Too Dearly Bought: Or The Town Strike

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

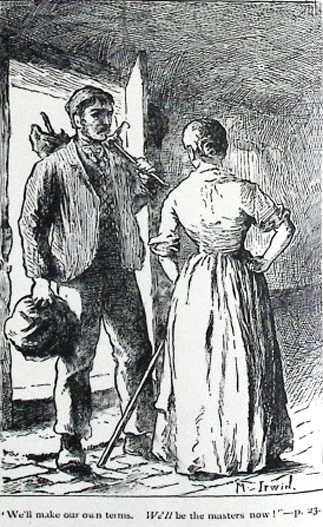

"We'll make our own terms. We'll be the masters now!"

TOO DEARLY BOUGHT

OR

THE TOWN STRIKE.

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF

"HIS ADOPTED DAUGHTER," "THE OLD HOUSE IN THE CITY,"

"WILL FOSTER OF THE FERRY," "MADGE HARDWICKE,"

ETC.

With Illustrations.

LONDON:

JOHN F. SHAW AND CO.

48, PATERNOSTER ROW, E. C.

STORIES BY AGNES GIBERNE.

IDA'S SECRET; or, The Towers of Ickledale.

Cr. 8vo, 2/6.

WON AT LAST; or, Mrs. Briscoe's Nephews.

Cr. 8vo, 2/6.

"The treatment is so admirable we can understand Miss Giberne's book being a help to many."—Athenæum.

HIS ADOPTED DAUGHTER; or, A Quiet Valley.

Large Cr. 8vo, 5/—.

"A thoroughly interesting and good book."—Birmingham Post.

THE EARLS OF THE VILLAGE.

Large Cr. 8vo, 2/6.

"A pathetic tale of country life, in which the fortunes of a family are followed out with a skill that never fails to interest."—Scotsman.

THE OLD HOUSE IN THE CITY; or, Not Forsaken.

Crown 8vo, cloth, 2/6.

"An admirable book for girls."—Teachers' Aid.

FLOSS SILVERTHORN; or, The Master's Little Hand-maid.

Cr. 8vo, 2/6.

"We should like to see this in every home library."—The News.

MADGE HARDWICKE; or, The Mists of the Valley.

Cr. 8vo, 2/6.

"An extremely interesting book, and one that can be read with profit by all."—The Schoolmaster.

WILL FOSTER OF THE FERRY.

Cr. 8vo, 2/6.

"We are glad to see this capital story in a new shape."—Record.

TOO DEARLY BOUGHT.

Cr. 8vo, 1/6.

"A timely story, which should be widely circulated."

LONDON: JOHN F. SHAW & CO., 48, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

CONTENTS.

CHAP.

I. FLAGS AND BANNERS

II. PETER POPE'S SPEECH

III. THE STRIKE BEGUN

IV. WHAT STUCKEY THOUGHT

V. DUCKED

VI. SEED-CAKE

VII. THE CHILDREN

VIII. HOLDFAST'S SPEECH

IX. A COLD EVENING

X. THE QUEER LOOK OF THINGS

XI. BABY HARRY

XII. ANOTHER MEETING

XIII. A DISCUSSION

XIV. HOW IT ALL ENDED

TOO DEARLY BOUGHT

OR

THE TOWN STRIKE.

CHAPTER I.

FLAGS AND BANNERS.

THE procession was coming down Pleasant Lane!

A great number of noisy little boys came trooping on ahead, with shrill cries, to announce this important fact. Hardly one among them understood exactly what the procession was about; but flags and banners are the delight of a boy's heart. Not seldom this particular form of affection for coloured bunting lasts on into manhood.

The wives and mothers, who turned out of their doorways to enjoy the sight, were, however, more learned than their little boys as to the cause of the stir. And everybody was aware that Peter Pope was to be at its head.

