Korea and Her Neighbors

Isabella L. Bird

KOREA, AND HER NEIGHBORS

KOREA

And Her Neighbors

A Narrative of Travel, with

an Account of the Recent

Vicissitudes and Present

Position of the Country

By

Isabella Bird Bishop, F.R.G.S.

Author of “Unbeaten Tracks in Japan,” etc.

With a Preface by

Sir Walter C. Hillier, K.C.M.G.

Late British Consul-General for Korea

With Illustrations from Photographs by the Author,

and Maps, Appendixes and Index

New York Chicago Toronto

Fleming H. Revell Company

M DCCC XCVIII

Copyright 1897

BY

Fleming H. Revell Company

Preface.

I have been honored by Mrs. Bishop with an invitation to preface her book on Korea with a few introductory remarks.

Mrs. Bishop is too well-known as a traveler and a writer to require any introduction to the reading public, but I am glad to be afforded an opportunity of indorsing the conclusions she has arrived at after a long and intimate study of a people whose isolation during many centuries renders a description of their character, institutions and peculiarities, especially interesting at the present stage of their history.

Those who, like myself, have known Korea from its first opening to foreign intercourse will thoroughly appreciate the closeness of Mrs. Bishop’s observation, the accuracy of her facts, and the correctness of her inferences. The facilities enjoyed by her have been exceptional. She has been honored by the confidence and friendship of the King and the late Queen in a degree that has never before been accorded to any foreign traveler, and has had access to valuable sources of information placed at her disposal by the foreign community of Seoul, official, missionary, and mercantile; while her presence in the country during and subsequent to the war between China and Japan, of which Korea was, in the first instance, the stage, has furnished her the opportunity of recording with accuracy and impartiality many details of an episode in far Eastern history which have hitherto been clouded by misstatement and exaggeration. The hardships and difficulties encountered by Mrs. Bishop during her journeys into the interior of Korea have been lightly touched upon by herself; but those who know how great they were, admire the courage, patience and endurance that enabled her to overcome them.

It must be evident to all who know anything of Korea that a condition of tutelage, in some form or another, is now absolutely necessary to her existence as a nation. The nominal independence won for her by the force of Japanese arms is a privilege she is not fitted to enjoy while she continues to labor under the burden of an administration that is hopelessly and superlatively corrupt. The role of mentor and guide exercised by China, with that lofty indifference to local interests that characterizes her treatment of all her tributaries, was undertaken by Japan after the expulsion of the Chinese armies from Korea. The efforts of the Japanese to reform some of the most glaring abuses, though somewhat roughly applied, were undoubtedly earnest and genuine; but, as Mrs. Bishop has shown, experience was wanting, and one of the Japanese Agents did incalculable harm to his country’s cause by falling a victim to the spirit of intrigue which seems almost inseparable from the diplomacy of Orientals. Force of circumstances compelled Russia to take up the task begun by Japan, the King having appealed in his desperation to the Russian Representative for rescue from a terrorism which might well have cowed a stronger and a braver man. The most partial of critics will admit that the powerful influence which the presence of the King in the house of their Representative might have enabled the Russian Government to exert has been exercised through their Minister with almost disappointing moderation. Nevertheless, through the instrumentality of Mr. M’Leavy Brown, LL.D., head of the Korean Customs and Financial Adviser to the Government, an Englishman whose great ability as an organizer and administrator is recognized by all residents in the farther East, the finances of the country have been placed in a condition of equilibrium that has never before existed; while numerous other reforms have been carried out by Mr. Brown and others with the cordial support and co-operation of the Russian Minister, irrespective of the nationality of the agent employed.

Much, however, still remains to be done; and the only hope of advance in the direction of progress—initiated, it is only fair to remember, by Japan, and continued under Russian auspices—is to maintain an iron grip, which the Russian Agents, so far, have been more careful than their Japanese predecessors to conceal beneath a velvet glove. The condition of Korean settlers in Russian territory described by Mrs. Bishop shows how capable these people are of improving their condition under wise and paternal rule; and, setting all political considerations aside, there can be no doubt that the prosperity of the people and their general comfort and happiness would be immensely advanced under an extension of this patronage by one or other civilized Power. Without some form of patronage or control, call it by what name we will, a lapse into the old groove of oppression, extortion, and its concomitant miseries, is inevitable.

Mrs. Bishop’s remarks on missionary work in China and Korea, based, as they are, on personal and sympathetic observation, will be found of great value to those who are anxious to arrive at a correct appreciation of Christian enterprise in these remote regions. Descriptions of missionaries and their doings are too often marred by exaggerations of success on the one hand, which are, perhaps, the natural outcome of enthusiasm, and harsh and frequently unjust criticisms on the other, commonly indulged in by those who base their conclusions upon observation of the most superficial kind. Speaking from my own experience, I have no hesitation in saying that closer inquiry would dispel many of the illusions about the futility of missionary work that are, unfortunately, too common; and that missionaries would, as a rule, welcome sympathetic inquiry into their methods of work, which most of them will frankly admit to be capable of improvement. But, while courting friendly criticism, they may reasonably object to be judged by those who have never taken the trouble to study their system, or to interest themselves in the objects they have in view. In Mrs. Bishop they have an advocate whose testimony may be commended to the attention of all who are disposed to regard missionary labor as, at the best, useless or unnecessary. In Korea, at all events, to go no farther, it is to missionaries that we are assuredly indebted for almost all we know about the country; it is they who have awakened in the people the desire for material progress and enlightenment that has now happily taken root, and it is to them that we may confidently look for assistance in its farther development. The unacknowledged, but none the less complete, religious toleration that now exists throughout the country affords them facilities which are being energetically used with great promise of future success. I am tempted to call attention to another point in connection with this much-abused class of workers that is, I think, often lost sight of, namely, their utility as explorers and pioneers of commerce. They are always ready—at least such has been my invariable experience—to place the stores of their local knowledge at the disposal of any one, whether merchant, sportsman, or traveler, who applies to them for information, and to lend him cheerful assistance in the pursuit of his objects. I venture to think that much valuable information as to channels for the development of trade could be obtained by Chambers of Commerce if they were to address specific inquiries to missionaries in remote regions. Manufacturers are more indebted to missionaries than perhaps they realize for the introduction of their goods and wares, and the creation of a demand for them, in places to which such would never otherwise have found their way.

It is fortunate that Mrs. Bishop’s visit to Korea was so opportunely timed. At the present rate of progress much that came under her observation will, before long, be “improved” out of existence; and though no one can regret the disappearance of many institutions and customs that have nothing but their antiquity to recommend them, she has done valuable service in placing on record so graphic a description of experiences that future travelers will probably look for in vain.

WALTER C. HILLIER.

October, 1897.

Author’s Prefatory Note.

My four visits to Korea, between January, 1894, and March, 1897, formed part of a plan of study of the leading characteristics of the Mongolian races. My first journey produced the impression that Korea is the most uninteresting country I ever traveled in, but during and since the war its political perturbations, rapid changes, and possible destinies, have given me an intense interest in it; while Korean character and industry, as I saw both under Russian rule in Siberia, have enlightened me as to the better possibilities which may await the nation in the future. Korea takes a similarly strong grip on all who reside in it sufficiently long to overcome the feeling of distaste which at first it undoubtedly inspires.

It is a difficult country to write upon, from the lack of books of reference by means of which one may investigate what one hopes are facts, the two best books on the country having become obsolete within the last few years in so far as its political condition and social order are concerned. The traveler must laboriously disinter each fact for himself, usually through the medium of an interpreter; and as five or six versions of each are given by apparently equally reliable authorities, frequently the “teachers” of the foreigners, the only course is to hazard a bold guess as to which of them has the best chance of being accurate.

Accuracy has been my first aim, and my many foreign friends in Korea know how industriously I have labored to attain it. It is by these, who know the extreme difficulty of the task, that I shall be the most leniently criticised wherever, in spite of carefulness, I have fallen into mistakes.

Circumstances prevented me from putting my traveling experiences, as on former occasions, into letters. I took careful notes, which were corrected from time to time by the more prolonged observations of residents, and as I became better acquainted with the country; but, with regard to my journey up the South Branch of the Han, as I am the first traveler who has reported on the region, I have to rely on my observation and inquiries alone, and there is the same lack of recorded notes on most of the country on the Upper Tai-döng. My notes furnish the travel chapters, as well as those on Seoul, Manchuria, and Primorsk; and the sketches in contemporary Korean history are based partly on official documents, and are partly derived from sources not usually accessible.

I owe very much to the kindly interest which my friends in Korea took in my work, and to the encouragement which they gave me when I was disheartened by the difficulties of the subject and my own lack of skill. I gratefully acknowledge the invaluable help given me by Sir Walter C. Hillier, K.C.M.G., H.B.M.’s Consul-General in Korea, and Mr. J. M’Leavy Brown, LL.D., Chief Commissioner of Korean Customs; also the aid generously bestowed by Mr. Waeber, the Russian Minister, and the Rev. G. Heber Jones, the Rev. James Gale, and other missionaries. I am also greatly indebted to a learned and careful volume on Korean Government, by Mr. W. H. Wilkinson, H.B.M.’s Acting Vice-Consul at Chemulpo, as well as to the Korean Repository and the Seoul Independent, for information which has enabled me to correct some of my notes on Korean customs.

