Little "Why-Because"

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

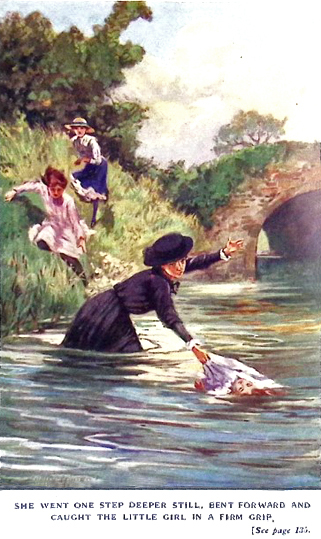

SHE WENT ONE STEP DEEPER STILL, BENT FORWARD AND

CAUGHT THE LITTLE GIRL IN A FIRM GRIP.

Little "Why-Because"

By

AGNES GIBERNE

Author of "Sun, Moon and Stars," "Five Little Birdies,"

"Stories of the Abbey Precincts," "Through the Lynn," etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY DUDLEY TENNANT

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 Bouverie Street and 65 St. Paul's Churchyard E. C.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

I. FIDGETS

II. QUITE IMPOSSIBLE

III. THE "VICARAGE DOG"

IV. LITTLE IVY

V. THE WONDERFUL NEWS

VI. BUTTONS AND BUTTON-HOLES

VII. ANOTHER SIDE OF IVY

VIII. HECLA IN CHARGE

IX. SUCH A TEMPTATION

X. GREAT DANGER

XI. CONSEQUENCES

XII. THAT DELIGHTFUL TOY-SHOP

XIII. ONLY THINK

LITTLE "WHY-BECAUSE"

CHAPTER I

Fidgets

"AUNTIE, what does 'ruthless' mean?"

"Why do you wish to know, Hecla?"

"I saw it in a book."

"You shall show me the passage by-and-by. Just now you have to work."

Hecla was hemming a small pocket-handkerchief, with red edges. She liked doing this, because it was for "Chris," but she did not love work for its own sake. She liked nothing which meant sitting still.

Hers was a rather curious name. She had been born in Iceland, under the shadow, so to speak, of Mount Hecla. That was why she was so called.

She sat at a small table in the middle of the room, with her back to the window, and Miss Storey, a slender, small, middle-aged lady, was near the fire. At Miss Storey's feet lay a fine black Persian cat, fast asleep; and in the window hung a gilt cage, the canary within ever hopping from perch to perch, except when it stopped to feed or to sing.

Sunshine streamed full upon the cage and upon the draped white curtains. It was a sunny day, but very cold, and patches of snow in the front garden told of a recent fall.

Miss Storey kept very upright and very still, and her small delicate fingers scarcely seemed to move as they knitted. But Hecla was neither upright nor still. She was a restless little mortal; quite as restless as the canary in its cage. She too was slim, and also rather tall for her age; and she had an anxious way of wrinkling her forehead, as if trying to do something beyond her power. She wore a brown holland pinafore over a brown stuff frock, and her hair hung in limp rats' tails down her back.

"Auntie, why does Chris learn Latin, and me not?"

"You may perhaps learn Latin some day, my dear. It is not necessary for you at present."

Hecla managed five stitches in silence.

"Auntie, isn't it most dreadfully cruel of the blackbirds to eat worms? Why don't they eat crumbs—that would be ever so much nicer? I do think it's cruel, don't you?"

"No more cruel than it is of Hecla to eat mutton."

Another pause. Hecla pushed her needle in and out.

"Auntie—"

"Go on with your work, dear."

"I'm going. Auntie—"

"My dear child, you will finish much sooner if you do not talk. Try now!"

Hecla did try. She screwed her forehead into all sorts of shapes, huddled herself into a bunch, and asked no questions for nearly two whole minutes. Her chair kept up a gentle creaking.

"You need not fidget, Hecla."

