The Making of a Woman

Amy Le Feuvre

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

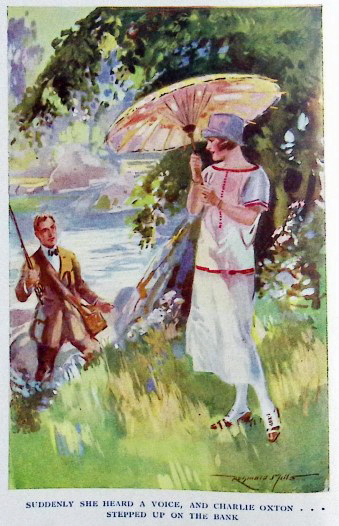

SUDDENLY SHE HEARD A VOICE, AND CHARLIE OXTON . . .

STEPPED UP ON THE BANK

THE MAKING OF

A WOMAN

BY

AMY LE FEUVRE

AUTHOR OF "PROBABLE SONS," "THE MENDER,"

"A BIT OF ROUGH ROAD," "HEATHER'S MISTRESS," ETC., ETC.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 BOUVERIE STREET, E.C.4

Made in Great Britain

Printed by Unwin Brothers, Ltd.

London and Woking

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

THE CHISEL

TOMINA IN RETREAT

BRIDGET'S QUARTER DECK

THE CARVED CUPBOARD

A DAUGHTER OF THE SEA

HEATHER'S MISTRESS

HER HUSBAND'S PROPERTY

JOYCE AND THE RAMBLER

THE MAKING OF A WOMAN

THE MENDER

ODD MADE EVEN

OLIVE TRACY

DWELL DEEP

A HAPPY WOMAN

THE CHATEAU BY THE LAKE

THE DISCOVERY OF DAMARIS

OF ALL BOOKSELLERS

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. A STAGNANT ATMOSPHERE

II. REBELLION

III. A SPEEDY RETURN

IV. A FRIEND IN NEED

V. A NEW LIFE

VI. DISILLUSION

VII. "SUNNIE"

VIII. "AN OUTSIDER"

IX. THE FIVE MARGARETS

X. CENTRES

XI. "WORTH SENDING FOR!"

XII. AN EVENTFUL RAILWAY JOURNEY

XIII. KINGSFORD FARM

XIV. CHARLIE OXTON

XV. A SUBSTITUTE

XVI. A DOCTOR'S VERDICT

XVII. TOWN FRIENDS

XVIII. SUNNIE'S MOTHER

XIX. SUCCESS

XX. TWO LETTERS

XXI. THE STRUGGLING PROFESSIONAL

XXII. IN DIRE STRAITS

XXIII. AN ARRIVAL

XXIV. THEIR FUTURE

XXV. LOOKING BACK

THE MAKING OF A WOMAN

CHAPTER I

A STAGNANT ATMOSPHERE

"God's silence on the outside of the house,

And we who did not speak too loud within."—Aurora Leigh.

SHE sat at her window overlooking the wide and dreary expanse of marshland. A faint streak of light near the horizon was all that could be seen of the sea. No trees or buildings broke the monotonous scene, and Jean's deep inquiring blue eyes sought in vain for anything to brighten her landscape. She was young, she was vigorous and healthy, and her spirits were good as a rule; yet to-day she was in the depths of depression, and the grey mist that was slowly rolling in from the ocean and obliterating the russet-brown rushes and the coarse dank grass that stretched for so many miles in front of her, only seemed a fit emblem of the cloud over her soul.

She threw up her head at last with a weary sigh.

"He is my grandfather!" she exclaimed aloud. "My father's father! But oh! If he had been my mother's father, how differently I should feel!"

She looked round her room, which was a large one, though barely and insufficiently furnished. Her eyes fell on a small oil painting on the wall. It was the portrait of her mother. The broad white brow, the delicately chiselled little nose, and sweet tremulous lips with their pathetic droop, and the deep earnest, soul-searching eyes, all combined to portray a sweet and beautiful woman. Jean inherited her mother's brow and eyes; her nose and mouth were more decided in character, her chin round and determined, and humour lightened the corners of her closely-shut lips. As her eyes met the ones in the portrait, she suddenly saw a scene before her. It had been enacted in this very room many years ago. A tiny curly-headed girl in black frock and white pinafore stood hugging a picture to her breast, and defying a stern old man before her.

"You sha'n't have my mother's picture! You've tooked her away from me and locked her up in a box, and she made this picture for mine own self, and I sha'n't give it to you! I shall grow up a big girl and paint millions of pictures—more than any one else in the world!"

The old man made a step forward, and the much-prized picture was torn from the child's tiny grasp. It was a pretty sketch of an old Italian châlet with a group of children gathering flowers in the foreground. On the floor were various bits of paper and a box of paints. Mr. Desmond had surprised his little granddaughter in one of her first efforts to follow in the steps of her artist mother. She had been happy all the morning with one of her mother's paintings before her, and had with untiring zeal been attempting to reproduce it upon scraps of writing paper. Much paint on fingers and pinafore was the result, also certain daubs of colour on the paper that meant much to her small mind, but very little to any one else.

"Listen to me!" was the wrathful exclamation as the old man, picture in hand, towered above her. "My son disgraced himself by marrying your mother. He could have allied himself with the oldest family in the county, and he refused. He died a beggar in Italy, and sent me his wife and child to support. I took you in for his sake; you bore his name, and when your mother had the audacity to sell her paintings with my son's name upon them, I forbade her to touch a brush or pencil again as long as she was under my roof. She obeyed me, and now that she is dead, am I to stand still and see you strive to make yourself perfect in the art that bewitched and ruined my only son? Who dared to give you pencil and paints?"

The small child was not awed, as her mother had been.

"I shall draw pictures every day, and you're a wicked man, grandpapa! Nurse did buy a paintbox for me, and if you take it away, I shall paint out of your ink-pot! I will! I will paint pictures like mother did!"

Jean smiled as she thought of the small fury dancing up and down, but she frowned when she recollected the summary chastisement that followed, and the consequent collapse and penitence of the motherless little one.

And then her mind left the past and dwelt in her present.

It was a very grey monotonous one, but there were gleams of brightness in it. She lived alone with her grandfather in an old stone house on the border of the marsh. For five years, she had been to a small private school in the neighbouring town, about nine miles away, and then at seventeen, her education was supposed to be complete. She came back, and was installed as her grandfather's housekeeper and companion.

She was fond of music, but there was no piano in the house; a great reader, but the only room that contained any books was her grandfather's library, in which he sat and dared any one to molest him. Drawing and painting were forbidden pastimes. At school, she had envied her fellow pupils who used to attend an art school close by; but, though she had never had a lesson, and in spite of her grandfather's prohibition, she was seldom without a pencil and sketch-book. Beauty in any shape or form intoxicated her; her lesson-books had not a margin that was not covered with faces and forms of all descriptions. When she returned home, she never rested till she had copied her mother's portrait, and as she traced the delicate, pensive features, her whole heart went out in love to her young mother, whose spirit had been crushed and broken by the tyranny of her father-in-law. When that occupation was finished, Jean looked around her, wondering how she would pass her time.

Four elderly servants formed the household—two men and two women. John and Mary were husband and wife; John was butler and valet to Mr. Desmond, Mary the cook. Elsie was the housemaid, and was a soured, miserable woman through numerous misfortunes in her life—chiefly the iniquities and treachery of some of her early lovers. Rawlings was gardener, and was the most cheerful individual of the community.

"Are you feelin' low?" he would say. "Come into the open air and it will blow away your feelin's!"

It was in the garden that Jean eventually spent most of her time. She learnt the times and seasons of every plant and flower from the old man; she was initiated into the mysteries of grafting, potting, and pruning. There was not a big flower garden; the wind swept over the lawn, and the salt spray stunted and burnt the trees and shrubs. It stood in the front of the house, unprotected from the open marshland, but the kitchen garden behind was encircled by four high walls, and it was there that Jean and Rawlings talked and worked together.

But lately the stormy spring weather had laid Rawlings low with an attack of rheumatism, and Jean had shunned the garden.

