A Young Hero Or, Fighting to Win

Edward S. Ellis

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

A Table of Contents has been added.

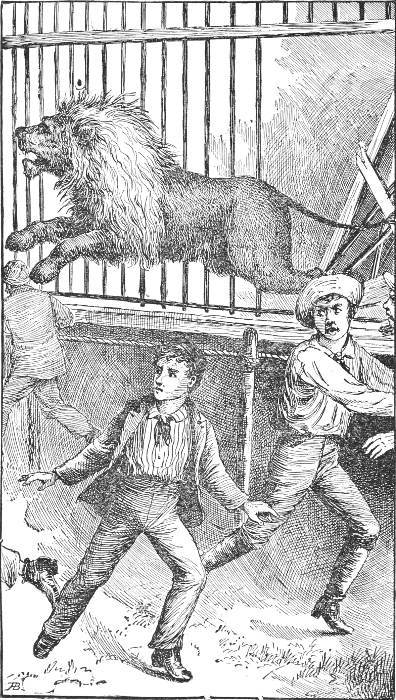

"The lion sprang through the air among the terrified group."—(See page 71.)

A YOUNG HERO;

OR,

Fighting to Win.

By EDWARD S. ELLIS,

Author of

"Adrift in the Wilds," etc., etc.

ILLUSTRATED.

NEW YORK:

A. L. BURT, PUBLISHER.

Copyright 1888, by A. L. Burt.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | ||

| CHAPTER I. | THE PEACEMAKER. | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | THE CALL TO SCHOOL. | 9 |

| CHAPTER III. | STARTLING NEWS. | 17 |

| CHAPTER IV. | ON GUARD. | 32 |

| CHAPTER V. | BRAVE WORK. | 41 |

| CHAPTER VI. | ON THE OUTSIDE. | 56 |

| CHAPTER VII. | "THE LION IS LOOSE!" | 64 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | A DAY OF EXCITEMENT IN TOTTENVILLE. | 72 |

| CHAPTER IX. | SEVERAL MISHAPS. | 88 |

| CHAPTER X. | A BRAVE ACT. | 97 |

| CHAPTER XI. | A REWARD WELL EARNED. | 104 |

| CHAPTER XII. | A BUSINESS TRANSACTION. | 119 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | THE EAVESDROPPER. | 133 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | FRED'S BEST FRIEND. | 146 |

| CHAPTER XV. | THE MEETING IN THE WOOD. | 167 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | BUD'S MISHAPS. | 175 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | TWO UNEXPECTED VISITORS. | 182 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | EUREKA! | 196 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | A SLIGHT MISTAKE. | 204 |

| CHAPTER XX. | ALL IN GOOD TIME. | 212 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | HOW IT WAS DONE. | 219 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | AN ATTEMPTED RESCUE. | 226 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | THE SILVERWARE RETURNED. | 241 |

| THE WALNUT ROD. | BY R. F. COLWELL. | 251 |

| HOW THE HATCHET WAS BURIED. | BY OCTAVIA CARROLL. | 260 |

| HANSCHEN AND THE HARES. | FROM THE GERMAN, BY ELLEN T. SULLIVAN. | 275 |

A YOUNG HERO.

CHAPTER I. THE PEACEMAKER.

"A fight! A fight! Form a ring!" A dozen or more excited boys shouted these words, and, rushing forward, hastily formed a ring around two playmates who stood in the middle of the road, their hats off, eyes glaring, fists clenched, while they panted with anger, and were on the point of flying at one another with the fury of young wildcats.

They had been striking, kicking and biting a minute before over some trifling dispute, and they had now stopped to take breath and gather strength before attacking each other again with a fierceness which had become all the greater from the brief rest.

"Give it to him, Sam! Black his eyes for him! Hit him under the ear! Bloody his nose!"

Thus shouted the partisans of Sammy McClay, who had thrown down his school books, and pitched into his opponent, as though he meant to leave nothing of him.

The friends of Joe Hunt were just as loud and urgent.

"Sail in, Joe! You can whip him before he knows it! Kick him! Don't be a coward! You've got him!"

A party of boys and girls were on their way home from the Tottenville public school, laughing, romping and frolicking with each other, when, all at once, like a couple of bantam chickens, these two youngsters began fighting.

The girls looked on in a horrified way, whispering to each other, and declaring that they meant to tell Mr. McCurtis, the teacher, including also the respective mothers of the young pugilists.

The other boys, as is nearly always the case, did their utmost to urge on the fight, and, closing about Sam and Joe, taunted them in loud voices, and appealed to them to resume hostilities at once.

The fighters seemed to be equally matched, and, as they panted and glared, each waited for the other to renew the struggle by striking the first blow.

"You just hit me if you dare! that's all I want!" exclaimed Sammy McClay, shaking his head so vigorously that he almost bumped his nose against that of Joe Hunt, who was just as ferocious, as he called back:

"You touch me, Sam McClay, just touch me! I dare you! double, double dare you."

Matters were fast coming to the exploding point, but not fast enough to suit the audience. Jimmy Emery picked up a chip, and running forward, balanced it in a delicate position on the shoulder of Sam McClay, and, addressing his opponent said: "Knock that off, Joe!"

"Yes, knock it off!" shouted Sam, "I dare you to knock it off!"

"Who's afraid?" demanded Joe, looking at the chip, with an expression which showed he meant to flip it to the ground.

"Well, you just try it—that's all!"

Joe was in the very act of upsetting the bit of wood, when a boy about their own age, with a flapping straw hat, and with his trousers rolled far above his knees, ran in between the two, and used his arms with so much vigor that the contestants were thrown quite a distance apart.

"What's the matter with you fellows?" demanded this boy, glancing from one to the other. "What do you want to make fools of yourselves for?"

"He run against me," said Sammy McClay, "and knocked me over Jim Emery."

"Well, what of it?" asked the peacemaker. "Will it make you feel any better to get your head cracked? What's the matter of you, Joe Hunt?" he added, turning his glance without changing his position, toward the other pugilist.

"What did he punch me for, when I stubbed my toe and run agin him?" and Joe showed a disposition just then to move around his questioner, so as to get at the offender.

The other boys did not like this interference with their enjoyment, and called on the peacemaker to let them have it out; but he stood his ground, and shaking his right fist at Sammy McClay, and his left at Joe Hunt, he told them they must let each other alone, or he would whip them both.

This created some laughter, for the lad was no older than they, and hardly as tall as either; but there is a great deal in the manner of a man or boy. If his flashing eye, his stern voice, and look of determination show that he means what he says, or is in dead earnest, his opponent generally yields.

At the critical juncture, the girls added their voices in favor of peace, and their champion, stooping down, picked up the hats from the ground, and jammed them upon their owners' heads with a force that nearly threw them off their feet.

"That's enough! now come on!"

Sam and Joe walked along, rather sullenly at first. They glowered on each other, shook their heads, muttered and seemed on the point of renewing the contest more than once; but the passions of childhood are brief, and the storm soon blew over. Before the boys and girls had reached the cross-roads, Sam McClay and Joe Hunt were playing with each other like the best of friends, as indeed they were.

The name of the lad who had stopped the fight was Fred Sheldon, and he is the hero of this story.

CHAPTER II. THE CALL TO SCHOOL.

Fred Sheldon, as I have said, is the hero of this story.

