My Heart's in the Highlands

Amy Le Feuvre

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

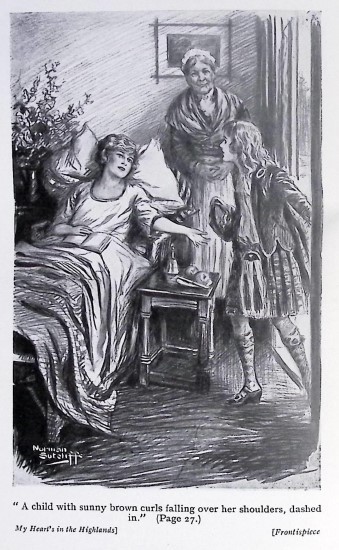

A child with sunny brown curls falling over

her shoulders dashed in. Frontispiece.

MY HEART'S IN

THE HIGHLANDS

BY

AMY LE FEUVRE

WARD, LOCK & CO., LIMITED

LONDON AND MELBOURNE

MADE IN ENGLAND

Printed in Great Britain by

L. T. A. ROBINSON LIMITED, THE BOTOLPH PRINTING WORKS

LONDON.

CONTENTS

CHAP.

BOOK I

I. A DOCTOR'S VERDICT

II. ALONE

III. MYSIE MACDONALD

IV. THE BIRTHDAY GIFT

V. FRIENDLY TALKS

VI. MISS FALCONER

VII. COMPELLED TO THINK

VIII. THE LAIRD'S AWAKENING

IX. DEPARTURE

BOOK II

I. AT THE GREEN COTTAGE

II. A NEW FRIEND

III. CHASING SHADOWS

IV. AN OLD FRIEND

V. A SATISFACTORY INTERVIEW

VI. THE LAIRD SPEAKS

VII. AN ACCIDENT

VIII. AN ALTERED OUTLOOK

BOOK III

I. HIS BRIDE

II. SOME GUESTS

III. HECTOR ROSS

IV. WINTER IN THE GLEN

V. ROWENA'S POWER

MY HEART'S IN THE

HIGHLANDS

BOOK I

CHAPTER I

A DOCTOR'S VERDICT

"We know

That we have power over ourselves to do

And suffer: What—we know not till we try."

Shelley.

"I DO wish you would be serious!"

"Why on earth should I be?"

Rowena Arbuthnot leant her elbows on the wide windowsill and looked in upon her sister-in-law from the garden, with her mischievous blue-grey eyes which always seemed to twinkle with some hidden joke. Rowena's eyes had been the cause of her continually getting into trouble, from the time she had been a child, when the rector of the parish had requested her not to laugh at him in the pulpit.

She was older now; and had gone through more trouble than most girls of her age. But though her lips were grave, and a trifle sad when in repose, yet her eyes had never lost their gleam of hidden laughter.

Young Mrs. Arbuthnot, sitting in her pretty drawing-room, stitching away at a white frock for her youngest child, felt impatient with Rowena.

"I never shall understand you," she said; "I thought you and Ted were so devoted, that if you had not cared a button about the children or me, you would be disappointed at not coming with us. Our home has been yours for the last four years; and we have always looked upon you as one of the family."

"My dear Geraldine, tears are too expensive a luxury to be wasted in public. Shall I conjure up two for your benefit? I might if I tried hard."

"I hate you when you are facetious!"

"I won't be. Let us talk wisely and soberly. Is it my fault that Ted was cheated in the horse deal, that I mounted a half-broken vixen, and was pitched out of the saddle on the very hardest bit of ground going? Is it my fault that that dear old Niddy-Noddy should insist upon my lying low for a year? I don't want to be an invalid for life. It isn't an attractive prospect. And you wouldn't like a bedridden crock to be attached to you for evermore. Isn't it worthwhile to escape that fate if I can? To forgo my journey to the East with you is, of course, a trial. But what am I, if I can't take my share of disappointments philosophically?"

"Yes, yes, I know you've got an inexhaustible fund of philosophy and patience; but where are you going, what are you going to do? If only Ted had not let the house! But we're so hard up—and—really, Rowena, you ought to be lying down at this moment! What is the good of only following half Dr. North's advice?"

Rowena held up a bunch of dew-sparkling roses.

"My dear, I'm coming in—but I must have these to refresh me." She slipped in over the low window, and went to a couch in the farthest corner of the room. For a moment or two she occupied herself in putting her roses into a bowl of water by the side of the couch; then quietly laid herself down among the cushions with a little sigh—or was it a long-drawn breath of pain?

"Now talk away, Geraldine! I'm chained here till luncheon, and you can say all you have in your mind, but we won't grumble over what cannot be helped."

"Well, have you any idea what is to become of you?"

"Not the slightest. You see Niddy-Noddy only sprang my fate upon me yesterday, and you are the only one who has seen Ted. I was in bed when he returned last night, and he was off to town before I got up this morning."

"He has so many arrangements to make before we sail. And Ted is no good for practical common sense. If you only had money of your own, how easy it would make things!"

It was not often Geraldine Arbuthnot alluded to Rowena's penniless condition; and the girl laughed to hide the hurt of it.

"Yes—and a crippled beggar is worse off than a healthy spry one. I allow I am in an evil case! It's a pity you and Ted set your faces against the job offered me."

"Ted has some pride," said Mrs. Arbuthnot with raised head. "It isn't likely he would let his sister be a paid clerk to that bounder Tom Corbett! And I wanted you badly. Goodness knows what I shall do without you now. You weathered me through my bad time three times over, and I shall never forget it. The chicks will be lost without you—and I was quite counting on you to keep them happy on board ship!"

"Oh, yes, you'll miss me," said Rowena with honest conviction. "What craft can I do on my back, I wonder? Not basket-making! I could make rugs—those Eastern ones—I really think that is an idea! But who would buy them? Would that hurt Ted's pride, if I wrote a round robin—to our friends, asking for their support? How would it run? After this style:"

"'An invalid much in want of the necessities of life, is starting rug-making. Orders received and promptly executed. Designs straight from India and Persia; and colours to blend with purchaser's rooms.'"

"Oh, do be quiet, Rowena. Don't talk such nonsense. Here are the chicks. Nurse, bring them in here."

Mrs. Arbuthnot leant out of the window as she spoke, and a moment after, two little fair-haired boys burst open the door, their baby sister struggling in her nurse's arms to follow them.

"Where's Aunt Rony?"

"Here, Buttons, here; in my little corner!"

Buttons flung himself upon the couch.

"Are you playing a game? Are you in bed?"

For the next few minutes the children's chatter filled the room, but the nurse soon took them off; Buttons and his twin Bertie beseeching their aunt to come up to the nursery and have a game with them after tea.

When they were gone there was silence for some minutes; then Mrs. Arbuthnot folded up her work.

"Well, Rowena, we seem to come to no conclusion. Ted told me to talk it over with you."

"But we have. Ted must lend me a little money—and I'll move into rooms somewhere, and teach myself a craft and pay him back as soon as I can. And then at the end of the year, if I'm cured, I can come out to you if you want me."

"I shall always want you. You do too much for me. I shall never be content to live without you. Well, I must go and write some letters. I'll send Ted to you directly he comes home."

Rowena's bright eyes closed when her sister-in-law left the room. The pain in her back was acute now, and she was glad to rest. Her doctor had told her that there was a slight injury to her spine, and that she must lie on her back for a year, if she wished to be strong again. She had never remembered a day's illness in her life. She rode, she boated, she hunted, and she fished, always in company with her beloved brother. His marriage had not lessened the bond between them, for his wife was devoted to her, and had not a particle of jealousy in her composition. She did encroach on Rowena's good nature, but was conscious of it herself, and told her husband that Rowena was but an unpaid servant in their house.

"She is a companion to me; nurse and governess to the boys; housekeeper and general adviser; and comforter all round. She really deserves double the allowance you give her."

But Ted shook his head.

"She's my sister and chum—I couldn't expect her to take money for her services."

Now he had been summoned to India to join the foreign battalion of his regiment, and Rowena, owing to her unfortunate accident, was to be left behind.

She felt it keenly; she loved the pretty home which lay amongst the Surrey Hills; but would have accompanied her brother cheerfully all over the world. Several times she might have married, but so far, no man had eclipsed Ted's image in her heart. She always compared her lovers with her brother, and always found they lacked his personal attractive qualities.

He came in at five o'clock that June afternoon, and found his way to her almost immediately.

