they never protested.

Water was brought from the brook in one of the tin cups with which they were furnished, and all made a nourishing and palatable meal.

The last mouthful had been masticated to a pulp and swallowed when Deerfoot, without a word, rose gravely to his feet and walked to where the big pack of Zigzag lay. The corners of the huge parcel had been gathered, and were tied over the middle with big knots. Under these was so large a gap that Deerfoot readily thrust in his hand without undoing the fastening. Fumbling around for several minutes he brought out a goodly sized package wrapped about with coarse brown paper.

Every eye was upon him, for all were wondering what he was seeking and had found. He carefully unwrapped the paper and then took from within something about a foot in diameter, of circular shape, three or four inches in thickness, and bulging upward in the middle. It was of a dark-brown color, the interior so full of richness that it had burst the crust in one or two places and, pushing outward, gave a glimpse of the slightly browned wealth within. Raising the object in one hand, Deerfoot broke off a piece, whose craggy sides were of a golden yellow, creamy and light as a feather. Then the others identified it.

It was a “sugar cake,” specially prepared by Dinah, and in mixing and baking it she had excelled herself. It certainly was a triumph of skill, and, despite the meal just finished, the sight of the delicious richness—with which the brothers had become familiar many a time—made their mouths water.

Deerfoot acted as if nobody else was in the neighborhood. Having broken off the golden spongy chunk, he lifted it to his mouth, and it was a wonder how fast it disappeared. The Shawanoe certainly had a sweet tooth, for his eyes sparkled as he munched the soft delicacy. In a minute or two the first segment vanished, and he instantly set to work on the second, meanwhile looking longingly at the mangled original, as if grudging the time he had to wait before disposing of that.

“Well, did you ever?” whispered Victor. “Aunt Dinah made that on purpose for him, and we were dunces enough not to take what she offered us.”

Neither of the boys was unjust enough to attribute the salute which the young Shawanoe gave the colored woman to this cause, for they knew that was impossible, but it was a sight, nevertheless, to see the fellow place himself outside of the cake. When it was about one-fourth gone he seemed to become aware that he had companions. Looking up as if in astonishment, he broke and divided the major portion between the boys. Some was offered to the Blackfoot, but he shook his head. He had never tasted of such food, and, if he knew his own heart, never would give it a chance at his interior organization.

CHAPTER III

THIEVES OF THE NIGHT.

DEERFOOT could be a stern master when necessary. While it would have been no hardship for him and Mul-tal-la to divide the duties of sentinel each night, he meant that the boys should bear their part. They were big and strong enough to do so, and there was no reason why they should not. He informed them that George was to watch the camp for the first half of the night, or rather for an hour beyond the turn, when he was to awake Victor, who would take his place until daylight. This was to be the rule throughout the expedition, except when some exigency demanded the services of the elders.

Enough fuel had been gathered to last through the darkness. It was Deerfoot’s plan to avoid the Indian villages so far as was practical, although little or nothing was to be feared from meeting those of his own race. The Blackfoot had come in contact with many tribes on his long journey eastward, but excepting in two instances nothing of an unpleasant nature occurred. You have learned that the tribes which formed the confederacy crushed by “Mad Anthony” Wayne at Fallen Timber were now so peaceably inclined toward the white settlers that not much was to be feared from them.

And yet it was not wise to tempt them too far. An Indian loves a horse, and among the tribes were plenty of thieves who would run off the animals of our friends if the chance were offered. So the latter did not mean to offer the chance.

The air was crisp, for the spring was only fairly open, and the little company that gathered round the crackling blaze called their blankets into use. The animals were allowed to crop the grass near at hand, and to lie down when they chose. None was tethered, for they were not likely to wander off, and if they showed a disposition to do so the sentinel could easily prevent it.

The four lolled about the blaze after finishing their evening meal, talking mainly of the long journey and the experiences awaiting them. Mul-tal-la answered Deerfoot’s questions again, for though the Shawanoe was well informed, his inquiries were for the benefit of the boys, whose interest naturally was keen.

When the night was well advanced, Deerfoot, without any preliminary, drew his little Bible from his hunting shirt, and leaning forward so that the light fell upon the small print, read the Twenty-third Psalm, which, you remember, was one of his favorite chapters. His voice was low, musical and reverent, and no professional elocutionist could have given the sublime passage more impressively.

The three listened attentively, none speaking during the reading. It seemed to George and Victor that they had never felt the beauty and sweetness of the book whose utterances are sufficient for every condition of man and every state of the human mind. The surroundings, the great future which spread out so mysteriously before them, the certain dangers that impended, their utter helplessness and a sense of the all-protecting care of their Heavenly Father, filled their souls as never before.

