The Life and Times of Col. Daniel Boone, Hunter, Soldier, and Pioneer

Edward S. Ellis

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Life and Times of Col. Daniel Boone, Hunter, Soldier, and Pioneer, by Edward Sylvester Ellis

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/lifetimesofcolda00elli |

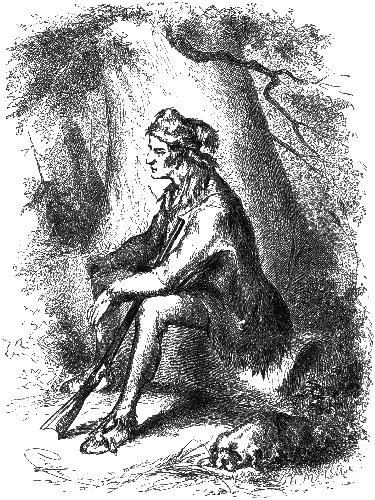

Daniel Boone.

THE LIFE AND TIMES

OF

Col. Daniel Boone,

HUNTER, SOLDIER, AND PIONEER.

WITH

SKETCHES OF SIMON KENTON, LEWIS WETZEL, AND OTHER

LEADERS IN THE SETTLEMENT OF THE WEST.

Who passes for in life and death most lucky,

Of the great names which in our faces stare,

Is Daniel Boone, backwoodsman of Kentucky.

Of solitude. Health shrank not from him, for

Her home is in the rarely-trodden wild."

By EDWARD S. ELLIS,

AUTHOR OF "THE LIFE OF COLONEL DAVID CROCKETT,"

"NED IN THE BLOCK-HOUSE," "NED IN THE WOODS," ETC.

PHILADELPHIA:

PORTER & COATES.

Copyright, 1884,

BY

PORTER & COATES.

INTRODUCTION.

DANIEL BOONE was the ideal of the American pioneer—brave, cool, self-reliant, a dead shot with his rifle, a consummate master of woodcraft, with sturdy frame, hopeful at all times, and never discouraged by disasters which caused many a weaker spirit to faint by the way. All that the pen of romance depicts in the life of one whose lot is cast in the Western forests, marked the career of Boone. In the lonely solitudes he encountered the wild animal and the fiercer wild man; and he stood on the bastions at Boonesborough through the flaming sun or the solemn hours of night, exchanging shots with the treacherous Shawanoe, when every bullet fired was meant to extinguish a human life; he was captured by Indians three times, his companions were shot down at his side, his daughter was carried away by savages and quickly rescued by himself and a few intrepid comrades, his oldest boy was shot dead before he set foot in Kentucky, and another was killed while bravely fighting at Blue Licks; the border town named after him was assaulted and besieged by overwhelming bodies of British and Indians, his brother was slain and he himself underwent all manner of hardship and suffering.

Yet through it all, he preserved his honest simplicity, his unswerving integrity, his prudence and self-possession, and his unfaltering faith in himself, in the future of his country, and in God.

He lived through this crucial period to see all his dreams realized, and Kentucky one of the brightest stars in the grand constellation of the Union.

Such a life cannot be studied too closely by American youth; and in the following pages, we have endeavored to give an accurate description of its opening, its eventful progress and its peaceful close, when, in the fullness of time and in a ripe old age, he was finally laid to rest, honored and revered by the great nation whose possessions stretch from ocean to ocean, and whose "land is the fairest that ever sun shone on!"

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Birth of Daniel Boone—Fondness for Hunting—An Alarming Absence—A Pedagogue of the Olden Time—Sudden Termination of Young Boone's School Education—Removal to North Carolina—Boone's Marriage—His Children | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Social Disturbances in North Carolina—Eve of the American Revolution—Boone's Excursions to the West—Inscription on a Tree—Employed by Henderson and Company—The "Regulators" of North Carolina—Dispersed by Governor Tryon—John Finley—Resolution to go West | 11 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Party of Exploration—Daniel Boone the Leader—More than a Month on the Journey—On the Border of Kentucky—An Enchanting View—A Site for the Camp—Unsurpassed Hunting—An Impressive Solitude—No Signs of Indians | 19 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Boone and Stuart start out on a Hunt—Captured by Indians and Disarmed—Stuart's Despair and Boone's Hope—A Week's Captivity—The Eventful Night | 28 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Escape—The Hunters find the Camp Deserted—Change of Quarters—Boone and Kenton—Welcome Visitors—News from Home—In Union there is Strength—Death of Stuart—Squire Boone returns to North Carolina for Ammunition—Alone in the Wilderness—Danger on Every Hand—Rejoined by his Brother—Hunting along the Cumberland River—Homeward Bound—Arrival in North Carolina—Anarchy and Distress—Boone remains there Two Years—Attention directed towards Kentucky—George Washington—Boone prepares to move Westward | 34 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Leaving North Carolina—Joined by a Large Company at Powell's Valley—Glowing Anticipations—Attacked by Indians in Cumberland Gap—Daniel Boone's Eldest Son Killed—Discouragement—Return to Clinch River Settlement—The Check Providential—Boone acts as a Guide to a Party of Surveyors—Commissioned Captain by Governor Dunmore, and takes command of Three Garrisons—Battle of Point Pleasant—Attends the making of a Treaty with Indians at Wataga—Employed by Colonel Richard Henderson—Kentucky claimed by the Cherokees—James Harrod—The First Settlement in Kentucky—Boone leads a Company into Kentucky—Attacked by Indians—Erection of the Fort at Boonesborough—Colonel Richard Henderson takes Possession of Kentucky—The Republic of Transylvania—His Scheme receives its Death-blow—Perils of the Frontier—A Permanent Settlement made on Kentucky Soil | 46 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Boone Rejoins his Family at the Clinch River Settlement—Leads a Company of Immigrants into Kentucky—Insecurity of Settlers—Dawn of the American Revolution—British Agents Incite the Indians to Revolt against the Settlements | 61 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Comparative Quiet on the Frontier—Capture of Boone's Daughter and the Misses Callaway by Indians—Pursued by Boone and Seven Companions—Their Rescue and Return to their Homes | 69 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| General Uprising of the Indians—The Border Rangers—Attack upon Boonesborough—Repulse of the Assailants—Second Attack by a Larger Force and its Failure—Arrival of Forty-five Men—Investment of Logan's Fort—Timely Arrival of Colonel Bowman with Reinforcements—Attack upon Harrodsburg | 79 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| A Diner-out—The "Hannibal of the West"—Election of General Clark and Gabriel Jones as Delegates to the Virginia Legislature—Their Journey to the Capital—General Clark obtains the Loan of a Large Supply of Ammunition—Erection of the County of Kentucky—General Clark attacked and pursued by Indians on his Voyage down the Ohio—Conceals the Ammunition and delivers it safely at the Border Stations—General Clark marches upon Kaskaskia and captures the obnoxious Governor Rocheblave—Governor Hamilton of Detroit organizes an Expedition against the Settlements—General Clark captures Fort St. Vincent and takes Governor Hamilton a Prisoner—Captures a Valuable Convoy from Canada and Forty Prisoners—Secures the Erection of Important Fortifications by Virginia | 85 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Boone leads a Party to the Blue Licks to make Salt—Capture of Boone and Surrender of the Entire Party—Conducted to Detroit—His Captors Refuse to Exchange him—He is Adopted by the Shawanoes—He discovers a Formidable Expedition is to move against Boonesborough—The Attack Postponed—Boone leads a Party against an Indian Town on the Scioto—Encounter with a War Party—Returns to Boonesborough—The State Invested by Captain Duquesne and a Large Force—Boone and the Garrison determine to Defend it to the Last—Better Terms Offered—Treachery Suspected—The Attack—The Siege Raised | 96 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The Peculiar Position of Boonesborough—Boone rejoins his Family in North Carolina—Returns to Boonesborough—Robbed of a Large Amount of Money—Increased Emigration to the West—Colonel Rogers and his Party almost Annihilated—Captain Denham's Strange Adventure | 112 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Colonel Bowman's Expedition—Its Disastrous Failure—Death of Boone's Son—Escape of Boone—Colonel Byrd's Invasion—Capture of Ruddell's and Martin's Station—Daring Escape of Captain Hinkston | 120 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Colonel Clark's Invasion of the Indian Country—Boone is Promoted to the Rank of Colonel—His Brother Killed at Blue Licks and Boone narrowly Escapes Capture—Attack upon the Shelbyville Garrison—News of the Surrender of Cornwallis—Attack upon Estill's Station—Simon Girty the Renegade—He Appears before Bryant's Station, but Withdraws | 130 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Arrival of Boone With Re-enforcements—Pursuit of the Indian Force—Boone's Counsel Disregarded—A Frightful Disaster—Reynold's Noble and Heroic Act—His Escape | 136 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| General Clark's Expedition—A Dark Page in American History—Colonel Crawford's Disastrous Failure and his own Terrible Fate—Simon Girty | 144 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Adventures of the Spies White and M'Clelland—Daring Defence of her Home by Mrs. Merrill—Exploits of Kernan the Ranger | 155 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| The Three Counties of Kentucky united into One District—Colonel Boone as a Farmer—He outwits a Party of Indians who seek to capture him—Emigration to Kentucky—Outrages by Indians—Failure of General Clark's Expedition | 172 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| General Harmar's Expedition against the Indians—Colonel Hardin Ambushed—Bravery of the Regulars—Out-generaled by the Indians—Harmar and Hardin Court-martialed—General St. Clair's Expedition and its Defeat | 180 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The Brilliant Victory of Mad Anthony Wayne brings Peace to the Frontier—Boone Loses his Farm—He Removes to Missouri—Made Commandant of the Femme Osage District—Audubon's Account of a Night with Colonel Boone—Hunting in his Old Age—He Loses the Land granted him by the Spanish Government—Petitions Congress for a Confirmation of his Original Claims—The Petition Disregarded | 186 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Last Days of Colonel Boone—Reinterment of the Remains of Himself and Wife at Frankfort—Conclusion | 201 |