There were no sounds for quite thirty seconds. Then she forgot. Out went one foot and the other curled itself round the leg of her chair. Her elbow sprawled over the table, and down went a reel of cotton. It rolled away, so of course she had to run after it; and when she came back and plumped into her chair—crash followed.

"My dear Hecla!"

"Oh, auntie, it's my work-box! I'm so sorry!"

"Pick it up carefully. Then you must try to be quiet."

Picking up the fallen box and putting its contents straight was easy. But to be quiet—there lay the difficulty. Do what Hecla would, and try as she might, it always seemed as if the one impossible thing for her was to keep still.

"I've done one whole side of my handkerchief, auntie." She jumped up—and bang! again. Down went her chair, backwards.

"Hecla!"

"Oh dear! Things will tumble so, auntie."

"Not unless they are made."

"I didn't try—truly, I didn't!" Hecla's forehead was all over crinkles.

"No, dear. But did you try not?"

Hecla was not sure. She brought the handkerchief to her aunt, and stood waiting while Miss Storey put on her glasses. But you must not suppose for a moment that Hecla stood still and upright, like a soldier. Nothing of the sort! First she balanced herself on one leg, and then she balanced herself on the other; now she clasped her hands behind her back, and then she stretched them high over her head; next, she gave a skip, and pranced round to the back of Miss Storey's chair.

"Stand still."

Hecla said "Yes," and danced back.

"It is not badly done. One more side, and Elisabeth shall take you out."

That brought another prance. "Oh, I do like going out, and I love going with Elisabeth."

"But you must do as Elisabeth tells you."

"Oh yes, of course, auntie."

She sat down, began again, did six stitches, and sighed. "They are such long sides!"

"I wonder what you would feel if you had all round a great sheet to hem. I did that when I wasn't much older than you are now."

Hecla was deeply interested. She put down her work, and gazed earnestly at Miss Storey.

"Weren't you much older than me, auntie?"

"I was just ten years old."

"Ah, but I'm only eight and a half. I'm 'xactly eight and a half."

"Eighteen months is not so very much difference."

Privately Hecla thought the difference enormous. She felt that at ten years old she would be very nearly grown-up. But she only asked, "What made you hem the sheet? Was it—for punishment?"

"No, not at all. The sheet had to be hemmed, and I wanted to help my mother."

Hecla considered the question with knitted brows. She felt convinced that her aunt must have been an extraordinarily good little girl, far superior to all little girls whom she had known, especially superior to herself. Hecla was most anxious to be good, and her great desire was to please everybody; but the idea of hemming even one side of anything so vast as a sheet—that simply lay outside the world of things possible!

"Weren't you obliged to do it?" she inquired hopelessly.

"No, certainly not. I used to get up in the early morning, and get a piece done before breakfast."

More and more astonishing. "Not in winter, auntie."

"Yes, in winter."

Hecla gave it up as a hopeless case. She was generally wide-awake enough at night, but profoundly drowsy in the morning—at least, in winter mornings.

"I shouldn't like to have to hem a sheet. It would take me—oh, I think a whole, whole year."

"Not unlikely, at your present rate."

Hecla understood, and felt ashamed. She picked up the handkerchief which lay at her feet and set to work anew. Silence actually lasted for nearly five minutes, by which time she felt that she was almost rivalling Miss Storey's past goodness.

It was a fair-sized room in which they sat, crowded with heavy old-fashioned furniture. Each chair, not in use, stood rigidly with its back against the wall, only never touching it, for fear the pretty paper might be rubbed or scratched. The semi-grand piano—on which nobody ever played, for Hecla practised on another—was laden with handsome old china and framed photographs, always arranged in the same manner. On the mantelpiece were a number of valuable vases, placed in a row. An ornamental corner bookcase held many handsome calf-bound volumes, each of which had invariably the same neighbours.

Miss Storey and her sister disliked changes. They had lived here all their lives, seldom going away even for a short time; and they did their best to keep everything both inside and outside the house exactly what it had always been. That, at least, was Miss Storey's aim; and whether Miss Anne felt the same or not, she seldom differed from her sister.

