Five Thousand Pounds

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

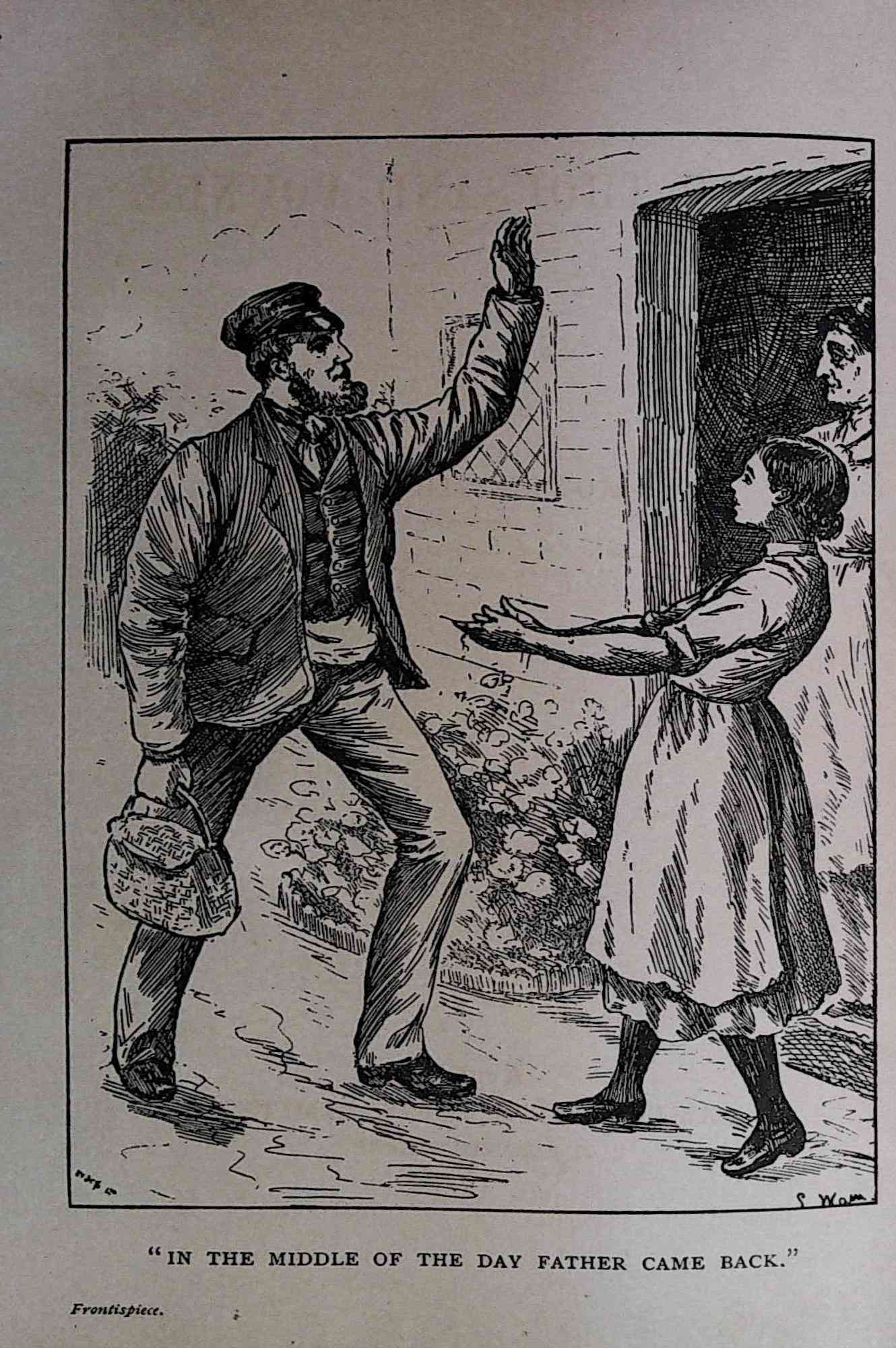

IN THE MIDDLE OF THE DAY FATHER CAME BACK.

FIVE THOUSAND POUNDS.

BY

AGNES GIBERNE,

AUTHOR OF

"ENID'S SILVER BOND;" "ST. AUSTIN'S LODGE;" "OLD UMBRELLAS;"

"BERYL AND PEARL;" ETC.

London

JAMES NISBET & CO., LIMITED

21 BERNERS STREET

Printed by BALLANTYNE, HANSON & CO.