| GENERAL SIMON KENTON. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Birth of Kenton—Desperate Affray with a Rival—Flees to the Kentucky Wilderness—He and Two Companions attacked by Indians—One is Killed and the Survivors Escape—Rescued, after great Suffering—Kenton spends the Summer alone in the Woods—Serves as a Scout in the Dunmore War—Kenton and Two Friends settle at Upper Blue Lick—Joined by Hendricks, who meets with a Terrible Fate | 207 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Kenton and his Friends Visit Boonesborough—Desperate Encounter with Indians—Proceeds with Two Companions to Reconnoitre an Indian Town on the Little Miami—Captured while Making Off with a Number of Horses—Brutal Treatment—Bound to the Stake and Runs the Gauntlet—Friendship of Simon Girty, the Renegade—Finally Saved by an Indian Trader—Removed to Detroit, and Escapes—Commands a Company in General Clark's Expedition—Receives Good News—Visits Virginia—Death of his Father—Reduced to Poverty—Removes to Urbana, Ohio—Elected Brigadier-General—His Conversion—His Last Days | 222 |

| LEWIS WETZEL. | |

| Birth of Lewis Wetzel—His Father Killed by Indians, and Himself and Brother carried off Prisoners—Their Remarkable Escape—Murder of an Indian—Serves in Crawford's Expedition—Pursued by Four Indians, and Kills Three—Escape from the Custody of General Harmar—Wetzel's Hunts for Indians—Assists a Relative to Recover his Betrothed from Savages—Old Age and Death | 251 |

LIFE AND TIMES

OF

COLONEL DANIEL BOONE.

CHAPTER I.

Birth of Daniel Boone—Fondness for Hunting—An Alarming Absence—A Pedagogue of the Olden Time—Sudden Termination of Young Boone's School Education—Removal to North Carolina—Boone's Marriage—His Children.

Daniel Boone was born in Exeter township, Bucks county, Pennsylvania, on the 11th of February, 1735, so that he was just three years the junior of Washington.

Daniel had six brothers and four sisters, he being the fourth child of Squire Boone, whose father landed at Philadelphia from England, October 10, 1717, bringing with him two daughters and nine sons. The township of Exeter, as it is now known in Pennsylvania, was named by the elder Boone after the city in England near which he was born.

There is good authority for believing that the Boone family, when living in the mother country, were attached to the Established Church; but, when they had resided some time amid the peaceful surroundings and gentle influences of the friends and followers of George Fox, they inclined to their religious belief, though it will hardly be claimed that Daniel Boone continued orthodox throughout his adventurous life.

In those days, the educational advantages given youth were very meagre, and frequently none at all. The old-time pedagogue was a man stern and repelling to children, knowing little of the true means of imparting knowledge. About the only branch he handled with any skill was that which came from the nearest tree; and, had he possessed the ability to teach, he lacked, in the generality of cases, the education necessary.

A century and a half ago, Exeter township abounded with game, and the town itself was a pioneer settlement of the most primitive order, consisting of log-houses almost entirely surrounded by forests, in whose depths roamed bears, panthers, deer, and the smaller game so attractive to sportsmen.

It was these which were to educate young Boone more than were the crude means and the tippling teacher in whose charge he was placed. Nothing delighted the lad more than to wander for hours through the woods, gun in hand, stealing among the cool shadows, behind the mossy rocks and along the purling streams, with the soft tread of the Indian, while the keen eyes of the young hunter searched tree-top and bush for the first signs of game, and his ear was ever strained to catch the cautious footstep of the wild beast as it crept faintly over the leaves.

Thus in the grand school of Nature was the great pioneer trained. While yet a small boy, he became noted for his unerring aim with the rifle, and the skill with which he read the "signs" among the trees, that were as closed volumes to others.

The privilege of wandering with gun and dog was all the happiness he asked, and as an inevitable consequence of this mode of life, he grew sturdy, strong, active, and capable of immense exertion without fatigue. It is in just such nurseries as this that the great explorers and pioneers of the world are educated.

One morning, Daniel shouldered his rifle, and whistling to his dog, the two plunged into the woods for one of their usual hunts. The sun was just rising in a clear sky, the air was crisp and invigorating, and the prospect was all that the heart of the young hunter could wish. Those of his relatives who saw him depart thought nothing of it, for the sight was a very common one with him and his brothers, and young as they were, they learned among the rudiments of their training the great fundamental truth to trust in God and themselves.

As the shades of night closed over settlement and forest, the boy Daniel was expected home, though the family had no special misgiving when the hours passed without bringing him, it being supposed that he had penetrated so far into the wilds that he preferred to encamp for the night rather than take the long tramp home.

But, when the second day had passed, and he failed to appear, the parents were in great distress, for it seemed certain that some fatal accident must have overtaken their child. The mature and experienced hunter is always in peril from wild beasts or the wilder human beings who prowl and skulk through the wilderness, and many a man who has braved the dangers of a score of years, has fallen a victim to the treacherous biped or quadruped, who has sought his life with greater cunning than he has done his own work.

It was impossible therefore for them to feel anything but the most painful anxiety for their boy, and, unable to remain idle longer, they called upon their neighbors, and a search-party was organized.

The trail made by the lad was too faint to be followed successfully, and the parties scattered and hunted for traces as best they could.

Hours passed by, every man doing his utmost to discover the fate of the boy, who they hoped was still living somewhere in the depths of the wilderness, though it would seem scarcely possible that, if alive, he was not in a suffering or helpless condition.

But the shouts and reports of their guns remained unanswered, and they pushed forward, hoping against hope. The bonds of sympathy are nowhere stronger than in such frontier settlements, where a common feeling of brotherhood exists, and the men who were searching for the lost Daniel, were hardly less anxious concerning him than were the parents themselves.