Until the coming of little Hecla, some eighteen months before this date, nothing had disturbed the even tenor of their lives since Miss Storey's girlhood. Everything in the house had gone steadily on, as if by clockwork—like the aged timepiece in the hall, which never was known to lag behind or to run ahead.

Nothing and nobody under that roof had ever been in a hurry, or afflicted with fidgets. Certainly not Miss Storey, or Miss Anne Storey, or the elderly servant who had done most of the work, or the stolid young girl who helped her, or the silent old charwoman who sometimes came for a day's work, or even the dignified Persian cat. All had gone on calmly, smoothly, placidly.

But when their only sister died, leaving one little girl alone and friendless, it became their duty to take her. And they did not hesitate. They determined at once to have the child, though they—especially Miss Storey—felt that it would be a trial.

And it no doubt was a trial. Though they were very fond of the child, she worried them a good deal, without in the least meaning to do so.

Miss Storey was not really old. Many a woman of her age is still active and vigorous, and even young, and Miss Anne was many years the younger of the two. Still, they had lived so long in one particular way, that it was not easy for them to change.

And with the coming of little Hecla, an eager, affectionate, talkative, restless child of seven, accustomed to be made much of and to get her own way more than was perhaps wise, things were a good deal altered. It could not be otherwise.

For years and years the sisters had lived in quiet, and had had everything about them neat and regular and orderly. All at once, into the midst of this placid household came a little fidgety sprite, never for a moment still, never, if she could help it, for a moment silent, always on the go, always wanting to do something fresh, perpetually asking questions, never putting anything away into its right place, unable to write without scattering ink-spots, unable to kiss them without rumpling their nice white frills. It really was something of a trial at first even to Miss Anne, and it was a very great trial to Miss Storey. Not even eighteen months of it had made the elder sister grow used to the new state of things.

Do what they might, they could not shape the child into their own ways. She really was on the whole a good little girl, anxious to do what was right. But she forgot words of reproof almost as soon as they were spoken; and it seemed as if she positively had to dance and skip and prance and fidget and chatter the whole day long without a break.

Perhaps the aunts had done much the same in their childhood, and had forgotten; or, if Miss Anne remembered, she never said so. Perhaps they had been naturally less restless. There is a great difference between different children, just as there is a great difference between different grown-up people.

Hecla never for a moment dreamt what a trial her presence in the house was to her Aunt Millicent. She knew that she was always being told not to fidget, but she supposed that to be only because she had to learn to be proper and quiet.

Sometimes she wondered why the aunts liked to sit so still, and to move so slowly; and why she might not jump up and down and race round and round just as often as she felt inclined. But she never questioned in her little heart their real kindness and love; and it never so much as came into her head that she could be a trouble to either of them.

CHAPTER II

Quite Impossible

"THAT is done. Now you may go," said Miss Storey, quite as glad as Hecla was, for she had a great anxiety on her mind, and she was longing to be alone that she might consider what to say to her sister, Anne, who might come in at any moment.

Hecla rushed off like a small whirlwind, only to be called back.

"You are forgetting everything, my dear. Put your work away—neatly!—your thimble and cotton in the box—and pick up those bits of cotton. And set your chair in the right place. No, not there!" As Hecla ran it against another chair, with a bang.

Miss Storey sighed. "When I was your age, I did not need to be told the same things over and over every day."

"Not when you were ten years old!"

"No; nor when I was eight."

Hecla stood motionless; the chair tilted up on its back legs as she held it.

"Weren't you never naughty, auntie?"

"No doubt I was sometimes. All children are. But I do not think I often forgot things that I was told to do."

Hecla left the chair tilted on one side, with a foot on a stool, and came close to Miss Storey.

"Won't you tell me, please, about when you really truly were a naughty child, auntie? Please do."

Miss Storey gazed with rather puzzled eyes into the anxious little face.

"I think you ought rather to wish to hear about when I was good," she said patiently, though that crooked chair tried her dreadfully, and she did so long to be by herself.

"But you've told me that—oh, heaps of times! And I do want to know about when you did something naughty—ever so naughty!"