"Rowena, this is bad news."

"Didn't you expect it? I did. I knew from the minute I was carried away from my spill that there would be no India for me."

"But we'll rig you up a bed on board; and in India you can lounge and laze to your heart's content. Old North doesn't know what he is talking about."

"It's no go, my dear boy, you'll be on the move in India yourself, you told me so. I will not be a useless encumbrance to you. No. I'll do the thing in style, and be a bed-lier till I'm cured. I mean to be cured, Ted; and a year will soon slip by. It isn't only Niddy-Noddy who has settled up my fate. That London specialist gave the same verdict."

"But where are you to live?"

"In my skin. Don't ruck up your forehead like a wizened monkey! I've been calculating that I shall require no clothing for a year, and no footgear. I'm very rough on my boots. So my allowance will go for my food. I must get cheap lodgings somewhere. One room will do for me, as I shall always be in bed. Why, lots of old bedridden women in the country villages live on less than you give me for my clothes."

Her brother paced the room restlessly. Then his face lighted up.

"How would you like to go up to that Scotch shooting lodge of mine? Could you stand the quiet and solitariness of it? There's old Granny Mactavish who would wait upon you. And then there would be no rent to pay, and she keeps a cow and some hens, so those would feed you."

Rowena's eyes literally danced in her head.

"And Geraldine says that you are not practical! Ah, here she is. Come along and see how quickly we've settled things. I'm going up to Loch Tarlie. And a cow and some hens are going to nourish and sustain me!"

"Oh, Rowena! Ted, you will never encourage her to go there! She could die and be buried before we should hear of it, or anyone else. Besides, I don't think it would be proper. Isn't she too young to live in the wilds by herself?"

Both Ted and Rowena began to laugh, and Rowena's laughter was so infectious that Geraldine's grave face relaxed.

"Is it a joke?" she asked. "Of course you might like it for the summer, Rowena dear, but think of the winter! How could you live there? And you're a sociable creature and have always been accustomed to see a good many people. Why, it is fifty miles from rail! And there are no shops, or libraries, or theatres, or concerts, or the mildest form of amusement for you!"

Rowena held up her ten fingers.

"And now let us count the advantages:"

"No temptation to attract one off one's couch. A never-ending

panorama of colour and light and beautiful scenery before

one's eyes. No rent to pay."

"No servants to employ."

"A home of one's own—I have known Loch Tarlie since I was six—

milk and butter and chickens all to hand. Ted asserts I want

nothing else."

"No newspapers, to make one realize that England is going,

or has gone, to the dogs."

"And life-giving, intoxicating moor air to make one feel glad

every day of one's life that one is alive!"

"Yes, Geraldine, I am going and will stick it out for the winter there. Old Granny Mactavish is as spry and active as a girl. If she can stand the winter, why shouldn't I? And oh, do you think old Niddy-Noddy would let me transfer my mattress to a boat? Think of my lying on a silver loch watching the trout and salmon leap and flash by! Perhaps with Granny's nephew, Colin, by my side, we could fish between us. Ted, is your mouth watering? And will you write by this evening's post and tell Granny I will have my bed made up in the green drawing-room, with windows down to the floor? I shall feel out-of-doors at once."

"You will want books," said Ted gravely. "I'll order a box from Mudie's to go down with you, and I say, Rowena, there's a first-rate travel book by a chap I knew in the war. He's a humorous sort of fellow, with keen powers of observation. It's about the Frontier up in Afghanistan. You must read it. I was dipping into it to-day at the club, and Murchison, who was reading it, said—"

"Ted, get off books this instant," said Geraldine, "and let us discuss the question of Loch Tarlie. How will Rowena get up there, and who will go with her? And she cannot live alone with old Granny Mactavish. We have always taken our own maids up there and a chauffeur. Rowena must have a nice maid to attend upon her."

"No, thanks—not if I know it! I couldn't stand the whines of a lonely frightened maid. No young person could stand a Loch Tarlie winter. As for me, I am as old as the hills. They say a woman is as old as she feels—and I feel just a thousand and one since my spill!"

"Oh, if you've made up your mind, any objection of mine will be waste of words. I wonder if the Frasers will be there this year?"

"Macdonald has taken possession of Glen Tarlie," said Ted; "but I don't believe he is there much. It's a pity his wife died—she was just Rowena's sort."

"You mean in the way of books," said Geraldine. "Well, I never liked her, she was so indifferent to him; and I think it was sheer wickedness to leave her baby to those Highland folks at the Farm, because she wouldn't be bothered with a child in town."

"I'm not going to see a soul," said Rowena in her cheerful voice; "so don't try to rake out company for me. Ted, write; there's a dear! I'm quite impatient to have it settled up. And as for the journey, Geraldine, I shall have a sleeper, and get on by myself. The guards are always attentive to invalids."

"That you shall not! I shall send Ellen with you. She won't come to India with me, and her home is somewhere in the North."

And so it was settled, and in about three weeks' time Ted with his wife and children were steaming down the Channel on a P. & O. boat, and Rowena was travelling up to Scotland with Geraldine's maid.

Rowena had kept a bright face to the last. But now she lay in her berth with closed eyes, feeling the chubby soft faces of her little nephews pressed against her cheek, seeing the wistful look in her brother's eyes and the tears in his wife's, and wondering if she would ever see them all again. And then she took herself to task in her usual style.

"This won't do at all! You've been shamefully spoilt these last four years—every one wanting you and making much of you. Those fat years have gone and now comes a lean one. Too much fat makes the liver sluggish. And you lived alone for two years with your poor fretful father, when he never wanted you near him, and wouldn't let you go away from him. Now you are going to live by your lone self, with no one to fret you; and if you can't employ yourself and enjoy yourself as well, I'm sorry for you!"

The journey to Scotland was made in driving wind and rain, but though Rowena felt the continual vibration of the train in every joint of her injured spine, she was as cheerful as a cricket, and kept Ellen in constant smiles.

"I never did hear a grown-up person talk such nonsense in all my life," she confided to the friendly guard, who took Rowena under his fatherly protection; "but she'd win a smile out of a cow, she would!"

Half a day's journey from Glasgow brought them to the last stage of their travels. Ellen was to take Rowena to the Lodge and sleep the night there. The little steamer was waiting to take them up the loch. Rowena insisted upon walking on to it, though she was forced to lean heavily on Ellen's arm. The rain had ceased, and the sun now shone out as it only does in the Highlands, illuminating every mountain height, with soft dreamy radiance.

"Ah!" said Rowena, subsiding into a lounge chair upon the deck; "now don't you wish yourself in my shoes, Ellen? And I am not to be torn away from it just when I am taking root, which has always been my fate before—I am going to sink into it and rest in it for three hundred and sixty-five days."

"I'm sure, ma'am, I only hope you will have some amusements to beguile the days," said Ellen.

She was looking round her with apprehensive eyes. The still silent waters of the loch through which they glided with its walls of green on either side, and the blue ranges of mountain that guarded it upon the horizon, seemed to her a type of prison.

Rowena now pointed out a beautiful glen across the loch.

A stack of chimneys rose up behind some trees.

"That's where we're going," she said.

Ellen gave a gentle sigh.

"It seems the end of the world," she said, and Rowena's low mellow laugh rang out.

"You'll be in dear noisy Glasgow again to-morrow, Ellen. Cheer up!"

The steamer put in at the small pier at the foot of the glen. There was a grey-bearded Highlander standing very straight and still upon the pier. Rowena greeted him with a radiant smile. Duncan Cameron had helped her many a time to stalk a stag. He had also been with her when she had caught her first salmon many years ago. He was her brother's head keeper, and had been in his employ for over twenty years.

"Granny was sayin' that you would be wantin' a hand up," he said. "Is it ill ye are, Miss Rowena?"

"I'm an infirm old woman, Duncan—jumped into my dotage in one black day! Why, what is that you've got there?"

"'Tis a cheer, miss—a cheer which the Ker-enel ordered to be brought for ye, an' tis I will be pushin' it up the wee bit brae!"

"Magnificent!" said Rowena, looking at the spick and span invalid's chair with its soft blue cushions: a lump gathering in her throat at this proof of her brother's loving forethought.

Helped into it by Ellen, she relapsed into silence, but she was gazing up the glen with shining eyes. The soft air, the afternoon sun, gilding the raindrops on the pines and birches, the sweet scents of the moistened earth underfoot, all soothed and rested her tired spirit.