It would be hard to fathom the imaginings and thoughts of the Blackfoot. He was sitting erect, with his blanket about his shoulders, only a few paces from the young Shawanoe, and kept his eyes upon the noble countenance as the precious words filled the stillness, the listener fearful that some syllable might escape him. He had learned much of the true God in his talks with the devout youth, and, like him, had fallen into the habit of praying morning and evening, and sometimes for a few moments in the busiest part of the day.

The brothers recalled that loved parent who had been lying in his grave for weeks, and remembered how he had prayed and how triumphantly he had passed away when the last solemn moment arrived, and both firmly resolved from that time forward so to live that there could be no question of the reunion that to both was the dearest, most joyous and thrilling hope that could possibly fill their hearts.

While the two sat beside each other, silent and listening, George gently reached out his hand. Victor saw the movement, and, taking the palm within his own, fervently pressed it. At the same moment the brothers looked into each other’s eyes. It was enough; volumes could have said no more.

Deerfoot finished, and, closing the book, returned it to its resting place over his heart. Then without a word he turned and knelt on the cool earth. Instinctively the three did the same and all prayed.

Not a word was heard, but heart spoke to heart, and all communed with Him whose ear is never closed against the petition of his children. Had either of the boys prayed aloud he would have stammered, for he could not have shaken off the question as to how his words impressed his companions. It is the impossibility in many cases of one freeing himself from this hindrance that makes the sentences of the petitioner halt and stumbling, because to a certain degree they are addressed to men rather than directly to the Father. The Blackfoot would have found it almost impossible to shape intelligently his sentences if he spoke aloud, but he could talk freely in his own way to his Maker. Deerfoot could have done far better than any of the others, for he would not have hesitated, but he preferred the silent petition, and rarely spoke his words unless he was asked to do so or a special necessity existed.

The others took their cue from him, and when they heard the gentle rustling which showed that he had resumed his sitting posture they did the same. Then he nodded to George, who, rifle in hand, walked softly out in the gloom to where the animals had lain down for the night, in the midst of the grass and near the rippling brook. As he did so he bade his friends good night, and they disposed of themselves in the usual way, each with his blanket wrapped about him and his feet turned toward the fire. Within ten minutes every one of the three was sunk in sweet, refreshing slumber.

The night was clear and studded with stars. There was no moon, the gloom being so deep that the watcher could see only a few paces in any direction. Often as he had spent the night in the dim solitudes, sometimes with danger brooding and again when all was tranquil, he could never cast off the emotions that filled his being when he stood thus alone, with friends dependent perhaps upon his vigilance. He listened to the soft rippling of the brook, the hollow stillness of the vast forest, like the moaning of the far-away ocean which has been called the voice of silence, the occasional restless movement of one of the horses, and the gentle stir of the night wind among the bursting foliage overhead and around him. Then he looked toward the fire at the dimly outlined forms, partly within and partly without the circle of illumination, and again his heart was lifted to the only One who could ward off danger from him and his friends.

The youth marked out a beat for himself parallel with the brook and two or three rods in length. Sometimes he paused and, leaning on his gun, peered into the hollow gloom which inclosed him on every hand. He knew that so long as he kept on his feet he would not fall asleep, but if he sat down the lapse was inevitable. Better still to walk to and fro, as is the practice of the sentinel, for while doing so he was safe against the insidious weakness which steals the senses from the most rugged man ere he is aware.

George did not believe that any danger threatened the camp unless of the nature hinted by Deerfoot. It might be that some wandering Miamis or Wyandots or Shawanoes had observed the little party and their horses and cast covetous eyes upon the latter. If so, they would not dare to proceed to violence, but might try to run off one or two of the animals, hoping to get far enough away with them before discovery of the theft to make pursuit useless. It was this apprehension which kept the youth alert and watchful.

George Shelton had paced to and fro for more than an hour without hearing or seeing anything to excite misgiving. The cry of a wolf in the distance and the nearer scream of a panther were given scarcely a thought, for both were too common to cause alarm.

The first disturbance came from the action of his horse Jack, who had lain down at a point farther off than the others. All the animals seemed to be resting quietly, when, at the moment the lad was nearest his own and was about to turn to retrace his steps, Jack raised his head and emitted a slight whinny, though none of the others showed any disquiet.

