Ned in the Block-House: A Tale of Early Days in the West

Edward S. Ellis

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

The Tell-tale Arrow.

BOY PIONEER SERIES.

Ned in the Block-House.

A TALE OF

EARLY DAYS IN THE WEST.

By EDWARD S. ELLIS,

AUTHOR OF "FIRE, SNOW AND WATER," "PERSEVERANCE PARKER," "A

YOUNG HERO," "SWEPT AWAY," ETC., ETC.

PHILADELPHIA:

HENRY T. COATES & CO.

"Mr. Ellis's works are favorites and deserve to be. He shows variety and originality in his characters; and his Indians are human beings and not fancy pieces."—NORTH AMERICAN REVIEW.

Copyright, 1883, by Porter & Coates.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

| In the Forest | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Boy Pioneer—Deerfoot, the Shawanoe | 18 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Old Friends | 32 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Through the Trackless Forest—The Cause | 46 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| "Shut Out" | 60 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Block-house | 73 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Message | 87 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Opening Communication | 101 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Within the Block-house | 126 |

| CHAPTER X. PAGE | |

| Flaming Messengers | 140 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| In Great Peril | 154 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| "Birds of the Night" | 168 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Shadowy Visitors | 182 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| A Mishap and a Sentence | 196 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| An Unexpected Visitor | 212 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Out-doors on a Dark Night | 226 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Long Clearing | 247 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| The Fiery Enemy | 265 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The Tug of War | 282 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The South Wind | 298 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Conclusion | 312 |

NED IN THE BLOCK-HOUSE.

CHAPTER I.

IN THE FOREST.

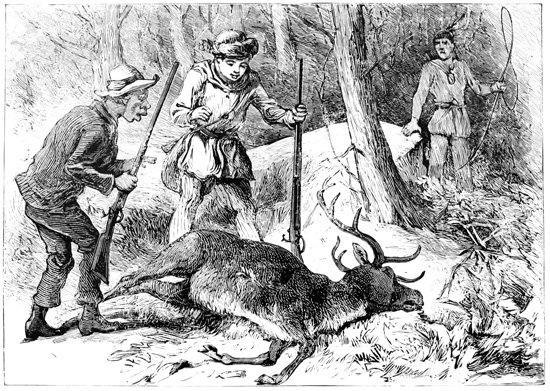

"Now you've got him, Ned!"

"Sh! keep quiet!"

The boy who was addressed as Ned was kneeling behind a fallen oak, in a Kentucky forest, carefully sighting at a noble buck that stood in the middle of a natural clearing or opening, with head upraised and antlers thrown back, as though he scented danger, and was searching for the point whence it threatened.

The splendid animal was no more than a hundred yards distant, so that no better target could have been offered. He was facing the youth, who aimed at the point above his fore legs, which opened the path to the heart of the creature.

The lad, who was sighting so carefully, was Ned Preston, and his companion was a colored boy with the unique name of Wildblossom Brown. There was not a week's difference in their ages, each having been born four years before the immortal Declaration of Independence. As the date on which we introduce him to the reader was the autumn of 1788, the years of the two may be calculated without trouble.

Ned Preston, as he drew bead on the deer, was as certain of bringing him down as he was of "barking" the gray squirrel, when it chirped its mimic defiance from the topmost limbs of the gnarled oak or branching sycamore.

Wildblossom, or "Blossom," as he was invariably called, was anxious that his young master should not miss, for the chilly autumn day was drawing to a close, and they had eaten nothing since morning. They were eager to reach the block-house, known as Fort Bridgman, and scarcely allowed themselves any halt for many hours; but night was closing in, and they must soon go into camp; food was therefore as indispensable as fire.

The deliberation of Ned Preston led Blossom to fear the game would bound away before the trigger was pulled. When, therefore, the African saw the long brown barrel pointed for several seconds at the animal, he became impatient, and uttered the words given above.

The next moment there was a flash, and the buck made a prodigious bound, dashed straight toward the fallen tree behind which the boys were crouching, and fell within fifty feet of them.

"Dar's our supper suah's yo' born!" shouted the delighted negro, making a strong effort to leap over the prostrate oak so as to reach the game ahead of his companion. He would have succeeded if the oak had lain somewhat nearer the ground. As it was, he landed on his head and shoulders, and rolled over; but he was unharmed, and scrambling to his feet, ran to the deer.

Ned Preston was but a brief distance behind him, trailing his long rifle, walking rapidly, and very much puzzled over what was certainly an extraordinary occurrence; for although he had aimed at the buck, pulled the trigger, and the game had fallen, yet the astonishing fact remained, that Ned had not fired his gun.

Blossom Brown in his excitement did not notice that there was no report of the weapon—that, in short, the flint-lock (percussion guns being unknown at that day) had "flashed in the pan." When he saw the frantic leap and fall of the animal, he supposed, as a matter of course, it had been killed by the bullet of his young master; and if the latter had not stopped to examine his piece, he might have believed the same, so exactly did the wounding of the game accord with the useless click of the lock and flash of the powder.

"I didn't shoot that buck," called out Ned, as he ran up behind Blossom; "my gun wasn't fired at all."

"Dat hasn't got nuffin to do with it," was the sturdy response of Blossom, who was bent on having his meal without any unnecessary delay; "you p'inted de gun at him, and he drapped; dat's sufficacious."

"But I didn't kill him," insisted Ned, more determined on solving the mystery than he was on procuring supper.

"I tell you dat you did—no, you didn't!"

At that instant Blossom, who had drawn his hunting-knife, stooped over to apply it to the throat of the buck, when he gave an unexpected flirt of his head, bringing his antlers against the boy with such violence that he was thrown backward several feet. When Blossom found himself going, he made his last remark, inasmuch as the deer just then proved he was alive in a most emphatic manner.

But it was the last expiring effort, and the negro approached him again, knowing that all danger was past.

"De way ob it was dis way," he added, turning partly around so as to face his friend, who was examining his rifle as he poured powder from his horn into the pan; "you p'inted dat gun ob yours at de buck, and as he war lookin' dis way he seed you frough de bushes, and he knowed it war no use; so he jes' made a jump into de air, and come down pretty near dead, so as to sabe you de expense ob firin' off de powder, which aint very plenty in Kentucky."

This explanation seemed to satisfy the one who made it, but not his listener, who knew that the game was brought to earth by some one else.

And yet he was sure he had not heard the report of any other gun at the moment the animal seemed to have received its death-wound, so that it would seem some other cause must have ended its career.

While Blossom was working with his knife, Ned caught sight of something which gave him a suspicion of the true cause. The game lay on its side, and that which arrested the eye of the youthful pioneer was the feather of an Indian arrow.

"Turn him over," said Ned; and the lad, wondering why he told him to do so, complied.

The truth was then made known. From the side of the buck protruded a few inches of the shaft of an Indian arrow, to which the eagle's feather was attached. The flinty head had been driven clean through the heart and some distance beyond, so that the sharp point must have been near the surface on the other side.

The deer scarcely ever is known to fall instantly, no matter how it is shot; so that, with such a formidable weapon dividing the very seat of life, it still ran several rods before falling.