Suddenly someone descried a faint, thin column of smoke rising from a nondescript sort of structure, and hurrying toward it, they saw one of the most primitive of cabins, made of limbs and brush and sods of grass piled together. Stealing around to the rude entrance, they peeped in, and saw Daniel himself, looking like an old hunter who had settled down for the season. On the earth-floor of his structure were strewn the skins of the game he had shot, while he was cooking the choicest pieces before the smoking fire. He was only three miles from home, but it might as well have been a hundred, for all the additional comfort it afforded his friends and parents.

The lad looked up with an expression of surprise, wondering what all the excitement was about; and when he found they were hunting for him, it was hard to understand the necessity for doing any such thing.

It was not the first time he had been alone in the woods, and he thought he was as well able to take care of himself as were any of the older pioneers who came to look for him. However, as he was a dutiful son, and had no wish to cause his parents any unnecessary alarm, he gathered up his game and peltries, and went back home with the hunters.

Nothing can be more pleasant to the American boy than just such a life as that followed by Daniel Boone—wandering for hours through the wilderness, on the look-out for game, building the cheery camp-fire deep in some glen or gorge, quaffing the clear icy water from some stream, or lying flat on the back and looking up through the tree-tops at the patches of blue sky, across which the snowy ships of vapor are continually sailing.

But any parent who would allow a child to follow the bewitching pleasures of such a life, would commit a sinful neglect of duty, and would take the surest means of bringing regret, sorrow, and trouble to the boy himself, when he should come to manhood.

The parents of young Boone, though they were poor, and had the charge of a large family, did their utmost to give their children the rudiments of a common school education, with the poor advantages that were at their command.

It is said that about the first thing Daniel's teacher did, after summoning his boys and girls together in the morning, was to send them out again for a recess—one of the most popular proceedings a teacher can take, though it cannot be considered a very great help in their studies.

While the pupils were enjoying themselves to their fullest bent, the master took a stroll into the woods, from which he was always sure to return much more crabbed than when he went, and with his breath smelling very strongly of something stronger than water.

At times he became so mellowed, that he was indulgence itself, and at other times he beat the boys unmercifully. The patrons of the school seemed to think their duty ended with the sending of their children to the school-house, without inquiring what took place after they got there.

One day Daniel asked the teacher for permission to go out-doors, and receiving it, he passed into the clear air just at the moment that a brown squirrel was running along the branch of a fallen tree.

Instantly the athletic lad darted in pursuit, and, when the nimble little animal whisked out of sight among a dense clump of vine and bushes, the boy shoved his hand in, in the hope of catching it. Instead of doing so, he touched something cold and smooth, and bringing it forth, found it was a whiskey bottle with a goodly quantity of the fiery fluid within.

"That's what the teacher comes out here for," thought Daniel, as his eyes sparkled, "and that's why he is so cross when he comes back."

He restored the bottle to its place, and returned to the school-room, saying nothing to any one until after dismissal, when he told his discovery to some of the larger boys, who, like all school-children, were ever ripe for mischief.

When such a group fall into a discussion, it may be set down as among the certainties that something serious to some one is sure to be the result.

The next morning the boys put a good charge of tartar emetic in the whiskey bottle, and shaking it up, restored it to its former place of concealment. Then, full of eager expectation, they hurried into school, where they were more studious than ever—a suspicious sign which ought to have attracted the notice of the teacher, though it seems not to have done so.

The Irish instructor took his walk as usual, and when he came back and resumed labor, it may be imagined that the boys were on the tip-toe of expectation.

They had not long to wait. The teacher grew pale, and gave signs of some revolution going on internally. But he did not yield to the feeling. As might have been expected, however, it increased his fretfulness, and whether he suspected the truth or not, he punished the boys most cruelly, as though seeking to work off his illness by exercising himself with the rod upon the backs of the lads, whose only consolation was in observing that the medicine taken unconsciously by the irate teacher was accomplishing its mission.

Matters became worse and worse, and the whippings of the teacher were so indiscriminate and brutal, that a rebellion was excited. The crisis was reached when he assailed Daniel, who struggled desperately, encouraged by the uproar and shouts of the others, until he finally got the upper hand of the master, and gave him an unquestionable trouncing.

After such a proceeding it was not to be expected that any sort of discipline could be maintained, and the rest of the pupils rushed out-doors and scattered to their homes.

The news of the outbreak quickly spread through the neighborhood, and Daniel was taken to task by his father for his insubordination, though the parent now saw that the teacher possessed not the first qualification for his position. And the instructor himself must have felt somewhat the same way, for he made no objections when he was notified of his dismissal, and the school education of Daniel Boone ended.

It was a misfortune to him, as it is to any one, to be deprived of the privilege of storing his mind with the knowledge that is to be acquired from books, and yet, in another sense, it was an advantage to the sturdy boy, who gained the better opportunity for training himself for the great work which lay before him.

In the woods of Exeter he hunted more than ever, educating the eye, ear, and all the senses to that wonderful quickness which seems incredible when simply told of a person. He became a dead shot with his rifle, and laid the foundations of rugged health, strength and endurance, which were to prove so invaluable to him in after years, when he should cross the Ohio, and venture into the perilous depths of the Dark and Bloody Ground.

Boone grew into a natural athlete, with all his faculties educated to the highest point of excellence. He assisted his father as best he could, but he was a Nimrod by nature, instinct and education, and while yet a boy, he became known for miles around the settlement as a most skilled, daring, and successful hunter.

When he had reached young manhood, his father removed to North Carolina, settling near Holman's Ford, on the Yadkin river, some eight miles from Wilkesboro'. Here, as usual, the boy assisted his parents, who were gifted with a large family, as was generally the case with the pioneers, so that there was rarely anything like affluence attained by those who helped to build up our country.

While the Boones lived on the banks of the Yadkin, Daniel formed the acquaintance of Rebecca Bryan, whom he married, according to the best authority attainable, in the year 1755, when he was about twenty years of age.

There is a legend which has been told many a time to the effect that Boone, while hunting, mistook the bright eyes of a young lady for those of a deer, and that he came within a hair's-breadth of sending a ball between them with his unerring rifle, before he discovered his mistake. But the legend, like that of Jessie Brown at Lucknow and many others in which we delight, has no foundation in fact, and so far as known there was no special romance connected with the marriage of Boone to the excellent lady who became his partner for life.

The children born of this marriage were James, Israel, Jesse, Daniel, Nathan, Susan, Jemima, Lavinia, and Rebecca.

CHAPTER II.

Social Disturbances in North Carolina—Eve of the American Revolution—Boone's Excursions to the West—Inscription on a Tree—Employed by Henderson and Company—The "Regulators" of North Carolina—Dispersed by Governor Tryon—John Finley—Resolution to go West.

The early part of Daniel Boone's married life was uneventful, and the years glided by without bringing any incident, event or experience to him worthy the pen of the historian. He toiled faithfully to support his growing family, and spent a goodly portion of his time in the woods, with his rifle and dog, sometimes camping on the bank of the lonely Yadkin, or floating down its smooth waters in the stillness of the delightful afternoon, or through the solemn quiet of the night, when nothing but the stars were to be seen twinkling overhead.

But Daniel Boone was living in stirring times, and there were signs in the political heavens of tremendous changes approaching. There was war between England and France; there was strife along the frontier, where the Indian fought fiercely against the advancing army of civilization, and the spirit of resistance to the tyranny of the mother country was growing rapidly among the sturdy colonists. North Carolina began, through her representatives in legislature, those measures of opposition to the authority of Great Britain, which forecast the active part the Old Pine Tree State was to take in the revolutionary struggle for liberty and independence.

During the few years that followed there was constant quarreling between the royal governor and the legislators, and it assumed such proportions that the State was kept in continual ferment. This unrest and disturbance were anything but pleasing to Boone, who saw the country settling rapidly around him, and who began to look toward the West with the longing which comes over the bird when it gazes yearningly out from the bars of its cage at the green fields, cool woods, and enchanting landscapes in which its companions are singing and reveling with delight.

