My Strange Rescue and Other Stories of Sport and Adventure in Canada

J. Macdonald Oxley

MY STRANGE RESCUE

AND OTHER STORIES

of Sport and Adventure in Canada

BY

J. MACDONALD OXLEY

Author of "In the Wilds of the West Coast," "Diamond Rock,"

"Up Among the Ice-Floes"

&c. &c.

THOMAS NELSON AND SONS

London, Edinburgh, and New York

1903

PREFATORY NOTE.

The Author begs to express his acknowledgments to the publishers of Our Youth, Youth's Companion, Harper's Young People, Golden Days, and other periodicals, in whose pages many of these stories and sketches were first published.

J. M. O.

CONTENTS.

MY VERY STRANGE RESCUE

A BLESSING IN STERN DISGUISE

IN PERIL AT BLACK RUN

TOUCH AND GO

THE CAVE IN THE CLIFF

TOBOGGANING

A MIC-MAC CINDERELLA

BLUE-NOSE FISHER FOLK

LOST ON THE LIMITS

A STRANGE HELPER

FORTY MILES OF MAELSTROM

THE CANADIAN CHILDREN OF THE COLD

FACE TO FACE WITH AN "INDIAN DEVIL"

IN THE NICK OF TIME

SNOW-SHOEING

THE SWIMMING MATCH AT THE ARM

HAROLD'S LASTING IMPRESSION

HOW WILBERFORCE BRENNAN VISITED WHITE BEAR CASTLE

OUTSIDE THE BOOM

FOUND AFTER MANY DAYS

MRS. GRUNDY'S GOBBLERS

ON THE WRONG SIDE OF THE SNOW-RIDGE

THROUGH THE TRACKLESS FOREST

WRECKS AND WRECKERS OF ANTICOSTI

A LUMBER CAMP

LACROSSE

A PILLOW-SLIP FULL OF APPLES

LOST ON LAKE ST. LOUIS

ICE-SKATING IN CANADA

THE WILD DOGS OF ATHABASCA

BIRDS AND BEASTS ON SABLE ISLAND

THE BORE OF MINAS BASIN

THE GAME OF RINK HOCKEY

ON THE EDGE OF THE RAPIDS

THEO'S TOBOGGANING TRIUMPH

MY VERY STRANGE RESCUE.

A shout of laughter rang through the kitchen and went echoing up the great chimney when, much more in fun than in earnest, I hinted that if they could not manage to kill the bear themselves I would have to do it for them.

Now it was no new thing for me to be laughed at. My big brothers were only too fond of that amusement, and I had got pretty well used to it; but this time I detected a particularly derisive tone in their hilarity, which touched me to the quick, and springing to my feet, with eyes flashing and cheeks burning, I burst out hotly,—

"I don't care how much you laugh. As sure as I'm standing here, I'll put a bullet in that bear before this time to-morrow night!"

At this they only laughed the louder, and filled the room with sarcastic shouts of,—

"Hurrah for the Bantam!"—"I'll bet on the bear"—"What will you take for his skin, Bantam?" until father silenced them with one of his reproving looks, and drew me to him, saying soothingly,—

"Don't mind the boys, Walter; and don't let your temper betray you into making rash vows that you cannot keep."

I sat down in the sulks, and soon after skipped off to bed; but it was a long time before I got to sleep, for my brain was in a whirl, and my blood coursing through my veins like fire.

I was the youngest in a family of six sturdy boys, and consequently came in for much more than a fair share, as I thought, of good-natured ridicule from my big brothers.

They were all fond enough of me, and generally very kind to me too; but they had a notion, and perhaps not altogether a mistaken one, that I was inclined to think too much of myself, and they took great pleasure in putting me down, as they were pleased to call it.

Of course I did my best not to be put down, and they had nicknamed me "the Bantam," as a sort of left-handed compliment to my fiery opposition against being put down.

I was rather small for my age, and they could easily beat me in nearly all the trials of skill and strength country boys delighted in—not quite all, however, for, much to my pride and satisfaction, I could hit the bull's-eye chalked out on the big barn-door twice as often as the best of them; and no small comfort did my skill in shooting give me.

But this far from contented me, and in my foolish feverish haste to get on a level with those big fellows, I was constantly attempting all sort of reckless, daring feats, that called forth my father's grave reproof and my mother's loving entreaties.

Time and again would father say to me,—

"Walter, your rashness will be the death of you some day. Don't be in such a hurry to be a man before you've quit being a boy!"

But reproof and entreaty alike went unheeded; and that night, as I tossed restlessly about in bed, I made solemn vows to the stars peeping in through the window that next morning I would take Tiger and go off alone after the huge black bear which had been prowling around the sheepfold lately, and which father and the boys had twice hunted in vain.

Soothed by the prospect of the glory success would bring me, I fell asleep, and dreamed that, armed only with my jack-knife, I was chasing hard after the bear, which seemed half as big as the barn, yet ran away in the most flattering fashion.

Next morning all my temper had vanished, and so much of my valour had vanished with it that my bear-hunting would never have probably got beyond dreamland had not Jack, the moment I appeared, called out mockingly,—

"Behold the mighty hunter! Make way for Bantam, the renowned bear-slayer."

The chorus of laughter that greeted this sally set me in a blaze again; but this time I held my tongue, and the teasing soon stopped.

The mischief was done, however; I felt as though I would rather die than go back on my word now. Never before in my life had I been stirred so deeply.

Determined to keep my purpose secret, I waited about the house until all the others had gone off. Then, quietly taking down my gun, I put half-a-dozen biscuits in my pocket, and, with well-filled powder-flask and bullet-pouch, slipped off unobserved towards the forest, Tiger following close at my heels.

Tiger was my own dog—a present from a city uncle after whom I had been named. He was half fox-hound, half bull-terrier, and seemed to combine the best qualities of both breeds, so that for sense, strength, and courage, his superior could not be found of his size. My affection for him was surpassed only by his devotion to me. He acknowledged no other master, and fairly lived in the light of my countenance.

This morning he evidently caught from my face some inkling of the serious nature of our business, for instead of bounding and barking about me in his wonted way he trotted gravely along at my side, every now and then looking up into my face, as though about to say, "Here I am, ready for anything!" And where could I have found a trustier ally?

It was a glorious day in December. A week of intense cold had been succeeded by a few days of milder weather, and over all the trees the frost had thrown a fairy garb of white that sparkled brightly in the morning sun. The air was just cold enough to be bracing. The spotless snow crunched crisply under my feet as I walked rapidly over it, and my spirits rose with every step.

Soon I had climbed the hill pasture, and with one look backward at my dear old home, nestling among its beeches and poplars in the plain below, I plunged into the dense undergrowth that bordered the vast Canadian forest, which stretched away inland for many a mile.

The snow lay pretty deep in the woods, but my snowshoes made the walking easy. Everywhere across the white surface ran the interlacing tracks of rabbits and red foxes, with here and there the broader, deeper print of the wild cat; for it had been a long, hard winter, and the wild animals, desperate with hunger, were drawing uncomfortably close to the settled districts.

As I pushed on into the lonely, silent forest, its shadows began to cool my ardour, and the inclination to turn back strengthened every moment, so that my pride had hard work to keep my courage up to the mark.

Presently I came to an open glade, almost circular, and about fifty yards across, walled in on all sides by tall, dark pines and sombre hemlocks.

It was so pleasant to be in full view of the sun again, that I halted on the verge of this glade to rest a little, leaning against a huge pine, and letting the sunshine pour down upon me, although my long walk had started the perspiration from every pore.

Tiger, who had been carefully scrutinizing every paw-print, but following up none, as he saw I evidently was not after small game that day, now bounded off along the edge of the forest, and I watched him proudly as, with nose close to the snow and tail high in the air, he ran hither and thither, the very picture of canine beauty and intelligence.

Suddenly he stopped short, snuffed fiercely at a track in the snow, and then, with sharp, eager barks that sounded like a succession of pistol-shots, and startled every nerve and fibre in my body into intense excitement, sprang over the snow with mad haste, until he brought up at the foot of a tree just opposite me on the other side of the glade.

For some moments I stood as if spell-bound. I felt that nothing less than a bear-trail could have put Tiger in such a quiver. Perhaps he had struck the track of the bear, about whose immense size father and the boys had talked so much.

I confess that at the thought my knees trembled, my tongue parched as though with hot thirst, and I stood there utterly irresolute, until all at once, like a great wave, my courage came back to me, the hunter instinct rose supreme over human weakness, and grasping my gun tightly, I hurried across to where the dog was still barking furiously.

