The Old House in the City: Or, Not Forsaken

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

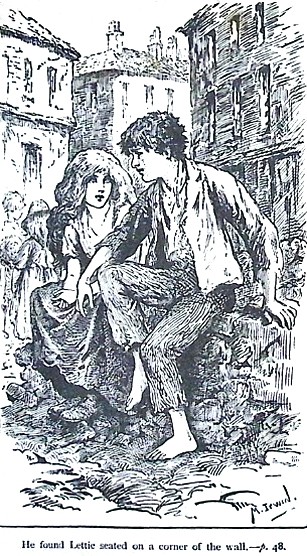

He found Lettie seated on a corner of the wall.

The Old House in the City

OR,

Not Forsaken

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF

"WON AT LAST," "LIFE TANGLES," "EARLS OF THE VILLAGE," ETC.

New Edition

LONDON:

JOHN F. SHAW AND CO.

48, PATERNOSTER ROW, E. C.

CONTENTS.

CHAP.

I. THE OLD MANSION

II. UP THE STAIRS

III. AILIE'S CELLAR-HOME

IV. WHAT TO DO WITH AILIE?

V. STARVING

VI. JOSIE'S HOME

VII. OLD JOB KIPPIS

VIII. AILIE FINDING HERSELF USEFUL

IX. JOHN'S ADVICE

X. SUNDAY IN THE GARRET

XI. JOSIE'S EXCURSION

XII. WHAT HOR WANTED

XIII. WAITING

XIV. JOB'S DUTY

XV. CLOUDED

XVI. MET AGAIN

XVII. LEVESON'S SECRET

XVIII. LETTIE'S FRIGHT

XIX. LITTLE VI

XX. THE SEARCH ENDED

XXI. LETTIE'S RECOLLECTIONS

XXII. BROUGHT HOME

XXIII. PICTURES

XXIV. VISITORS

XXV. THROUGH THE WATERS

XXVI. THE LAST OF THE OLD GARRET

XXVII. A NEW HOME

THE OLD HOUSE IN THE CITY

OR,

NOT FORSAKEN.

CHAPTER I.

THE OLD MANSION.

IT was an old old house, situated somewhere near the central parts of London. The street was narrow and gloomy, branching off at right angles from a frequented thoroughfare, and the lofty uppermost stories, rising tier above tier, and closing in overhead, left but a narrow strip of heaven's blue visible to those below, even on the brightest and sunniest of days. It was neither bright nor sunny now, for twilight shrouded the giant city, and already its myriad lights twinkled through the gloom, in preparation for the coming hours of darkness. Dull indeed was this confined alley, with its old-fashioned buildings on either side, in the midst of which, on the right hand, at the farthest corner, stood the aged house already mentioned.

It had not always been so old. Once, in long past days, it had been a stately mansion of no small pretensions, forming the home of some wealthy city merchant, or, a little farther back, it may be, even of a nobleman himself. But that was over now. Noblemen and city merchants had alike been swept away in the hurrying tide westward, and the old mansion had sunk many grades in the scale of society.

A great change had taken place since those far-off days, one or two hundred years before! No delicately-nurtured ladies now, in silk and velvet, in paint and patches, went daintily up and down its broad oaken staircase. No gaily-attired young gallants, with tossing plumes and clinking swords, passed to and fro through its outer door. That massive portal was never closed now, for the old house was no longer a home, but only a mass of tightly-packed dwellings. No heavy coaches, drawn by fashionable Flemish mares, lumbered in stately grandeur through the narrow street. Far back in a distant horizon lay such dignities.

Ladies and gallants, velvets and plumes, Flemish mares and gorgeous splendour—who could dream of such terms in connection with this squalid neighbourhood? Who could look on those dirt-begrimed ceilings, and imagine brilliant candelabra suspended from their centres? Who could view the discoloured walls, and realize that they were once crowded with works of art? Who could glance at the bare unwashed rooms, and listen without an incredulous smile to the tale of velvet furniture and priceless decorations, which once graced those very apartments?

Gone for ever were those days of wealth and luxury. The old mansion had sunk into a mere tenement-house, crowded with carpenters, shoemakers, tailors, and porters, too often in the lowest depths of wretchedness.

It was a close summer's evening, and heavy oppression pervaded the atmosphere, though the sun had sunk below the horizon, and the last gleams of red light, finding their way through the dull mist overhead, had faded at length from the tallest chimney-tops. But no sweet breath of country freshness could penetrate so far through the city. No cooling breeze ever crept between the massive walls of the houses forming Ansty Court.

Work was over for the day—such work as was to be had, for too many in the old mansion and its neighbourhood were suffering the miseries of long-enforced idleness. Work was slack, and bread was hard—oh, hard to find!

Up and down the uneven staircase, with its shattered banisters and greasy walls, passed footsteps from time to time. No wonder! For over half a hundred human beings found shelter within the walls of this one house. Each room was a separate home. And such a home! The old familiar English tune, true of many a "sweet sweet home," could scarcely here have met with any response.

It was growing dark, and none of the passers-by, going slowly up or down with rounded shoulders and weary feet, noticed a small figure crouching in the most shady corner of the second landing. A mere bundle of ragged clothes it might be, but for a slight movement now and then, or a broken sob at intervals when no one was near. Looking more closely, it would have been seen that one bare arm was passed tightly over the other with a distressed pressure, while the little dusky fingers clutched firmly at the rags which scarcely sufficed to cover her. But there was no other sign of life, and an approaching footstep was the signal for a closer cowering against the wall, and a more absolute stillness, in evident dread of detection.

