The Flying Boys in the Sky

Edward S. Ellis

THE FLYING BOYS IN THE SKY

Timely and fascinating stories of adventure in the air, accurate in detail and intensely interesting in narration.

The Flying Boys Series is bound in uniform style of cloth with side and back stamped with new and appropriate design in colors. Illustrated by Edwin J. Prittie.

Price, single volume $0.60 Price, per set of two volumes, in attractive box $1.20

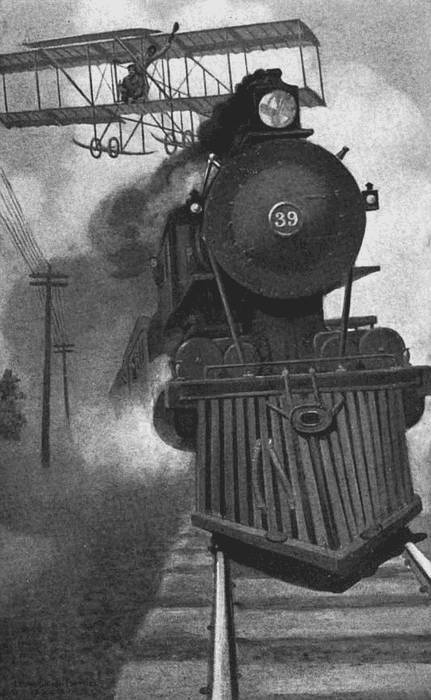

The Biplane Forged Bravely Ahead.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Learning to Fly | 9 |

| II. | Bohunkus Johnson | 18 |

| III. | The Aeroplane in a Race | 27 |

| IV. | Trying for Altitude | 36 |

| V. | A Woodland Expert | 45 |

| VI. | Working for Dinner | 54 |

| VII. | The Dragon of the Skies | 63 |

| VIII. | The Professor Talks on Aviation | 72 |

| IX. | The Professor Talks on Aviation (Continued) | 79 |

| X. | The Flying Boys Continue Their Journey | 90 |

| XI. | Fired On | 98 |

| XII. | Peaceful Overtures Fail | 107 |

| XIII. | Science Wins | 117 |

| XIV. | Milo Morgan Saves the Day | 125 |

| XV. | Uncle Tommy | 134 |

| XVI. | A Mysterious Communication | 143 |

| XVII. | Called to the Rescue | 152 |

| XVIII. | Planning the Search | 161 |

| XIX. | The Aeroplane Destroyed | 170 |

| XX. | A Puzzling Telegram | 179 |

| XXI. | Beginning the Search | 188 |

| XXII. | In Danger of Collision | 197 |

| XXIII. | The Cabin in the Woods | 206 |

| XXIV. | On the Trail of the Backhanders | 215 |

| XXV. | A False Clue | 224 |

| XXVI. | The Search Renewed | 233 |

| XXVII. | Bohunkus at the Levers | 242 |

| XXVIII. | Fired on by the Kidnappers | 251 |

| XXIX. | Retribution | 260 |

| XXX. | The Rescue | 269 |

| XXXI. | Lynch Law | 278 |

| XXXII. | Mysteries are Explained | 288 |

| XXXIII. | Where is Bohunkus? | 297 |

| The Biplane Forged Bravely Ahead | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| A Fanlike Stream of Light Shot Out | 64 |

| In the Center Stood a Log Cabin | 194 |

| The Bomb Had Exploded With Terrific Force | 262 |

CHAPTER I.

LEARNING TO FLY.

One mild summer morning in 1910, Ostrom Sperbeck, a professional aviator, stood on the edge of a broad meadow belonging to the merchant, Gabriel Hamilton, closely watching the actions of Harvey Hamilton, the seventeen-year-old son of his friend, to whom the lithe, smooth-faced German was giving his first lessons in flying an aeroplane.

It was on the return voyage from Naples to New York of the Italian steamer Duca degli Abruzzi, that Mr. Hamilton and his boy made the acquaintance of the genial foreigner, who was on his way to the United States to take part as a competitor in several of the advertised meets in different parts of the country. The acquaintance thus begun ripened into a strong friendship and the Professor became the guest of the merchant, who was a commuter between his country residence and the metropolis.

The youth, like thousands of American boys, was keenly interested in the art of flying in the air, and the Professor was glad to undertake to give him instruction. The two went by train to Garden City, Long Island, where the elder found his new Farman biplane awaiting his arrival. Harvey mounted to the aluminum seat in front of the gasoline tank and engine, while his conductor placed himself a little below him in front, where his limbs had free play. The machine was pointed to the southwest and Harvey enjoyed to the full his first ride above the earth. His attention was divided between the wonderful moving panorama below and studying every action of the expert, who was as much at home on his elevated perch as when seated in the smoking room of the Duca degli Abruzzi, chatting with his friends. He noted the movements of the feet which controlled the vertical rudder at the rear, and the lever beside which the Professor sat and elevated or depressed the horizontal rudder on the outrigger in front, thus directing the ascent and descent of the machine.

A thrilling surprise awaited Harvey when, after two stops on the way for renewing the gasoline and oil, they reached the merchant’s home. Professor Sperbeck wished to make a preliminary tour through the country which he had now visited for the first time, and he left his order at Garden City for the construction of a new biplane. The one that had been finished was sold to Mr. Hamilton, who made a birthday present of it to his son, it being a question as to who was the more pleased, Harvey or his parent.

Omitting other preliminaries for the present, let us return to the smooth, sloping meadow where under the eye of the German expert, the young aviator was receiving his first instruction in the fascinating diversion.

“I know that you did not let an action of mine elude you,” said the Professor, “and you feel that you understand pretty much all.”

Standing by the biplane, the smiling Harvey nodded his head.

“I have a dim suspicion in that direction.”

“You can never make yourself an aviator without self-confidence, but you may have too much of it. In that case you become reckless and bad results are certain to follow. Nor can you learn by simply observing the conduct of another. You have a motto in your country about experience.”

“It is Benjamin Franklin’s,—‘Experience keeps a dear school but fools will learn in no other,’” said Harvey, atremble with eagerness.

“Quite true; well, if you please, you may seat yourself.”

The lad stepped forward and sat down, his feet resting on the cross lever below, while he grasped the upright control lever on his right.

“Suppose you wish to leave the ground and mount into the air?”

“I pull this lever back; the motion turns up the horizontal rudder out there in front and the auxiliary elevating rudder in the rear; when I have gone as high as I wish, I hold the rudder level, and when I wish to descend, I dip it downward.”

“Nothing could be more simple; and when you desire to change your direction to the right or left?”

“I work this lever with my feet, as we do in tobogganing.”