A bare, blasted tree-trunk stood out gaunt and gray, in marked contrast to the dark masses of the pine and hemlock around. It was plainly the ruin of a magnificent pine, which once had towered high above its fellows, and then paid the penalty of its pre-eminence by being first selected as a target for the lightning.

Only some twenty feet of its former grandeur remained, and this poor, decapitated stub was evidently hollow and rotten to the roots, for deeply scored upon its barkless sides were the signs of its being nothing more or less than a bear's den—the admirably chosen hiding-place of some sagacious Bruin.

My gun was loaded with an extra charge of powder and two good bullets. I put on a fresh cap, made sure everything was in good order, and took my stand a few yards off from the tree to await the result of Tiger's audacious challenge.

Minute after minute crept slowly by, but not a sound came from the tree. The tension of nerve was extreme.

At length I could stand it no longer. If the bear was really inside the tree-trunk, I must know it immediately.

Looking up, I noticed that an adjoining hemlock sent out a long arm right over the hollow trunk, while a little above was another branch by which I could steady myself.

Taking off my snow-shoes, and laying my gun at the hemlock's foot, I climbed quickly up, Tiger for a time suspending his barking in order to look inquiringly after me.

Reaching the branch, which seemed strong enough for anything, I walked out on it carefully, balancing myself by the one above, my moccasined feet giving me a good foothold, until I was right over the deep, mysterious cavity.

I peered eagerly in, but of course saw nothing save darkness as of Egypt, and, half laughing at my own folly had turned to retrace my steps, when suddenly, without the slightest warning, the bough on which I stood snapped short off a few feet from the trunk.

For one harrowing instant I clung to the slender branch above, and then, it slipping swiftly through my fingers, with a wild shriek of terror I plunged feet foremost into the awful abyss beneath.

Just grazing the rim of the tree's open mouth, I fell sheer to the bottom, bringing up with such a shock that the fright and fall combined rendered me insensible.

How long I lay there I cannot say. When I did come to myself, my first impulse was to stand up. And words cannot express my relief when I found that, although much shaken up, no bones were broken, thanks to the accumulation of rotten wood at the bottom of this strange well.

But oh, what a fearful situation was mine, and how bitterly I reproached myself for my folly! Shut up in the heart of that hollow tree; four long miles from home and help; utterly unable to extricate myself, for the soft decayed sides of my prison forbade all attempts at ascent; only a few biscuits in my pocket; not a drop of water, and already I was suffering with thirst; and, to crown all, the possibility, ay, the certainty, of the bear returning in a few hours, while I had no other weapon of defence than the hunter's knife which hung at my belt.

Although it was mid-day now, intense darkness filled my prison cell, and the air was close and foul, for Bruin had evidently been tenant of the place all winter.

For some time I could do nothing but gaze at the little patch of blue sky above me that seemed so hopelessly far away, as if rescue must soon come from thence. I could faintly hear poor Tiger's barking still, and fearing he might go off in search of me, I kicked and pounded against the sides of the tree, shouting at the top of my voice.

I don't know whether he could hear me, but he did not go away at all events. It would have been far better for him, poor fellow, if he had.

After some minutes the first bewildering paroxysm of fright abated, and I set myself seriously to consider what was to be done. I could not give up all hope of escape, desperate as my case seemed, and I felt sure I would lose my mind if I did not keep myself constantly employed in some way.

There seemed but one thing to do, and to that I forthwith applied myself. In my belt hung my strong, keen-edged hunting-knife. Since I could not climb out of my prison, perhaps I could cut my way out. So drawing the knife, I set to work with tremendous vigour.

At first it was easy enough, for the soft decayed wood offered little opposition to my keen blade, and I felt encouraged. But presently I reached the hard rind, and then had to go warily for fear of snapping the steel off short.

The close confinement, the heavy, poisonous air, and the constrained position the work required, all told hard upon me; but I toiled away with the determination of despair.

I must have spent at least an hour thus, when, to my delight, a hard blow sent the knife-blade clean through the wood, and on drawing it back a blessed little bit of daylight peeped through, which made a new man of me.

At it I went again, and paused not this time until I had a jagged hole chipped out through which I could put my hand. If the bear did not come for a couple of hours more I would be free.

The moment I put out my hand Tiger caught sight of it, and came leaping up against the tree, wild with delight at finding me again, for now of course I could easily make him hear iny voice.

A few minutes' rest and the breathing of the pure, fresh air that streamed in through the opening, and chip, chip, chip, I cut away at the hard wood until a hole as big as my face was made.

Another brief rest, for I was getting very tired, when—ah, what is the matter? Why is Tiger barking so madly? Can it be that the bear is returning? Yes, there he comes!

He was half-way across the glade already, and Tiger, trembling with rage, was right below me at the root of the tree, ready to defend me to the death.

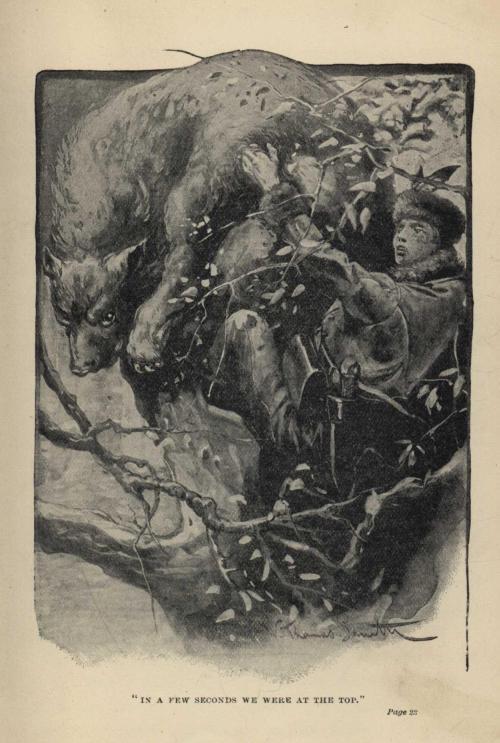

Growling fiercely, the huge brute shambled rapidly toward us. Another minute, and Tiger the dauntless sprang at his throat.

But the bear was too quick for him, and with one sweep of his great fore-paw sent his puny opponent rolling over on the snow.

Little hurt, and much wiser for this rebuff, the dog attacked from behind, and bit so sharp and quick that Bruin in self-defence, reared up on his hind legs, ready to wheel round and drop on the dog at the first opportunity.

For minutes (which seemed hours) the unequal contest went on before my straining eyes. More than once the bear, in sheer disgust at his inability to crush his agile adversary, attempted to climb the tree, and my heart seemed to stand still as his claws rattled against the wood. But the instant he turned his back Tiger had his sharp fangs deep into his hams, and with a fierce snarl down he dropped to renew the conflict.

The afternoon shades were lengthening now, and a new hope dawned within me. My mother had ere this grown anxious at my long absence from home, and perhaps my father and brothers were even then tracing me through the forest by my snow-shoe track. They would hear Tiger's furious yelps if they were anywhere within a mile of us. If my noble dog could hold out long enough we should both be saved.

Full of this hope I cheered him vigorously, and seeming to be as tireless as fearless, the little hero kept up the fight. They were both before me now in full view, and I could watch every movement. The scene would have been ludicrous if my life had not hung upon its issue—the bear was so clumsy and awkward, the dog so quick and clever.

As it was, I almost forgot my anxiety in my excitement, when, with a thrill of horror, I saw that Tiger's sharp teeth had caught in the bear's shaggy fur, and he could not free himself. The bear wheeled swiftly round upon him. One instant more, and the huge, pitiless jaws had him in their grasp at last.

There was an awful moment of silence, then a quick half-smothered cry, a harsh exultant roar, and out of that fatal embrace my brave, faithful dog dropped to the ground, a limp, lifeless mass.

I could think of nothing but my dog at first; and in frantic, futile rage I beat against the obdurate walls of my prison, while the bear sniffed curiously at his victim, turned him about with his great paws, and seemed to be exulting over the brave spirit he had conquered. But when, having satisfied his pride, the brute turned to climb the tree, all my thoughts centred upon myself, for I felt that my hour had come. I could feel his claws scraping against the outside as, wearied with his exertion, he climbed slowly up. There was nothing for me but to wait his coming, and then sell my life as dearly as possible.