He was twelve years of age, the picture of rosy health, good nature, bounding spirits and mental strength. He was bright and well advanced in his studies, and as is generally the case with such vigorous youngsters he was fond of fun, which too often, perhaps, passed the line of propriety and became mischief.

On the Monday morning after the fight, which Fred Sheldon interrupted, some ten or twelve boys stopped on their way to the Tottenville Public School to admire in open-mouthed wonder, the gorgeous pictures pasted on a huge framework of boards, put up for the sole purpose of making such a display.

These flaming posters were devoted to setting forth the unparalleled attractions of Bandman's great menagerie and circus, which was announced to appear in the well-known "Hart's Half-Acre," near the village of Tottenville.

These scenes, in which elephants, tigers, leopards, camels, sacred cows, and indeed an almost endless array of animals were shown on a scale that indicated they were as high as a meeting-house, in which the serpents, it unwound from the trees where they were crushing men and beasts to death, would have stretched across "Hart's Half-Acre" (which really contained several acres), those frightful encounters, in which a man, single-handed, was seen to be spreading death and destruction with a clubbed gun among the fierce denizens of the forest; all these had been displayed on the side of barns and covered bridges, at the cross-roads, and indeed in every possible available space for the past three weeks; and, as the date of the great show was the one succeeding that of which we are speaking, it can be understood that the little village of Tottenville and the surrounding country were in a state of excitement such as had not been known since the advent of the preceding circus.

Regularly every day the school children had stopped in front of the huge bill-board and studied and admired and talked over the great show, while those who expected to go in the afternoon or evening looked down in pity on their less fortunate playmates.

The interest seemed to intensify as the day approached, and, now that it was so close at hand, the little group found it hard to tear themselves away from the fascinating scenes before them.

Down in one corner of the board was the picture of a hyena desecrating a cemetery, as it is well known those animals are fond of doing. This bad creature, naturally enough, became very distasteful to the boys, who showed their ill-will in many ways.

Several almost ruined their new shoes by kicking him, while others had pelted him with stones, and still others, in face of the warning printed in big letters, had haggled him dreadfully with their jack-knives.

It was a warm summer morning and most of the boys not only were bare-footed, but had their trousers rolled above their knees, and, generally, were without coat or vest.

"To-morrow afternoon the show will be here," said Sammy McClay, smacking his lips and shaking his head as though he tasted a luscious morsel, "and I'm going."

"How are you going," asked Joe Hunt, sarcastically, "when your father said he wouldn't give you the money?"

"Never you mind," was the answer, with another significant shake of the head. "I'm goin'—that's all."

"Goin' to try and crawl under the tent. I know. But you can't do it. You'll get a whack from the whip of the man that's watching that you'll feel for six weeks. Don't I know—'cause, didn't I try it?"

"I wouldn't be such a dunce as you; you got half way under the tent and then stuck fast, so you couldn't go backward or forward, and you begun to yell so you like to broke up the performance, and when the man come along why he had the best chance in the world to cowhide you, and he did it. I think I know a little better than that."

At this moment, Mr. Abijah McCurtis, the school teacher in the little stone school-house a hundred yards away, solemnly lifted his spectacles from his nose to his forehead, and grasping the handle of his large cracked bell walked to the door and swayed it vigorously for a minute or so.

This was the regular summons for the boys and girls to enter school, and he had sent forth the unmusical clangor, summer and winter, for a full two-score years.

Having called the pupils together, the pedagogue sat down, drew his spectacles back astride of his nose, and resumed setting copies in the books which had been laid on his desk the day before.

In a minute or so the boys and girls came straggling in, but the experienced eye of the teacher saw that several were missing.

Looking through the open door he discovered where the four delinquent urchins were; they were still standing in front of the great showy placards, studying the enchanting pictures, as they had done so many times before.

They were all talking earnestly, Sammy McClay, Joe Hunt, Jimmy Emery and Fred Sheldon, and they had failed for the first time in their lives to hear the cracked bell.

Most teachers, we are bound to believe, would have called the boys a second time or sent another lad to notify them, but the present chance was one of those which, unfortunately, the old-time pedagogue was glad to have, and Mr. McCurtis seized it with pleasure.

Rising from his seat, he picked up from where it lay across his desk a long, thin switch, and started toward the four barefooted lads, who were admiring the circus pictures.

Nothing could have been more inviting, for, not only were they barefooted, but each had his trousers rolled to the knee, and Fred Sheldon had drawn and squeezed his so far that they could go no further. His plump, clean legs offered the most inviting temptation to the teacher, who was one of those sour old pedagogues, of the long ago, who delighted in seeing children tortured under the guise of so-called discipline.

"I don't believe in wearing trousers in warm weather," said Fred, when anybody looked wonderingly to see whether he really had such useful garments on, "and that's why I roll mine so high up. Don't you see I'm ready to run into the water, and——"

"How about going through the bushes and briars?" asked Joe Hunt.

"I don't go through 'em," was the crushing answer. "I feel so supple and limber that I just jump right over the top. I tell you, boys, that you ought to see me jump——"

Fred's wish was gratified, for at that moment he gave such an exhibition of jumping as none of his companions had ever seen before. With a shout he sprang high in air, kicking out his bare legs in a frantic way, and ran with might and main for the school-house.

The other three lads did pretty much the same, for the appearance of the teacher among them was made known by the whizzing hiss of his long, slender switch, which first landed on Fred's legs, and was then quickly transferred to the lower limbs of the other boys, the little company immediately heading for the school house, with Fred Sheldon at the front.

Each one shouted, and made a high and frantic leap every few steps, believing that the teacher was close behind him with upraised stick, and looking for the chance to bring it down with effect.

"I'll teach you not to stand gaping at those pictures," shouted Mr. McCurtis, striding wrathfully after them.

A man three-score years old cannot be expected to be as active as a boy with one-fifth as many years; but the teacher had the advantage of being very tall and quite attenuated, and for a short distance he could outrun any of his pupils.

The plump, shapely legs of Fred Sheldon, twinkling and doubling under him as he ran, seemed to be irresistibly tempting to Mr. McCurtis, who, with upraised switch, dashed for him like a thunder-gust, paying no attention to the others, who ducked aside as he passed.

"It's your fault, you young scapegrace," called out the pursuer, as he rapidly overhauled him; "you haven't been thinking of anything else but circuses for the past month and I mean to whip it out of you—good gracious sakes!"

Fred Sheldon had seen how rapidly the teacher was gaining, and finding there was no escape, resorted to the common trick among boys of suddenly falling flat on his face while running at full speed.

The cruel-hearted teacher at that very moment made a savage stroke, intending to raise a ridge on the flesh of the lad, who escaped it by a hair's breadth, as may be said.

The spiteful blow spent itself in vacancy, and the momentum spun Mr. McCurtis around on one foot, so that he faced the other way. At that instant his heels struck the prostrate form of the crouching boy, and he went over, landing upon his back, his legs pointing upward, like a pair of huge dividers.

There is nothing a boy perceives so quickly as a chance for fun, and before the teacher could rise, Sammy McClay also went tumbling over the grinning Fred Sheldon, with such violence, indeed, that he struck the bewildered instructor as he was trying to adjust his spectacles to see where he was.

Then came Joe Hunt and Jimmy Emery, and Fred Sheldon capped the climax by running at full speed and jumping on the struggling group, spreading out his arms and legs in the effort to bear them down to the earth.