Boone took long hunting excursions toward the West, though nothing is known with exact certainty as to the date when he began them. The Cherokee war which had caused much trouble along the Carolina frontier was ended, and he and others must have turned their thoughts many a time to the boundless forests which stretched for hundreds and thousands of miles towards the setting sun, in which roamed countless multitudes of wild animals and still wilder beings, who were ready to dispute every foot of advance made by the white settlers.

Such a vast field could not but possess an irresistible attraction to a consummate hunter like Boone, and the glimpses which the North Carolina woods gave of the possibilities awaiting him, and the growth of empire in the West, were sure to produce the result that came when he had been married some fifteen or more years and was in the prime of life.

Previous to this date, the well known abundance of game in Tennessee led many hunters to make incursions into the territory. They sometimes formed large companies, uniting for the prospect of gain and greater protection against the ever-present danger from Indians.

It is mentioned by good authority, that among the parties thus venturing over the Carolina border into the wilderness, was one at the head of which was "Daniel Boone from the Yadkin, in North Carolina, who traveled with them as low as the place where Abingdon now stands, and there left them."

Some years ago the following description could be deciphered upon an old beech-tree standing between Jonesboro and Blountsville:

CILLED A. BAR ON

IN THE TREE

YEAR 1760.

This inscription is generally considered as proof that Boone made hunting excursions to that region at that early date, though the evidence can hardly be accepted as positive on the point.

It was scarcely a year after the date named, however, that Boone, who was still living on the Yadkin, entered the same section of the country, having been sent thither by Henderson & Company for the purposes of exploration. He was accompanied by Samuel Callaway, a relative, and the ancestor of many of the Callaways of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Missouri. The latter was at the side of Boone when, approaching a spur of the Cumberland mountains, upon whose slopes they saw multitudes of bisons grazing, the great pioneer paused, and surveying the scene for a moment, exclaimed, with kindling eyes:

"I am richer than He who owned the cattle on a thousand hills, for I own the wild beasts of a thousand valleys."

The sight was indeed one which might have stirred the heart of a hunter who could grasp the possibilities of the future of those favored regions.

Daniel Boone may be considered as having undergone a preliminary training from his earliest boyhood for the work which has identified his name indissolubly with the history of Kentucky. He was what may be called a born pioneer, but there were causes at work in North Carolina which led to his departure for the Kentucky wilderness, of which the general reader is apt to lose sight in studying his character.

The approach of the American Revolution in the former State, as in many others, was marked by social disturbances frequently amounting to anarchy. There were many Scotch traders, who had accumulated considerable wealth without having gone through the labor and perils which the natives underwent in providing for their families.

These foreigners adopted an expensive and showy style of living, altogether out of keeping with the severe simplicity that marked that of the colonists.

Nothing was more natural than that this assumption of superiority in the way of social position should roil and excite resentment among those less favored by fortune.

They were not alone in this offensive course: the officers and agents of the Royal Government were equally ostentatious in display and manner of living, and the exasperating snobbishness spread to the magistrates, lawyers, clerks of court, and tax gatherers, who demanded exorbitant fees for their services. The clergymen of the Established Church became oppressive in their exactions, and, as we have stated, society itself was threatened with revolution before the rattle of musketry at Bunker Hill "was heard around the world."

Petitions were sent to the Legislature for relief by the suffering citizens, who were in much the same distressing situation in which Ireland has been many a time since. These prayers were treated with indifference or open contempt, for there are none more reckless and blind than those who are traveling close to the edge of the political volcano rumbling at their feet.

There is a limit beyond which it is always dangerous to tempt the endurance of a people, who now began meeting together, and formed themselves into associations for correcting the evils around them. It was these people who received the name of "Regulators," and who helped to increase the disturbances in that particular section of the country. They deliberately decided "to pay only such taxes as were agreeable to law, and applied to the purpose therein named, and to pay no officer more than his legal fees."

The history of the State records many acts of violence which were inevitable from this condition of affairs. The final collision between the "Regulators" and a strong force of the royal governor Tryon at Alamanance, in which the rebels were badly defeated, occurred in May, 1771, but the disturbances continued with more or less violence until the breaking out of the Revolution, when the mills of God ground so "exceeding fine," that the grievances were removed forever.

It was in such a community as this that Daniel Boone lived, and he and his family were sufferers. What more natural than that he should cast his eyes longingly toward the West, where, though there might be wild beasts and wild men, he and his loved ones could be free from the exasperating annoyances which were all around them?

The perils from Indians were much less alarming to them than were those of the tax-gatherer. Indeed, in all probability, it lent an additional attractiveness to the vast expanse of virgin wilderness, with its splashing streams, its rich soil, its abundance of game and all that is so enchanting to the real sportsman, who finds an additional charm in the knowledge that the pleasure upon which he proposes to enter is spiced with personal danger.

One day a visitor dropped in upon Boone. He was John Finley, who led a party of hunters to the region adjoining the Louisa River in Kentucky in the winter of 1767, where they spent the season in hunting and trapping. The hunter called upon Boone to tell him about that land in which he knew his friend was so much interested.

We can imagine the young man, with his rifle suspended on the deer-prongs over the fire, with his wife busy about her household duties and his children at play, sitting in his cabin and listening to the glowing narrative of one who knew whereof he was speaking.

Finley told him of the innumerable game, the deer and bison, the myriads of wild turkeys, and everything so highly prized by the sportsman; he pictured the vast stretches of forest in which the hunter could wander for hours and days without striking a clearing; of the numerous streams, some large, some small, and all lovely to the eye, and it needed no very far-seeing vision to forecast the magnificent future which lay before this highly favored region.

It must have been a winsome picture drawn by Finley—aided as it was by the repelling coloring of the scene of his actual surroundings—made so hateful by the oppressive agents of the foreign government which claimed the colonies as her own.

When Finley was through, and he had answered all of his friend's questions, and told him of his many hunting adventures in Kentucky, Boone announced that he would go with him when he should make his next visit. He had already been drawn strongly toward the region, and he wished to see with his own eyes the favored land, before removing his family thither.

The acquisition of such a person was so desirable, that he was sure to be appreciated by those who knew him best, and whether appointed to that position or not, his own matchless resources and natural powers were certain to fix upon him as the leader of the adventurous characters who had decided to explore the dangerous wilderness of Kentucky.

CHAPTER III.

The Party of Exploration—Daniel Boone the Leader—More than a Month on the Journey—On the Border of Kentucky—An Enchanting View—A Site for the Camp—Unsurpassed Hunting—An Impressive Solitude—No Signs of Indians.

Daniel Boone now entered upon that epoch in his life, which has interwoven his name with the history of Kentucky, and indeed with the settlement of the West, for though he was not venturing into the wilderness with the intention of remaining there, yet his purpose of "spying out the land" was simply the first step in his career of pioneer of the Dark and Bloody Ground.

The party of exploration, or rather of hunting, numbered a half dozen: John Finley, James Moncey, John Stuart, William Cool, Joseph Holden, and Daniel Boone, who was chosen the leader. It was a strong company, for all the men were experienced hunters, unerring rifle-shots, and well aware of the dangers they were to encounter.

On the first of May, 1769, the party set out for Kentucky in high spirits, and eagerly anticipating the enjoyment that was to be theirs, before they should return from the all-important expedition.

They had selected the most enchanting season of the year, and it is easy to imagine with what glowing anticipation they ventured upon the journey, which was to be more eventful, indeed, than any member of it imagined.

It was a long distance from North Carolina, across the intervening stretch of stream, forest and mountain, to Kentucky, with all the temptations to the hunter to turn aside, temptations which it is safe to conclude overcame them many a time, for, when a full month had passed, not one of the party had stepped within the confines of the Dark and Bloody Ground.

But, though they were moving slowly, they were steadily nearing the promised land, and on the 7th of June the men, bronzed and toughened by the exposure to which they had been subjected, but still sturdy and resolute, began climbing the precipitous slope of a mountain on the border of Kentucky.