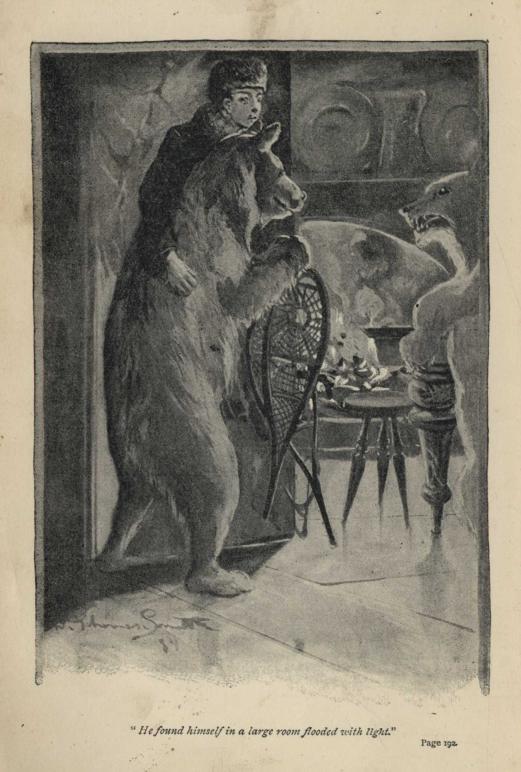

Firmly grasping my knife, whose keenness had, alas, been spent upon the tough wood, and feeling as though the bitterness of death were already past, I stood awaiting my fate. Watching closely the narrow opening at the top, I noticed that the bear was descending tail foremost. Foot by foot he came slowly down, striking his long, sharp claws deep into the spongy wood, his huge bulk completely filling the passage.

Not a movement or a sound did I make. All at once, as if by inspiration—was it in answer to my poor prayer?—an idea flashed into my brain, at which I grasped as a drowning man might grasp at a straw.

The bear was now close at my head. I waited until he had descended one step more, then reaching up both hands, and taking a firm grip of his soft, yielding fur, I shouted at the top of my voice.

For one harrowing moment the bear paused, as though paralyzed. Heaven help me if he drops, I thought. Then, with a wild spring, he started upward, dragging me after him. Putting forth all his vast strength he scrambled with incredible speed straight up that hollow shaft, I holding on like grim death, and giving all the help I could.

In a few seconds we were at the top, and with a joy beyond all describing I emerged into daylight. No sooner did the bear reach the rim than he swung himself over, and plunged headlong downwards without an instant's pause. At that moment I let go, and tried to make the descent more slowly; but the reaction was too great. My senses deserted me, and I tumbled in a heap at the foot of the tree. In that condition my father found me just before sunset; and although the deep snow had rendered my fall harmless, the strain and shock told so heavily upon me that many weeks passed before I was myself again, and I am not likely to ever forget the very strange way in which I was rescued by a bear.

A BLESSING IN STERN DISGUISE.

Bruno Perry's home was in about as lonely and unattractive a spot as one could well imagine; an unpleasant fact, the force of which nobody felt more keenly than did Bruno himself, for he was of a very sociable disposition and delighted in companionship. But, besides his father and mother, companions he had none, except his half-bred collie, Steeltrap, who had been given that name because of his sharpness, and who recognized no other master than Bruno, to whom he was unflaggingly devoted.

To find the Perry house was no easy task, for it lay away off from the main road on a little road of its own that was hardly better than a wood-path. Donald Perry was a very strange man. He was moody and taciturn by nature, and much given to brooding over real or fancied wrongs. Some years ago he had owned a fine farm not far from Riverton, but owing to a succession of disputes with his neighbours, about boundary-lines and other matters, he had in a fit of anger disposed of his farm and banished himself and his family to the wilderness, where he had purchased for a mere trifle the abandoned clearing of a timber-jobber.

Poor little Bruno, at that time only ten years old, cried bitterly as they turned their backs upon the pleasant home which he had come to love so dearly, and his mother joined her tears with his. But his father was not to be moved from his purpose. He had not much faith in or sympathy for other people's feelings, or "notions," as he contemptuously called them. The only notice he took of his wife and son in the matter was to gruffly bid them "stop blubbering;" and they both knew him too well not to do their best to obey.

That was full five years ago, and in all this time neither Bruno nor his mother had had any other society than their own, except an occasional deer-hunter or wood-ranger who might beg the favour of a night's lodging if he happened to find the farm-house after sundown.

"Oh, mother, are we always to live in this dreadful place?" exclaimed Bruno one day, when he knew his father to be well out of hearing. "I'm sure I'll go clean crazy if I don't get out of it soon. Father will have it that I must learn to run the farm, so as to take hold when he gives up. But I'll never be a backwoods farmer; I'd rather die first!"

"Hush, hush, my boy," said Mrs. Perry, in gentle reproof. "You must not talk that way. You don't mean what you say."

"Yes, I do, mother—mean every word of it," replied Bruno vehemently. "I'll run away if father won't let me go with his consent."

"And what would mother do without the light of her life?" asked Mrs. Perry tenderly, taking her son's curly head in both her hands and giving him a fond kiss on the forehead.

Bruno was silent for a moment, and then exclaimed petulantly,—

"Why couldn't you come too, mother?"

"Ah, no, boy," was the gentle response. "I will never leave my husband, even though my boy should leave me. But be patient yet a little while; be patient, Bruno. I don't think God intended you for a backwoods farmer, and if we only wait he will no doubt open a way for you somehow or other."

"Waiting's precious poor fun, mother," replied Bruno ruefully, yet in a tone that re-assured his mother, who, indeed, was always dreading lest her son's longing for the stir and bustle of city life should lead him to run away from the farm he so cordially disliked, leaving her to bear the double burden of unshared troubles and anxiety for her darling's welfare.

Bruno Perry was not a common country boy, rough, rude, and uncultivated. His mother had enjoyed a good education in her youth, and possessed besides a refined, gentle spirit that fitted her far better for the cultured life of the city than the rough-and-tumble existence to which the eccentricity of her husband had doomed her. Bruno had inherited much of her fine spirit, together with no small share of his father's deep, strong nature; and, thanks to his mother's faithful teaching and the wise use of the few books they had brought with them into the wilderness, was a fairly well educated lad. Every Saturday his father drove all alone to the nearest settlement and brought back with him a newspaper, which Bruno awaited with hungry eyes and eagerly devoured when at last it fell into his hands. By this means he knew a little, at all events, of the great world beyond the forest, and this knowledge maintained at fever-heat his desire to be in the midst of it. Only his deep affection for his mother kept him at home.

The summer just past had been an especially restless, uneasy time for Bruno. His blood seemed fairly on fire with impatience at his lot, and even the cool dark days of autumn brought no chill to his ardour. If anything, they made the matter worse; for the summer, with its bright sunny mornings, its delicious afternoon baths in the clear deep pool beyond the barn, and its long serene evenings, was not so hard to bear, even in the wilderness. Neither was the autumn, with its nutting forays, its partridge and woodcock shooting, and its fruit and berry expeditions, by any means intolerable. But the winter—the long, dreary, monotonous Canadian winter, when for week after week the mercury sank down below zero and rarely rose above it, when the cattle had to be fed and watered though the hands stiffened and the feet stung with bitter biting cold, while ears and cheek and nose were constantly being nipped by pitiless Jack Frost!—well, the long and short of it was that one night after Mr. Perry had gone off grimly to bed, looking much as if he were going to his tomb, leaving his wife and son sitting beside the big wood fire in the kitchen, Bruno drew his chair close to Mrs. Perry's, and, slipping his hand into hers, looked up into her sweet face with a determined expression she had never observed in him before.

"Mother," said Bruno, in low, earnest tones, "it's no use. This is the last winter I shall ever spend in this place. I can't and won't stand it any longer. Father may say what he likes, but he'll never make a farmer of me."

"What will you do, Bruno dear?" asked his mother gently, seeing clearly enough that it was no time for argument or opposition.

"Why, I'll go right into town and do something. I don't care what it is, so long as it's honest and it brings me bread and butter. I'd rather be a bootblack in town than stay out in this hateful place."

"But you hope to be something better than a bootblack, don't you, dearest?" questioned Mrs. Perry, with a sad smile, for she felt that the crisis in her boy's life had come, and that his whole future might depend upon the way she dealt with him now.

"Of course I do, mother," he answered, smiling in his turn. "But that will be better than nothing for a beginning, and something better will turn up after a while."

"Very well, Bruno, so be it. Of course it's no use beginning business as a bootblack in winter-time, when everybody is wearing overshoes. But when the spring mud comes then will be your chance, and perhaps before spring-time a better opening may present itself."

Bruno felt the force of his mother's clever reasoning, and with a quiet laugh replied,—

"All right, mother: I'll wait until spring as patiently as I can."