"Not now. Perhaps some other day, when you have been particularly good. I don't say you have been exactly naughty to-day, but still I should like to see you trying a little harder not to forget everything you are told. Now you have to go out."

And actually—again!—Hecla was marching off, without a thought of that unfortunate chair. Again she had to be called back, and again she rammed it hastily into the wrong place, banging the back of another chair against the wall-paper, which the two aunts were always so careful to guard from unsightly marks. Of course the bang left a dent, and when at length Hecla vanished, Miss Storey sighed and closed her eyes, and murmured—

"What a child it is! And to think of—another! Impossible!"

Back whisked Hecla, bursting open the door, and rushing across the room.

"Oh, auntie, please! May I go and see Chris?"

"Not to-day."

"Please! I want to see him—ever so much!"

"No, not to-day."

"Only just for one minute, auntie!"

"No. That is enough, Hecla. Do as you are told. You are to have a walk in the country—not to the shops. Remember."

Hecla went away slowly, and Miss Storey folded her hands together, setting herself to think. With that restless little being in the room, she had found thinking out of the question.

No sooner had she settled herself than the door opened again, this time very gently. A lady appeared, just a little taller than herself and quite as slim, but younger-looking. Miss Storey's hair was fast turning grey, while Miss Anne's was all a soft light brown. She wore a shady hat, and she had pretty, kind, blue eyes.

"Anne! Sit down, my dear. I want to tell you something."

Miss Anne obeyed slowly. She had been educated never to do anything in a hurry.

"The second post has brought me a letter from Frederick. He asks something unexpected—something which I really do not think we can grant. I do not see that it is possible." Miss Storey spoke in a troubled voice. "I really do not think we can!"

Miss Anne made a little movement, as if holding out her hand for the letter, but she checked herself.

"Yes, you shall see it. I wish you to see it. In fact, it is written to you as well as to me. But I wanted to prepare you first. It came upon me quite as a shock. All the morning I have had it on my mind, and Hecla has been more forgetful than ever—really very trying, poor child. But you will see what they ask—Frederick and Mary, I mean. He has the offer of a good appointment in a place very unhealthy for children. They cannot take little Ivy, and Mary says she cannot let her husband go without her. And they ask—us!"

Miss Anne read the letter slowly. Then she looked up at her sister and read it again.

"You see! The thing is impossible. Quite impossible! A child of five! To come here as if our hands were not full enough already! A child of five! What a dreadful idea!"

Miss Anne's soft blue eyes had a curious light in them. She did not look as if the idea were so dreadful to her.

"I cannot imagine what they are thinking about to ask such a thing," pursued Miss Storey, her little thin hands trembling. "Of course, when our dear sister was taken from us, there could be no question about giving a home to her child. But this is not at all the same. Frederick is only our cousin."

"Our only first cousin!" murmured Miss Anne.

"Yes, but still—he really has no right to expect anything of the sort. And—five years old! Such a troublesome, mischievous age. Hecla is trying enough, so careless and forgetful. Still, she does understand, when one explains to her. But—five years old—a mere baby! We should have to send Elisabeth away, and have an older servant. Impossible!"

"But—" uttered Miss Anne.

"You have read it all!"

"Twice through. You see, Frederick would not let it be any expense to us."

Miss Storey held up her head. "If the child came, I certainly would not be paid for it. Quite out of the question!"

"Frederick seems to think he ought not to refuse this offer."

"I suppose he ought not. But—Mary might remain behind for a time."

"And let him go alone? Oh no! And, Millicent, they have nowhere else to send the little one, except to school. Think! School at five years old! Poor wee pet!"

"Other people have the same difficulties, my dear Anne. I do not see that we are called upon to give a home to all the children in the Storey family. It is out of the question. Quite out of the question."

The sparkle in Miss Anne's blue eyes was quenched.

"Then I suppose you will write and tell Frederick that he must send Ivy to school."

"I shall write and explain. There is nothing else to be done."

