Marigold's Decision

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

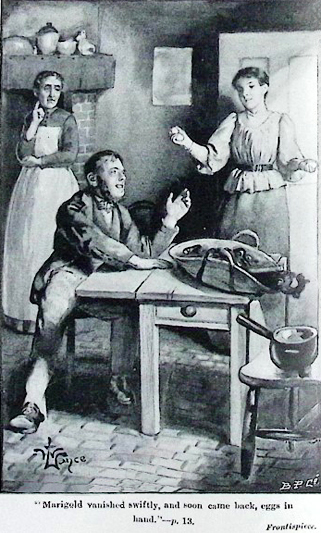

Marigold vanished swiftly, and soon came back,

eggs in hand. Frontispiece.

MARIGOLD'S DECISION

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF "MISS CON," "ST. AUSTIN'S LODGE," "DECIMA'S PROMISE,"

"THE ANDERSONS," ETC. ETC.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY W. LANCE

London

JAMES NISBET & CO.

21 BERNERS STREET

1896

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

I. WHAT SORT OF PEOPLE THEY WERE

II. SERVICE

III. WILD BEASTS

IV. A VISITOR

V. LATE AT NIGHT

VI. MARIGOLD'S LIKING

VII. MRS. PLUNKETT'S TROUBLE

VIII. A DECISIVE STEP

IX. NOT SO BAD

MARIGOLD'S DECISION.

CHAPTER I.

WHAT SORT OF PEOPLE THEY WERE.

"MARIGOLD!" cried a loud voice, rough in tone, as working-men's voices are sometimes apt to be.

"I'm coming, father."

There was a pause, but no Marigold appeared; and Josiah Plunkett set down his bag of tools with a decisive bump, which showed disapproval. He was undersized as to height, but broad in build, with long powerful arms, and a large good-humoured face. Even when he frowned, as at this moment, the look of good humour did not vanish. Like most of his sex, he had a particular dislike to being kept waiting. Of course, he often kept other people waiting, and thought nothing of it; but to be made to wait himself was a different matter.

"I say! Mari-gold!" he shouted, with a vigour which made the walls of the little house to ring.

It was a very small house, a mere rattle-trap in build, with lath and plaster walls, from which paper peeled and damp exuded, and into which no nails could be driven with the least prospect of remaining there. Josiah Plunkett, being a carpenter, had done the best he could for the inside of his home under the circumstances; but he could not make a good house out of a bad one. Such untidiness as existed was not his fault.

"What's that noise for?" demanded a sour voice, and a woman appeared in the passage.

She was taller than Plunkett, and sallow skinned; not thin in figure, but thin in face, while from the acidity of her expression, it would seem that all the sweetness which once existed in her had been turned to vinegar. There is always some original sugar in everybody's composition, but the sugar does not always keep its sweetness.

"What's it all about?" she demanded sharply.

"What about! It's about me!" declared the husband. "Now, you just look here. I've got to be off, and I want some'at to eat. I haven't a minute to lose."

"Well, there's nothing ready for you, nothing at all!" Mrs. Plunkett spoke as if rather gratified to be able to say this. "You said you'd go and pick up something at the coffee-stall, to save the long tramp back; and you know you did. We've had our dinner—just scraps—and I didn't get anything fresh, and we've finished everything. There's no cheese, nor bread, nor nothing left—only a bit of butter."

"You might as well make short work with what you've got to say, and not go on for ever like the clapper of a bell," said Plunkett. "That's a nice tale for a hungry man, ain't it? Where's Marigold?"

"Mary's up—"

"Now, I say!—You, Jane!"

"Well, I never do bother to call her nought but Mary, unless you're by. Don't mean to, neither. It's ridiculous."

"She's not Mary, I tell you—she's Marigold. And Narcissus ain't Ciss, she's Narcissus. That's what they was christened, in full—Marigold and Narcissus—and I won't have 'em called by any other names. If they'd got common names, you'd go out of your way to make 'em uncommon. Women's that perverse!"

"If I was you, I'd be ashamed to have my girls called by such outlandish names. It ain't respectable. The very lads in the street calling out after 'em."

"They'd best let me catch them at that!"

"Well, it's no kindness to the girls, anyway; and Ciss cries."