The afternoon following this conversation Bruno thought he would go into the forest and see if he could not get a shot at something, he hardly knew what. The snow lay deep upon the ground, so he strapped on his snow-shoes, and, with gun on shoulder and hatchet at belt, strode off into the woods. He was in rather an unhappy frame of mind, and hoped that a good long walk and the excitement of hunting would do him good. His father's clearing was not very large, and beyond its edge the great forest stretched away unbroken for uncounted leagues. Close at Bruno's heels ran the faithful Steeltrap, full of joy at the prospect of an afternoon's outing. The air was very cold, but not a breath of wind broke its stillness, and the only interruptions of the perfect silence were the crushing of the crisp snow beneath Bruno's broad shoes and the occasional impatient barks of his canine companion.

Climbing the hill that rose half a mile to the north from his home, Bruno descended the other side, crossed the intervening valley, where a brook ran gurgling underneath its icy covering, and ascended the ridge beyond, pushing further and further into the forest until he had gone several miles from the house. Then he halted and sat down upon a log for a rest. He had not been there many minutes before a sudden stir on the part of Steeltrap attracted his attention, and, looking up, he caught sight of a fine black fox gazing at him curiously for an instant ere it bounded away. As quick as a flash Bruno threw his gun to his shoulder, fired almost without taking aim, and to his vast delight the shot evidently took effect, for the fox, after one spasmodic leap into the air, went limping off, dragging a hind leg in a way that told clearly enough it was broken.

"After him, Steeltrap, after him!" shouted Bruno.

The dog needed no urging on. With eager bark he dashed after the wounded fox, Bruno following as fast as he could. Away went the three of them at the top of their speed, the boy just able to keep his quarry in sight, while Steeltrap was doing his best to get a good grip of his hindquarters so as to bring him to the ground. In this fashion they must have gone a good half mile when they came to a bear-trap, into which the fox vanished like a shadow, while Steeltrap, afraid to follow, contented himself with staying outside and barking vigorously.

On Bruno coming up he hardly knew what to do at first. Telling Steeltrap to watch the door, he examined the trap all round, and satisfied himself that there was no other way for the fox to get out. Then he made up his mind how to act.

"Ha, ha, my black beauty! You're not going to get off so easily as that," he said. And, kneeling down, he slipped off his snow-shoes and stood in his moccasined feet. Then, leaning his gun against the wall of the trap (which, I might explain, is built like a tiny log hut, having a heavy log suspended from the roof in such a way that on a bear attempting to enter it falls upon his back and makes him a prisoner). Bruno took his hatchet from his belt and proceeded to crawl into the trap, carefully avoiding the central stick which held up the loose log. It was very dark, but he could see the bright eyes of the fox as it crouched in the far corner. Holding his hatchet ready for a blow he approached the fox, and was just about to strike when, with a sudden desperate dart, it sprang past him toward the door. With an exclamation of anger Bruno turned to follow it, and in his hasty movement brushed against the supporting-post.

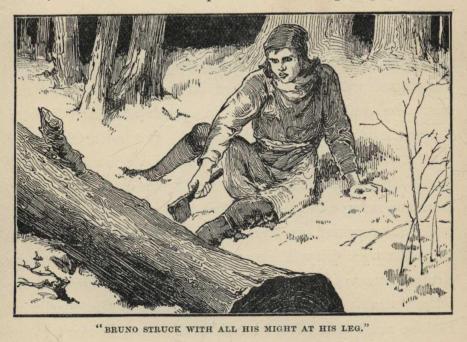

The mischief was done. In an instant the heavy log fell, and, although by a quick dodge to the left Bruno saved his shoulder, the ponderous thing descended upon his thigh, and, rolling down, pinned his right foot to the ground as firmly as if he had been the bear it was intended to capture.

Here, indeed, was a perilous situation for poor Bruno. Flat upon his back, with a huge log across his ankle, what was he to do? Sitting up he strove with all his might to push the log off, but he might as well have tried to move a mountain. He was fastened down beyond all hope of release without outside help.

But what hope was there of outside help? No one knew where he was, for he had not said anything to his mother when setting out, and his father had gone up the road some miles and would not return until dark. The one chance was that his father, on returning home, would miss him, and perhaps come in search of him, following the track made by his snow-shoes. But, even if he did, that could not be for hours yet, and in the meantime he would freeze to death; for the cold was intense, the thermometer being many degrees below zero.

An hour passed, an hour of pain and fruitless conjecture as to the possibility of rescue. As the evening drew near Bruno became desperate. He gave up all hope of his father reaching him in time, and came to the conclusion that he must either free himself or die; and he saw but one way of getting free. The log lay across his leg just above the ankle. His hatchet was near him. To chop the log away was utterly impossible, but it would be an easy thing to chop off the foot that it held so fast. Grasping the hatchet firmly in his right hand, Bruno hesitated for a moment, and then struck with all his might at his leg. A pang of awful agony shot through him, numbed as his nerves were with the cold. But, setting his teeth in grim determination, he struck blow after blow, heeding not the terrible suffering, until at length the bone snapped and Bruno was free.

Well-nigh fainting with pain, and weakness, the poor boy, on hands and knees, began the long and terrible journey homeward. His sufferings were beyond description; but life was very precious, and so long as he retained consciousness he would not give up the struggle.

Fortunately for him he had not gone more than a hundred yards over the cold hard snow before a bark from Steeltrap announced somebody's approach, and, just as Bruno fainted dead away, an Indian trapper, who, by the merest chance, had come to see if the trap had taken anything, came striding through the forest already dusky with the shadows of night. With a grunt of surprise he approached Bruno, turned him over gently, while Steeltrap sniffed doubtfully at his leggings; and then, recognizing the boy's face, and not waiting to investigate into the causes of his injury, he bound his sash about the bleeding stump, and throwing the senseless form over his broad shoulders, set out for the Perry house as fast as he could travel.

Not sparing himself the utmost exertion, he arrived there just as night closed in, and, pushing into the kitchen, deposited his burden upon the table, saying to Mrs. Perry, who came forward with frightened face,—

"Your boy, eh? Me find him 'most dead. Took him up right away, eh?"

When Mr. Perry returned, and beheld his son's pitiful and perilous condition, for once in his life he seemed moved. "I must take him in to the hospital in the city the first thing in the morning," said he. "He'll die if we keep him here."

And so it came about that, watched over by his parents, Bruno was next day carefully driven to the city, where by evening he was snugly ensconced in a comfortable cot in the big bright ward of the hospital.

He got well again, of course. So sturdy a lad was not going to succumb even to such injuries as he had suffered. But his foot was gone, and there was no replacing that. And yet in time he learned to look upon that lost foot as a blessing, for through it came the realization of all his desires. A boy with only one foot could not, of course, be a farmer, but he could be a clerk or something of that sort. Accordingly, through the influence of a relative in the city, Bruno, when thoroughly recovered, obtained a position in a lawyer's office as copying clerk. Some years later he was able to enter upon the study of the law. In due time he began to practise upon his own account, and with such success that he was ultimately honoured with a seat upon the bench as judge of the Supreme Court.

IN PERIL AT BLACK RUN.

There were four of them—Hugh, the eldest, tall dark, and sinewy, bespeaking his Highland descent in every line of face and figure; Archie, the second, short and sturdy, fair of hair and blue of eye, the mother's boy, as one could see at a glance; and then the twins, Jim and Charlie, the joy of the family, so much alike that only their mother could tell them apart without making a mistake—two of the chubbiest, merriest, and sauciest youngsters in the whole of Nova Scotia.

Squire Stewart was very proud of his boys; and looking at them now as they all came up from the shore together, evidently discussing something very earnestly, his countenance glowed with pride and affection.

When they drew near he hailed them with a cheery "Hallo, boys! what are you talking about there?"

Archie's face was somewhat clouded as he answered, in quiet, respectful tones, "Hugh and I were talking about going over to Black Run for a day's fishing, and Jim and Charlie want us to take them too."

"What do you think about it, Hugh?" asked the squire, turning to his eldest son.

"Well, it's just this way, sir," answered Hugh. "The little chaps will only be a bother to us, and perhaps get themselves into trouble. We can't watch them and watch our lines at the same time, that's certain."

"No, we won't," pleaded Jim, while Charlie seconded him with eager eyes. "We'll be so good."

"Oh, let them come," interposed Archie. "I'll look after them."

Hugh still seemed inclined to hold back; but the squire settled the matter by saying,—

"Take them with you this time, Hugh, and if they prove to be a bother they need not go again until they are old enough to take care of themselves."