When Blossom saw the arrow his appetite vanished. He stooped over, staring at it a moment, and then suddenly straightened up and exclaimed:

"Let's run; dis aint any place for fellers like us!"

And, without waiting for the advice of his young master, the negro lad caught up his gun and made a dash for the prostrate tree from which he had rushed when the buck first fell.

Ned Preston was frightened beyond expression, for that which he had discovered was proof positive that one red man at least was close at hand; and when the American Indian was encountered in the Kentucky or Ohio forest, in the year of our Lord 1788, it was wise to consider him the most dangerous kind of an enemy.

Ned had poured the powder in his priming-pan and shaken it into the tube before he caught sight of the arrow, for he had been instructed, from the first day he carried a gun, that, after discharging the piece, he must not stir from his steps until it was reloaded and ready for use again.

The moment he understood what killed the buck he looked around for the Indian who did it. He could easily tell the direction whence the missile came, from the position of the game when struck; but the penetrating eye of the lad could detect nothing when he turned his gaze toward that, nor indeed toward any other point.

This did not surprise him, for the nature of the Indian leads him to be secretive in all he does; and many a time has his most destructive work been done without the sufferer catching a glimpse of him.

The conclusion of Ned was that a party of warriors were in the immediate neighborhood, and that, as an inevitable certainty, he and Blossom were at their mercy. If they chose to send in a shower of arrows, or fire the guns which some of them were likely to own, nothing could save the two lads.

If they chose to rush forward and take the boys captives, it was beyond the power of the youths to escape; in fact, as Ned looked at it, the two were already as good as prisoners, and the Indians were only keeping in the background for a brief while, for the sake of amusing themselves, as a cat sometimes plays with a mouse before crunching it in her jaws.

The situation was an alarming one in every sense, but Ned Preston showed a courage that his life on the frontier had taught him was the only wise course in such a trying time. He stooped over the carcase of the deer, and carefully cutting a choice slice from it, turned about and walked deliberately back to where Blossom was awaiting him, behind the oak.

Ned's desire to break into a run and plunge off into the woods was almost uncontrollable, and the sensation of expecting every minute an Indian arrow driven into his back, while resolutely keeping down to a slow and dignified walk, was beyond description.

Blossom Brown, who had started away in such haste, so dreaded some such shot that he threw himself behind the tree, where he lay still. He was strongly led to this course by his affection for his young master, whom he could not desert even for his own benefit.

"Whar am de Injines?" asked Blossom, in a husky whisper, as his friend walked around the root of the oak and joined him.

"They can't be far off," was the answer of Ned, "and there isn't any use of trying to run away from them. There must be a war party, and when they are ready they will come and take us. So let's kindle a fire and cook the meat."

This was an amazing proposition to make, but it was acted upon at once, extraordinary as it may seem. Blossom was very nervous while gathering wood and giving what assistance he could. He continually glanced around him, and peeped furtively over the trunk, wondering why the red men did not come forward and take them prisoners.

The youths were so accustomed to camping out that it was an easy matter to prepare their evening meal. They would have preferred the venison not quite so fresh, but they were glad enough to get it as it was; and when they sprinkled some of the salt and pepper, always carried with them, on the crisp, juicy steak, it was as toothsome and luscious as a couple of hungry hunters could wish.

True, the circumstances under which the meal was eaten were not conducive to enjoyment, for no person can be expected to feel unrestrained happiness when surrounded by a party of treacherous red men, who are likely to send in a shower of arrows, or a volley of bullets, just as you are raising a piece of meat to your mouth.

And yet, despite all that, Ned Preston and Blossom Brown masticated and swallowed the last morsel of the liberal piece taken from the buck slain by the Indian arrow.

The bleak, blustery autumn day was drawing to a close, when the boys arose to their feet, uncertain what was the best to do in the extraordinary situation.

The sky had been overcast during the afternoon, though there were no indications of an immediate storm. The wind blew strongly at times, with a dull, moaning sound, through the trees, from which the leaves rustled downward in showers. Now and then a few flakes of snow drifted on the air for some minutes before fluttering to the ground. Everything betokened the coming of winter, and, though it was the royal season for game, yet there was something so impressive in the autumn forest, now that the seasons were sinking into decay and death, that Ned Preston, sturdy and practical though he was, could not avoid a feeling of sadness when he set out from his home for the Block House, thirty miles away.

"Ned, what am de use ob loafin' round here?" asked Blossom a minute after they rose from their supper. "If dem Injines don't want to come forrard and speak to us, what's de use ob waiting for 'em?"

There was some wisdom in this question, and it was one that had presented itself to Ned while thoughtfully eating his venison steak.

Was it not possible that the warrior who fired the fatal arrow believed the boys belonged to a large party of white hunters and scouts, and had withdrawn long before? Was there not a chance of getting away by a sudden dash?

Night was not far off, and if they could keep out of the hands of the red men until then there was good ground for hoping they would elude them altogether.

Nothing was to be gained by discussing or thinking over the matter, and Ned acted at once.

"Follow me," he whispered to Blossom, "and don't make any noise."

The young hunter, trailing his rifle, stooped forward as far as he could without impeding the power to walk, and then ran directly from the tree, and back over the path that had brought them to the clearing.

Blossom was at his heels, traveling quite rapidly; but glancing behind him so often, he stumbled more than once. The negro had quick eyesight, and once when he turned his head he saw something flutter in the forest behind him; then there was what seemed to be the flitting shadow of a bird's wing as it shot by with the speed of a bullet.

But at the same instant a faint whizz caught his ear, and some object whisked past his cheek and over the shoulder of the crouching Ned Preston. The African had scarcely time to know that such a thing had taken place when he heard a quick thud, and there it was!

From the solid trunk of a massive maple projected an arrow, whose head was buried in the bark; the shaft, with the eagle's feather, still tremulous from the force with which it had been driven from the bow.

The same Indian who had brought down the buck had sent a second missile over the heads of the fugitives, and so close indeed that the two might well pause and ask themselves whether it was worth their while to run from such an unerring archer, who had the power to bring them down with as much certainty as though he fired the rifle of Daniel Boone or Simon Kenton.

But neither Ned Preston nor Blossom Brown was the one to stand still when he had the opportunity of fleeing from danger. They scarcely halted, therefore, for one glance at the significant missile, when they made a slight turn to the left, and plunged into the woods with all the speed they could command.

CHAPTER II.

THE BOY PIONEER—DEERFOOT, THE SHAWANOE.

Before proceeding further it is proper to give the information the reader needs in order to understand the incidents that follow.

Macaiah Preston and his wife were among the original settlers of Wild Oaks, a small town on the Kentucky side of the Ohio, during the latter portion of the last century, their only child being Ned, who has already been introduced to the reader. Beside him they had the bound boy Wildblossom Brown, a heavy-set, good-natured and sturdy negro lad, whom they took with them at the time they removed from Western Pennsylvania. He was faithful and devoted, and he received the best of treatment from his master and mistress.

Ned was taller and more graceful than the African, and the instruction from his father had endowed him with more book learning than generally falls to the lot of boys placed in his circumstances. Besides this, Mr. Preston was one of the most noted hunters and marksmen in the settlement, and he gave Ned thorough training in the art which is always such a delight for a boy to acquire.