Footsteps were growing fewer now. Children had been called in from the dirty courtyard where they played all day, and had been consigned to the respective heaps of rags or straw which formed their beds. Many men yet lingered at the public-house, not far distant, striving to drown care and misery for a while, by a means which sunk themselves and their families day by day into yet deeper degradation. Others had already retired to such rest as might be obtained in crowded rooms, with half-famished children crying themselves to sleep for want of food.

For a while no one passed. Then again came another step, heavily mounting the old staircase. A woman's figure, dimly seen in the uncertain light, drew near, staggering a little, as if hardly able to maintain her footing. She was supporting herself against the wall, and the child in the corner cowered down more closely with renewed fear. In vain this time. Following the course of the wall, the woman came against the unexpected obstacle, nearly falling down, and then standing still with the question—

"What's this? Who are you?"

Reassured by the voice, which showed that the unsteady walk was not, at least, caused by a visit to the terrible gin-palace, the child rose and came a step forward, still clenching her arms across her chest; but there was no answer to the question.

"What are ye after here?" asked the woman again; and, though she spoke in hard tones, as of one whose sympathies had been well-nigh dried up by long trouble, yet she would not pass by the lonely child, as many a richer man or woman might have done, like the Priest and the Levite of old.

A quick sob, gasped out with heaving breath, answered her. The woman leant against the wall, and laid a hand upon the arm of the little wanderer.

"Tell me what's your name, child?"

"Ailie Carter," was the muttered reply, followed by the entreaty, "Oh, don't ye send me back!"

"Ailie Carter. Then your father's Jem Carter, as came a while ago to live in one of the cellars?"

"Yes, our house is down there. Oh, don't ye send me back!" came in renewed entreaty.

"Where's your mother, child?"

"She's took up," and Ailie sobbed, though with her arms pressed yet more tightly, as if fighting to conquer her tears. "And father's dyin'—and it's awful to be with him all alone. I daren't—oh, don't make me! I wants mother!" moaned Ailie.

"Jem Carter dyin'! Well, it's what we all come to," said the woman, with despairing composure. She had spoken to Jem Carter and his wife occasionally, and in daylight she would have known by sight the forlorn child now cowering in front of her. But her home was near the top of the house, and Ailie's at the bottom. And the Carters, like many in their position, had known better days, and lived much to themselves in their cellar.

"Jem Carter dyin'!" repeated the woman. "And where's your mother took, child?"

Ailie shuddered visibly. "The p'lice," she whispered. "Mother said she couldn't bear it no more—to see father dyin' and cravin' after food, and not a sup nor a morsel in the house to give him. She were just crazed with hearin' him moan and groan, all day an' night, an' she walked right into a baker's shop, an' seized a loaf with one hand,—and a lady's purse with lots o' beautiful gold was a-lyin' on the counter, an' mother clutched it. They said she meant to steal that too, but she didn't—she didn't," repeated Ailie, breaking into a wail, like an animal in pain. "She were just crazed, an' snatched at it like, but didn't never think what she were doing, and she only wanted the loaf for father. He did moan so for some'at, an' he's wastin' away for want."

"Same as the rest on us," said the woman shortly. "I've eaten nought to-day, and I'm like to drop. Well, if he's dyin', it'll soon be over wi' him."

"Don't ye send me back," entreated the child, with sobbing catches in her breath. "I'll only sit here, an' be ever so quiet. Oh, don't! Father's never spoke a word since I telled him mother was took, an' he clutches with his fingers, an' makes a groanin' noise down in his throat, an' looks—an' looks—oh, I can't go back," sobbed Ailie. "I'd sooner sleep in the street all night. If only mother was here!"

"It'll be long enough afore ye see anythin' of her again, I can promise ye," muttered the woman. "Here, come along with me, child. Mary Carter's done me a good turn afore now, mindin' the children when I couldn't be with them, and I'll spare ye a crust of bread, if it's the last we have left."

Slowly as before, she went up the broad staircase, the fringed edges of her cotton gown dragging from step to step, where in olden days rich trains of jewelled satin had been wont to sweep. Ailie kept alongside with her, clinging close to the shelter of the blackened wall, but asking no questions, and seemingly willing enough to follow wherever she might be led. She would not have gone so readily down the stairs as up them, perhaps.

CHAPTER II.

UP THE STAIRS.

A SMALL room in the top story but one of the house, was that to which Ailie was led by her companion, with one long narrow window, the broken diamond-shaped panes of glass being mended not untidily with rag. Being so high up in the confined street, such daylight as yet remained found freer entrance than below, and the darkness was some degrees less advanced than on the staircase and landings. Other similar windows might be seen in the building opposite, at a distance of some few yards, with haggard faces in them here and there.

If the room looked crowded, it was not at least with the presence of over much furniture. One broken bedstead stood in the corner, made to turn up clumsily in the daytime. Out of its coverings peeped three small heads, in various positions of careless repose. These were the infants, varying from six to three in age.

