The Ranger Or, The Fugitives of the Border

Edward S. Ellis

THE RANGER

OR

THE FUGITIVES OF THE BORDER

BY EDWARD S. ELLIS

AUTHOR OF "OONOMOO," "SET JONES," "IRONA," ETC.

NEW YORK

HURST & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1911,

BY

HURST & COMPANY.

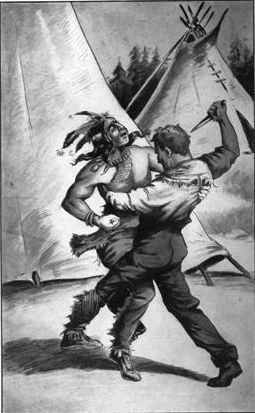

"Hold! You strike the white man's friend!"

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I. Zeb and his Master

CHAPTER II. The Night of Terror

CHAPTER III. Kent and Leslie

CHAPTER IV. The Captives

CHAPTER V. The Meeting on the River

CHAPTER VI. The Raft

CHAPTER VII. Lost and Found

CHAPTER VIII. The Companion in Captivity

CHAPTER IX. Zeb's Revenge

CHAPTER X. The Brief Reprieve

CHAPTER XI. A Friend

CHAPTER XII. Escape

CHAPTER XIII. The Captive

CHAPTER XIV. The Rescue

CHAPTER XV. The Fugitives Flying no Longer

BOY INVENTORS SERIES

BUNGALOW BOYS SERIES

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

"Hold! You strike the white man's friend!"

George and Rosalind

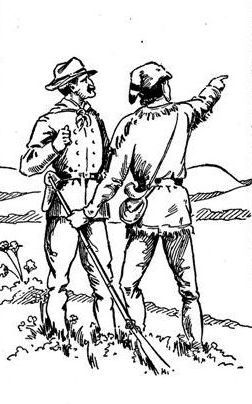

"Them varmints," said he, "are playing particular devil in these parts"

There were two horses in the party, and upon one of these Rosalind had been placed

"Ready," whispered Leslie, "you take the nearest one."

"You shoot Indian, eh?" said one, brandishing his knife at the same time

The savages were amusing themselves by ascertaining who could send his tomahawk nearest the body of their captive without touching him

"Does the maiden remember Pequanon?"

Two savages were left on shore

"Yonder is something approaching."

KENT, THE RANGER.

CHAPTER I.

ZEB AND HIS MASTER.

At the southern part of Ohio, where the river of that name swerves from its south-western course, and makes a sweeping bend toward the north-west, many years ago stood a large and imposing dwelling. Its character, so different and superior to others found here and there along the Ohio, showed that its owner must have been a man both of superior taste and abundant means. It had been built by Sir William Leland, who had emigrated from Europe with his young wife, and erected a home in the western wilderness. Here they lived a goodly number of days; and when, at last, they took their departure within a year of each other, they left behind them a son and daughter to cherish and inherit their home.

George Leland, at the time of which we speak, was but twenty, while his sister Rosalind was three years his junior. Yet both, with the assistance of a faithful negro servant, managed to live quite comfortably. The soil was exceedingly rich, and, with a little pains, yielded abundantly every thing that could be wished, while the river and wood were unfailing resources. Three years had elapsed since the elder Leland's death, and during that time, although living in a country swarming with Indians, nothing had occurred to alarm the fears of our friends, or even to give them the slightest suspicion that danger threatened them.

George and Rosalind.

When Sir William settled in this section, he followed the example of the great founder of Pennsylvania, and purchased every foot of his land from those who claimed it; and, in addition to the liberal remuneration which each received, they were given some charming present by their pale-faced brother. This secured their friendship; and, although many miles intervened between the whites and their nearest kindred, yet they had nothing to fear from the savages who surrounded them. Thus matters stood when George and Rosalind were left orphans, some years before the opening of our story.

It was a pleasant day in early summer that George and his sister were seated in front of their house. The sun was just setting, and they had remained thus a long time. Zeb, the negro, was absent for the time, and they were thus undisturbed.

"Do you really think," pursued the sister, "it can be true that the Indians have perpetrated the outrages which have been reported?"