She had taken the opportunity to steal into the library when her grandfather was interviewing a tenant of his in the servants' hall. And when he returned, she was too deep in a volume of Scott's poems to notice his approach.

He looked at the girl as she sat on the floor by his bookcase, her head resting against the books behind her, and her lap full of odd volumes she had been glancing at. And then, harshly, he brought her out of the stirring scenes of battle and of love in which her soul was feasting.

"Did I give you leave to touch my books?"

Jean started to her feet and faced her grandfather with sparkling eyes.

"No," she said with spirit, "but I am hoping every day that you will. Grandfather, I cannot live this life much longer. You are starving me whilst you are surrounded with plenty. Let me share some of your books with you."

Mr. Desmond stooped and took up the book that she had laid down.

"Poems!" he sneered. "When a woman surfeits herself on romances and poetry, she lays the foundation for worse to follow. No, Jean; keep to your own province and let me keep to mine. Books are for men, household tasks for women. Let Mary teach you to cook a dinner, and Elsie to mend the house-linen. And never let me find you in this room again, unless I send for you!"

"But," argued Jean, stung to the quick by the contempt expressed in her grandfather's tone, "I have a brain as well as you. You don't want two cooks in the house nor two women to mend the linen. I have nothing to do these wet days. If you will not let me read your books, give me money to buy some myself. You will hardly let me read the newspaper. I shall turn into an imbecile, if I am treated like this! Oh! If I had money, how different my life would be here!"

Passion was in her tone. He waved her away like a naughty child.

"I clothe you and feed you. You want no more."

But Jean would not be dismissed.

"Grandfather, if you do not let me read, I shall paint. I shall make it my occupation in life."

The old man glared at her.

"If I ever catch you at it," he roared in fury, "I'll cast you out of this house for ever!"

"Perhaps," muttered Jean, "that would be the best thing that could happen to me!"

She left him, and went up to her room.

Would life always be like this? she wondered, and sitting at her window, gloom descended on her soul. Then she went to her bookcase and discontentedly viewed its contents. A Bible, a prayer-book, and a dictionary, half a dozen children's story books, and Boswell's "Life of Johnson." The latter was the only prize she had earned at school, and she had read it through already five times.

"If only I had money of my own!" she sighed. "I wonder if I could by any possibility earn any!"

Then she started up. "I will go out," she resolved; "as Rawlings says, it will 'blow away my feelin's'!"

She put on her thick coat and hat, and in a few minutes was treading the flat dreary road that led by the side of the marsh to the nearest town.

It was already getting dusk; a flock of wild ducks suddenly rose close to her, and flew screaming over the marsh towards the sea. There was no wind; the croaking of frogs seemed the only sound that broke the monotonous silence. She looked around her with keen alert eyes, but her gaze fell on stunted gorse bushes, and beds of the green rushes that were so familiar a landmark in this part of the country.

"Oh!" she said impatiently to herself, as she threw back her head with a quick, imperious gesture, "I know this all so well, that I could paint it with my eyes shut! It's a deadening part of the world to live in. Stagnant life, and I am beginning to think that mine is like it!"

Then she looked eagerly in front of her. Two figures were walking towards her. One of them she recognised. He was a friend of her grandfather's, who lived about three miles away at his place called the Hermitage, and on account of his quiet and studious habits was nicknamed "the hermit" by his acquaintances.

Mr. Desmond had a good many friends in the literary world, and it was of no uncommon occurrence for two or three men suddenly to turn up and dine and sleep with no previous intimation of their arrival. Jean often wished women would accompany them, but this was never the case. Old Mr. Desmond looked upon the weaker sex as being utterly unfit to converse intellectually with learned savants. He had never been a society man. His wife had died four years after his marriage, and since her death, he had become entirely absorbed in his books. Jean never had much to say to the men who frequented her grandfather's house. She took her seat at the dinner table, but did not see them afterwards. They looked upon her as a schoolgirl still, and were like her grandfather, more interested in science than in women.

Mr. Railton, "the hermit," was the one she knew and liked best. She quickened her pace, and a bright smile came to her lips as she greeted him.

"You are taking a constitutional," he said in his grave courteous manner. "I was bringing a friend of mine to see your grandfather this evening. Let me introduce him to you—Colonel Douglas. He has just come home from wanderings in Persia."

Jean held out her hand. "Then, you are sure of a warm welcome from grandfather," she said, "for the East is his pet part of the world."

As she gazed at the newcomer with some interest, she was conscious of an amused scrutiny in his eye. He was a tall well-knit man, with bronzed face and dark hair, and a certain humorous twist of countenance softened the otherwise stern ruggedness of feature.

"Not quite so dry and old as most of them," she thought, and she noted with appreciation his attire which, though irreproachable for a country gentleman, had a smartness and up-to-date appearance that was not usual amongst her grandfather's friends.

"And what is your favourite part of the world?" asked Colonel Douglas. "This?"—with a wave of his hand over the desolate marsh.

Jean was quite taken aback. She was not accustomed to be asked what were her likes or dislikes. She looked up at him earnestly.

"I should be happy anywhere away from this!"

A hidden fire and passion leapt to her eyes as she spoke, then she passed on, and the two men went their way.

"A sleeping volcano," said the Colonel. "Who is she?"

"The only granddaughter of Desmond—a good little thing in her way, I believe. She has not long been home from school. It is a dull life for her."

They commenced to talk of other things.

Jean soon came to a standstill.

"Of course, they're coming to dinner. I wonder if Mary knows. I don't believe she does. Mr. Railton won't make any difference, but this stranger—he is accustomed to good dinners, I feel sure; I think I will go back and warn her."

CHAPTER II

REBELLION

"We would be free as Nature, but forget

That Nature wears an universal law,

Free only, for she cannot disobey."—H. Coleridge.

JEAN was not quite so silent at dinner that night. Colonel Douglas told such entertaining stories, and deferred so often to her, that she surprised her grandfather by expressing opinions of her own. He snubbed her unmercifully more than once, but she did not as usual sink under it.

"You must come out to Persia, Mr. Desmond," said the Colonel gaily, "and bring your granddaughter with you. Travelling is made so easy nowadays for ladies. I have been asked to conduct a party through Egypt and Palestine. Shall I undertake you?"

Jean caught her breath, but her grandfather shook his head.

"I am too old to travel."

Colonel Douglas turned to Jean.

"Miss Desmond, can I not persuade you? My sister, whose husband is in India, will chaperon you with the greatest pleasure."

Jean looked across at her grandfather audaciously.

"Shall I go, grandfather? You do not want me here."

Mr. Desmond's brows lowered threateningly.

"When I do not want you, I will let you know," he said coldly.

Jean's eyes flashed.

"I shall paint a picture and get my liberty," she muttered to herself, and this resolve took hold of her, and remained with her to such an extent, that she lost all interest in the ensuing conversation.

Colonel Douglas glanced at her more than once, and noticed the absorbed dreamy look in her eyes. She left the dinner table, and did not see the gentlemen again that night, but upstairs, she was pacing her room with feverishly clasped hands and flashing eyes.

"What could happen, if he turned me out of the house? Where could I go? Would he give me any money? I'll begin to paint to-morrow. I will, I will! He couldn't turn me out of the house to starve. He would give me some money, and wash his hands of me, and I—where could I go? Why, the whole world would be before me. I would be able to go this tour in the East, and take my chance of what happened afterwards."

When she went to bed, she did not sleep. Visions of what might be, rose before her. Wandering beneath date-palms, and a cloudless blue sky; sleeping in white tents, with camels and mules and swarthy Arabs around her, sailing slowly up the Nile seeing strange sights every day, perhaps climbing the Pyramids and viewing the mysterious Sphinx. It all fascinated and enthralled her.

"I should be in a world of beauty and of art, and be surrounded with nice, friendly women and men. I should be able to give myself up to painting and to reading, and I should live, live, live!"

When the morning came, calm common sense battled with her impulsive excitement. She almost cried with vexation when she found her paintbox nearly empty, and not a piece of canvas or paper in her portfolio. But she would not be deterred from her purpose.