A rickety table occupied the centre of the room, and a man sat beside it on a chair, which had lost the upper half of its back. A large-built man in appearance, yet sickly-looking, with a hopeless expression of countenance, as he leant his head upon his hand, and gazed moodily on the floor.

Two idle looms stood against the wall, taking up much space, and doing little else, in this sad time of slack work. The only remaining chair was used by a dwarfish high-shouldered boy of ten or eleven, whose heavy head hung over the back, with dropping jaw, and half-opened eyes gazing into vacancy. Near him, extended listlessly on the floor, was a second boy, some two years older, tall, thin and feeble-looking, with wasted limbs showing through his tattered clothing, and honest eyes sparkling from beneath his brows. One of his knees, raised and crossing the other, formed a resting-place for a little girl of about seven or eight, whose large blue eyes, heavy with sleep, and delicate fairness of complexion, formed a curious contrast to other members of the family.

There was a hungry glance from those two at Esther Forsyth, as she entered the room, followed by a curious gaze at her companion. Such a mere scrag of a child it was, standing in the doorway, with black eyes, alike timid and eager, short black hair pushed behind her ears in an attempt at neatness, and thin bare arms. She did not look more than nine years old, but age is hard to guess among these stunted city children.

"Well," John Forsyth said briefly. "Got any work, Esther? No need to ask, I s'pose," and he sighed. "What's that child for?"

"John, did you know Jem Carter was a-dyin'?"

"Dyin'! No, I knowed he couldn't last long. What's to do about him?"

Esther slowly removed her ragged bonnet and shawl before answering.

"No, I've got no work," she said at length, in a calm tone, which was far removed from indifference. "Seems to me there's none to be had. I don't know what we'll come to. Have ye had your supper, all of ye?"

"I gave it the little ones—the crusts as was left for them," came in soft tones from the blue-eyed child upon the floor. "Father wouldn't take none, nor Hor wouldn't."

"Nor Lettie didn't want to, neither, but I made her," said the elder boy,—adding abruptly, "Mother, there hasn't a crumb passed your lips this day. D'ye think we'll eat up all, an' see you starve afore our faces?"

Esther went to the little cupboard, and brought out a small plate of crusts. "It's all there is," she said. "There ain't much left now as is worth puttin' in pawn, and if work don't come—" Then after a pause, "John, we'll spare the child a bit."

"Take it out your own children's mouths to put into a stranger's!" said John, moodily.

"She's eaten nought to-day, have ye, Ailie?"

"No, nor since yesterday morning," responded Ailie, with longing eyes.

Esther cast an appealing look at her husband.

"Do as ye will," he said shortly. "I'm not the man to refuse a crust when I can afford un."

Esther silently distributed the contents of the little blue plate. Ailie grasped with famished eagerness at the dry bread held out to her. She did not eat it quickly, however. The pleasure was too real and delicious to be soon ended, so she bit off small pieces, and constrained herself to munch them slowly, working her way across the room while doing so, till she found herself within two paces of the little girl, who thereupon beckoned her to come and sit down upon the floor. Ailie obeyed the invitation immediately, and stared hard at her and the boy.

"We're a queer couple, ain't we?" said the latter, with a twinkle of amusement in his hollow eyes. "Leastways, you seems to think so. What's wrong with us, eh?"

"What's your name?" asked Ailie, taking another bite.

"Mine's a jolly name, ain't it, Lettie? I'm Horatio Nelson Forsyth."

Ailie thought that grand indeed, and gazed with rounded fascinated eyes.

"Lettie calls me Hor, and so does most folks; but I like more particular to be called Nelson. He was a real man, you see, as I was named after—the biggest sailor ever lived, an' beat all his enemies to nothin', an' I'd like to do the same."

"You couldn't," said Ailie, grieved to see how her crust was diminishing.

"Maybe not; but I'd like it just—wouldn't I? I'll be a sailor some day, an' live on the sea in a big ship."

"What's the sea like?" asked Ailie.

"Why, lots o' water. I haven't never seen it—more's the pity—but folks say it's grand—all a-splashin' and a-dashin', with white spray flyin' through the air."

"What's spray?" asked Ailie.

"Well, I don't know as I could say 'xactly, but I fancy it's a bit like mother's soap-suds when she washes up," said Hor confidentially.

"Soap-suds ain't pretty a bit," said Ailie.

"Spray's pretty, if soap isn't—I know that. Lettie, here, don't care for me to talk about the sea. It's the country she wants—eh, Lettie?"

"I'd like a lot o' green ever so much," said Lettie.

"See if I don't get you a real plant some o' these days, and a nice red flower, all for yourself, Lettie."

"I'd a deal rather it should be white," murmured Lettie wistfully. "Mayn't it, Hor?"

"I'd have it red, if I was you," said Ailie, with eager eyes—"ever such a bright red—like—like—oh, like a man's coat."

"Like a soldier's coat," suggested Hor. "Lettie likes white flowers best, ye see."

"Lettie, it's time ye should be off to bed," said Esther. "Don't ye want any more, Ailie?"

Ailie looked from the two remaining inches of hard dry crust to Esther Forsyth's face, and then back again.

"I just do," she said expressively. "But there's father."

A momentary look of softening came over Esther's lined hard features—hard only outwardly, for there lay a tender woman's heart beneath. Only, so much of its tenderness had been frozen by long years of pressure, that it was not readily melted into expression. The growth of dull reserve and impassive endurance, which had gathered closely over her once open-hearted nature, was not easily broken through. Still, for an instant her eyes wore a look of softness, as she said—

"Ailie's a good girl to think of her father, isn't she now, John?"