Along the winding carriage road they went, under an avenue of ashes and birches; by the side of them a wide trout stream came dashing down from the heights above, finding its way into the Loch. And then they turned the corner, and on a flat plateau of green smooth turf, fringed with pines, lay the house. It was a low, long grey building, with windows opening out upon the lawn, and creeping roses covering an old rustic porch, which led into the hall. Inside the pitch-pine floors were covered with green druggetting. Old Mrs. Mactavish stood curtsying in the doorway. Rowena took both her wrinkled hands in hers affectionately.

"Here I am and here I shall be till you are sick of the sight of me!"

"Ach now, ma'am, with your jokes! Wae's me if ye will be stretched on your back a' the days o' sunshine, but I've done as weel as I know how to mak ye comfortable!"

She led the way into the room which Rowena had chosen for herself.

It was a long, low room with three beautiful windows reaching the whole length of the wall; the loch stretched out below the lawn; and there was a gap in the trees so that the view of the shining water and the wooded heights on the farther side lay open to the eyes. The floor was covered with the same simple green druggetting. Geraldine had good taste, and simplicity reigned all over the house. The walls were painted cream and the furniture was fumed oak, but the couches and chairs were all covered with green and white chintz, and Rowena's couch was drawn up near one of the windows, a table by its side. A bright wood fire was blazing in the low grate. The room looked cheerful; old Granny had even gathered some yellow flags and put them in a china jug upon the mantelpiece. There was a door leading into a similar room behind, originally the smoking-room, and now to be used by Rowena as her bedroom.

Ellen looked round with critical eyes, but even she could not find any faults with the arrangements for the invalid's comfort.

"And there's my granddaughter, Janet, will be up in the morning early," said Granny. "The mistress said she should wait on ye in the morn, and also in the eve."

She introduced a rosy smiling girl to Rowena, and Ellen heaved a sigh of relief.

"I'm glad you'll have somebody to wait on you, ma'am, for that old body seems ready for the grave!"

"Oh, Ellen, for shame! It is the outdoor work she does that makes her so wrinkled. Granny is good for twenty years yet. And you should taste her oatcakes and scones! No one can beat her at cakes!"

Half an hour later Rowena was lying on her couch with the table drawn up by the side of it; and even Ellen could find no fault with the creamy scones and oatcakes, the excellent tea and bowl of rich yellow cream, and home-made butter, which Janet smilingly brought to them.

Rowena went early to bed, and when Ellen left her the next morning she was unwillingly convinced that her charge would be comfortable, but "desperately solitary" she assured herself with a lugubrious shake of her head.

CHAPTER II

ALONE

"When from our better selves we have too long

Been parted by the hurrying world, and droop

Sick of its business, of its pleasures tired—

How gracious, how benign is solitude!"

Wordsworth.

"MY DEAREST GERALDINE,—"

"My thoughts have been with you, of course. At first I felt that my better half had gone with you, and only my feeble carcass left here, but you know my adaptability! In a coster's cart or Rolls-Royce car, a slum garret, or Park Lane mansion, I should be bound to get some fun out of it! And I'm not only getting fun but really steeping myself neck-deep with thrills of delight in my delicious atmosphere and surroundings! And you'll be glad to hear that I am growing into my bed, spreading my roots there, and almost getting to like an invalid's life! Well, what can I tell you? I begin my day with hearing pretty Janet's view of life. She's almost as talkative as her Granny, but has got very modern cravings! I end the day by a crack with Granny, who is anything but modern; and my interim is spent with many pleasant companions. A robin and a gull visit me daily—they bring others of their acquaintance who regard me somewhat indifferently and don't come again. But my robin never misses a day; and my gull walks boldly inside my room and up to my couch, where he expects, of course, some special tit-bits in reward for his friendliness."

"Duncan brings me fish, and talks over the prospects of the shooting. He does not like the man who has taken it."

"'He be ane o' these Englanders who fancies a kilt and a bonnet will turn him into a highlander—an' he be in an awfu' funk lest he miss his shot; an' spends muckle bawbees in endeavourin' to win approval!'"

"It appears he was one of the house-party at the Frasers' last year, and Duncan heard 'accounts' of him!"

"Granny's nephew, Colin, cuts our wood, runs errands, and is a first-rate gardener. The lawn is beautiful: the birds make it their playground. And now I must tell you that yesterday Duncan presented me with the sweetest Highland pup that you have ever seen! His name is Shags, a dog of good pedigree and one that will be a real companion. The collies live out-of-doors—they cannot be enticed into my room. Shags has established himself at once at the foot of my couch, and he understands my talk, and appreciates it. He has a very rough little head, and cocky ears, and bright brown eyes that wink in an understanding manner. His tail is always wagging, and life to him at present is one huge joke. He knows the power of his sharp little teeth, and uses them on everything in his way; but he is learning self-control and discretion, and I make him a fresh ball of rags every day, which he tears to pieces with relish and scatters to the winds. Tell the boys about him. He is quite a personality!"

"Tell Ted I'm steadily getting through the box of books; but I am doing a 'power of meditation' as Duncan says. And when I've nothing to do but dream, I dream with a vengeance. I am fed well, I sleep well, and barring the first two days, I have not had much grinding in my old back."

"Enough of me and my doings! Tell me all about yourselves—how the chicks like India—what they do and say. Have you a nice ayah? What is your house like? Who are your neighbours? Does Ted like his fellow-officers? I expect sheets and sheets from you. Don't you dare to forget the poor isolated prisoner of Loch Tarlie!"

"Oh, Geraldine, why aren't you all here with me! Then we should be happy indeed. Best love and hugs to the darlings."

"Your loving"

"ROWENA."

Rowena had settled down, as she wrote, into a quiet invalid's life. She had severe internal conflicts at first. She wanted so much to be up half the day at least. But a letter from her old fatherly doctor sent her to her couch, and kept her chained there. She was assured it was the only chance for her cure.

The first fortnight was fine. A sense of rest and peace stole into her heart as she gazed over the beautiful landscape out of her window. No two days were alike. The softness of the colouring of the distant hills, the shadows which ceaselessly flitted across them and the loch, and the fresh opening of the spring flowers in the garden, were a continual surprise and interest to her. She got Janet to bring her bowls of pale primroses and daffodils, and her room soon became a bower of sweet-smelling flowers.

Then, suddenly, the weather changed. There was a spell of wet and wind.

Windows had to be shut; the wind howled down the chimneys, and soughed through the trees, and tore some delicate young plants in the flower-beds to pieces, scattering the fragments over the lawn. The loch churned itself into a grey muddy froth, the singing birds fled to their nests and stayed there.

Rowena looked out of her windows, and for three days watched the career of the storm with the greatest concern. It really seemed at times as if everything young and fresh would be swept away.

After a time the wind fell, but the rain continued, and then it began to pall upon her. Would it ever be fine again? Would the hills ever appear out of their thick well of mist? She read till her eyes ached. She worked at her rug till her fingers ached. She meditated till her head ached. She yawned, she fidgeted, and finally she came to the conclusion that she was becoming unutterably bored.

Shags was restless and was unaccustomed to the closed windows. Hitherto he had wandered in and out of his own free will, and he basely deserted Rowena for the kitchen. Depression settled down upon her on the fifth day of storm and rain. After she had had her lunch, she began to wonder how she could get through the winter, if a wet week in June affected her so sorely. Shags' appearance for a time distracted her, but after a little he left her, and lay against the window, his nose close to the glass, showing in every hair on his head how much he disliked the indoor life. Rowena took up a fresh book and tried to forget herself in it; but the rain and wind began to get upon her nerves. Her book did not interest her—she tossed it aside.

"And in India they are revelling in sunshine! Perhaps Ted will be playing polo, or he and Geraldine riding out together. Oh, it's hard lines I shouldn't be with them! I shall forget how to talk, if I am shut up here much longer. I might as well be doing my time in a Dartmoor prison, or at Broadmoor."

Then she started—sounds came to her of a car of some sort coming up the drive. Could it possibly be a visitor? Hardly—on a day like this. She was not long left in doubt. Granny appeared at the door, with signs of agitation.

"If ye please, mem, may we shelter two bodies who be fair drowned in this awfu' rain? I cam' right awa to ask ye—for wi' one o' the family here it is no' to be expected I should do otherwise! 'Tis a mon an' a woman, but they be fair shrouded in their waterproofs and oilskins, an' I've not had a peep at them yet. Ye'll no' need to see them, for the kitchen is good enow for the like o' any traveller be they who they may! An' they do but want a dry an' maybe a cup o' tea! They be quite respectable folk I reckon. I may bid them welcome in your name?"