The six who had left North Carolina more than a month before were there, attired in their rough hunting costume, and with their ambition and purpose as strong as ever. Each wore the hunting-shirt of the forest ranger made of dressed deerskins. The leggins were of the same material, and the feet were protected by strong, comfortably fitting moccasins. There were fringes down the seams of the leggins, just as seems to be the favorite custom with many of the red-men in donning their picturesque costumes.

Although these dresses might be attractive to the eye, yet such a purpose was the last that entered the minds of the wearers, who constructed them for use only. Their under garments were of cotton, so coarse that it would have been like sackcloth to many a man of modern days; they carried, as a matter of course, the powder-horn, rifle, hatchet, bullet-pouch, and the other indispensables of a hunter.

It was near the close of the day, and though the party were pretty well exhausted, yet they pushed on, feeling in many respects like those who, for the first time in their lives, are to gaze upon the land which is more enchanting to them than all the world beside.

Ere the sun sank behind the immense expanse of wilderness, and just when its splendors were illuminating the skies with the glories of the fading day, the hunting party reached the summit of the mountain, and gazed off over Kentucky.

The panorama spread out before them was a most entrancing one, their vision extending over hundreds of square miles, with the rich vales watered by the beautiful streams, the forest alternating with broad natural clearings, with vast stretches of level country upon which the myriads of moving specks were recognized by the experienced eye as bisons, and over which they knew the deer dashed and other wild animals roamed with scarcely a fear of their natural enemy, man. There was many a league in whose solemn depths a human foot had never yet penetrated, and whose echoes had never been awakened by the shot of the rifle. There they lay as silent as at "creation's morn," and the denizens of the woods waxed strong and wandered at will, without fear of the deadly bullet whistling from behind the tree or mossy rock.

True, among these cool woods and within many of the dark recesses the red Indian ventured, and now and then the sharp whiz of his arrow was heard, and the barbed weapon flashed among the green leaves as it pierced the heart of the unsuspecting natives of the wood.

But where there were such multitudes of wild beasts these deaths were scarcely noticeable, and the white hunters knew that it was a sportsman's paradise that lay spread at their feet.

The picture of these six pioneers who paused on the crest of the mountain as the sun was setting, and looked off over the Kentucky wilderness, is that which has been selected by the artist, who has immortalized the scene on canvas, and all will agree that he could not have chosen a more inviting subject.

The surface upon which they looked down was rolling, level far beyond, but quite hilly nearer the base of the mountain, while it all possessed the indescribable charm of variety, and it could not have been more enchanting to the wearied spectators.

Finley had been there before, and, though they may have thought that some of the stories he told were overdrawn, they could well afford to believe them now, when they came to gaze upon the attractive country.

Aye, they stood on the very borders of the land, and they determined that they would venture within it on the morrow. Although they had left home at the most delightful season of the year, yet the spring proved to be a severe one, and their journey had been delayed by stormy weather, so that the glowing panorama at their feet was robed in more roseate colors from its very contrast to that through which they had passed so recently.

Assuming positions of rest, the group feasted their eyes to the full, and we can well imagine the expressions of delight which escaped them, as they constantly caught sight of new and novel scenes and pointed them out to each other.

There lay the region in which they would probably make their future home, whither they would bring their families, and where they would encounter the toil, privation and danger, which invariably attend the pioneers of every country.

Under such circumstances, the time, place and surroundings were invested with a peculiar interest, which could not have been theirs at any other period or under any different conditions.

The sun went down behind the wilderness, and night gradually overspread the scene. The hunters had not caught sight of a single human being beside themselves, and now that darkness had come, they made their preparations to encamp for the night.

They were veterans at this business, as they showed by avoiding such a conspicuous position as they then occupied. The flash of a camp-fire on the mountain-top would have been seen for many miles over the wilderness, and though they had discovered nothing of the red-men, yet it was reasonable to suppose that many of them would look out from the dark recesses at the unwonted spectacle and would suspect the true cause.

And so, from a prudent habit they had formed, they moved down to a neighboring ravine, where they camped for the night.

The spot was favorable in every respect, the gorge being so deep, and surrounded by such a dense thicket, that the glimmer of the camp-fire was not likely to be seen by any one, unless he ventured close enough to hear the murmur of the voices of the hunters as they gathered together for their evening meal.

Near them lay a tree that had been uprooted by some recent storm, and which offered the advantages the hunters could not fail to appreciate at sight. The huge trunk was used for the rear wall of the camp, as it may be termed, while logs and brush were gathered and piled on two sides, leaving the front open, where the fire was kindled against another log. Thus they were secured against any chill during the cold night, while no wild animal was likely to venture across the magic ring of fire, in case he was attracted to the spot.

It was decided not only to make this their resting-place for the night, but their headquarters during their visit to Kentucky.

Accordingly, their camp was strengthened, as may be said, a roof being made more substantial than ornamental, but sufficient to keep out the rain, and the front was narrowed in, so that no matter how sudden or violent the changes of weather, they were well protected against them.

Their greatest safeguard, however, lay in their own hardy constitutions and rugged health, which they had acquired from their active out-door life long before venturing into this wild region.

This visit to Kentucky was extended all through the summer and autumn until the dead of winter, during which time they made the camp in the gorge their headquarters.

They had many a glorious hunt, as may well be supposed, and it would be unsafe to estimate the numbers of bisons, deer, wild turkeys, bear and other species of game that fell victims to the unerring marksmen. It is unnecessary to say that they lived like princes, and grew stronger, sturdier, and more hopeful. Although separated from their families to which they were tenderly attached, there was an indescribable charm about this wild out-door life that rendered the social annoyances to which they were subjected at home all the more distasteful.

They felt that if a band of worthy colonists could be gathered, and a venture made into Kentucky, the future was sure to be all they could wish.

Beyond question, this preliminary visit to Kentucky settled the future not only of Boone himself, but of others who were associated with him.

It seems an extraordinary statement to make, and yet it is a fact that, during that entire summer and autumn and a goodly portion of the winter which they spent there, they never once saw an Indian—the very enemy which it was to be supposed they would alone dread, and who would be the most certain to molest them.

When it is remembered that the Indians had made so much trouble on the Carolina frontiers, this is all the more remarkable, until we recollect that Kentucky at that day, and for years after, was regarded by the red-men as a sort of neutral hunting ground, no particular tribe laying claim to it. But it was territory into which each possessed an equal right to venture and wage deadly hand-to-hand encounters—while all united with an undying enmity to drive back any white man who presumed to step foot upon the Dark and Bloody Ground. It must have been, too, that the Indians scattered through the region were not expecting any visitors.

Kentucky at that time belonged to the colony of Virginia. The Shawanoes, Cherokees, and Chickasaws frequently ventured into the region to hunt, but the Iroquois had ceded all their claim to the grounds to Great Britain at Fort Stanwix, in 1768, so that it will be understood that Boone and his companions were not venturing into Indian territory at all, though it is not to be supposed that any estray red-men whom they might encounter in their hunts would be likely to regard the exact status of the matter.

The hunters preferred not to encounter them at all, but were cautious in their movements, and "put their trust in God and kept their powder dry."

Accordingly, as we have stated, they prosecuted their hunting through the sultry summer months, alternating with storm and sunshine, and enjoying themselves to the fullest bent of which such spirits are capable.

Autumn came, cool and invigorating, and winter with its biting winds and piercing cold followed, making the primitive cabin in the mountain gorge a most inviting spot in which to spend their leisure hours. They smoked their pipes after the evening meal, and held friendly converse as the hours wore on, when they stretched out and slept through the solemn stillness, broken now and then by the mournful cry of some wild animal, until morning again dawned.

Many of the excursions which they made had led them far into the interior, and, as may be supposed, they kept their eyes and ears open.