But the difficulty was that Fred was not very heavy nor bony, so that his presence on top caused very little inconvenience, the teacher rising so hurriedly that Fred fell from his shoulders, and landed on his head when he struck the earth.

The latter was dented, but Fred wasn't hurt at all, and he and his friends scrambled hastily into the school-house, where the other children were in an uproar, fairly dancing with delight at the exhibition, or rather "circus," as some of them called it, which took place before the school-house and without any expense to them.

By the time the discomfited teacher had got upon his feet and shaken himself together, the four lads were in school, busily engaged in scratching their legs and studying their lessons.

Mr. McCurtis strode in a minute later switch in hand, and in such a grim mood that he could only quiet his nerves by walking around the room and whipping every boy in it.

CHAPTER III. STARTLING NEWS.

Fred Sheldon was the only child of a widow, who lived on a small place a mile beyond the village, and managed to eke out a living thereon, assisted by a small pension from the government, her husband having been killed during the late war.

A half-mile beyond stood a large building, gray with age and surrounded with trees, flowers and climbing vines. The broad bricks of which it was composed were known to have been brought from Holland long before the revolution, and about the time when George Washington was hunting for the cherry-tree with his little hatchet.

In this old structure lived the sisters Perkinpine—Annie and Lizzie—who were nearly seventy years of age. They were twins, had never been married, were generally known to be wealthy, but preferred to live entirely by themselves, with no companion but three or four cats, and not even a watch-dog.

Their ancestors were among the earliest settlers of the section, and the Holland bricks could show where they had been chipped and broken by the bullets of the Indians who howled around the solid old structure, through the snowy night, as ravenous as so many wolves to reach the cowering women and children within.

The property had descended to the sisters in regular succession, and there could be no doubt they were rich in valuable lands, if in nothing else. Their retiring disposition repelled attention from their neighbors, but it was known there was much old and valuable silver, and most probably money itself, in the house.

Michael Heyland was their hired man, but he lived in a small house some distance away, where he always spent his nights.

Young Fred Sheldon was once sent over to the residence of the Misses Perkinpine after a heavy snowstorm, to see whether he could do anything for the old ladies. He was then only ten years old, but his handsome, ruddy face, his respectful manner, and his cheerful eagerness to oblige them, thawed a great deal of their natural reserve, and they gradually came to like him.

He visited the old brick house quite often, and frequently bore substantial presents to his mother, though, rather curiously, the old ladies never asked that she should pay them a visit.

The Misses Perkinpine lived very well indeed, and Fred Sheldon was not long in discovering it. When he called there he never could get away without eating some of the vast hunks of gingerbread and enormous pieces of thick, luscious pie, of which Fred, like all boys, was very fond.

There was no denying that Fred had established himself as a favorite in that peculiar household, as he well deserved to be.

On the afternoon succeeding his switching at school he reached home and did his chores, whistling cheerily in the meanwhile, and thinking of little else than the great circus on the morrow, when he suddenly stopped in surprise upon seeing a carriage standing in front of the gate.

Just then his mother called him to the house and explained:

"Your Uncle William is quite ill, Fred, and has sent for me. You know he lives twelve miles away, and it will take us a good while to get there; if you are afraid to stay here alone you can go with us."

Fred was too quick to trip himself in that fashion. To-morrow was circus day, and if he went to his Uncle Will's, he might miss it.

"Miss Annie asked me this morning to go over and see them again," he said, alluding to one of the Misses Perkinpine, "and they'll be mighty glad to have me there."

"That will be much better, for you will be so near home that you can come over in the morning and see that everything is right, but I'm afraid you'll eat too much pie and cake and pudding and preserves."

"I ain't afraid," laughed Fred, who kissed his mother good-by and saw the carriage vanish down the road in the gloom of the gathering darkness. Then he busied himself with the chores, locked up the house and put everything in shape preparatory to going away.

He was still whistling, and was walking rapidly toward the gate, when he was surprised and a little startled by observing the figure of a man, standing on the outside, as motionless as a stone, and no doubt watching him.

He appeared to be ill-dressed, and Fred at once set him down as one of those pests of society known as a tramp, who had probably stopped to get something to eat.

"What do you want?" asked the lad, with an air of bravery which he was far from feeling, as he halted within two or three rods of the unexpected guest, ready to retreat if it should become necessary.

"I want you to keep a civil tongue in your head," was the answer, in a harsh rasping voice.

"I didn't mean to be uncivil," was the truthful reply of Fred, who believed in courtesy to every one.

"Who lives here, then?" asked the other in the same gruff voice.

"My mother, Mrs. Mary Sheldon, and myself, but my mother isn't at home."

The stranger was silent a moment, and then looking around, as if to make sure that no one was within hearing, asked in a lower voice:

"Can you tell me where the Miss Perkinpines live?"

"Right over yonder," was the response of the boy, pointing toward the house, which was invisible in the darkness, but a star-like twinkle of light showed where it was, surrounded by trees and shrubbery.

Fred came near adding that he was on his way there, and would show him the road, but a sudden impulse restrained him.

The tramp-like individual peered through the gloom in the direction indicated, and then inquired:

"How fur is it?"

"About half a mile."

The stranger waited another minute or so, as if debating with himself whether he should ask some other questions that were in his mind; but, without another word, he moved away and speedily disappeared from the road.

Although he walked for several paces on the rough gravel in front of the gate, the lad did not hear the slightest sound. He must have been barefooted, or more likely, wore rubber shoes.

Fred Sheldon could not help feeling very uncomfortable over the incident itself. The question about the old ladies, and the man's looks and manner impressed him that he meant ill toward his good friends, and Fred stood a long time asking himself what he ought to do.

He thought of going down to the village and telling Archie Jackson, the bustling little constable, what he feared, or of appealing to some of the neighbors; and pity it is he did not do so, but he was restrained by the peculiar disposition of the Misses Perkinpine, who might be very much displeased with him.

As he himself was about the only visitor they received, and as they had lived so long by themselves, they would not thank him, to say the least—that is, viewing the matter from his standpoint.

"I'll tell the ladies about it," he finally concluded, "and we'll lock the doors and sit up all night. I wish they had three or four dogs and a whole lot of guns; or if I had a lasso," he added, recalling one of the circus pictures, "and the tramp tried to get in, I'd throw it over his head and pull him half way to the top of the house and let him hang there until he promised to behave himself."

Fred's head had been slightly turned by the circus posters, and it can hardly be said that he was the best guard the ladies could have in case there were any sinister designs on the part of the tramp.

But the boy was sure he was never more needed at the old brick house than he was on that night, and hushing his whistle, he started up the road in the direction taken by the stranger.

It was a trying ordeal for the little fellow, whose chief fear was that he would overtake the repulsive individual and suffer for interfering with his plans.

There was a faint moon in the sky, but its light now and then was obscured by the clouds which floated over its face. Here and there, too, were trees, beneath whose shadows the boy stepped lightly, listening and looking about him, and imagining more than once he saw the figure dreaded so much.

But he observed nothing of him, nor did he meet any of his neighbors, either in wagons or on foot, and his heart beat tumultuously when he drew near the grove of trees, some distance back from the road, in the midst of which stood the old Holland brick mansion.

To reach it it was necessary to walk through a short lane, lined on either hand by a row of stately poplars, whose shade gave a cool twilight gloom to the intervening space at mid-day.