"Certainly, Granny, and if the lady would like to come in and see me, I shall be delighted, whoever she may be—a Glasgow shop-girl or a duchess! I would welcome anybody on an afternoon like this!"

"Aye, mem, we get mony sich days in our year-r!"

"Of course we do, but I'm not accustomed to them yet; and I've read till my eyes ache."

A few minutes later Granny ushered in a little old lady in a close dove-coloured motor bonnet. Her face was round and soft as a child's.

"How very kind of you to give us such shelter," she began; "and, oh!—if I may say it—what a charming room!"

"Now you've won my heart," said Rowena, holding out her hand. "Come and sit down, won't you, and talk to me. I am a prisoner, but I do agree with you that I have nothing to complain of in my prison. How does it happen that you are out on such an awful day?"

"It's my son, Robert; he has only just taken possession of his manse, and I've come to look after him. He had to see a sick man on this side of the loch, and so I wanted to see the country and he has motored me round."

"Is he the minister of Abertarlie? Granny Mactavish told me a new one was coming there."

"Yes, and from our snug little nest we look across at you; but we had no idea that any of the family were here."

"You are not Scotch yourself?"

"I am very Scotch by name—we are one of the Macintoshes, but you are right, I am an Englishwoman by birth."

"And so am I," said Rowena, smiling; "I have Scotch blood in my veins, and when I am in Scotland, I am Scotch. The English are a poor lot, you know! My brother only rents this lodge from General Macdonald. Do you know him?"

"My son has met him, but his house lies empty; he is hardly ever here."

"Won't your son come in and see me? I am one of his parishioners, you know. And we will have tea together presently. It will be my first party. Are your feet dry? Won't you change your shoes?"

Mrs. Macintosh held out two very pretty slender feet.

"I have been in the car the whole time. But as we got nearer your house, the rain came down like a waterspout. I will go and fetch my son. It is very kind of you to offer us such hospitality."

Robert Macintosh very soon appeared, a tall fine-looking young man with rather a stern face; but it softened as Rowena welcomed him with her happy smiling eyes.

It was a very successful little tea-party. Rowena had not seen many Scotch ministers, and those she had met were of a different stamp to Robert Macintosh. He was a gentleman, and his mother was a charming old lady with plenty to say for herself. Rowena explained herself very briefly.

"I am doing a kind of rest cure here—hurt my back out hunting and am obliged to lie on it for a time. My brother is abroad, so we shall have no shooting parties this year. I think he has sub-let the shooting to some fellow-officer of his; but not the house."

"You have books," said the young man, glancing at the low bookcase by the side of the couch.

"Yes, they are delightful company, are they not? Are you a reader? But of course you are? It is your avocation."

"Is it?" smiled Robert. "My mother would say it makes me a very unsociable creature to live with."

"It is irritating when one wants a cheerful gossip with him, to see his shoulders hunched up and his nose glued to a book," said Mrs. Macintosh quickly. "He is one of those readers who get so absorbed, that nothing but a shake and a scream will bring him back to me."

"Ah," said Rowena, "I plead guilty there. It is all right for oneself to be oblivious to all around, but a great bore to one's friends."

Then she and the young minister began talking of some new books; and the old lady sat and listened to them with great content. Janet soon appeared with the tea, and before it was over the rain had stopped, and the loch was shining like silver with the far-away rays of the sun.

When eventually the visitors left, Rowena was her bright cheery self again. But she took herself to task for her changes of mood, when she and Shags were alone together.

"Shags, you show your mistress an example of cheerful equanimity of soul! You are just as ready to wag your tail when the day is sodden and dreary as when the sun shines out; and as it will be my fate to be here through the very darkest, wettest months in the year, I am a poor wisp of a creature to be beaten down by one rainy week in June. It must not and shall not happen again, Shags! My universe does not begin and end with succulent luxury. Oh, Shags, you villain! I know what you're asking me! We'll have the window open, and then you will be free to gambol outside."

She rang the bell. Shags was waiting by the window expectantly, and when Janet opened the glass doors out he bounded. The air was sweet and fresh; the scent of a sweetbrier bush outside made Rowena's pulses beat with joy. She gazed out upon her green lawn. Shags went round it, sniffing at an old-fashioned flower-border. He unearthed a snail, turned it over with his nose in disgust, then made for a pert tom-tit strutting up and down the gravel path. The tom-tit flew away derisively, and Shags next examined with great interest a long tuft of grass. A frog leaped out. It was the first one he had seen, and he backed away from it in fright. Rowena watched him. Then the light on the opposite hills brought a gleam of delight to her eyes. It was so alluring, so exquisite, so varied in its movement and colour!

Granny came in later to inquire how she was getting on.

"Feeding my soul, Granny."

"Your soul wants bonnier feedin' than a' that." Granny was deeply religious. Rowena was not.

"Now you are not to make me discontented! I have a soul that wants beauty, and that will not be satisfied without it."

"I reckon there be mair beauty in the Creator than in His works."

"Granny, how do you like the new minister? Have you heard him preach?"

"Oh, aye—I went to kirk this Sabbath back."

"And does he preach well?"

"He does that, mem. His heart leapeth into his e'en wi' earnestness o' purpose an' persuasion. Eh, if ye cud get across in the wee boatie!"

"I can't, Granny. He will have to come and preach to me. He's a remarkably good-looking boy. I should like to see his heart leaping. Didn't you know he was the minister when you first asked me to give him shelter?"

"Deed an' no, mem, for 'twas in oilskins he were an' his mither was so spry in rinnin' ower to the hoos, that I fair speired she were just a lassie."

"I like them both. I told them to come over again soon."

"'Twill be mair company ye'll be gettin' nex' month," said Grannie comfortingly. "The lodges will be fillin' oop, an' Sir Robert Fraser be openin' his hoos nex' Tuesday!"

"It isn't company I want," said Rowena, smiling; "only the sun. I suppose the Highlands can't have all the good things in this world. There are few parts like it for beauty and romance, but I'm ashamed of my discontent, Granny! And just as I have learnt to be happy on my back, so I shall learn to be happy through the worst of weather. One can adapt oneself to anything! Habit is the main thing. The habit of content shall be mine."

The weather cleared the next day, but it was not settled. One afternoon, about two days later, after a couple of hours lovely sunshine, a sudden squall came on. The clouds were broken and the play of light and shadow on the opposite hills so fascinated Rowena that she took up a telescope which Duncan had brought her, and began studying the horizon.

Suddenly she made an exclamation and rang a bell by her side.

When Granny appeared she said sharply:

"Is Colin near at hand?"

"He has bin killin' a fowl, mem."

"Tell him to get the boat quickly. Do you see some one on the loch in distress? It looks like a small boy. Oh, don't stop to look, Granny! Colin will have younger eyes than yours—call him quickly. It is half-way across here, from the island."

Granny disappeared. Rowena listened impatiently to the voices outside her window. The loch was lashing itself into a fury. The small boat she had discovered with her telescope was now plainly discernible. But it was making no progress, only tossing up and down, a sport of the rough element around it.

It seemed a long time before Colin had started the boat, but Rowena saw it leave the small landing-stage at last and, to her great relief, two men were in it. Duncan had evidently appeared on the scene and offered his services.

Rowena took up her telescope again. She saw a little figure in bonnet and kilt sitting in the boat struggling very ineffectually with the oars.

"How like a boy," she thought, "to venture out on a day like this!" And then she saw from the efforts of the two rescuers what a strong wind and current was against them. Once a wave seemed to dash over the distant boat. Rowena held her breath, and then a call from Duncan—evidently an attempt to hearten up the little rower by telling him help was at hand. Slowly but surely the boats came nearer. At last they touched. Through the telescope Rowena watched the child clambering in from one boat to the other, then saw the men row back to the shore towing the other boat after them. Before they landed, Granny appeared in some excitement.

"It's that weeld bairn o' the laird's, an' near anow was she to her death, to be sure! Shame on Angus for lettin' the bairn tak' a boat this day!"

"What child do you mean? Boys will be boys."

"But she's a girl!"

Rowena looked up surprised.

"Who is it?" she asked.