"All right, sir! We'll take them.—But mind you, youngsters"—turning to the twins—"you must behave just as if you were at church."

Black Run was the chief outlet of the lake on which Maplebank, the Stewart house, was situated. Here its superabundance poured out through a long deep channel leading to a tumultuous rapid that foamed fiercely over dangerous rocks before settling down into good behaviour again. The largest and finest fish were sure to be found in or about Black Run. But then it was full six miles away from Maplebank, and an expedition there required a whole day to be done properly, so that the Stewart boys did not get there very often.

The Saturday to which all four boys were looking eagerly forward proved as fine as heart could wish, and after an early breakfast they started off. Hugh and Archie took the oars, the twins curled up on the stern-sheets, where their elder brother could keep his eye upon them, and away they went at a long steady stroke that in two hours brought them to their destination.

"Where'll be the best place to anchor, Hugh?" asked Archie, as he drew in his oars, and prepared to throw over the big stone that was to serve them as a mooring.

"Out there, I guess," answered Hugh, pointing to a spot about fifty yards above the head of the run.

"Oh, that's too far away; we won't catch any fish there," objected Archie, who was not at all of a cautious temperament. "Let's anchor just off that point."

Hugh shook his head. "Too close, I'm afraid, Archie. The current's awfully strong, you know, and we'd be sure to drift."

"Not a bit of it," persisted Archie. "Our anchor'll hold us all right."

But Hugh was not to be persuaded, and so they took up their position where he had indicated. They fished away busily for some time, the two elder boys using rods, and the twins simply hand-lines, until a goodly number of fine fish flapping about the bottom of the boat gave proof of their success. Still, Archie was not content. His heart was set upon fishing right at the mouth of the run, for he had a notion that some extra big fellows were to be caught there, and he continued harping upon the subject until at last Hugh gave way.

"All right, Archie. Do as you please. Here! I'll take the oars, and you stand on the bow, and let the anchor go when you're at the spot."

Delighted at thus gaining his point, Archie did as he was bidden, and with a few strong strokes Hugh directed the boat toward the run. So soon as they approached she began to feel the influence of the current, and Hugh let her drift with it. Archie was so engrossed in picking out the very best place that he did not notice how the boat was gathering speed until Hugh shouted,—

"Drop the anchor, Archie! What are you thinking about?"

Archie was standing in the bow, balancing the big stone on the gunwale, and the instant Hugh called he tumbled it over. The strong line to which it was attached ran swiftly out as the boat slipped down the run. Then it stopped with a sharp sudden jerk, for the end was reached, and the stone had caught fast between the big stones on the bottom.

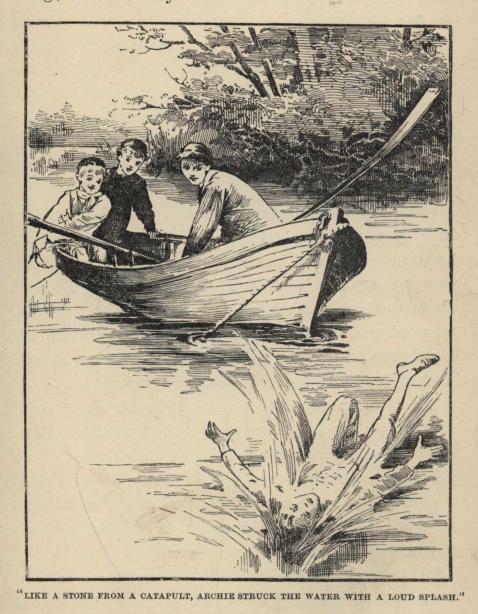

When the jerk came, Archie, suspecting nothing, was standing upright on the bow thwart, and at once, like a stone from a catapult, he went flying head-first through the air, striking the water with a loud splash, and disappearing into its dark embrace.

Hugh's first impulse was to burst out laughing, for he knew Archie could swim like a seal; and when, a moment later, his head appeared above the water, he hailed him gaily: "Well done, Arch! That was splendid! Come back and try it again, won't you?" while the twins laughed and crowed over their brother's amusing performance.

Archie was not disposed to take a serious view of the matter either, and shouted back, "Try it yourself. Come along; I'll wait for you."

When, however, he sought to regain the boat, he found the current too strong for him, and despite his utmost exertions, could make little or no headway against it. This would not have been a cause for much alarm, however, had not the banks of the run been lined with a dense growth of huge rushes through which Samson himself could hardly have effected a passage, while at their edge the water ran deep and swift. Moreover, it still had plenty of the winter chill in it, for the time was mid-spring.

Beginning to feel a good deal frightened, Archie called out, "You'll have to come and help me, Hugh. I can't get back to you."

Now unquestionably the proper thing for Hugh to have done was to take up the anchor, and letting the boat drift down to where Archie was, haul him on board. But strange to say, cool, cautious Hugh for once lost his head. His brother's pale, frightened face startled him, and without pausing to think, he threw off his coat and boots and leaped into the water, where a few strenuous strokes brought him to his brother's side.

The twins, in guileless innocence of any danger, thought all this great sport. Here were their two elder brothers having a swim without first taking off their clothes. They had never seen anything quite so funny before. They kneeled upon the stern-sheets, and leaned over the gunwale, and clapped their hands in childish ecstasy over what seemed to them so intensely diverting.

But to the two elder brothers it was very far from being diverting. When Hugh reached Archie he found him already half exhausted, and when, grasping him with his left hand, he strove to force him upward against the current, he realized that ere long he would be in the same condition himself. The strength of the current was appalling. The best that he could do, thus encumbered by Archie, was to keep from slipping downward. To make any headway was utterly impossible. Hoping that there might be, perhaps, a helpful eddy on the other side of the run, he made his way across, only to find the current no less powerful there. The situation grew more and more serious. The dense rushes defied all efforts to pierce them, and the boys were fain to grasp a handful of the tough stems, and thereby keep themselves from being swept away by the relentless current into the grasp of the fatal rapids, whose roar they could distinctly hear but a little distance below.

Hugh says that the memory of those harrowing moments will never lose its vividness. Blissfully unconscious of their brothers' peril, the twins laughed and chattered in the stern of the boat, their chubby faces beaming upon the two boys struggling desperately for life in the rushing water. Even in the midst of that struggle Hugh was thrilled with anxiety as he looked back at them lest they should lose their balance and topple over into the water, and he shouted earnestly to them,—

"Take care, Jim! Take care, Charlie!" whereat they both nodded their curly heads and laughed again.

Hugh was now well-nigh exhausted, and sorely divided in his mind as to whether he should stay by his brother and, perhaps, go down to death with him, or, leaving him in his desperate plight, struggle back to the boat, if that were possible, to prevent a like catastrophe to the twins. Poor fellow! it was a terrible dilemma for a mere lad.

Happily, however, he was spared the necessity of choosing either alternative. Suddenly and swiftly a boat shot out from the northern side of the run's mouth, and in it sat a brawny farmer, whose quick ear caught at once Hugh's faint though frantic shout for help.

"Hold on there, my lads; I'll get you in a minute," he shouted back. Sending his boat alongside that of the Stewarts', he quickly fastened his painter to it, and then dropped down the current until he reached the endangered boys. "Just in time, my hearties," said he cheerily. "Now, then, let me give you a hand on board;" and grasping them one after the other in his mighty arms, he lifted them over the side into his own boat.

Neither Hugh nor Archie was any the worse for their wetting, and the twins thought them even more funny-looking in their wet, bedraggled condition than they were in the water; but neither of them is nevertheless at all likely to forget, live as long as they may, the time they were in such peril at Black Run.

TOUCH AND GO.

All the oldest inhabitants of Halifax were of one mind as to its being the very coldest winter in their recollection. It really seemed as if some rash fellow had challenged Jack Frost to do his best (or worst) in the matter of cold, and Jack had accepted the challenge, with the result of making the poor Haligonians wish with all their hearts that they were inhabitants of Central Africa instead of the Atlantic coast of British America.

One reason why they felt the cold so keenly was that, owing to the situation of their city right on the edge of the ocean, with the great Gulf Stream not so very far off, their winters were usually more or less mild and broken.

But this particular winter was neither mild nor broken; on the contrary, it was both steady and severe. One frosty day followed another, each one dragging the thermometer down a few degrees lower, until at last a wonderful thing happened—so wonderful, indeed, that the already mentioned oldest inhabitants again were unanimous in assuring inquirers that it had happened only once before in their lives—and this was that the broad, beautiful harbour, after hiding its bosom for several days beneath a cloud of mist, called by seafaring folk the "barber," surrendered one night to the embrace of the Ice King, and froze over solidly from shore to shore.