"Aye," responded John, shortly. "What be you a-going to do with her?"

Esther looked at Ailie, and Ailie cowered in renewed fear.

"Oh, don't ye—don't ye send me back," she entreated. "I'll let him have my bread. I won't be in nobody's way. I'll sleep on the stairs, ever so quiet. Oh, don't ye send me back."

"'Twould be cruel to send her alone," said Esther. "A bit of a child like that—and he dyin'."

John's assent was a monosyllable. Poor, hopeless, weary, they might be themselves; nevertheless, that they should help a neighbour in his sorer trouble was but a thing of course.

"Mother, I'll take down Ailie, an' see what's wantin'," suggested Horatio, sitting up. He had been wandering for hours through the streets, poor boy, vainly seeking for employment, while barely recovered from a severe attack of low fever, and subsisting on a mere scrap of bread. Esther shook her head.

"Ye've been on the tramp all day, and you're fit for nothin' but sleep. I'll go with Ailie myself."

"You've been nigh as long on the tramp yourself, mother."

"A boy's little use in a sick-room," said Esther. "Get to bed, Lettie and Roger—an' you too, Hor. I'll be back when I can."

Taking the child's hand in her own, she left the room again, and Ailie went submissively, though trembling. Down one flight of stairs after another they made their way, Esther walking more steadily now, perhaps strengthened by her little taste of supper. Perhaps the very act of caring for others imparted vigour to herself.

Not that it was done with the highest motives. Not that Esther had any thought of "serving the Lord." No such Heavenly light shone in upon the Forsyth's dreary home as would have come from trust in a Heavenly Father's watchful love. If the good seed had ever been sown in Esther's heart, the pressing cares of poverty had long ago stifled its growth, and smothered out the germ of life. She and her husband had struggled long in past years to retain a respectable appearance, but of late a cloud seemed to have settled down upon them all.

John was not an unsteady man in the main, but sometimes, in the mere longing to escape from idleness, and its attendant train of miseries, he fled to the public-house, and, once there, what wonder if he stayed too long, and took too much? The crowded room which formed his home could indeed offer small attractions.

Esther bore it all silently—bore it as she bore everything else, with a kind of dogged patience. Down in her heart the canker-worm of hopelessness was sapping the springs of energy. But for her children, she could have lain down without a wish ever to rise again. For love of them she strove on, sought work, denied herself, and lived a life of silent endurance. But it was so long now since all regular work had failed, that the old struggle for at least the appearance of respectability was dying out. They were growing used to rags and tatters, and scanty clothing—worse still, even to want of cleanliness. What was the use of striving? When failing for lack of food, and sinking with the long day's search for the means of livelihood, Esther was in no state for "cleaning up," she would have said.

And yet the woman's heart of sympathy beat still beneath that soiled cotton gown. She could not see Ailie Carter in distress, and not do the little in her power to help.

CHAPTER III.

AILIE'S CELLAR-HOME.

DOWN flight after flight went Esther Forsyth and little Ailie Carter. One or two rough men, returning from the public-house, staggered past them, and Ailie crept closer to her protector's side. One or two "women, dressed in unwomanly rags," came up the stairs, and exchanged a word of greeting with Esther.

Still they went on—past the second story, past the first story, past the ground-floor; past open doors, showing sleeping children huddled in rags; past closed doors, from which came the wailing of hungry infants; past other doors, whence issued sadder sounds of raised voices and angry discord. Past all these, and down stone stairs, leading to underground regions, where the air weighed heavy and dank. And then they stopped at a door.

Esther Forsyth pushed it open and went in, the child creeping after.

A bare cellar lay before them. Furniture had been parted with, piece by piece, in the long struggle for subsistence. Nothing of it was left, save the thin flock-bed in one corner, and the single broken chair in the middle. A tallow candle, in a candlestick, stood upon the chair, casting a glow upon the damp walls, the small window, and the sallow face of the sick man on his wretched couch. Nothing of sheet or blanket was visible—only an old piece of dirty carpet drawn over the sufferer. An old pipe and a tin saucepan stood side by side upon the mantel-shelf; and that was all.

Jem Carter was not alone. An aged woman stood beside him, and she turned her withered face towards the door when Esther entered.

"Be that Ailie Carter?" she demanded, in a hoarse whisper. "He be axin' after her sore, an' no one could tell nought of where she was. An' she a leavin' of her father to die alone, like a rat in a hole."

A cry broke from Ailie's lips.

"No, no—I didn't mean—" she gasped, with half-sobs of excitement and fear. "O, father, I wouldn't ha' left you—if—if—"

"Poor Ailie!" he strove to say, and his helpless hand tried to reach out towards her. "Who'll take care o' ye now, I wonder?"

"Father, don't go an' die," sobbed Ailie. "Mother's gone, too, and I'll have nobody—"

Jem Carter gave a heavy groan.

"Ah! Me—I little thought ever wife o' mine 'ud be a thief,—locked up in jail!" And a sob burst from the very heart of the dying man. "I'll never see her again. Ailie, mind ye tell her from me—"

The labouring voice ceased, and they listened in vain. The old woman had retired a few paces, but Esther Forsyth stood close beside the flock-bed, for Ailie was there, and her grasp on Esther's tattered gown was that of a vice.