Various repetitions occur, for the reason that it appears to me impossible to give sufficient emphasis to certain facts without them; and several descriptions are loaded with details, the result of an attempt to fix on paper customs and ceremonies destined shortly to disappear. The illustrations, with the exceptions of three, are reproductions of my own photographs. The sketch map, in so far as my first journey is concerned, is reduced from one kindly drawn for me by Mr. Waeber. The transliteration of Chinese proper names was kindly undertaken by a well-known Chinese scholar, but unfortunately the actual Chinese characters were not in all cases forthcoming. In justice to the kind friends who have so generously aided me, I am anxious to claim and accept the fullest measure of personal responsibility for the opinions expressed, which, whether right or wrong, are wholly my own.

I am painfully conscious of the demerits of this work, but believing that, on the whole, it reflects fairly faithfully the regions of which it treats, I venture to present it to the public; and to ask for it the same kindly and lenient criticism with which my records of travel in the East and elsewhere have hitherto been received, and that it may be accepted as an honest attempt to make a contribution to the sum of the knowledge of Korea and its people, and to describe things as I saw them, not only in the interior but in the troubled political atmosphere of the capital.

ISABELLA L. BISHOP.

November, 1897.

Contents

| Chapter | Page | |

| Introductory Chapter | 11 | |

| I. | First Impressions of Korea | 23 |

| II. | First Impressions of the Capital | 35 |

| III. | The Kur-dong | 49 |

| IV. | Seoul, the Korean Mecca | 59 |

| V. | The Sailing of the Sampan | 66 |

| VI. | On the River of Golden Sand | 71 |

| VII. | Views Afloat | 82 |

| VIII. | Natural Beauty—The Rapids | 98 |

| IX. | Korean Marriage Customs | 114 |

| X. | The Korean Pony—Korean Roads and Inns | 121 |

| XI. | Diamond Mountain Monasteries | 133 |

| XII. | Along the Coast | 150 |

| XIII. | Impending War—Excitement at Chemulpo | 177 |

| XIV. | Deported to Manchuria | 185 |

| XV. | A Manchurian Deluge—A Passenger Cart—An Accident | 192 |

| XVI. | Mukden and its Missions | 199 |

| XVII. | Chinese Troops on the March | 206 |

| XVIII. | Nagasaki—Wladivostok | 213 |

| XIX. | Korean Settlers in Siberia | 223 |

| XX. | The Trans-Siberian Railroad | 239 |

| XXI. | The King’s Oath—An Audience | 245 |

| XXII. | A Transition Stage | 261 |

| XXIII. | The Assassination of the Queen | 269 |

| XXIV. | Burial Customs | 283 |

| XXV. | Song-do: A Royal City | 292 |

| XXVI. | The Phyong-yang Battlefield | 301 |

| XXVII. | Northward Ho! | 320 |

| XXVIII. | Over the An-kil Yung Pass | 330 |

| XXIX. | Social Position of Women | 338 |

| XXX. | Exorcists and Dancing Women | 344 |

| XXXI. | The Hair-cropping Edict | 359 |

| XXXII. | The Reorganized Korean Government | 371 |

| XXXIII. | Education and Foreign Trade | 387 |

| XXXIV. | Dæmonism or Shamanism | 399 |

| XXXV. | Notes on Dæmonism Concluded | 409 |

| XXXVI. | Seoul in 1897 | 427 |

| XXXVII. | Last Words on Korea | 445 |

| Appendixes | 461 | |

| Appendix A.—Mission Statistics for Korea 1896. | ||

| Appendix B.—Direct Foreign Trade of Korea 1886-95. | ||

| Appendix C.—Return of Principal Articles of Export for the years 1896-95. | ||

| Appendix D.—Population of Treaty Ports. | ||

| Appendix E.—Treaty between Japan and Russia, with reply of H.E., the Korean Minister for Foreign Affairs. | ||

| Index | 475 |

List of Illustrations.