When Ned was thirteen years old he fired one day at a squirrel on the topmost branch of a mountain ash, and brought it down, with its body shattered by the bullet of his rifle. The father quietly contemplated the work for a minute or so, and then, without a word, cut a hickory stick, and proceeded to trim it. While he was thus employed Ned was looking sideways at him, gouging his eyes with his knuckles and muttering,

"You might excuse me this time—I didn't think."

When the hickory was properly trimmed, the father deliberately took his son by his coat collar with one hand and applied the stick with the other, during which the lad danced and shouted like a wild Miami Indian. The trouncing completed, the only remark made by the father was—

"After this I reckon when you shoot a squirrel you will hit him in the head."

"I reckon I will," sniffled Ned, who was certain never to forget the instructions of his parent on that point.

Such was the training of Ned Preston; and at the age of sixteen, when we introduce him to the reader, there were none of his years who was his superior in backwoods "lore" and woodcraft.

In those times a hunter differed in his make-up from those of to-day. The gun which he carried was a long, single-barreled rifle, heavy, costly of manufacture, and scarcely less unerring in the hands of a veteran than is the modern weapon. It was a flint-lock, and of course a muzzle-loader. The owner carried his powder-horn, bullet-pouch, and sometimes an extra flint. Lucifer matches were unknown for nearly a half century later, the flint and tinder answering for them.

Ned Preston wore a warm cap made of coonskin; thick, homespun trowsers, coat and vest; strong cowhide shoes, and woollen stockings, knit by the same deft hands that had made the linen for his shirt. The coat was rather short, and it was buttoned from top to bottom with the old style horn button, over the short waistcoat beneath. The string of the powder-horn passed over one shoulder, and that of the game-bag over the other. Neither Ned nor Blossom carried a hunting-bag, for they had not started out for game, and the majority shot in Kentucky or Ohio in those days were altogether too bulky for a single hunter to take home on his back.

Some thirty miles in the interior from the settlement stood Fort Bridgman, a block-house on the eastern bank of the Licking River. It was erected six years before the time of which we are speaking, and was intended as a protection to a settlement begun at the same period; but, just as the fortification was finished, and before the settlers had all their dwellings in good form, the Shawanoes and Wyandots swooped down on them, and left nothing but the block-house and the smoking ruins of the log dwellings.

This effectually checked the settlers for the time; but one or two courageous pioneers, who liked the locality, began erecting other cabins close to the massive block-house, which had resisted the fierce attack of the red men. The man who had charge of the fortification was Colonel Hugh Preston, a brother of Macaiah, and of course the uncle of Ned, the hero of this story. He maintained his foothold, with several others as daring as he, and his wife and two daughters kept him company.

There was a warm affection between the brothers, and they occasionally exchanged visits. When this was inconvenient, Ned Preston acted as messenger. He often carried papers sent down the Ohio to his father for the uncle, together with the letters forwarded to the settlement from their friends in the East.

On the day of which we are speaking he had, in the inner pocket of his coat, a letter for his uncle, one for his aunt, and one each for two of the garrison; so that his visit to the post was sure to be a most welcome one.

Between the settlement on the Ohio and the block-house on the Licking lay the thirty miles of unbroken forest. Ned and Blossom had made this journey in one day in the month of June, but their custom was to encamp one night on the way so as to give themselves abundance of time; and the trip was generally a most enjoyable one to them.

It must not be supposed they forgot the danger most to be dreaded was from the Indians who roamed over the Dark and Bloody Ground, and who held almost undisputed possession of hundreds of square miles of Kentucky at the opening of the present century.

There were scouts and runners threading their way through the trackless forests north and south of the Ohio, or coursing up and down the rivers, or spying out the actions of the war parties when they gathered near their villages and threw the tomahawk, daubed their faces with paint, and danced the war dance. These intrepid runners kept the frontier well informed of any formidable movements contemplated by the red men, so that no effective demonstration against the whites was feared.

Weeks and months passed, during which Ned Preston was not permitted to cross the intervening space between the block-house and the settlement, for the runners who came in reported great danger in doing so. Then again it looked almost as if the dawn of peace had come, and men were not afraid to move to and fro many furlongs distant from their homes.

Nearly twenty years had passed since the great pioneer, Daniel Boone, had explored a portion of the wonderful territory, and the numerous scenes of violence that had taken place on its soil made the name of the Dark and Bloody Ground characteristic and well-merited.

The several military expeditions which the Government had sent into the West had either been overwhelmingly defeated by the combined forces of Indians, or had accomplished nothing toward subduing the red men. The decisive campaign was yet to come.

But without dwelling on this portion of our story, we may say that in the autumn of 1788 comparative peace reigned over the portion of Kentucky of which we are speaking. When, therefore, the letters came down the Ohio in a flat-boat for Colonel Hugh Preston and several of those with him, and Ned asked permission to take them to his uncle, there was scarcely any hesitation in giving consent.

With this explanation the reader will understand how it came about that Ned and Blossom were in the depths of the Kentucky forest when the autumn day was closing, and while fully a dozen miles remained to pass before they could reach the block-house.

They had made a later start than usual from home, and rather singularly, although they had passed over the route so many times, they went astray, and lost several hours from that cause.

Soon after their departure from the settlement a friendly Shawanoe visited the place and warned the pioneers that trouble was coming, and it was wise to take more than usual precautions against surprise. When this Indian runner added that he was quite sure an assault was intended on the block-house, it can be understood that the parents of Ned were extremely alarmed for the safety of himself and Blossom.

If they should get through the stretch of forest to the block-house, their danger would not be removed; for an attack on that post was contemplated, and knowing its precise defensive power, as the Indians did, they would be likely to render the battle decisive.

"I hope the boys will reach the Colonel," said the father of Ned to his wife, "for they will have a chance to make a good fight for themselves."

"But the Colonel may know nothing of the attack intended, and he and the rest will be taken by surprise."

This doubt so disturbed the husband that he hurriedly sought the Shawanoe, who was still in the settlement, and asked him whether Colonel Preston had been apprised of the danger which threatened him. When informed that he had not, Mr. Preston insisted that Deerfoot, as the young Shawanoe was called, should make his way to the block-house without delay. The Indian, known to be one of the fleetest of warriors, said that he was on the eve of starting on that errand, and he left at once.

Before going, he was told that the two boys were threading their way through the forest toward the station, and the anxious father asked him to bring the lads back, if he deemed it the safer course. Ned was a great favorite with the Shawanoe youth, and the latter promised to use every effort to befriend him.

The question left to Deerfoot was whether it was his duty to hasten forward and apprise Colonel Preston of the peril impending over the garrison, or whether it would be safe to let him wait until the lads were conducted back to Wild Oaks. Deerfoot was disposed to hurry to the Licking; but when a few miles from the settlement he struck the trail of the lads, which he followed with as much ease as the bloodhound would have displayed under similar circumstances.

As both parties had started in the same direction, the prospect was that a junction would speedily take place, and the three could make the rest of the journey together; but before long Deerfoot was surprised to discover that Ned and Blossom had strayed from the true course. He could not understand why this happened, and his misgiving for Ned, whom he liked so well, led him to resolve to follow up the boy, and find out the cause.