The sentinel paused and looked at his pony, dimly outlined in the darkness. He saw he had raised his head and appeared to be interested in something on the other side of the brook. George lifted the hammer of his rifle, suspecting that some prowling wolf or other wild beast was trying to creep nigh enough to assail the horses. The youth peered into the gloom and listened, but all remained as silent as the grave.

He held his motionless position for several minutes, in doubt what he ought to do, if indeed he could do anything. Then with rare courage he began slowly walking toward the point in which Jack seemed interested, holding his gun ready to raise and fire on the instant.

He reached the brook and was about to leap lightly across when the figure of an Indian rose from the grass and stood revealed hardly ten feet distant. He did not move, and seemed to have come up from a hole in the earth. The sight was so startling to the lad that he stopped abruptly and exclaimed in a low tone:

“Helloa! Who are you?”

“Howdy, brudder?” replied the redskin in the same guarded voice.

“What do you want, stealing into our camp like this!”

“Me Par-o-wan—friend of paleface—me brudder.”

“You haven’t told me what you want,” repeated the impatient youth, with his gun half raised, for he was suspicious, and saw that the other held a rifle almost in the same position as his own.

“Par-o-wan brudder; sit down—talk wid brudder—lub brudder.”

“Dog of a Miami! leave at once! You have others with you! If you tarry we shall shoot every one of you!”

It was not George Shelton who uttered this warning, but Deerfoot, who appeared at his side so suddenly and noiselessly that the lad had no thought of anything of the kind until he heard the familiar voice.

“Par-o-wan friend ob Deerfoot—he no hunt him—he go away,” replied the Miami, plainly scared by the words and manner of the young Shawanoe, who now raised his rifle to a “dead level” and acted as if he meant to fire.

“Deerfoot knows you and those that are with you, Par-o-wan! You are the thieves who have come to steal our horses. Go quick or I shoot!”

In a panic of fear the Miami wheeled and dashed off so fast that he threshed through the undergrowth and wood like a frightened wild animal. Deerfoot waited a minute in the same vigilant attitude, and then quietly remarked:

“They will trouble us no more. Now Deerfoot will sleep.”

“But tell me what woke you; I didn’t give any alarm,” said the mystified George Shelton.

“My brother spoke. Deerfoot heard his voice. My brother is watchful, but he will not be troubled again by the Miamis, for they are alarmed.”

And without anything further the Shawanoe walked silently back to his place by the camp-fire, drew his blanket around him and five minutes later was sleeping as peacefully as before he was awakened by the soft voices of the man and boy.

“Well, that beats all creation!” muttered the grinning lad, as he resumed his pacing to and fro. “We didn’t make enough noise to wake a sleeping baby, but he must have been roused by the first word, for he was at my side in a few seconds. I don’t see the need of putting one of us on guard when Deerfoot wakes up like that. He’s a wonder and no mistake.”

So full was George’s faith in the young Shawanoe that he was absolutely sure nothing more was to be feared from the Miamis who had evidently stolen up to the camp with the intention of running off one or more of the horses. He paced regularly over his beat until certain it was well past midnight, when he went up to the fire, threw more wood on it and touched the arm of his brother.

You know that when you sink into slumber with the wish strongly impressed on your mind of awaking at a certain minute, you are almost sure to do so, or at least very near the time stamped on your brain. While George Shelton was in the act of stooping to rouse Victor the latter opened his eyes and rose to the sitting posture.

“I’m ready,” he said softly, coming to his feet, gun in hand. “Have you seen anything, George?”

The latter quickly whispered the particulars of the little incident already told.

“Well, if Deerfoot said they won’t be back, they won’t be back; but I mean to keep a lookout for them.”

With which philosophical decision Victor strolled out to the beat whose location his brother had made known to him. While gathering the blanket about him to lie down George glanced at Deerfoot, who lay within arm’s length. At that moment one of the embers at the base of the fire fell apart and the flare of light fell upon the face of the Shawanoe.

George saw that his large dark eyes were open, and no doubt he had heard every word of the cautious bit of conversation between the brothers. He did not speak, however, and immediately closed his eyes again, no doubt dropping off to sleep as quietly as before. It was a considerable time before George slumbered, for the experience of the evening, even though it amounted to little, touched his nerves. Finally he glided off into the land of dreams.

Victor did his duty faithfully, as his brother had done, and with his senses keyed to a high tension, but not the slightest disturbance occurred. Deerfoot was right in his declaration. If Par-o-wan had companions they had been too thoroughly frightened to risk rousing the anger of the Shawanoe.