At the Ballantyne Press

CONTENTS.

CHAP.

I. MY COTTAGE HOME

II. NEWS

III. THE MONEY

IV. CONGRATULATIONS

V. FIRST PURCHASES

VI. AN ALARM

VII. TO GO OR TO STAY

VIII. THE NEW HOUSE

IX. NOTHING TO DO

X. MR. SIMMONS

XI. GOING HOME

XII. AT LAST

XIII. A DAMP DWELLING

XIV. CHRISTMAS

XV. TROUBLE

XVI. SCENES

XVII. THE END

FIVE THOUSAND POUNDS.

CHAPTER I.

MY COTTAGE HOME.

UP to the age of fourteen I think I spent as happy a life as any child in any cottage home in England. There is many a cottage which is no "home" at all, in the true sense of the word, notwithstanding those pretty words of poetry about—

but ours was one.

It stood on a bit of country road, with three or four other cottages, close outside a biggish town. We had a large pond in front, and lots of trees beyond and on both sides of the pond; and the shadows of the trees used to look very pretty on a summer evening, when the light from the sun came creeping through them with a red glow like firelight. The water would catch the glow, till it was all one sheet of brightness, and the trees seemed bending down to look at their own likenesses below, for every branch and twig and leaf might be seen there, pictured.

Sometimes a breeze would ruffle the surface, and then there were little wavelets, with red on one side and grey on the other, and the pictured branches and leaves had a snaky sort of movement in and out of one another. And if a duck swam across, leaving its little track, that made another break in the smooth picture.

I used to stand and watch these things, and wonder at the ripples and the brightness. Sometimes I asked father the "why" of this or that, for I was an inquisitive child, but he always said, "Don't know, my girl," and went off to his pipe; so it was not of much use to ask him. If I put the same questions to mother, she commonly said, "How can I tell? Don't bother!" and that shut me up.

And if I went to grannie, she would say, "Because God made it so, Phœbe." This was all right and true, but I would have liked to understand a little more about the beautiful things which God has made. I used to wonder then, and I often wonder now, how it is that people care so little to look into such matters.

Well, but I must go on about my home, the only home I ever knew in childish years.

It was a pretty cottage. Clematis grew over one side, and in front there was a rose-tree, which used to flower all the summer through and on almost into the winter. The roses were small and white, but how they did cluster! People often stopped to remark on them. We had a nice piece of flower-garden in front, stuffed full of sweet-williams and pinks, and such plain old-fashioned plants: none the less pretty for being old-fashioned, however. At the back there was a tiny strip of kitchen-garden too. The front door had a porch, and honeysuckle grew thickly all over it, with long trailing pieces, which had to be lifted and put aside when we went out or in.

Grannie had lived in this cottage all through her married life, and when her husband died she lived on there still, with her only boy,—my father,—working for him, and making him work for her.

Father's work was in the building firm of Johnstone & Co. We thought Mr. Johnstone a very grand person in our little town, because he was so rich, and wore such a thick gold watch-chain, and had such a big red stone in the ring on his little finger. But I dare say he would not have been thought so much of elsewhere. He was not a gentleman, and he very seldom spoke a kind word to any of his men, as I am sure he would have done if he had been a true gentleman.

Father was not a skilled workman, but he had good wages nevertheless, for he was steady and trustworthy.

He was always kind to us children. I never knew him anything else in those days. Sometimes he would speak up sharp in a passing way, but he never knocked us about or stormed at us, as I have seen men do with their children.

He was not a religious sort of man. He went to Church most Sundays, in the afternoon, to please grannie, and sat and nodded through the sermon. He would have done a good deal to please her, though he wouldn't do one thing which she wanted, and that was to leave his bed early enough for the morning Service—no, not even for her sake.

No, father was not religious. If he had been—not merely religious outwardly, but really serving God in his heart—I think our life after might have been different from what it was. It always seems to me, looking back, that poor father was like a fine ship at sea, without any rudder. For a while it may float along quietly enough, on a calm sea and with a fair wind. But let the wind change and grow strong, and it is carried helplessly away and cast upon the rocks. If he had had the rudder, yes, and the Pilot on board, the breeze would have been only for his good. But he had not.