Deerfoot was pushing forward on his loping trot, which he was able to maintain hour after hour without fatigue, when his wonderful instinct or reason told him he was in the vicinity of a large war party of Wyandots, the natural allies of his own tribe in their wars upon the settlements.

His belief was that the boys had been captured by them, in which event little hope remained; but it required no special maneuvering on his part to learn that his fears were baseless. The trail of the lads made an abrupt turn, showing that Ned Preston had suddenly "located" himself, and had returned to the right course. Although the footprints of the Wyandots actually approached within a hundred yards of those of the boys, yet singularly enough they came no nearer, and diverged from that point; so that, in all probability, the war party never suspected how close they were to the prize that would have been so welcome to them.

Accustomed as Deerfoot was to all species of danger in the woods, his dusky face flushed when he looked to the ground and saw how narrowly the boys had missed a frightful fate.

Such being the case, it became the duty of the Shawanoe to acquaint himself with the purpose of the Wyandot party. He therefore went directly among them to make his inquiries. This was a delicate and dangerous proceeding, for although the subtle Indian had done his utmost to keep secret from his own people his friendship and services for the whites (inasmuch as such a knowledge on the part of his race would have ended his usefulness and life), he knew well enough that his double-dealing must become known sooner or later to the Indians, and for a year or more he had never appeared among his people without misgiving as to the result.

All the wonderful cunning of his nature was brought into play when he advanced to meet the Wyandots, who were in their war-paint. He saw there were twenty-three, and that they numbered the bravest and most daring of their tribe. The leader was the chief Waughtauk, a fierce foe of the whites, whose tomahawk and scalping-knife had been reddened with innocent blood many a time.

Deerfoot was received with every appearance of cordiality by the chief and his men, for all knew what a splendid warrior the young Shawanoe was, and some of them had witnessed the extraordinary speed which had saved his life more than once.

It is as easy for the American to play a part as for the Caucasian, and Deerfoot was not entirely satisfied. He kept his wits about him, and used extreme care in not placing himself at any disadvantage which it was possible to avoid; but all the friendship seemed genuine, and when Waughtauk told him it was his intention to attack the exposed cabins of the settlers, Deerfoot believed him. When he added that he meant also to take a survey of the settlements along the Ohio, with the object of seeing which offered the most favorable opening for a sudden assault by a large war party, the Shawanoe was quite certain he spoke the truth.

Deerfoot then asked why they did not assail the block-house on the Licking, whose exposed situation seemed to invite such attack. Waughtauk answered that Colonel Preston had proved a good friend to the Indians who visited him, and it was decided to spare him.

This answer excited the suspicion of the youthful Shawanoe that the Wyandot chieftain had been deceiving him from the first; but Deerfoot was too cunning to reveal anything of his thoughts. When he bade his friends good-by, they at least were misled into the belief that he held no suspicion of the "double tongue" with which they had spoken.

It was no difficult matter for Deerfoot, when fairly away from the Wyandots, to shadow them until he learned whether they had falsified or not.

They kept to the northward several miles, until they had every reason to believe a long distance separated them from the Shawanoe, when they changed to the left, turning again a short distance further on, until their faces were directly toward Fort Bridgman, the block-house on the Licking.

That settled the question beyond dispute; they had told untruths to Deerfoot, and their purpose was to descend upon the station defended by Colonel Preston and only three able-bodied men.

After this discovery, the Shawanoe stood a moment leaning thoughtfully on his bow; an important truth impressed him:

"They suspect that Deerfoot is a friend of the white man, and therefore an enemy of his own race," was the thought of the Indian, who realized the fearful meaning to him of such a suspicion.

CHAPTER III.

OLD FRIENDS.

The discharge of the second arrow over the head and shoulders of Ned Preston and Wildblossom Brown lent wings to their flight; instead of coming to a standstill, as they did a short time before, they bent all their energies to escape, and ran with the utmost speed.

In such an effort the advantage was on the side of Ned as compared with the negro, for he was much more fleet of foot, and, as a consequence, within two or three minutes he was almost beyond sight.

"Hold on dar!" shouted Blossom; "dat aint de fair ting to leave a chap dat way."

Ned Preston could not desert the lad in this fashion, though it would not help him to stay behind and share his fate.

But his own disposition and the training received from his father led him to reproach himself for leaving him even for so short a time. He therefore stopped, and called back—

"Hurry, Blossom; every minute counts."

"Dat's jes' what I am a doin'," panted Blossom, struggling forward; "but I never could run as well as you——"

At that moment Ned Preston, who was looking toward the African, caught sight of an Indian close behind him. The warrior was in close pursuit, though the intervening vegetation for the moment prevented the young pioneer from seeing him distinctly. Enough was visible, however, to make his aim sure, and Ned brought his rifle to his shoulder.

"I hear de Injines! Dey're right behind me!" shouted the terrified Blossom; "get 'em in range, Ned, and shoot 'em all!"

Such a performance as this was out of the question, as a matter of course, but the boy was determined to do his utmost to help his friend.

When Ned raised his gun there was but the single warrior visible, and the sight of him was indistinct; but it was enough to make the aim certain, and the youth felt that one red man was certain to pay for his vindictiveness. At the same time he wondered why no others were seen.

But at the very moment the finger of Ned was pressing the trigger, the Indian disappeared as suddenly as if he had dropped through the mouth of a cavern. The target at which the gun was aimed had vanished.

Mystified and astounded, Ned Preston lowered his piece and stared at the point where the red man was last seen, as if he doubted his own senses. At the same moment a suppressed whoop was heard, and the warrior stepped to view from behind the sycamore, where he had leaped to dodge the bullet of the rifle which he saw aimed at him.

Ned was in the act of raising his gun again, when he almost let it fall from his grasp, with the exclamation—

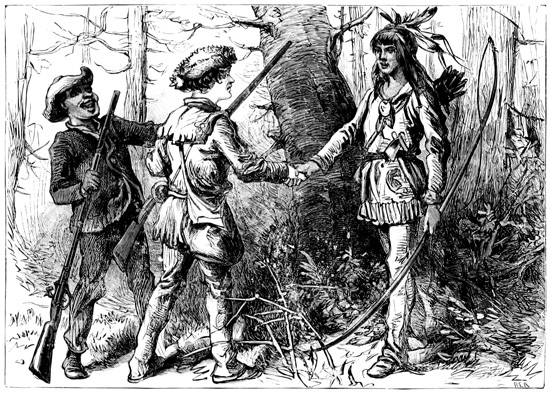

"Deerfoot!"

As the single word fell from his lips, his eyes rested on the figure of a young Indian of singular grace and beauty, who, without regarding the bewildered Blossom, walked forward to greet Ned Preston.

The Meeting with Deerfoot.

Deerfoot the Shawanoe, at the most, was no more than a year older than young Preston. He was about the same height, but of lighter mould, and with a length of lower limbs and a suppleness of frame which betokened great natural abilities as a runner: when we add that these capabilities had been cultivated to the highest point, it will not seem unreasonable that Deerfoot's unequalled swiftness of foot was known to several tribes besides his own.