"Tell her what?" asked Esther, after a minute of silence.

No reply came, and Ailie spoke timidly—

"Father, won't ye take a bit o' bread?"

"He's past eatin', child," said the old woman. "Let him die in peace, an' don't ye go to disturb him, if he'll do it quiet."

Some echo of the words seemed to reach the failing ear. He opened his eyes, and fixing them full on Esther, he muttered slowly—

"Die in peace! Die in peace! I'll never see Mary again. I'll be gone afore she's free. An' where will I be gone?"

It was an awful question, dropping from the ashen lips of that dying man, tottering upon the verge of a dark eternity. No answer came from his hearers—from the old woman, or from Esther Forsyth, or from poor little Ailie. What answer could they give? They hoped he would sink again into stupor, and "die quiet." But the hollow eyes looked from one to another in appeal.

"Where will I be gone?" repeated Jem. "I've nought to do with dyin' in peace—not I. What's them lines I once learned, or somebody telled me?—

"'There is a dreadful hell,

With darkness, fire, an' chains.'

"What's the rest, Ailie?"

"Oh, father, don't ye—don't ye," sobbed Ailie, in distress.

"Come, don't ye be in a taking, Carter," said Esther, trying to cheer him. "You've been a steady man enough, off an' on, and it's little o' drink that's passed your lips o' late."

"Drink!" repeated Jem; and then a strange look passed over the face looking up into hers. "Maybe I've not drunk as much as some. Maybe I've wanted to live respectable, and couldn't manage it neither. Will that take me to heaven, woman?"

The question came almost fiercely from between his parted lips, through which the labouring breath passed to and fro.

"'Tis little we poor folks has to do with heaven," she said.

"It's little you know," responded Jem Carter. "Wasn't it the poor, an' not the rich—somebody said. But I minds nothin' now. It's all gone. An' there's no one to say a word—an' I'm dyin'."

"Can't ye tell him what he wants?" sobbed Ailie.

"Can't nobody tell?"

"Can't nobody tell?" echoed the dry failing lips. "Mrs. Forsyth, can ye mind nothin' o' what I once heard?"

"I didn't know ye then," she said, with an effort to rack her memory for some dim recollection of the "sweet story of old," with which in childhood she had not been wholly unfamiliar. But it would not come. "There's nobody here as knows nothin'."

Nobody! Not one to bring a ray of light into the deep darkness of that poor benighted soul. Not one to hold the cup of life to those dying lips.

Awhile they kept silence, broken only by the deep breathing from the flock-bed. The old woman fidgeted about, and muttered to herself. Esther stood still, with the child clinging to her dress.

"He'll die easy now," she whispered encouragingly, and she hoped it might be so. But the closed eyes opened again, and wandered to and fro distressfully; and the word "Parson" was whispered more than once.

"An' where be we to find a parson?" the old woman demanded in her ignorance. "Likely a parson 'ud come to this hole, at this time o' night. Tell ye what, Mrs. Forsyth, if ye'll stay here a bit, I'll go an' settle off my old man, an' then come back an' stay, so as ye can go. 'Tain't fair to leave him alone like this, and ye'll have enough to do wi' your own six brats."

The proposition, though rough, was kindly. Esther made no objection, but only stood, after the old woman's departure, looking down fixedly as before upon the occupant of the flock-bed. There was a stirring of old memories in her mind. They had not answered to the call when she sought for them, but somehow they were working now. She hardly knew what impulse made her say bluntly, as she marked the knitted brows—

"Why don't ye pray, if ye're so fearsome?"

"Who be I to pray to?" demanded Jem. "I tell you I knows nought of such things."

"There was a thief as didn't know more," said Esther, uncertainly.

"I'm not a thief. I'm an honest man. I've prided myself all my life on bein' an honest man." Jem broke off there, with a sigh, at the thought of his wife. "'Tain't honesty as 'll take me to heaven, though; I knows that plain enough. Tell about the thief; I'd like to hear."

"I've forgotten nigh all. 'Twas old granny as used to tell me, when I was a slip of a child, an' she'd show me the pictures in her big Bible, but it's 'most gone from me now. I only knows it was a thief, an' he was a-dyin', an' he prayed—leastways he says a few words—'Lord, remember me when Thou comest'—I don't remember no more. 'Comest' somewhere; I've forgot."

"An' you can't remember it?" asked Jem despondingly. "Maybe I might say the words, if I knowed 'em. But I ain't a thief; I never was. Who was it he said the words to?"

"Why, Him as died same time, somehow," said Esther, with reluctance. "I tell you I've forgot; only I know he said them words to Him—to Jesus, as was nailed upon a Cross, wasn't He?"

Very doubtfully, and somewhat shamefacedly, too, she spoke; but like a strain of sweet music fell the sound of that holy Name upon the ears of the dying man. "Why," he said, with sudden energy, "'twas He, sure, as said that about the poor an' not the rich, somebody once telled me. Go on quick, woman."

Esther fidgeted with the edges of her tattered gown. "It's pretty nigh all gone from me," she said; "only I know He somehow telled the thief as he was to go straight to heaven that day."

"The thief was to?"