“You have two smaller levers on the left.”

“They control the spark and throttle.”

“We won’t enter further into the construction of the machine at present. I am sure you were born to be a successful aviator.”

The quiet assurance of these words vastly strengthened the confidence of Harvey Hamilton. He knew the Professor believed what he said, and who could be more capable of correct judgment? Then, as if fearing he had infused too much courage into the youth, the instructor added:

“So far everything seems easy and simple. We were fortunate on our way here, in having the most favorable weather conditions, but you are sure sooner or later to run into complex conditions. Columns of cold air are forever pressing downward and warm ones pushing upward. This constant conflict creates air holes and all sorts of twists and gyrations that play the mischief with aviators, unless they know all about them.

“You have seated yourself, but don’t try to start till I give the word. I wish first to put you through a little drill. I shall call certain conditions and you must do the right thing on the instant. Are you ready?”

“Fire away,” replied Harvey, on edge in his expectancy.

“Ascend!”

Like a flash the youth pulled the control lever back.

“Too far; lessen the angle.”

He promptly obeyed.

“Volplane!”

Harvey pushed the lever forward, but not too far.

“Quite well; go to the right.”

The youth started to shift the rear rudder with his feet and smiled.

“That is hard work.”

“Why?”

“Because of the gyroscopic action of the propeller; it is much better to turn to the left, though I suppose one can manage a long turn to the right.”

“The Wright brothers have no trouble in swinging that way.”

“Because they use two propellers, revolving in opposite directions, thus neutralizing that gyroscope business.”

“You are tipping to the left!” shouted the Professor.

On the instant the aviator swung the control lever to the right.

“You are caught in a fierce tempest.”

Since Harvey could not well make the right evolution he replied:

“I should dive into it.”

“That’s right; never run away from a maelstrom. I suppose you feel competent to make a voyage through the air?”

“I don’t see why I cannot,” replied Harvey; “I studied everything you did on our way from Garden City and I think I know what to do in any emergency.”

“Admitting that that is possible—which it isn’t—it is all-important that before you leave the earth you should get acquainted with your machine.”

“Ask me about its parts and see whether I am not.”

“That isn’t what I mean; you got that information from the answers to my inquiries at the factory at Garden City, which I asked for your benefit. You must be as familiar with the aeroplane as with your pony which you have ridden for years and feel as much at home in your seat as if you had occupied it for months. It will take time to acquire that knowledge.”

“I am at home now,” replied Harvey, who could not help thinking his friend was over-cautious.

“Your danger is of having too much self-confidence. Remember and do exactly what I tell you to do and nothing else.”

The pupil assured his instructor of the strictest obedience.

“Very well.”

The Professor stepped to the rear, grasped a blade of the propeller and gave it a vigorous swing. That set the motor going with its deafening racket, but it was so throttled that the machine stood still for a minute or two, Sperbeck holding back all he could with one hand until the pressure became too great to resist. Then the aeroplane began moving forward, with fast increasing speed. When it had traveled a hundred yards, Harvey grasped the lever ready to point the front rudder upward upon receiving the order from the Professor. The noise of the motor would have drowned the loudest voice, and the youth kept glancing around for the expected signal. But it was not made. Instead, the Professor motioned with one hand for him to circle to the left. Harvey was disappointed but did not hesitate for an instant. He came lumbering and lurching over the sward, and, shutting off the motor, halted a few paces in front of his instructor, who had lighted a cigarette.

“It is best to cut grass for two or three days,” explained the teacher.

“It surely will not take that long,” replied Harvey in dismay.

“I trust not, but no ascent will be attempted to-day.”

Harvey forced himself to smile, though he made a comical grimace.

“Put me through the paces; I’m bound to learn this business or break a trace.”

Several spectators had gathered on the edge of the field and were watching the actions of the two with the aeroplane. They would have come nearer had not Harvey warned them by a gesture not to do so. He did not mind their enjoying the sight, for they could do that when a little way off as well as if closer, but they were likely to get in his way, and hinder matters.

Again and again the biplane went awkwardly forward on its three small wheels with their rubber tires. The field contained ten or twelve acres, thus giving plenty of space for maneuvering. Once he came within a hair of running into the fence, because as it seemed to him the machine did not respond with its usual promptness, but he showed rapid improvement and the Professor complimented him on his success.

“I’m playing the part of a navigator of a prairie schooner,” said the youth, “though they are drawn by animals instead of being propelled by wind. I suppose, Professor, that before the summer is over you will let me try my wings?”

“That depends upon how well you get on with your first lessons.”

CHAPTER II.

BOHUNKUS JOHNSON.

Suddenly a shout came from the edge of the field, and a negro lad vaulted over the fence and ran toward the couple. As he drew near he called:

“Why didn’t yo’ tole me ’bout dis, Harv?”

“I did call at your house for you, but Mr. Hartley said you were asleep.”

“What ob dat? Why didn’t yo’ frow a brick fru de winder and woke me up? Gee! What hab yo’ been trying to do, Harv?”

The newcomer was about the same age as Harvey Hamilton, but taller, broader and larger every way. He was the “bound boy” of a neighbor and had been a playmate of the white youth from early childhood. He was as much interested in aviation as Harvey, and had been trying to build an air machine for himself, or rather helping his friend to construct one, but their failure was so discouraging that they gave it up. What was the sense of attempting such a task when Mr. Hamilton stepped in and bought one of the best of aeroplanes for his son?

Professor Sperbeck had met Bohunkus Johnson, being first attracted by his odd name and then by the willingness and good nature of the colored youth. Bunk, as he was generally called by his acquaintances, was much disappointed because he had not been present earlier, but no one was to blame except himself. Shoving his hands in his pockets, he walked about the aeroplane, which he had admired upon its arrival, inspecting and trying to understand its workings.

“Hab yo’ flowed?” he asked, abruptly halting and looking at Harvey who retained his seat.

“Not yet.”

“Why doan’ yo’ do so? What’s de use ob fooling round here?”

“Professor Sperbeck thinks I should learn more before leaving the ground. How would you like to try your hand?”

Bohunkus took off his cap and scratched his head.

“I guess I’ll watch yo’ frow flipflaps awhile.”

Harvey turned to the Professor, who shook his head.

“You don’t wish to smash the biplane so soon. You will have enough tumbles without his help. If you are ready you may try it again.”

By this time Harvey had become somewhat accustomed to the sensitiveness of the machine. It required slighter movements of the lever than he had supposed and the response was sometimes quicker than he expected. He understood what his instructor meant by insisting that an aviator should become familiar with his machine.