"'Tis Mysie Macdonald, an' I'll be changin' her things surely! It's just a maircy o' the A'mighty's that the wee bairn is not drooned."

In a few minutes Rowena heard the sound of the men's voices and a clear treble between them. Then suddenly her window, which was half shut, swung open, and a child with sunny brown curls falling over her shoulders, dashed in.

"Granny Mactavish, I've come to tea with you!"

She stopped short at the sight of Rowena on her couch.

She was in a kilt which was wringing wet and dripped on the ground as she moved. But she held herself squarely and proudly, then doffed her bonnet like a boy.

"I didn't know there was anybody here."

"Come and speak to me," said Rowena, with her sunshiny smile. "I am not an old lady, only a prisoner."

The child looked up at her with bright interested eyes. "Who put you in prison?"

"An old man I call Niddy-Noddy."

"Oh, what a lovely name! Tell me about him. What's he like?"

"He speaks like this—"

Rowena drew in her lips till her mouth looked as if she had no teeth—she lowered her brows fiercely, and then nodded her head up and down very wisely.

"This child is wet. Take her clothes off, put her to bed, and a hot basin of bread-and-milk and a good sleep will prevent a chill."

The child's peal of delighted laughter rang through the room.

"Is that what he would say to me? Why, rain and water is nothing important to me! I get drowned nearly, over and over again."

"All the same you are making pools over my carpet. I must suggest that you have your kilt dried and then come and have tea with me. You can tell me then what possessed you to take a boat out on a day like this."

"I'll go to Granny in the kitchen."

She darted out as quickly and lightly as a bird. Rowena was always fond of children, and she felt strangely drawn to this little person. There was something in her small finely-cut face and blazing brown eyes which was very attractive.

"Why," said Rowena to herself, "she must be General Macdonald's neglected child! She speaks very good English. I had no idea she was so big."

It was some little time before Mysie returned, and when she did so she was wrapped round in one of Granny's red flannel petticoats. She seemed quite proud of her attire.

"My kilt is steaming like a kettle! It's filling the kitchen with its smoke! Granny has put it before the fire."

She was dancing round the room as she spoke; then caught sight of Shags, and sitting down on the floor, she took him on her lap and cuddled him.

"He is a bonny thing!" she cried.

"Do you know you might have been drowned this afternoon?" Rowena said gravely. "If I hadn't seen you through my glass and sent the boat out, what would you have done?"

Mysie looked up rather carelessly.

"Nan tells me I have nine lives like a cat. I am thinking Angus would have come after me. He's a Macdonald, you know, and loves Dad. It was really the oars' fault, they weren't able to beat through the waves prop'ly—and then they hurt my hands awful!"

She held up two little blistered palms.

"I took the boat when nobody was looking. I've never rowed all the way across by myself before, but I thought I could, only the wind came down and spoilt it all. Do you know what my name is?"

"Mysie."

"No—Flora Macdonald."

She put much importance into her tone.

"Do you know about the great Flora Macdonald? We belong to her family—and I was called Mysie Flora, but I like my friends to call me Flora. I mean to do something like she did when I grow up. If a prince doesn't come along, I must find somebody else. I'm hoping a prince—a real prince—may be hiding for his life one day, and then I shall go and help him."

Rowena did not laugh. Voice and face of the little speaker were so solemn.

"I hope you will succeed in your efforts," she said.

The little girl will chattered on.

"I live at the farm over there," she said, pointing out of the window. "It's half-way up the mountain. You can't see us, but we see you. Dad's house is nearly always shut up, but it's to be opened soon. He's coming home. The war made him very ill, and now he's coming for a long rest, Nan says. I'm going to try to manage to live with him, if I can. I think I should like to know him."

"You little old-fashioned piece of goods!" ejaculated Rowena. "Would you like to know me, I wonder?" Mysie nodded.

"I mean to. You'll let me come over and talk to you sometimes."

"Not if it means your rowing yourself across the loch."

"Oh, I ride round on Dibbie. He's the pony Angus uses for odd jobs. Do you know Sir Robert Fraser? He had some ponies on the hills and he said if I could catch one I could have it. But I was too frightened to do it. I always thought I might get hold of the water kelpie by mistake. Do you know about him?"

"I'm not sure that I do."

"Loch Tarlie used to be one of his haunts. Long ago when a Baron lived here, his only little boy and some others were playing about the loch, and they suddenly saw a beautiful little pony jumping about with saddle and bridle, and they tried to catch him and get on him; and they caught hold of his bridle and their fingers were glued to it, and they screamed, and the pony dashed for the loch and dragged them in. But the Baron's little boy knew about the water kelpie and he drew out his dirk and cut off his own hand, and the other boys were drowned and his hand with them, but he was saved."

Rowena made her eyes as big as Mysie's were whilst she narrated this horror.

"And is the water kelpie alive now to this day?" she asked.

"Well, I expect he is. When he's very well-known in one loch he goes to another—but I'm not going to let him catch me."

"Tell me some more stories," begged Rowena.

But Janet appeared with the tea, and the little girl turned her attention to the good things spread out before her.

"I like to know a prisoner," she said, munching a piece of cake thoughtfully; "there was a prisoner on a lake in Switzerland. We've got a picture of him. I think his name was Byron. Mr. Ferguson told me about him."

"You mean the prisoner of Chillon. Byron wrote about him. Who is Mr. Ferguson?"

"He's the schoolmaster over at Abertarlie. He teaches me lessons after school hours. Nan won't let me go to school with the other bairns—I'd like to. How long are you going to be in this prison, and is Niddy-Noddy a policeman?"

"I rather wish he was. Then I could run away from him. He's a wise old doctor who has tied me down to my bed, and told me to stay in it for a year! How would you like that? Never to be able to run about out-of-doors, or even change your room."

"It's horrible!" exclaimed Mysie. "Are you really tied to it?"

"By my honour," said Rowena.

"What's that?"

"Well, it's another word for duty. If you make a promise, you must keep it, or you lose your honour. And it's a mark of a true gentleman and lady to keep their honour unsoiled."

"I don't want to be either," said Mysie promptly. "I want to be a boy."

When tea was over Granny came in.

"I've been thinking, mem, it will be Anne Macdonald that will be anxious—an' Colin be drivin' for some corn—the t'other side o' the loch—and Mysie can just ride off wi' him."

Mysie made a grimace in the old woman's face.

"I'm all right here for a wee bit," she said.

But Granny was quite firm, she took her off to get into her kilt, which was dry by this time; and then brought her in to say good-bye to Rowena.

"You must come again soon and see me," Rowena said; "you've brightened up an hour for the poor captive."

Mysie laughed.

"And will you call me Flora?"

"Good-bye, Flora. Take care of yourself. We are going to be friends."

The little girl departed. Granny came in to talk about her when she had gone.

"Who teaches her such good English?" asked Rowena. "I pictured her a little heathen savage, brought up in a crofter's hut."

"Ah, indeed and indeed no! Anne Macdonald was a schoolmistress before she took service with the laird and his lady, a most superior young woman, and she took charge of the bairn from her birth. Ye see Angus have been the laird's gillie all his life for he was his father's gillie before him, an' Angus an' Anne made a match of it, an' then Angus got the sma' farm ower to Barncrassie, an' when the laird's leddy were in toon the bairn mad' her home wi' 'em. An' then Mrs. Macdonald died, an' the bairn have stayed wi' Anne ever since. She've paid a mighty lot o' attention to Mysie's manners and talk, an' in mony ways the little lassie has been bred more carefully than even wi' her own people—for the laird be a dour silent mon, an' when he's doon for a wee bit time has just shut himsel' awa' from all folk, an' come an' gone like a shadow on the wall!"

"And has he never troubled to see his child? What an unnatural father!"

Granny only shook her head hopelessly, and the conversation ended. Rowena began to look forward to seeing her small visitor again.

CHAPTER III

MYSIE MACDONALD

"O blessed vision, happy child,

Thou art so exquisitely wild,

I thought of thee with many fears

Of what might be thy lot in future years."

Wordsworth.

THREE days afterwards, Mysie made her appearance again.

Rowena found her very good company. She was full of Highland folk-lore and superstition; and was a combination of childish trust in the improbable, and old-fashioned sagacity and shrewdness.

"Have you ever seen any fairies?" she asked Rowena.

"I've heard about them," answered Rowena.