"Narcissus is a little goose. Marigold don't cry. Marigold's got more stuff in her. Now, I say, you be sharp, and get me something. I'm famished, and I've got to work late; for I've promised Mr. Heavitree faithful as I won't leave that schoolroom till the work's done, and there's a lot to get done."

Plunkett followed his wife's retreating figure into the kitchen, and took a look round. It was not very tidy; not such a kitchen as he had been used to all his earlier married life, when the mother of Marigold and Narcissus was living. She had died four years earlier; and about two years and a half after her death, or eighteen months before this time, Plunkett had married again.

When first he brought home the new wife, people thought that he had made a good and wise choice, and that she would be a true friend to his two girls. She was a fine-looking woman, rather stout, almost handsome, with pleasant smile and manner, careful as to her appearance, and, indeed, rather fond of dressing well. The girls showed very nice feeling, welcoming her for their father's sake, and for a time all went well.

Then a gradual and extraordinary change came over her. She grew miserably gaunt and plain, untidy and careless, fretful and unhappy. What had caused the transformation, nobody knew; her husband least of all. She was plainly not in good health, seeming at times to suffer much, and talking of "rheumatism"; but she would not or could not say where the pain was, and she utterly refused to see a doctor.

Beside all this, she developed a grumbling and discontented temper, which might or might not have belonged to her in earlier days. It did not come to light until more than three months after her marriage. During those three months all had been smooth, and the girls were growing fond of their stepmother. Plunkett congratulated himself on the step he had taken; friends and neighbours said what a good arrangement it was. Then came the alteration in her, which altered the home, and cast a shadow on the lives of those who lived with her. One ill-temper in a house is quite enough to mar the happiness of the whole family.

Plunkett, reaching the kitchen, where pots and pans, plates and cloths, lay about in a haphazard fashion, dropped or rather plumped down on a chair, and stuck out his two legs in front of him.

"Now, then! Look sharp! I've got no time to lose."

Mrs. Plunkett slowly poked up the decaying fire, and placed a kettle thereon. Her husband watched with attentive eyes, which could never be otherwise than good-humoured, whatever tone of voice he chose to speak in.

"Now, then! What's that kettle for?"

"I thought you'd like a cup of tea, as I haven't got—"

"Cup o' tea, when I'm famished for want o' some'at substantial. I like that, I do! I'm to work like a slave, and have a cup o' tea to keep me going. Here's Marigold and Narcissus. Nice state o' things, ain't it, girls? Here am I come home to dinner, and not a scrap o' victuals for me to eat."

"Why, it's father," said Marigold.

She looked about seventeen years old, perhaps eighteen, and was not remarkably pretty; but what of that? Most people are more or less pretty in the eyes of those who love them; and as for those who do not, it matters little. Some girls think a great deal of having strangers say, "What a pretty face!" But when the stranger has said the words, and has passed on, forgetting, what has the pretty face gained?

If Marigold were not strictly pretty, except as seen by loving eyes, she was not without her charms. She had a neat figure, and rounded rosy cheeks, and her brown hair was smooth as satin, and when her light grey eyes smiled, they were full of sweetness. The mother's tidiness had descended in full measure upon her eldest daughter. Everything about Marigold seemed to have just come out of a band-box.

Narcissus, though eighteen months the younger, was the taller; a pale-faced girl, too colourless and thin, and too much disposed to stoop, for good looks. She had light-tinted hair, and rather listless eyes, suiting her listless manner.

But Josiah Plunkett admired his girls with all his heart—both of them in different ways; and Marigold the most, because of her likeness to his first wife. He might be rough in speech, and not too mannerly in manners; yet he really was a loving father, and he did not believe there were any two girls in the world equal to his Marigold and Narcissus. He was ready to back them any day against all the young women in the neighbourhood, for sense and niceness. So he often told his wife; but at the present moment he was too hungry for compliments.

"Not a scrap of victuals for me to eat! See, Marigold, what's to be done? I've got no time to lose. There's a lot of carpentering yet in the schoolroom, and I've promised Mr. Heavitree I'll get it all done to-night."

"Why, father, you said you wouldn't come back to dinner."

"That's what I've been telling of him! And then to be expecting a reg'lar spread, waiting for him on the chance!" complained Mrs. Plunkett.

"Well, if I didn't mean, I've changed my mind; and now I've got to eat. A cup o' tea ain't enough for my inside, without there's some'at more substantial to be washed down."