"I should be glad to think differently, could I have reason for doing so; but these reports certainly have foundation; and what is more alarming, the suspicion that we are not safe, which was awakened some time ago, is now confirmed. For two or three days I have detected suspicious appearances, and Zeb informed me that he discovered a couple of savages lurking around the edge of the forest. I fear there is strong reason to apprehend danger."

"But, brother, will not the kindness which our parents showed them while living be a guaranty of our protection?"

"It may, to some extent; but you must remember that there are hundreds of Indians who have never seen or heard of them, who would not hesitate to kill or take us prisoners at the first opportunity."

"Can it be possible?"

"It is not only possible but true. You remember Roland Leslie, who was here last summer? Yesterday I saw him up the river, and he gave me the information that I have repeated. At first I deferred mentioning it to you, for the reason that I did not wish to alarm you until it could not be avoided."

"Why did he not come here?" asked the sister.

"He said that he should shortly visit us. He had heard rumors of another massacre some miles up the river, and wished to satisfy himself in regard to it before calling here. Leslie, although young, is an experienced hunter and backwoodsman, and I have not much fear for his personal safety. He assured me that, should he find the Indians above ravaging the country as fearfully as reported, he would immediately return to us."

"I hope so," earnestly replied Rosalind.

"Still," continued George, "what can we do, even then? He intends to bring a hunter back with him, and that will make only three of us against perhaps a thousand savages."

"But have we not the house to protect us?"

"And have they not the forest? Can they not lurk around until we die of hunger, or until they fire the building? There are a hundred contingencies that will bar an escape, while I confess no prospect of getting safely away presents itself."

"We have arms and ammunition," said Rosalind. "Of course Leslie and his friend are good marksmen, and why can we not do enough to deter and intimidate the savages? Finding us well prepared, they will doubtless retreat and not disturb us again. I hope the trouble will soon be over."

"I hope so too; but it is hoping against hope. This war will be a long and bloody one, and when it is over the country will present a different appearance. Many lives must be lost ere it is done, and perhaps ours are among that number."

"Perhaps so, brother; but do not be so depressed. Let us hope and pray for the best. It is not such a sad thing to die, and the country which has given us birth has certainly a strong claim upon us."

"Noble girl," exclaimed George, "it is so, and we have no cause for murmuring."

At this moment Zeb appeared. He was a short, dumpy, thick-set negro, with a most luxuriant head of wool, a portion of which hung around his head in small, close braids, resembling bits of decayed rope. His eyes were large and protruding, and his face glistened like a mirror. He was a genuine African. Some of their qualities in him were carried to the extreme. Instead of being a coward, as is often the case with his nation, he seemed never to know when there really was danger. He always was reckless and careless, and seemed to escape by accident.

"Heigh! massa George, what's up?" he exclaimed, observing the solemn appearance of the two before him.

"Nothing but what is known to you, Zeb. We were just speaking of the danger which you are aware is threatening us. Have you seen anything lately to excite suspicion?"

"Nothin' worth speakin' of," replied he, seating himself in front of George and Rosalind.

"What was it, Zeb?" asked the latter.

"When I's out tendin' to things, I t'ought as how I'd sit down and rest, and 'cordin'ly I squats on a big stone. Purty soon de stone begin to move, and come to look, 'twas a big Injin.

"'Heigh!' says I, 'what you doin' here?'

"'Ugh!' he grunted.

"'Yes, I'll "ugh!" you,' says I, 'if I cotches you here ag'in.' With dat I pitches him two, free rods off, and tells him to make tracks fur home."

"Heavens! if you would only tell the truth, Zeb. Did you really see an Indian, though?"

"'Deed I did, and he run when he see'd me in arnist."

"And you saw others yesterday, did you?" remarked Rosalind.

"Two or free, down toward de woods. I spied 'em crawlin' and smellin' down dar, and axes dem dar business. Dey said as how dey's lookin' for a jack-knife dat dey lost dar last summer. I told 'em dat dey oughter be 'shamed demselves to be smellin' round dat way; and to provide against dar doin's in future, I give dem each a good kick and sent dem away."

"Do not exaggerate your story so much," said Rosalind. "Give the truth and nothing else."