The latter acted as provider again and furnished his friends with another meal upon wild turkey, promising to vary the diet in the course of a day or two, though no one felt like complaining, since there was an abundance for all, and such meat is not to be despised, even though one can become tired of it.

Thus early in their venture our friends met with a disagreeable experience, for though the day dawned with the sun visible, the temperature fell and a cold, drizzling rain set in, which promised to last for hours. Deerfoot read the signs aright, and before the rainfall began conducted his companions to a rocky section a little way off the trail, where they found shelter for themselves and partial protection for their horses. Had there been an Indian village within easy distance they would have made their way thither, being sure of a welcome.

It was not the cheerless day itself that was so trying, for that was much improved by the fire they kept going, but it was the enforced inaction. Few things are harder to bear than idleness when one is anxious to get forward. The boys fretted, but Deerfoot and Mul-tal-la accepted the situation philosophically, as they always accepted the bad with the good. No murmur would have been heard from either had they been halted for several days. Deerfoot, indeed, had reached that wise state of mind in which his conscience reproved him for complaining of anything, since he knew it was ordered by One who doeth all things well.

CHAPTER IV

AN ACQUAINTANCE.

THE cold, dismal, drizzling rain lasted without cessation till night closed in. The horses were allowed to graze sufficiently to satisfy their hunger, but they shrank shivering under the lee of the rocks, where they were only partly protected. Every member of the party proved his sympathy by covering an animal with his blanket, an extra one being provided for Zigzag, so that after a time all became comfortable. The fire that was kept blazing on the stony floor under a projecting ledge warmed the four so well that they were able to get on quite well without additional covering.

Mul-tal-la asked the privilege of going off on a hunt in the afternoon. His bow was at disadvantage in the wet, and he borrowed Deerfoot’s rifle, with which he had practiced enough to acquire a fair degree of skill.

“What will my brother bring back?” asked the Shawanoe.

“Whatever his brothers want,” replied the Blackfoot in good English. He looked first at Deerfoot for his request.

“Let my brother bring a buffalo,” he replied, knowing very well that none was in the neighborhood.

“Mul-tal-la would have to journey too far,” said the warrior, who had acquired from his friend the habit of speaking of himself in the third person; “but if Deerfoot wants it he will hunt till he finds a buffalo.”

“Then let my brother bring anything,” added the Shawanoe significantly, as if he doubted the ability of his friend to shoot any kind of game. That was the impression, too, he meant to make.

The Blackfoot turned to the boys.

“I’m not particular,” remarked George, who was inclined to sympathize with the homely but good-natured fellow.

“What would my brother like more than anything else?” persisted Mul-tal-la.

“I think a meal of venison would taste good. What do you say, Victor?”

“Nothing can suit me better,”

“My brothers shall eat deer’s meat when Mul-tal-la comes back”, was the confident comment of the hunter.

Deerfoot looked alarmed.

“Let not my brother wait till he shoots a deer,” he said.

“Why shall he not wait?”

“Because my brother may never come back if he waits for that,” was the slurring explanation of the young Shawanoe. The Blackfoot grinned almost to his ears, displaying a set of teeth that rivaled those of the Shawanoe. No one could accept a joke better than this dusky wanderer from the Rocky Mountains.

Mul-tal-la had not been gone more than a quarter of an hour when the report of his gun was heard. Deerfoot smiled and wondered what the result had been. But it was Mul-tal-la’s moment of triumph when, soon after, he came in sight bending under the weight of the forequarters of a goodly sized deer. He had come upon three of the animals as they were plucking the tender shoots of the young trees and undergrowth. The meeting was as much of a surprise to him as to the deer themselves. A hunter could not have asked a fairer shot, and as the three terrified creatures whirled about to make off, he sent a bullet into one just back of the fore leg and brought him down.

No one ever saw the proud Blackfoot do more amazing grinning than when he emerged from the woods and flung the carcass at the feet of the Shawanoe.

“Now, if my brother wishes Mul-tal-la to bring him a buffalo, he will do so.”

Deerfoot reached out his hand and shook that of the Blackfoot.

“Mul-tal-la is a great hunter. He brings back that which he goes out to seek. Deerfoot is sorry that he said doubting words.”

“Oh, he needn’t worry, for Mul-tal-la cares not for his idle talk.”

The prospect of a clear day on the morrow and the bountiful meal of venison, even though it was perhaps fresher than was desirable, put all in the best of spirits. The evening passed much as the previous one. The boys made themselves a bed of boughs that had been dried by the heat of the fire, and slept undisturbed till morning, the Indians acting the part of sentinels and not being disturbed through the night.