"Father, you wouldn't mind two nice fresh eggs! They've got a lot next door; and they'll lend me half a-loaf. Eggs don't take long to boil. We're out of cheese, but there's butter."

"Well, well, I shouldn't wonder if I could make shift with the eggs. Get three when you're about it, my girl; and be quick."

Marigold vanished swiftly, and soon came back, eggs in hand, nice big brown ones, appetising in look. The neighbours kept fowls in their little back garden, and had often an abundance of eggs to use or sell.

Why do not English working-men and their wives oftener keep fowls? The outlay and trouble are not great, and it would be well worth their while. Enormous quantities of eggs come to England from abroad; and the money which pours out of England to pay for all those foreign eggs might just as well be poured into English pockets for English eggs, if only fowls were more plentifully kept. Of course, people need to learn how to manage their fowls, how to feed them economically, and how to balance the good and bad times of the year, so as on the whole to be gainers.

"What's that there dirty saucepan lying on the chair for?" demanded Plunkett, as Marigold gave the eggs to Mrs. Plunkett. She would have cooked them herself, but the elder woman stood guarding the fire.

"It's been all the morning," murmured Marigold.

"Well, why don't somebody clean it, and put it away? Eh? That's what I want to know."

"I'd do it, if I might, father."

"She's not a-going to meddle with me nor my work. So there!" spoke Mrs. Plunkett aggressively, dropping the two biggest eggs into a saucepan, and keeping back one.

"All three!" ordered Plunkett. "I'm famished, I can tell you! What's an egg to a hungry man—eh?"

"Mother, that water don't boil," said Marigold.

"You just mind your business, and I'll mind mine," said Mrs. Plunkett.

Marigold gave her father a look, and he returned it with meaning. Hers said, "You see, I can't help myself!" His said, "What next, I wonder?"

Then Marigold brought out a clean cloth, and spread it neatly on one end of the kitchen table. Bread and butter, plate and cup, followed. Plunkett watched her with satisfaction.

"That's something like!" he said. "Them eggs ain't ready yet!"

"They're boiled," said his wife; and she brought them.

"There! I told you so!" Plunkett gave a sharp tap with his spoon, and thin liquid spurted from the crack. "'Tain't begun to be cooked. Here, Marigold—you know how! Put 'em in again, and boil 'em properly. Not you, Jane! Marigold!"

Plunkett raised his voice, and his wife retreated. Marigold did not wish to show any triumph, but perhaps she looked rather too well pleased, as was natural, though not wise. She covered the crack with salt, brought the water to boiling pitch, and dropped the eggs lightly in. This time the venture was successful.

"I've been having a talk with Mrs. Heavitree," said Plunkett, taking a gulp of tea.

"What about, father?"

"About Narcissus. Mrs. Heavitree wants to have her for a year—now. Not to put off no longer. She said she thought Narcissus was turned sixteen, and I said, yes, she was. So then she said, now was the time. The nursery girl is leaving next week, and Mrs. Heavitree thinks that 'ud suit Narcissus better than house-work. And I've promised she shall go."

"Rubbish!" said Mrs. Plunkett.

"May be, or mayn't be. That's neither here nor there. Anyway, I've given my word. I promised the girls' mother I'd let 'em go, each in turn, and I'm not a-going to draw back from that for nothing nor nobody. And I've promised Mrs. Heavitree, too."

"She's not going, though."

"She is going," said Plunkett.

"It's rubbish, I tell you," repeated his wife. "And what's more, it can't be. I can't spare Ciss. She's a deal more use to me than Marigold. Mary likes her own way a lot too much."

"Most folks do. Anyhow, you've got to manage. I've promised, and I'll stick to my word. Narcissus 'll go next week."

"I don't mean her to."

"She'll go, all the same. I don't want to part with her, but I'm not the man to go back from my word. I've promised, and I'll do it." Plunkett took another large mouthful of bread, and another huge gulp of tea. "Look here, you just talk it over with the girls, and see what's wanted. Caps and aprons, and all the rest. Marigold knows."

"I wish I was going!" said Marigold.

"Can't spare the two of you at once! You'll be a good girl, and help your mother. And Narcissus 'll be as happy as the day is long. So now that's all settled, and what do you think? I'm going to take you both to-morrow to see the wild beast show."

CHAPTER II.

SERVICE.

"THE menagerie! O father, will you?" cried Narcissus. "I do want to see the lions and tigers, and they'll be here such a short time. But mother said you wouldn't think of it."