Although a Shawanoe by birth (which tribe at that day had their hunting-grounds north of the Ohio), Deerfoot roamed through the forests south, and the exploits of the youth in running were told in the lodges by the camp-fires of the Shawanoe, the Wyandot, the Miami, the Delaware, and the Cherokee.

His expertness with the bow and arrow, his bravery in battle, his skill on the hunt, the fact that his mother was shot by settlers, and his father was killed in the famous Crawford expedition, caused Deerfoot to be formally ranked as a warrior when he was only fourteen years of age.

His deftness with his primitive weapons was no less remarkable than his fleetness of foot. Had he been living to-day, he would have taken the prize at the annual archery tournaments, even though he used a hickory bow instead of the double-backed yew or lancewood, and his missiles were made of the former material, with a single feather instead of the three, and were tied instead of being glued in place.

The bow and arrows of Deerfoot would have made a sorry show among those of the fair ladies and graceful gentlemen at the archery contests in these times; but those same shafts of the dusky American, with the keen flint or iron heads, had been driven by him with such prodigious force that they had found the heart of the deer or bear or bison at scarcely less than a hundred yards.

Deerfoot therefore refused to use the rifle, but clung to the bow, whose use he began studying when he was less than three years old.

As we have said, the young Shawanoe, now no more than seventeen years of age, was graceful of figure, with elastic, supple limbs, and with a perfect symmetry of frame. When he smiled, which happened now and then, he disclosed two rows of teeth as white, even, and beautiful, and free from decay, as ever existed. The nose was slightly aquiline, the eyes as black and piercing as those of a serpent, the forehead high, the cheek bones slightly prominent, the whole expression pervaded by that slight tinge of melancholy which seems to be the characteristic of the American race.

Deerfoot's costume and dress were those of the defiant warrior, who was the implacable foe of the white man. His hair, as long, black and coarse as that of a horse's mane, was gathered in a knot or scalp-lock on the crown, where it was tied and ornamented with eagle feathers, that were stained several brilliant hues; his hunting-shirt encased his sinewy arms, chest and waist, the ornamented skirt descending to his knees. The whole garment, made of buckskin obtained from the traders, was of a yellow color, the fringe being a deep crimson. Deerfoot shared the love of his people for flaring colors, as was shown by his handsomely decorated moccasins which encased his shapely feet, the various-hued fringes of his leggings, the string of bright beads around his neck, and the golden bracelet that he wore on his left wrist.

The red leathern belt, which clasped the waist of the young Shawanoe, formed a pretty contrast to the pale yellow of the hunting-shirt, and, a short distance off, would have been taken for the crimson sash worn by the civilized officer of modern times.

Behind this belt were thrust a tomahawk and hunting-knife, both keen of edge and terribly effective in the hands of the owner. The bundle of arrows was supported by a string passing around the neck, the missiles themselves resting behind the shoulder, the feathered points plainly seen by any one as they projected upward in front. In this place they were so accessible that Deerfoot, in discharging them at a foe or an animal, would have two or three in the air at the same time, there being what might be called a procession of arrows from the bow to the target, whatever it might be.

In the coldest weather, the youthful warrior gathered a heavy blanket about his shoulders, which hid all his figure, from his chin down to his twinkling moccasins. During the sultry season he occasionally threw off his hunting-shirt, except the skirt, so that arm, chest and neck were covered only by the rude figures which the mother had tattooed there by a most painful process during the days when Pa-wa-oo-pa, or Deerfoot, was a stoical papoose, tied to a flat piece of bark, and swinging in the tree branches, or lying motionless on the ground with limbs tied, and calmly watching the torturing operation with the bravery which is a part of the nature of the dusky hunters of the forest.

The bow of Deerfoot was of seasoned hickory, the string was dried sinew, and the weapon itself was all of six feet in length; so that, in discharging it, he did not hold it perpendicular, as is the rule, but in a slanting position; in short, the young Shawanoe violated more than one fundamental regulation in archery, but the fact remained that he could spit the gray squirrel on the top of the tallest oak; he could bring down the buck when leaping through the air; he had driven his sharp-pointed shaft through the shaggy body of the bison, and had brought the eagle flapping and dying to the ground when circling in the clear air far above his head.

Two years before, Deerfoot was the most vindictive enemy of the pioneers, who had slain both his father and mother. While attacking some settlers' cabins near Maysville, with nearly a score of other Shawanoes, they were surprised and almost annihilated by a party of whites led by Macaiah Preston, father of Ned. Deerfoot was wounded and taken captive. He fought like a young tiger, and the settlers, who knew his extraordinary skill and the injury he had done them, insisted on putting him to death.

But Macaiah Preston interposed, and would not permit it. He took him to his own home, and carefully nursed him back to rugged health and strength.

On the part of the good Samaritan he was assisted by his wife and Ned, who formed a strong attachment for the captive Shawanoe. The young brave more than reciprocated this friendship, the sentiment of gratitude being the most characteristic trait in his nature. He became henceforth the unfaltering ally and friend of the white race; from the bitterest enemy he was transformed into the most devoted friend, his fervency, like that of Saul of Tarsus, being as extreme as was his previous hatred.

The better to aid the settlers, Deerfoot returned to his own people, and kept up the semblance of enmity toward the pioneers. He even took part in several expeditions against them, but all proved disastrous failures to the assailants, and the youth did most effective service for those whom he had fought so fiercely a short time before.

It was of the utmost importance to Deerfoot that his true sentiments and real doings should be concealed from his people; for whenever the truth should become known to them, the most frightful death that could be conceived would be visited upon him.

The daring warrior believed his secret must be discovered; he believed he would fall a victim to their terrible vengeance sooner or later; but he was none the less faithful to the settlers. He simply resolved that he would never submit tamely to his fate; but, if the aborigines secured him for torment, it would be done by superior daring and subtlety.

Thus it was that the youthful Shawanoe was playing a most perilous and dangerous part; but he had played it so well that not until to-day had he seen just cause to believe any suspicion was afloat concerning himself.

The action of the Wyandots indicated that they preferred not to trust him with their secret. It was the first time anything of the kind had occurred, and it could not but cause uneasiness in the mind of Deerfoot.

It did not affect in the least, however, his course of action. He had set out to befriend Ned Preston and Wildblossom Brown, and it was his purpose to apprise Colonel Preston at Fort Bridgman of the danger to which his block-house was exposed.

"Deerfoot!" exclaimed Ned Preston, stepping hastily toward him and extending his hand; "I never was more glad to see you in all my life."

The handsome mouth of the Shawanoe expanded just enough to show the white teeth between the dusky lips, and he took the hand of Ned and pressed it warmly, immediately allowing the palm to drop from his own.

Then, without speaking, he turned toward Blossom, who, having seen how matters stood, was scrambling rapidly forward to greet the young warrior, whom he knew so well, and who was the most valuable companion they could have at such a time.

Deerfoot was left-handed by birth, but he had trained himself until he was ambidextrous, and he could draw the bow, hurl the tomahawk or wield the scalping-knife with the right as well as with the left hand.