The morning came bright, mild and sunshiny. The breakfast was eaten early, and the sun had hardly risen when the little cavalcade was in motion. Deerfoot now made an abrupt turn to the left, and by nightfall had penetrated a goodly distance into the present State of Indiana. The pace was a walk and was maintained until night began closing in. Then followed days so similar to one another that it would be monotonous to give the history of each. The adventurers were compelled to cross a number of streams, several of considerable size, but, by searching, fords or shallow places were found where the horses waded without submerging their riders and without making it necessary to unload Zigzag and transport his burden on a raft. This good fortune, however, could not be expected to last. The rivers that interposed were sure to prove the most serious obstacles in their path.

Most of the time Deerfoot was able to discover well-marked trails, which he turned to account if they led in the right direction. A curious sight was the “salt licks” which now and then they came upon. Sometimes these covered more than an acre and marked where the brackish water, oozing upward, left a fine incrustation of salt, of which all kinds of animals are very fond. Some portions had been licked over hundreds and perhaps thousands of times by the buffalo, deer, bears, wolves and other beasts, until they were worn as smooth as a parlor floor. The horses of our friends were allowed to do considerable lapping for themselves, for they appreciated the privilege.

Hardly a day passed on which strange Indians were not met. None showed any hostility, and responded to the signs of friendship always made by Deerfoot at first sight of them. These signs are so universal among the red men that a native of the American coast could readily make himself understood by an Indian on the banks of the Pacific. The Shawanoe kept to his rule of avoiding villages so far as he could. While he felt little fear for himself and companions, he thought the horses were likely to arouse the cupidity of the strangers, with the result that some of the animals would be stolen or unpleasant consequences would flow from the meetings.

So, with now and then an unpleasant variation in the weather, but never checked for more than an hour or two, and heading slightly to the south, the party steadily progressed until in a little less than a week they passed out of the section now known as Indiana into that of southern Illinois. Straight across this they rode, still crossing the interposing rivers, sometimes with the help of a raft, with the horses swimming alongside, but oftener by wading. They found the Indians of this section inclined to be rovers, and it was generally easy to find the fords used by them. Pushing steadily on, with the spring rapidly advancing on every hand, and with fine weather most of the time, our friends finally came to the banks of the mighty Mississippi, at a point directly opposite St. Louis.

This city, which to-day is one of the leading ones in the Union, was at that time an unsightly collection of cabins and wooden houses strung along the river. Founded long before by the French as a trading post, it had not developed much beyond that when visited by Deerfoot and his companions. The Mississippi was broad, muddy from recent freshets and rapid. Looking across to the town the Shawanoe declared that it would not do to attempt to swim the river, though the task was not impossible.

It was early in the forenoon when they came to the Father of Waters, and they began making signals to those on the other side to come to their help. There were plenty of boatmen who turned an honest penny in this way, and the party was not kept waiting long. A broad flat boat, with a square sail, was seen to put out from the wharf, and the two occupants began laboring with might and main. They used long poles for most of the distance, for the wind was more favorable for the return, then swung big paddles, and so at last brought the awkward craft to the eastern bank.

The situation was complicated at first because the couple were Frenchmen who could hardly speak a word of English, but it was easy to make them understand that their services were needed to place the party in the town on the other bank. George and Victor Shelton had a moderate supply of Spanish silver—that country still claiming the territory—and Deerfoot carried some. The Blackfoot, of course, had nothing of the kind. The price asked by the Frenchmen was moderate, and men and animals went aboard.

Horses and owners proved a dangerously heavy cargo. The looks of fear showed on the faces of the voyageurs, as they were by profession, when Zigzag, the last, stepped gingerly aboard with his load. Even Deerfoot was anxious, for the flatboat sank near to its gunwales. Fortunately a moderate breeze was blowing in the right direction, and by trimming boat and using care the party made the passage without mishap.

On the western bank our friends found themselves in a motley and interesting community. The chief business of St. Louis, as it continued to be long afterward, was trading in furs. From that point boats ascended the Mississippi or, a short distance above, turned off up the Missouri, the big brother of the great stream, carrying with them hunters and trappers, some of whom remained for long months in the wild regions of the Northwest. When the voyageurs, with their rhythmic songs and vigorous swing of their oars, came down the river again, they brought with them valuable loads of peltries, which found ready sale at the post. The pay received by these hardy adventurers, and which represented in most instances toil, privations and perils extending through many weary weeks, was, as a rule, speedily wasted in riotous living. Penniless, remorseful and without credit, the hunters and trappers had no choice but to make off again, returning in due time to repeat their folly, or mayhap to fall victims to the treachery of the red men whose territory they invaded.