"Maybe he isn't here, after all," said Fred to himself, as he passed through the gate of the picket fence surrounding the house, "and I guess——"

Just then the slightest possible rustling caught his ear, and he stepped back behind the trunk of a large weeping willow.

He was not mistaken; some one was moving through the shrubbery at the corner of the house, and the next minute the frightened boy saw the tramp come stealthily to view, and stepping close to the window of the dining-room, peer into it.

As the curtain was down it was hard to see how he could discover anything of the inmates, but he may have been able to detect something of the interior by looking through at the side of the curtain, or possibly he was only listening.

At any rate he stood thus but a short time, when he withdrew and slowly passed from view around the corner.

The instant he was gone Fred moved forward and knocked softly on the door, so softly indeed, that he had to repeat it before some one approached from the inside and asked who was there.

When his voice was recognized the bolt was withdrawn and he was most cordially welcomed by the old ladies, who were just about to take up their knitting and sewing, having finished their tea.

When Fred told them he had come to stay all night and hadn't had any supper, they were more pleased than ever, and insisted that he should go out and finish a large amount of gingerbread, custard and pie, for the latter delicacy was always at command.

"I'll eat some," replied Fred, "but I don't feel very hungry."

"Why, what's the matter?" asked Miss Annie, peering over her spectacles in alarm; "are you sick? If you are we've got lots of castor oil and rhubarb and jalap and boneset; shall I mix you up some?"

"O my gracious! no—don't mention 'em again; I ain't sick that way—I mean I'm scared."

"Scared at what? Afraid there isn't enough supper for you?" asked Miss Lizzie, looking smilingly down upon the handsome boy.

"I tell you," said Fred, glancing from one to the other, "I think there's a robber going to try and break into your house to-night and steal everything you've got, and then he'll kill you both, and after that I'm sure he means to burn down the house, and that'll be the last all of you and your cats."

When the young visitor made such a prodigious declaration, he supposed the ladies would scream and probably faint away. But the very hugeness of the boy's warning caused emotions the reverse of what he anticipated.

They looked kindly at him a minute or so and then quietly smiled.

"What a little coward you are, Fred," said Miss Annie; "surely there is nobody who would harm two old creatures like us."

"But they want your money," persisted Fred, still standing in the middle of the floor.

Both ladies were too truthful to deny that they had any, even to such a child, and Lizzie said:

"We haven't enough to tempt anybody to do such a great wrong."

"You can't tell about that, then I 'spose some of those silver dishes must be worth a great deal."

"Yes, so they are," said Annie, "and we prize them the most because our great, great, great-grandfather brought them over the sea a good many years ago, and they have always been in our family."

"But," interposed Lizzie, "we lock them up every night."

"What in?"

"A great big strong chest."

"Anybody could break it open, though."

"Yes, but it's locked; and you know it's against the law to break a lock."

"Well," said Fred, with a great sigh, "I hope there won't anybody disturb you, but I hope you will fasten all the windows and doors to-night."

"We always do; and then," added the benign old lady, raising her head so as to look under her spectacles in the face of the lad, "you know we have you to take care of us."

"Have you got a gun in the house?"

"Mercy, yes; there's one over the fire-place, where father put it forty years ago."

"Is there anything the matter with it?"

"Nothing, only the lock is broke off, and I think father said the barrel was bursted."

Fred laughed in spite of himself.

"What under the sun is such an old thing good for?"

"It has done us just as much good as if it were a new cannon—but come out to your supper."

The cheerful manner of the old ladies had done much to relieve Fred's mind of his fears, and a great deal of his natural appetite came back to him.

He walked into the kitchen, where he seated himself at a table on which was spread enough food for several grown persons, and telling him he must not leave any of it to be wasted, the ladies withdrew, closing the door behind them, so that he might not be embarrassed by their presence.

"I wonder whether there's any use of being scared," said Fred to himself, as he first sunk his big, sound teeth into a huge slice of buttered short-cake, on which some peach jam had been spread! "If I hadn't seen that tramp looking in at the window I wouldn't feel so bad, and I declare," he added in dismay, "when they questioned me, I never thought to tell 'em that. Never mind, I'll give 'em the whole story when I finish five or six slices of this short-cake and some ginger-cake, and three or four pieces of pie, and then, I think, they'll believe I'm right."

For several minutes the boy devoted himself entirely to his meal, and had the good ladies peeped through the door while he was thus employed they would have been highly pleased to see how well he was getting along.

"I wish I was an old maid and hadn't anything to do but to cook nice food like this and play with the cats—my gracious!"

Just then the door creaked, and, looking up, Fred Sheldon saw to his consternation the very tramp of whom he had been thinking walk into the room and approach the table.

His clothing was ragged and unclean, a cord being drawn around his waist to keep his coat together, while the collar was up so high about his neck that nothing of the shirt was visible.

His hair was frowsy and uncombed, as were his huge yellow whiskers, which seemed to grow up almost to his eyes, and stuck out like the quills on a porcupine.

As the intruder looked at the boy and shuffled toward him, in his soft rubber shoes, he indulged in a broad grin, which caused his teeth to shine through his scraggly beard.

He held his hat, which resembled a dishcloth, as much as anything, in his hand, and was all suavity.

His voice sounded as though he had a bad cold, with now and then an odd squeak. As he bowed he said:

"Good evening, young man; I hope I don't intrude."

As he approached the table and helped himself to a chair, the ladies came along behind him, Miss Lizzie saying:

"This poor man, Frederick, has had nothing to eat for three days, and is trying to get home to his family. I'm sure you will be glad to have him sit at the table with you."

"Yes, I'm awful glad," replied the boy, almost choking with the fib. "I was beginning to feel kind of lonely, but I'm through and he can have the table to himself."

"You said you were a shipwrecked sailor, I believe?" was the inquiring remark of Miss Lizzie, as the two sisters stood in the door, beaming kindly on the tramp, who began to play havoc with the eatables before him.

"Yes, mum; we was shipwrecked on the Jarsey coast; I was second mate and all was drowned but me. I hung to the rigging for three days and nights in the awfullest snow storm you ever heard of."

"Mercy goodness," gasped Annie; "when was that?"

"Last week," was the response, as the tramp wrenched the leg of a chicken apart with hands and teeth.

"Do they have snow storms down there in summer time?" asked Fred, as he moved away from the table.

The tramp, with his mouth full of meat, and with his two hands grasping the chicken-bone between his teeth, stopped work and glared at the impudent youngster, as if he would look him through and through for daring to ask the question.

"Young man," said he, as he solemnly resumed operations, "of course, they have snow storms down there in summer time; I'm ashamed of your ignorance; you're rather small to put in when grown-up folks are talking, and I'd advise you to listen arter this."

Fred concluded he would do so, using his eyes meanwhile.

"Yes, mum," continued the tramp; "I was in the rigging for three days and nights, and then was washed off by the breakers and carried ashore, where I was robbed of all my clothing, money and jewels."

"Deary, deary me!" exclaimed the sisters in concert. "How dreadful."

"You are right, ladies, and I've been tramping ever since."

"How far away is your home?"

"Only a hundred miles, or so."

"You have a family, have you?"

"A wife and four babies—if they only knowed what their poor father had passed through—excuse these tears, mum."

The tramp just then gave a sniff and drew his sleeve across his forehead, but Fred Sheldon, who was watching him closely, did not detect anything like a tear.

But he noted something else, which had escaped the eyes of the kind-hearted ladies.