In no single respect, perhaps, was his mental power more clearly shown than in the celerity with which he acquired the English language. When several years younger he was able to hold a conversation with the traders; and during the short time he remained with Macaiah Preston, before "escaping" to his people again, he became so proficient that he could readily act as interpreter.

"War dat you dat fired dat arrer at us?" demanded Wildblossom, as he caught the hand of Deerfoot, who nodded his head, with just a shadowy smile.

The American Indian, as a rule, does not like the African race, and he often shows an unreasonable prejudice against him. There seemed to be such a distaste on the part of Deerfoot, but he concealed it so well that Blossom Brown never suspected its existence. He treated the negro lad kindly because he belonged to the Prestons, whom the Shawanoe loved above all others.

"I thought you war a better shot dan to miss us," added Blossom, with the purpose of teasing their dusky friend; "your arrer neber teched me nor Ned."

"Did it hit the buck?" asked Deerfoot, smiling a little more decisively.

"Dat war 'cause you war so close to him."

"Deerfoot stood further away than did his white brother, who harmed him not with his gun."

"That was because my rifle missed fire," Ned hastened to explain; "if it was not for that, the buck would have fallen in his tracks."

"This gun never misses fire," said the Shawanoe, holding up the bow with no little pride.

"But it misses folks dat it am p'inted at," remarked Blossom, reaching out and giving Deerfoot a nudge in the back.

"Will my brother with the face of the night, walk a long ways in the wood and let Deerfoot send a single arrow toward him?"

There was a gleam in the dark eye of the young Shawanoe as he made this request, and no doubt it would have proven a dangerous challenge for Blossom to accept. The negro himself did not notice the full significance of the question, but Ned Preston did, and he trembled over the temerity of Blossom, who believed that Deerfoot felt as strong friendship for him as he himself felt for the matchless young warrior.

Unsuspicious of the slumbering storm, the African lad fortunately took the very best course to avert it. Shaking his head with a laugh, he said:

"Dar aint no better rifle-shots dan masser Ned dar; and I'd radder stand up afore him a hundred yards off, and let him draw bead on me, dan hab Deerfoot send one ob dem arrers whizzin' arter dis chile."

CHAPTER IV.

THROUGH THE TRACKLESS FOREST—THE CAUSE.

The compliment to the young Shawanoe, although rudely expressed, was genuine, and at once dissipated the latent lightning that was on the point of bursting forth.

The lowering eclipse that overspread the dusky countenance instantly cleared away, and Deerfoot smiled more than before as he turned toward Ned Preston to see how he accepted the remark of his servant.

The young pioneer was pleased, and, slapping the lad on the shoulder, exclaimed heartily—

"You show your good sense there, Blossom; and after this, when I hear the folks say you are the stupidest boy in all Kentucky, I will quote what you have just said to prove they are mistaken."

Wildblossom raised his cap and scratched his head, somewhat doubtful as to how he should accept this remark. While he was considering the matter, Deerfoot and Ned faced each other, and talked concerning more important matters.

The sun, which had been scarcely visible during the day, was now below the horizon, and the shadows of night were creeping through the autumn woods. The air continued chilly, and moaned among the branches, from which the crisp leaves, turning from bright yellow and flaming crimson to dull brown, were continually drifting downward. The squirrels whisked from limb to limb, gathering their winter store of nuts, and chattering their defiance from the highest branches of elm, oak, ash, hickory, chestnut, or maple.

Now and then feathery particles of snow whirled around them, so light and downy that they scarcely found their way to the leaves below. It was the time of the sad and melancholy days, though the most joyous one to the hunter.

Ned Preston had been told by Deerfoot that he was the only Indian near them, and he was vastly relieved that the danger was found to be scarcely any danger at all.

As it was becoming colder, and night was closing in, the boy was anxious to go into camp. He could conceive of no reason why they should push forward any further before morning, as he held no suspicion of the critical condition of affairs.

But he quickly learned the truth from Deerfoot, who related, in his pointed way, the story of the Wyandots under the fierce war chief Waughtauk.

"And they are going to the block-house!" exclaimed the astonished lad.

The young warrior nodded his head to signify there could be no doubt of the fact.

"Then we had better turn around and go back to Wild Oaks as quickly as we can."

"Deerfoot must hurry to Colonel Preston and tell him of the Wyandots," said the Shawanoe; "that is Deerfoot's first duty."

"Of course; I didn't expect you to go with us; we can make our way home without help."

"But your feet wandered from the path only a few hours ago."

"We were careless, for we felt there was no need of haste," replied young Preston; "that could not happen again, when we know such a mistake might work us ill."

"But that was in the daytime; it is now night."

Ned felt the force of this fact, but he would not have hesitated to start on the back trail without a minute's delay.

"When we found we were going wrong we could stop and wait till the rising of the morning sun. I have several letters which you can deliver to my uncle."

Deerfoot shook his head; he had another course in mind.

"We will go to the fort; you will hand the letters to the white soldier; Deerfoot will show the way."

"Deerfoot knows best; we will follow in his footsteps."

The Shawanoe was pleased with the readiness of the young pioneer, who, it must be stated, could not see the wisdom of the decision of their guide.

If Waughtauk and his warriors were in the immediate vicinity of the block-house, the boys must run great risk in an attempt to enter the post. They could not reach the station ahead of the Wyandots, and it would be a task of extreme difficulty to open communication with Colonel Preston, even though he knew the loyalty of the dusky ally of the whites.

Deerfoot would have a much better prospect of success alone than if embarrassed by two companions, whom the other Indians would consider in the light of the very game for which they were hunting.

It seemed to Ned that it would be far more prudent for the young Shawanoe to take the letters and make his way through the trackless forest, while Ned and Blossom spared no time or effort in returning to Wild Oaks.

But the matchless subtlety and skill of Deerfoot were appreciated by no one more than by young Preston, who unhesitatingly placed himself under his charge.

But cheerfully as the wishes of the Shawanoe were acceded to by the white boy, the African lad was anything but satisfied. Of a sluggish temperament, he disliked severe exertion. He had not only been on the tramp most of the day, but, during the last half hour, had been forced to an exertion which had tired him out; he therefore objected to a tramp that was likely to take the better portion of the night.

"We'd better start a fire here," said he, "and den in de mornin' we'll be fresh, and we can run all de way to de Lickin', and get dar 'bout as soon as if we trabel all night and got tired most to def."

The Shawanoe turned upon him in the dusky twilight, and said—

"My brother with the face of the night may wait here; Deerfoot and his friend will go on alone."

With which decisive remark he wheeled about, and, facing southwest, strode off toward the block-house on the Licking.

"Wildblossom aint gwine to stay here, not if he knows hisself, while you folks go to your destruction," exclaimed the servant, falling into line.

The strange procession was under way at once. Deerfoot, as a matter of course, took the lead, Ned Preston stepping close behind him, while the African kept so near his young master that he trod on his heels more than once.

The Shawnee displayed his marvellous woodcraft from the first. Although the ground was thickly strewn with leaves, his soft moccasins touched them as lightly as do the velvet paws of the tiger when stealing through the jungle. Ned Preston took extreme care to imitate him, and partially succeeded, but the large shoes of Blossom Brown rumpled and tumbled the dry vegetation despite every effort to avoid it.