Bohunkus was asked to hold the rear of the aeroplane until the revolving propeller acquired more velocity. The dusky youth buried his heels in the dirt and held the framework with might and main. The pull rapidly increased, while he put forth all his strength, which was considerable. The Professor gave no help, but trying to keep his face straight, watched things. Despite all he could do, Bunk was compelled to yield a few inches. He still resisted desperately, but while he could not add to his power, the uproarious motor fast did so. Suddenly it made a bound forward, and Bunk sprawled on his face, with his cap flying off. His hold had slipped and the machine shot forward with a speed far greater than any one of the three could have reached.

“Hang de ole thing!” exclaimed Bunk, climbing to his feet and brushing the dust from his clothes; “what’s de use ob it yanking a feller like dat?”

The roaring motor was too near for either of his friends to understand his words, but it was easy to imagine their substance.

When Harvey had completed his circuit of the field, Bunk asked that he might try his hand. He certainly was not lacking in assurance, but the Professor would not consent.

“You might do well, but the chances are you would not. You will get your chance after a time. You may ride with Harvey if you wish.”

With some hesitation, Bunk climbed into the seat behind his friend.

“Am yo’ gwine to go up?” he asked.

“Not at present. Why do you wish to know?”

“So I can jump if yo’ don’t manage things right.”

He grasped one of the supports on either side and braced himself. Naturally he was timid, but it did not seem to him there could be much danger so long as they remained on the ground. Half way round the field, his self-confidence returned, and his dark face was lighted with a broad grin as the machine came to a stop near where the Professor was waiting.

“Why can’t yo’ fly fru de air by staying on de ground?” was the next bright question of Bohunkus; “dat would be as nice as habin’ Christmas come on de fourth ob July, so yo’ could slide down hill barefoot.”

“Suppose I relieve you for awhile,” suggested the instructor. Harvey sprang to the ground and Mr. Sperbeck took his place, indicating, when Bohunkus started to leave his seat, that he should remain.

A few minutes later, the negro received the shock of his life. The Professor allowed the aeroplane to rush over the ground until its speed must have been forty miles an hour. Then he pulled back the lever and it instantly began mounting into the air. Bohunkus did not comprehend what was going on until he was fifty feet aloft and still ascending.

He threw his head to one side and stared at the ground, which appeared to be rushing away from him with dizzying swiftness. For an instant he meditated leaping overboard and catching the earth before it got beyond his reach. He partly rose to his feet, but the distance was too great. He called to the Professor:

“Stop! I doan’ feel well; let me git down. What’s de use ob such foolishness?”

But there was too much uproar for the aviator to hear, and had he caught the words he would have given no attention. Bohunkus in his affright glanced across the field to where Harvey Hamilton was standing with his gaze on the machine. Harvey waved his hand and the simple act did much to bring back the courage of the negro.

“I guess I can stand it as well as him,” was his reflection; “so go ahead.”

The course of Professor Sperbeck might well give the youth a calmness which he could not have felt in other circumstances. He skimmed several miles over the country, rising five or six hundred feet in the air, and attaining a velocity of fifty miles an hour. He had been pleased with the aeroplane on the ride from Garden City, and was still more pleased upon trying it out again. It seemed to have gained a steadiness and sureness which it lacked before.

As has been said, the real test of an aviator’s skill is not in sailing through the air where all is tranquil, but in starting and in landing. Professor Sperbeck had left the ground without the least difficulty and he now came down with the grace and lightness of a bird.

In the afternoon Harvey Hamilton resumed his lessons, the instructor complimenting his proficiency.

“If the conditions are favorable to-morrow, we shall leave the ground with you at the helm,” he assured his pupil, when they gave over the attempts for the day. At the side of the field nearest the house, Mr. Hamilton had had a hangar built into which the aeroplane was run and the door carefully locked. It was natural that the neighbors should show much curiosity in the contrivance, and there was no saying what mischief they might do. Bohunkus felt so much concern on this point that he came over to his friend’s home after the evening meal and joined them on the porch, where Mr. Hamilton was also seated.

“I think,” said Bunk, “that we hadn’t oughter leave dat airyplane by itself.”

“We haven’t,” replied Harvey; “the building is strong and the door locked.”

“But some folks mought bust off de lock and run off wid it; some ob dem people am mighty jealous ob me and yo’, Harv.”

“They are all good friends of ours,” remarked the merchant; “I’m sure nothing is to be feared from them.”

“I hopes not, but I feels oneasy.”

“What would you suggest?”

“Dat some one keeps watch all night.”

“Suppose you do it?”

“I’ll take my turn wid Harv.”

“Very well; when the night is a little farther along, Bunk, you may go out there and stand guard till say about midnight; then come to the house and wake up Harvey, and he will take his turn at playing sentinel.”

“That soots me,” Bunk was quick to say, knowing it would be much easier to keep awake during the first half of the night. So, while the others chatted as the evening wore on, the colored youth rose, yawned, stretched his arms and announced that he would go to his home not far off, tell Mr. Hartley and his wife of the arrangement and then assume his duties at the hangar.

Although he saw no call for all this extra care, Harvey was quite willing to divide the duty with his colored friend, but he meant that Bunk should come to the house and rouse him, for he could not be expected to stay awake. However, the young aviator dreamed so much of flying through the air, and was so absorbed with the entrancing scheme, that he was the first one to wake in his home. He sprang out of bed, as the sun was creeping up the horizon, and lost no time in hurrying out to the hangar to learn why Bohunkus had not called him, though he held a strong suspicion of the real reason.

As Harvey sped around the corner of the low, flat structure, the first object upon which his eyes rested was Bohunkus, stretched out on his back, his mouth open, and breathing loudly, as no doubt he had been doing through most of the night. Harvey left him lying where he was, and rejoined his folks with the story of what he had seen.

An hour later, Professor Sperbeck, accompanied by the merchant and Harvey, walked to the hangar to resume the instruction of the previous day. In the interval, Bohunkus had awakened and gone for his breakfast. He said nothing of his remissness and his friends did not refer to it, since they had more serious matters to hold their attention.

Mr. Hamilton was much pleased with the proficiency shown by his son, but did not stay long, since important business called him to the city. The day was a busy one for the young aviator, who was allowed to make a flight in the afternoon with the watchful Professor seated behind him. He had very few suggestions to make.

When Harvey came down to earth, he bumped rather energetically, but no harm was done, and on the third trial no criticism was made. Two more days were spent in practice and then the instructor said:

“You are prepared to make as long a voyage through the air as you wish, and without any assistance from me.”

CHAPTER III.

THE AEROPLANE IN A RACE.

The barograph showed that the aeroplane was more than nine hundred feet above the earth and the anemometer, or small wind wheel, indicated that the speed was forty-odd miles an hour, with the propeller making a thousand revolutions a minute. It was capable of increasing that rate by twenty per cent. and the aviator was gradually forcing it to do so.