"I shall do nothing rash," she argued with herself, "but paint I shall, and as I have no money I shall beg, borrow, or steal. And yet—yet—it is all so hopeless. What should I do if my only relative cast me off? I can but wait. A change must come in my life, sooner or later. I will go out and talk to Rawlings. He is better, so will be in his beloved garden again."

She found him sowing seed. He looked up with a bright smile at her as she came.

"Eh, Miss Jean, 'tis good to be in the air agen. I have been giving thanks with the birds."

"You're always giving thanks, Rawlings. I wish I had any luck to thank for."

Jean balanced herself on the side of a cucumber frame, and looked about her with discontented eyes. It was a fresh clear morning, and the sun was streaming through the swiftly-passing clouds. The old kitchen garden, with its deep red walls and box-edged borders, was full of fresh young life, and Jean's fretfulness passed away.

"I shall make a picture of this garden," she said joyously, "and shall call it 'old age and youth.'"

"Meanin' you and me?" queried Rawlings, dubiously.

"No, I was thinking of the garden itself. How many lives have lived and died in it, Rawlings—vegetable life I mean!"

Rawlings shook his head.

"I've sowed here these twenty year or more. 'Tis a wonderful fruitful spot. But there, Miss Jean, I always hold there be no such thing as dyin' in Gods Kingdom. The plants live on in their seeds, and come up year by year; same in the bulb and root tribe, they bear life in them, whether buried or resurrected."

"I wish you were my grandfather, Rawlings; you would help me to blossom out and sow seed, wouldn't you? You wouldn't put me in a hole, and tell me to stop there, and prevent me covering as much ground as I wanted to. Grandfather would be a bad gardener, and how he would hate to see the wind come and scatter the flower-seeds in all directions! How I wish a wind would come and carry me off somewhere!"

"What is the matter with you, Miss Jean?"

"I want money, Rawlings—money to buy books and paints. How can I get some?"

He looked at her laughing face as she turned it up to his, then gave a dry little chuckle as he went on with his work.

"Books and paints be poor satisfaction for a discontented spirit," he observed. "I be happy without 'em, and so can ye be, Miss Jean."

"No, I can't!" she said, springing up and stamping indignantly with one foot on the ground. "I am starving, Rawlings, and I want to be fed!"

Then in another tone she asked—

"Have you ever been to London, Rawlings?"

"No, that I have not."

"Have you any friends there?"

"A married sister, Miss Jean, who did marry a man in the grocery line. She has ofttimes asked me to pay her a visit, but Lunnon be not to my taste."

"Where does she live, Rawlings?"

"That I can't tell ye, but the name of her house be 177, Charles Street."

Jean repeated this over softly to herself. Then she looked at some Neapolitan violets thoughtfully. Finally she went over to the frame and picked a large bunch of them, and then she ran off to the house, calling to Rawlings over her shoulder, "The wind has begun to blow, Rawlings."

An hour later, she was steadily walking along the same flat road that she had taken the day before, but there was purpose and determination in her face, and in her hand she grasped a small basket of fragrant violets. The town was reached at last, but as she came in sight of the shops, her courage failed her. She hesitated outside a greengrocer's, where flowers were displayed in the window; then squaring her shoulders, walked boldly in.

"Good morning, Miss Desmond," said the woman civilly. "What can I have the pleasure of serving you with?"

Jean became red and confused.

"I—er—don't want anything, thank you. At least I—have you any early potatoes yet?"

"Well no, miss. 'Tis too early. The spring be extra late this year—"

"Thank you—thank you—it isn't of the least consequence!"

Poor Jean dashed out of the shop, and then almost ran into the arms of Colonel Douglas. He started, then held out his hand pleasantly.

"Good morning," he said. "Have you driven in to shop?"

"I never drive," replied Jean. "I always walk."

Her cheeks were crimson, and she turned away her head; but not before Colonel Douglas's keen eyes had noted glittering drops on the end of her eyelashes.

"Splendid!" he said heartily. "There is nothing that does one more good than a thorough brisk constitutional, with a purpose at the end."

Jean's "purpose" nearly overwhelmed her now. Then in desperation she turned to him, shaking off her tears and diffidence.

"Colonel Douglas, will you help me? Buying and selling is only an honourable exchange, as my schoolmistress used to say. Do you want, do you know any one who wants some early Neapolitans?"

She held up her basket to him as she spoke, with a mixture of audacity and bashfulness that amused the Colonel.

He looked at the cool fresh bunch, with their sweet-scented fragrance, then quietly lifted them out of the basket and dropped half a crown in their place.

"This is a very honourable and pleasant exchange to me," he said, and raising his hat, he walked away.

Jean looked down at her basket, and then after him.

"I like him!" she mentally exclaimed. "He is a gentleman, and he isn't curious!"

Then she sped away to a stationer's and invested her one coin in a small quantity of paints and paper.

The walk home seemed short, but Jean nodded her head as she entered the house.

"It has been worth it, but I could never do it again."

She stationed herself in the kitchen garden that afternoon, and sketched old Rawlings amongst his cabbages with a true artist's delight. The old brick wall for a background, and the fresh green, with the sun upon it around the old man formed a pretty picture. She was almost disappointed that her grandfather did not appear upon the scene, but she was left in peace. Mr. Desmond seldom visited the kitchen garden, and had little idea how his granddaughter spent her days. A week passed. Jean worked on with a feverish excitement. Her scarcity of materials only made her more determined to persevere with the little she had. More than once her grandfather looked at her flushed cheeks and bright eyes, wondering at her animation.

"Jean," he said to her one evening after dinner, "I shall be absent a few days. I am going with Mr. Railton to town."

Jean looked up at him startled.

"Will you leave me some money?" she asked.

"I do not think you will need any. Mary manages the housekeeping."

"But, grandfather, I am penniless. It is dreadful to be kept so. Supposing I was out of doors and met with an accident, and had to go to an inn, or fell into a bog—or—"

Jean stopped her eager speech. She saw the ironical smile that she so disliked.

"Pray continue," Mr. Desmond said, "and give me a reasonable excuse for handing out some money to be squandered on ribbons and laces and sweetmeats!"

Jean's eyes flashed angrily, but her grandfather stopped her protestations by putting half a sovereign into her hand.

"Now what will you do with it?" he said, not unkindly.

Jean threw back her young head a little defiantly. "Feed my mind and heart," she said.

Mr. Desmond laughed.

"And what food do they require?"

"Books and paints."

The reply was prompt and unexpected. Mr. Desmond's brows contracted.

"You know my will about paints," he said.

Then Jean cast prudence to the winds. Her young, passionate soul swelled within her.

"Grandfather," she said, "you hate deceit of any kind and so do I. I have been waiting to tell you. I cannot keep from painting. It is no good. I believe it was born in me. I must do it; I have been painting a picture lately that I feel is the best I have done. I will show it to you if you like."

She darted from the room, returning very shortly with her treasure.

"There!" she said triumphantly as she held it out to him. "I know it is full of faults, but I have had no teaching, and if I can do as well without any help, what should I do under a master?"

It required no keen inspection to tell that Jean's little picture bore the marks of genius.

But she was quite unprepared for the paroxysm of fury that took possession of her grandfather. He seized the picture, and dashing it to the ground, stamped it underfoot. Then with an oath he turned upon her.

"Are you to be a perpetual taunt to me of my son's disgraceful alliance?" he roared. "Am I not to be master in my own house? Have I fed and clothed you all these years to meet with this insolent, ill-bred defiance? What did I tell you a short time ago?"

"That you would wash your hands of me, or words to that effect," said Jean, trembling before him, but steeling herself to withstand his anger. "You have housed and fed me all these years, but you have never loved me. I suppose I remind you too much of my mother. I want to go away from you. I cannot live on here and be kept from using the talent God has given me. As I must and will paint, I mean to go away. I want you to give me some money and let me go."

For a moment Mr. Desmond was taken aback by the girl's impetuous earnestness. But he was a passionate self-willed man who had never in his life been thwarted or contradicted by any of his household, and his temper was entirely beyond his control. He turned upon her in a fury, and Jean quailed before his violent words.