The movement of the arm before the face seemed to displace the luxuriant yellow beard. Instead of sitting on the countenance as it did at first, even in its ugliness, it was slewed to one side.

Only for a moment, however, for by a quick flirt of the hand, as though he were scratching his chin, he replaced it.

And just then Fred Sheldon noticed another fact. The hand with which this was done was as small, white and fair as that of a woman—altogether the opposite of that which would have been seen had the tramp's calling been what he claimed.

The ladies, after a few more thoughtful questions, withdrew, so that their guest might not feel any delicacy in eating all he wished—an altogether unnecessary step on their part.

Fred went out with them, but after he had been gone a few minutes he slyly peeped through the crack of the door, without the ladies observing the impolite proceeding.

The guest was still doing his best in the way of satisfying his appetite, but he was looking around the room, at the ceiling, the floor, the doors, windows and fire-place, and indeed at everything, as though he was greatly interested in them, as was doubtless the case.

All at once he stopped and listened, glancing furtively at the door, as if he feared some one was about to enter the room.

Then he quietly rose, stepped quickly and noiselessly to one of the windows, took out the large nail which was always inserted over the sash at night to keep it fastened, put it in his pocket, and, with a half chuckle and grin, seated himself again at the table.

At the rate of eating which was displayed, he soon finished, and, wiping his greasy hands on his hair, he gave a great sigh of relief, picked up his slouchy hat, and moved toward the door leading to the room in which the ladies sat.

"I'm very much obleeged to you," said he, bowing very low, as he shuffled toward the outer door, "and I shall ever remember you in my prayers; sorry I can't pay you better, mums."

The sisters protested they were more than repaid in the gratitude he showed, and they begged him, if he ever came that way, to call again.

He promised that he would be glad to do so, and departed.

"You may laugh all you're a mind to," said Fred, when he had gone, "but that's the man I saw peeping in the window, and he means to come back here to-night and rob you."

The boy told all that he knew, and the ladies, while not sharing his fright, agreed that it was best to take extra precautions in locking up.

CHAPTER IV. ON GUARD.

The sisters Perkinpine always retired early, and, candle in hand, they made the round of the windows and doors on the first floor.

When they came to the window from which the nail had been removed, Fred told them he had seen the tramp take it out, and he was sure he would try and enter there.

This served to add to the uneasiness of the sisters, but they had great confidence in the security of the house, which had never been disturbed by burglars, so far as they knew, in all its long history.

"The chest where we keep the silver and what little money we have," said Lizzie, "is up-stairs, next to the spare bed-room."

"Leave the door open and let me sleep there," said Fred, stoutly.

"Gracious alive, what can you do if they should come?" was the amazed inquiry.

"I don't know as I can do anything, but I can try; I want that old musket that's over the fire-place, too."

"Why, it will go off and kill you."

Fred insisted so strongly, however, that he was allowed to climb upon a chair and take down the antiquated weapon, covered with rust and dust.

When he came to examine it he found that the description he had heard was correct—the ancient flintlock was good for nothing, and the barrel, when last discharged, must have exploded at the breach, for it was twisted and split open, so that a load of powder could only injure the one who might fire it, were such a feat possible.

The sisters showed as much fear of it when it was taken down as though it were in good order, primed and cocked, and they begged the lad to restore it to its place as quickly as possible.

But he seemed to think he had charge of the business for the evening, and, bidding them good-night, he took his candle and went to his room, which he had occupied once or twice before.

It may well be asked what young Fred Sheldon expected to do with such a useless musket, should emergency arise demanding a weapon.

Indeed, the boy would have found it hard to tell himself, excepting that he hoped to scare the man or men away by the pretence of a power which he did not possess.

Now that the young hero was finally left alone, he felt that he had a most serious duty to perform.

The spare bedroom which was placed at his disposal was a large, old-fashioned apartment, with two windows front and rear, with a door opening into the next room, somewhat smaller in size, both being carpeted, while the smaller contained nothing but a few chairs and a large chest, in which were silver and money worth several thousand dollars.

"I'll set the candle in there on the chest," concluded Fred, "and I'll stay in here with the gun. If he comes up-stairs and gets into the room I'll try and make him believe I've got a loaded rifle to shoot him with."

The door opening outward from each apartment had nothing but the old-style iron latch, large and strong, and fastened in place by turning down a small iron tongue.

It would take much effort to force such a door, but Fred had no doubt any burglar could do it, even though it were ten times as strong. He piled chairs against both, and then made an examination of the windows.

To his consternation, the covered porch extending along the front of the house, passed beneath every window, and was so low that it would be a very easy thing to step from the hypostyle to the entrance.

The room occupied by the ladies was in another part of the building, and much more inaccessible.

Young as Fred Sheldon was, he could not help wondering how it was that where everything was so inviting to burglars they had not visited these credulous and trusting sisters before.

"If that tramp, that I don't believe is a tramp, tries to get into the house he'll do it by one of the windows, for that one is fastened down stairs, and all he has to do is to climb up the portico and crawl in here."

The night was so warm that Fred thought he would smother when he had fastened all the windows down, and he finally compromised by raising one of those at the back of the house, where he was sure there was the least danger of any one entering.

This being done, he sat down in a chair, with the rusty musket in his hand, and began his watch.

From his position he could see the broad, flat candlestick standing on the chest, with the dip already burned so low that it was doubtful whether it could last an hour longer.

"What's the use of that burning, anyway?" he asked himself; "that fellow isn't afraid to come in, and the candle will only serve to show him the way."

Acting under the impulse, he walked softly through the door to where the yellow light was burning, and with one puff extinguished it.

The wick glowed several minutes longer, sending out a strong odor, which pervaded both rooms. Fred watched it until all became darkness, and then he was not sure he had done a wise thing after all.

The trees on both sides of the house were so dense that their leaves shut out nearly all the moonlight which otherwise would have entered the room. Only a few rays came through the window of the other apartment, and these, striking the large, square chest showed its dim outlines, with the phantom-like candlestick on top.

Where Fred himself sat it was dark and gloomy, and his situation, we are sure all will admit, was enough to try the nerves of the strongest man, even if furnished with a good weapon of offence and defence.

"I hope the ladies will sleep," was the unselfish thought of the little hero, "for there isn't any use of their being disturbed when they can't do anything but scream, and a robber don't care for that."

One of the hardest things is to keep awake when exhausted by some unusual effort of the bodily or mental powers, and we all know under how many conditions it is utterly impossible.

The sentinel on the outpost or the watch on deck fights off his drowsiness by steadily pacing back and forth. If he sits down for a few minutes he is sure to succumb.

When Fremont, the pathfinder, was lost with his command in the Rocky Mountains, and was subjected to such arctic rigors in the dead of winter as befell the crew of the Jeannette in the ice-resounding oceans of the far north the professor, who accompanied the expedition for the purpose of making scientific investigations, warned all that their greatest peril lay in yielding to the drowsiness which the extreme cold would be sure to bring upon them. He begged them to resist it with all the energy of their natures, for in no other way could they escape with their lives.

And yet this same professor was the first one of the party to give up and to lie down for his last long sleep, from which it was all Fremont could do to arouse him.

Fred Sheldon felt that everything depended on him, and with the exaggerated fears that come to a youngster at such a time he was sure that if he fell asleep the evil man would enter the room, take all the money and plate and then sacrifice him.

"I could keep awake a week," he muttered, as he tipped his chair back against the wall, so as to rest easier, while he leaned the musket along side of him, in such position that it could be seized at a moment's warning.