"Qua'r, folks won't believe all dis pusson observes," said he, with an offended air.

"Tell the truth and they will in all cases; but should you deceive once, you will always be suspected afterward."

"Dat's it," commenced the negro, spreading out his broad hand like an orator to illustrate the point. "If I tells de truf dey're sure to t'ink I's lyin', and what's de use?"

"Zeb," commenced George, not regarding the last remark, "you, as well as we, are aware that we are encompassed by peril. You have seen that the Indians are constantly prowling around, and evidently for no good purpose. What would you advise us to do under the circumstances?"

"Give 'em all a good floggin' and set 'em to work," he replied.

"Come, come, Zeb, we want no jesting," interrupted Rosalind.

"Dar 'tis ag'in. Who war jestin'? Dat's what I t'ink is de best. Give 'em a good lickin', and set 'em to work clearin' off de wood till dar spunk is gone."

"Fudge!" said George, impatiently, turning his back toward Zeb, whose head ducked down with a chuckle.

"Rosalind," said George, "the best plan is certainly to wait until Leslie returns, which will be either to-morrow or the next day. We will then determine upon what course to pursue. Perhaps we shall be undisturbed until that time. If not, it cannot be helped."

"Wished dis pusson warn't so hungry," remarked Zeb, picking up a stick and whittling it.

Rosalind smiled as she arose and remarked:

"It is getting late, George, and it perhaps is best to have supper."

He made no answer and turned toward the negro.

"Zeb," said he, "in all probability we shall be obliged to leave this place in a few days for a safer location. Of course you will accompany us, and I wish it to be understood that you are to lay aside this levity and carelessness. Remember that you are in danger, as much as ourselves. Your scalp may be the first taken."

"What, dis yere wool of mine? Yah! yah! yah! Lord bless you, dey'd have a handful!"

"How would you relish being roasted at the stake?" asked George, hoping to terrify him.

"Yah! yah! Dey'd be some sizzlin', I guess."

"You will think soberly about the matter, perhaps sooner than you suspect."

"Yas," said Zeb, and his face straightened out in an instant, while he slowly and thoughtfully continued whittling.

"Zeb," continued George, leaning toward him and speaking in an undertone, "I think we shall be attacked in two days at the latest."

"Jest keep de whip in good order, and I'll put it into 'em and teach 'em manners."

"I fear you will learn wisdom only by experience, even if you do then," returned George. "It would be a good thing for you, should you meet with something that would impress you with a sense of your peril. I can only wonder at your stupidity."

"Gorra mighty! do you s'pose dere's anything that'd make me afeard of dem Injins? Why, bless you, forty of 'em wouldn't dare to frow a stone at me. I've licked free, four dozen of 'em, and dey all respect me awful."

"I suppose so," rejoined young Leland, with mock seriousness.

"Last summer," pursued Zeb, "when you's down de river fishin', dere's thirteen of 'em come up one day to borrer de wood-box. I s'pose dey wanted to keep dar dogs and pappooses in it, and I 'cluded as how dey warn't gwine to get it. So I told 'em I's very sorry dat I couldn't 'commodate 'em, but de fact war we wanted to put de wood in it ourselves. When I said dat, one of de niggers begin to got sassy. I just informed 'em dat dey'd better make demselves scarce mighty quick, if dey didn't want dis pusson in dar wool. Dey didn't mind what was said, howsumever, and purty soon I cotched 'em runnin' off wid de wood-box. Dat raised my dander, and I grabbed de box and frowed it right over dar heads and cotched 'em fast. Den I put a big stone on it, and kept 'em dere free weeks, and afore I let 'em out I made 'em promise to behave 'emselves. Now I considers dat we'd better serve 'em some sich trick. Tie two, free hundred to de fence, and leave 'em dere for a few months."

"You are welcome to try it," returned George, rather disgusted at the negro's propensity for big story telling. He arose and passed within, where the ample table was laid. Yet he could not eat the plain, sweet food which Rosalind's own hands had prepared. The dreadful sense of danger was too real a guest for any rest or peace of mind.

CHAPTER II.

THE NIGHT OF TERROR.