"Go to your room! Don't let me see you again until you are in a proper frame of mind. Do you think I am a man to be trifled with? Your mother brought evil into my family, and you are seeking to follow in her steps. I wish to heaven, I had cast her out when she first appealed to me! Your blood is the same as hers. I was a fool to think I could train you, and turn you out a respectable woman. Do you want to leave me? You can make your choice. If you won't obey, you can go and starve, for not one penny will I give towards your support away from me!"

This, interspersed with some very strong language, was the substance of his speech.

Jean fled up to her room frightened and angry, but not submissive. She did not see her grandfather before he left for London, and was very quiet for the next few days—so quiet that Elsie informed Mary that "the master had broken Miss Jean's spirit entirely."

"She locks herself up in her room for hours together, and walks about with her lips as grim as the master's."

"She is but a child," responded Mary. "She'll learn to give in to the master soon. 'Tis her high spirits that won't bear the curb."

CHAPTER III

A SPEEDY RETURN

"Those things that a man cannot amend in himself

or in others, he ought to suffer patiently

until God orders things otherwise."—Thomas à Kempis.

IT was a bright spring afternoon in town. Colonel Douglas was wending his way from his club in Pall Mall to his rooms in a quiet street off Piccadilly. He was due at his sister's house in Palace Gate at five, and he was inwardly pitying himself for the ordeal of sipping tea and making conversation amongst the society men and women generally to be found at Mrs. Talbot's "At home" days. His thoughts were somewhat after this fashion—

"Wish I could get back to the wilds again. And yet, after ten years' absence, England has an extraordinary fascination for me. I think I'll go into the country for a bit. It is restful, and I can work at my papers in peace. I am thankful that this personally-conducted tour will fall through. Women of fashion are too much responsibility for a single man. Wish Railton would come out."

Here a flower-girl thrust forward a button-hole of Neapolitans. He shook his head and walked on.

"That was a funny little episode down in that marsh country. Wonder what she was after? I should like to know how my half-crown benefited her. A bewitching little creature, with her rebellious longings after a wider life. Her grandfather is a Tartar at home, I fancy. I mustn't forget he has invited me down next week. He's a clever old chap. I quite enjoyed running up against him yesterday in the Museum. Think I shall make that my excuse to Norah for getting out of town."

He let himself into his lodgings with his latch-key, but his landlady appeared in the hall.

"If you please, sir, a lady is waiting to see you. I said I thought you would be in soon."

Colonel Douglas lifted his eyebrows.

"What name?" he asked shortly.

"She did not give her name, sir."

He opened his sitting-room door sharply, and when he confronted Jean, was too much surprised to speak. She stood up with no sense of the unconventionality of her action, only relief and hope seemed to lighten her face when she saw him.

"I was afraid I might not meet you," she said simply. "I got your address from Mr. Railton, for I didn't know it, and I want to know when you and your sister are going to start on this tour through Egypt and Palestine."

"I think it is knocked on the head," he replied, courteously. "My sister has cried off it, and I am not very keen on it myself. I suppose your grandfather is staying on in town. How do you like the change?"

He talked on, for he saw the blank look of dismay on Jean's face, and the rush of colour to her cheeks.

"I did not understand you were up in town. Are you seeing any of the sights, or does your grandfather restrict your dissipation to the British Museum?"

Then Jean found her voice.

"I am not with him. I have made a mistake. It is of no consequence. I thought your trip was settled."

She turned to the door with averted face, but Colonel Douglas caught sight of tears brimming over. He was puzzled and uneasy, especially when he heard her add, almost in a whisper, "I don't know what to do."

"Where are you staying?" he asked kindly. "Do I know your friends? At all events, let me walk back with you."

Jean hurried out of the house, then as she saw him by her side she swallowed her disappointment, and with an effort said—

"Thank you. I don't know London very well. I want to go back to Charles Street. I have left my grandfather altogether. I—I am staying with Rawling's sister. It's a long way from here—in the City, they call it. I came by omnibus."

"I am afraid you are in a difficulty, are you not? Let us take a hansom, and then you can tell me all about it."

"I do want help dreadfully," acknowledged Jean, when she found herself seated side by side with him in the cab. "But you're almost a stranger, and I expect you will think me half crazy."

"Indeed, I shall not. Two heads are better than one. Make me your father confessor."

He spoke lightly, but Jean drew up her young head proudly.

"I have done nothing wrong; at least, I hope I have not. Grandfather is hard and cruel. He has forbidden me to paint, he won't let me read. He told me I could leave him if I liked, and so I did. I left home yesterday. I thought perhaps your sister would take pity on me, and let me join this tour. I want to earn my own living; I shall have to. I have no money, but I know I can earn some. I mean to begin at once. Mrs. Toppings, Rawling's sister, is very kind; she has managed a bedroom for me, and they're most respectable people. I never found their house till ten o'clock last night—there seemed so many Charles Streets in London—but she took me in at once. And if I can't go with you, I shall try something else. I shall go to a registry office, and get a mother's help' situation, or companion. Oh, I shall do very well, I am sure. It is only just at first, and of course, I didn't know about you. I thought you lived with your sister, or had a wife. I hope I shall get on. I mean to. I never shall go back to grandfather again—never, never!"

Jean talked fast and nervously, and Colonel Douglas listened with a grave, quiet sympathy that soothed her. But he was greatly startled and perplexed, and concerned at the young girl's innocence and inexperience.

"My dear Miss Desmond," he said, when she paused for breath, "I have seen a little more of the world than you have, and I beseech you, to think of what you are doing. I am perfectly certain your grandfather would be most desperately anxious and distressed, if he knew that any hasty words of his had driven you to such an extremity as this. A friendless young woman in London will never be able to support herself. You little know the pitfalls for youth and inexperience. Have you no relations in town who might advise you?"

"I have no relations," said Jean, with a look of dismay in her eyes. "Not one, but grandfather, and he doesn't care for me; he doesn't want me. Oh, Colonel Douglas, I must paint! It is life to me! It is cruel to keep me from it!"

"Listen!" the Colonel said, trying to speak lightly, though he knew that this was an important crisis in the girl's life. "I am going to stay at your home next week, and shall not like it at all, if you are not there to welcome me. I promise you, I will do my best to persuade your grandfather to let you follow your beloved art. People say I have a knack at persuasion. I have tackled more difficult subjects than your grandfather in my time, and have come off conqueror. If you wish to study painting, you will want money. Your grandfather is the one who must give you that. Promise me to go straight home, and I venture to say that you and I together will be able to get round your grandfather. If you are quick, you will be able to catch the express from St. Pancras, and I will come and see you off myself."

"I can't! Oh, I can't!" exclaimed Jean, struggling with tears and mortification.

Colonel Douglas laid his hand lightly on hers. Jean often wondered afterwards whether there was mesmerism in his touch. Perhaps it was his tone as well, that made her yield.

"You can and you will, for you have enough determination and good principle to carry you through. Is this the house? I will wait in the hansom while you collect your luggage. Have you money to pay your landlady?"

Jean assented proudly. She went into the house as if in a dream, but very soon returned. Colonel Douglas smiled, as he saw her small handbag. But when she was driving to St. Pancras Station with him, she burst out passionately—

"Colonel Douglas, I shall never forgive you, if you don't help me to get away! I made my plans with such care. I hoped your sister might help me. I was counting on your taking this tour. I put all my trust in you, and you have utterly failed me. I shall never get over it, if you don't persuade grandfather to give me more liberty. I daresay you think me rash and foolish to build upon what you said at all, but when you bought my violets and never asked questions, it made me believe in you. I couldn't help it, and now you're shattering all my plans to pieces!"

"I am wanting you to build with bricks instead of cards," said the Colonel, smiling, and feeling it was quite impossible to help taking an interest in this impetuous unconventional little person. "You wait till my visit to you comes off, and then you will acknowledge, I have been your good genius."

Jean looked almost tearful when the train was starting. Colonel Douglas nodded brightly to her:

"Keep up your spirits. We shall meet again soon."

Half an hour afterwards, he was on his way to his sister's, and was severely reprimanded by her, when he arrived for his late appearance.