The youth who sat in front, with the long control lever in his right hand, was our friend Harvey Hamilton, who, under the instruction of Professor Ostrom Sperbeck, the German aviator, had become so expert that he felt equal to any emergency that was likely to occur during his aerial excursions. The small levers on his left, governed as we remember the spark and throttle, while the vertical rudders were operated by the feet. So long as the heavens remained calm or only moderate breezes were encountered, everything would go as smoothly as if he were treading firm ground, but there was no saying what troubles were likely to arise,—some of them with the suddenness of a bolt from the blue.

Harvey had his back to the tank, which held ten gallons of gasoline, or petrol as it is called on the other side of the ocean, and two gallons of oil, one being as indispensable as the other.

In the aluminum seat just in front of the tank was Harvey’s passenger, the support being adjustable and capable of carrying two persons without threatening the center of gravity, provided care was used. This passenger has already been introduced to you under the name of Bohunkus Johnson, who was the bound boy of a neighboring farmer, Mr. Cecil Hartley. He was a favorite with his easy-going master, who sent him to the district school during winter and let him do about as he pleased at other times. He had picked up the simplest rudiments of a primary education and with the expenditure of a good deal of labor could write, though he scorned to pay any attention to so unimportant a matter as spelling.

Bunk and Harvey being of the same age, were playmates from earliest childhood. The fact that they were of different races had no effect upon their mutual regard. Being the son of a wealthy merchant, the white youth was able to do many favors for his dusky comrade, who, bigger and stronger, would have risked his life at any time for him.

Although this particular flight was made on a sultry summer afternoon, each lad wore thick clothing and a cap specially made for aviators, as a protection against wind and cold. The first intention of Harvey was to climb high enough in the sky to establish a record for himself that would make all other rivals green with envy.

But not yet. There was too much fascination in coddling to the earth, where the wonderful varied panorama was ever changing, and always of entrancing novelty and beauty.

Bohunkus having little to do except use his eyes enjoyed the visual feast to the full. At the beginning he studied the action of Harvey, seated at his feet, having in view that thrilling hour when he would be permitted to handle the levers and guide the airship through space himself.

“I can do it as well as him,” he said to himself; “de machine sets on its three little wheels wid dere rubber tires, and de propeller am started so fast dat yo’ can’t see de paddles spin round; den dem dat am holding de same lets go and it runs ’bout fifty yards, like lightnin’; den Harvey pulls de big lever back and dat flat rudder out front am turned upward and de ting springs into de air like a scared bird and dere yo’ am!”

As Bohunkus sat he grasped a bit of the framework on his right and a corresponding support on his left. This was not always necessary, for it was smooth sailing, but, as has been intimated, there was no saying when a sudden squall or invisible pocket or hole in the wind would shake things up, and force one to hold on for dear life. He leaned slightly forward and looked down at the world sweeping under him. They were skimming over a village, numbering barely a score of buildings, the only noticeable one being the white church with its tapering spire pointing toward the realm to which erring men were directed. Just beyond the dusty winding road disappeared into a wood a mile in extent, emerging on the other side and weaving through the open country until it could no longer be traced.

The river far to the left suggested a ribbon of silver, so small that several tiny sails creeping over it appeared to be standing still. To the right and front a large city was coming into clearer view. The spires, skyscrapers and tall buildings were a vast jumble in which he could identify nothing. He did not attempt even to guess the name of the place.

A railway train was just leaving the village below them on its way to the city in the distance. The youths saw the white puff of steam from the whistle, which signalled its starting, and the black belchings of smoke came faster and faster as the engine rapidly gained headway. Harvey slightly advanced the lever and the aeroplane began descending a little way in front of the train. The contestants in this novel race should be nearer each other to prevent any mistake and make the contest more exhilarating.

Two hundred feet from the ground, Harvey pulled back the lever and the flat rudder on the front outrigger became horizontal. The downward dip of the machine ceased and with a graceful curve glided forward on a level course. No professional could have executed the maneuver with more precision. Harvey during these few moments decreased the revolutions of the propeller so as not to draw away from the locomotive. The race should be a fair one, even if the result was not in doubt.

This lagging caused the biplane to fall somewhat to the rear and gave the train time to hit up its pace. The engineer and fireman had caught sight of the machine some minutes before, and eagerly accepted the challenge. Both were leaning out of the cab windows and the engineer waved his hand at the contestant aloft. The fireman swung his greasy cap and shouted something which of course the youths were unable to catch. The passengers had learned what was in the wind, and crowded the platforms and thrust their heads from the windows, all saluting the aviator and intensely interested in the struggle for mastery.

Harvey was too occupied with the machine to give much attention to anything else. He knew he could rely upon Bohunkus for all that was due in that line. The dusky youth was so wrought up that he came startlingly near unseating himself more than once. He leaned far over, circled his cap about his head and shouted and whooped and kicked out his feet with delight. The laughing passengers who stared into the sky, saw the black face with its dancing eyes, bisected by an enormous grin, which displayed the rows of perfect even teeth, and all learned what a perfectly happy African looks like.

Jim Halpine, the engineer, said grimly to his fireman:

“I’ve heard about their flying faster than anything can travel over the ground, but I’ll teach that fellow a lesson. Old 39 can make a mile a minute as easy as rolling off a log; watch me walk away from him.”

He “linked her up” by drawing the reversing lever back until it stood nearly on the center and dropped the catch in place. Then the puffs came faster and faster, and not so loud, and 39 rapidly rose to her best pace. Having done all he could in that direction, Jim kept his left hand on the throttle lever, and divided his attention between peering out at the track in front and glancing upward at the curious contrivance that was coursing through the air just above him. The fact that it was creeping up caused no misgiving, for that was manifestly due to the fact that he himself had not yet acquired full headway.

Harvey meant to get all the fun possible out of the race. He was certain he could beat the engine, but to do so “off the reel” would spoil the enjoyment. He would dally for a time and when defeat seemed impending, would dart ahead—always provided he should be able to do so.

The locomotive had a straight away run of seven or eight miles, when it would have to slow down for the city it was approaching. The race therefore must be decided within the next ten minutes.

Harvey Hamilton played his part well. The engine and train being directly under him, his view of them was perfect without detracting from the necessary attention to his biplane. He was just behind the last car when he knew from the appearance of things that the engineer had struck his highest pace. The youth speeded up the motor so as slightly to add to the propeller’s revolutions, but he showed no gain in swiftness. He was only holding his place.