It was not until reproved by Ned, and the gait was slackened, that, to a certain extent, the noisy rustling was stopped.

There were no stars nor moon in the sky, there was no beaten path to follow, and they were not on the bank nor along the watercourse of any stream to guide them; but the dusky leader advanced as unerringly as does the bloodhound when trailing the panting fugitive through the marshy swamps and lowlands.

As the night deepened, Ned saw only dimly the figure of the lithe and graceful young warrior in front. His shoulders were thrown forward, and his head projected slightly beyond. This was his attitude while on the trail, and when all his faculties were alert. Eye and ear were strained to the highest tension, and the faint cry of a bird or the flitting of a shadowy figure among the forest arches would have been detected on the instant.

Ned Preston could catch the outlines of the scalp-lock and eagle feathers, which took on a slightly waving motion in response to the long, loping tread of the Indian; occasionally he could detect a part of the quiver, fastened back of the shoulder, and the upper portion of the long bow, which he carried unstrung in his right hand.

Then there were moments when the guide was absolutely invisible, and he moved with such silence that Ned feared he had left them altogether. But he was there all the time, and the journey through the desolate woods continued with scarcely an interruption.

Suddenly Deerfoot came to a halt, giving utterance at the same moment to a sibilant sound as a warning to Ned Preston, who checked himself with his chin almost upon the arrow-quiver. It was different with Blossom, who bumped his nose against the shoulders of his young master with such violence that Ned put up his hand to check himself from knocking the guide off his feet.

Neither Ned nor Blossom had caught the slightest sound, and they wondered what it was that had alarmed Deerfoot.

No one spoke, but all stood as motionless as the tree trunks beside them, those behind waiting the pleasure of him who was conducting them on this dangerous journey.

For fully five minutes (which seemed doubly that length) the tableau lasted, during which the listening followers heard only the soughing of the night-wind and the hollow murmur of the great forest, which was like the voice of silence itself.

Then the faint rustle of the leaves beneath the moccasins of the Shawanoe showed that he was moving forward again, and the others resumed walking, with all the caution consistent with necessary speed.

Fully a half mile was passed in this manner, the three advancing like automata, with never a whisper or halt. Blossom, although wearied and displeased, appreciated the situation too well to express his feelings, or to attempt anything to which either of the others would object.

"Dey aint likely to keep dis up for more dan a week," was the thought which came to him; "and when I make up my mind to it, I can stand it as long as bofe of 'em together."

However, Blossom had almost reached the protesting point, when he heard the same warning hiss from the Shawanoe, and checked himself just in time to avoid a collision with his young master.

The cause of this stoppage was apparent to all: they stood on the bank of a creek a hundred yards wide, which it was necessary to cross to reach the block-house. It ran into the Licking a number of miles south, and so far below Fort Bridgman that there was no way of "going round" it to reach the station.

It was the custom of the boys, when making the journey between Wild Oaks and the block-house, to ferry themselves over on a raft which they had constructed, and which was used on their return. As they took a course each time which brought them to the same point on the tributary, this was an easy matter. During the summer they sometimes doffed their garments, and placing them and their guns on a small float, swam over, pushing their property before them.

The water was too cold to admit of any such course now, unless driven to it by necessity; and as Deerfoot had brought them to a point on the bank far removed from the usual ferrying place, Ned concluded they were in an unpleasant predicament, to say the least.

"How are we going to get across?" he asked, when they had stood motionless several minutes looking down on the dim current flowing at their feet.

"The creek is not wide; we can swim to the other shore."

"There is no doubt of that, for I have done it more than once; but there is snow flying in the air, and it isn't a favorite season with me to go in bathing."

A slight exclamation escaped the Shawanoe, which was probably meant as an expression of contempt for the effeminacy of his white friend.

Be that as it may, he said nothing, nor did he, in point of fact, mean to force the two to such a disagreeable experience.

"Wait till Deerfoot comes back."

As he uttered these words he moved down the bank, while Blossom Brown threw himself on the ground, muttering—

"I would like to wait here all night, and I hope he has gone for some wood to kindle a fire."

"There is no likelihood of that," explained Ned, "for he is too anxious to reach the block-house."

"I tink he is anxiouser dan——See dat!"

At that moment the dip of a paddle was heard, and the lads caught the faint outlines of a canoe stealing along the stream close to the shore. In it was seated a single warrior, who did not sway his body in the least as he dipped the paddle first on one side the frail boat and then on the other.

"He's arter us!" whispered Blossom, cocking his rifle.

"Of course he is; it's Deerfoot."

"I forgot all about dat," said the lad, lowering his piece, with no little chagrin.

Ned Preston now cautiously descended the bank, followed by Blossom, and while the Shawanoe held the craft against the shore, they stepped within, Ned placing himself in the bow, while his companion took a seat at the stern.

Then, while Deerfoot deftly poised himself in the middle, he lightly dipped the ashen paddle alternately on the right and left, sending the canoe forward as gracefully as a swallow.

"Whose boat is that?" asked Ned.

"It belongs to some Pottawatomie," answered the Shawanoe, speaking with a confidence which showed he held no doubt in the matter, though he might have found it hard to tell his companions the precise means by which he gained the information.

Deerfoot, instead of speeding directly across, headed south, as though he meant to follow the stream to its confluence with the Licking. Suspecting he was not aware of his mistake, Blossom deemed it his duty to remind him of it.

"You are gwine de wrong way, if you did but know it, Deerfoot; de oder side am ober dar."

Perhaps the young Shawanoe indulged in a quiet smile; if so, he made no other sign, but continued down the creek with arrowy swiftness for two or three hundred yards, when he began verging toward the other shore.

Ned Preston made no remark, but alternately peered ahead to discern where they were going, and back, that he might admire the grace and skill with which the Indian propelled the light structure.

All at once, with a sweep of the paddle, the boat was whirled around with such suddenness that Blossom Brown thought they were going to upset and be precipitated into the water. By the time he recovered himself the delicate prow touched the shore as lightly as if drawn by a lady's hand.

Ned instantly stepped out, the others doing the same. When everything was removed, Deerfoot stooped over, and, without any apparent effort, raised the canoe from the water.

"I s'pose he am gwine to take dat along to hold ober our heads when it rains."

But Blossom was altogether wide of the mark in his theory. The Shawanoe carried it only a few paces, when he placed it under a clump of bushes, pulled some leaves over it, laying the paddle beneath, and then once more turned to resume their journey.

CHAPTER V.

"SHUT OUT."

Deerfoot informed his friends that they were now within seven miles of the block-house. Although the night was far advanced, he expected to reach their destination long before morning. At that season the days were short, and as the Shawanoe was familiar with the woods, and could travel with as much certainty in the darkness as the light, there was no delay counted upon, unless they should approach the vicinity of some of the Wyandots.

The order of march was taken up precisely as before, Deerfoot warning the others to walk with the least noise possible, he setting the example by advancing absolutely without any sound that could betray his footsteps.

Ned Preston felt the touch of a few wandering snowflakes against his cheek, but there were not enough to show themselves on the leaves. The exercise of walking and their thick garments kept them sufficiently warm, though it would have been different had they been in camp. In the latter case, as they had no encumbering blankets, it would have gone ill without a roaring camp-fire.