"Now, sir," she said to him when her guests had disappeared, and only she and her great friend, a Mrs. Gower, were left. "Give an account of yourself to-day. Why did you fail me?"

"An errand of—of mercy kept me," said the Colonel, leaning back in an easy chair and looking at his sister with a humorous twinkle in his eye.

"I was sure of it!" young Mrs. Talbot exclaimed, turning to her friend. "There never was such a man for laying himself out for impostors. He always has been like it, Jessie, from the time he was found helping a drunkard into a public-house when he was four years old. 'Poor man is firsty!' he explained when his nurse dragged him off. Some one told me he was nicknamed in his regiment 'The humbug's hope.' Last week, he was accosted by a German female in the streets. She had landed that day in a strange country, she said, and she had lost her purse. She appealed to the 'Herr,' for she said she saw 'honour in his eye.' Don't laugh; that was a fact. He told me so himself—didn't you, Phil?"

"Our feelings were mutual," said Colonel Douglas, smiling. "I saw truth in her eye."

"Do tell us about your case to-day," Mrs. Gower said, trying to restrain her laughter. "You have such a self-satisfied expression that I am sure you are convinced that you have successfully relieved distress."

"Yes," the Colonel said quietly. "I hope I have prevented disaster coming to an inexperienced child. If you promise to listen sympathetically, I will tell you about her, for I want Norah's help in the matter."

In a few brief words, he laid Jean's hasty impulsive escapade before them, and for a wonder, his sister did not laugh. She grew keenly interested. "Poor little soul! Why didn't you bring her to me? How can a man try to manage a girl in these days! I mean her grandfather, not you. Does he not see that forbidding her to touch a pencil or brush is the very way to stimulate her to do it? What brutes men can be! Is she a presentable little creature, Phil? Would she like to come up to town and pay me a visit?"

"That would do her no good."

"Thank you! Perhaps you will tell me how I can help you, then?"

"I think," said the Colonel slowly, "that if you know some quiet nice woman who would board her, and mother her, and let her attend some school of art or studio, I might persuade her grandfather to send her up to town for a time. She does not wish to go into society; her heart is in her work."

Mrs. Talbot shrugged her shoulders.

"I am too giddy to have the care of her! I have a great mind not to aid you in this business. But I do happen to know of the very person for her—Frances Lorraine."

"Frances Lorraine!" repeated the Colonel in wonder. "Is she in London? Has she left her old home?"

"She was turned out of it. It's the old story of the brother's wife supplanting the sister. Poor Frances has not much to live upon. She has taken a small house in Kensington, and asked me the other day, if I knew any girls or students who would like to board with her. She's just the sort of a person for a troublesome granddaughter. Cheery and sensible and not too prim. So when you tackle the irate grandfather, tell him she will uphold his authority through thick and thin. Frances always was a most uncomfortably conscientious person!"

Colonel Douglas smiled.

"She always had a knack of getting people to do the right thing, I remember. Well, it will be good for both, I believe, if we can bring them together. The grandfather is the chief obstacle at present."

And it was of her grandfather that Jean was thinking as she was whirled away in the train. She wondered if she should get home before he did, and whether the old servants had been perturbed at her absence. She had made her escape very quietly, putting a note on her grandfather's writing-table in the library. But she had taken no one into her confidence, and now as she realised the frustration of all her schemes she was glad she had not done so.

"It is dreadful going back! I wish I had not given in, but that Colonel Douglas is so determined, I felt I could not resist him. And I think it would have been just as dreadful staying on in London. I couldn't have done it, for I should not have had enough money. It was a mad idea! Thinking over it calmly now, I was silly to imagine it would turn out all right. I might have known it would be difficult—impossible to change one's life and slip into another so easily. How am I to meet grandfather? What can I say! Perhaps I may not have to tell him. And yet I must. I can't deceive!"

This was the substance of her thoughts. She felt very small as she alighted at the country station, and refusing the offer of the only fly, tramped sturdily along the flat highroad towards home. She could hardly believe it was only the day before that she had left it—as she thought then for ever—and as she gazed about on all the familiar landmarks she exclaimed—

"I do believe I am glad to see it again. That London seems a nightmare!"

Elsie met her at the hall door with a little scream of delight.

"Oh, Miss Jean, whatever have you been a-doing! We have been in such a state of fright about you. Rawlings had a telegram first thing this mornin' from his sister to say you were with her, but for pity's sake, don't be playing no such tricks agen. Master isn't back, but he's comin' to-night. He has stopped to dine at Mr. Railton's on his way from the station. What a blessing 'tis to see you agen, and how could you go up by yourself to that awful, wicked London! Why, I've heard awful tales of young girls disappearin' right away from the time they stepped out of the train, and never being heard of no more! Human nature is so shocking in big cities. I'll away to the kitchen to ease Mary's mind, and p'raps you'll tell us what you went for, when you've had some dinner. For you do look dead beat!"

Jean dashed upstairs to her room. Elsie's chatter was unbearable to her.

And when she had locked her door and saw everything in her room exactly as she left it, the humorous side struck her and she laughed aloud.

"How little I thought all my passionate longings for a freer life, my attempt to launch out into the world, would result in a journey up to London, a bad half-hour or so trying to find Mrs. Toppings' house, a meal and a bed there, and then to-day a journey back again! Not one glance at any of the shops, not a glimpse of a picture gallery. All a hopeless failure, but at all events, I have been saved the humiliation of being dragged back by grandfather. How could Mrs. Toppings be so treacherous! Yes, Colonel Douglas has saved me from that!"

She changed her travelling things, then sped downstairs remembering the note she had left on her grandfather's table. She found it in the same place as she had left it, and with a rueful smile she opened it and read it before she tore it up.

"MY DEAR GRANDFATHER,—I have left you. I feel I must use the talent that has been given to me. I shall do nothing rash, but would rather not tell you what my plans are till later on. I hope to make my fortune by painting. I don't expect to get rich suddenly, but I shall work my way gradually, and when I am independent I shall write to you again."

"Your affectionate granddaughter,"

"JEAN."

"I'm afraid," she said slowly, as she turned and left the room, "I'm afraid, I have acted like a fool!"

Then she rang the bell, and spoke with great dignity when John appeared.

"I hope Mary can give me some dinner. Ask her to send it up, as soon as possible."

"We'll do the best we can," responded John, looking at her keenly; "but you've put us about sorely, Miss Jean."

Jean was silent. When she had dined, she went out into the garden, but kept away from Rawlings. It had been a long day. She was determined to speak to her grandfather before she went to bed, but it seemed to her as if he would never return. At last she heard his footstep in the hall, and went forward to meet him.

"You ought to be in bed, Jean," were his first words. "Has everything gone on well during my absence?"

"I want to speak to you, grandfather," Jean said, quietly, though her heart began to beat rapidly. "I have something to tell you."

Her grandfather looked at her through his bushy eyebrows, and led the way to his library. For the time he had forgotten how they had parted, but he was beginning to recall it now.

"I should like to tell you what I've been doing," said Jean, throwing back her little head with more pride than submissiveness. "You remember how you spoke to me and what you said. Yesterday, I left this house, as I thought, for good. I went up to London."

Mr. Desmond glared at her in silence.

"I—I thought," continued Jean bravely, "that I might be able to go out to the East with Colonel Douglas and his sister; and I went to ask him about it, but I found it was all given up. I came back this afternoon, and I wish to tell you that I am sorry I went away. I ought not to have done it."

"Will you have the goodness to state where you slept last night?"

Mr. Desmond's tone was icy. His eyes never left her face.

"I went to Mrs. Toppings. She was very kind—she is Rawlings' sister—but he didn't know anything about it. I didn't do anything improper, grandfather, don't look at me so! I am sorry. I can say no more."

"But I can say a great deal more," said Mr. Desmond sternly, "I would have you remember what I said to you the other day. If you once leave this roof, you do not come back to it. I am not one to be trifled with in this manner. However, I am not going to waste words with you to-night. You can leave me. I will see you again on this matter."