The visitors attracted less attention than they expected. Indians and white hunters were too common a sight in St. Louis to be remarked upon. Perhaps if the inhabitants had known that the last visitors were on their way to the other side of the continent they would have given them more heed, but, on the advice of Deerfoot, the secret was kept from all chance acquaintances.

When Mul-tal-la and his companion came down the Missouri in a canoe it was easy enough to transport themselves to the eastern bank. They obtained the boat in the country of Iowa Indians, and, leaving it on the eastern bank, never saw it again.

As a good deal of the day remained the travelers ate their noon meal at one of the taverns, where the food was less inviting than the game secured by their own rifles, and then remounting, they headed across the country for a hamlet named La Charrette, about which they had made inquiries and learned that it was the last white settlement on the Missouri. It was too far to reach that day, but they expected to make it on the morrow if no check occurred. Even though they were so near St. Louis they found no lack of game, and the question of food gave them the least concern of any. The Blackfoot, however, had told his friend more than once that they were to reach sections where the matter would be found one of considerable difficulty.

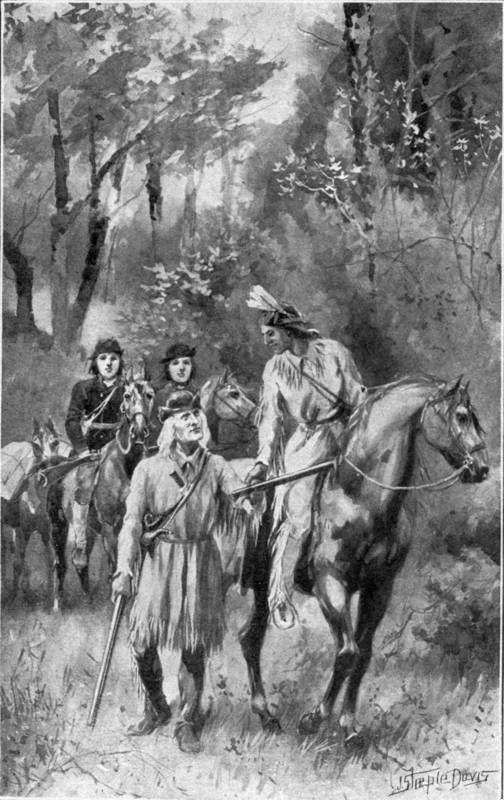

La Charrette proved to be a dilapidated hamlet of half a dozen log cabins, standing close to the river. The country was so open when they approached the wretched dwellings that our friends were riding in a bunch, with Zigzag a little to the rear. Several half-clothed children were seen playing in the mud near the water’s edge, but no one else for the moment was visible. Deerfoot had just remarked that he was so unfavorably impressed with the appearance of the little settlement that they would not stop, as had been his intention, when a man was seen to come out of the door of the nearest cabin. He carried a long rifle, was dressed in the costume of the hunters of Kentucky, and was as straight and erect as an Indian. He paused and looked down at the children, apparently unaware of the approach of the horsemen.

Victor, who was riding at the elbow of Deerfoot, heard him utter an exclamation of astonishment. Turning his head, he saw the Shawanoe intently studying the man who had just come into view. The next moment Deerfoot made another exclamation, and, leaping from his horse, ran toward the other. The latter was quick to detect the sound of his footsteps, and turned to look at him. As he did so the boys gained a fair view of his face. He had a somewhat elongated countenance, was smoothly shaven, with a prominent nose, and seemed to be in middle life.

It was evident that he recognized Deerfoot before the latter reached him. The man was seen to smile, stride forward and warmly grasp the hand of the dusky youth, while the two talked fast, though their words could not be overheard.

“They seem to be old acquaintances,” said the wondering Victor. “I don’t see how that can be, for Deerfoot has never been in this part of the country.”

“But the man may have been in ours. I never saw him before; have you?”

The hunter had turned his gaze from the face of Deerfoot, apparently because of something said by him, and was looking at the Blackfoot and the brothers, who were approaching with their horses on a slow walk. Deerfoot also turned and beckoned the boys to draw near. They did so, scrutinizing the stranger, whom they certainly had never seen until then.