"Yes, the thief," repeated Esther. "And he hadn't done more than that bit of a prayer, neither."

"Maybe I wouldn't be heard if I was to ask too," muttered Jem.

Esther looked round involuntarily round at the dark abode of misery. This dreary cellar—was it possible that a dying prayer, uttered in such a place, could by any possibility ascend upwards—could escape through all the damp, and dirt, and oppression which weighed upon the very air—could pass onwards, higher and higher, to the pure blue sky far above the great city's wretchedness—could rise yet farther upwards till it reached the throne of God Himself? Esther did not put the question in words, but she felt something like it, and shook her head.

"Maybe not. We haven't much to do with prayin' hereabouts," she said bitterly. "I've nigh forgotten the meanin' o' the word."

Seemingly passing into stupor, Jem Carter lay, his hand flung out on the torn carpet which formed his covering. Presently the old woman came back, and, seeing that there was nothing more to be done, Esther took her departure. The old woman settled herself down on a little heap of rags in one corner, and was soon nodding and rocking drowsily. Ailie crept to her habitual resting-place at the foot of the flock-bed, and there, wearied out, she dropped asleep.

Was it night when she awoke? She sat up, and rubbed her eyes. Yes, darkness still, except for the fitful flashes of the half-expiring candle, with its unsnuffed wick. The broken back of the chair, on which it stood, was reflected in huge bars of shadow against the walls. Ailie watched them as they moved to and fro, and then she glanced at her father's face. How ghastly it looked, lying back on the bundle of rags which served for a pillow, while one bony hand was folded over the other. Ailie sat more upright.

"Father, father," she whispered. Was he living still?

She did not venture to speak aloud. The midnight silence was broken sharply by the step and voice of a drunken man, reeling along outside the window. Ailie shivered at the sound. She could see the old woman across the cellar, not nodding now, but fast asleep, her gray head leaning against the damp wall. Ailie dared not rouse her, but watched her father's face in aching fear; and all at once, he opened his eyes.

Dull eyes they were, yet they recognized his little girl, and she whispered "Father!"

"I ain't a thief, Ailie, but maybe He'd hear me," said Jem.

"I'd try," said Ailie.

Jem Carter looked up, glanced round, gazed at the bare floor, the bare walls, the bare ceiling. "There's nobody to speak to," he said. "Ailie, can't ye do it for me?"

Ailie did not need to ask his meaning; she understood it as well as he did himself. She had never been taught to kneel and clasp her hands in prayer, like so many happier little ones; but, after a moment's hesitation, she folded her arms together, looked into the darkest corner of the cellar, and said in a frightened undertone:

"Please remember father, like the thief. He wants it ever so much. Please don't forget father. Please do remember him.

"Will that do, father?" asked Ailie.

"Please, Lord, remember me when Thou comest," muttered Jem Carter after her. "There's nobody else to help. Please have mercy, Jesus, that was nailed up on a Cross. I don't know nothin' more about it."

And once more Ailie chimed in earnestly, "Oh, please do remember father.

"Don't you think He will now, father? 'Cause the thief didn't only ask Him once, an' we've done it three times. Don't you think He won't forget you now, father?"

Was there a smile on the dying face? Ailie thought so. But nothing more was said, and he seemed to fall asleep. Ailie, too, sank off again, and did not wake a second time till daylight was creeping in through the window.

The old woman was the first to rouse herself. She shook her limbs, grumbled at her hard couch, rose with difficulty, and walked across the cellar.

There on the flock-bed lay Jem Carter—silent, motionless, with closed eyes, and powerless hands. And there across his feet lay little Ailie, with one arm thrown under her head, and a troubled look in her childish face. Poor little fatherless Ailie!

Yes, he was dead! Untended and unwatched, he had passed away from his cellar-home. But the one faint cry to the Saviour of the world, out of the depths of his darkness, was surely not unheard, and poor Jem Carter, in his last extremity, was surely not "forgotten."

CHAPTER IV.

WHAT TO DO WITH AILIE?

SOMEWHAT late the following evening, John Forsyth walked into his room, and sat down at the table. Esther opened her lips to speak, but shut them again hastily, as she noted his moody expression. He glanced at the younger children, huddled in a heap upon the floor, and frowned at the sight of Ailie Carter, curled up asleep in a corner, Lettie being seated by her side, as if keeping guard over the forlorn little stranger.

"What's that child here for?" he demanded.

"She's got nowhere else to go to," responded Esther.

"Got no supper for me, I s'pose," said John gruffly.

Esther went to the cupboard, and brought thence a hunch of bread and a lump of cheese. John disposed of them both in silence, with the expedition of a man who has not broken fast for many hours.

"How did you get it?" he asked shortly, pushing aside the cracked plate.

"Hor earned a shillin' with runnin' of errands and doing jobs. I've give the children some, and there's some over for to-morrow. It won't do to eat up all, John," as she detected a hungry gleam in his eyes.

"An' there be the rent as well," said John despondingly. "You've been a-giving more to that there child, Esther."

"Would ye wish to see her starvin' afore our faces?" asked Esther. "What of her mother?"