The shouting passengers shouted still more, if that could be possible, and called all sorts of tantalizing cries:

“Throw down your rope and we’ll give you a tow.” “Get out and run alongside of us!” “You ain’t racing with a cow.” “We’re going some!”

Such and similar were the good-natured taunts, which produced no effect upon the aviators for they did not hear them. The most exasperating gesture was that of Jim Halpine the engineer, who leaned far out of his cab and gently beckoned to the youths to come forward and keep him company. The fireman stood between the cab and tender and imitated his chief.

Harvey Hamilton seemed to see and hear them not. Bending far over with the lever grasped, he acted as if trying to add to his speed by the pose, as a person in his situation will sometimes do unconsciously. His face was drawn, as if with tense anxiety, and there was not the shadow of a smile upon it. All the same he was chuckling inwardly.

Bohunkus Johnson was almost beside himself. At first he did not doubt that a crushing triumph would speedily come to him and his companion, but as the seconds flew by and there was no gain upon the train thundering over the rails, a pang of doubt crept over him.

“Go it, Harv! Put on more steam! What’s de matter wid yo’?” he shouted, swinging his arms and hitching forward as if to add an impulse to their progress. “If yo’ lose dis race I’ll jump overboard and swim to land. Dem folks see me blushing now!”

Less than a minute later, the African shouted to unhearing ears:

“Glory be! Dat’s de talk! Now we’ve got ’em!”

The aeroplane was overtaking the train. Though the gain was slow it was unmistakable.

CHAPTER IV.

TRYING FOR ALTITUDE.

Ah, but Harvey Hamilton was sly. He began slowly creeping up until his machine was directly over the rear passenger coach, there being three beside the express car. Had he dropped a stone from his perch, it would have fallen upon the roof of the last one. The exultant expression on the myriad of faces took on a tint of anxiety. The fireman yanked open the door of the fire-box and shoveled in coal. No need of that, for 39 was already blowing off, even when running at so high speed. Jim Halpine had drawn over the long reversing lever till it stood within a few inches of perpendicular and another shift would have choked the engine.

The young aviator held his place for a brief while and then began gradually drifting back again. Bohunkus Johnson groaned.

“Confound it! what’s de use ob trying to be good?” he wailed; “dem folks will grin dere heads off. Harv! make tings hum!”

Heedless of him, Harvey was carrying out his own scheme. He saw that the game was his and he was playing with the locomotive. When gaining on it, the airship was not doing its best, and his slight retrogression was in order to make his victory more impressive. Each contestant was going fully sixty miles an hour. No. 39 could do no more, but the aeroplane had not yet extended herself. She now proceeded to do so, inasmuch as in the circumstances the struggle must soon terminate.

Having dropped well to the rear again, Harvey called upon the motor to do its best. Its humming took on the character of a musical tone, and the propeller spun around, twelve hundred revolutions to the minute. The keenest eye could detect nothing of the ends of the blades, and only faintly discern them nearer the shaft, as if they were so much mist.

And then the biplane forged bravely ahead. She moved steadily along over the roofs of the cars, one after the other, and pulled away from the engine whose ponderous drivers appeared to be spinning around with the dizzying swiftness of the propeller overhead. Jim Halpine was utilizing every ounce of power, but could do no more, for he was already doing his best. It humiliated him to be thus left behind, but there was no help for it. In his chagrin he tried a little trick which deceived no one, not even the two victors. Pretending he detected something amiss on the rails, he emitted a couple of blasts from his whistle and shut off steam. It looked as if he was actuated by prudence, but the obstruction was imaginary.

Most of the passengers like true sportsmen cheered the winner. Even the grinning fireman circled his cap again about his tousled head, but the engineer was glum and acted as if the only thing in the world of interest to him was the rails stretching away in front. What did he care for airships bobbing overhead? They were only toys and could never amount to anything in the economy of life.

As for Bohunkus Johnson he could not contain himself. Harvey remained as calm as a veteran, and gave no attention to anything except his machine, but his companion stood up in the hurricane at the imminent risk of playing the mischief with the aeroplane’s center of gravity, waved his cap and furiously beckoned the engineer not to lag behind. His thick lips could be seen contorting themselves and evidently he was saying something. Had the laughing passengers been able to catch his words—which they were not—they would have heard something like the following:

“Why doan’ yo’ trabel? Yo’s only walking; we ain’t half trying; can’t yo’ put on more steam and make us show what we can do? I’m plum disgusted wid yo’.”

Harvey Hamilton did not speak. He was “letting out” the machine. He meant to learn what it could do. When several hundred yards ahead of the train, he lifted the lip of the rudder in front, and the structure glided upward until he was a quarter of a mile above the earth. Even then Bohunkus behaved so extravagantly that the aviator turned his head and motioned to him to cease.

“Can’t doot, Harv! My mouf am so wide open dat it’ll take me a good while to bring my jaws togeder agin, and I’m ready to tumble out head fust.”

By and by the colored youth toned down enough to resume his seat and check his explosions of delight, though he looked around and waved his hand several times at the train which was now so far to the rear that his action was not understood.

“Gee! but it’s getting cold!” he exclaimed some minutes later, with a shiver. He buttoned his thick coat to the chin, donned his mittens, and wondered what it all meant. He had never understood, though he had been told more than once, that temperature decreases with increasing altitude. He had objected to donning such thick garments when about to start on their flight, but Harvey was the boss and insisted.

Bohunkus’s next surprise came when he looked between his feet. They were directly over the city noticed some time before, but the buildings were shrunken and mixed together in a way that even he understood.

The anemometer suspended at the side of Harvey Hamilton showed that the aeroplane was coursing through the air at the rate of not quite a mile a minute. With the low temperature caused by the altitude, the wind created in the still atmosphere cut the faces of the two like a knife, and even penetrated their thick clothing. Bohunkus turned up his coat collar, and drew his cap over his ears, but his feet ached. He hoped the aviator would soon strike milder weather, though the colored youth did not know whether it was to be sought for above or below.

“If it gits colder as yo’ go up,” he reflected between his chattering teeth, “it must be orful cold when yo’ reach heben; I remember now dat I was tole something ’bout dat, but I thought dey was fooling me.”

The front rudder still sloped upward, and Harvey showed no intention of dropping lower or even of maintaining the level already reached. He and his companion had started on a week or ten days’ outing, and it struck him that now was as good a time as he was likely to have for making a notable record.

So the propeller kept humming and they continued to climb. A glance at the barograph by his side showed that he had reached five thousand feet; to this he added another thousand, then another, and he felt a thrill when the indicator made known he was close to nine thousand.