"Yes," sighed the child; "but all the nice things happened long ago. People say now that the fairies have gone away; I'm always watching for them. I went to Inverness one day with Nan. We saw two beautiful things there. One was the statue of Flora Macdonald with her dog—only I wish she'd had her kilt on—I believe she used to wear it when she was quite big! And the other was the Tom na hurisch. And when I saw that I said to myself I'd have one for everything that dies."

"What is it?" asked Rowena. "I have never seen Inverness."

"Tom na hurisch is the Fairies' Hill, and they've buried people all over it now. I hope the fairies like it. I think they like people's souls better than their bodies. You know it used to be rather dangerous for people to walk over their hills. They stole their souls out of them. A minister was found one day—at least his body was—and they thought he had had a fit; he wouldn't speak or look or eat, and they took him home; he had been walking round Tom na hurisch—and the fairies kept him out of his body for three days, and then they brought him back. I can't think why he couldn't have remembered what they did with him; he would never talk about it, but he would never go near a Tom na hurisch again—never—all his life long! I wish the fairies would take me one day."

"I would rather not have the experience," Rowena said, laughing. "Who tells you all these stories?"

"Oh, Angus—him and me, we walk over the hills together; and he talks and I listen. Nan laughs at his stories. Nan is an unbeliever! I lie down under the bracken sometimes and watch for the little folk, but I never see them. I thought I did once."

"You will one day! I wonder if you have heard the story of the laird out hunting. He was coming through his glen when he heard the most beautiful pipes playing; and he hid himself behind a tree; and he saw the fairies marching by, and their pipes playing as they went. The pipes shone in the sun, they were silver pipes with glass at the end of them. And the laird suddenly sprang out and threw his bonnet at them, and seized one of the pipes, calling out, 'Mine to yours, and yours to me!' And he wrapped the pipes up in his plaid and took them carefully home, and when he opened them there were some wisps of grass and a puff-ball at the end of them!"

Mysie listened breathlessly.

"Of course they wouldn't have been fairy pipes, if they hadn't been able to change. Fairies always play tricks like that. Did he never get his bonnet back again? I expect the fairies used it to sleep in. It would keep them warm on a wet night. Do tell me some more stories."

So Rowena produced all the fairy stories she could think of, and Mysie drank them in like water.

One day she arrived over in a breathless state of excitement.

"Dad is coming to-morrow. He has been ill since the war, and he's been from one hospital to another; and now he's well again, only he wants to get away from people, and have a rest and quiet. He told Nan so in a letter. She's to get the house ready, and she's not to tell anyone that he's coming."

"And here have you told me!"

"So I have! What a pity! But you're in your prison. I call you the prisoner of Tarlie. You won't tell anybody, will you? It's to be a secret. And I've quite made up my mind to get into his house and see him one day. I shan't mind if he points a pistol at me!"

"At his own child! Is he a pirate king?"

"No—but he's a Macdonald."

Here the child threw her curls back and raised her head almost haughtily. "Angus tells me stories of all that the Macdonalds have said and done. He is one himself, so he kens well. And they never let anyone defy them or get the better of them, and Dad doesn't want to see me. He has said it when Nan has asked him. He would like me swept away!" Here she threw out her small arms tragically. "But I mean to know him. I shall make him speak to me. I ought to be living in his house, not with Nan."

Rowena looked at her with wonder.

"You are growing," she said; "but you are still a baby in years, and your father knows it. Do you want to be sent to school? I suppose by rights you ought to be there now. I can't think how you have escaped the school authorities!"

"But I told you; I learn lessons with the schoolmaster."

"Oh, so you do; I had forgotten. Well, I hope you and your father will have a happy meeting."

With a little wistfulness in her eyes, Mysie went down on her knees beside Rowena's couch. Putting her arms round her neck she whispered:

"Do you think it could happen that he might love me?"

"I think it more than likely," said Rowena, kissing her as she spoke.

And then Mysie sprang up and danced out into the sunshine.

"I have ridden over to tell you, and now I am going back to Nan; for I am going to help her get his house ready."

Rowena lay on her bed looking out on the still blue and trying to recall the Hugh Macdonald she had once seen at her brother's table. It was long ago before he had married, and he was then a thin eager-faced youth, with stern features and a very decided will of his own. He had been abroad for a good many years since then. And his marriage had altered him, people said. She had a dim recollection of a walk round the loch after dinner; but she was quite a young girl at the time. He had not impressed her, except perhaps that he had been too old in his ideas her then.

"If he doesn't own that child, he ought to be ashamed of himself!" she muttered, and then a sudden restless fit took possession of her.

"I am like a mummy. I cannot stay indoors longer. It is breathless to-day. I will write to Noddy and demand release."

She wrote; and by return received 'the usual kind letter from the old doctor, saying that he had written to a local practitioner and had asked him to call and see her and give her his advice. The very next day the doctor appeared. He was a young man and arrived in his car, for he lived about fifteen miles away from her.

Rowena felt impatient as he put her through a regular catechism as to the beginning of the trouble.

"I have been pulled about by all the specialists in town," she said. "I was not going to give up my freedom without a struggle; but they one and all said the same thing—that I must lie on my back for at least a year. I am not rebellious about that; but I can lie on my back out-of-doors as well as indoors, and I am an out-of-door sort of person."

"There is not the slightest reason why you should not do it," the young doctor said decidedly; "didn't you say you had an invalid chair? Let me look at it."

"Mrs. Mactavish will show it to you."

He went out and was some time inspecting it. Then he came in.

"Your chair can be adapted easily to your needs. I know a clever young carpenter, and I'll send him over to tinker it up, and lower the back, till you can lie flat upon it; then you can be out all day."

"I want to vary my life, and sometimes lie out in the boat," said Rowena. "Can you manage that for me?"

"Easily. You must have a flat-bottomed punt and a mattress. Have you anyone who can carry you? We want to prevent the jar to your spine that would be the result of your putting your feet to the ground."

"I have two men who will manage that. Well—you have given me new life! I am very grateful."

Young George Sturt looked at her with a smile.

"I should say you enjoy every moment of your existence," he said, "from your looks."

"My looks are deceptive," Rowena assured him. "I am eaten up at times with an overwhelming envy for every one who can get about on his two legs. And I rage at my fate, and make myself furiously disagreeable to all who come my way."

He laughed, gave her a little sound advice and took his departure. Rowena seized hold of Shags and hugged him.

"Shags, my angel, you and I are going to be Dryads. Wet or fine we will live out-of-doors. My hopes are now fixed upon the carpenter; only I mustn't land poor Ted in too much expense over me. Otherwise I should wire to Glasgow for a flat-bottomed punt immediately. It's a pity we don't possess one."

But when she interviewed Duncan a little later, she was reassured on that point, for he told her he knew a man who owned one and who would be glad to hire it to her for the season.

Mr. Sturt was as good as his word. The carpenter appeared and in a couple of days had done all that was required to her chair. It was a happy moment when she was lifted upon it and wheeled out upon the lawn. The weather was perfect: still and warm with an occasional gentle breeze from the lake.

Rowena lay still, inhaling the sweet air in a state of blissful content. Granny was delighted to see her there; and for three days from nine o'clock in the morning till nine at night, Rowena enjoyed life in her cushioned chair. On the third afternoon about half-past three, just at the drowsiest time in the whole of that summer's day, a stranger walked briskly up the drive and rang at the front door. Rowena was fast asleep; she had neither seen nor heard his approach. She was roused by Granny's gentle voice at her side.

"If you please, mem, 'tis the laird himself—he hav' come over on a question about his shootin' at Tarlie Bottom. He was onawares any of the family were here, so maybe ye'll be answerin' him ye'self. It's wanting to know if it's let, he is."

"Is he here, Granny?" Rowena asked, rousing herself.

"He's waitin' i' the hoose."

"Then ask him to come out here."

In a few moments a tall dark-featured man was standing by Rowena's chair, looking down on her with pity and concern in his eyes.

Rowena held out her hand and smiled in her radiant fashion.

"I am an old crock, but I can talk if I can do nothing else. We do know each other, though it is many years since we met. May I welcome you back? You have been away a long time, have you not?"

"I remember you well," was his prompt reply. "I only saw you once, but your eyes haunted me. I have never seen such joyous ones since; and they are still the same. What has happened to you, may I ask?"

"A spill out riding."

"But you're not alone here? Where's your brother?"

"In India. I am carrying out my doctor's directions. I have no temptations in this quiet spot to evade them. Will you sit down?"

He took the garden chair close to her.