Such a splendid sight as it made wearing this sparkling breastplate! Not a flake of snow fell upon it. From away down below George's Island, up through the Narrows, and into the Basin, as far as the eye could reach, lay a vast expanse of glistening ice, upon which the boys soon ventured with their skates and sleds, followed quickly by the men, and a day or two later horses and sleighs were driving merrily to and fro between Halifax and Dartmouth, as though they had been accustomed to it all their life. The whole town went wild over this wonderful event. No—not quite the whole town, after all, for there were some unfortunate individuals who had ships at their wharves that they wanted to send to sea, or expected ships from the sea to come in to their wharves, and they quite failed to see any fun in sleighing or skating where there ought to have been dancing waves.

If, however, some of the business men thought a frozen harbour an unmitigated nuisance, none of the boys who attended Dr. Longstrap's famous school were of the same mind. To them it was an unmixed blessing, and they were so carried away by its taking place that they actually had the hardihood to present a petition to the stern doctor begging for a week's holiday in its honour. And what is still more extraordinary, they carried their point to the extent of one whole day, with which unwonted boon they were fain to be content.

It was on this little anticipated holiday that the event took place which it is the business of this story to relate. Two of the most delighted boys at Dr. Longstrap's school were Harvey Silver and Andy Martin. They were great chums, being as much attached to each other as they were unlike one another in appearance. They lived in the same neighbourhood, were pretty much of the same age—namely, fourteen last birthday—went to the same school, learned the same lessons, and were fond of the same sports. But there the resemblance between them stopped. Andy was hasty, impetuous, and daring; Harvey was quiet, slow, and cautious. In fact, one was both the contrast and the complement of the other, and it was this, no doubt, more than anything else, which made them so attached to each other. Had their mutual likeness been greater, their mutual liking would perhaps have been less.

"Isn't it just splendid having a whole holiday to-morrow?" cried Harvey, enthusiastically, to his chum, as the crowd of boys poured tumultuously out of school for their morning recess, Dr. Longstrap having, with a grim smile, just announced that in view of the freezing of the harbour being such an extremely rare event, he had decided to grant them one day's liberty.

"We must put in the whole day on the harbour," responded Andy heartily. "Couldn't we take some lunch with us, and then we needn't go home in the middle of the day?"

"What a big head you have, to be sure!" exclaimed Harvey, with a look of mock admiration. "That's a great idea. We'll do it."

The following day was Thursday, and when the two boys opened their eyes after such a sleep as only tired healthy schoolboys can secure, they were delighted to find every promise of a fine day. The sun shone brightly, the air was clear, the wind was hushed, and everything in their favour. As Harvey, in the highest spirits, took his seat at the breakfast table, he pointed out the window, from which a full view of the harbour could be obtained. "Look, father," said he, "if there isn't the English mail steamer just coming round the lighthouse! There'll be no getting to the wharf for her to-day. What do you think they'll do?"

"Come up the harbour as far as they can, and then land the mails and passengers on the ice, I suppose," answered Mr. Silver.

"But how can she come up when it's all frozen?" queried Harvey.

"Easily enough. Ram her way through until it is thick enough to stop her."

"Oh, what fun that will be!" exclaimed Harvey. "How glad I am that we have a holiday to-day, so we can see it all!"

"Well, take good care of yourself, my boy, and be sure and be back before dark," said Mr. Silver.

When, according to promise, Andy Martin called for him soon after breakfast, Harvey dragged him to the dining-room window, and pointing out the steamer, now coming into the harbour at a good rate of speed, said gleefully,—

"There's the English mail steamer, Andy, and father says she'll ram her way up through the ice as far as she possibly can. Won't that be grand?"

Shortly after, the two boys left the house, and hastened off down Water Street until they reached a wharf from which they could easily get out upon the ice. They were both good skaters for their age, strong, sure, and speedy, and their first proceeding was to dart away across the harbour, spurting against one another in the first freshness of their youthful vigour, until they had reached the outer edge of the Dartmouth wharves. They then thought it was about time to rest a bit and regain their breath.

"What perfect ice!" gasped Andy. "It's ever so much better than fresh-water ice, isn't it?"

Harvey, being very much out of breath, simply nodded.

Andy was right, too. Whatever be the reason, the finest ice a skater can have is that which forms upon salt water. It has good qualities in which fresh-water ice is altogether lacking.

"Hallo, Andy! there's the steamer," cried Harvey suddenly, having quite recovered his wind.

Sure enough, just beyond George's Island the great dark hull of the ocean greyhound was discernible, as with superb majesty she solemnly pushed her way through the thin, ragged ice which marked where the current had been too strong for the breastplate to form properly. Full of impatience to watch the steamer's doings, the two boys hurried toward her at their best pace, so that in a few minutes they were not far from her bows, and as far out upon the ice as they thought it safe to venture.

No doubt it was a rare and thrilling sight, and not only the boys, but all who were upon the harbour at the time, gathered to witness it. The steamer was now in the thick, well-knitted ice, and could no longer force her way onward steadily, so she had to resort to ramming. Her course lay parallel to the wharves, and about one hundred yards or more from them. Reversing her engines, she would back slowly down the long narrow canal made in her onward progress until some hundreds of yards away; then coming to a halt for a moment, she would begin to go ahead, at first very slowly, almost imperceptibly, then gradually gathering speed as the huge screw spun round, sending waves from side to side of the ice-walled lane; faster and still faster, while the spectators, thrilling with excitement, held their breath in expectation; faster and still faster, until at last, with a crash that made even the steamer's vast frame tremble from stem to stern, the sharp steel bow struck the icy barrier, and with splintering sound bored its way fiercely through, but losing a little impetus with every yard gained, so that by the time the steamer had made her own length her onset was at an end, and sullenly withdrawing, she had to renew the attack.

As at the beginning, so at the end of the steamer's charge, there was a moment when she stood perfectly still. This was when all her impetus was exhausted, and for a brief second she paused before rebounding and backing away. During this almost imperceptible instant it was just possible for a swift skater to dart up and touch the bow as it towered above the ice hard pressed against it. There was absolutely nothing in such a feat except its daring. Yet—and perhaps for that very reason—there were those present rash enough to attempt it. Big Ben Hill, the champion speed skater, was the first, and he succeeded so admirably that others soon followed his example. Harvey and Andy were intensely interested spectators as one after another, darting up just at the right moment, touched with outstretched finger-tips the steamer's bow, and then, with skilful turn, swung safely out of the way.

"I'm going to try it too," said Andy, under his breath.

"You'll do nothing of the kind, Andy," answered Harvey. "It's just touch and go every time."

"Yes, I will. Buntie Boggs just did it, and if he can do it, I can," returned Andy eagerly.

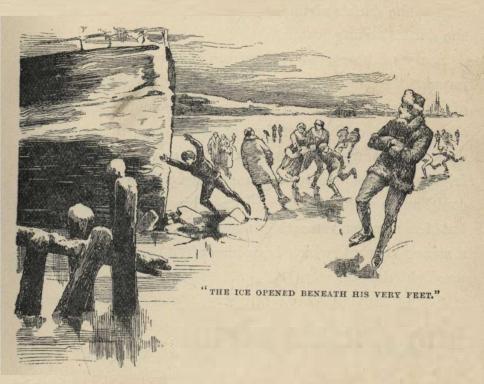

As he spoke, the steamer came gliding on for another charge. With eyes flashing, nerves tingling, muscles tense, and heart beating like a trip-hammer, Andy awaited her onset. Crash, crack, splinter; then pause—and like an arrow he flew at her bow. Harvey tried to hold him back, but in vain. Over the smooth ice he shot, and right up to the big black bow. With a smile of triumph he stretched out his hand, when—crash! the ice opened suddenly beneath his very feet, and he pitched headlong into the dark swirling water.

A cry of horror went up from the crowd, and with one impulse they moved as closely as they dared to the edge of the open water. There was a moment of agonized silence, then a shout of joy as a fur cap, followed by a dark body, emerged from the water, and presently Andy's frightened face was turned imploringly toward them. He could swim well enough, and keep himself afloat all right; but the steamer retreating along the narrow canal created a strong current, which bore him after her, and he was in no slight danger.

"Save him! oh, save him, won't you?" cried Harvey, grasping Ben Hill's arm imploringly.

"I will that, my lad; never fear."