Few words were interchanged during the evening. George and Rosalind had enough to occupy their minds, and Zeb, finding them taciturn, relapsed into a sullen silence.

At an early hour each retired. Rosalind now felt more than George that unaccountable presentiment which sometimes comes over one in cases of danger. During the last few hours it had increased until it nearly resolved itself into a certainty.

The view from the front of the house was clear and unobstructed to the river, a quarter of a mile distant. Along this lay the cultivated clearing, while the forest, stretching miles away, approached to within a few yards of the rear of the house.

Rosalind's room overlooked this wilderness. Instead of retiring, she seated herself by the window to gaze out upon it. There was a faint moon, and the tree-tops for a considerable distance could be seen swaying in the gentle night-wind. The silence was so profound that it seemed to make itself felt and, in that vast solitude, few indeed could remain without being impressed with the solemn grandeur of nature around.

Hour after hour wore away; still Rosalind remained at the window. As there was no inclination to sleep, she determined to remain in her position until morning. She knew that it must be far beyond midnight, and at the thought there sprung up a faint hope within her breast. But she was startled by the dismal hoot of an owl. She sprang up, with a beating heart, listening intently and painfully; but no other sound was heard. Trying to smile at her trepidation, she again seated herself and listened; in a moment that cry was repeated, now in an opposite direction from which the first note was heard.

Rosalind wondered that the simple circumstance should so affect her; but try as much as she might, she could not shake it off. Again, for a few minutes, she remained trembling with an undefinable fear, when there came another hoot, followed instantly by another, in an opposite direction. She began now to entertain a fearful suspicion.

Her first impulse was to awaken her brother, but, after a moment's thought, she concluded to wait a short time. A few more sounds were heard, when they entirely ceased. During this time, Rosalind, although suffering an intense fear, had been gazing vacantly toward the point or clearing nearest the house. As her eyes rested upon the spot, she caught the shadowy outlines of a dark body moving stealthily and noiselessly along upon the ground.

Without waiting a moment, she darted to George's room. He had not slept, and in an instant was by her side.

"Call Zeb," she exclaimed. "We are surrounded by Indians."

Leland disappeared, and in a moment came back with the negro.

"Gorra mighty!" said the latter, in a hurried, husky whisper, "where am de cussed niggers? Heigh, Miss Rosa?"

"Keep quiet," she replied, "or you will be heard."

"Dat's just what I wants to be, and I calkilates I'll be felt too, if dar are any of 'em 'bout."

"Stay here a moment," said George, "while I look out. Rosalind, what did you see?"

"A body approaching the house from the woods. Be careful and do not expose yourself, George."

He made no answer and entered her room, followed by herself and the negro, who remained at a safe distance, while he cautiously approached the window. He had no more than reached it, when Zeb asked:

"See noffin'?"

This question was repeated perhaps a dozen times without an answer, when the patience of Zeb becoming exhausted, he shuffled to the window and pressed his head forward, exclaiming:

"Gorra mighty, whar am dey?"

"Hist! there is one now—yes, two of them!"

"Whar—whar?"

"Keep your mouth shut," interrupted the young man, his vexation causing him to speak louder than he intended.

"Heigh! dat's him! Look out!"

And before young Leland suspected his intentions or could prevent it, Zeb had taken aim and fired. This was so sudden and unexpected that, for a moment, nothing was heard but the dull echo, rolling off over the forest and up the river. Then arose a piercing, agonized yell, that told how effectual was the shot of the negro. Rosalind's face blanched with terror as she heard the fearful chorus of enraged voices, and thought of the fearful scene that must follow.

"Are the doors secured?" she asked, laying her hand upon George's shoulder.

"Yes, I barricaded them all," he answered. "If they do not fire the building, we may be able to keep them off until morning. I don't know but what Zeb's shot was the best, after all—God save us!"

This last exclamation was caused by a bullet whizzing past, within an inch of his face. For a while Leland was uncertain of the proper course to pursue. Should he expose his person at the window, he was almost certain to be struck; yet this or some other one equally exposed, was the only place where he could exchange shots, and the savages must be kept in check.