"Two months in jail," said John laconically. "Went to the station-house myself, an' heard it all. There was a deal o' talk, an' one man he wanted to make out as she was a hardened offender, but that wouldn't stand. She hadn't never been in trouble before, she said, and they found it was true, leastways they couldn't find no proof to the contrary. She pleaded guilty to taking the loaf, but wouldn't agree to the purse—she didn't know why she touched it at all, and she was certain sure she had never meant to take it. There was a laugh at that, an' 'twas easy to see no one believed the poor thing. She sobbed a bit, when they first brought her up, but after that she stood quiet, an' they said—one on 'em—that she was sullen, and he didn't believe as it was her first offence."

"She were as honest as the day till then," said Esther.

"They couldn't tell that, an' they didn't know how she had been nigh crazed by all she had borne. 'Twasn't done in her sober senses, I do believe. There was a long tale made out o' the purse, an' the lady wanted to prove as there was an accomplice as called off her attention, so as Mrs. Carter might whisk it off the counter where it was laid; but nobody hadn't seen no accomplice, unless 'twas little Ailie, an' when some one spoke o' the child, the poor thing called out quite indignant, an' seemed as if she couldn't bear the thought. They questioned her more then, an' she answered steady and sensible, that she had never thought what she was going to do, but she'd sold all she had, an' walked about all day a-huntin' for work, and she and her child was half-starved, an' her husband a-dyin'.

"'Aye, an' he's died in the night, has poor Jem Carter,' says I, speakin' up loud, 'died for want o' the food which none o' you gentlemen knows what it is to be without.'

"They did look shocked at that, all of 'em, an' Mrs. Carter, she gave a little cry, an' turned white-like. They was sorry for her, all on 'em. I could see that plain enough, and they didn't talk no more of puttin' off her trial to the Quarter Sessions, which was the thing as she had seemed to dread most. Some wouldn't have give her more than a month, I fancy, but one old gentleman, he muttered out that people couldn't be let steal, if they was starvin', and examples must be made.

"Mrs. Carter seemed like one nigh stupid, an' never lifted her head, not even when they told her her punishment. And the lady, whose purse it was she took, came near to crying, and said she wished the poor thing could ha' been let off altogether—she was so sorry for her, left a widow alone like that."

"An' how ye could go and tell her all of a sudden!" said Esther, reproachfully.

"I didn't think when I spoke, and it did good too, for they'd ha' given her longer imprisonment but for that. 'Twas her being caught, ye see, with the loaf in one hand, an' the purse in the other, which made so much o' the matter, an' she wouldn't plead guilty to the purse—she didn't scarce know she had touched it, she said, an' others declared she was a-carryin' it off. An' what do they know of the home and the misery as drove her to it?" said John bitterly. "I've felt nigh bein' driv to something desperate myself, before now of late. Anyway she's caged up now for two months, till fourth o' November. That child ain't going to stay here, Esther."

"Where be she to go?" asked Esther in a compassionate tone.

"She ain't a-going to stay here," repeated John, doggedly. "I've give way once, as ye know, to takin' in other folks' children—no need to go into that now. I never grumbles at what's done, and I loves her now like to my own; but I ain't a-going to do it a second time. We've enough an' to spare of our own."

"What'll we do with her?" asked Esther.

"There's the work'us," said John. "I'll take her there myself to-morrow. Ye needn't say a word against it."

"And her poor mother, as prided herself on never takin' a grain of help from the parish," said Esther.

"She must take the consequence o' her own deed," said John, somewhat less indulgent towards her himself, than he had perhaps expected the magistrates to be. "Starvin' or no starvin', 'twas stealin', and she must put up with the consequence. There's no one left as belongs to the child, an' to the work'us she'll go."

Ailie never moved or spoke, but she was not asleep. Every word had fallen on her ears like a blow. Mother in prison for two months—two whole months. O what a long time it seemed to poor little Ailie! She could scarcely have felt more hopeless at the prospect of two years' separation. And then to be sent away herself—away to the workhouse—away, all alone; among utter strangers. She had been brought up with such a horror of the workhouse; prison itself sounded hardly worse to her. Not that she knew anything about what kind of a place it was, except that her mother's one great dread for months past, and her father's too, had been that of "coming to the workhouse." What would mother think of her being there? Poor Ailie forgot or did not understand that the lesser disgrace of dependence on the parish would be swallowed up in the far deeper disgrace of trial and imprisonment for theft.

Worst of all to Ailie was the thought of her mother coming home at the far-off end of those two months, and finding her child gone. What if she didn't know where to go, and never found Ailie, and Ailie never saw her again! Ailie cried silently at the thought. She could not, could not go. She must wait here for mother; she would be a trouble to no one, and eat so little, and sleep anywhere, and creep into corners—only she couldn't go away.

How to avoid it, Ailie did not know. At first she thought she would beg John Forsyth to change his mind, but when she opened her eyes softly and peeped at him, he looked so moody that she dared not speak. Then she thought that she would slip off, and hide herself in some dark secret place, until—oh, until there was hope that they might change their minds. She knew of many a hole and corner in the old rambling house, but to escape at present, without remark, was impossible, and she determined to bide her time.

What was to be done with her this night she did not know; neither did Esther. There was certainly no vacant space for her in the overcrowded apartment. A young widow living in the next room, with only three small children of her own, offered to take in Ailie, much to the relief of all parties. She slept there quietly on her heap of straw, and shared the children's scanty breakfast; but, after that, she watched for the first opportunity to slip unobserved out of the room, and to run down-stairs.