Jean left him. Never had her grandfather spoken to her with such cold, hard determination in his tone. He had been passionately angry with her many times, but there was now a look upon his face that made the girl shiver.

"I believe," she said to herself, as she lay her tired head on her pillow that night, "that he hates me, as he hated my mother."

CHAPTER IV

A FRIEND IN NEED

"My friends have come to me unsought; the great God gave

them me."—Emerson.

THE expected interview did not come off. Jean saw her grandfather only at meal-times, and then he was coldly distant and polite to her. She wondered her escapade had been treated so leniently, and she began to look forward to Colonel Douglas's promised visit as the means of conciliating her grandfather. He arrived on a beautiful spring evening. Jean welcomed him in the garden, for her grandfather had not returned from his ride.

The Colonel looked at her radiant young face with interest.

"I am so glad to see you," she said, "from entirely selfish views. I am hoping great things from you. I was awake half last night, thinking about it. I don't know how you are going to succeed, but you must, you will, won't you? And I'll thank you all my life long, for the trouble you are taking."

"Ah," the Colonel responded with a humorous shake of the head. "It is a responsibility to push a young bird out of the nest. Experience may teach you to reproach me. I doubt, if I shall deserve much gratitude."

Jean looked up at him soberly and wistfully.

"I am grateful to you for making me come back. I acted on impulse. I have been thinking a lot, and I've come to the conclusion that a change of life means a great deal more than I thought it did. If this house were more of a home to me, I would never wish to leave it. If grandfather loved me, I would thankfully stay with him for the rest of my life."

Colonel Douglas was surprised at the depth of feeling in her tone.

"Sometimes we misunderstand those who love us best," he said. "It isn't always the ones who are most demonstrative, who are the most genuine."

Jean smiled rather bitterly.

"Ask grandfather if he has the least liking for me, and hear what he says. Oh, Colonel Douglas, I am so lonely, so friendless! I can't help telling you, but do you know, you are the first person who has taken the smallest interest in me, since I left school. It is so good of you. I don't think I shall mind it when I take up painting, but here I have nothing to do, nothing to read, and I think of myself all day long, until I sometimes wish there was no such person in the world as Jean Desmond!"

She broke into a little laugh, and turned to pick some daffodils in a bed close by.

"Ah, well," Colonel Douglas said cheerily, "when your circle widens, and you know a few more people, you will become so interested in some of them, that you will almost forget your own existence."

"Do you think I shall?" she asked, looking up at him quickly. "Ah, you are laughing at me! Come indoors, will you? I see grandfather riding round to the stables."

She was silent at dinner-time, leaving the conversation entirely to her grandfather and his guest. But as she left the room, Colonel Douglas met her pleading glance with a reassuring nod, and Jean wandered about the empty drawing-room in a fever of unrest and anxious conjecture.

She did not see the Colonel again that evening, and her dreams that night were disturbed by visions of a battle royal waging between him and her grandfather.

But after breakfast the next morning, Mr. Desmond summoned her to the library, where she found Colonel Douglas engrossed in some old parchments and her grandfather looking very grim and determined.

"I sent for you, Jean, as I have been hearing from Colonel Douglas that you have been making complaints to him of your life here!"

The Colonel raised his eyebrows, but did not look up from his parchments. Mr. Desmond continued—

"I have no wish to keep you here against your will. Your act the other day has quite removed the slightest desire on my part to have you here. I was angry at first at your wilful determination to do the one thing I have wished you never to do, but now it is quite immaterial to me. You have enabled me to snap the tie between us with the greatest ease. Still, as I say, I think it is fair to you to give you your choice. I had intended making you my heiress. You are the next of kin. If you like to stay with me, and act as a dutiful granddaughter should, I will overlook the past, and let my will stand as it is.

"If you are determined to follow your mother's profession, I will allow you £150 a year for the remainder of my lifetime, and you are at liberty to leave this house to-morrow. Only remember, whatever happens, you never enter it again. Henceforth, you will be a stranger to me. And after my death, you will have to depend entirely on your own exertions. For you will never receive a penny more from me. Colonel Douglas knows of a lady in London who is ready to receive you as a boarder. He will give you her address, if you wish to have it. I give you your choice; I am not accustomed to have friction in my house, and the sooner this matter is settled the better it will be for both of us."

There was silence. Jean's heart thumped loudly. Her liberty had come at last, and yet now that a crisis in her life had arrived, she shrank for a moment from the unknown future.

Colonel Douglas glanced at her. She looked such a child, as she stood facing her grandfather with her hands clasped behind her back, and her little head held so bravely up, that for a moment, he thought of dissuading her from the step he had made so easy for her to take.

Jean's lips quivered slightly.

"You don't want me to stay with you, grandfather?" she queried. "You will not miss me, if I go? If I thought you would care—I—I—"

She stopped.

Mr. Desmond's face was cold and impenetrable.

"My likes or dislikes are of no moment to you. They never have been. The choice rests with you."

Jean's eyes had been filling with tears. She passed her hand lightly across them, then spoke out clearly and decidedly without a trace of emotion in her voice.

"I will go, to-morrow if I can. Colonel Douglas will you tell me about this lady? Does she expect me?"

"I will have a talk with you later about it. Your grandfather and I are going to be busy over some manuscripts this morning."

The Colonel spoke gravely and quietly. Mr. Desmond opened the door and dismissed his granddaughter with cold courtesy. Jean fled into the kitchen garden, and paced the paths in an excited, troubled frame of mind.

"I have done it! I shall belong to no one in future, and I think he is delighted to get rid of me. Oh, I wish, I wish I had a mother living!"

Tears fell fast; then she dashed them away, and joined Rawlings, who was in a small forcing-house.

"Rawlings, I am going to be an artist! Grandfather is letting me go to London. I shall speak as I like, do as I like, and think as I like. Wish me joy! No more of this flat, dingy marshland? I shall work amongst beauty, and take my holidays in the most exquisite haunts of the world. I shall be an independent woman with money at my back. I must pinch myself hard to make sure I am not dreaming. And you will all go on here, year after year, and forget all about me. And then perhaps one day, you will hear of a wonderful picture gracing the walls of the Royal Academy and making everybody talk about it, and you will be told that Miss Jean Desmond is the celebrity who painted it, and then you will wonder how Miss Jean has been getting on, and if she remembers the talks she used to have in this old kitchen garden with you!"

Rawlings looked at his young mistress's bright flushed face, and shook his head with a knowing smile.

"Eh, Miss Jean, and perchance, you'll be sighin' for the good old times when you was young and careless, and had a comfortable home, and was sheltered and cared for, and yet didn't know it!"

"I'm like that crimson rambler," said Jean, pointing to the straggling creeper covering an old potting-shed, "Do you remember when you hammered and hammered, and pruned it and flattened it against the wall? It was always trying to burst away from you, and when you would be master, it at last gave up trying to have its own life, and dwindled and pined in reckless despair. You were angry with it then, and said you would leave it alone, and the poor thing lifted up its head, and found that life was worth living after all. It shook out its branches and flourished and rejoiced. It left the hateful wall with its nails and wires, and stretched out to the old shed, and now, it's a miracle of beauty and strength. Even you allow that some things flourish best with no restraint."

Rawlings eyed the rambler with disdain.

"Poor misguided thing!" he said. "I allow I did spend a mint o' time tryin' to make it into a decent shape and size, but I was expectin' great things from it. Yes, Miss Jean, it makes a great show of growth, and its blossoms are many and gaudy, but where is the scent and sweetness that belongs to the rose tribe?"

"Don't you go for to describe yourself as a crimson rambler, there be many of 'em in the world. They lives and flourishes in their own way, and are never checked and hindered. They makes a show, but never makes the atmosphere sweet around 'em. I wouldn't give tuppence for a rose without scent; 'tis an utter failure of its tribe. The rambler be a common hardy creeper to be sure, and 'tis not so out of place on a potting-shed, but we do look for better things from you, Miss Jean; and believe me, growin' as you like, anywheres and everywheres, you're certain to degenerate into a scentless plant!"

Jean never got the better of Rawlings in argument, but woman-like, she would not be crushed.