"Throwing away money on foolery," murmured Mrs. Plunkett.

"The beasts ain't always such fools as men and women, after all," quoth Plunkett. "Anyway, they're worth looking at. I do believe Narcissus has never seen a tiger in her life. There hasn't been a beast show here since I don't know when."

"Since I was so high," Marigold said, putting out her hand. "Narcissus was too little, but I went, and I haven't forgotten. Only there was no elephant that time, and they've got one now—such an enormous creature!"

"Narcissus won't be called by her name at the Parsonage," broke in Mrs. Plunkett. "I know that. It's no name for a servant."

"The name's given, and it can't be ungiven; Narcissus she is, and Narcissus she'll have to be all her life through. If you'd ha' been my wife sixteen years agone, why then she'd have been Betsy or Jane, as like as not. But you wasn't!"

"They 'll call her Betsy or Jane at the Parsonage, you'll see."

"Shouldn't wonder if they didn't do nothing of the sort. Anyway she's going. I've promised, and she's got to go." Then in an undertone to the girls, "All right about the beast show!" And losing no more time, he went off.

"Well, I say it's rubbish, and I don't care who I says it to," observed Mrs. Plunkett. "Sending a girl away for a year, just when she's beginning to be useful. And how I'm to manage—"

"I shall be more useful when I come back, mother."

"No, you won't. You'll be full of notions, like Marigold; and set on your own way. I know that. I like you a deal best as you are,—a girl that'll do as she's told, and ask no questions. Marigold is for ever meddling in what don't concern her; and I don't mean to stand it. I wish Mrs. Heavitree would just let folks alone."

Marigold presently stole away to an upstairs room; and Narcissus slipped after her.

"I'm glad to be going. I didn't feel sure at the first moment, but I'm glad now," said Narcissus. "Mother does worry so; and you say Mrs. Heavitree isn't hard to please."

"Never hard. She does expect the work to be done properly. She works a lot herself, and she means others to work. Oh, I don't mean that she sweeps and dusts, though she wouldn't be above that if there was need; but she's always seeing after everybody and everything, and thinking and planning, and doing kindnesses, and looking to the poor. Mrs. Heavitree's never idle; and she never gives in so long as she's got the power to go on. You like her now, and you'll like her ever so much better when you're in the same house."

"I don't mind if she doesn't scold. It's being scolded I mind."

"You won't have that to bear, for she doesn't scold. She'll tell you if you do wrong, but she don't scold. I only wish I was going too, and I would if it wasn't for father. He'd be miserable if he hadn't one of us. I can't think what in the world has come over mother in the last year. Why, when she first came, she was as different! She couldn't be just the same as our own mother, of course; but she did seem nice; and now—"

"There's no getting along straight," said Narcissus. "Everybody is wrong, and everything goes crooked. There! She's calling. One of us has got to answer."

"I'll go. Don't you mind. I'll run," said Marigold, suiting her action to the word. She had a peculiarly light way of going about, a quick noiseless step and capable manner, such as one sees in a well-trained servant. Mrs. Plunkett walked heavily, and Narcissus did everything in a limp style; but it was a treat to look at Marigold.

The first Mrs. Plunkett had been, before her marriage, a very efficient servant; and she had done her best to train her girls well. Nobody can do so much as a mother in that line. If the early home-training in cleanliness, order, diligence, good management, be absent, later training will seldom entirely take the place of it. When mothers carelessly allow children to waste their time, to grow into untidy and dirty ways, they little think how hard they are making it for those children to become afterward either good servants or good wives and mothers.

But these girls had had the advantage of good early training. They had never been allowed to go about with soiled hands and faces, nor with torn clothes. They had been taught to darn and mend well, to scour and clean thoroughly, to put everything away in the right place directly it was done with, to keep the house always neat, and to do unhesitatingly whatever needed to be done.

Marigold had profited the most by these instructions, because she was the older, also because she was the more spirited and firm in character. Narcissus was not very energetic naturally, and as the youngest, she had been just a degree spoilt; still she was a gentle-mannered nice girl, generally liked.

In addition to early training, Marigold had had the advantage of a year in the family of the Rev. Henry Heavitree, Incumbent of St. Philip's, a church outside the town beyond the farther extremity, a good two miles off. Mr. Heavitree was son of the lady in whose house the first Mrs. Plunkett had been for many years a servant, and his wife gave herself a great deal of trouble in training young girls for service, preparing them well and wisely, showing them how to put their heart into their work, and to make a duty of it all, by doing everything as in the sight of God.