I have many a time had this thought about poor father. He was such a kind man in those days, and so steady. He liked his pipe and his glass of beer, it is true, but he didn't go to excess with either, and he loved his home and seldom went to the public. He brought his wages straight home to grannie always; for it was grannie who managed things, not mother. They were very unlike each other. Grannie liked work, and mother couldn't abide it. Grannie could not be happy without everything neat and nice about her, and mother did not care how anything was. Grannie had always managed everything before father married, and she kept it on after he married. Mother did not mind. She liked to be saved trouble.

Mother was a pretty little woman, with blue eyes and a nice smile. But she was always untidy. Even grannie could not cure her of her untidiness. I don't know what the house would have been like, except for grannie: but that made all the difference. She never let a speck of dust lie anywhere, and she was a beautiful cook.

Grannie set herself early to train me into her ways, and I think I took after her naturally. "You know, Phœbe," she used to say sometimes, "if anything happens to me, it will all come upon you. Somehow, your mother doesn't seem to have the knack; and if somebody else beside her didn't keep things straight, there would be a terrible muddle. Maybe she would not mind, but your father would, and it's a terrible thing to live in a muddle. So see you do your best to learn."

I did do my best, and I think she found me an apt scholar. By fourteen years old I could turn-out tidy little dinners without any difficulty, and I was a capital hand at cleaning up; and as for sewing and darning, I don't really think there was another girl in the place who could have surpassed me.

I was a good deal more grannie's child than mother's. Mother cared most for Asaph. There were only two of us, and Asaph was two years younger than me. He was very like mother in looks and ways, little and pretty, with blue eyes and curly hair, and a sort of easy soft way of doing things. But he was not so easy as not to like having his own way, and he didn't take it softly if anybody crossed him. He loved to lie in bed too, and he hated lessons and work. And mother indulged him right and left. Grannie seldom meddled about Asaph, for it almost always raised a storm if she did.

Grannie was getting on in years, and her hair was white, but she still looked hearty and strong, and was very active and ready to help in many ways. She was religious and no mistake. It was religiousness of the right sort with her—not only going to Church and saying her prayers, as with some people; and not only talking good, as with some other people. She did go to Church of course, and I never knew a more regular Church-goer than she; and she did say her prayers regularly too. And I don't mean either that she could not talk if occasion served. We can generally speak now and then of the things we love best. But her religion didn't consist only in Church-going or in talk. She lived altogether to God and for God, and I don't really think she ever took a single step without considering first whether it was what God would have her do.

CHAPTER II.

NEWS.

I REMEMBER so well one particular Sunday evening. It is not surprising that I should remember that Sunday evening, for it came just before a great event in our lives.

We had been to Church twice as usual, Grannie and I. Mother never would go in the morning. She said she had too much to do—though really it was not she who did the work. Father lay in bed late, and Asaph followed his example. Grannie and I always got up particularly early on Sunday morning, that we might have everything straight in time for the Service. Grannie always gave father a good cold dinner on Sunday. She had been a servant in a rich gentleman's family when she was young, and she used to say that if the gentleman and his family always had cold Sunday dinners, for the sake of saving Sunday work to their servants, she didn't see why we shouldn't do the same, for our own sake. We were not like the neighbours in this, and father sometimes grumbled a little in a good-tempered way. But he had been brought up to it from boyhood, and the dinners were always so nice that he could not say much. The only things ever spoilt were the potatoes and greens, which mother used to have in charge to cook, as they of course had to be hot. I fancy she often went out for a gossip with the neighbours, and forgot them. If mother would have gone to Church, grannie would have stayed at home, or made me stay at home, to do what was needed. But grannie always said she would not consent to have two kept away from God's House, where one was enough. And grannie could be very firm, when once she had made up her mind.

So we had been to Church in the morning, and then we had all had a nice dinner of beautiful cold pie, good enough for the Lord Mayor's table, and a sort of cold custardy pudding with jam and pastry round. It looked grand, and father was very fond of it, but it did not cost much money, though it did cost a deal of time and trouble in the making. Grannie never grudged time or trouble, however.

In the afternoon we had been to Church again, and father and Asaph with us. Father was a very respectable-looking man in his Sunday suit, and Asaph was such a pretty boy. He looked more like ten than twelve years old, though. Mother would not go with us, for she had toothache. She was a good deal given to toothache, but I think it came oftenest on a Sunday.

The sermon that afternoon was about Temptation. I often thought after, how strange it was that Mr. Scott should have preached it just then.