Zeb had reloaded his gun, and peering around the edge of the window, caught a glimpse of an Indian. As reckless of danger as usual, he raised his rifle and discharged it. He was a good marksman, and the shot was as effective as the other.

"Gorra mighty!" he exclaimed, "I can dodge dar lead. Didn't I pick dat darkey off awful nice? Just wait till I load ag'n." Chuckling over his achievements, he proceeded to prime his rifle. George Leland withdrew to the window of another room, from which he succeeded in slaying a savage, and by being careful and cautious, he was able to make his few shots tell with effect.

When Zeb shot the first savage, the red-skins sprung to their feet and commenced yelling and leaping, feeling that those within were already at their mercy; but the succeeding shots convinced them of their mistake, and retreating to cover, they were more careful in exposing themselves. Several stole around to the front of the house, but George had anticipated them, and there being no means of concealing their appearance, they were easily kept at a distance. Rosalind followed and assisted him as far as lay in her power, while Zeb was left alone in his delight and glory.

"Be careful," said Leland; "don't come too near. Just have the powder and wadding ready and hand it to me when I need it."

"I will," she replied, in a calm, unexcited voice, as she reached him his rod.

"Just see what Zeb is at, while I watch my chance."

She disappeared, and in a moment returned.

"He seems frantic with delight, and is yet unharmed."

"God preserve him," said George, "for his assistance is needed."

"Be careful," said Rosalind, as George approached the window.

"I shall—whew! that's a close rub!" he muttered, as a bullet pierced his cap. "There, you're past harm," he added, as he discharged his gun.

Thus the contest was kept up for over an hour. But few shots were interchanged on either side, each party becoming more careful in their action. Young Leland remained at his window, and kept a close watch upon his field; but no human being was seen. Zeb laughed, ducked his head, and made numerous threats toward his enemies, but seemed to attract no notice from them.

Now and then Rosalind spoke a word to her brother, but the suspense which the silence of their enemies had put them in, sealed their lips, and, for a long while, the silence was unbroken by either. They were startled at length by the report of Zeb's rifle, and the next minute he appeared among them, exclaiming:

"Gorra mighty! I shot out my ramrod. I seen a good chance, and blazed away 'fore I thought to take it out. It went through six of 'em, and stuck into a tree and hung 'em fast. Heigh! it's fun to see 'em."

"Here, take mine, and for God's sake, cease your jesting!" said Leland, handing his rod to him.

"Wish I could string some more up," added Zeb, as he rammed home his charge. "Yer oughter seen it, Miss Rosa. It went right frough de fust feller's eye, and den frough de oder one's foot, den frough de oder's gizzard, and half way frough de tree. Gorra, how dey wriggled! Looked just like a lot of mackerel hung up to dry. Heigh!"

At this point Leland discharged his gun, and said, without changing his position:

"They are trying to approach the house. Go, Zeb, and attend to your side. Be very sharp!"

"Yes, I's dar, stringing 'em up," he rejoined, as he turned away.

"Hark!" exclaimed Rosalind, when he had gone. "What noise is that?"

Leland listened awhile, and his heart died within him as he answered:

"Merciful Heaven! the house is on fire! All hope is now gone!"

"Shall we give ourselves up?" hurriedly asked Rosalind.

"No; come with me."

"Hurry up, massa, dey's gwine to roast us. De grease begins to siss in my face a'ready," said Zeb, as he joined them.

The fugitives retreated to the lower story, and Leland led the way to a door which opened upon the kitchen, at the end of the house. His hope was that from this they might have a chance of escaping to the wood, but a short distance off, ere they were discovered.

Cautiously opening the door, he saw with anxious, hopeful joy, that no Indians were visible.

"Now, Rosalind," he whispered, "be quick. Make for the nearest trees, and if you succeed in reaching them, pass to the river-bank and wait for me. Move softly and rapidly."

Rosalind stepped quickly out. The yells of the infuriated savages deafened her; but, although fearfully near, she saw none, and started rapidly forward. Leland watched each step with an agony of fear and anxiety which cannot be described. The trees were within twenty yards, and half the distance was passed, when Leland knew that her flight was discovered. A number of savages darted forward, but a shot from him stopped the course of the foremost. Taking advantage of the confusion which this had occasioned, Rosalind sprung away and succeeded in reaching the cover; but here, upon the very threshold of escape, she was reached and captured.