| Page | |

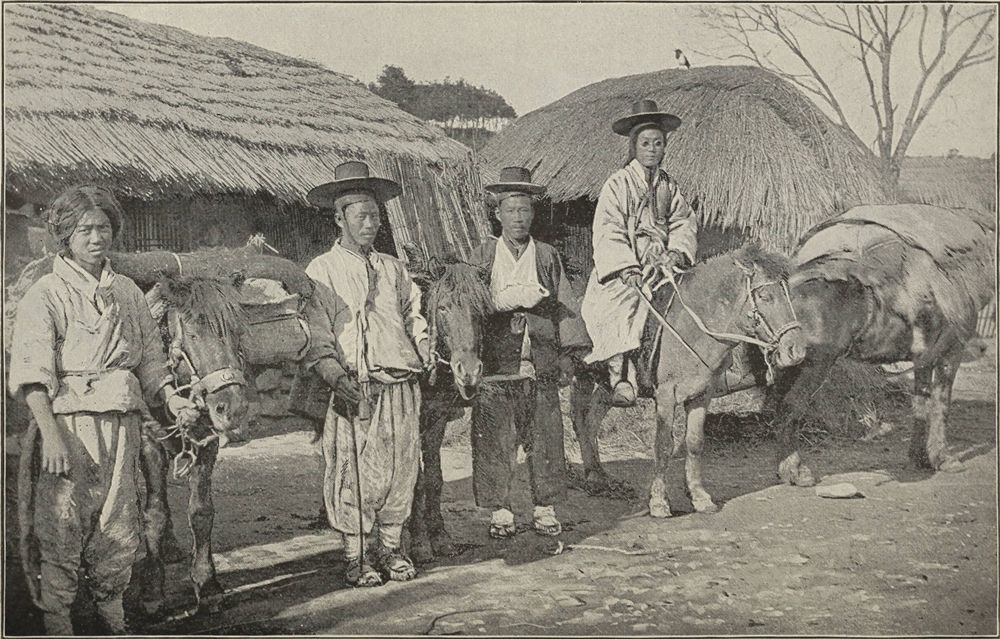

| Mrs. Bishop’s Traveling Party | Frontispiece |

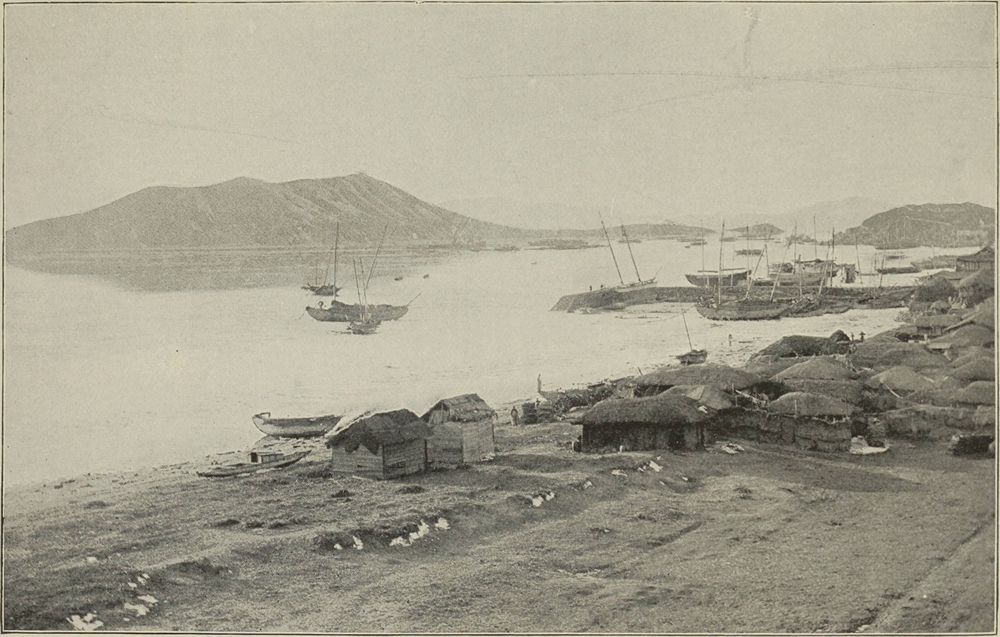

| Harbor of Chemulpo | Facing 30 |

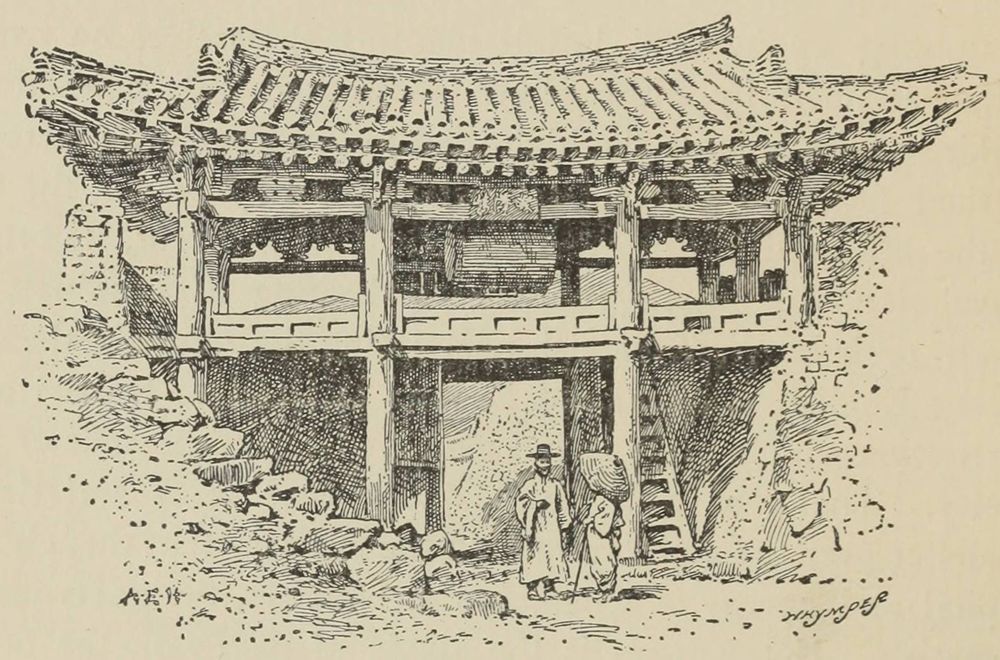

| Gate of Old Fusan | 34 |

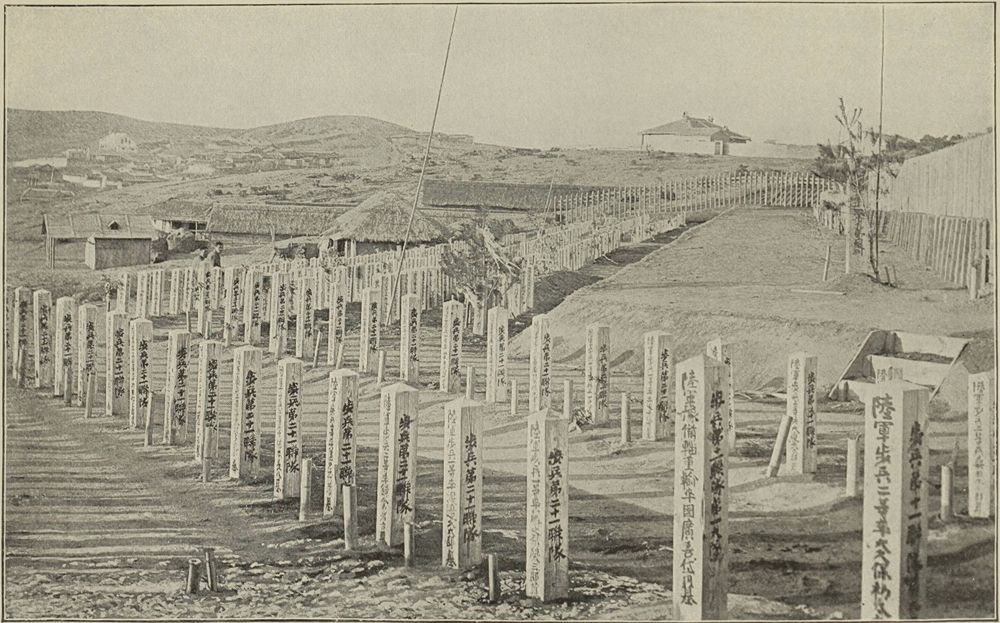

| Japanese Military Cemetery, Chemulpo | Facing 38 |

| Turtle Stone | 48 |

| Gutter Shop, Seoul | Facing 60 |

| The Author’s Sampan, Han River | Facing 66 |

| Korean Peasants at Dinner | 81 |

| A Korean Lady | 120 |

| The Diamond Mountains | Facing 140 |

| Tombstones of Abbots, Yu-Chöm Sa | Facing 146 |

| Passenger Cart, Mukden | 198 |

| Temple of God of Literature, Mukden | Facing 200 |

| Gate of Victory, Mukden | Facing 208 |

| Chinese Soldiers | Facing 210 |

| Wladivostok | Facing 214 |

| Russian “Army,” Krasnoye Celo | Facing 232 |

| Korean Settler’s House | 238 |

| Korean Throne | Facing 248 |

| Summer Pavilion, or “Hall of Congratulations” | Facing 254 |

| Royal Library, Kyeng-Pok Palace | Facing 256 |

| Korean Gentleman in Court Dress | 260 |

| Place of the Queen’s Cremation | 268 |

| Chil-Sung Mon, Seven Star Gate | 300 |

| Altar at Tomb of Kit-ze | Facing 318 |

| Russian Settler’s House | Facing 320 |

| Upper Tai-Döng | Facing 324 |

| Russian Officers, Hun-Chun | Facing 330 |

| South Gate | Facing 412 |

| Seoul and Palace Enclosure | Facing 428 |

| The King of Korea | Facing 430 |

| Korean Cadet Corps and Russian Drill Instructors | 434 |

| A Street in Seoul | Facing 436 |

| Korean Policemen, Old and New | 444 |

The Edinburgh Geographical Institute John Bartholomew & Co.

Fleming H. Revell Company.

Korea and Her Neighbors

INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER

In the winter of 1894, when I was about to sail for Korea (to which some people erroneously give the name of “The Korea”), many interested friends hazarded guesses at its position,—the Equator, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea being among them, a hazy notion that it is in the Greek Archipelago cropping up frequently. It was curious that not one of these educated, and, in some cases, intelligent people came within 2,000 miles of its actual latitude and longitude!

In truth, there is something about this peninsula which has repelled investigation, and until lately, when the establishment of a monthly periodical, carefully edited, The Korean Repository, has stimulated research, the one authority of which all writers, with and without acknowledgment, have availed themselves, is the Introduction to Père Dallet’s Histoire de l’Église de Korée, a valuable treatise, many parts of which, however, are now obsolete.

If in this volume I present facts so elementary as to provoke the scornful comment, “Every schoolboy knows that,” I venture to remind my critics that the larger number of possible readers were educated when Korea was little more than “a geographical expression,” and had not the advantages of the modern schoolboy, whose “up-to-date” geographical text-books have been written since the treaties of 1883 opened the Hermit Nation to the world; and I will ask the minority to be patient with what may be to them “twice-told tales” for the sake of the majority, specially in this introduction, which is intended to give something of lucidity to the chapters which follow.

The first notice of Korea is by Khordadbeh, an Arab geographer of the ninth century, A.D., in his Book of Roads and Provinces, quoted by Baron Richofen in his work on China, p. 575. Legends of the aboriginal inhabitants of the peninsula are too mythical to be noticed here, but it is certain that it was inhabited when Kit-ze or Ki-ja, who will be referred to later, introduced the elements of Chinese civilization in the twelfth century B.C. Naturally that conquest and subsequent immigrations from Manchuria have left some traces on the Koreans, but they are strikingly dissimilar from both their nearest neighbors, the Chinese and the Japanese, and there is a remarkable variety of physiognomy among them, all the more noticeable because of the uniformity of costume. The difficulty of identifying people which besets and worries the stranger in Japan and China does not exist in Korea. It is true that the obliquity of the Mongolian eye is always present, as well as a trace of bronze in the skin, but the complexion varies from a swarthy olive to a very light brunette.

There are straight and aquiline noses, as well as broad and snub noses with distended nostrils; and though the hair is dark, much of it is so distinctly a russet brown as to require the frequent application of lampblack and oil to bring it to a fashionable black, while in texture it varies from wiriness to silkiness. Some men have full moustaches and large goatees, on the faces of others a few carefully tended hairs, as in China, do duty for both, while many have full, strong beards. The mouth is either the wide, full-lipped, gaping cavity constantly seen among the lower orders, or a small though full feature, or thin-lipped and refined, as is seen continually among patricians.

The eyes, though dark, vary from dark brown to hazel; the cheek bones are high; the brow, so far as fashion allows it to be seen, is frequently lofty and intellectual; and the ears are small and well set on. The usual expression is cheerful, with a dash of puzzlement. The physiognomy indicates, in its best aspect, quick intelligence, rather than force or strength of will. The Koreans are certainly a handsome race.

The physique is good. The average height of the men is five feet four and a half[1] inches, that of the women cannot be ascertained, and is disproportionately less, while their figureless figures, the faults of which are exaggerated by the ugliest dress on earth, are squat and broad. The hands and feet of both sexes and all classes are very small, white, and exquisitely formed, and the tapering, almond-shaped finger-nails are carefully attended to. The men are very strong, and as porters carry heavy weights, a load of 100 pounds being regarded as a moderate one. They walk remarkably well, whether it be the studied swing of the patrician or the short, firm stride of the plebeian when on business. The families are large and healthy. If the Government estimate of the number of houses is correct, the population, taking a fair average, is from twelve to thirteen millions, females being in the minority.

Mentally the Koreans are liberally endowed, specially with that gift known in Scotland as “gleg at the uptak.” The foreign teachers bear willing testimony to their mental adroitness and quickness of perception, and their talent for the rapid acquisition of languages, which they speak more fluently and with a far better accent than either the Chinese or Japanese. They have the Oriental vices of suspicion, cunning, and untruthfulness, and trust between man and man is unknown. Women are secluded, and occupy a very inferior position.

The geography of Korea, or Ch’ao Hsien (“Morning Calm,” or “Fresh Morning”), is simple. It is a definite peninsula to the northeast of China, measuring roughly 600 miles from north to south and 135 from east to west. The coast line is about 1,740 miles. It lies between 34° 17′ N. to 43° N. latitude and 124° 38′ E. to 130° 33′ E. longitude, and has an estimated area of upwards of 80,000 square miles, being somewhat smaller than Great Britain. Bounded on the north and west by the Tu-men and Am-nok, or Yalu, rivers, which divide it from the Russian and Chinese empires, and by the Yellow Sea, its eastern and southern limit is the Sea of Japan, a “silver streak,” which has not been its salvation. Its northern frontier is only conterminous with that of Russia for 11 miles.