"I am sorry for you," he said with feeling in his tone, "I was a crock for eighteen months in hospital after 1915, so I know what bed is. I never left it for twelve solid months."

"That is my time—a year—and then I hope I shall be cured."

His whole face softened.

"Ah," he said, "when you've suffered yourself, you can feel for others."

"Yes—and I dare say I was in need of a more sympathetic spirit," said Rowena thoughtfully. "I have always laughed too much. I laugh at myself now. You want to know about our shooting. Ted has let it, I am afraid."

They began to talk over estate matters, and then about sport in general. He seemed in no hurry to go; and presently began to revert to his own state of health.

"I am only here to patch myself up," he said. "But they've chucked me out of the army—let me retire as Major-General. I suppose I ought to feel my life is over; but my brain is sound, and it makes me rage at times. What shall I do with myself here? Only vegetate."

"Oh, no; if you are a reader, you won't do that. It's wonderful how much fuller we can store our brains than we do! I cannot fill my empty cells fast enough! Have you any hobbies?"

He shook his head.

"I'm a reader of sorts. I couldn't have lived through my eighteen months without books."

Then Rowena said suddenly: "Have you seen your child?"

His brows contracted.

"No. I've told her nurse I'll see her in a day or two. I've been busy. Children aren't in my line."

"She's a little person of much character," said Rowena slowly. "I don't want to be an interfering meddler, but you'll gain by her acquaintance. I have."

He raised his eyebrows and then smiled.

"I am talking to you like an old friend. If you had been well and jolly, I should have cut and run. I have taken a dislike to my fellow-creatures, especially the sound and healthy ones. And to my disgust I'm nervy—children would get on my nerves. I'll see her when I feel fitter. You consider me an inhuman parent, I can see."

"No, only an ignorant one," said Rowena. "Your little daughter has made some of my worst days very bright."

"Women always worship babies."

"She is companionable, you will find."

His brows did not relax; he leant back in his chair and drew a long breath.

"Her existence brings back some bad times. Her mother hated me, you know. It was the first thing she said to me after the birth of the child. We couldn't pull together, though God knows I tried hard. And poor Evie was forced by her mother to marry me, I heard afterwards. Well, she didn't have a long time with me, poor soul!"

Then he pulled himself up. "I am getting garrulous. I don't generally give way to such personal reminiscences, but I want to explain my want of interest in the child. I was always told she was the picture of her mother."

"But my good man," said Rowena quickly, "bodies may resemble each other, but very seldom souls. And Mysie is—well, I will leave you to find out. This much I will tell you, that she is hungering for your interest and affection. Give her a chance—and yourself too."

He did not reply for a few minutes; then he said rather irrelevantly: "You say you're a reader. Have you enough books to keep you occupied? Because my father bequeathed to me a very fine library. I have been overhauling it and can lend you anything you want."

"Oh, how truly kind!"

With animation Rowena began discussing books, and half an hour slipped by before her visitor attempted to make a move.

He would not stay to tea. As he stood up, he looked down at Rowena with some softness in his grey eyes.

"You don't want to be bucked up," he said, "for you are the essence of cheerfulness. When I have my bad bouts of pain, I think of the thousands of paralysed bedridden young men who have had their health and strength taken from them with one fell swoop in the war, and feel an old crock like myself has no right to grouse. I have done my work, and am wanted by no one!"

"You are wanted by your child!" said Rowena firmly.

He gave a short laugh.

"What a pertinacious woman you are! Are you bored by visitors? May I walk over again, and bring you the books you want?"

"Yes, certainly. I shall be delighted. And then you can give me your impressions of Mysie!"

He departed, but Rowena gave a little sigh as she looked after him and noted the tired bend of his shoulders, and his rather uncertain steps.

"Poor lonely unhappy man!" she murmured. "Why, Shags, you and I must try to bring some zest for living into his soul. I rather fancy Mysie will have a say in that."

Shags cocked one ear and looked wise. He had already had some experience of Mysie. She had certainly contributed towards his pleasure, for she and he invariably had a romp together when she came over.

Two or three days passed. Then one morning Mysie arrived over on her pony. She threw herself upon Rowena in her usual impulsive fashion.

"Haven't you longed to see me! It's been such an exciting time! And I heard Dad say he was coming to see you this afternoon, so I thought I would get over first."

"Now sit up and tell me all about it from the very beginning," demanded Rowena.

"The beginning," said Mysie importantly, "was when Nan came back from the house and said I was to go up and see Dad in the morning. Of course I'd seen him lots of times before that, but I took care that he shouldn't see me. I wanted to find out if I'd like him for a father. I saw him with his gun, he shot two pigeons, and I clapped my hands once. I was behind a tree, and he looked round quickly, but he didn't see me. When Nan wanted to dress me up, I said, No—I would go in my kilt. I hate girls' frocks, and so I ran straight away from her, and walked into the house by myself. And fancy! It was eleven o'clock, and Dad was eating his breakfast!"

"And what did you say?"

"I said, 'Good morning, Dad; may I have some of your bacon?' and I sat down and he laughed, and gave me a big plateful, and told them to bring me a cup of coffee. And then he said:"

"'I don't know whether I'm looking at a boy or a girl,' and then I told him, very earnest, that I had a boy's heart and a girl's body, and then I gave him my present I had brought with me. It was two darling little trout I had caught the day before with Angus. And he was quite pleased and asked me whether I liked fishing, and I told him I liked everything he did, and so we settled up then that we would do things together, and then I told him he'd better let me have a bedroom in his house so that I needn't be running backwards and forwards all day long—and he said yes to that. After that we talked like anything. Why, he's almost as good to talk to as you are!"

"He must be good then!" said Rowena, laughing. "I think he is a delightful father to have, Flora."

"Oh, yes; and we talked about my name—he doesn't like the name of Flora. I said I'd rather be called Macdonald than Mysie, and he thinks he can manage to call me Mac. But he doesn't care to talk all day long, he says, so I've left him. I dare say he'll get used to me after a bit, but he finds me stranger than I do him, you know. For I've always talked to Angus—he's a man, of course, but Dad says he isn't used to children, and doesn't understand them!"

Mysie paused for breath; her eyes glowed as she went on:

"If Dad and I live together and do things together, I shall thank God truly! I've prayed to have a proper father since I was a baby. And after breakfast I went upstairs and told Dad the room I would like to sleep in. Nan says I can't leave her, and Dad doesn't mean it. But he and me mean it very certainly!"

"Ah," said Rowena, "I can see that you're going to have a real good time now. But don't worry a man when he's seedy. Your Dad will have days when he wants to be alone."

Mysie was too full of her own thoughts to take this in.

"I told him there was a prisoner on the loch and that I went to see her, and he seemed to guess at once, and he told Angus he was coming over here this afternoon."

Mysie chattered on: she described her father's appearance with minute details; she said she would like him best in a kilt and hoped he would soon wear it. And she finally departed apologizing for her short visit.

"I feel I don't want to stay away from him too long," she said; "in case he may forget me again."

In the afternoon General Macdonald appeared with his pockets bulging with books. Rowena received him and his books with much pleasure.

"I have seen my child," he said abruptly. "She is bigger and older than I thought. She means to take possession of me. I fancy she ought to be at school, ought she not?"

"Oh, don't worry over school just yet. Get to know her, and get her to know you. What do you think of her?"

He drew up a chair and sat down upon it. Rowena waited for him to speak, and he kept her waiting for three or four minutes, then he said slowly:

"I am a little afraid of her."

"What nonsense!"

"I am afraid of her personality. She does not mean to remain in the background. And when I came down here, a child did not enter into my calculations."

"But I really think she ought to have done so. May I congratulate you upon having such a child?"

He looked at her and smiled.

"I see she has won your heart. A man is handicapped when he has to train a girl child. And she wants training. If she had been a boy, I would have found the task easier."

"Oh, don't take her so heavily," said Rowena. "Let her trot round with you, and do things with you. She'll learn from your talk what is right and wrong."

"Will she? I'm a poor specimen at the best; and I know nothing of women and their ways."

"Bring her up as a boy, then," said Rowena, laughing at his forlorn tone. "She is, as she says, half a boy already. Don't act the heavy father. Of course she will have to be educated later on. But let her have a holiday with you now. Do you know she has prayed that she might have a 'proper father' from the time she was a baby? Don't disappoint her. And when she worries you, send her over to me. Shags and I understand her."

"May I smoke?" the General asked.