"Lead us not into temptation" was the text. Mr. Scott spoke a great deal about the meaning of the word Temptation. He said it had two quite different meanings—one was, enticing to evil, and the other was, testing or trying. He said that God never "tempted" any man in the first sense—enticing to do wrong. But he said also that God very often tempted us in the second sense—trying our faith, testing our strength, putting a pull on the rope, as it were, to show how heavy a weight it could bear.

Then Mr. Scott talked about different ways in which God "tempts" people—sometimes by sending sorrow; sometimes by giving pain; sometimes by putting them into difficult circumstances; sometimes, and Mr. Scott made a good deal of this, by letting them have all they most like and wish for. I think that part of the sermon struck me most. It seemed so strange to think of happiness being temptation. But I saw grannie nodding her head with a pleased look, so I was sure he must be right.

Mr. Scott was a good loving-hearted old man, and he was what is called an able preacher. Everybody in the place loved him, for he was a friend to everybody—so far, at least, as people would let him be.

I could not make out whether father was listening to the sermon. He never did as a rule, but used to settle himself into his corner and fall into a half-doze. Sometimes grannie would poke him gently to rouse him, and he would give a great start and make believe to pay attention, but it never lasted long.

This day, however, he really did listen. For in the evening, when we had had our tea, and father and grannie and I were sitting outside the door, as we often did of a summer evening, with the pond in front glistening, and the ducks swimming to and fro, father said—

"I didn't hold with Mr. Scott this afternoon. If good times are a temptation, they're a rare sort to most folks. I think it's trouble that makes one go wrong. I shouldn't mind having a little more of the other, for my part."

"Times aren't bad with us, Miles," said grannie.

"Maybe not, but I shouldn't mind 'em being better," said father. "I shouldn't mind a bit more of holiday now and then—and to take things easily and have less to do."

It was not at all astonishing that father should have made these remarks just before what was coming, for he very often did make them. A week seldom passed without his saying such things.

"I shouldn't wonder if a time of ease and idleness was one of the sharpest temptations God ever sends," grannie said quietly.

Father said, "Now, mother!" in a protesting sort of way.

"I shouldn't," she said, quite firm, and looking him in the face. "Satan has a deal better chance with idle folks than with busy ones, Miles."

"Ah, so you've told me many a time," said father. "And maybe you're right. I don't say but what you are. I'm not an idle sort of fellow myself, by any manner of means. But I don't say I wouldn't like more ease. And as for calling pleasure and riches and that sort, temptation, I don't see it—I don't really see it."

"No," said grannie. "There's many a thing a man can't see, till God gives him sight."

"And you think you've longer sight than me, mother?" says he.

She looked up, with a smile which I thought quite beautiful—looked up, not at him, nor at the trees, but away and above and beyond, as it were.

"Yes," she said; "I've longer sight than you, my dear. I've sight to see up and up into heaven itself, and you haven't. It makes a deal of difference."

"Bless me, mother, don't talk like that," says father, in a sort of hurry. "It sounds as if you was going to die this very night."

"And if I was, I'm ready," said she. "It wouldn't be grief to me to hear the chariot wheels coming near."

But I was sitting close by, and I turned and said, "Grannie, please don't want to go just yet."

"No," she said, "I'm willing to wait."

"Well, you go beyond common folks, somehow," father said. "There ain't many that care to talk about dying as cool as you do."

"No," she said. "And I couldn't either, if death was to me what it is to many a one, a plunge into the outer darkness, away from the smile of God. That would be awful."

"Well, well, we needn't talk about it now," father said, fidgeting. "You're the best woman that ever lived, though you don't think yourself so. But all the world can't be like you."

And he got up, and hummed a tune, and plucked a bit of sweet-william, and walked about; so grannie could not say any more.

The next morning broke like other mornings, and we began the day as usual. Father went to his work, and Asaph to school, which he was nearly done with. This was washing morning, so I was very busy. Mother said her tooth ached still, and she did not seem to think she could do anything. Pain always upset her, and she cried over it half the morning, and went out in the garden and chatted with Mrs. Dickenson most of the other half.

Mrs. Dickenson was our left-hand neighbour, a cleanly thrifty sort of body, but a great talker. She never could resist a gossip, though she worked hard between whiles. Grannie did not like her very much. She had only one child.

In the middle of the day father came back. That was quite unexpected. He always took his dinner with him, and ate it at the works. Grannie used to put it up for him nicely in a piece of paper, with a clean red handkerchief outside. Sometimes it was only bread and cheese, but more often she managed for him to have a slice of cold meat too.