Both boundary rivers rise in Paik-tu San, the “White-Headed Mountain,” from which runs southwards a great mountain range, throwing off numerous lateral spurs, itself a rugged spine which divides the kingdom into two parts, the eastern division being a comparatively narrow strip between the range and the Sea of Japan, difficult of access, but extremely fertile; while the western section is composed of rugged hills and innumerable rich valleys and slopes, well watered and admirably suited for agriculture. Craters of volcanoes, long since passed into repose, lava beds, and other signs of volcanic action, are constantly met with.

The lakes are few and very small, and not many of the streams are navigable for more than a few miles from the sea, the exceptions being the noble Am-nok, the Tai-döng, the Nak-tong, the Mok-po, and the Han, which last, rising in Kang-wön Do, 30 miles from the Sea of Japan, after cutting the country nearly in half, falls into the sea at Chemulpo on the west coast, and, in spite of many and dangerous rapids, is a valuable highway for commerce for over 170 miles.

Owing to the configuration of the peninsula there are few good harbors, but those which exist are open all the winter. The finest are Fusan and Wön-san, on Broughton Bay. Chemulpo, which, as the port of Seoul, takes the first place, can hardly be called a harbor at all, the “outer harbor,” where large vessels and ships of war lie, being nothing better than a roadstead, and the “inner harbor,” close to the town, in the fierce tideway of the estuary of the Han, is only available for five or six vessels of small tonnage at a time. The east coast is steep and rocky, the water is deep, and the tide rises and falls from 1 to 2 feet only. On the southwest and west coasts the tide rises and falls from 26 to 38 feet!

Off the latter coasts there is a remarkable archipelago. Some of the islands are bold masses of arid rock, the resort of seafowl; others are arable and inhabited, while the actual coast fringes off into innumerable islets, some of which are immersed by the spring tides. In the channels scoured among these by the tremendous rush of the tide, navigation is ofttimes dangerous. Great mud-banks, specially near the mouths of the rivers, render parts of the coast-line dubious.

Korea is decidedly a mountainous country, and has few plains deserving the name. In the north there are mountain groups with definite centres, the most remarkable being Paik-tu San, which attains an altitude of over 8,000 feet, and is regarded as sacred. Farther south these settle into a definite range, following the coast-line at a moderate distance, and throwing out so many ranges and spurs to the west as to break up northern and central Korea into a congeries of corrugated and precipitous hills, either denuded or covered with chapparal, and narrow, steep-sided valleys, each furnished with a stony stream. The great axial range, which includes the “Diamond Mountain,” a region containing exquisite mountain and sylvan scenery, falls away as it descends towards the southern coast, disintegrating in places into small and often infertile plains.

The geological formation is fairly simple. Mesozoic rocks occur in Hwang-hai Do, but granite and metamorphic rocks largely predominate. Northeast of Seoul are great fields of lava, and lava and volcanic rocks are of common occurrence in the north.

The climate is undoubtedly one of the finest and healthiest in the world. Foreigners are not afflicted by any climatic maladies, and European children can be safely brought up in every part of the peninsula. July, August, and sometimes the first half of September, are hot and rainy, but the heat is so tempered by sea breezes that exercise is always possible. For nine months of the year the skies are generally bright, and a Korean winter is absolutely superb, with its still atmosphere, its bright, blue, unclouded sky, its extreme dryness without asperity, and its crisp, frosty nights. From the middle of September till the end of June, there are neither extremes of heat nor cold to guard against.

The summer mean temperature at Seoul is about 75° Fahrenheit, that of the winter about 33°; the average rainfall 36.03 inches in the year, and the average of the rainy season 21.86 inches.[2] July is the wettest month, and December the driest. The result of the abundant rainfall, distributed fairly through the necessitous months of the year, is that irrigation is necessary only for the rice crop.

The fauna of Korea is considerable, and includes tigers and leopards in great numbers, bears, antelopes, at least seven species of deer, foxes, beavers, otters, badgers, tiger-cats, pigs, several species of marten, a sable (not of much value, however), and striped squirrels. Among birds there are black eagles, found even near Seoul, harriers, peregrines (largely used for hawking), pheasants, swans, geese, spectacled and common teal, mallards, mandarin ducks, turkey buzzards (very shy), white and pink ibis, sparrow-hawks, kestrels, imperial cranes, egrets, herons, curlews, night-jars, redshanks, buntings, magpies (common and blue), orioles, wood larks, thrushes, redstarts, crows, pigeons, doves, rooks, warblers, wagtails, cuckoos, halcyon and bright blue kingfishers, jays, snipes, nut-hatches, gray shrikes, pheasants, hawks, and kites. But until more careful observations have been made it is impossible to say which of the smaller birds actually breed in Korea, and which make it only a halting-place in their annual migrations.

The denudation of the hills in the neighborhood of Seoul, the coasts, the treaty ports, and the main roads, is impressive, and helps to give a very unfavorable idea of the country. It is to the dead alone that the preservation of anything deserving the name of timber in much of southern Korea is owing. But in the mountains of the northern and eastern provinces, and specially among those which enclose the sources of the Tu-men, the Am-nok, the Tai-döng, and the Han, there are very considerable forests, on which up to this time the woodcutter has made little apparent impression, though a good deal of timber is annually rafted down these rivers.

Among the indigenous trees are the Abies excelsa, Abies microsperma, Pinus sinensis, Pinus pinea, three species of oak, the lime, ash, birch, five species of maple, the Acanthopanax ricinifolia, Rhus semipinnata, Elæagnus, juniper, mountain ash, hazel, Thuja Orientalis (?), willow, Sophora Japonica (?), hornbeam, plum, peach, Euonymus alatus, etc. The flora is extensive and interesting, but, with the exception of the azalea and rhododendron, it lacks brilliancy of color. There are several varieties of showy clematis, and the mille-fleur rose smothers even large trees, but the climber par excellence of Korea is the Ampelopsis Veitchii. The economic plants are few, and, with the exception of the Panax quinquefolia (ginseng), the wild roots of which are worth $15 per ounce, are of no commercial value.

The mineral wealth of Korea is a vexed question. Probably between the view of the country as an El Dorado and the scepticism as to the existence of underground treasure at all, the mean lies. Gold is little used for personal ornaments or in the arts, yet the Korean declares that the dust of his country is gold; and the unquestionable authority of a Customs’ report states that gold dust to the amount of $1,360,279 was exported in 1896, and that it is probable that the quantity which left the country undeclared was at least as much again. Silver and galena are found, copper is fairly plentiful, and the country is rich in undeveloped iron and coal mines, the coal being of excellent quality. The gold-bearing quartz has never been touched, but an American Company, having obtained a concession, has introduced machinery, and has gone to work in the province of Phyöng-an.

The manufactures are unimportant. The best productions are paper of several qualities made from the Brousonettia Papyrifera, among which is an oiled paper, like vellum in appearance, and so tough that a man can be raised from the ground on a sheet of it, lifted at the four corners, fine grass mats, and split bamboo blinds.

The arts are nil.

Korea, or Ch’ao Hsien, has been ruled by kings of the present dynasty since 1392. The monarchy is hereditary, and though some modifications in a constitutional direction were made during the recent period of Japanese ascendency, the sovereign is still practically absolute, his edicts, as in China, constituting law. The suzerainty of China, recognized since very remote days, was personally renounced by the king at the altar of the Spirits of the Land in January, 1895, and the complete independence of Korea was acknowledged by China in the treaty of peace signed at Shimonoseki in May of the same year. There is a Council of State composed of a chancellor, five councillors, six ministers, and a chief secretary. The decree of September, 1896, which constitutes this body, announces the king’s absolutism in plain terms in the preamble.

There are nine ministers—the Prime Minister, Minister of the Royal Household, of Finance, of Home Affairs, Foreign Affairs, War, Justice, Agriculture, and Education, but the royal will (or whim) overrides their individual or collective decisions.

The Korean army consists of 4,800 men in Seoul, drilled by Russians, and 1,200 in the provinces; the navy, of two small merchant steamers.

Korea is divided into 13 provinces and 360 magisterial districts.

The revenue, which is amply sufficient for all legitimate expenses, is derived from Customs’ duties, under the able and honest management of officers lent by the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs: a land tax of $6 on every fertile kyel (a fertile kyel being estimated at about 6¹⁄₃ acres), and $5 on every mountain kyel; a household tax of 60 cents per house, houses in the capital enjoying immunity; and a heavy excise duty of $16 per cattie on manufactured ginseng.

Up to 1876 Korea successfully preserved her isolation, and repelled with violence any attempt to encroach upon it. In that year Japan forced a treaty upon her, and in 1882 China followed with “Trade and Frontier Regulations.” The United States negotiated a treaty in 1882, Great Britain and Germany in 1884, Russia and Italy in 1886, and Austria in 1892, in all which, though under Chinese suzerainty, Korea was treated with as an independent state. By these treaties, Seoul and the ports of Chemulpo (Jenchuan), Fusan, and Wön-san (Gen-san) were opened to foreign commerce, and this year (1897) Mok-po and Chinnam-po have been added to the list.