Mrs. Heavitree had always promised the first Mrs. Plunkett that, when Marigold and Narcissus should be old enough, she would have them at the Parsonage, each for a year's training. Plunkett himself did not greatly care for the plan, since he was loth to part with his girls, and he was not one to look far ahead into their future; but the wiser mother wanted them to be fitted to make their own way in life, whenever need should arise. She knew well that for domestic service, as for every other kind of service, preparation is necessary. A good housemaid or parlourmaid can no more be turned out ready-made, at an hour's notice, than a good soldier or a good business man. Success in any manner of life has to be worked for, through steady learning and steady practice.

Some people dislike the word "service," as if there were something lowering in the term. Yet who is there in this world, worth anything at all, who does not serve somebody? The husband serves his wife, and the wife serves her husband. The mother serves her children, and the children serve, or ought to serve, their mother. The clergyman serves his flock, the statesman serves his country, the Queen serves her people; and the very motto of the Queen's eldest son, the Prince of Wales, is "Ich dien," which means "I serve." And, to go far higher, we know that ONE, Who lived among men, One Who is Himself the LORD of lords, said to His disciples: "I am among you as he that serveth."

So when we speak of service, whether domestic or any other kind, we speak of that which may be beautiful and grand, because Christ Himself came among us as a SERVANT.

Though Plunkett did not so clearly as his wife see the need for his girls to be trained, yet he gave in to her judgment; and before she died, he promised that her wish should be carried out.

It was not until nearly three months after his second marriage, when things still seemed fair and pleasant in the little home, that Mrs. Heavitree reminded him of this promise, and asked for Marigold. Plunkett grumbled, but did not resist, for he was not a man to fail in keeping his word. He held to it scrupulously, indeed; allowing Marigold to spend a whole year at St. Philip's Parsonage.

Mr. Heavitree was a man comfortably off in point of money, far more so than is usual with clergymen. Not that the living was a good one. Had he had only the little stipend of St. Philip's to depend on, he would have been a poor man; but having private property of his own made all the difference.

Nothing delighted him more than to spend much of this property for the good of his parish; not by giving to lazy beggars who ought to have worked for themselves, but in helping the really needy who could not work, the aged and the sick especially; and in making countless improvements in schools, almshouses, etc.

Mr. Heavitree's was often called "a model parish," everything in it was so beautifully managed, and so well worked.

His wife lent an active helping hand in all these things; and in addition, she made the training of young girls her especial work. The Parsonage was large, and she had several children. While keeping two or three good old servants, she used to have a succession of young ones, as housemaids and nursemaids, constantly taken in, taught their duties, and passed onward to other places. Those who know the worry of young and untrained maids in a large household, where everything goes like clockwork, will appreciate the self-denial of Mrs. Heavitree in undertaking such a task.

Marigold went to the Parsonage three months after her father's second marriage, remained a year, and came home just about three months before my story begins—came home to a changed household, because of the change in Mrs. Plunkett. In the three months before she left home, all had gone smoothly; but now she found herself in an atmosphere of fretting, of worry and ill-temper, of disorder and carelessness, of all that in a small way could make life hard to bear.

She had heard something of this before, but not much. Mrs. Heavitree had not encouraged perpetual running home; while Plunkett and Narcissus had resolved to say as little as might be.

Now, however, when Marigold was living at home, the transformation became clear, and the new variety tried Marigold greatly.

The contrast between home and Parsonage proved severe. Everything there had been cheery and bright, the whole household in perfect order. Each person had his or her own duties, and was expected to do them well. To pass from such a state of calm regularity, order, and kindliness, to a house where all was mess and muddle, where things were used and set down anywhere to be left unwashed for hours, where a white tablecloth for meals was thought too much trouble, and where not a smile lightened the day's duties, Marigold felt acutely. She had been used to so different a condition, not only in the past year, but during all her life. It was not the smallness or the comparative poverty of home which distressed her, but the lack of order and of prettiness.

Marigold at first threw herself into the breach, so to say, and tried to improve matters. She washed whatever wanted washing, put away whatever was left lying about, scoured and scrubbed, dusted and swept, endeavoured in all ways to bring back the home to its olden state.