They had not only failed to meet an Indian, but failed to catch sight of a wigwam, or the smoke of a camp-fire other than their own; so that, as we have repeated, they were justified, if any one could have been, in believing that the last peril to which they were likely to be exposed, was that from red-men.

And yet it was precisely that danger which was impending over them, and which descended when it was least expected.

CHAPTER IV.

Boone and Stuart start out on a Hunt—Captured by Indians and Disarmed—Stuart's Despair and Boone's Hope—A Week's Captivity—The Eventful Night.

On the morning of December 22, 1769, Daniel Boone and his friend John Stuart left camp, and started out on a hunt.

It was the shortest day in the year, so it is to be supposed that they were desirous of improving it to the utmost, although they had become so accustomed to such excursions, that there was no special expectation excited by their venturing forth together for a hunt through the woods.

Experienced as they were in woodcraft, they saw nothing to cause the slightest misgivings. Their keen eyes, as they roamed around the horizon, detected no faint wreath of smoke stealing upward through the tree-tops, telling where the camp of the treacherous Shawanoe was kindled; the listening ear detected no skillfully disguised bird-call trembling on the crisp air to warn them of the wily red-man skulking through the cane, and waiting until they should come within reach of their bow or rifle.

After leaving camp, the friends followed one of the numerous "buffalo paths" through the cane, and in a few minutes were out of sight of their comrades left behind. The air was keen and invigorating, and they traveled carelessly along, admiring the splendid growth of the timber and cane, showing what an unsurpassed soil awaited the pioneers who should settle in these valleys, and turn up the sod for the seed of the harvest.

Where the game was so plentiful, there was no likelihood of the hunters suffering from lack of food. The buffaloes were so numerous that they were able to approach the droves close enough to reach them with the toss of a stone.

Stuart and Boone enjoyed themselves, as they had done on many a day before, until the declining sun warned them that it was time to turn their faces toward camp, if they expected to spend the night with their friends in the rude but comfortable cabin.

They did so, and the sun had not yet gone down behind the line of western forest, when they reached a small hill near the Kentucky River, and began leisurely moving to the top.

It was at this juncture, that a party of Indians suddenly sprang up from the canebrake and rushed upon them with such fierceness that escape was out of the question. It was not often that Daniel Boone was caught at disadvantage, but in this instance he was totally outwitted, and it looked for the moment as if he and his companion had walked directly into a trap set for them.

The pioneers were too prudent to attempt anything in the nature of resistance when the result could but be their almost instant death, for the Indians outnumbered them five to one, were fleet as deer, and understood all the turnings and windings of the forest. Accordingly, Boone and Stuart quietly surrendered, hoping for the best, but expecting the worst.

As might be supposed, the Indians disarmed the hunters, and made them prisoners at once. Stuart was terribly alarmed, for he could not see the slightest ground for hope, but Boone, who possessed a most equable temperament, told him to keep up heart.

"As they haven't killed us," said the pioneer, "it shows they intend to spare us for a time, at least."

"Only to torture us to death hereafter," thought his terrified companion.

"I don't doubt that such are their intentions, but between now and the time, we may find our chance. Be obedient and watchful—doing nothing to provoke them, but be ready when the right minute comes."

This was good advice, and Stuart was sensible enough to follow it in spirit and letter.

It might have been expected that if a couple of hunters intended to strike a blow for liberty, they would do so pretty soon after their capture—that is, as soon as the darkness of night was in their favor—but it was only characteristic of Boone that a full week passed before he made the first attempt to escape.

During those seven days they could not fail to catch glimpses, as it were, of freedom, and to be tempted to make a desperate dash, for many a time it is the very boldness of such efforts that succeeds.

But Boone never lost his prudence of mind, which enabled him to abide his time. Stuart, too, acted as he suggested, and they very effectually concealed their eagerness to escape.

However, it was not to be expected that the Indians would be careless enough to allow them to get away, and they maintained a most vigilant watch upon them at all hours of the day and night. When tramping through the wilderness or in camp, when hunting, or sitting around the smoking logs, the suspicious red-men were near them. When the hour came to sleep, the prisoners were placed so as to be surrounded, while a strong and vigilant guard was appointed to watch over them until daylight.

Boone and Stuart affected quite successfully an indifference to their situation, and, inasmuch as they had not sought to take advantage of what might have been intended as traps in the way of opportunities to get away, it was only natural for the captors to conclude that the white men were willing to spend an indefinite time with them.

What the ultimate intentions of these Indians were, can only be conjectured, for they were a long distance from their lodges, but those who ventured upon hunting excursions within the Dark and Bloody Ground were of the fiercest nature, and as merciless as Bengal tigers, as they proved in many a desperate encounter with the settlers; and it is no more than reasonable to suppose that they meant in the end to burn them at the stake, while they danced about the scene with fiendish glee, just as they did a few years later with Colonel Crawford and other prisoners who fell into their hands.

At last the week ended, and at the close of the seventh day, the Indians encamped in a thick canebrake. They had been hunting since morning, and no opportunity presented that satisfied Boone, but he thought the time was close at hand when their fate was to be decided.

The long-continued indifference as shown by him and his companion had produced its natural effect upon the Indians, who showed less vigilance than at first.

But they knew better than to invite anything like that which was really contemplated, and, when the night was advanced, the majority of the warriors stretched out upon the ground in their blankets, with their feet toward the fire.

It had been a severe day with all of them, and the watchful Boone noticed that the guard appointed over him and his companion were drowsy and inattentive, while maintaining a semblance of performing their duty.

"It must be done to-night," was the conclusion of the pioneer, who was sure the signs were not likely to be more propitious.

He lay down and pretended slumber, but did not sleep a wink: his thoughts were fixed too intently upon the all-important step he had resolved must be taken then or never, and he lay thus, stretched out at full length before the hostile camp-fire, patiently awaiting the critical moment.

CHAPTER V.

The Escape—The Hunters find the Camp Deserted—Change of Quarters—Boone and Kenton—Welcome Visitors—News from Home—In Union there is Strength—Death of Stuart—Squire Boone returns to North Carolina for Ammunition—Alone in the Wilderness—Danger on Every Hand—Rejoined by his Brother—Hunting along the Cumberland River—Homeward Bound—Arrival in North Carolina—Anarchy and Distress—Boone remains there Two Years—Attention directed towards Kentucky—George Washington—Boone prepared to move Westward.

It was near midnight when, having satisfied himself that every warrior, including the guard, was sound asleep, Boone cautiously raised his head and looked towards Stuart.

But he was as sound asleep as the Indians themselves, and it was a difficult and dangerous matter to awaken him, for the Indian sleeps as lightly as the watching lioness. The slightest incautious movement or muttering on the part of the man would be sure to rouse their captors.

But Boone managed to tell his companion the situation, and the two with infinite care and caution succeeded in gradually extricating themselves from the ring of drowsy warriors.

"Make not the slightest noise," whispered Boone, placing his mouth close to the ear of Stuart, who scarcely needed the caution.

The camp-fire had sunk low, and the dim light thrown out by the smouldering logs cast grotesque shadows of the two crouching figures as they moved off with the noiselessness of phantoms. Having gained such immense advantage at the very beginning, neither was the one to throw it away, and Stuart followed the instructions of his companion to the letter.

The forms of the Indians in their picturesque positions remained motionless, and it need hardly be said that at the end of a few minutes, which seemed ten times longer than they were, the two pioneers were outside the camp, and stood together beneath the dense shadows of the trees.

It was a clear, starlit night, and the hunters used the twinkling orbs and the barks of the trees to guide them in determining the direction of their camp, towards which they pushed to the utmost, for having been gone so long, they were naturally anxious to learn how their friends had fared while they were away.

Boone and Stuart scarcely halted during the darkness, and when the sun rose, were in a portion of the country which they easily recognized as at no great distance from the gorge in which they had erected their cabin more than six months before.