After the treaties were signed, a swarm of foreign representatives settled down upon the capital, where three of them are housed in handsome and conspicuous foreign buildings. The British Minister at Peking is accredited also to the Korean Court, and Britain has a resident Consul-General. Japan, Russia, and America are represented by Ministers, France by a Chargé d’Affaires, and Germany by a Consul. China, which has been tardy in entering upon diplomatic relations with Korea since the war, placed her subjects under the protection of the British Consul-General.

Until recently, the coinage of Korea consisted of debased copper cash, 500 to the dollar, a great check on business transactions; but a new fractional coinage, of which the unit is a 20-cent piece, has been put into circulation, along with 5-cent nickel, 5-cash copper, and 1-cash brass pieces. The fine Japanese yen or dollar is now current everywhere. The Dai Ichi Gingo and Fifty-eighth Banks of Japan afford banking facilities in Seoul and the open ports.

In the treaty ports of Fusan, Wön-san, and Chemulpo, there were in January, 1897, 11,318 foreign residents and 266 foreign business firms. The Japanese residents numbered 10,711, and their firms 230. The great majority of the American and French residents are missionaries, and the most conspicuous objects in Seoul are the Roman Cathedral and the American Methodist Episcopal Church. The number of British subjects in Korea in January, 1897, was 65, and an agency of a British firm in Nagasaki has recently been opened at Chemulpo. The approximate number of Chinese in Korea at the same time was 2,500, divided chiefly between Seoul and Chemulpo. There is a newly-instituted postal system for the interior, with postage stamps of four denominations, and a telegraph system, Seoul being now in communication with all parts of the world.

The roads are infamous, and even the main roads are rarely more than rough bridle tracks. Goods are carried everywhere on the backs of men, bulls, and ponies, but a railroad from Chemulpo to Seoul, constructed by an American concessionaire, is actually to be opened shortly.

The language of Korea is mixed. The educated classes introduce Chinese as much as possible into their conversation, and all the literature of any account is in that language, but it is of an archaic form, the Chinese of 1,000 years ago, and differs completely in pronunciation from Chinese as now spoken in China. En-mun, the Korean script, is utterly despised by the educated, whose sole education is in the Chinese classics. Korean has the distinction of being the only language of Eastern Asia which possesses an alphabet. Only women, children, and the uneducated used the En-mun till January, 1895, when a new departure was made by the official Gazette, which for several hundred years had been written in Chinese, appearing in a mixture of Chinese characters and En-mun, a resemblance to the Japanese mode of writing, in which the Chinese characters which play the chief part are connected by kana syllables.

A further innovation was that the King’s oath of Independence and Reform was promulgated in Chinese, pure En-mun, and the mixed script, and now the latter is regularly employed as the language of ordinances, official documents, and the Gazette; royal rescripts, as a rule, and despatches to the foreign representatives still adhering to the old form.

This recognition of the Korean language by means of the official use of the mixed, and in some cases of the pure script, the abolition of the Chinese literary examinations as the test of the fitness of candidates for office, the use of the “vulgar” script exclusively in the Independent, the new Korean newspaper, the prominence given to Korean by the large body of foreign missionaries, and the slow creation of scientific text-books and a literature in En-mun, are tending not only to strengthen Korean national feeling, but to bring the “masses,” who can mostly read their own script, into contact with Western science and forms of thought.

There is no national religion. Confucianism is the official cult, and the teachings of Confucius are the rule of Korean morality. Buddhism, once powerful, but “disestablished” three centuries ago, is to be met with chiefly in mountainous districts, and far from the main roads. Spirit worship, a species of shamanism, prevails all over the kingdom, and holds the uneducated masses and the women of all classes in complete bondage.

Christian missions, chiefly carried on by Americans, are beginning to produce both direct and indirect effects.

Ten years before the opening[3] of Korea to foreigners, the Korean king, in writing to his suzerain, the Emperor of China, said, “The educated men observe and practice the teachings of Confucius and Wen Wang,” and this fact is the key to anything like a correct estimate of Korea. Chinese influence in government, law, education, etiquette, social relations, and morals is predominant. In all these respects Korea is but a feeble reflection of her powerful neighbor; and though since the war the Koreans have ceased to look to China for assistance, their sympathies are with her, and they turn to her for noble ideals, cherished traditions, and moral teachings. Their literature, superstitions, system of education, ancestral worship, culture, and modes of thinking are Chinese. Society is organized on Confucian models, and the rights of parents over children, and of elder over younger brothers, are as fully recognized as in China.

It is into this archaic condition of things, this unspeakable grooviness, this irredeemable, unreformed Orientalism, this parody of China without the robustness of race which helps to hold China together, that the ferment of the Western leaven has fallen, and this feeblest of independent kingdoms, rudely shaken out of her sleep of centuries, half frightened and wholly dazed, finds herself confronted with an array of powerful, ambitious, aggressive, and not always overscrupulous powers, bent, it may be, on overreaching her and each other, forcing her into new paths, ringing with rude hands the knell of time-honored custom, clamoring for concessions, and bewildering her with reforms, suggestions, and panaceas, of which she sees neither the meaning nor the necessity.

And so “The old order changeth, giving place to new,” and many indications of the transition will be found in the later of the following pages.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] The following are the measurements of 1,060 men taken at Seoul in January, 1897, by Mr. A. B. Stripling:—

| Highest. | Lowest. | Average. | |

| Height | 5 ft. 11¹⁄₄ in. | 4 ft. 9¹⁄₂ in. | 5 ft. 4¹⁄₂ in. |

| Size round chest | 39¹⁄₄ in. | 27 in. | 31 in. |

| “ head | 23¹⁄₄ “ | 20 “ | 21¹⁄₂ “ |

[2] These averages are only calculated on observations taken during a period of three and a half years.

[3] See appendix A.

CHAPTER I

FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF KOREA

It is but fifteen hours’ steaming from the harbor of Nagasaki to Fusan in Southern Korea. The Island of Tsushima, where the Higo Maru calls, was, however, my last glimpse of Japan; and its reddening maples and blossoming plums, its temple-crowned heights, its stately flights of stone stairs leading to Shinto shrines in the woods, the blue-green masses of its pines, and the golden plumage of its bamboos, emphasized the effect produced by the brown, bare hills of Fusan, pleasant enough in summer, but grim and forbidding on a sunless February day. The Island of the Interrupted Shadow, Chŏl-yong-To, (Deer Island), high and grassy, on which the Japanese have established a coaling station and a quarantine hospital, shelters Fusan harbor.

It is not Korea but Japan which meets one on anchoring. The lighters are Japanese. An official of the Nippon Yusen Kaisha (Japan Mail Steamship Co.), to which the Higo Maru belongs, comes off with orders. The tide-waiter, however, is English—one of the English employés of the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs, lent to Korea, greatly to her advantage, for the management of her customs’ revenue. The foreign settlement of Fusan is dominated by a steep bluff with a Buddhist temple on the top, concealed by a number of fine cryptomeria, planted during the Japanese occupation in 1592. It is a fairly good-looking Japanese town, somewhat packed between the hills and the sea, with wide streets of Japanese shops and various Anglo-Japanese buildings, among which the Consulate and a Bank are the most important. It has substantial retaining and sea walls, and draining, lighting, and roadmaking have been carried out at the expense of the municipality. Since the war, waterworks have been constructed by a rate of 100 cash levied on each house, and it is hoped that the present abundant supply of pure water will make an end of the frequent epidemics of cholera. Above the town, the new Japanese military cemetery, filling rapidly, is the prominent object.

Considering that the creation of a demand for foreign goods is not thirteen years old, it is amazing to find how the Koreans have taken to them, and that the foreign trade of Fusan has developed so rapidly that, while in 1885 the value of exports and imports combined only amounted to £77,850, in 1892 it had reached £346,608. Unbleached shirtings, lawns, muslins, cambrics, and Turkey reds for children’s wear have all captivated Korean fancy; but the conservatism of wadded cotton garments in winter does not yield to foreign woollens, of which the importation is literally nil. The most amazing stride is in the importation of American kerosene oil, which has reached 71,000 gallons in a quarter; and which, by displacing the fish-oil lamp and the dismal rushlight in the paper lantern, is revolutionizing evening life in Korea. Matches, too, have “caught on” wonderfully, and evidently have “come to stay.” Hides, beans, dried fish, bêche de mer, rice, and whale’s flesh are among the principal exports. It was not till 1883 that Fusan was officially opened to general foreign trade, and its rise has been most remarkable. In that year its foreign population was 1,500; in 1897 it was 5,564.

In the first half of 1885 the Japan Mail Steamship Co. ran only one steamer, calling at Fusan, to Wladivostok every five weeks, and a small boat to Chemulpo, calling at Fusan, once a month. Now not a day passes without steamers, large or small, arriving at the port, and in addition to the fine vessels of the Nippon Yusen Kaisha, running frequently between Kobe and Wladivostok, Shanghai and Wladivostok, Kobe and Tientsin, and between Kobe Chefoo, and Newchang, all calling at Fusan, three other lines, including one from Osaka direct, and a Russian mail line running between Shanghai and Wladivostok, make Fusan a port of call.