Peter Pope, a smooth-tongued and comfortably-dressed individual, had been very busy lately in the town. Most of his business had been in the way of talk; but what of that? There was a committee, of course, behind him, which did a good deal of work while Pope did the talk. He had been sent down, as a delegate from London, for the express purpose of teaching the inhabitants of the town; and teaching commonly means a certain amount of talk. Peter Pope had come to teach the men of the town to appreciate their degraded and enslaved condition. With this object in view he had talked vigorously for many weeks; and the men were becoming fast convinced of the truth of his words. They had not dreamt before what a melancholy thing it was to be a British working-man; but now their eyes were opened.

If you want to convince the British Public about anything,—especially that part of the British Public which reads very few books, and knows very little of history, and never goes out of England, just remember this! There is not the least need that you should be clever or learned yourself, or even powerful in speech. You only have to go on saying the same thing over and over and over again, with dogged pertinacity; and in time you are sure to be believed. The British Public is wonderfully easy of belief, and will swallow anything,—if only you give it time! Peter Pope had done this. He had talked on, with a resolute and dogged pertinacity; he had given his hearers plenty of time; and now he was rewarded by seeing the biggest boluses he could offer, meekly gulped down.

It was a dingy and smoky town enough to which he had come; one of the crowded manufacturing towns, of which England owns so many. Not a clean or pretty town, but a prosperous one hitherto, with a fair abundance of work for willing toilers. Those who were unwilling to toil did badly there as elsewhere; and these were the men who first swallowed Peter Pope's bait.

Pleasant Lane was not the least narrow and dingy of many narrow dingy streets. The houses on either side were small, and for the most part not over clean. One little home near the centre formed a marked exception as to this last point; boasting dainty muslin blinds, windows filled with plants, and a spotless front doorstep.

On that step stood Sarah Holdfast, in her clean print gown, watching like others for the coming procession. Not that she had the least idea of seeing her husband figure in it. She was only dandling her baby, and lifting it up to be amused with the stir.

Martha Stevens, a young and pretty woman in the next doorway, had no such security about her husband. Roger Stevens was morally sure to be in the thick of whatever might be stirring,—whether it were good or bad. He was a well-meaning man, and not usually unsteady; but, like a good many of his companions, he was easily led, always ready to believe what he was told, and ever prepared to follow the crowd. As the stream of public opinion—the public opinion of the little world around himself—happened just then to run in the direction of a grand procession, Martha had not a shadow of doubt that her husband would find his place somewhere in the said procession.

"What's it all about, mother?" asked Robert, a rosy child of nine.

"It's the men, Bobbie," she said. "They're having a procession."

"What for?" asked Bobbie.

"They want something that the masters won't give 'em. They want higher wages and shorter hours."

"But what's the 'cession for?" persisted Bobbie.

"I'll tell you what it's for," volunteered a slovenly woman in the left-hand doorway, tossing a ragged infant in her arms. "It's to show that they're Men, and they're going to have their Rights! Time enough too! Working-men ain't a-going to be trampled on no longer, nor their wives neither. We won't put up with no more tyranny nor nonsense."

Martha moved her head from one side to the other, and was silent.

But Sarah Holdfast remarked dryly, "There's a sort of tyranny in the home that isn't so easy got rid of! And there's a tyranny of working-man to working-man, which I'd like to see done away with. It may be harder tyranny than the tyranny of capital, which folks talk such a lot about nowadays."

"Oh, you! I dare say—you're sure to say that!" the untidy woman retorted with contempt. "Your husband's such a poor-spirited chap—all on the side of the masters."

"He is not on the side of the masters," Sarah answered resolutely. "He's on the side of doing what is right; and he's against tyranny of every sort,—it don't matter whether it's tyranny of masters or of men. That's what the lot of you don't and won't see."

"Here it comes!" cried Bobbie.