Although, as you may know, several aviators have mounted almost two miles, none had done so at the time of which I am now speaking. Harvey was near the limit, and he had but to persevere a little longer to achieve a grand triumph. But the cold was becoming almost unbearable. In the hope of moderating the piercing chill, he lessened his speed, but was not sensible of much improvement.

His unremitting attention was not needed and he turned his head and looked at Bohunkus. The sight made him laugh. The negro had not only drawn his upturned collar about his ears, with his cap sunk low over them, and his mittened hands shoved into his pockets, but he had shrunk within himself to that degree that only his staring eyes and the tip of his nose were visible. He was hunched together, and gave one of the best imitations imaginable of a young man freezing to death.

“I know his race doesn’t like cold weather, but it won’t hurt him,” reflected Harvey with another look at his barograph. To his astonishment, he had made no perceptible gain during the last several minutes. He turned on full power and kept the forward rudder inclined upward. He waited awhile before examining the instrument again. So far as it could indicate he was not a foot higher than before.

He was mystified. What could it mean? With the propeller revolving more than a thousand times a minute, he ought to have risen a half mile higher.

“I never heard of anything like it; the explanation is beyond me.”

With a thrill of misgiving, he glanced at the different parts of the machine. There were the two slightly curving wings, measuring thirty-five feet from tip to tip; the horizontal rudder on the front outrigger responded easily to the levers, as he proved by test; the ailerons or wing tips, one above the other, worked simultaneously and with the same ease; the ash which formed the foundation of the engine, the whitewood of the ribs, and the sprucewood of most of the structure, all scraped and highly varnished, did not show the least flaw. The rigidity which is indispensable in the framework was maintained throughout. The rubberized linen covering of the wings was taut and as smooth as silk, and the eye could not detect the slightest wire or thing out of gear.

“Professor Sperbeck never told me anything of this, though if he were here, he would understand it. I wonder whether we have climbed any farther.”

Another inspection of the instrument failed to show that the biplane had ascended an inch.

“Can it be that our height has anything to do with it——”

Harvey Hamilton uttered an exclamation. The mystery was solved. The aeroplane had risen so high that the rarefied air refused to lift it farther. The propeller was whirling at its utmost velocity, but the cold, thin atmosphere could sustain no more. It was impossible, situated as he was, to go any higher.

“If Bohunkus wasn’t with me, I could rise a half mile or more, but there’s no use of trying it now. Some time I’ll do it alone.”

The limit marked was a trifle under nine thousand feet. It was a notable exploit, but, as we know, it has been surpassed by other aeroplanes, and more than doubled by aeronauts.

Another fact flashed upon Harvey: it was two hours since he and his companion had started on the flight that was destined to be a memorable one, and they were a hundred miles from home. There could be only a small amount of gasoline left in the tank, and it would be impossible to return without procuring more. Prudence urged that he should lose no time in doing so. He slowly advanced the control lever, the front rudder dipped downward and he began approaching the earth. Some minutes must pass before they should feel the pleasant change of temperature, but it could not be long delayed.

In the midst of his pleasant anticipations, Harvey was startled by a shriek from Bohunkus:

“We’s gone, Harv!” he shouted; “nuffin can sabe us!”

CHAPTER V.

A WOODLAND EXPERT.

The aeroplane was caught in a furious snow squall. While descending it ran into the swirling tumult which in an instant enveloped it like a blanket, the myriads of particles filling the air so thickly that the terrified Bohunkus could not see the ailerons and even the aviator was partly shrouded from sight. Harvey Hamilton was faintly visible as he leaned over and manipulated the levers. Not only was the snow everywhere, but the machine itself was rocking like a ship laboring in a storm. It tipped so fearfully that the negro believed it was about to capsize and tumble them out. He shrieked in his terror, and held fast for life.

Harvey paid no heed to him. He had enough to engage his skill and wits. He recalled that Professor Sperbeck had told him what to do when caught in one of those elemental outbursts. Instead of running away from it, he headed for its center, so far as he could locate it, as the navigator does when gripped by the typhoon of the Indian Ocean.

Within five minutes of the aerial explosion, as it may be called, the biplane was sailing in the same calm as before. The sun was shining low in the sky and all was as serene as the mildest summer day that ever soothed earth and heavens. The gust had come and gone so quickly that it seemed like some frightful nightmare. The youths might have doubted the evidence of their senses, but for the reminder of the snowflakes on the wings, different parts of the machine and their clothing. They had entered so balmy a temperature, however, that the particles soon dissolved and left only a slight moisture behind them.

“Wal, if dat don’t beat all creation,” mused Bohunkus; “de fust ting I knowed I didn’t know anyting and de next dat I knowed wasn’t anyting. Wonder if Harv seed dat yell I let out when dat rumpus hit me on de side ob my head.”

The aviator acted as if unaware of the dusky youth’s presence. Knowing the gasoline was nearly gone, he centered his thoughts upon making a landing. To his astonishment he saw an immense forest below him, many miles in extent. This seemed remarkable in view of the fact that only a short time before he had sailed over a large city, which could not be far to the south. He would have turned about and made for it, knowing he could renew his supply of fuel there, and find accommodations for himself and companion. But the fluid was lower than he had supposed. It would not carry him thither and he must volplane, or glide to earth, the best he could.

It need not be said that a stretch of woods is the worst place in the world for an aeroplane to descend to the earth. In fact it is impossible to land without wrecking the apparatus and endangering the lives of those it is carrying.

The keen eyes of the youth were scanning the ground below when to his surprise he caught sight of a village of considerable size to the westward. Why he had not observed it before passed his comprehension. It was barely two miles distant and he was wondering whether he had enough gasoline left to carry him over the woods to the broken country beyond when he made a second and pleasing discovery. A short distance ahead an open space in the forest showed,—one of those natural breaks that are occasionally seen in wide stretches of wilderness. It was several acres in extent and seemed at that altitude to be free of stumps and covered with a sparse growth of dry grass, so level that it formed an ideal landing place. He did not hesitate to make use of it.

Now when an aeroplane comes down to earth, the greatest care is necessary to avoid descending too suddenly. A violent bump is likely to injure the small wheels beneath or the machine itself. The aviator therefore oscillates downward somewhat after the manner of a pendulum. When near the ground, he shifts his steering gear so that the machine glides sideways for a little way. Then he circles about or takes a zig-zag course, until it is safe to shut off power and alight. As our old friend Darius Green said, the danger is not so much in rising and sailing through the sky as it is in ’lighting.

Harvey Hamilton displayed fine skill, seesawing back and forth until at the right moment the three small wheels touched the ground, the machine under the slight momentum ran forward for two or three rods, and then came to a standstill. A perfect landing had been effected.

“Gee, but dat’s what I call splendacious!” exclaimed Bohunkus; “it’s jest de way I’d done it myself.”