It appears that about one-third of the goods imported is carried inland on the backs of men and horses. The taxes levied and the delays at the barriers on both the overland and river routes are intolerable to traders, a hateful custom prevailing under which each station is controlled by some petty official, who, for a certain sum paid to the Government in Seoul, obtains permission to levy taxes on all goods.[4] The Nak-Tong River, the mouth of which is 7 miles from Fusan, is navigable for steamers drawing 5 feet of water as far as Miriang, 50 miles up, and for junks drawing 4 feet as far as Sa-mun, 100 miles farther, from which point their cargoes, transhipped into light draught boats, can ascend to Sang-chin, 170 miles from the coast. With this available waterway, and a hazy prospect that the much disputed Seoul-Fusan railway may become an accomplished fact, Fusan bids fair to become an important centre of commerce, as the Kyöng-sang Province, said to be the most populous of the eight (now for administrative purposes thirteen), is also said to be the most prosperous and fruitful, with the possible exception of Chul-la.

Barren as the neighboring hills look, they are probably rich in minerals. Gold is found in several places within a radius of 50 miles, copper quite near, and there are coal fields within 100 miles.

To all intents and purposes the settlement of Fusan is Japanese. In addition to the Japanese population of 5,508, there is a floating population of 8,000 Japanese fishermen. A Japanese Consul-General lives in a fine European house. Banking facilities are furnished by the Dai Ichi Gingo of Tokio, and the post and telegraph services are also Japanese. Japanese too is the cleanliness of the settlement, and the introduction of industries unknown to Korea, such as rice husking and cleaning by machinery, whale-fishing, sake-making, and the preparation of shark’s fins, bêche de mer, and fish manure, the latter an unsavory fertilizer, of which enormous quantities are exported to Japan.

But the reader asks impatiently, “Where are the Koreans? I don’t want to read about the Japanese!” Nor do I want to write about them, but facts are stubborn, and they are the outstanding Fusan fact.

As seen from the deck of the steamer, a narrow up and down path keeping at some height above the sea skirts the hillside for 3 miles from Fusan, passing by a small Chinese settlement with official buildings, uninhabited when I last saw them, and terminating in the walled town of Fusan proper, with a fort of very great antiquity outside it, modernized by the Japanese after the engineering notions of three centuries ago.

Seated on the rocks along the shore were white objects resembling pelicans or penguins, but as white objects with the gait of men moved in endless procession to and fro between old and new Fusan, I assumed that the seated objects were of the same species. The Korean makes upon one the impression of novelty, and while resembling neither the Chinese nor the Japanese, he is much better-looking than either, and his physique is far finer than that of the latter. Though his average height is only 5 feet 4¹⁄₂ inches, his white dress, which is voluminous, makes him look taller, and his high-crowned hat, without which he is never seen, taller still. The men were in winter dress—white cotton sleeved robes, huge trousers, and socks; all wadded. On their heads were black silk wadded caps with pendant sides edged with black fur, and on the top of these, rather high-crowned, somewhat broad-brimmed hats of black “crinoline” or horsehair gauze, tied under the chin with crinoline ribbon. The general effect was grotesque. There were a few children on the path, bundles of gay clothing, but no women.

I was accompanied to old Fusan by a charming English “Una,” who, speaking Korean almost like a native, moved serenely through the market-day crowds, welcomed by all. A miserable place I thought it, and later experience showed that it was neither more nor less miserable than the general run of Korean towns. Its narrow dirty streets consist of low hovels built of mud-smeared wattle without windows, straw roofs, and deep eaves, a black smoke-hole in every wall 2 feet from the ground, and outside most are irregular ditches containing solid and liquid refuse. Mangy dogs and blear-eyed children, half or wholly naked, and scaly with dirt, roll in the deep dust or slime, or pant and blink in the sun, apparently unaffected by the stenches which abound. But market-day hid much that is repulsive. Along the whole length of the narrow, dusty, crooked street, the wares were laid out on mats on the ground, a man or an old woman, bundled up in dirty white cotton, guarding each. And the sound of bargaining rose high, and much breath was spent on beating down prices, which did not amount originally to the tenth part of a farthing. The goods gave an impression of poor buyers and small trade. Short lengths of coarse white cotton, skeins of cotton, straw shoes, wooden combs, tobacco pipes and pouches, dried fish and seaweed, cord for girdles, paper rough and smooth, and barley-sugar nearly black, were the contents of the mats. I am sure that the most valuable stock-in-trade there was not worth more than three dollars. Each vendor had a small heap of cash beside him, an uncouth bronze coin with a square hole in the centre, of which at that time 3,200 nominally went to the dollar, and which greatly trammelled and crippled Korean trade.

A market is held in Fusan and in many other places every fifth day. On these the country people rely for all which they do not produce, as well as for the sale or barter of their productions. Practically there are no shops in the villages and small towns, their needs being supplied on stated days by travelling pedlars who form a very influential guild.

Turning away from the bustle of the main street into a narrow, dirty alley, and then into a native compound, I found the three Australian ladies who were the objects of my visit to this decayed and miserable town. Except that the compound was clean, it was in no way distinguishable from any other, being surrounded by mud hovels. In one of these, exposed to the full force of the southern sun, these ladies were living. The mud walls were concealed with paper, and photographs and other European knickknacks conferred a look of refinement. But not only were the rooms so low that one of the ladies could not stand upright in them, but privacy was impossible, invasions of Korean women and children succeeding each other from morning to night, so that even dressing was a spectacle for the curious. Friends urged these ladies not to take this step of living in a Korean town 3 miles from Europeans. It was represented that it was not safe, and that their health would suffer from the heat and fetid odors of the crowded neighborhood, etc. In truth it was not a “conventional thing” to do.

On my first visit I found them well and happy. Small children were clinging to their skirts, and a certain number of women had been induced to become cleanly in their persons and habits. All the neighbors were friendly, and rude remarks in the streets had altogether ceased. Many of the women resorted to them for medical help, and the simple aid they gave brought them much good-will. This friendly and civilizing influence was the result of a year of living under very detestable circumstances. If they had dwelt in grand houses 2¹⁄₂ miles off upon the hill, it is safe to say that the result would have been nil. Without any fuss or blowing of trumpets, they quietly helped to solve one of the great problems as to “Missionary Methods,” though why it should be a “problem” I fail to see. In the East at least, every religious teacher who has led the people has lived among them, knowing if not sharing their daily lives, and has been easily accessible at all times. It is not easy to imagine a Buddha or One greater than Buddha only reached by favor of, and possibly by feeing, a gate-keeper or servant.

On visiting them a year later I found them still well and happy. The excitement among the Koreans consequent on the Tong-hak rebellion and the war had left them unmolested. A Japanese regiment had encamped close to them, and, by permission, had drawn water from the well in their compound, and had shown them nothing but courtesy. Having in two years gained general confidence and good-will, they built a small bungalow just above the old native house, which has been turned into a very primitive orphanage.

The people were friendly and kind from the first. Those who were the earliest friends of the ladies are their staunchest friends now, and they knew them and their aims so well when they moved into their new house that it made no difference at all. Some go there to see the ladies, others to see the furniture or hear the organ, and a few to inquire about the “Jesus doctrine.” The “mission work” now consists of daily meetings for worship, classes for applicants for baptism, classes at night for those women who may not come out in the daytime, a Sunday school with an attendance of eighty, visiting among the people, and giving instruction in the country and surrounding villages. About forty adults have professed Christianity, and regularly attend Christian worship.

I mention these facts not for the purpose of glorifying these ladies, who are simply doing their duty, but because they fall in with a theory of my own as to methods of mission work.

There is a very small Roman Catholic mission-house, seldom tenanted, between the two Fusans. In the province of Kyöng-sang in which they are, there are Roman missions which claim 2,000 converts, and to promulgate Christianity in thirty towns and villages. There are two foreign priests, who spend most of the year in teaching in the provincial villages, living in Korean huts, in Korean fashion, on Korean food.

A coarse ocean with a distinct line of demarcation between the blue water of the Sea of Japan and the discoloration of the Yellow Sea, harsh, grim, rocky, brown islands, mostly uninhabited—two monotonously disagreeable days, more islands, muddier water, an estuary and junks, and on the third afternoon from Fusan the Higo Maru anchored in the roadstead of Chemulpo, the seaport of Seoul. This cannot pretend to be a harbor, indeed most of the roadstead, such as it is, is a slimy mud flat for much of the day, the tide rising and falling 36 feet. The anchorage, a narrow channel in the shallows, can accommodate five vessels of moderate size. Yet though the mud was en évidence, and the low hill behind the town was dull brown, and a drizzling rain was falling, I liked the look of Chemulpo better than I expected, and after becoming acquainted with it in various seasons and circumstances, I came to regard it with very friendly feelings. As seen from the roadstead, it is a collection of mean houses, mostly of wood, painted white, built along the edge of the sea and straggling up a verdureless hill, the whole extending for more than a mile from a low point on which are a few trees, crowned by the English Vice-Consulate, a comfortless and unworthy building, to a hill on which are a large decorative Japanese tea-house, a garden, and a Shinto shrine. Salient features there are none, unless the house of a German merchant, an English church, the humble buildings of Bishop Corfe’s mission on the hill, the large Japanese Consulate, and some new municipal buildings on a slope, may be considered such. As at Fusan, an English tide-waiter boarded the ship, and a foreign harbormaster berthed her, while a Japanese clerk gave the captain his orders.