Except to a young imagination such as Bobbie's, the advancing procession was not perhaps very imposing; but it made a good show in point of numbers, and the men kept well together, in a solid and orderly phalanx. Outside the main body walked detached individuals, carrying money-boxes; for the processioners had a practical object in view beside the mere display of numbers. They would not only march round the town, endeavour to impress the imaginations of people generally, and pay a visit to their employers' office to make formal demand of what they required, but also they hoped to gather funds by the way for the coming struggle. Most of the men appeared thus far to be sober; but some towards the rear showed signs of a recent visit to a public-house.

At the head of the procession marched a brass band, playing lively jigs, very much out of tune; and the amount of flags and banners following was really quite respectable.

First might be seen a great sheet of white calico, stretched across two poles, and bearing the portentous inscription—

"WE DEMAND FIFTEEN PER CENT. AND EIGHT HOURS."

Next swaggered unsteadily along a second white calico sheet, with the words—

"UNION IS STRENGTH!"

An axiom so self-evident that nobody could question its truth.

An "Oddfellows" banner, drooping gracefully from its single pole, came next. It had a picture of the good Samaritan on a blue ground, and was not peculiarly appropriate to a strike; but flags of all kinds help to swell the general effect, and this with others was borrowed.

After the good Samaritan, a loaf stuck upon a pole was borne along. No especial meaning might be attached to the uplifted loaf; but no doubt bread is always an impressive object. What would man be without the "staff of life"? There is also an obvious connection between loaves and wages.

At the tail of the procession, after sundry other appropriate and inappropriate flags, made or borrowed, came the final output of native genius—another big square of white, having its inscription painted with a tar-brush—

"WE MEAN TO GET OUR RIGHTS!"

This sentiment began with a magnificent "W," and tapered gradually off to an absurdly diminutive "s"; no doubt the natural expression of artistic feeling.

A loose crowd of open-mouthed followers clattered along behind, deeply impressed by the whole affair.

"It's a grand lot of flags, mother, ain't it?" said Bobbie.

Martha was gazing, as if she did not hear, and little fair-haired Millie said, "Daddy's there!"

One look in the direction where the tiny hand pointed, and Martha turned away.

"Come, Millie,—come, Bobbie,—we'll go indoors now."

"O mother, I want to wait," cried Bobbie. But he yielded to her touch and went in, only asking eagerly—"'Why mayn't we stay?"

Martha made no answer. How could she bear to tell her child that his father had been drinking?

CHAPTER II.

PETER POPE'S SPEECH.

"TELL ye what, boys; now's the time! Now's the time if ye want to gain your freedom! If ye give in tamely now and let yourselves be driven to the shambles like a flock of silly sheep, and crushed to the earth under the iron heels of a set of despots, as 'ud grind down the very souls of ye, if they could, into scrapings of gold-dust,—why, ye'll never hold the position of men!"

Peter Pope had taken his stand at the corner of a street one evening, two or three days after the grand procession. He mounted a block of wood which lay conveniently there; and being thus raised over the heads of his compeers, was at once in a situation to exercise power over their minds. Men began to gather round him, with attentive eyes and ears, ready to believe whatever Peter Pope might assert. Englishmen do not often put faith in Roman infallibility; but give an English Pope to a particular class, and no amount of infallibility becomes impossible.

"Now's the time!" pursued the orator, flourishing his arms, "now's the time! It'll maybe never come to ye again. There's a good old saying, lads, as tells us 'Procrastination is the thief of time!' Procrastination means putting off. Procrastination is putting off the settling of a question like you're doing now. Procrastination is the thief of time. It steals time! It steals the nick of time, when the nick of time comes; and once gone, you'll never get that nick of time back."

"Now's the time I tell ye, boys! Will you cringe before the iron heel of capital? Will ye knuckle down before the bloodhounds of tyrannic power, when ye may fight and conquer, if ye will; and come out from the battle men, and not slaves?"