But how was it to be done? All along the edge of the canal in which Andy was struggling for life, and for some yards from it, the ice was cracked and broken into jagged fragments, making it impossible for any one to approach near enough to the boy to help him out, and for the same reason he was unable to climb out by himself.

"A rope! a rope! I must have a rope!" shouted Ben Hill, looking eagerly around him. His quick eye fell upon a schooner lying at the head of a wharf near by.

"Cheer him up, boys," cried Ben; "I'll be back in a second;" and like a flash he sped off toward the schooner.

Almost in less time than it takes to tell it he reached her side, sprang over the low bulwarks on to the deck, snatched up a coil of rope that lay upon the cabin poop, leaped back to the ice, and with mighty strides came down toward the water, amid the cheers of the onlookers.

"Look out for yourself, Andy!" Ben shouted, as he drew close to the canal's edge, coiling the rope for a throw. "Now, then, catch!" and the long rope went swirling through the air.

A cry of disappointment from the crowd announced that it had fallen short.

"All right, Andy—better luck next time," called Ben, as he rapidly recovered the rope for another fling. Venturing a little nearer, and taking more pains, he flung it out with all his strength, and this time a shout of joy proclaimed that his aim had been true.

"Put it under your arms," called out Ben.

Letting go the cake of ice to which he had been clinging, Andy slipped the rope under his arms.

"Now, then, hold tight." And slowly, carefully, hand over hand, big Ben, with feet braced firmly and muscles straining, drew Andy through the broken cakes and up upon the firm safe ice. The moment he was out of danger a shout burst forth from the relieved spectators, and they crowded eagerly round rescued and rescuer.

"Out of the way there, please! out of the way!" cried Ben, as he gathered Andy's dripping form up in his arms. "This lad must be beside a fire as soon as possible."

Fortunately the crew were still on board the schooner from which the precious rope had been borrowed, and they had a fine fire in the cabin. Into this warm nook Andy was borne without delay. His wet clothes were soon stripped off, and he was turned into a bunk until dry ones could be procured. A messenger was despatched with the news to his home, and before long his mother, with feelings strangely divided between smiles and tears, drove down for the boy who had come so near to being lost to her for ever.

That evening, as Harvey and Andy were sitting by the fireside recounting for the tenth time the stirring incidents of the day, and voicing together the praises of big Ben Hill, Andy, with a sly twinkle of the eye, turned to Harvey, saying, "Do you remember saying to me that it was a touch and go every time?"

"Yes, Andy; what of it?"

"Well, I was just thinking that in my case I didn't touch, but I went—under the water, and I won't be in a hurry to try it again."

THE CAVE IN THE CLIFF.

"Say, Bruce, don't you think we could manage to put in a whole week up among the hills this autumn?" asked Fred Harris of Bruce Borden, as the two friends strolled along together one September afternoon through the main street of Shelburne, one of the prettiest towns upon the Nova Scotian sea-board.

"I guess so, Fred," responded Bruce promptly. "Father promised me a week's holiday to spend any way I chose if I stuck to the shop all summer, and I've been thinking for some time what I would do. That's a grand idea of yours. When would we go?"

"About the first of next month would be the best time, wouldn't it? We could shoot partridges then, you know, and there won't be any mosquitoes or black flies to bother us."

"All right, Fred. Count me in. I'm just dying for a shot at the partridges; and, besides, I know of a lake 'way up in the hills where there are more trout than we could catch in a year, and splendid big fellows, too! Archie Mack was telling me about it the other day."

"Why, that's the very place I wanted to go to; and it was Archie who told me about it, too," said Fred. "I'll tell you what, Bruce, we must get Archie to come with us, and then we'll have a fine time for sure."

"Hooray! You've got the notion now," cried Bruce with delight. "Archie's a splendid fellow for the woods, and he's such a good shot; he hardly ever misses. Why, I wouldn't mind meeting a bear if Archie was present."

"Ah, wouldn't you though, Mr. Bruce!" laughed Fred. "I guess if either you or I were to come across a bear he'd see more of our heels than our face. I know I wouldn't stop to make his acquaintance."

"I'll warrant Archie wouldn't run from any bear," said Bruce, "and I'm not so sure that I would either. However, there's small chance of our seeing one, so it's not much good talking about it. But I must run back to the shop now. Won't you come in after tea to-night, and we'll make our plans?"

Fred promised he would, and went on down the street, while Bruce returned to his place behind the counter; and if he was a little absent-minded in attending to the customers, so that he gave Mrs. White pepper instead of salt, and Mrs. M'Coy tea instead of coffee, we must not be too hard upon him.

Bruce Borden was the son of one of the most thriving shopkeepers in Shelburne, and his father, after letting him go to school and the academy until he was sixteen years of age, had then put an apron on him and installed him behind the counter, there to learn the management of the business, which he promised him would be Robert Borden and Son in due time if Bruce took hold of it in the right way. And Bruce did take hold. He was a bright, active, energetic lad, with a pleasant manner, and made an excellent clerk, pleasing his father so well that as the first year's apprenticeship was drawing to a close, Mr. Borden, quite of his own accord, made glad Bruce's heart by saying that he might soon have a whole week's holiday to do what he liked with, before settling down to the winter's work.

Bruce's friend, Fred Harris, as the son of a wealthy mill-owner who held mortgages on half the farms in the neighbourhood, did not need to go behind a counter, but, on the contrary, went to college about the same time that Bruce put on his apron. He was now at home for the vacation, which would not end until the last of October. He was a lazy, luxurious kind of a chap, although not lacking either in mind or muscle, as he had shown more than once when the occasion demanded it. Bruce and he had been playmates from the days of short frocks, and were very strongly attached to one another. They rarely disagreed, and when they did, made it up again as soon as possible.

In accordance with his promise, Fred Harris came to Mr. Borden's shop that same evening just before they were closing up, bringing Archie Mack with him; and after the shutters had been put on and everything arranged for the night, the three boys sat down to perfect their plans for the proposed hunting excursion to the hills.

Archie Mack bore quite a different appearance from his companions. He was older, to begin with, and much taller, his long sinewy frame betokening a more than usual amount of strength and activity, he had only of late come to Shelburne, the early part of his life having been spent on one of the pioneer farms among the hills, where he had become almost as good a woodsman as an Indian, seeming to be able to find his way without difficulty through what looked like trackless wilderness, and to know everything about the birds in the air, the beasts on the ground, or the fish in the waters. This knowledge, of course, made him a good deal of a hero among the town boys, and they regarded acquaintance with him as quite a privilege, particularly as, being of a reserved, retiring nature, like all true backwoodsmen, it was not easy to get on intimate terms with him. He was now employed at Mr. Harris's big lumber-mill, and was in high favour with his master because of the energy and fidelity with which he attended to his work.

"Now then, Fred, let's to business," said Bruce, as they took possession of the chairs in the back office. "When shall we start, and what shall we take?"

"Archie's the man to answer these questions," answered Fred. "I move that we appoint him commander-in-chief of the expedition, with full power to settle everything."

"You'd better make sure that I can go first," said Archie. "It won't do to be counting your chickens before they're hatched."

"Oh, there's no fear of that," replied Fred. "Father promised me he'd give you a week's holiday so that we could go hunting together some time this autumn, and he never fails to keep his promises."

"All right then, Fred, if you say so. I'm only too willing to go with you, you may be sure. So let us proceed to business," said Archie. And for the next hour or more the three tongues wagged very busily as all sorts of plans were proposed, discussed, accepted, or rejected, Archie, of course, taking the lead in the consultation, and usually having the final say.

At length everything was settled so far as it could be then, and, very well satisfied with the result of their deliberations, the boys parted for the night. As soon as he got home, Fred Harris told his father all about it, and readily obtained his consent to giving Archie a week's leave. There was, therefore, nothing more to be done than to get their guns and other things ready, and await the coming of the 1st of October with all the patience at their command.

October is a glorious month in Nova Scotia. The sun shines down day after day from an almost cloudless sky; the air is clear, cool, and bracing without being keen; the ground is dry and firm; the forests are decked in a wonderful garb of gold and flame interwoven with green whose richness and beauty defy description, and beneath which a wealth of wild fruit and berries, cherries, plums, Indian pears, blackberries, huckleberries, blueberries, and pigeon-berries tempts you at every step by its luscious largess. But for the sportsman there are still greater attractions in the partridges which fly in flocks among the trees, and the trout and salmon which Hash through the streams, ready victims for rod or gun.