"Gorra mighty!" shouted Zeb, as he saw her seized and borne away. "Ef I don't cowhide ebery nigger of 'em for dat trick."

And clenching his hands he stalked boldly forward and demanded:

"Whar's dat lady? Ef you doesn't want to git into trouble, I calkilate you'd better bring her back in double-quick time."

Several savages sprung toward him, and Zeb prepared himself for the struggle. His huge fist felled the first and the second; but ere he could do further damage he found himself thrown down and bound.

"Well, dar, if dat ain't de meanest trick yet, servin' a decent prisoner dis way. I'll cowhide ebery one ob you. Oh, dear, I wish I had de whip!" he muttered, writhing and rolling in helpless rage upon the ground.

Leland had seen this occurrence and taken advantage of it. It had served to divert the action of the savages, and the attention of all being occupied with their two prisoners, he managed with considerable difficulty to reach the wood without being discovered.

Here, at a safe distance, he watched the progress of things. The building was now one mass of flame, which lit up the sky with a lurid, unearthly glare. The border of the forest was visible and the trunks and limbs of the trees appeared as if scorched and reddened by the consuming heat. The savages resembled demons dancing and yelling around the ruin which they had caused. It was with difficulty that Leland restrained himself from firing upon them. With a sad heart he saw the house which had sheltered him from infancy fall inward with a crash. The splinters and ashes of fire were hurled in the air and fell at his feet, and the thick volume of smoke reached him.

Yet he thought more of the captives which were in the hands of their merciless enemies. Their safety demanded his attention. Thoughtfully and despondingly he turned upon his heel and disappeared in the shadows of the great forest.

CHAPTER III.

KENT AND LESLIE.

When Roland Leslie reached his destination some miles up the Ohio, his fears and suspicions were confirmed. There had been a massacre, a week previous, of a number of settlers, and the Indians were scouring the country for more victims.

This information was given by Kent Whiteman, the person for whom he was searching. This personage was a strange character, some forty years of age, who led a wandering hunter's life, and was known by every white man for a great distance along the Ohio. Roland Leslie had made his acquaintance when but a mere lad, and they often spent weeks together hunting and roaming through the great wilderness, which was the home of both. He cherished an implacable hatred to every red-man, and they in turn often sought his life, for they had no enemy so dangerous as he.

"Yes, sir, them varmints," said he, as he leaned upon his long rifle and gazed at Leslie, "are playing particular devil in these parts, and I calkelate it's a game that two can play at."

"Them varmints," said he, "are playing particular devil in these parts."

"Jump in the boat, Kent," said Leslie, "and ride down with me; I promised George Leland that if he needed assistance I would bring it to him."

"He needs it, that's a p'inted fact, and as soon as it can conveniently reach him too."

"Well, let us be off." Leslie dipped his oars in the water and pulled out into the stream. It was the morning after the burning of the Lelands' home, which of course was unknown to them. For a few moments the boat glided rapidly down the stream, when Whiteman spoke:

"Where'd you put up last night, Leslie?"

"About ten miles down the river. I ran in under the bank and had an undisturbed night's rest?"

"Didn't hear nothin' of the red-skins?"

"No."

"Wal, it's a wonder; they're as thick as flies in August, and I calkelate I'll have rich times with 'em."

"I cannot understand how it is, Kent, that you cherish such a deadly hatred for these Indians."

"I have good reason," returned the hunter, compressing his lips.

"How long is it that you have felt thus?"

"Ever since I's a boy. Ever since that time."

"What time, Kent?"

"I have never told you, I believe, why the sight of a red-skin throws me into such a fit, have I?"

"No; I should certainly be glad to hear."

"Wal, it doesn't take long to tell. Yet how few persons know it except myself. It is nigh thirty years ago," commenced Kent, "that I lived about a dozen miles above the place that we left this morning. There I was born and lived with my old father and mother until I was ten or eleven years old.