What she meant to do with herself Ailie had no very clear idea. Her one aim was to escape from John Forsyth, in dread of being walked off to the workhouse. A house of terror it was to her, in truth, and her greatest terror of all was the childish dread that if she once went away her mother would never find her again. Her one wish now was to be where John Forsyth could not discover her. The old court at the back of the house would not do. He would naturally look for her there, among the crowd of neglected little ones who spent hours every day in playing and quarrelling together over the mud, stones, and old oyster-shells there to be found. She dared not be seen on the staircase or in the passages. He might walk down any one of them. She would not loiter about in the street, for he would be sure to pass there.

Creeping at length into a dark corner, under the pile of lumber, refuse, and ruin which blocked up the empty space under the staircase, she settled herself into as easy a position as possible, and there decided to remain. They were not likely to seek for her in such a spot.

She congratulated herself not a little on her hiding-place, half an hour later, when she heard a heavy step coming down over her head, and John Forsyth's voice demanding, in evident annoyance—

"I say, can any o' you tell me what's become o' Carter's little girl?"

"Ailie Carter," croaked the old woman who had kept watch by her dying father's side. "No, not I. Where have she been all night?"

"Sleepin' with Mrs. Crane. If I catch her, she shan't forget the trouble she's a-giving us—running away and a-hindering like this! But I can't wait in no longer. If she thinks she's going to live on us, she's mistaken."

He went away grumbling, and Ailie did not breathe freely till he was out of hearing. She dared not let herself be seen even then, though aware that he would now be absent for hours on the search for work. If found, she would doubtless be watched till he returned, and then taken off to the workhouse. Ailie had set her whole heart upon not going there. She sat on resolutely in her dark close corner—hungry, cramped, and miserable, but enduring all, hour after hour, with a steadfast patience, unknown to more tenderly-nurtured children. It was nothing unusual to her to fast during a whole day.

But time passed slowly, and Ailie grew wretched and forlorn, as the hours went on. She slept a good deal, and listened to what went on overhead, and sometimes cried quietly; but she never thought of giving way, and coming out. She would do or bear anything in her power to escape going to the workhouse. She must wait for mother—poor mother, away in jail! Ailie longed so to see her again.

And poor father, too—not twenty-four hours dead. Ailie's little heart swelled and ached at the thought of him, and of that short midnight waking, which seemed now so very far away. How she wondered if the story told by Esther had come true, and if he had been remembered—by—Ailie did not exactly know whom. She had been brought up in such utter ignorance, that she knew scarcely more than the Name of God. She had never heard the Name of Jesus till it fell from the lips of Esther in her hearing.

Still, she knew her father had feared something, had wanted something, had asked to be remembered by some one, and she wondered much if he had had his wish, and how he could have had it. Ailie wished some one would remember her. Not the Forsyths; she only wanted to keep out of their way. But some rich kind person—if such a person would come and look after poor little Ailie, and give her plenty to eat, and let her stay where she was till mother came back, and give her a clean frock, instead of these rags—oh, how nice it would be!

Not much hope of all that, but it soothed Ailie to sit and fancy it. It made her forget her hunger and thirst for a while. And, in the middle of her fancying, she fell asleep, and dreamt that little Lettie came running up, and took her by the hand to lead her away. Ailie was frightened at first, and tried to draw back, but Lettie pulled her forward, and then took her a long walk, through many streets, till Ailie was footsore and weary, and wanted to rest. But all at once they stood before a door, which somebody opened, and Ailie found herself in a bright room, with nicely-dressed ladies smiling on her, and a long table covered with tea and bread and butter and cake. And then, just as a great plateful was set before Ailie, and she was going to begin to eat, the table and the ladies and the room faded away, and Ailie woke to find herself in her dark dusty corner, more hungry than ever.

How bitterly poor Ailie sobbed to herself, and how she did wish that she had slept a little longer, so that she might at least have dreamt that her hunger was satisfied!

CHAPTER V.

STARVING.

"HOR," said little Lettie meditatively, on the afternoon of the following day, "don't you wonder what's become of Ailie?"

Hor had just returned from his daily ramble in search of employment. Little hope had he now of finding regular work—he had tried so long in vain; but still he contrived to earn a few pence in various ways, and those who had once employed him did not soon forget his honest look. To-day he had returned earlier than usual, and, after depositing his earnings with his mother, went out into the yard. There he found Lettie, seated on a corner of the broken-down wall, overlooking the three little ones, who made high glee with a mud puddle near at hand.

"Mother says nothin' more ain't been seen of her," said Hor. "Queerest thing I ever heard of. Seems as if some'at wrong must have happened to the poor little lass."

"Father was askin' about her this mornin'," said Lettie. "He says he can't do no more. Mother thinks some one must ha' taken her off."

"Don't seem much sense in that, neither," said Hor. "She hadn't on a scrap o' clothes as would fetch sixpence. More likely—well, I don't know—but maybe it's a fancy o' the little thing herself. P'raps she's gone off, thinkin' she'll find her mother. I shouldn't wonder."

"Hor," said Lettie deliberately, "Ailie wasn't asleep, but only pretendin', when father talked o' the work'us for her."

"Wasn't she?" cried Hor.

"I'm sure I see her open one eye, an' shut it up again tight; an' she was cryin' after, when you all thought she was a-sleepin'."