This Monday, instead of staying away as usual, he came home. Our first thought was that he must be ill; but he was walking fast and looking quite red in the face, so it did not seem like illness. Then we fancied that perhaps he had got into trouble and been turned off; but no, he looked too pleased. I had never seen father look so pleased and delighted before. He came hurrying up to us, as we waited at the cottage door, for mother had called us all together in a fright, to see what was wrong, the moment she caught sight of father walking along the road. He hurried up, as I say, and seized Asaph, and gave him a sort of twirl round, like a man in such spirits that he scarce knew what to do with himself. And then he said—

"Guess what's happened?"

"I know," mother said. "You are going to have higher wages."

Father chuckled, and said, "No."

"It's a half-holiday at the works," said grannie.

"No, it isn't. I got leave to run round for five minutes, that's all."

"Then what has happened?" cried mother, and we all chimed in. Grannie was the quietest, and I think she looked a little anxious.

"You want to know, don't you?" says father, chucking Asaph under the chin; "don't you?" and he chucked me too. "Well, I'll tell you. I'm to have five thousand pounds!"

Grannie looked as if she fancied him gone mad. Mother shrieked and clapped her hands, and Asaph copied her.

"Five thousand pounds!" father said again.

"Who's given it to you, my dear?" asked grannie.

"Nobody. It's left to me in a will. Old Andrew Morison is dead, and he has been storing up his money for years, and he quarrelled with his son just at last, and willed it all away to me. Think of that! Five thousand pounds, Sue! Think of that! Five thousand pounds, mother!"

"It's the temptation," said grannie very low, and I heard her sigh.

"It's just lovely," cried mother. "Why, I can have a silk dress."

"Six, if you like," said father. "And Phœbe, too."

I don't know what I said. I felt all in a maze.

"Miles," said grannie, in a trembling voice, and she laid her hand on his arm. "It's a solemn charge for you. Don't you think we ought just to kneel down, and thank God, and ask Him to teach us how to spend it? It'll do us no manner of good without His blessing alongside."

"So you can, mother," said he, all in a hurry, giving her a kiss. "So you can. I'm due back at the works, and mustn't wait. We'll talk it over in the evening, by-and-by. And Sue shall have her silk dress as soon as ever she likes. It makes a man feel all dazed to think of! Five thousand pounds!"

And he was gone. Mother ran away to tell the neighbours, and grannie took me upstairs into the little room which she and I had together. She didn't make but a short prayer, only it was one which I never could forget.

CHAPTER III.

THE MONEY.

"Who told you about it, Miles?" asked grannie at tea-time.

Father had come back, and we all felt very much excited still, as was only natural, I suppose. Grannie looked sad, I thought, but she was the only one to seem so. I had had a restless feeling on me all day, which made it difficult, to settle to work. I don't think I should have settled to it at all, but for grannie's being so bent upon everything going on just the same as usual. She would not abate one jot of cleaning and washing and scouring for herself or for me. But mother did nothing whatever the whole day, except stand at the door, and talk to the neighbours. The news spread quickly, and numbers came to ask what it meant. Some seemed really pleased for us, but they were few. The greater number, as far as I could tell from scraps of talk which I heard in going to and fro, were more inclined to be jealous, and to wonder why such good fortune should have come to us and not to them.

And at tea-time grannie put the question,—"Who told you about it, Miles?"

"Why, it was the lawyer who had the making of the will—a Mr. Carver. It was him and young Mr. Johnstone," father said. "The lawyer came over by train from Lanston this morning, and he told Mr. Johnstone first, and then they sent for me and told me. Mr. Johnstone said I was a lucky man, and he shook hands with me—first time he ever thought of doing that."

"Young Mr. Johnstone isn't near so stuck-up as his father," mother said.

"He's more of a gentleman," added grannie; "that's why."

"There's room for him to be," said father. "Well, he told me I was a lucky man, and Mr. Carver talked a deal. I was so dazed at the news, I didn't half take in all he said. Something about saving and investing and stocks,—I don't know what it was."

"I think you'd be wise, Miles, to ask him to say it again, and to take his advice," said grannie. "He knows more of such things than we do."

"Oh, I'm not so sure," says father, thrusting his hands into his pockets. "I'm not at all so sure of that, mother. He's a lawyer, and he'd like to have a finger in the pie, I don't doubt. But I don't want any of my five thousand pounds to stick to his fingers. He's too sleek and smooth-spoken by half for me. I don't trust him."