The night remained solemn and still. Far in the distance he could hear the flow of the river, and from the forest, less than a mile away, seemed to come a murmur, like the "voice of silence" itself.

Now and then the crowing of a cock was answered by another a long distance off, and occasionally the soft night wind stirred the vegetation surrounding the house.

But among them all was no sound which the excited imagination could torture into such as would be made by a stealthy entrance into the house.

In short, everything was of the nature to induce sleep, and it was not yet ten o'clock when Fred began to wink, very slowly and solemnly, his grasp on the ruined weapon relaxed, his head bobbed forward several times and at last he was asleep.

As his mind had been so intensely occupied by thoughts of burglars and their evil doings, his dreams were naturally of the same unpleasant personages.

In his fancy he was sitting on the treasure-chest, unable to move, while an ogre-like creature climbed into the window, slowly raised an immense club and then brought it down on the head of the boy with a terrific crash.

With an exclamation of terror Fred awoke, and found that he had fallen forward on his face, sprawling on the floor at full length, while the jar tipped the musket over so that it fell across him.

In his dream it had seemed that the burglar was a full hour climbing upon the roof and through the window, and yet the whole vision began and ended during the second or two occupied in falling from his chair.

In the confusion of the moment Fred was sure the man he dreaded was in the room, but when he had got back into the chair he was gratified beyond measure to find his mistake.

"I'm a pretty fellow to keep watch," he muttered, rubbing his eyes; "I don't suppose that I was awake more than a half hour. It must be past midnight, so I've had enough sleep to last me without any more of it before to-morrow night."

He resumed his seat, never more wide awake in all his life. It was not as late as he supposed, but the hour had come when it was all-important that he should keep his senses about him.

Hearing nothing unusual he rose to his feet and walked to the rear window and looked out. It was somewhat cooler and a gentle breeze felt very pleasant on his fevered face. The same stillness held reign, and he moved to the front, where he took a similar view.

So far as could be told, everything was right and he resumed his seat.

But at this juncture Fred was startled by a sound, the meaning of which he well knew.

Some one was trying hard to raise the dining-room window—the rattling being such that there was no mistake about it.

"It's that tramp!" exclaimed the boy, all excitement, stepping softly into the next room and listening at the head of the stairs, "and he's trying the window that he took the nail out of."

The noise continued several minutes—long after the time, indeed, when the tramp must have learned that his trick had been discovered—and then all became still.

This window was the front, and Fred, in the hope of scaring the fellow away, raised the sash, and, leaning out, peered into the darkness and called out:

"Halloo, down there! What do you want?"

As may be supposed, there was no answer, and after waiting a minute or two, Fred concluded to give a warning.

"If I hear anything more of you, I'll try and shoot; I've got a gun here and we're ready for you!"

This threat ought to have frightened an ordinary person away, and the boy was not without a strong hope that it had served that purpose with the tramp whom he dreaded so much.

He thought he could discern his dark figure among the trees, but it was probably fancy, for the gloom was too great for his eyes to be of any use in that respect.

Fred listened a considerable while longer, and then, drawing his head within, said:

"I shouldn't wonder if I had scared him off——"

Just then a soft step roused him, and turning his head, he saw that the very tramp of whom he was thinking and of whom he believed he was happily rid, had entered the room, and was standing within a few feet of him.

CHAPTER V. BRAVE WORK.

When Fred Sheldon turned on his heel and saw the outlines of the tramp in the room behind him he gave a start and exclamation of fear, as the bravest man might have done under the circumstances.

The intruder chuckled and said in his rasping, creaking voice:

"Don't be skeert, young man; if you keep quiet you won't get hurt, but if you go to yelping or making any sort of noise I'll wring your head as if you was a chicken I wanted for dinner."

Fred made no answer to this, when the tramp added, in the same husky undertone, as he stepped forward in a threatening way:

"Do you hear what I said?"

"Yes, sir; I hear you."

"Well, just step back through that door in t'other room and watch me while I look through this chest for a gold ring I lost last week."

Poor Fred was in a terrible state of mind, and, passing softly through the door opening into his bed-room, he paused by the chair where he had sat so long, and then faced toward the tramp, who said, by way of amendment:

"I forgot to say that if you try to climb out of the winder onto the porto rico or to sneak out any way I'll give you a touch of that."

As he spoke he suddenly held up a bull's-eye lantern, which poured a strong stream of light toward the boy. It looked as if he must have lighted it inside the house, and had come into the room with it under his coat.

While he carried this lantern in one hand he held a pistol, shining with polished silver, in the other, and behind the two objects the bearded face loomed up like that of some ogre of darkness.

The scamp did not seem to think this remark required anything in the way of response, and, kneeling before the huge oaken chest, he began his evil work.

For a few moments Fred was so interested that he ceased to reproach himself for having failed to do his duty.

The tramp set the lantern on the floor beside him, so that it threw its beams directly into the room where the boy stood.

The marauder, it must be said, did not act like a professional. One of the burglars who infest society to-day would have made short work with the lock, though it was of the massive and powerful kind, in use many years ago; but this person fumbled and worked a good while without getting it open.

He muttered impatiently to himself several times, and then caught up the bull's-eye, and, bending his head over, carefully examined it, to learn why it resisted his vigorous efforts.

The action of the man seemed to rouse Fred, who, without a moment's thought, stepped backward toward the open window at the rear, the one which had been raised all the time to afford ventilation.

He thought if the dreadful man should object, he could make excuse on account of the warmth of the night.

But the lad moved so softly, or the wicked fellow was so interested in his own work that he did not notice him, for he said nothing, and though Fred could see him no longer he could hear him toiling, with occasional mutterings of anger at his failure to open the chest, which was believed to contain so much valuable silverware and money.

The diverging rays from the dark-lantern still shot through the open door into the bed-room. They made a well-defined path along the floor, quite narrow and not very high, and which, striking the white wall at the opposite side, terminated in one splash of yellow, in which the specks of the whitewash could be plainly seen.

It was as if a great wedge of golden light lay on the floor, with the head against the wall and the tapering point passing through the door and ending at the chest in the other room.

While Fred Sheldon was looking at the curious sight he noticed something in the illuminated path. It would be thought that, in the natural fear of a boy in his situation, he would have felt no interest in it, but, led on by a curiosity which none but a lad feels, he stepped softly forward on tip-toe.

Before he stooped over to pick it up he saw that it was a handsome pocket-knife.

"He has dropped it," was the thought of Fred, who wondered how he came to do it; "anyway I'll hold on to it for awhile."

He quietly shoved it down into his pocket, where his old Barlow knife, his jewsharp, eleven marbles, two slate pencils, a couple of large coppers, some cake crumbs and other trifles nestled, and then, having succeeded so well, he again went softly to the open window at the rear.

Just as he reached it he heard an unusual noise in the smaller apartment where the man was at work, and he was sure the burglar had discovered what he was doing, and was about to punish him.

But the sound was not repeated, and the boy believed the tramp had got the chest open. If such were the fact, he was not likely to think of the youngster in the next room for several minutes more.

Fred was plucky, and the thought instantly came to him that he had a chance to leave the room and give an alarm; but to go to the front and climb out on the roof of the porch would bring him so close to the tramp that discovery would be certain.