Miss Storey gazed round the room, seeing in imagination a small rampageous infant rushing about, teasing the canary, worrying the cat, upsetting everything, behaving altogether precisely as little girls of five should not behave. "It is impossible," she said again. "Frederick ought not to have asked such a thing of us."

"If it cannot be, I suppose there is no more to be said," Miss Anne regretfully observed, standing up. "I am sorry. Poor little Ivy!"

"We are just beginning to get Hecla a little into order; and another child in the house would upset her completely. They would make one another naughty. No, dear Anne, it cannot be. I am quite decided."

"Then you will write," Miss Anne said, and she went out, that her sister might not see tears in her eyes.

In the passage, Hecla ran plump against her.

"Gently, dear. Where are you going?"

"Out for a walk." Hecla's face was all sunshine again, and she held it up for a kiss.

"Elisabeth and I are going."

"Where is Elisabeth?"

"She'd got to do something first in the kitchen, and she said she'd meet me at the back gate."

"I'll walk down the garden with you."

Sometimes, when Miss Storey was not at hand, Miss Anne would indulge in a little run with her niece; and she did so now. Hecla slipped an arm through hers, pulling hard, and Miss Anne ran briskly all down the back garden pathway.

"Auntie, I wish you'd come for a walk."

"I'm wanted indoors, dear. I have been out already."

"Elisabeth can't tell me stories; and I like stories. Auntie Anne, weren't you ever naughty when you were a little girl?"

"Very often naughty, I'm afraid."

That was consoling. "I'm glad. Won't you tell me some day all about your being naughty?"

"Perhaps, some day. But you mustn't be glad, Hecla. You ought to be sorry when people are naughty."

"If it was a grown-up person that was naughty!" suggested Hecla. "But not if it was once you, auntie."

Miss Anne was puzzled, not seeing what the child meant.

"Here is Elisabeth," she said. "Now be sure you get back in good time. Elisabeth has to lay the cloth, you know, at one o'clock. You have just an hour."

Hecla nodded, smiled, promised, and ran off, Elisabeth trying to catch her.

Miss Anne walked slowly back to the house, pausing on the way to look at her favourite flowers, and thinking hard about poor Frederick and Mary, obliged to leave their dear little child behind, and not knowing where to send her.

"If only we could take little Ivy in! I should love to have another," she whispered. "Children in the house make life so different!" Then she looked up, almost guiltily, as if it were wrong not to feel as her sister did. And yet again she murmured aloud: "Poor little Ivy! If only we might!"

Later she returned to the drawing-room, where Miss Storey sat as before, calmly knitting. A letter lay at her side, addressed and stamped.

"I have written to Frederick, Anne."

Something in Miss Storey's face brought a gleam of hope. She looked tired and pale, but the smile was unusual. Miss Anne almost held her breath.

"I have told Frederick that we will give little Ivy a home. I could not say anything else when I began to—Why, my dear Anne!"

For Miss Anne broke into a little cry of joy, and dropped down on her knees in front of Miss Storey's chair, looking up with eyes that overflowed.

"My dear Anne! You are quite agitated."

"I'm so glad—so glad!" almost sobbed Anne. "I could not bear to think of that poor little pet going away among strangers when we might—when perhaps we could have had her. Thank you, dear Millicent."

"Why did you not tell me that you wished it so much?"

"I could not, of course, if you felt that it was impossible."

"I did feel so at first, very strongly. But when I began to write, somehow there was nothing else to be done." Miss Storey hesitated, and a faint pink flush rose in her cheeks. "It seemed to me, I—saw—I seemed to see our dear Lord, when the little children were brought to Him—taking them in His Arms. And I wondered if, perhaps, He wanted us to take little Ivy for Him, and then—then—I could do nothing else but write and tell Frederick. It will be something of a trial, no doubt, but still—still—if it has to be—"

Miss Storey sighed, yet smiled bravely, and Miss Anne looked radiant.

"Dear Millicent, I'm sure you never will regret it. Ivy was such a little darling when we saw her last."