To their amazement the young Shawanoe introduced them to Daniel Boone, the most famous pioneer of the early West. The boys had heard of him times without number, for he was an old acquaintance of their father, and they knew how intimate he and Kenton had been. He was genial and pleasant, although always inclined to reserve, and insisted that the company should dismount and spend the rest of the day and night with him.

Daniel Boone and Deerfoot.

It was hard to refuse, but the signs of poverty, and especially the sight of several wan faces peering through the broken windows, decided Deerfoot that it would be more considerate for them to make excuse. The presence of so many, even if divided among several households, could not but be burdensome.

But the boys dismounted and walked with Deerfoot and Boone to the cabin from which the pioneer had emerged, and found seats on the broken-down porch. The Blackfoot preferred to stay where he was and look after the horses.

The talk was one that the boys remembered all their lives. The sight of Deerfoot, who was as well known to Boone as to Kenton, seemed to warm the cockles of the pioneer’s heart, and he talked with a freedom that would have astonished his friends. Deerfoot did not hesitate to tell him of the destination of himself and boys and the long venturesome journey before them. The mild blue eyes lit up.

“I wish I could go with you!” exclaimed Boone.

“Why can’t you?” asked Deerfoot. “It will make all our hearts glad.”

The great ranger shook his head.

“No; I’m too old.”

“Why, you can’t be more than fifty, if you are that much,” said the impulsive Victor.

With a smile that showed his fine, even teeth, Boone said:

“Fifty years ago I was older than Deerfoot is now, for I’m close to three score and ten. I do a little hunting, as I expect to do to the end of my life, but I couldn’t stand such a tramp as you have started on, my friends. Howsumever, it’s the best thing in the world for these youngsters, and they couldn’t have better company than Deerfoot.”

“We found that out long ago,” said George Shelton warmly. “If it hadn’t been for him, my brother and I would have never lived to be here.”

“My brother shouldn’t talk that way,” protested the Shawanoe with a blush.

“Haven’t you always told us to speak the truth?” asked Victor. “And you know what George just said is as true as it can be.”

Deerfoot would have liked to deny it, but he could not. Nevertheless, it was not pleasing to listen to praise of himself, as, I am forced to say, he was often compelled to do. He shook his head and looked at Boone.

“How long has my brother lived here?”

“Between two and three years. I expect to stay with my relatives till I die.”

The veteran again urged the company to remain over night with him. Their presence had already drawn the attention of every inhabitant of the hamlet. Boone remarked that most of the men were off hunting, but loungers were noticed in front of several of the cabins staring curiously at the visitors, while the women and children did most of their gaping from the windows. Most of these were composed of oiled paper punched through by soiled fingers, but several had been furnished with glass, and there seemed hardly a single sound pane among them all.

Fearing that the people would crowd closer, as they were beginning to do, Deerfoot took advantage of the renewed invitation to rise to his feet and say that it was time they were on the way again. Throughout the interview the Blackfoot sat on his horse gazing indifferently to the westward, as if he discovered nothing of interest in any direction.

Boone warmly shook the hands of Deerfoot and the boys, and waved them good-bye as they rode away.

You have learned something of Daniel Boone, the great pioneer of Kentucky, though, as I have told you, Simon Kenton was his superior in many respects. Boone was earlier on the ground, being considerably older than Kenton, and that fact helped his fame. He was a colonel in the United States Army, and went to Kentucky before the opening of the Revolution. In 1793 he removed to Upper Louisiana, which at that time belonged to the Spaniards, who appointed him a commandant of a district. It is worth adding, in conclusion, that both Boone and Kenton lived well beyond four-score. There is no denying that an out-door life is healthful and tends to longevity, even though, as in their cases, it was attended with privation, suffering and no little danger.

CHAPTER V

A CLOSE CALL.

NOW you must not forget that most of the names of rivers, mountains and settlements which I use in this story had no existence when Deerfoot and his friends started on their journey across the continent. A large number of these names were bestowed by Captains Lewis and Clark, who came after the little party. Some of the titles have stuck, and a good many have undergone changes. It was these explorers who gave the Rocky (then known as Stony) Mountains their name, to say nothing of other peaks and ranges. Lewis and Clark showed much ingenuity in making up the long list, and it must be admitted that in many instances the change of title since then was not an improvement.

Our friends left the Missouri some distance beyond old Fort Osage, where the stream changes its course, and instead of flowing directly east, comes from the north. They headed a little south of northwest, and when we look upon them again the four were in the western part of the present State of Kansas and below the Arkansas River. Had they turned south they would have had to cross only a comparatively narrow neck of Oklahoma to enter the immense State of Texas.