The aviator leaped lightly from his seat, and his companion did so more deliberately. He yawned and stretched his arms over his head. Harvey gave him no attention until he had examined the different parts of the machine and found them in order. Then he looked gravely at the African and asked:

“Didn’t I hear you make some remark at the moment we dived into that snow squall?”

“P’raps yo’ did, for de weather was so funny dat it war nat’ral dat I should indulge in some obserwation inasmuch as to de same.”

“But why use so loud tones?”

“Dat was necessumsary on ’count ob de prewailing disturbance ob de atmospheric air wat was surrounding us.”

“I’m glad to hear your explanation, but it sounded to me as if you were scared.”

“Me scared! Yo’ hurts my feelings, Harv; but I say, ain’t yo’ gwine to tie de machine fast?”

“What for?”

“To keep it from running away.”

“It won’t do that unless some one runs away with it; but, Bunk, we can’t do any more flying till we get some gasoline and oil, and it doesn’t look to me as if there is much chance of buying any in these parts.”

“Mebbe we can git it ober dere.”

“Where?”

“At dat house jest behind yo’.”

Harvey turned about and met another surprise, for on the farther edge of the natural clearing stood a dilapidated log dwelling, with portions of several outbuildings visible around and beyond it.

“I must be going blind!” was his exclamation; “I came near passing this spot without seeing it and never noticed that house.”

But the young man was hardly just to himself. In his concentration of attention upon a landing place, he had given heed to nothing else, and the descent engaged his utmost care until it was finished. It was different with his companion, who had more freedom of vision. Moreover, the primitive structure which the aviator now saw for the first time was so enclosed by trees that it was hardly noticeable from above.

No fence was visible, but a small, tumble-down porch was in front of the broad door, which was open and showed a short, dumpy woman, slovenly dressed and filling all of the space except that which was above her head, because of her short stature. Her husband, scrawny, stoop-shouldered, without coat, waistcoat or necktie, wearing a straw hat whose rim pointed straight upward at the back and almost straight downward in front, with a yellow tuft of whiskers on his receding chin, and a set of big projecting teeth, was slouching toward the two young men, as if impelled by a curiosity natural in the circumstances. The thumb of each hand was thrust behind a suspender button in front, and it was evident that he felt some distrust until Harvey Hamilton’s genial “Good afternoon!” greeted him. His trousers were tucked in the tops of his thick boots, which now moved a little faster, but came to a stop several paces off, as if the owner was still timid.

“How’r you?” he asked with a nod, in response to Harvey’s salutation; “what sort of thing might you be calling that? Is it an aeroplane?”

“That’s its name; you have heard of them.”

“I’ve read about them in the newspapers and studied pictures of the blamed things, but yours is the first one I ever laid eyes on.”

Despite the uncouth manner of the man, it was evident that he possessed considerable intelligence. He stepped closer and made inquiries about the machine, its different parts and their functions, and finally remarked:

“It’s coming, sure.”

“What do you refer to?” asked Harvey.

“The day when those things will be as common as automobiles and bicycles. If I don’t peg out in the next ten years, I expect to own one myself.”

“I certainly hope so, for you will get great pleasure from it.”

“Not to mention a broken neck or arm or leg,” he remarked with a chuckle. “Now I suppose you call this contrivance a biplane because it has double wings?”

“That is the reason.”

“And it seems to me,” he added, turning his head to one side and squinting, “the length is a little greater from the nose of the forward rudder to the end of the tail than between the wing tips?”

“You are correct again; there is a difference of about two feet.”

“The wings are curved a bit; I have read that that shape is better than the flat form to support you in air.”

“Experiments have proved it so.”

“And this stuff,” he continued, touching his forefinger to the taut covering of one of the wings, “is rubberized linen?”

“It is with our machine, though some aviators prefer other material.”

“Spruce seems to be the chief wood in your biplane.”

“Because of its lightness and strength.”

“The horizontal rudder in front must be used in ascending and descending and the two vertical ones at the rear for steering your course. I should judge,” he said, scrutinizing the motor, “that your engine has about sixty-horse power.”

“You hit it exactly; I am astonished by your knowledge.”

“It all comes from remembering what I read. And the wing tips are the ailerons, and the engine weighs about three hundred pounds.”

“A trifle less, the whole weight of the aeroplane being eight hundred pounds.”

“Your propeller is made of black walnut, and has eight laminations, and when under full headway revolves more than a thousand times a minute.”

“See here,” said Harvey; “don’t say you haven’t examined aeroplanes before.”

“As I told you, I never saw one until now, but what’s the use of reading anything unless you keep it in your memory? That’s my principle.”

CHAPTER VI.

WORKING FOR DINNER.

Further conversation justified the astonishment of Harvey Hamilton. The countryman, who gave his name as Abisha Wharton, showed a knowledge of aviation and heavier-than-air machines such as few amateurs possess. In the midst of his bright remarks he abruptly checked himself.

“What time is it?”

Harvey glanced at the little watch on his wrist.

“Twenty minutes of six.”

“You two will take supper with me.”

Bohunkus Johnson, who had been silently listening while the three were standing, heaved an enormous sigh.

“Dat’s what I’se been waitin’ to hear mentioned eber since we landed; yas, we’ll take supper wid yo’; I neber was so hungry in my life.”

“I appreciate your kindness, which I accept on condition that we pay you or your wife for it. We have started on an outing, and that is our rule.”

“I didn’t have that in mind when I spoke, but if you insist on giving the old lady a little tip, we sha’n’t quarrel; leastways I know she won’t.”

“That is settled then. Now I should like to hire you to do me a favor. I don’t suppose you keep gasoline in your home?”

“Never had a drop; we use only candles and such light as the fire on the hearth gives.”

“How near is there a store where we can buy the stuff?”

“I suppose Peters has it, for he sells everything from a toothpick to a folding bed. He keeps the main store at Darbytown, two miles away. I drive there nearly every day.”

“Will you do so now, and buy me ten gallons of gasoline and two gallons of cylinder oil?”

“I don’t see why I shouldn’t; certainly I’ll do it. Do you want it right off?”

“Can you go to town and back before dark?”

“My horse isn’t noted for his swiftness,” replied Abisha with a grin, “but I can come purty nigh making it, if I start now.”

“Dat’s a good idee; while yo’s gone, Harv and me can put ourselves outside ob dat supper dat yo’ remarked about.”