Mr. Wilkinson, the acting British Vice-Consul, came off for me, and entertained me then and on two subsequent occasions with great hospitality, but as the Vice-Consulate had at that time no guest-room, I slept at a Chinese inn, known as “Steward’s,” kept by Itai, an honest and helpful man who does all he can to make his guests comfortable, and partially succeeds. This inn is at the corner of the main street of the Chinese quarter, in a very lively position, as it also looks down the main street of the Japanese settlement. The Chinese settlement is solid, with a handsome yamen and guild hall, and rows of thriving and substantial shops. Busy and noisy with the continual letting off of crackers and beating of drums and gongs, the Chinese were obviously far ahead of the Japanese in trade. They had nearly a monopoly of the foreign “custom”; their large “houses” in Chemulpo had branches in Seoul, and if there were any foreign requirement which they could not meet, they procured the article from Shanghai without loss of time. The haulage of freight to Seoul was in their hands, and the market gardening, and much besides. Late into the night they were at work, and they used the roadway for drying hides and storing kerosene tins and packing cases. Scarcely did the noise of night cease when the din of morning began. To these hard-working and money-making people rest seemed a superfluity.

The Japanese settlement is far more populous, extensive, and pretentious. Their Consulate is imposing enough for a legation. They have several streets of small shops, which supply the needs chiefly of people of their own nationality, for foreigners patronize Ah Wong and Itai, and the Koreans, who hate the Japanese with a hatred three centuries old, also deal chiefly with the Chinese. But though the Japanese were outstripped in trade by the Chinese, their position in Korea, even before the war, was an influential one. They gave “postal facilities” between the treaty ports and Seoul and carried the foreign mails, and they established branches of the First National Bank[5] in the capital and treaty ports, with which the resident foreigners have for years transacted their business, and in which they have full confidence. I lost no time in opening an account with this Bank in Chemulpo, receiving an English check-book and pass-book, and on all occasions courtesy and all needed help. Partly owing to the fact that English cottons for Korea are made in bales too big for the Lilliputian Korean pony, involving reduction to more manageable dimensions on being landed, and partly to causes which obtain elsewhere, the Japanese are so successfully pushing their cottons in Korea, that while they constituted only 3 per cent. of the imports in 1887, they had risen to something like 40 per cent. in 1894.[6] There is a rapidly growing demand for yarn to be woven on native looms. The Japanese are well to the front with steam and sailing tonnage. Of 198 steamers entered inwards in 1893, 132 were Japanese; and out of 325 sailing vessels, 232 were Japanese. It is on record that an English merchantman was once seen in Chemulpo roads, but actually the British mercantile flag, unless on a chartered steamer, is not known in Korean waters. Nor was there in 1894 an English merchant in the Korean treaty ports, or an English house of business, large or small, in Korea.

Just then rice was in the ascendant. Japan by means of pressure had induced the Korean Government to consent to suspend the decree forbidding its export, and on a certain date the sluices were to be opened. Stacks of rice bags covered the beach, rice in bulk being measured into bags was piled on mats in the roadways, ponies and coolies rice-laden filed in strings down the streets, while in the roadstead a number of Japanese steamers and junks awaited the taking off the embargo at midnight on 6th March. A regular rice babel prevailed in the town and on the beach, and much disaffection prevailed among the Koreans at the rise in the price of their staple article of diet. Japanese agents scoured the whole country for rice, and every cattie of it which could be spared from consumption was bought in preparation for the war of which no one in Korea dreamed at that time. The rice bustle gave Chemulpo an appearance of a thriving trade which it is not wont to have except in the Chinese settlement. Its foreign population in 1897 was 4,357.

The reader may wonder where the Koreans are at Chemulpo, and in truth I had almost forgotten them, for they are of little account. The increasing native town lies outside the Japanese settlement on the Seoul road, clustering round the base of the hill on which the English church stands, and scrambling up it, mud hovels planting themselves on every ledge, attained by filthy alleys, swarming with quiet dirty children, who look on the high-road to emulate the do-lessness of their fathers. Korean, too, is the official yamen at the top of the hill, and Korean its methods of punishment, its brutal flagellations by yamen runners, its beating of criminals to death, their howls of anguish penetrating the rooms of the adjacent English mission, and Korean too are the bribery and corruption which make it and nearly every yamen sinks of iniquity. The gate with its double curved roofs and drum chamber over the gateway remind the stranger that though the capital and energy of Chemulpo are foreign, the government is native. Not Korean is the abode of mercy on the other side of the road from the yamen, the hospital connected with Bishop Corfe’s mission, where in a small Korean building the sick are received, tended, and generally cured by Dr. Landis, who himself lives as a Korean in rooms 8 feet by 6, studying, writing, eating, without chair or table, and accessible at all times to all comers. The 6,700 inhabitants of the Korean town, or rather the male half of them, are always on the move. The narrow roads are always full of them, sauntering along in their dress hats, not apparently doing anything. It is old Fusan over again, except that there are permanent shops, with stocks-in-trade worth from one to twenty dollars; and as an hour is easily spent over a transaction involving a few cash, there is an appearance of business kept up. In the settlement the Koreans work as porters and carry preposterous weights on their wooden packsaddles.

FOOTNOTES:

[4] According to Mr. Hunt, the Commissioner of Customs at Fusan, in the Kyöng-sang province alone there are 17 such stations. Fusan is hedged round by a cordon of them within a ten-mile radius, and on the Nak-tong, which is the waterway to the provincial capital, there are four in a distance of 25 miles.

[5] Now the Dai Ichi Gingo.

[6] For latest trade statistics see appendix B.

CHAPTER II

FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF THE CAPITAL

Chemulpo, being on the island-studded estuary of the Han, which is navigable for the 56 miles up to Ma-pu, the river port of Seoul, it eventually occurred to some persons more enterprising than their neighbors to establish steam communication between the two. Manifold are the disasters which have attended this simple undertaking. Nearly every passenger who has entrusted himself to the river has a tale to tell of the boat being deposited on a sandbank, and of futile endeavors to get off, of fretting and fuming, usually ending in hailing a passing sampan and getting up to Ma-pu many hours behind time, tired, hungry, and disgusted. For the steam launches are only half powered for their work, the tides are strong, the river shallows often, and its sandbanks shift almost from tide to tide. Hence this natural highway is not much patronized by people who respect themselves, and all sorts of arrangements are made for getting up to the capital by “road.” There is, properly speaking, no road, but the word serves. Mr. Gardner, the British acting Consul-General in Seoul, kindly arranged to escort me the 25 miles, and I went up in seven hours in a chair with six bearers, jolly fellows, who joked and laughed and raced the Consul’s pony. Traffic has worn for itself a track, often indefinite, but usually straggling over and sterilizing a width enough for three or four highways, and often making a new departure to avoid deep mud holes. The mud is nearly bottomless. Bullock-carts owned by Chinese attempt the transit of goods, and two or three embedded in the mud till the spring showed with what success. Near Ma-pu all traffic has to cross a small plain of deep sand. Pack bulls, noble animals, and men are the carriers of goods. The redoubtable Korean pony was not to be seen. Foot passengers in dress hats and wadded white garments were fairly numerous.

The track lies through rolling country, well cultivated. There are only two or three villages on the road, but there are many, surrounded by fruit trees, in the folds of the adjacent low hills; stunted pines (Pinus sinensis) abound, and often indicate places of burial. The hillsides are much taken up with graves. There are wooden sign or distant posts, with grotesque human faces upon them, chiefly that of Chang Sun, a traitor, whose misdemeanors were committed 1,000 years ago. The general aspect of the country is bare and monotonous. Except for the orchards and the spindly pines, there is no wood. There is no beauty of form, nor any of those signs of exclusiveness, such as gates or walls, which give something of dignity to a landscape. These were my first impressions. But I came to see on later journeys that even on that road there can be a beauty and fascination in the scenery when glorified and idealized by the unrivalled atmosphere of a Korean winter, which it is a delight even to recall, and that the situation of Seoul for a sort of weird picturesqueness compares favorably with that of almost any other capital, but its orientalism, a marked feature of which was its specially self-asserting dirt, is being fast improved off the face of the earth.

From the low pass known as the Gap, there is a view of the hills in the neighborhood of Seoul, and before reaching the Han these, glorified and exaggerated by an effect of atmosphere, took on something of grandeur. Crossing the Han in a scow to which my chair accommodated itself more readily than Mr. Gardner’s pony, and encountering ferry boats full of pack bulls bearing the night soil of the city to the country, we landed on the rough, steep, filthy, miry river bank, and were at once in the foul, narrow, slimy, rough street of Ma-pu, a twisted alley full of mean shops for the sale of native commodities, of bulls carrying mountains of brushwood which nearly filled up the roadway; and with a crowd, masculine solely, which swayed and loafed, and did nothing in particular. Some quiet agricultural country, and some fine trees, a resemblance to the land of the Bakhtiari Lurs, in the fact of one man working a spade or shovel, while three others helped him to turn up the soil by an arrangement of ropes, then two chairs with bearers in blue uniforms, carrying Mrs. and Miss Gardner, accompanied by Bishop Corfe, Mr. M’Leavy Brown, the Chief Commissioner of Korean Customs, and Mr. Fox, the Assistant Consul, then the hovels and alleys became thick, and we were in extra-mural Seoul. A lofty wall, pierced by a deep double-roofed gateway, was passed, and ten minutes more of miserable alleys brought us to a breezy hill, crowned by the staring red brick buildings of the English Legation and Consular offices.