"Two and a half years old! But she is five now."

"She shall not be any trouble to you—if I can help it."

"Ah! But all will be right. We cannot do anything else," said Miss Storey.

CHAPTER III

The "Vicarage Dog"

"I WANT to go round by the windmill, Elisabeth."

"I'm afraid there ain't time, Miss Hecla. We haven't got but just an hour."

"Oh, but there is. I know there is. We can run, you know. Do please say yes—there's a dear Elisabeth!"

Hecla looked beseechingly into her companion's round, rosy face and honest eyes. Elisabeth was only sixteen years old, which is not really old, though Hecla looked upon her as very much grown-up indeed. She often wished to be sixteen herself, because she felt that then she would be able to do whatever she liked. Elisabeth had been in Miss Storey's service ever since leaving school at twelve years of age, and she was a careful, dependable girl. She was devoted to Hecla, and loved nothing better than taking the little girl out for a ramble.

"It's a good bit round by the windmill," she hesitated, pulling out her neat metal watch, of which she was very proud, for it had been given to her by Miss Storey on the day when she completed four years in the house.

"We'll race," urged Hecla. "Do, please, come!"

"It's two minutes past twelve, and we haven't got but hardly an hour, Miss Hecla."

"You said that before. Make haste. We're wasting time now—ever so much!"

"And I mustn't be one minute late. Not one minute," pursued Elisabeth stolidly, though she began to move. "If I am, Mrs. Prue will begin laying of the table, soon as ever the clock strikes, and then—my! I shan't hear the end of it."

"Prue," otherwise Prudence Brown, was the servant who had been with the Miss Storeys for thirty years past. And it was thought more respectful for a young girl like Elisabeth to call her "Mrs. Prue."

"But we won't be late," declared Hecla. "Come along. Let's hurry."

"I don't mind starting that way, and then we'll see," Elisabeth said. "If you won't stop to look at every single thing, we could do it, Miss Hecla."

"Of course I won't," cried Hecla, setting off full speed.

And the next minute she came to a standstill, as a small fox-terrier, with muddy feet, rushed up and began leaping upon her. "Trip, you sweet dog, how nice! Trip means to come with us for a walk. He may, mayn't he?"

"Oh dear me, what a mess he is making of your frock, Miss Hecla!"

"Down, Trip, down!" shrieked Hecla, in fits of laughter, as Trip struggled to lick her nose. "You dear!" And she hugged him vehemently. "Come along—come! We'll run now, won't we?" And she started again, all unmindful of the muddy streaks down her skirt.

Elisabeth looked ruefully at those streaks, but she gave in, and hurried after the scampering child and dog. If they only kept going at this pace, there would be no difficulty in getting back by one o'clock.

Trip was the "Vicarage Dog," known to everybody in this small town of Nortonbury, and a great friend of Hecla. When Chris was at school, and when his master was busy in the study, Trip would sally forth alone in search of amusement. Sometimes he had to be content with racing after birds; sometimes he had the delight of a mad scramble after a cat; but if only he could come across Hecla, he was perfectly happy.

Under no consideration might Trip be ever admitted into "The Cottage,"—that being the name of Miss Storey's pretty little house. Miss Storey had a great objection to dogs; partly on account of her dear cat, partly for fear of dusty or muddy footmarks on doorsteps and carpets. Trip was afflicted with an ardent longing to go where Hecla was; and he had tried, times without number, to sneak into "The Cottage" by a side entrance. But Mrs. Prue felt like her mistress, and waged war on his kind. The moment Trip's black nose showed itself, he was sure to be sent flying by broomstick or poker, to comfort himself outside at a safe distance with a fury of barks.

Here in the lanes he might follow the little girl to his heart's content; and nobody would find fault, if only he would refrain from jumping on Hecla with those muddy paws. Elisabeth scolded him in vain; for so soon as she began to scold, Hecla felt sure his feelings must be hurt, and then she tried to comfort him, which made him jump on her more vigorously than ever.