Harvey’s first thought was to accompany his new friend to the village, but when he saw the rickety animal and the dilapidated wagon to which he was soon harnessed, he forebore out of consideration for the brute. Besides, it looked as if he was likely to fail with the task. Accordingly, our young friend handed a five-dollar bill to his host and repeated his instructions. Then he and Bohunkus sauntered to the rude porch, where Mrs. Wharton came forth at the call of her husband, and was introduced to the visitors, whose names were given by Harvey. She promised that the evening meal should suit them and passed inside to look after its preparation.

The winding wagon road was well marked, and Abisha Wharton, seated in the front of his rattling vehicle, struck his bony horse so smart a blow that the animal broke into a loping trot, and speedily passed from sight among the trees in the direction of Darbytown. Harvey and Bohunkus, having nothing to hold their attention, strolled to the woodpile and sat down on one of the small logs lying there, awaiting cutting into proper length and size for the old-fashioned stove in the kitchen. A few minutes later the wife came out and gathered all that was ready for use. As she straightened up, she remarked with a sniff:

“That Abisha Wharton is too lazy ever to cut ’nough wood to last a day; all he keers about is to smoke his pipe, or fish, or read his papers and books.”

When she had gone in, Harvey said to his companion:

“We haven’t anything to do for an hour or so; let’s make ourselves useful.”

“I’m agreeable,” replied Bohunkus, lifting one of the heavy pieces and depositing it in the two X’s which formed the wood horse. The saw lay near and was fairly sharp. The colored youth was powerful and had good wind. He bent to work with a vigor that soon severed the piece in the middle. He immediately picked up another to subject it to the same process, while Harvey swung the rather dull axe and split the wood for the stove. It was all clean white hickory, with so straight a grain that a slight blow caused it to break apart. The work was light and Harvey offered to relieve his companion at the saw.

“Don’t bodder me; dis am fun; besides,” added Bohunkus, “I cac’late to make it up when I git at de supper table; I tell yo’, Harv, yo’ll hab to gib dat lady a big tip.”

“I certainly shall if I wish to save her from losing on you.”

For nearly an hour the two wrought without stopping to rest. By that time, most of the wood was cut and heaped into a sightly pile. The odor of the hickory was fragrant, and it made a pretty sight, besides which we all know that it has hardly a superior for fuel, unless it be applewood.

By and by the woman of the house came to the door and looked at the two boys. She was delighted, for she saw enough wood ready cut for the stove to last her for a week at least. Bohunkus was bending over the saw horse with one knee on the stick, while a tiny stream of grains shot out above and below, keeping time with the motion of the implement, and Harvey swung the axe aloft with an effect that kept the respective tasks equal. Gazing at them for a moment, the housewife called:

“Supper’s waiting!”

“So am I!” replied Bohunkus, who, having a stick partly sawn in two worked with such energy that the projecting end quickly fell to the ground. Harvey would not allow him to leave until the pieces were split and piled upon the others.

“Now let us each carry in an armful.”

They loaded themselves, and Harvey led the way into the house, where the smiling woman directed them to the kitchen. There being no box they dumped the wood upon the floor, then seated themselves at the table, and she waited upon them.

Despite her untidy appearance, Mrs. Wharton gave them an abundant and well-cooked meal, to which it need not be said both did justice. They were blessed with good appetites, Bohunkus especially being noted at home for his capacity in that line. They pleased the hostess by their compliments, but more so by their enjoyment of the meal.

It was a mild, balmy night, and at the suggestion of the woman they carried their stools outside and sat in front of the house and on the edge of the clearing, to await the return of the master of the household. Sooner than they expected, they heard the rattle of the wheels and the sound of his voice, as he urged his tired animal onward. It took but a few minutes for him to unfasten, water and lead him to the stable. Then the man came forward and greeted his friends.

“How did you make out?” asked Harvey.

“I got what I went after, of course; the gasoline and oil are in the wagon, and there’s about three dollars coming to you.”

“Which you will keep,” replied Harvey. “We have finished an excellent meal and shall wait here for you if you don’t mind.”

“I’m agreeable to anything,” remarked the man, as he slouched inside, where by the light of a candle he ate the evening meal with his wife. Our friends could not help hearing what she said, for she had a sharp voice and spoke in a high key. She berated him for his shiftlessness and declared he ought to be ashamed to allow two strangers to saw and split the wood which had too long awaited his attention. She made other observations that it is not worth while to repeat, but evidently the man was used to nagging, for it did not affect his appetite and he only grunted now and then by way of reply or to signify that he heard.

When Abisha brought out his chair and lighted his corncob pipe, it was fully dark. The night was without a moon, and the sky had so clouded that only here and there a twinkling star showed.

“Do you ever fly at night?” asked their host.

“We have never done so,” replied Harvey, “because there is nothing to be gained and it is dangerous.”

“Why dangerous?”

“We can’t carry enough gasoline to keep us in the air more than two hours, and it is a risky thing to land in the darkness. If I hadn’t caught sight of this open space, it would have gone hard with us even when the sun was shining.”

“It’s a wonderful discovery,” repeated Wharton, as if speaking with himself, “but a lot of improvements will have to be made. One of them is to carry more gasoline or find some stuff that will serve better. How long has anyone been able to sail with an aeroplane without landing?”

“I believe the record is something like five hours.”

“In two or three years or less time, they will keep aloft for a day or more. They’ll have to do it in order to cross the Atlantic.”

“There is little prospect of ever doing that.”

“Wellman tried it in a balloon, but was not able to make more than a start.”

“I agree with you that the day is not distant when the Atlantic will be crossed as regularly by heavier-than-air machines as it is by the Mauretania and Lusitania, but in the meantime we have got to make many improvements; that of carrying enough fuel being the most important.”

At this point Bohunkus felt that an observation was due from him.

“Humph! it’s easy ’nough to fix dat.”

“How?”

“Hab reg’lar gasumline stations all de way ’cross de ocean, so dat anyone can stop and load up when he wants to.”

“How would you keep the stations in place?” gravely inquired Wharton.

“Anchor ’em, ob course.”

“But the ocean is several miles in depth in many portions.”

“What ob dat? Can’t you make chains or ropes dat long? Seems to me some folks is mighty dumb.”

“I’ve noticed that myself,” remarked the host without a smile. Failing to catch the drift of his comment, Bohunkus held his peace for the next few minutes, but in the middle of a remark by his companion, he suddenly leaped to his feet with the gasping question:

“What’s dat?”

CHAPTER VII.

THE DRAGON OF THE SKIES.

The others had seen the same object which so startled Bohunkus. Several hundred feet up in the air and slightly to the north, the gleam of a red light showed. It was moving slowly in the direction of the three, all of whom were standing and studying it with wondering curiosity. It was as if some aerial wanderer was flourishing a danger lantern through the realms of space.

“What can it be?” asked Abisha Wharton in an awed voice.