"For you're not men now!—Don't think it. Men!—When ye have to work like dogs for your living! Men!—When you're counted plebeians by them as 'll scarce deign to look at ye in passing. I tell ye, lads, ye're all tied hand and foot; though many a one of you scarce feels his bonds, just because he don't know what freedom is. You're degraded and miserable and enslaved, and don't scarce know what it is to wish for anything better."

"That's what I've come down to you for, my men. It's because I want you all to see what you are, and what you might be, if ye'd sense and spirit to exert yourselves. It's because I'm a friend of the Working-man. It's because the noble society, of which I am a member and a delegate—and proud to be both;—it's because that noble society is the friend of the Working-man, desirous to rescue him from the gigantic heel of a merciless power, which is crushing him in the dust—like the boa-constrictor, lads, which wraps the victim in its voluminous folds, and slays him in its slimy embrace. And the best thing a friend can give is advice. Advice, men. Wise advice; thoughtful advice; advice founded on knowledge, which 'tisn't everybody has power to attain to."

"What are we to do first? That's what you'll say; that's the question ye'll put. Don't I read it now in your manly faces, lads, all a-looking up at me this moment? And I'll tell you what you're to do first! You're to—"

"UNITE!!"

The word came out with tremendous emphasis, emitted by the whole force of Peter Pope's lungs, after a suitable pause. It made a proportionate impression.

"Ye'll say, 'What for?' To show your power, lads; to show that ye won't be cajoled, nor cheated, nor beaten down, nor taken in, nor treated like a pack of infants. And then you're to—"

"STRIKE!! That's the word for you, men. It's a mighty easy word. It's a mighty easy thing. Just strike—and the business is done."

"What business?" a voice asked.

"What business? Why, the business of getting what you want. You want shorter hours and an increase of fifteen per cent. on your wages, eh? Just so. You've made the demand in fair and reasonable terms, eh? Just so. You're freeborn Englishmen, all of you, eh? Just so—or had ought to be. What man living has a right to say you're not to have a rise which is your fair and just due? Why, if it wasn't for the tyranny of capital, you'd have had it months ago."

"Will ye submit to that tyranny? Will ye let your children grow up under that tyranny? Tell you, lads, it's time to make a change. Things have gone on long enough. It's time you should be the masters now! Show yourselves men, lads. Better to die than to yield. Give a cheer with me, now! Hurrah for the strike! Hurrah! Hurrah for the strike! Hurrah for the strike, boys!"

They went a little mad, of course, and shouted and yelled in chorus, not musically, but to Peter Pope's satisfaction. Peter Pope's enthusiasm was catching, and so was the toss of his cap. What "boys" would not have followed his example, under like circumstances?—"Boys" of any age. There is no great difference, after all, between the credulity, or to use a certain working-man's forcible word, the "gullibility," of young and old and middle-aged.

Somewhere near the outskirts of the crowd stood a man, in age verging perhaps on fifty, or even fifty-five. He was little and crooked in figure, with a wizened face, and glittering eyes under bent overhanging brows. Everybody knew Peter Stuckey; the man-servant of the Rector of the neighbouring church—gardener, groom and coachman, all in one. Years before, Mr. Hughes had taken Peter Stuckey into his service, after the severe accident which cut the man off from his old work. Peter did his utmost to repay with personal devotion this disinterested act.

Through his namesake's oration, he stood with his head on one side, and a note-book in his hand, scribbling a word occasionally. After the uproar of cheering, Stuckey turned to a sensible-looking man near, who had been as silent as himself, and dryly remarked—

"I say, we've learnt a deal this evening."

"H'm," the other answered.

"Such a lot o' facts, I've had to note 'em down for fear of forgetting. Let's see—"

"'Working-men are like sheep.' Some truth in that. I've heard say as how if one sheep jumps over a broomstick, all the rest 'll follow to save walking round it."

"The aristocracy is 'bloated.' Don't see much meanin' in the term; but, howsoever, it looks grand, so we'll let it pass."