They pressed on with renewed energy, and a few hours later reached the camp, which to their astonishment they found deserted. The supposition was that the hunters had grown tired or homesick and had gone home, though there is no certainty as to whether they were not all slain by the Indians, who seem to have roused themselves to the danger from the encroachments of the whites upon their hunting-grounds.

It was a great disappointment to Boone and Stuart to find themselves alone, but they determined to stay where they were some time longer, even though their supply of ammunition was running low, and both were anxious to hear from home.

The certainty that the Indians were in the section about them, as the friends had learned from dear experience, rendered it necessary to exercise the utmost caution, for, if they should fall into their hands again, they could not hope for such a fortunate deliverance.

Instead of using the headquarters established so long before, they moved about, selecting the most secret places so as to avoid discovery, while they were constantly on the alert through the day.

But both were masters of woodcraft, and Boone probably had no superior in the lore of the woods. It is said of him that, some years later, he and the great Simon Kenton reached a river from opposite directions at the same moment, and simultaneously discovered, when about to cross, that a stranger was on the other side.

Neither could know of a certainty whether he confronted a friend or enemy, though the supposition was that he was hostile, in which event the slightest advantage gained by one was certain to be fatal to the other.

Immediately the two hunters began maneuvering, like a couple of sparrers, to discover an unguarded point which would betray the truth. It was early morning when this extraordinary duel opened, and it was kept steadily up the entire day. Just at nightfall the two intimate friends succeeded in identifying each other.

A man with such Esquimau-like patience, and such marvelous ingenuity and skill, was sure to take the best care of himself, and during the few days of hunting which followed, he and Stuart kept clear of all "entangling alliances," and did not exchange a hostile shot with the red-men.

In the month of January, they were hunting in the woods, when they caught sight of two hunters in the distance among the trees. Boone called out:

"Hallo, strangers! who are you?"

"White men and friends," was the astonishing answer.

The parties now hastened towards each other, and what was the amazement and happiness of the pioneers to find that one of the men was Squire Boone, the younger brother of Daniel, accompanied by a neighbor from his home on the far-off Yadkin.

They had set out to learn the fate of the hunting party that left North Carolina early in the spring, and that had now been so long absent that their friends feared the worst, and had sent the two to learn what had become of them, just as in these later days we send an expedition to discover the North Pole, and then wait a little while and send another to discover the expedition.

No one could have been more welcome to the two pioneers, for they brought not only a plentiful supply of ammunition, but, what was best of all, full tidings of the dear ones at home.

Squire Boone and his companion had found the last encampment of their friends the night before, so they were expecting to meet them, though not entirely relieved of their anxiety until they saw each other.

It can be imagined with what delight the four men gathered around their carefully guarded camp-fire that evening, and talked of home and friends, and listened to and told the news and gossip of the neighborhood, where all their most loving associations clustered. It must have been a late hour when they lay down to sleep, and Daniel Boone and Stuart that night could not fail to dream of their friends on the banks of the distant Yadkin.

The strength of the party was doubled, for there were now four skillful hunters, and they had plenty of ammunition, so it was decided to stay where they were some months longer.

It seems strange that they should not have acted upon the principle that in union there is strength, for instead of hunting together, they divided in couples. This may have offered better prospects in the way of securing game, but it exposed them to greater danger, and a frightful tragedy soon resulted.

Boone and Stuart were hunting in company, when they were suddenly fired into by a party of Indians, and Stuart dropped dead. Boone was not struck, and he dashed like a deer into the forest. Casting one terrified glance over his shoulder, he saw poor Stuart scalped as soon as he fell to the earth, pierced through the heart by the fatal bullet.

This left but three of them, and that fearfully small number was soon reduced to two. The hunter who came from North Carolina with Squire Boone was lost in the woods, and did not return to camp. The brothers made a long and careful search, signaling and using every means possible to find him, but there was no response, and despairing and sorrowful they were obliged to give over the hunt. He was never seen again. Years afterward the discovery of a skeleton in the woods was believed to indicate his fate. It is more than probable that the stealthy shot of some treacherous Indian, hidden in the canebrake, had closed the career of the man as that of Stuart was ended.

The subsequent action of Boone was as characteristic as it was remarkable. It is hard to imagine a person, placed in the situation of the two, who would not have made all haste to return to his home; and this would be expected, especially, of the elder brother, who had been absent fully six months longer than the other.

And yet he did exactly the opposite. He had fallen in love with the enchantments of the great Kentucky wilderness, with its streams, rivers and rich soil, and its boundless game, and he concluded to stay where he was, while Squire made the long journey back to North Carolina for more ammunition.

Daniel reasoned that when Squire rejoined his family and acquainted them with his own safety, and assured the wife and children that all was going well with him, the great load of anxiety would be lifted from their minds, and they would be content to allow the two to make a still more extended acquaintance with the peerless land beyond the Cumberland mountains.

Accordingly Squire set out for his home, and it should be borne in mind that his journey was attended by as much danger as was the residence of the elder brother in Kentucky, for he was in peril from Indians all the way.

Daniel Boone was now left entirely alone in the vast forests, with game, wild beasts and ferocious Indians, while his only friend and relative was daily increasing the distance between them, as he journeyed toward the East.

Imagination must be left to picture the life of this comparatively young man during the three months of his brother's absence. Boone was attached to his family, and yet he chose deliberately to stay where he was, rather than accompany his brother on his visit to his home.

But he had little time to spend in gloomy retrospection or apprehensions, for there were plenty of Indians in the woods, and they were continually looking for him.

He changed his camp frequently, and more than once when he lay hidden in the thick cane and crawled stealthily back to where he had spent the previous night, the print of moccasins in the earth told him how hot the hunt had been for him.

Indian trails were all about him, and many a time the warriors attempted to track him through the forest and canebrakes, but the lithe, active pioneer was as thorough a master of woodcraft as they, and he kept out of their way with as much skill as Tecumseh himself ever showed in eluding those who thirsted for his life.

He read the signs with the same unerring accuracy he showed in bringing down the wild turkey, or in barking the squirrel on the topmost limb. Often he lay in the canebrake, and heard the signals of the Indians as they pushed their search for the white man who, as may be said, dared to defy them on their own ground.

Boone could tell from these carefully guarded calls how dangerous the hunt was becoming, and when he thought the warriors were getting too close to his hiding-place, he carefully stole out and located somewhere else until perhaps the peril passed.

There must have been times when, stretched beneath the trees and looking up at the twinkling stars, with the murmur of the distant river or the soughing of the night-wind through the branches, his thoughts wandered over the hundreds of miles of intervening wilderness to the humble home on the bank of the Yadkin, where the loved wife and little ones looked longingly toward the western sun and wondered when the husband and father would come back to them.

And yet Boone has said, while admitting these gloomy moments, when he was weighed down by the deepest depression, that some of the most enjoyable hours of his life were those spent in solitude, without a human being, excepting a deadly enemy, within hail.

The perils which followed every step under the arches of the trees, but rendered them the more attractive, and the pioneer determined to remove his family, and to make their home in the sylvan land of enchantment just so soon as he could complete the necessary arrangements for doing so.

On the 27th of July, 1770, Squire Boone returned and rejoined his brother, who was glad beyond description to receive him, and to hear so directly from his beloved home. During the absence of the younger, the other had explored pretty much all of the central portion of Kentucky, and the result was that he formed a greater attachment than ever for the new territory.

When Squire came back, Daniel said that he deemed it imprudent to stay where they were any longer. The Indians were so numerous and vigilant that it seemed impossible to keep out of their way; accordingly they proceeded to the Cumberland River, where they spent the time in hunting and exploration until the early spring of 1771.

They gave names to numerous streams, and, having enjoyed a most extraordinary hunting jaunt, were now ready to go back to North Carolina and rejoin their families.