"Oh, well, there are other things besides sweetness in life, there's strength and sturdy goodness. I don't think I like very sweet people. There was a girl at school all gush and sentiment, and every one was always 'a dear' and 'a darling' to her. I longed to shake her sometimes! If I'm not a 'sweet' character, Rawlings, I can try to be a strong and a good one."

Then she added wistfully—

"Do tell me you're sorry to lose me, Rawlings! Will none of you care, I wonder! Grandfather is thankful to see the last of me; and remember, I am never to come back here, never! I have had my choice. I could have stayed on here always, if I had liked. I would have grown into a little old mummy of a woman; my meals would have been the excitement of the day; and I would have nodded in my chair for the rest of the time. Would you like a mistress like that, Rawlings? Thank goodness, that will not be my fate! Oh, say you're glad for me, and sorry for yourselves, that's what I want you to say."

"I'll say with truth, Miss Jean, that we shall miss you sorely, but I doubt if I can be glad for you."

Jean gave an impatient laugh, then danced away singing at the top of her voice—

"From life without freedom, oh who would not fly?

For one day of freedom, oh! Who would not die?"

Rawlings shook his head after her.

"From overmuch training to none at all, may the good Lord deliver her!"

After luncheon, Colonel Douglas asked Jean if she would come out for a walk with him. She gladly responded, and they started across the marsh together.

"I am so very grateful to you for making it so easy for me to go," Jean said earnestly. "I do not know how you have managed it, but grandfather is letting me go so much easier than I thought he would, and it is much nicer going with his consent than without."

"I wonder if you are quite aware of the consequences of this act," Colonel Douglas said, looking down upon her with kindly interest. "Do you realise that you are putting away a fortune from you? Your grandfather is a wealthy man, he tells me, though he lives in such simple style. You would inherit everything at his death. Will you live to regret the loss of this?"

"I am sure I shall not," Jean said decidedly.

"You see," she went on, with an old-fashioned air. "I have lived quite long enough to see that money doesn't make you happy; it only makes you comfortable. And to be comfortable means to be very dull, for you have no ups and downs to be exciting. It is all level monotony. I should get tired of it very soon. Of course, if I had a lot of money, and could do exactly as I liked, it would be very nice at first, but I know at school the rich girls were the most discontented. They had so few pleasures compared to the poor ones. A drive in a carriage was nothing to them; a bag of buns or a present of half a crown they turned up their noses at, and I believe it's just the same with men and women. I don't want dull comfort, I want exciting variety, a taste of going without, and a taste of having. I sha'n't be so very poor, you know, Colonel Douglas. £150 means boundless wealth to me."

"Now, tell me about this lady. Who is she, and what is her name, and where does she live? I know so few women. Will she be like a governess or a friend?"

"One question at a time; you quite overwhelm me! She is an old friend of my sister's and of mine. I hope she will become yours also. I have never known any one who does not like her. She lives in a small square leading out of Kensington High Street. Her name is Frances Lorraine."

"And is she old or young? You must excuse my questions, but it is a very important matter to me, as I am going to live with her. I have seen no women since I left school, except our two old servants, and I think I shall find them more difficult to get on with than men. I know I would always rather talk to Rawlings than to Mary or Elsie. Men aren't so fussy, and they're blunt and plain-spoken. The governesses as well as the girls at school were always making and having mysteries. They loved them. Now I hate anything I can't see and understand. Is Miss Lorraine a fussy, mysterious person?"

"I am not going to offer an opinion. You must see and judge for yourself. If I were young, I should like to be under her wing."

Jean looked up at him meditatively.

"I wish we could change places," she said with a sigh. "It must be so delightful to be a man, and to go where you like and do what you like, without any one questioning proprieties. Do you know that Mary and Elsie were both quite shocked that I went to see you in London? Now was it a very dreadful thing to do? Put yourself in my place. What would you have done?"

Colonel Douglas laughed aloud.

"Probably the same as you did, if I were give back my youth again, but at my present age and outlook, I don't think I should have left home at all."

"Ah, you don't know what it is to pant and long to do things that you are forbidden! Not wrong things; I don't think I want to do them; but painting is not a sin, and I cannot keep from it."

It was in this way they walked and talked, Jean doing most of the talking. As they neared the house again, Colonel Douglas said, "Will you take a bit or advice from one who has seen something of the world into which you are going?"

"Of course I will, gladly," was the eager response.

"Seek the best thing first, not last."

"That sounds vague. What is it?"

"The one thing that will bring no disillusion nor bitter disappointment. It must be the genuine thing, not a sham or counterfeit."

Jean raised a puzzled face to the speaker.

"What is it? Fame, I suppose? I am going to work for that."

The Colonel smiled.

"You have a lot to learn. Well, you will be in good hands. Frances Lorraine will be a safe counsellor."

He turned the conversation by asking her about her drawings, and once embarked on the present love of her life, Jean grew eloquent.

She came home in radiant spirits.

"Elsie," she said, as the maid came into her room with a message, "Colonel Douglas is the very nicest man I have ever seen. He is the only man I know that listens and doesn't talk!"

CHAPTER V

A NEW LIFE

"I am young, happy, and free.

I can devote myself: I have a life

To give."—Browning.

IT was five o'clock in the afternoon, and the end of April. A cab with luggage was threading its way along Knightsbridge. As it approached Kensington Gardens, and the fresh green of the trees formed a refreshing contrast to the rows of buildings just passed, an eager young face looked out.

It was Jean on her way to her new home, and she was in an excited frame of mind.

"Oh," she exclaimed, "I am glad London has no marshland! How I love trees! And how few I have seen in my life."

Then she laughed at her thought.

"To come to London to see trees! What would Londoners say?"

The cab moved on through the busy thoroughfares and then suddenly turned down a quiet side street. When it stopped, and Jean jumped out, she found herself in front of a small old-fashioned terrace facing a green square; balconies were outside the upper windows; it reminded her of seaside lodgings, and she gazed at her surroundings with eager interest.

The door was opened by a neat servantmaid, who took her through a dark hall, up a narrow staircase, and ushered her into a quaint drawing-room. But though the room was rich in foreign curiosities, old lacquered screens, and rare china, Jean's eyes were fixed on the centre of it all—an unpretentious, quiet little lady seated at her tea-table.

She rose, and came forward at once.

"I am very glad to see you. You will be glad of a cup of tea. Come and sit down."

Jean's face brightened. The words were not much, but the handclasp was firm and true, and the tone brightness itself.

Miss Lorraine carried with her everywhere the impression of sincerity and truth; her blue eyes sought her friends' faces with compelling persuasion and goodwill. They seemed to say, "I see through you and all your outside artificiality, and I like you."

The consequence was she was a general favourite. Her plain-spoken words were always accompanied with a humorous smile that made the truth palatable. A well-known hostess in society said of her once, "Frances Lorraine is a living wonder. She tells the truth to every one, and yet gives no offence. She is the only person in town that can do it."

When Jean was sipping her tea, her eyes found time to look round her. After the large stately rooms at her grandfather's this was a welcome change. It was essentially a living-room, the well-worn books lying about, the work-table, the business-like writing-desk, all testified to that fact; but the fragrant flowers and well-cared-for ferns, the choice pictures and numerous pretty knick-knacks, bespoke the owner's refinement and good taste. A rough-haired Irish terrier sat up with ears erect and eager eyes watching his mistress's every movement. Jean put down her hand and patted him.

"I'm so glad you have a dog," she said.

"You are fond of them? Doughty and I have lived together for many years. It is good to have a silent friend who receives confidences but never passes them on."

Jean pondered over this. Then she looked up and encountered Miss Lorraine's kind blue eyes.

Impulsively she put her cup down and exclaimed, "Oh, Miss Lorraine, I hope you will like me and help me. I am taking a step in the dark, and London is an unknown place to me. Colonel Douglas said you would advise me. Do begin at once. I am longing, bursting, to be at work!"

"We won't waste time, I assure you. London is the place for those who don't like waiting. Everything is rushed."

"You are laughing at me."