"'Men are not men, but has to work like dogs.' Shouldn't wonder. Little enough o' work Rover gets through in the twenty-four hours—and little enough many o' them get through. But he does a deal o' barking."

"'Peter Pope yonder is a friend o' the working-man.' Werry disinterested friend!"

Stuckey paused, and gave a side-glance at his companion.

"Well, I won't go for to say whether Peter Pope or Peter Stuckey is the wiser man o' the two; but I won't go for to say I haven't a notion. Any way he's uncommon like to his namesake of Rome, layin' down the law for everybody."

"There's nothing on earth that can't be made out in the way of talk," the other said briefly.

"You're a sensible fellow, Holdfast, and no mistake. Now what's your opinion about this here notion of a strike?" asked Stuckey, putting one hand up to his mouth with a confidential air.

"I'll not move in the matter. But it'll come about without me," Holdfast replied, wearing the look of one who sees impending evil.

"Trust Pope for that; he'd be a loser if it didn't. They'd every man Jack of 'em put his head into a noose if Pope told 'em it was right. Well—an' I've got to be off," said Stuckey, as a fresh burst of shouts arose.

He lingered till it ceased, then singled out a man standing near—

"I say, Stevens; you and the rest is hearing a lot o' rayther startling assertions. If you'll take a bit o' friendly 'adwice,' you'll just ask Mr. Pope a question from me. Which is—how much that there Society pays him for the making of his grand speeches?"

Stuckey's voice was very distinct. Peter Pope had to defer the winding-up of his oration a full quarter of an hour, that he might do away with the effect of Stuckey's parting suggestion.

CHAPTER III.

THE STRIKE BEGUN.

"THERE!" said Roger Stevens, setting down his bag of tools, with the air of a man who has done a noble deed, and is aware of the same.

Martha's lips parted, then closed fast. She stood looking without a word.

"Nobody'll dare say now that we're to be trodden on like reptiles," continued Stevens loftily.

"Who ever did say it?" asked Martha.

"Well, Pope said they might; and they won't be able now."

"Then the strike's begun, and it's all up!" faltered the wife.

"All up! It's all just begun! There's thousands out to-day, and there 'll be a thousand more to-morrow. The masters won't stand that long. We'll make our own terms. We'll be the masters now!!"

"Mr. Pope says so, I s'pose," murmured Martha.

"And good reason he has to say it too. I tell you, he knows what he's about. 'Tain't often you come across a cleverer chap than Pope."

"I wish he'd kept himself and his cleverness away! I've a notion he wouldn't be so ready for the strike, if it was he that had to lose his living by it."

"Well, I never did in all my life see a woman like you—not a bit of spirit!" declared Stevens. "One 'ud think you cared for nothing in the world but food and drink."

"Why, it's food and drink you're striking for now, isn't it? Drink 'specially, and tobacco," said Martha; with tart truth. "Leastways, it's more money to get your drink and tobacco with."

"No, it isn't," returned Roger loudly. "It's because a rise is our due! It's for public spirit, and to show we won't be trampled on. That's what it's for. There's a lot of men gone out to-day who haven't got no particular grievances, and they're just striking for the principle of the thing—just for to help us."

"They'd be a deal wiser if they stayed in for the principle of the thing," said Martha.

"You've not got a spark of spirit in you," grumbled Roger. "Look at Mrs. Hicks! She don't hold her husband back. She's been pushing him on, and encouraging him from the first to act like a man."

"Mrs. Hicks may, but Mrs. Holdfast don't; and I'd a deal sooner be like Mrs. Holdfast."

Roger flung away impatiently out of the house; and Martha walked to the open door.

A busy street met her gaze,—busy, that is to say, as regarded the amount of moving life, not as regarded actual employment. The road was filled with scattered groups of working-men in their working-dress; some of whom wore looks of depression and anxiety, though the prevailing sensation seemed to be of triumph.