"Then you'll ask Mr. Scott," said grannie.

"I'll think it over," says father. "No need to be in such a hurry. Time enough to make up our minds."

"I'll tell you one thing that is on my mind," said grannie, speaking slowly, and looking at us all round in turn. "What about the poor fellow who was expecting five thousand pounds from his father, and who hasn't got it?"

"Jem Morison! Ah, poor wretch, yes," says father in an indifferent sort of way.

"He shouldn't have offended his father," said mother. "But I am glad he did."

"It's sorrowful work for him," said grannie.

"Well, he took his choice," father said. "He married against his father's will, and now his wife's sickly, and they've got twins, and he is in bad health, and can't work. Oh, I dare say he's sorry enough. Most people are when they've taken their own way and have to suffer for it. 'Marry in haste and repent at leisure,' you know. But there's another saying quite as true, and that is, 'It's an ill wind that blows nobody any good.' If young Morison hadn't gone against his father, we shouldn't have this fine windfall. I declare, mother, I don't think you half take in how good it is. Five thousand pounds! Why it'll do anything! Sue is going to be a lady now."

"Fifty thousand pounds wouldn't make a lady of one who wasn't so in herself," said grannie quietly. "Wearing a silk dress is not being a lady, Miles, and you know that as well as I do. I've no wish to see Sue a lady, nor you a gentleman. All I want is to see you both living for God in that station of life where He has put you."

"Well now, mother, you won't go for to say it isn't God who has given us this five thousand pounds, I suppose," says father sharply.

"Yes," she said, "I know He has, and I thank Him for it. But it's temptation, Miles."

Father laughed out loud.

"It's temptation," repeated grannie. "It may be very sore temptation, Miles. I think I'd almost sooner have seen you with temptation of the other sort,—with having too little, instead of too much—if God had willed to send it. I'd have feared less for your being led astray by it."

"Now, mother, you do take a very melancholical view of affairs, and that I must say," protested father. "And what's more, I don't think it's kind. Just because something good has come for once in our lives, you must needs croak about it, and wish it was something bad instead."

"Grannie would like us all to sit down and cry," said mother.

She and father often called her "grannie" just as we children did.

"No, I don't want that, Sue," said grannie. "But I'd have you thankful to God, my dear, and I'd have your eyes open to danger—that's all. And there's one more word I must say, though I'm afraid you won't like it. Seems to me, Miles,—"

Grannie made a stop. "Seems what?" asked father.

"Suppose we were in the place of that poor young Morison, and he was in your place—how do you think you would feel?"

"How? Why, I should count myself an uncommon fool, to have thrown away five thousand pounds for the sake of a pretty face," says father.

"I shouldn't wonder but you'd feel too you had a sort of right to the money, and that the other man hadn't any right to it at all," grannie said.

Father burst into another loud laugh, but it wasn't a happy or a merry laugh.

"Oh, that's what you're driving at, is it?" said he. "No, no, grannie—no nonsense of that sort for me. I'll keep the money fast when I get it. As Morison has sown, he may reap. He's nothing to me, nor I to him."

"He and you are cousins born," grannie said. "Your father's father and the mother of the old man that's dead were brother and sister."

"So much the better for me," father answered. "If I hadn't come next in blood-relationship, old Morison wouldn't have willed the money to me. But it's little enough we owe to any of them in the past, you know, mother. Why, dear me, the Morisons have counted themselves a deal too grand for many a year to have to do with such as we."

"The more reason to be ready to show them kindness now," says grannie.

Father repeated the word "kindness" in a rough sort of way. "Why, you don't really think," says he, "that any living man would be such a born ass as to give up five thousand pounds of his own free will!"

"If he saw it right! Yes, there have been such things done," grannie said, with a kindling in her eyes. "But I would be content if you would give him half, Miles."

Father brought down his clenched fist on the table, with a bang which made the cups and saucers rattle.

"I'll not do it," he said. "I'll not give him one half, nor one quarter, nor one tenth—no, nor one shilling of the money. It's mine, and I'll keep it. Why, bless me, the world would be upside down altogether, if such notions as yours got followed out. You've a sort of craze, grannie, with your religious ways, and that is how it is. But you needn't hug this notion, nor speak of it to anybody. Morison is not going to have one shilling of the money."