"One dark, stormy night we war attacked by them red devils, and that father and mother were butchered before my eyes. During the confusion of the attack, I escaped to the woods and secreted m'self until it was over. It was a hard matter to lie there, scorched by the flames of your own home, and see your parents, while begging for mercy, tomahawked and slain before your eyes. But in such a position I was placed, and remained until the savages, satisfied with their bloody work, took their departure.

"When the rain, which fell in torrents, had extinguished the smoking ruins, I crawled from my hiding-place. I felt around until I come upon the cold bodies of my father and mother lyin' side by side, and then kneelin' over them, I took a fearful oath—an oath to which I have devoted my life. I swore that as long as life was given me, it should be used for revengin' the slaughter of my parents. That night these savages contracted a debt of which they little dreamed. Before they left the place, I had marked each of the dozen, and I never forgot them. For ten years I follered and tracked them, and at the end of that time I had sent the last one to his final account. Yet that did not satisfy me. I swore eternal enmity against the whole people, and as I said, it shall be carried out. While Kent is alive, he is the mortal enemy of every red-skin."

The hunter looked up in the face of Leslie, and his gleaming eyes and gnashing teeth told his earnestness. His manner and recital had impressed the latter, and he forbore speaking to him for some time.

"I should think," observed Leslie, after a short silence, "that you had nearly paid that debt, Kent."

"It is a debt which will be balanced," rejoined the hunter, "when I am unable to make any more payments."

"Well, I shouldn't want you for an enemy," added Leslie, glancing over his shoulder at the stream in front of him.

Both banks of the river at this point, and, in fact, for many miles, were lined with overhanging trees and bushes, which might afford shelter to any enemy. Kent sat in the stern and glanced suspiciously at each bank, as the boat was impelled swiftly yet silently forward, and there was not even a falling leaf that escaped his keen eye.

"Strikes me," said Leslie, leaning on his oars, "that we are in rather a dangerous vicinity. Those thick bushes along the shore, over there, might easily contain a few red gentlemen."

"Don't be alarmed," returned the hunter, "I'll keep a good watch. They've got to make some movement before they can harm us, and I'll be sure to see them. The river's wide, too, and there ain't so much to fear, after all."

Leslie again dipped his oars, and the boat shot forward in silence. Nothing but the suppressed dip of the slender ashen blades, or the dull sighing of the wind through the tree-tops, broke the silence of the great solitude. Suddenly, as Leslie bent forward and gazed into the hunter's face, he saw him start and gaze anxiously at the right shore, some distance ahead.

"What's the matter?" asked Leslie.

"Just wait a minute," returned the hunter, rising and gazing in the same direction. "Stop the boat. Back water!" he added, in a hurried tone.

Leslie did as he was bidden, and again spoke:

"What is it, Kent?"

"Do you see them bushes hangin' a little further out in the stream than the others?"

"Yes; what of them?"

"Watch them a minute. There—look quick!" said Kent.

"I can see a fluttering among the branches, as if a bird had flown from it," answered Leslie.

"Wal, them birds is Indians, that's all," remarked the hunter, dropping composedly back into the boat. "Go ahead!"

"They will fire into us, no doubt. Had I not better run in to the other shore?"

"No; there may be a host of 'em there. Keep in the middle of the stream, and we'll give 'em the slip yet."

It must be confessed that Leslie experienced rather strange sensations as he neared the locality which had excited their suspicion, especially when he knew that he was exposed to any shot that they might feel inclined to give. A shudder ran through his frame, when, directly opposite the spot, he distinctly heard a groan of agony.

Kent made a motion for him to cease rowing. Bending their heads down and listening, they again heard that now loud, agonizing expression of mortal pain.

As soon as Leslie was certain that the sound proceeded from some being in distress, he headed the boat toward the shore.

"Stop!" commanded Kent; "you should have more sense than that."

"But will you not assist a person in distress?" asked he, gazing reproachfully into his face.

"Who's in distress?"

"Oh, Gorra mighty! I's been dyin'," now came from the shore.

"Hallo there! what's wantin'?" called Whiteman.

"Help, help, 'fore dis Indian gentleman—'fore I dies from de wounds dat dey's given me."

"I've heard that voice before," remarked Kent to Leslie, in an undertone.