"No, I am not. In ten minutes, I can tell you all you want to know, and then you will like to go upstairs to your room, will you not? Now I conclude from what I have heard, that a School of Art is the best place for you at present. You have never received any lessons, have you?"

"Never."

"Pick out your best sketches, and to-morrow morning we will go and get the first interview over. If you are advanced enough to be put into the life model class, you will be told so at once. If you have to start from the bottom of the ladder, and be put with beginners, I suppose you will be equally willing."

"Yes," said Jean promptly. "I don't mind what I have to do. I shall love it all. Can I go to the Art School easily from here?"

"Quite easily. It is within a walk, if you are a good walker, and I would advise you for the good of your health to take as much exercise as possible. Doughty and I walk a great deal. Hansoms are expensive, omnibuses stuffy, and I would rather pay a shoemaker's bill than a doctor's any day!"

"Will attending a School of Art be expensive?" asked Jean. "How many years do you think it will be before I can start a studio of my own?"

Miss Lorraine shook her head and laughed.

"An old music master of mine used to be very fond of this saying: 'The top of the tree is not jumped at!' How long will your patience and perseverance last? Have you a good stock of those necessary and useful virtues?"

"I don't think I have a stock of anything," Jean replied, "except wishes, and I've crowds and crowds of them!"

"They are the handle to the saw. Now, shall we come upstairs? I don't think you will find this School of Art at all beyond your means."

Jean followed her hostess up to a cosy-looking room above the drawing-room. A good-sized table and easy chair were drawn up to one of the windows which overlooked the square.

"You will want to get away from me sometimes," said Miss Lorraine with a smile, "so I hope you will have space to read or write. I advise you to keep your painting entirely for your school."

Then resting her hand lightly on the girl's shoulder, she added with much feeling—

"My dear child, I mean to take the best care of you that I can without worrying you. Use me as you like. As a safety valve, if you are in need of one; as an 'Inquire Within' or directory or a modest encyclopedia. I am quite sure that we shall be happy together. Later on, you shall tell me as little or as much as you like about yourself. I am very interested in you."

Jean's eyes filled with sudden tears.

"I have never had any one take an interest in me," she said; "at least not since I left school. And do you know, it is only since I have grown-up, that I have begun to miss my mother."

Miss Lorraine stooped and kissed her and Jean laid her head on her pillow that night without a fear for the future, or a shadow of regret for the step she had taken.

The next few months were rosy ones to her. She plunged into her beloved art with an energy and dogged perseverance that astonished Miss Lorraine. She could talk of, and think of, nothing else. Art and artists were all the world to her. She read and studied when not employed with her brush, any books that she could get hold of, provided they bore the stamp and impress of Art. Other subjects did not interest her.

Miss Lorraine watched her with some amusement and a little concern.

"Don't live your life so fast," she would say to her. "You will get to the end of it too soon. Enlarge your borders."

And when Jean would wax indignant at the idea of her borders being confined and narrow, Miss Lorraine would shake her head wisely, but say no more.

Jean made many friends, and when not actually painting, visited a good many picture galleries and studios. When the hot months of summer came, she went into the country with a young couple to whom she was devoted, a Mr. and Mrs. Blake. They were both of them rising artists, and had taken a fancy to the impulsive, earnest-hearted girl. Miss Lorraine at first demurred, but when she had made inquiries amongst her numerous friends, and discovered that the Blakes were steady and quietly disposed, she gave her consent, and Jean came back to her in the autumn with roses in her cheeks and a light in her eyes which bore testimony to the good it had done her.

One afternoon, Colonel Douglas dropped in to tea. Jean was gazing dreamily out of the window, and did not notice his arrival.

She announced thoughtfully—

"I used to think that beautiful faces and figures have been the highest ideals in Art; but my eyes been opened this summer. I think nature itself without them is better."

"Hear! Hear!"

Jean turned hastily.

"Oh, Colonel Douglas, is it you? Do you agree?"

"Yes, I think I do. I see you have enjoyed your country jaunt."

"Oh, so much!"

Jean turned round from the window with an eager, glowing face—

"I have been down to Devonshire, Colonel Douglas. I have never seen such delicious haunts before. Every square inch of Devonshire ground seems rich in beauty. I suppose it is my home having been amongst the flat, monotonous marshes that makes the hills and dales in Devonshire such a delight. It has made me wonder why artists spend the greater part of the year in town."

"I think you will find that landscape painters are oftener out of town than in it. How is your painting getting on? Is it a success? Is life satisfying you?"

"Oh yes! Everything is perfect, except my own productions, but I am getting on, am I not?" She appealed to Miss Lorraine.

"Yes, your friends the Blakes told me you were considered to have real talent."

"And," said Jean, standing up and clasping her hands behind her, and addressing herself to the Colonel, "the next step is Paris!"

Colonel Douglas's amused look died away. His face fell. Then he glanced at Miss Lorraine, who was in the act of pouring him out a second cup of tea. She looked at him gravely in response.

"I have heard a good deal about Paris lately," she said.

The Colonel shook his head at Jean.

"Oh, you young people! Nothing satisfies you! You have not been in London a year yet, and now you want to leave it!"

"Not directly. I am going to work hard all this winter, but the Blakes are going to Paris next spring, and they want me to go with them. They are going to a studio there, and I can join them. I do hope you approve. I feel," here she laughed merrily, "that you are a kind of guardian to me."

"I do not approve of Paris," said the Colonel shortly.

"Oh, please do! I must go there. It is an education, and I can afford it. I have talked over ways and means with the Blakes. All artists drift off to Paris. I shall not take up my abode there. If Miss Lorraine is not tired of me, I shall return to her. But perhaps I shall have painted a picture by that time that will bring me money and fame."

She looked somewhat wistfully at the Colonel.

Though she saw him seldom she valued his good opinion, and she felt that her Paris scheme had been a distinct shock to him.

"I saw your grandfather yesterday," Colonel Douglas said.

"Did you?" Jean responded in an indifferent tone. She was disappointed that the Colonel purposely changed the subject.

"He was full of animation over a young cousin of his, the son of a man who died in Australia. He has invited him to take up his quarters with him, and told me he intended making him his heir."

"I am so glad," Jean said cheerfully. "I shall like to think that there will be some young life in that stagnant place. He is a man, so he will be able to come and go. And now I must say goodbye, Colonel Douglas, for I promised to go to see a friend of mine—an art student who is ill."

She left the room, and there was silence for a few minutes. Colonel Douglas put his empty cup down on the tea tray, then took up his favourite position on the hearthrug with his back to the fire. His keen eyes roved over the dainty old-fashioned room, and then at last rested on Miss Lorraine's face with an amused tenderness in their gaze. "Your duckling is about to take to the water," he said.

Miss Lorraine looked up at him with a smile. "Yes," she said. "I want your advice. What am I to do? I have not full control over her. She is so wilfully determined about this, that I have thought it wiser not to object. She is a dear warm-hearted child, but at present her whole heart and soul is in her art. And, of course, she is influenced by those with whom she is so much."

"Will they make a real artist of her?"

"Ah! That is the question. I have had a long talk with one of the masters who is interested in her. He says she has talent, perhaps genius; yet he does not think she will do anything great. But who would have the heart to say that to her? She is so buoyant and hopeful about the future, so perfectly happy with her taste of Bohemian life!"

"She must buy her experience," Colonel Douglas said. "You will have to let her go to Paris."

Then he gave a little sigh. "I want your advice, Frances. It always rests me to come here and have a chat with you. I told you about the widow of my old friend Thompson?"

"Yes," said Miss Lorraine brightly. "How is she getting on? You have helped her a good deal. Are her boys doing well?"

"Yes. Alf is getting on in old Grand's office; and the younger, Bob, is articled to a lawyer. It is their mother whom I am anxious about. She is not strong, and has not the means to buy the nourishing food she needs. I have been in the habit of taking her down little trifles now and then, and sometimes sending a small hamper to her, but—"

He hesitated and a dull flush mounted to his cheek. "Certain uncharitable people have been annoying her by foolish remarks, and she has begged me to visit her less frequently and send her nothing more. I wondered if I could still befriend her through you."