The Russian Legation has taken another and a higher, and its loftly tower and fine façade are the most conspicuous objects in the city, while a third is covered with buildings, some Korean and tasteful, but others in a painful style of architecture, a combination of the factory with the meeting-house, belonging to the American Methodist Episcopal Mission, the American Presbyterians occupying a humbler position below. A hill on the other side of the town is dedicated to Japan, and so in every part of the city the foreigner, shut out till 1883, is making his presence felt, and is undermining that which is Korean in the Korean capital by the slow process of contact.

One of the most remarkable indications of the change which is stealing over the Hermit City is that a nearly finished Roman Catholic Cathedral, of very large size, with a clergy-house and orphanages, occupies one of the most prominent positions in Seoul. The King’s father, the Tai-Won-Kun, still actively engaged in politics, is the man who, thirty years ago, persecuted the Roman Christians so cruelly and persistently as to raise up for Korea a “noble army of martyrs.”

I know Seoul by day and night, its palaces and its slums, its unspeakable meanness and faded splendors, its purposeless crowds, its mediæval processions, which for barbaric splendor cannot be matched on earth, the filth of its crowded alleys, and its pitiful attempt to retain its manners, customs, and identity as the capital of an ancient monarchy in face of the host of disintegrating influences which are at work, but it is not at first that one “takes it in.” I had known it for a year before I appreciated it, or fully realized that it is entitled to be regarded as one of the great capitals of the world, with its supposed population of a quarter of a million, and that few capitals are more beautifully situated.[7] One hundred and twenty feet above the sea, in Lat. 37° 34′ N. and Long. 127° 6′ E., mountain-girdled, for the definite peaks and abrupt elevation of its hills give them the grandeur of mountains, though their highest summit, San-kak-San, has only an altitude of 2,627 feet, few cities can boast, as Seoul can, that tigers and leopards are shot within their walls! Arid and forbidding these mountains look at times, their ridges broken up into black crags and pinnacles, ofttimes rising from among distorted pines, but there are evenings of purple glory, when every forbidding peak gleams like an amethyst with a pink translucency, and the shadows are cobalt and the sky is green and gold. Fair are the surroundings too in early spring, when a delicate green mist veils the hills, and their sides are flushed with the heliotrope azalea, and flame of plum, and blush of cherry, and tremulousness of peach blossom appear in unexpected quarters.

Looking down on this great city, which has the aspect of a lotus pond in November, or an expanse of overripe mushrooms, the eye naturally follows the course of the wall, which is discerned in most outlandish places, climbing Nam-San in one direction, and going clear over the crest of Puk-han in another, enclosing a piece of forest here, and a vacant plain there, descending into ravines, disappearing and reappearing when least expected. This wall, which contrives to look nearly as solid as the hillsides which it climbs, is from 25 to 40 feet in height, and 14 miles in circumference (according to Mr. Fox of H.B.M.’s Consular Service), battlemented along its entire length, and pierced by eight gateways, solid arches or tunnels of stone, surmounted by lofty gate houses with one, two, or three curved tiled roofs. These are closed from sunset to sunrise by massive wooden gates, heavily bossed and strengthened with iron, bearing, following Chinese fashion, high-sounding names, such as the “Gate of Bright Amiability,” the “Gate of High Ceremony,” the “Gate of Elevated Humanity.”

The wall consists of a bank of earth faced with masonry, or of solid masonry alone, and is on the whole in tolerable repair. It is on the side nearest the river, and onwards in the direction of the Peking Pass, that extra-mural Seoul has expanded. One gate is the Gate of the Dead, only a royal corpse being permitted to be carried out by any other. By another gate criminals passed out to be beheaded, and outside another their heads were exposed for some days after execution, hanging from camp-kettle stands. The north gate, high on Puk-han, is kept closed, only to be opened in case the King is compelled to escape to one of the so-called fortresses on that mountain.

Outside the wall is charming country, broken into hills and wooded valleys, with knolls sacrificed to stately royal tombs, with their environment of fine trees, and villages in romantic positions among orchards and garden cultivation. Few Eastern cities have prettier walks and rides in their immediate neighborhood, or greater possibilities of rapid escape into sylvan solitudes, and I must add that no city has environs so safe, and that ladies without a European escort can ride, as I have done, in every direction outside the walls without meeting with the slightest annoyance.

I shrink from describing intra-mural Seoul.[8] I thought it the foulest city on earth till I saw Peking, and its smells the most odious, till I encountered those of Shao-shing! For a great city and a capital its meanness is indescribable. Etiquette forbids the erection of two-storied houses, consequently an estimated quarter of a million people are living on “the ground,” chiefly in labyrinthine alleys, many of them not wide enough for two loaded bulls to pass, indeed barely wide enough for one man to pass a loaded bull, and further narrowed by a series of vile holes or green, slimy ditches, which receive the solid and liquid refuse of the houses, their foul and fetid margins being the favorite resort of half-naked children, begrimed with dirt, and of big, mangy, blear-eyed dogs, which wallow in the slime or blink in the sun. There too the itinerant vendor of “small wares,” and candies dyed flaring colors with aniline dyes, establishes himself, puts a few planks across the ditch, and his goods, worth perhaps a dollar, thereon. But even Seoul has its “spring cleaning,” and I encountered on the sand plain of the Han, on the ferry, and on the road from Ma-pu to Seoul, innumerable bulls carrying panniers laden with the contents of the city ditches.

The houses abutting on these ditches are generally hovels with deep eaves and thatched roofs, presenting nothing to the street but a mud wall, with occasionally a small paper window just under the roof, indicating the men’s quarters, and invariably, at a height varying from 2 to 3 feet above the ditch, a blackened smoke-hole, the vent for the smoke and heated air, which have done their duty in warming the floor of the house. All day long bulls laden with brushwood to a great height are entering the city, and at six o’clock this pine brush, preparing to do the cooking and warming for the population, fills every lane in Seoul with aromatic smoke, which hangs over it with remarkable punctuality. Even the superior houses, which have curved and tiled roofs, present nothing better to the street than this debased appearance.

The shops partake of the general meanness. Shops with a stock-in-trade which may be worth six dollars abound. It is easy to walk in Seoul without molestation, but any one standing to look at anything attracts a great crowd, so that it is as well that there is nothing to look at. The shops have literally not a noteworthy feature. Their one characteristic is that they have none! The best shops are near the Great Bell, beside which formerly stood a stone with an inscription calling on all Koreans to put intruding foreigners to death. So small are they that all goods are within reach of the hand. In one of the three broad streets, there are double rows of removable booths, in which now and then a small box of Korean niello work, iron inlaid with silver, may be picked up. In these and others the principal commodities are white cottons, straw shoes, bamboo hats, coarse pottery, candlesticks, with draught screens, combs, glass beads, pipes, tobacco-pouches, spittoons, horn-rimmed goggles, much worn by officials, paper of many kinds, wooden pillow-ends, decorated pillowcases, fans, ink-cases, huge wooden saddles with green leather flaps bossed with silver, laundry sticks, dried persimmons, loathsome candies dyed magenta, scarlet, and green, masses of dried seaweed and fungi, and ill-chosen collections of the most trumpery of foreign trash, such as sixpenny kerosene lamps, hand mirrors, tinsel vases, etc., the genius of bad taste presiding over all.

Plain brass dinner sets and other brass articles are made, and some mother-of-pearl inlaying in black lacquer from old designs is occasionally to be purchased, and embroideries in silk and gold thread, but the designs are ugly, and the coloring atrocious. Foreigners have bestowed the name Cabinet Street on a street near the English Legation, given up to the making of bureaus and marriage chests. These, though not massive, look so, and are really handsome, some being of solid chestnut wood, others veneered with maple or peach, and bossed, strapped, and hinged with brass, besides being ornamented with great brass hasps and brass padlocks 6 inches long. These, besides being thoroughly Korean, are distinctly decorative. There are few buyers, except in the early morning, and shopping does not seem a pastime, partly because none but the poorest class of women can go out on foot by daylight.

In the booths are to be seen tobacco pipes, pipestems, and bowls, coarse glazed pottery, rice bowls, Japanese lucifer matches, aniline dyes, tobacco-pouches, purses, flint and tinder pouches, rolls of oiled paper, tassels, silk cord, nuts of the edible pine, rice, millet, maize, peas, beans, string shoes, old crinoline hats, bamboo and reed hats in endless variety, and coarse native cotton, very narrow.

In this great human hive, the ordinary sightseer finds his vocation gone. The inhabitants constitute the “sight” of Seoul. The great bronze bell, said to be the third largest in the world, is one of the few “sights” usually seen by strangers. It hangs in a bell tower in the centre of the city, and bears the following inscription:—

“Sye Cho the Great, 12th year Man cha [year of the cycle] and moon, the 4th year of the great Ming Emperor Hsüan-hua [A.D. 1468], the head of the bureau of Royal despatches, Sye Ko chyeng, bearing the title Sa Ka Chyeng, had this pavilion erected and this bell hung.”

This bell, whose dull heavy boom is heard in all parts of Seoul, has opened and closed the gates for five centuries.