But they set out for their homes with not the slightest purpose of staying there. They had seen too much of the pleasures of the wood, for either to be willing to give them up. In North Carolina there was the most exasperating trouble. The tax-gatherer was omnipresent and unbearably oppressive; the social lines between the different classes was drawn as if with a two-edged sword; there were murmurs and mutterings of anger in every quarter; Governor Tryon, instead of pacifying, was only fanning the flames; ominous signs were in the skies, and anarchy, red war and appalling disaster seemed to loom up in the near future.

What wonder, therefore, that Daniel Boone turned his eyes with a longing such as comes over the weary traveler who, after climbing a precipitous mountain, looks beyond and sees the smiling verdure of the promised land.

He had determined to emigrate long before, and he now made what might be called the first move in that direction. He and his brother pushed steadily forward without any incident worth noting, and reached their homes in North Carolina, where, as may well be supposed, they were welcomed like those who had risen from the dead. They had been gone many months, and in the case of Daniel, two years had passed since he clasped his loved wife and children in his arms.

The neighbors, too, had feared the worst, despite the return of Squire Boone with the good news of the pioneer, and they were entertained as were those at court when Columbus, coming back from his first voyage across the unknown seas, related his marvelous stories of the new world beyond.

Daniel Boone found his family well, and, as his mind was fixed upon his future course, he began his preparations for removal to Kentucky.

This was a most important matter, for there was a great deal to do before the removal could be effected. It was necessary to dispose of the little place upon which they had lived so long and bestowed so much labor, and his wife could not be expected to feel enthusiastic over the prospect of burying herself in the wilderness, beyond all thought of returning to her native State.

Then again Boone was not the one to entertain such a rash scheme as that of removing to Kentucky, without taking with him a strong company, able to hold its own against the Indians, who were certain to dispute their progress.

It is easy to understand the work which lay before Boone, and it may be well believed that months passed without any start being made, though the great pioneer never faltered or wavered in his purpose.

Matters were not improving about him. The trouble, distress, and difficulties between the authorities and the people were continually aggravated, and the Revolution was close at hand.

At the end of two years, however, Boone was prepared to make the momentous move, and it was done. The farm on the Yadkin was sold, and he had gathered together a goodly company for the purpose of forming the first real settlement in Kentucky.

During the few years immediately preceding, the territory was visited by other hunters, while Boone himself was alone in the solitude. A company numbering forty, and led by Colonel James Knox, gathered for a grand buffalo hunt in the valleys of the Clinch, New River, and Holston. A number of them skirted along the borders of Tennessee and Kentucky.

While they were thus engaged, others penetrated the valleys from Virginia and Pennsylvania, and among them was a young man named George Washington.

As is well known, his attention had been directed some time before to the lands along the Ohio, and he owned a number of large claims. He clearly foresaw the teeming future of the vast West, and he was especially desirous of informing himself concerning the lands lying in the neighborhood of the mouth of the Kanawha.

At that particular date, the Virginians were converging toward the country south of the river, and there were many difficulties with the Indians, who then as now are ready to resist entrance upon their hunting-grounds, even though the immigrants are backed by the stipulations of a recently signed treaty.

CHAPTER VI.

Leaving North Carolina—Joined by a Large Company at Powell's Valley—Glowing Anticipations—Attacked by Indians in Cumberland Gap—Daniel Boone's Eldest Son Killed—Discouragement—Return to Clinch River Settlement—The Check Providential—Boone acts as a Guide to a Party of Surveyors—Commissioned Captain by Governor Dunmore, and takes command of Three Garrisons—Battle of Point Pleasant—Attends the making of a Treaty with the Indians at Wataga—Employed by Colonel Richard Henderson—Kentucky claimed by the Cherokees—James Harrod—The First Settlement in Kentucky—Boone leads a Company into Kentucky—Attacked by Indians—Erection of the Fort at Boonesborough—Colonel Richard Henderson takes Possession of Kentucky—The Republic of Transylvania—His Scheme receives its Death-blow—Perils of the Frontier—A Permanent Settlement made on Kentucky Soil.

On the 25th of September, 1774, Daniel Boone and his family started to make their settlement in Kentucky.

He had as his company his brother Squire, who had spent several months with him in the wilderness, and they took with them quite a number of cattle and swine with which to stock their farms when they should reach their destination, while their luggage was carried on pack-horses.

At Powell's Valley, not very far distant, they were joined by another party, numbering five families and forty able-bodied men, all armed and provided with plenty of ammunition. This made the force a formidable one, and they pushed on in high spirits.

When night came they improvised tents with poles and their blankets, and the abundance of game around them removed all danger of suffering from the lack of food, for it was but sport to bring down enough of it to keep the entire company well supplied.

The experience of the Boones, when they passed through this region previously, taught them to be on their guard constantly, for the most likely time for the Indians to come is when they are least expected, and the leaders saw to it that no precaution was neglected.

And yet it is easy to see that such a large company, moving slowly, and encumbered by women and children and so much luggage and live-stock, was peculiarly exposed to danger from the dreaded Indians.

On the 10th of October they approached Cumberland Gap. The cattle had fallen to the rear, where they were plodding leisurely along, with several miles separating them from their friends in front, when the latter suddenly heard the reports of guns coming to them through the woods. They instantly paused and, looking in each other's pale faces, listened.

There could be no mistaking their meaning, for the reports were from the direction of the cattle in the rear, and the shouts and whoops came from the brazen throats of Indians, who had attacked the weak guard of the live-stock.

Boone and his friends, leaving a sufficient guard for the women and children, hurried back to the assistance of the young men, who were in such imminent peril.

There was sore need of their help indeed, for the attack, like the generality of those made by Indians, was sudden, unexpected, and of deadly fierceness. When the panting hunters reached the spot, they found the cattle had been stampeded and scattered irrecoverably in the woods, while of the seven men who had the kine in charge, only one escaped alive, and he was badly wounded.

Among the six who lay stretched in death, was the oldest son of Daniel Boone, slain, as may be said, just as he was about entering upon the promised land.

The disaster was an appalling one, and it spread gloom and sorrow among the emigrants, who might well ask themselves whether, if they were forced to run the gauntlet in that fearful fashion, they would be able to hold their own if spared to reach Kentucky?

A council was called, and the question was discussed most seriously. Daniel Boone, who had suffered such an affliction in the loss of his child, strenuously favored pushing on, as did his brother and a number of the other emigrants, but the majority were disheartened by the disaster, and insisted on going back to their homes, where, though the annoyances might be many, no such calamity was to be dreaded.

The sentiment for return was so strong that the Boones were compelled to yield, and turning about, they made their way slowly and sadly to Clinch River settlement, in the southwestern part of Virginia, a distance of perhaps forty miles from where they were attacked by Indians.

It would be difficult to look upon this occurrence in any other light than a most serious check and misfortune, as certainly was the case, so far as the loss of the half dozen men was concerned, but the turning back of the rest of the party was unquestionably a providential thing.

It was a short time previous to this, that the historical Logan episode took place. The family of that noted chief and orator were massacred, and the fierce Dunmore War was the consequence. This was impending at the very time Boone and the others were journeying toward Kentucky, and breaking out shortly afterwards, extended to the very section in which the emigrants expected to settle, and where in all probability they would have suffered much more severely had they not turned back for the time.

Nothing could change the purpose of Boone to enter into Kentucky, and to make his home there. Although obliged from the sentiment of his friends to withdraw for a time, he looked upon the check as only a temporary one, and was confident that before long he would be firmly fixed in what he called the "land of promise."

Boone was not to be an idle spectator of the famous Dunmore War going on around him. In the month of June, 1774, he and Michael Stoner were requested by Governor Dunmore of Virginia to go to the falls of the Ohio, for the purpose of guiding into the settlement a party of surveyors, sent out some months before.

Boone and his friend promptly complied, and conducted the surveyors through the difficult and dangerous section without accident, completing a tour of eight hundred miles in a couple of months.

Shortly afterward Boone rejoined his family on Clinch river, and was there when Governor Dunmore sent him a commission as captain, and ordered him to take command of three contiguous garrisons on the frontier, during the prosecution of the war against the Indians.