"I shall have to give you a good brushing the moment we get back," Elisabeth said despondingly. "And that'll take time too, Miss Hecla."

"But we won't be late," Hecla replied gaily.

Time fled fast, and one-half of the hour had slid away, as such hours do slide, out in the sunshine and the fresh air, when she cried—

"Oh, look! There's a dear sweet little robin!" And she stopped to seize Trip by the collar. "Look—look—just on the path. Hasn't he nice bright eyes? No, Trip—you shan't frighten the dear little robin. Oh, you naughty doggie!"

For Trip broke loose, and tore after the robin, which of course flew away. Trip pursued, then vanished into a small plantation, from which he did not come out in a hurry.

Hecla called, Elisabeth called, in vain. They tried coaxing, and they tried scolding; but Trip was a dog who liked his own way quite as much as little girls and boys do; and nearly ten minutes passed before it pleased him to walk out, with an innocent face, as if much surprised that anybody should be in a hurry.

"You bad, bad Trip, to keep us all this time!" Hecla pretended to beat him, and then kissed the top of his head, which of course meant more leaping up, and fresh attempts to lick her cheeks.

"And he's been and got into more wet mud, and he's making of your frock worse than ever!" declared Elisabeth ruefully.

Wherever the sun shone, a thaw went on, and this meant many muddy patches.

"Dear me, whatever will Mrs. Prue say?" Elisabeth again pulled out her watch. "We've got to turn back this minute, Miss Hecla. There ain't no time for the windmill to-day. Trip's hindered us a deal too long."

"What a pity! I do want to go round," exclaimed Hecla. "Couldn't we run very, very fast?"

"No, we couldn't, Miss Hecla, and we ain't agoing to try. I've had enough o' that!" Elisabeth turned resolutely round as she spoke, and set off.

And Hecla, after one deep sigh of disappointment, started running in advance.

Trip lagged behind, with drooping tail, very much disgusted, for he knew that this meant going home, and he didn't want to go home.

But Hecla, whatever her faults might be, was not in the habit of showing sulks when she could not have her own way.

"I know what I'll do," she cried suddenly. "I know what I'll do! The quarry is only just round that corner, and I do want to see if I can't find some snowdrops for Auntie Anne. It won't take a minute!"

She shouted the words, turning her head back; and before Elisabeth could open her mouth to protest, she was flying at full speed round the next turn to the right, down a little narrow lane, which led to a small quarry, long ago disused, and now well grown over with grass and bushes. A particularly steep path led to the bottom; and by the time Elisabeth arrived at the edge, Hecla had rushed down this path at break-neck pace—fortunately without any slip, or she might have rolled the whole way—and was diving eagerly among grass and moss in the farther corner.

Elisabeth stood waiting above, for she was not sure-footed, and she did not care to try that path.

"Come, Miss Hecla—come!" she kept calling.

And presently Hecla rushed back, scrambling up the steep path in great haste.

"I've got them! I've got them!" she cried, radiant with delight. "Look! Three lovely little snowdrops! Won't Auntie Anne be glad!"

"I can't stop one moment, Miss Hecla. We're late. It was downright naughty of you to run off there without leave. And you knowed I'd got to get back."

Good-natured Elisabeth was for once really vexed. She took firm hold of Hecla's hand, and they ran together till they were breathless, slackening then for a minute, only to run again.

But their efforts were in vain. As they entered the front door, panting and red-checked, and Hecla all over muddy marks, Mrs. Prue, with a particularly grim face, was seen carrying an empty tray from the dining-room. And Miss Anne came out and said—

"Elisabeth, you are not in time. You should have brought Miss Hecla home earlier. I thought I could depend upon you. It is ten minutes past one."

"I'm sorry, ma'am," Elisabeth answered, and not one word did she utter in self-defence.

But, though Hecla could be forgetful and careless, she could not stand by and see Elisabeth blamed for what was her fault.

"It was me, auntie," she said. "It wasn't Elisabeth. I wanted to get these snowdrops, and I ran into the quarry. They're for you, auntie—because I love you."