Rowena looked at him with laughter in her eyes, as he slowly produced a favourite pipe out of his pocket.

"I suppose," he said reflectively, "you can't mould children as you wish. They resist now, more than they used to do. I should like to mould her after the pattern of my mother. I don't want to have one of these self-assertive modern young women as my daughter, later on."

"I am afraid Mysie has too much character to be shaped into another person's mould. But she is warm-hearted, and if a girl loves, she can be governed through her love."

There was silence between them.

Then Rowena said:

"We might be two old spinster governesses sitting up and discussing the character of our pupils! Look over the loch at the afternoon shadows on the hills. Sweep your small daughter out of your mind for a moment or two—and tell me if that sky doesn't bring delight to your soul?"

General Macdonald gave a short quick sigh, but as he looked across the blue loch, the lines about his lips relaxed.

"Ah," he said, "it's good to get back to it again. There's no place like the Highlands in the world."

"To-morrow," said Rowena blithely, "I am going to extend my horizon. If you see a doubtful-looking craft upon the surface of the loch, it will be me, lying on my back in a flat-bottomed punt. We may fly a scarlet sail. Colin will be with me. But I assure you it will be a red-letter day in my life—therefore the red flag, you see!"

"I congratulate you. But don't put me off my child, for I assure you I hardly slept last night for thinking about her. Knocking about in hospitals, as I have done, I have seen all sorts and conditions of women. I have been bossed by some, and petted by others, and the audacity of some young women filled my soul with awe. Do you think that women—girls, I should say—ought to be trained to earn their own living, so as to be independent of our sex? As I heard some of the nurses declaiming against their dull homes, I gave a thought sometimes to their dull old parents. I shall be one of them when my girl grows up. How can I expect her to stay at home with me, if all the young world is out and away from their homes?"

"By the time Mysie is grown-up the swing of the pendulum will be back the home way again," said Rowena. "I have had great longings for work, you know, and tried to break away from my brother's house more than once. I did leave them for eight months once, but was called back again by my sister-in-law's serious illness. Nothing will keep a girl at home if she wants to leave it, except circumstances. As I say, be a chum and companion to Mysie and she'll never want to leave you, until a possible husband turns up. She is prepared to idealize and worship you. Let her do it, and do, if you want to win her heart quickly, call her 'Flora'!"

General Macdonald laughed.

"Ah, we've fallen out already over that. 'Mysie' was my mother's pet name."

"Then keep it sacred," said Rowena, "and call your small girl by the name she adores and loves!"

They talked on; gradually Rowena got his mind upon other subjects. When he left her, he gripped her hand until she could have cried with the pain of it.

"You have helped me enormously," he said. "I am not going to fight shy of my responsibility as a father any longer."

"Shags," said Rowena, taking hold of a golden brown ear, "am I a hundred years old? Is it always the role of a person on her back to dole out advice to her visitors? Am I, a single woman, to occupy my leisure thoughts in studying a child's character, and the suitable training for her? I am going now to read the most frivolous book I have by me, just to forget the moralities and gravity of life, and to imagine myself a young dog like yourself."

CHAPTER IV

THE BIRTHDAY GIFT

"A glory gilds the sacred page,

Majestic like the sun

It gives a light to every age;

It gives, but borrows none."

Cowper.

ROWENA was moved into her boat the next day. And the sun shone down upon her in real friendliness. Of course Shags accompanied her; and for a couple of hours Colin rowed her over the loch; then, feeling she must not take him longer from his work in the garden, she made him moor the boat to the side of the small landing pier, and there, with her hands dabbling in the cool water, Rowena lay and meditated, and read for another couple of hours. She hardly knew which she liked best, the motion or the stillness.

Granny came out at tea-time and suggested her moving in.

"I could stay here for ever and ever!" exclaimed Rowena. "What is it about the loch that sends such peace and rest into one's soul?"

"It's the still waters," said Granny. She murmured to herself, "'He leadeth me beside the still waters.'"

Rowena never took any notice when the Bible was quoted to her.

"Couldn't I lie here all night?" she said.

"'Deed, an' no, ye will not do that, mem. An' wha would say hoo lang this stillness would be! A storm would come on, and then where would ye be? A helpless leddy, solitary in the nicht!"

"Oh, Granny, what a description! Well, this helpless body must be moved in to bed, I suppose. I can look forward to to-morrow."

But the next day was cold and wet. Rowena by this time was accustomed to the Highland weather. She had a small wood fire made in her green room, and with her books and rug-making spent a very pleasant day. Between four and five the rain ceased and the sun shone out. And soon after five, a motor full of people drove up to the door. It was Lady Fraser, their nearest neighbour. She had brought her daughter and niece over, and two young friends of theirs.

Rowena was not sure whether she liked them pouring in upon her, but she knew it was real friendliness and good nature that brought them.

"We heard of your accident, and your brother told my husband before he went to India that you would be staying here on the quiet for the summer; so we promised him we would look after you, and prevent you from being dull."

Lady Fraser paused at the end of this speech.

"We hoped you might have been able to come over to us, perhaps. We did not know you were a real invalid."

"I am a prisoner for a year," said Rowena cheerfully, "and I am taking fresh views of life. It's astonishing what a different environment does for one. I shall be delighted to see you when you have time to come over, but I cannot return your visits."

"There seem so many invalids now," said Lady Fraser with a sigh. "There is Hugh Macdonald. We heard he had returned home, and wrote asking him to dinner to-morrow, He replied that he was not well enough to go anywhere; but my son George saw him fishing yesterday and he had a child with him. I suppose it is his little girl. I should think she ought to be educated. He has let her run wild since her mother's death. Well, I am truly sorry for you, my dear. I should think it a deadly existence here by yourself. But you say you don't mind."

The girls were full of commiseration. They had always regarded Rowena before as being great fun, and very sporting. She felt that, though they did not put it into words, her invalid life at present formed a gulf between her and their pleasure-loving souls.

"It's so tiresome," said Katie Fraser; "so many of the men are grumpy now like General Macdonald. George is very much the same himself—says tennis and games are boring, and fatigue him. He likes to moon about and go off alone with the keepers."

"My dear," said Lady Fraser, "you forget how ill he has been."

"And the horrors he has gone through," said Rowena slowly. "Forgetfulness is not easy to them all."

"Oh, we will teach them to forget," laughed one of the girls. "They must have a good time now, to make up for all they have lost."

"We're going to get up a pastoral play the end of August," said Lady Fraser; "there will be more people down here then. I do hate the empty time up here, don't you?"

"Well, I'm looking forward to spend the winter here," said Rowena.

They screamed at that statement.

"You can't! Nobody lives here in the winter. You had better be buried at once."

"Why, you will have no neighbours at all! All the houses are shut up!"

"I shall have the minister and his mother; the doctor; Granny Mactavish and her niece, and I can tick off five farms round our loch which will not be shut up! You seem horror-stricken, but I mean to cultivate my neighbours, whoever they may be, if they will be good enough to cultivate me!"

Lady Fraser shook her head at her. "You are joking at our expense! Your eyes betray you!" Her girls were mute, but they looked at Rowena pityingly.

They did not stay very long. She watched them drive off, with a grim smile, and said to Shags:

"We understand now, Shags, how unpleasant perfectly strong healthy people are to the sick. I don't wonder that Hugh Macdonald has taken a dislike to them. I suppose it is their pity which makes me grind my teeth. I always think there's a bit of contempt mixed up with it. Now I am perfectly certain I shan't be troubled with the Frasers much, and how they used to live here last summer! What fun we did have! It is a deadly existence, of course, but content is creeping over me, and I shall not be disturbed."

She returned to her books, but a restless wave passed over her; then she called Granny to the rescue, and a talk with her restored her equanimity of mind.

The next day was windy; she was unable to be in her boat, but she was able to lie out in her chair. And in the afternoon, who should appear but Mysie and her father! They were riding. Mysie's face was glowing with happiness and importance. Her father looked as grave and imperturbable as ever. Mysie in her usual impulsive fashion flung herself upon Rowena.

"Oh, I'm so glad to see you again! And such quantities have happened! Dad doesn't think I'm bad for my age! He really doesn't. I caught a bigger fish than him yesterday morning. We went out in all the rain and did it! And do tell me, were you lying in your boat the day before yesterday? I looked through Dad's glasses and thought I saw you. And may I come by your side in my boat and then I'll tie you up to me and tow you? It will be fun!"