At the rear there was nothing by which he could descend to the ground. It was a straight wall, invisible in the darkness and too high for any one to leap. He might hang down from the sill by his hands and then let go, but he was too unfamiliar with the surroundings to make such an attempt.

"Maybe there's a tub of water down there," he said to himself, trying to peer into the gloom; "and I might turn over and strike on my head into it, or it might be the swill barrel, and I wouldn't want to get my head and shoulders wedged into that——"

At that instant something as soft as a feather touched his cheek. The gentle night wind had moved the rustling limbs, so that one of them in swaying only a few inches had reached out, as it were, and kissed the chubby face of the brave little boy.

"Why didn't I think of that?" he asked himself, as he caught hold of the friendly limb. "I can hold on and swing to the ground."

It looked, indeed, as if such a movement was easy. By reaching his hand forward he could follow the limb until it was fully an inch in diameter. That was plenty strong enough to hold his weight.

Glancing around, he saw the same wedge of golden light streaming into the room, and the sounds were such that he was sure the burglar had opened the chest and was helping himself to the riches within.

The next minute Fred bent forward, and, griping the limb with both hands, swung out of the window. All was darkness, and he shut his eyes and held his breath with that peculiar dizzy feeling which comes over one when he cowers before an expected blow on the head.

The sensation was that of rushing into the leaves and undergrowth, and then, feeling himself stopping rather suddenly, he let go.

He alighted upon his feet, the distance being so short that he was scarcely jarred, and he drew a sigh of relief when he realized that his venture had ended so well.

"There," he said to himself, as he adjusted his clothing, "I ain't afraid of him now, I can outrun him if I only have a fair chance, and there's plenty of places where a fellow can hide."

Looking up to the house it was all dark; not a ray from the lantern could be seen, and the sisters were no doubt sleeping as sweetly as they had slept nearly every night for the past three-score years and more.

But Fred understood the value of time too well to stay in the vicinity while the tramp was engaged with his nefarious work above. If the law-breaker was to be caught, it must be done speedily.

But there were no houses near at hand, and it would take fully an hour to bring Archie Jackson, the constable, to the spot.

"The nearest house is Mike Heyland's, the hired man, and I'll go for him."

Filled with this thought, Fred moved softly around to the front, passed through the gate, entered the short lane, and began walking between the rows of trees in the direction of the highway.

An active boy of his age finds his most natural gait to be a trot, and Fred took up that pace.

"It's so dark here under these trees that if there's anything in the road I'll tumble over it, for I never miss——"

"Halloo there, you boy!"

As these startling words fell upon young Sheldon's ear, the figure of a man suddenly stepped out from the denser shadows and halted in front of the affrighted boy, who stopped short, wondering what it meant.

There was nothing in the voice and manner of the stranger, however, which gave confidence to Fred, who quickly rallied, and stepping closer, caught his hand with the confiding faith of childhood.

"O, I'm so glad to see you! I was afraid I'd have to run clear to Tottenville to find somebody."

"What's the matter, my little man?"

"Why, there's a robber in the house back there; he's stealing all the silver and money that belongs to the Misses Perkinpine, and they're sound asleep—just think of it—and he's got a lantern up there and is at work at the chest now, and said he would shoot me if I made any noise or tried to get away, but I catched hold of a limb and swung out the window, and here I am!" exclaimed Fred, stopping short and panting.

"Well now, that's lucky, for I happen to have a good, loaded pistol with me. I'm visiting Mr. Spriggins in Tottenville, and went out fishing this afternoon, but stayed longer than I intended, and was going home across lots when I struck the lane here without knowing exactly where I was; but I'm glad I met you."

"So'm I," exclaimed the gratified Fred; "will you help me catch that tramp?"

"Indeed I will; come on, my little man."

The stranger stepped off briskly, Fred close behind him, and passed through the gate at the front of the old brick house, which looked as dark and still as though no living person had been in it for years.

"Don't make any noise," whispered the elder, turning part way round and raising his finger.

"You needn't be afraid of my doing so," replied the boy, who was sure the caution was unnecessary.

Fred did not notice the fact at the time that the man who had come along so opportunely seemed to be quite familiar with the place, but he walked straight to a rear window, which, despite the care with which it had been fastened down, was found to be raised.

"There's where he went in," whispered Fred's friend, "and there's where we're going after him."

"All right," said Fred, who did not hesitate, although he could not see much prospect of his doing anything. "I'll follow."

The man reached up and catching hold of the sash placed his feet on the sill and stepped softly into the room. Then turning so his figure could be seen plainly in the moonlight, he said in the same guarded voice:

"He may hear me coming, do you, therefore, go round to the front and if he tries to climb down by way of the porch, run round here and let me know. We'll make it hot for him."

This seemed a prudent arrangement, for it may be said, it guarded all points. The man who had just entered would, prevent the thieving tramp from retreating by the path he used in entering, while the sharp eyes of the boy would be quick to discover him the moment he sought to use the front window.

"I guess we've got him," thought Fred, as he took his station by the front porch and looked steadily upward, like one who is studying the appearance of a new comet or some constellation in the heavens; "that man going after him ain't afraid of anything, and he looks strong and big enough to take him by the collar and shake him, just as Mr. McCurtis shakes us boys when he wants to exercise himself."

For several minutes the vigilant Fred was in a flutter of excitement, expecting to hear the report of firearms and the sound of struggling on the floor above.

"I wonder if Miss Annie and Lizzie will wake up when the shooting begins," thought Fred; "I don't suppose they will, for they are so used to sleeping all night that nothing less than a big thunder-storm will start them—but it seems to me it's time that something took place."

Young Sheldon had the natural impatience of youth, and when ten minutes passed without stirring up matters, he thought his friend was too slow in his movements.

Besides, his neck began to ache from looking so steadily upward, so he walked back in the yard some distance, and leaning against a tree, shoved his hands down in his pockets and continued the scrutiny.

This made it more pleasant for a short time only, when he finally struck the happy expedient of lying down on his side and then placing his head upon his hand in such an easy position that the ache vanished at once.

Fifteen more minutes went by, and Fred began to wonder what it all meant. It seemed to him that fully an hour had gone since stationing himself as a watcher, and not the slightest sound had come back to tell him that any living person was in the house.

"There's something wrong about this," he finally exclaimed, springing to his feet; "maybe the tramp got away before I came back; but then, if that's so, why didn't the other fellow find it out long ago?"

Loth to leave his post, Fred moved cautiously among the trees a while longer, and still failing to detect anything that would throw light on the mystery, he suddenly formed a determination, which was a rare one, indeed, for a lad of his years.

"I'll go in and find out for myself!"

Boy-like, having made the resolve, he acted upon it without stopping to think what the cost might be. He was in his bare feet, and it was an easy matter for a little fellow like him to climb through an open window on the first floor without making a noise.

When he got into the room, however, where it was as dark as the darkest midnight he ever saw, things began to appear different, that is so far as anything can be said to appear where it is invisible.

He could see nothing at all, and reaching out his hands, he began shuffling along in that doubting manner which we all use under such circumstances.

He knew that he was in the dining-room, from which it was necessary to pass through a door into the broad hall, and up the stairs to the spare room, where it was expected he would sleep whenever he favored the twin maiden sisters with a visit.

He could find his way there in the dark, but he was afraid of the obstructions in his path.

"I 'spose all the chairs have been set out of the way, 'cause Miss Annie and Lizzie are very particular, and they wouldn't——"

Just then Fred's knee came against a chair, and before he could stop himself, he fell over it with a racket which he was sure would awaken the ladies themselves.