For the Strike was begun!

The masters could not long hold out. Success, speedy success, in the shape of higher wages and shorter hours, might be confidently expected. So Peter Pope declared. Capital could not but fail in a tussle with labour; for what was capital without labour? Peter Pope forgot to ask the equally forcible question—What was labour without capital? It is so easy to say, What is a man's head without his body?—But then one naturally inquires next, What is a man's body without his head? Unless the two work in harmony, both come to grief; and a wrong done by the one to the other always recoils upon itself. This is not more true of the joint existence, a man's head and body, than of that other joint existence, Labour and Capital.

Still, Peter Pope said things were all right; and who should know better than Peter Pope?

Those among the strikers who were members of a Trades Union felt comfortably sure of a certain amount of help, to carry them through the fight.

The larger proportion, who were not members of any such Union, indulged in vague hopes of being somehow or other tided through.

For the strikers belonged to more trades than one in the town; some having gone out, as Stevens implied, "on principle," or in sympathy with the rest.

Peter Pope was not far off. Martha could see him at a little distance, haranguing a group of listeners. She turned away with a sigh, and found Sarah Holdfast by her side.

"Stevens is one of them, I suppose," Mrs. Holdfast said kindly.

Martha tried to speak, and her voice was choked.

"Come, I'll go indoors for a minute. Baby is asleep, and Bessie's such a steady little lass, I may leave them just for a bit."

Martha was glad to get out of sight of that exultant crowd, looking to her foreboding sight so like a flock of thoughtless sheep, frisking to the slaughter. Peter Pope's illustration had not been inapt.

"How well the children do look, all of them!" said Mrs. Holdfast. "Just see Bobbie's cheeks! And I'm sure Baby Harry is a beauty. Hasn't he fat arms?"

"And how long are they going to keep fat, I wonder?" asked Martha.

Mrs. Holdfast hardly knew what to say. She stroked the head of little three years-old Harry, as he nestled up to his mother. Martha took such a pride in her children. They had hitherto rivalled Mrs. Holdfast's in healthy freshness.

"I'd work my fingers to the bone, if I could, to keep 'em as they are now," said Martha. "But whatever am I to do? I can't leave 'em alone all day, and go out to charing. I'm sure it's little enough work my husband does at the best of times; and now he's ready to risk starving us all, just that he may stick up for his 'rights' as he calls it. Rights indeed! It makes me sick to hear 'em all a-talking of their rights," cried Martha, with sudden energy, as she hugged little Harry in her arms. "A man's wife and children has a right to expect he'll give them food to eat, and clothes to wear; and if he won't do that, he'd no business to marry."

"Men are easy led to believe whatever they're told—provided it's one of themselves that tells them," said Mrs. Holdfast shrewdly.

"I don't see as that's any excuse. They'd ought to have sense to think for themselves."

"So they would, if they was all like my John," said Mrs. Holdfast, with pardonable pride. "But there's where it is. He reads and learns, while other folks talk."

Martha found no comfort in the thought of John Holdfast's superiority.

"See here—" she said, looking round—"all the little comforts we've been getting together, when we could spare a sixpence or a shilling. And they'll all go now. I won't say but what Roger's been a good husband in the main, letting alone that he's so easy led. He does care for the children, and he brings home his wages more regular than most—if he wasn't so fond of a day's holiday, when he ought to be at work. Talk of short hours! He's never in no danger of overdoing hisself. But that's the way with the men. I wonder whatever 'd happen if we women was to strike for short hours, and knock off work, and leave things to take care of themselves."

Mrs. Holdfast shook her head dubiously. She saw that it was a relief to Martha to pour out.

"I'm sure I've toiled day and night for him and children, and never wanted to complain. Roger has had a clean home, and his clothes mended, and his Sunday dinners as good as the best of them. And I'd just begun to think of laying by something against a rainy day. And here's the end of it all."