"So have I," replied the latter. "Why, it is George Leland's negro; he wouldn't decoy us into danger. Let us go in."

"Wait until I speak further with him." (Then, to the person upon shore): "What might be your name?"

"Zeb Langdon. Isn't dat old Kent?"

"Yes; how came you in this scrape, Zeb?"

"Gorra mighty! I didn't come into it. Dem red dogs—dese here nice fellers—brought me here 'bout two months ago, and den dey all fired at me fur two or free days, and den dey hung me up and left me to starve to death. Boo-hoo-oo!"

"But," said Leslie, "you were at home yesterday when I came up the river."

"Yes; dey burned down de house last night, and cooked us all and eat us up. I's come to live ag'in, and crawled down here to get you fellers to take me home; but, Lord bless you, don't come ashore—blast you, quit a hittin' me over de head," added the negro, evidently to some one near him.

Leslie and Whiteman exchanged significant glances, and silently worked the boat further from the land.

"Who is that you spoke to?" asked the former, when they were at a safe distance.

"Dis yere blasted limb reached down and pulled my wool," replied the negro, with perfect nonchalance.

"Where is George Leland?" asked Leslie.

"Dunno; slipped away from dese yere nice fellers what's pulled all de wool out of me head, and is tellin' me a lot o' yarns to tell you. Gorra mighty! can't you let a feller 'lone, when he's yarnin' as good as he can?"

"Where is Miss Leland?"

"How does I know? A lot of 'em run off wid her last night."

"Oh God! what I expected," said Leslie, dropping his voice, and gazing with an agonizing look at Whiteman. The latter, regardless of his emotion, continued his conversation with Zeb.

"Are you hurt any?"

"Considerable."

"Now, Zeb, tell the truth. Did they capture George Leland?"

"Bless you, no. He got away during de trouble."

"Did they get Miss Leland?"

"'Deed they did."

"Is she with you?"

"No. It took forty of 'em to watch me and de rest."

Here the negro's words were cut short with a jerk, and he gave vent to a loud groan.

"Gorra mighty!" he ejaculated, in fury. "Come ashore, Mr. Whiteman and Mr. Leslie. Come quick, and let dese yer fellers got you. Dey wants yer too."

"Are there any of the imps with you?" asked Kent, more for amusement than anything else.

"What shall I tell him?" the negro asked, in a husky whisper, loud enough to be plainly heard by the two in the boat.

"Dey say dar ain't any of 'em. Talk yourself, if dat doesn't suit you," he added, in great wrath.

"Three cheers for you," shouted Whiteman. "Are there any of 'em upon the other side?"

"Dese fellers say dey am all dar. Gorra, don't kill me."

"Good; you're the best nigger 'long the 'Hio. I guess we'll go over to the other side and visit them."

So saying, Kent seized the oars and pulled for the opposite shore. He had not taken more than a couple of strokes when a dozen rifles cracked simultaneously from the bushes, and as many bullets struck the boat and glanced over the water.

"Drop down," he whispered to Leslie. Instead of doing the same himself, he bent the more vigorously to his oars. A few minutes sufficed to carry them so far down that little danger was to be apprehended from the Indians, who uttered their loudest shouts and discharged their rifles, as they passed beyond their reach.

"That's too good a chance to be lost," muttered the ranger, bringing his long rifle to his shoulder. Leslie followed the direction of his aim, and saw a daring savage standing boldly out to view, and making furious gesticulations toward them. The next instant Kent's rifle uttered its sharp report, and the Indian, with a yell, sprung several feet in the air, and fell to the ground.

"That was a good shot," remarked Leslie, gazing at the fallen body.

"Yes, and it's done just what I wanted it to," replied Kent, heading the boat toward shore.

"They are going to pursue us, are they not?" asked Leslie.

"Yes, and we'll have fun," added the ranger, as the boat touched the shore, and he sprung out.

"Come along and make up yer mind for a long run," said he, glancing furtively toward the savages.

Leslie sprung after him, and they darted away into the forest.

When Whiteman had fired his fatal shot the Indians were so infuriated, that, setting up their demoniac yells, they plunged down the banks of the stream, determined to revenge their fallen companion.