"That must have jarred every window in the house," he gasped, rubbing his knees.

He listened for a minute or two before starting on again, but the same profound stillness reigned. It followed, as a matter of course, that the men up-stairs had heard the tumult, but Fred consoled himself with the belief that it was such a tremendous noise that they would mistake its meaning altogether.

"Any way, I don't mean to fall over any more chairs," muttered the lad, shuffling along with more care, and holding his hands down, so as to detect such an obstruction.

It is hardly necessary to tell what followed. Let any one undertake to make his way across a dark room, without crossing his hands in front and the edge of a door is sure to get between them.

Fred Sheldon received a bump which made him see stars, but after rubbing his forehead for a moment he moved out into the broad hall, where there was no more danger of anything of the kind.

The heavy oaken stairs were of such solid structure that when he placed his foot on the steps they gave back no sound, and he stepped quite briskly to the top without making any noise that could betray his approach.

"I wonder what they thought when I tumbled over the chair," pondered Fred, who began to feel more certain than before that something was amiss.

Reaching out his hands in the dark he found that the door of his own room was wide open, and he walked in without trouble.

As he did so a faint light which entered by the rear window gave him a clear idea of the interior.

With his heart beating very fast Fred tip-toed toward the front until he could look through the open door into the small room where the large oaken chest stood.

By this time the moon was so high that he could see the interior with more distinctness than before.

All was still and deserted; both the men were gone.

"That's queer," muttered the puzzled lad; "if the tramp slipped away, the other man that I met on the road ought to have found it out; but what's become of him?"

Running his hand deep down among the treasures in his trousers pocket, Fred fished out a lucifer match, which he drew on the wall, and, as the tiny twist of flame expanded, he touched it to the wick of the candle that he held above his head.

The sight which met his gaze was a curious one indeed, and held him almost breathless for the time.

The lid of the huge chest was thrown back against the wall, and all that was within it were rumpled sheets of old brown paper, which had no doubt been used as wrappings for the pieces of the silver tea-service.

On the floor beside the chest was a large pocket-book, wrong side out. This, doubtless, had once held the money belonging to the old ladies, but it held it no longer.

Money and silverware were gone!

"The tramp got away while we were down the lane," said Fred, as he stood looking at the signs of ruin about him; "but why didn't my friend let me know about it, and where is he?"

Fred Sheldon stopped in dismay, for just then the whole truth came upon him like a flash.

These two men were partners, and the man in the lane was on the watch to see that no strangers approached without the alarm being given to the one inside the house.

"Why didn't I think of that?" mentally exclaimed the boy, so overcome that he dropped into a chair, helpless and weak, holding the candle in hand.

It is easy to see how natural it was for a lad of his age to be deceived as was Fred Sheldon, who never in all his life had been placed in such a trying position.

He sat for several minutes looking at the open chest, which seemed to speak so eloquently of the wrong it had suffered, and then he reproached himself for having failed so completely in doing his duty.

"I can't see anything I've done," he thought, "which could have been of any good, while there was plenty of chances to make some use of myself if I had any sense about me."

Indeed there did appear to be some justice in the self-reproach of the lad, who added in the same vein:

"I knew, the minute he stopped to ask questions at our front gate, that he meant to come here and rob the house, and I ought to have started right off for Constable Jackson, without running to tell the folks. Then they laughed at me and I thought I was mistaken, even after I had seen him peeping through the window. When he was eating his supper I was sure of it, and then I should have slipped away and got somebody else here to help watch, but we didn't have anything to shoot with, and when I tried to keep guard I fell asleep, and when I woke up I was simple enough to think there was only one way of his coming into the house, and, while I had my eye on that, he walked right in behind me."

Then, as Fred recalled his meeting with the second party in the lane, he heaved a great sigh.

"Well, I'm the biggest blockhead in the country—that's all—and I hope I won't have to tell anybody the whole story. Halloo!"

Just then he happened to think of the pocket-knife he had picked up on the floor, and he drew it out of his pocket. Boy-like, his eyes sparkled with pleasure when they rested on the implement so indispensable to every youngster, and which was much the finest one he had ever had in his hand.

The handle was pearl and the two blades were of the finest steel and almost as keen as a razor.

Fred set the candle on a chair, and leaning over, carefully examined the knife, which seemed to grow in beauty the more he handled it.

"The man that dropped that is the one who stole all the silverware and money, and there's the letters of his name," added the boy.

True enough. On the little piece of brass on the side of the handle were roughly cut the letters, "N. H. H."

CHAPTER VI. ON THE OUTSIDE.

When Fred Sheldon had spent some minutes examining the knife he had picked up from the floor, he opened and closed the blades several times, and finally dropped it into his pocket, running his hand to the bottom to make sure there was no hole through which the precious implement might be lost.

"I think that knife is worth about a thousand dollars," he said, with a great sigh; "and if Aunt Lizzie and Annie don't get their silverware and money back, why they can hold on to the jack-knife."

At this juncture it struck the lad as a very strange thing that the two ladies should sleep in one part of the house and leave their valuables in another. It would have been more consistent if they had kept the chest in their own sleeping apartment, but they were very peculiar in some respects, and there was no accounting for many things they did.

"Maybe they went in there!" suddenly exclaimed Fred, referring to the tramp and his friend. "They must have thought it likely there was something in their bed-room worth hunting for. I'll see."

He felt faint at heart at the thought that the good ladies had been molested while they lay unconscious in bed, but he pushed his way through the house, candle in hand, with the real bravery which was a part of his nature.

His heart was throbbing rapidly when he reached the door of their apartment and softly raised the latch.

But it was fastened from within, and when he listened he distinctly heard the low, gentle breathing of the good souls who had slumbered so quietly all through these exciting scenes.

"I am so thankful they haven't been disturbed," said Fred, making his way back to his own room, where he blew out his light, said his prayers and jumped into bed.

Despite the stirring experiences through which he had passed, and the chagrin he felt over his stupidity, Fred soon dropped into a sound slumber, which lasted until the sun shone through the window.

Even then it was broken by the gentle voice of Aunt Lizzie, as she was sometimes called, sounding from the foot of the stairs.

Fred was dressed and down in a twinkling, and in the rushing, headlong, helter-skelter fashion of youngsters of his age, he told the story of the robbery that had been committed during the night.

The old ladies listened quietly, but the news was exciting, indeed, and when Aunt Lizzie, the mildest soul that ever lived, said:

"I hope you are mistaken, Fred; after breakfast we'll go up-stairs and see for ourselves."

"I shall see now," said her sister Annie, starting up the steps, followed by Fred and the other.

There they quickly learned the whole truth. Eight hundred and odd dollars were in the pocketbook, and the intrinsic worth of the silver tea service amounted to fully three times as much, while ten times that sum would not have persuaded the ladies to part with it.

They were thrown into dismay by the loss, which grew upon them as they reflected over it.

"Why didn't you call us?" asked the white-faced Aunt Lizzie.

"Why, what would you have done if I had called you?" asked Fred, in turn.

"We would have talked with them and shown them what a wicked thing they were doing, and reminded them how unlawful and wrong it is to pick a lock and steal things."

"Gracious alive! if I had undertaken to call you that first man would have shot me, and it was lucky he didn't see me when I swung out the back window; but they left something behind them which I'd rather have than all your silver," said Fred.