The journey now became monotonous, even to young Preston, who found it tiresome to walk so continuously without the least noise or occurrence to awaken alarm. They must have gone at least four miles in this manner, Blossom plodding along with a certain dogged resolution which kept him close on the heels of his young master.

The latter often felt like protesting, but nothing could have persuaded him to do so. It would have offended Deerfoot, who was the guide of the party, and who was directing affairs in accordance with his own theory of strategy. He knew that that scout is sure to meet disaster, sooner or later, who allows his impatience to influence his judgment, and who fails to use the most extreme caution whenever and wherever there is the shadow of danger.

When Preston began to believe they were in the vicinity of the Licking, Deerfoot came to an abrupt and noiseless halt. This time he spoke the single word—

"Listen!"

The two did as requested, but were unable to detect anything beside the hollow moaning of the wind through the trees, and the faint, almost inaudible murmur of the distant Licking. Several minutes passed, and then the guide asked—

"Do my brothers hear anything?"

They answered that they could distinguish nothing more than was always to be heard at such times.

"We are close to the camp of the Wyandots," was the alarming information.

"How do you know that?" inquired his friend.

"Deerfoot heard them," was the explanation, in such a guarded undertone that his companions barely caught his words.

No one thought of doubting the assertion of the Indian, incredible as it sounded, and the truth of his declaration was soon manifest. Certain as he was that they were close to a party of his own race, the advance was made with greater care than before.

He picked his way with such patience and slowness that Blossom found plenty of time in which to lift his feet as high as he knew how, setting them down as though afraid of waking a slumbering baby near at hand.

Within two rods of the spot where they halted they suddenly caught the starlike twinkle of a point of fire directly ahead. Instantly all stopped, and no one spoke; they knew that it was the camp-fire of the party whose presence the Shawanoe learned a few minutes before.

Nothing more than the glimmer of the light could be seen, because there were so many trees and so much vegetation intervening.

"Let my brothers wait till I return," said Deerfoot, turning his head so as not to speak too loud.

"It shall be done," replied Ned Preston, who was on the point of asking a question, when he became aware that he and Blossom were alone: Deerfoot had vanished with the silence of a shadow.

"If we've to wait yar a long time," said Blossom in a husky whisper, "we might as well sot down."

Preston made no objection to this on the part of his servant, but he remained standing himself, leaning against a tree, while Blossom supported his head in the same way.

"I don't care if Deerfoot doesn't come back for a week," remarked the negro lad, with a sigh of contentment that at last he was permitted to rest his limbs.

"He will not stay long," said Ned; "and the best thing we can do while he is away is to do nothing."

"Dat's just what I'm doin' as hard as I can."

"I wouldn't even speak, Blossom, for some of the Indians may be near us."

"Dat suits me jes' as well," assented the other, who thereafter held his peace.

Meanwhile, Deerfoot the Shawanoe approached the camp-fire of the Indians with all the care and skill he could command. Possibly he would have incurred no great risk by stalking boldly forward, for he was already known among the tribe, which was an ally of the Shawanoes.

But the incident of the afternoon had taught him a lesson, and he knew such a course would deepen the suspicion which some of the Wyandots already held against him.

They had given him to understand they were on their way to reconnoiter Wild Oaks and some of the settlements along the Ohio. If they should find he was dogging them, what other proof could they ask that he was playing the part of spy and enemy?

For this reason the Shawanoe determined to avoid observation, and to make his reconnoissance precisely as though he were an avowed foe of those of his own race.

He had not gone far when he gained a full view of the camp. That which immediately caught his attention and increased his misgiving was the fact that this was a new party altogether. Waughtauk did not lead these warriors, none of whom was with the company whom the young scout encountered during the afternoon.

But several other important facts were significant: these were also Wyandots; they numbered thirteen, and they were in their war-paint. They had probably left their towns north of the Ohio at the same time with Waughtauk, and they had separated, the better to carry out some project the chief had in view.

Shrewd and sagacious beyond his years as was the Shawanoe, he was in a situation in which he was compelled to do no little guessing. He was satisfied that the chief and his warriors intended to compass the destruction of the block-house, sometimes known as Fort Bridgman, and to massacre every one within it.

The Wyandots, like the Shawanoes, were brave fighters, and why they had not assailed the post was hard to tell, when it would seem they numbered enough to overwhelm the garrison. It looked as if Colonel Preston had discovered his danger, though it was not an uncommon thing for a war party to delay their attack on a station a long time after it seemed doomed beyond all hope.

The Wyandots had disposed themselves in a fashion that looked as though they meant to stay where they were through the night. They had evidently finished a meal on something, and were now smoking their pipes, lolling on their blankets, sharpening their knives with peculiar whetstones, cleaning their guns, now and then exchanging a few guttural words, the meaning of which not even the sharp-eared Shawanoe could catch.

"They mean to attack the block-house," was the conclusion of Deerfoot, who tarried only a few minutes, when he began a cautious return to his two friends, who were found as he had left them, except that Blossom Brown was on the verge of slumber.

Deerfoot quickly explained what he had learned, and added that the difficulty of entering the block-house was increased; but he believed, by acting promptly, it could be done with safety. Ned Preston was inclined to ask wherein the use lay of all three going thither, when one would do as well, and the obstacles were much greater than in the case of a single person.

But the course of the guide convinced Preston that he had some plan which he had not yet revealed, and which necessitated the entrance of the young pioneer at least into the block-house.

"Have you any knowledge when the Wyandots will attack Colonel Preston?"

"The break of day is a favorite hour with Deerfoot's people, but they often take other seasons."

"Why are they not closer to the station?"

"They are already close; we are within three hundred yards of the fort; Deerfoot will lead the way, and if the warriors' eyes are not like those of the owl, we may pass through the gate before the first sign of light in the east."

There was no necessity of telling Ned and Blossom that their caution must not be relaxed a single moment: no one could know better than they that the briefest forgetfulness was likely to prove fatal, for the Wyandots were all around them. The detection of either lad would seal his fate.

The purpose of Deerfoot was to steal nigh enough to the block-house to apprise the inmates that they were on the outside, and awaiting an opportunity to enter. Could they succeed in letting Colonel Preston know the truth, all three could be admitted in the darkness, with little danger to themselves or to the garrison.

What the Shawanoe feared was that the Wyandots had established a cordon, as it might be termed, around the block-house. It was more than probable that Colonel Preston had discovered the approach of the hostiles in time to make quite thorough preparations.

While this might not avert the attack of the red men, it was certain to delay it. The next most natural proceeding for the commandant would be to dispatch a messenger to Wild Oaks, to inform the settlers of his peril, and to bring back help. The assailing Indians would anticipate such a movement by surrounding the block-house so closely that the most skillful ranger would find it impossible to make his way through the lines.

If such were the case, it followed as a corollary that no friend of the garrison would be able to steal through the cordon and secure entrance into the building: the gauntlet, in the latter case, would be more difficult than in the former, inasmuch as it would be necessary first to open communication with Colonel Preston, and to establish a perfect understanding before the task could be attempted.