By this time it was early summer and the region was like fairyland. The surface was rolling prairie, and the luxuriant grass was dotted with an exuberance of wild flowers, brilliant, beautiful and fragrant, while the soft blue sky, flecked here and there by snowy patches of cloud, shut down on every hand. North, south, east, west, every point of the compass showed the same apparently limitless expanse of rolling prairie, watered by many streams and fertile as the “Garden of the Lord.”

The party had become accustomed to the varying scenery which greeted them from the hour of leaving their distant home, and especially after crossing the Mississippi, but they were profoundly impressed by the wonderful loveliness on every hand. Mul-tal-la had passed over the same ground before, but it was not clothed in such enchanting verdure. Not a single tree was in sight, but the grass in some places brushed the bellies of the horses, and no one needed to be told that at no distant day the region would become one of the most prosperous on the continent.

At intervals the horsemen came to higher swells in the prairies, upon which they halted and surveyed the surrounding country. While the weather was warm, there was just a touch of coolness which made it ideal for riding, walking or, in fact, living and drawing one’s breath.

The best of fortune had attended the little company thus far. There had been some delays and checks in crossing the streams, and once Zigzag’s stubbornness came within a hair of losing the contents of the pack strapped to his back. Bug, the horse of Mul-tal-la, wandered off one night, and he, too, developed such a spell of obstinacy that it was a whole day before he was found again. Had he not been recovered just when he was he would have been run off by a party of Pawnees, who seemed disposed to make a fight for him. These warriors were large, finely formed and numerous enough to wipe out the four, but the exercise of tact finally adjusted matters, and nothing more of an unpleasant nature occurred.

But, without dwelling upon these and other annoying incidents, we find our friends in the section named on this bright, sunshiny forenoon in early summer, riding at a leisurely gait toward the setting sun, for the time had not yet come to turn northward and make for the hunting grounds of the Blackfeet.

Deerfoot checked his horse on the crest of the moderate elevation, with one of the brothers on either side of him, and Mul-tal-la farther to the left. All carefully scanned the horizon and the grand sweep of prairie that inclosed them on every side.

“Do my brothers see anything more than the stretch of plain?” asked Deerfoot.

Naturally one of the first things done by George Shelton at such times was to bring his spyglass to his eye. It was a good instrument and proved of value to all. He had been thus engaged for several minutes when the Shawanoe asked his question.

“No,” was the reply. “There seems to be no end to waving grass and shining flower.”

“Let my brother look to the northward,” said Deerfoot, pointing in that direction, “and tell me what he sees.”

George did as directed. At first he saw nothing unusual, but as he peered he observed a change in the color of the landscape. Far off toward the horizon he noted, instead of the variegated hue, a dark sweep, as if the prairie ended on the shore of a dun-colored lake or sea. It covered thirty degrees of the circle. His first thought was that it was a large body of water, for as he studied it closer he perceived a restless pulsation of the surface, which suggested waves, though there was not a breath of wind where the company had halted.

“It looks to me like a big body of water,” said the boy, lowering his glass.

“Let me have a squint,” remarked Victor, reaching for the glass, which was passed to him.

Deerfoot and Mul-tal-la did not speak, but exchanged significant looks.

Victor held the glass to his eyes for several minutes, while the others waited for him to speak.

“It looks like a body of water,” he finally said, without lowering the instrument, “but, if it is, it’s coming this way!”

It was the Blackfoot who grinned and uttered the single word:

“Buffaloes!”

“So they are! You might have known that, George.”

“You didn’t know it till Mul-tal-la told you.”

Very soon the animals were identified by the naked eye. Numbers had been seen before, but never so large a herd as that upon which all now gazed with rapt attention. There must have been tens of thousands, all coming with that heavy, plunging pace peculiar to those animals. Sometimes an immense drove would be quietly cropping the herbage, when a slight flurry would set several in motion. Then the excitement ran through the whole lot with almost electric suddenness, and all were soon plunging in headlong flight across the plain.

The buffalo, or more properly the American bison, is a stupid creature and subject to the most senseless panics. Thousands have been known to dash at the highest speed straight away. Sometimes the leaders would come abruptly to the top of a lofty bluff, perhaps overlooking a stream deep below. In vain they attempted to hold back or to swerve to one side. The prodigious pressure from the rear was resistless, and they were driven over the cliff into the water, with the others piling upon them, and those again borne under by the remainder of the herd until hundreds were trampled, smothered and drowned in the muddy water beneath. Only those at the extreme rear were able to save themselves, and that not through any wit of their own.