Early in the morning of the last day in September the three boys set out for the hills. It would be a whole day's drive, for their waggon was pretty heavily loaded with tent, stove, provisions, bedding, ammunition, and other things, and, moreover, the road went up-hill all the way. So steep, indeed, were some of the ascents that they found it necessary to relieve the waggon of their weight, or the horse could hardly have reached the top. But all this was fun to them. They rode or walked as the case required; talked till their tongues were tired about what they hoped to do; laughed at Prince and Oscar, their two dogs—one a fine English setter, the other a nondescript kind of hound—as they scoured the woods on either side of the road with great airs of importance; scared the squirrels that stopped for a peep at the travellers by snapping caps at them; and altogether enjoyed themselves greatly.

Just as the evening shadows were beginning to fall they reached the farm on which Archie Mack's father lived, where they were to spend the night, and to leave their waggon until their return from camp. Mr. Mack gave them a hearty welcome and a bountiful backwoods supper of fried chicken, corn-cake, butter-milk, and so forth, for which they had most appreciative appetites; and soon after, thoroughly tired out, they tumbled into bed to sleep like tops until the morning.

"Cock-a-doodle-doo! Time to get up! Out of bed with you!" rang through the house the next morning, as Archie Mack, who was the first to waken, proceeded to waken everybody else.

"Oh dear, how sleepy I am!" groaned Fred Harris, rubbing his eyes, and feeling as though he had been asleep only a few minutes.

"Up, everybody, no time to waste!" shouted Archie again; and with great reluctance the other two boys, dragging themselves out on the floor, got into their clothes as quickly as they could.

Breakfast wras hurriedly despatched, and soon after, with all their belongings packed on an old two-wheeled cart drawn by a patient sure-footed ox, and driven by Mr. Mack himself, the little party made their way through the woods to their camping-ground, which was to be on the shore of the lake Archie had been telling them about. Without much difficulty they found a capital spot for their tent. Mr. Mack helped them to put it up and get everything in order, and then bade them good-bye, promising to return in six days to take them all back again.

The first four days passed away without anything of special note happening. They had glorious weather, fine fishing, and very successful shooting. They waded in the water, tramped through the woods, ate like Eskimos, and slept like stones, getting browner and fatter every day, as nothing occurred to mar the pleasure of their camp out. On the afternoon of the fourth day they all went off in different directions, Fred taking Prince the setter with him, Bruce the hound Oscar, and Archie going alone. When they got back to camp that evening Bruce had a wonderful story to tell. Here it is in his own words:—

"Tell you what it is, fellows, we've a big contract on hand for to-morrow. You know that run which comes into the lake at the upper end. Well, I thought I'd follow it up and see where it leads to; so on I went for at least a couple of miles till I came to a big cliff. I felt a little tired, and sat down on a boulder to rest a bit. Oscar kept running around with his nose at the ground as if he suspected something. All of a sudden he stopped short, sniffed very hard, and then with a loud, long howl rushed off to the cliff, and began to climb a kind of ledge that gave him a foothold. I followed him as best I could; but it wasn't easy work, I can tell you. Up he went, and up I scrambled after him, till at last he stopped where there was a sort of shelf, and at the end of it a big hole in the rock that looked very much like a cave. He ran right up to the hole and began to bark with all his might. I went up pretty close, too, wondering what on earth Oscar was so excited about, when, the first thing I knew, one bear's head and then another poked out of the hole, and snarled fiercely at Oscar. I tell you, boys, it just made me creep, and I didn't wait for another look, but tumbled down that ledge again as fast as I could and made for camp on the dead run. It was not my day for bears."

"You're a wise chap, Bruce," said Archie, clapping him on the back. "You couldn't have done much damage with that shot-gun, even if you had stayed to introduce yourself. I'm awfully glad you've found the cave. Father told me about these bears, and said he'd give a sovereign for their tails. There's an old she-bear and two half-grown cubs. I guess it was the cubs you saw. The old woman must have been out visiting."

"If I'd known that they were only cubs I might have tried a dose of small shot on them," said Bruce regretfully.

"It's just as well you didn't," answered Archie. "We'll pay our respects to them to-morrow. I'll take my rifle, and you two load up with ball in both barrels, and then we'll be ready for business."

So it was all arranged in that way, and then, almost too excited to sleep, the three lads settled down for the night, which could not be too short to please them.

They were up bright and early the next morning, bolted a hasty breakfast, and then proceeded to clean and load their guns with the utmost care. Fred and Bruce each had fine double-barrelled guns, in one barrel of which they put a bullet, and in the other a heavy load of buckshot. Archie had his father's rifle, and a very good one it was, which he well knew how to use. Besides this each carried a keen-bladed hunting-knife in his belt.

Thus armed and accoutred they set forth full of courage and in high spirits. They had no difficulty in finding and following Bruce's course the day before, for Oscar, who seemed to thoroughly understand what they were about, led them straight to the foot of the cliff, and would have rushed right up to the cave again if Archie had not caught him and tied him to a boulder. Then they sat down to study the situation. For them to go straight up the ledge with the chance of the old bear charging down upon them any moment would be foolhardy in the extreme. They must find out some better way than that of besieging the bears' stronghold.

"Hurrah!" exclaimed Archie, after studying the face of the cliff earnestly. "I have it! Do you see that ledge over there to the left? If we go round to the other side of the cliff we can get on that ledge most likely, and it'll take us to right over the shelf where the cave is. We'll try it, anyway."

Holding Oscar tight, they crept cautiously around the foot of the cliff, and up at the left, until they reached the point Archie meant. There, sure enough, they found the ledge two sharp eyes had discovered, and it evidently led over toward the cave just as he hoped. Once more tying the dog, who looked up at them in surprised protest, but was too well trained to make any noise, the boys made their way slowly along the narrow ledge, until at last they came to a kind of niche from which they could look straight down upon the shelf, now only about fifteen feet below them.

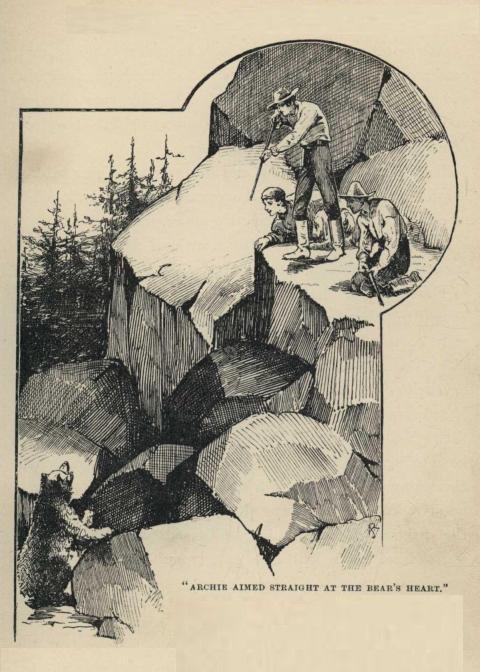

"Splendid, boys!" whispered Archie, gripping Fred's arm. "We're as safe as a church-mouse here, and they can't poke their noses out of the cave without our seeing them."

Keeping very still and quiet, the boys waited patiently for what would happen. Then, getting tired of the inaction, Bruce picked up a fragment of rock and threw it down upon the ledge below, where it rattled noisily. Immediately a deep, fierce growl came from the cave, and a moment afterwards the old bear herself rolled out into the sunshine.

"The top of the morning to you, missus!" called out Archie saucily. "And how may your ladyship be feeling this morning?"

At the sound of his voice the bear turned quickly, and catching sight of the three boys in such close proximity to the privacy of her home, uttered a terrible roar of rage, and rearing up on her hind legs, strove to climb the piece of cliff that separated them from her.

Bruce and Fred, who had never seen a wild bear before, shrank terror-stricken into the corner, but Archie, looking as cool as a cucumber, stood his ground, rifle in hand.

"No, no, my lady; not this morning," said he, with an ironical bow. "You're quite near enough already."

Foiled in her first attempt, the great creature gathered herself together for another spring, and once more came toward them with a savage roar. As she did so her broad, black breast was fully exposed. Without a tremor of fear or excitement Archie lifted his rifle to his shoulder and aimed straight at the bear's heart; a sharp report rang out through the clear morning air, followed close by a hideous howl of mingled rage and pain; and when the smoke cleared away the boys, with throbbing hearts, looked down upon a huge black shape that writhed and struggled in the agonies of death. A simultaneous shout of victory burst from their lips and gave relief to their excited emotions.

"Hurrah, Archie! You've done for her," cried Fred, clapping him vigorously on the back.

"Yes. I reckon she won't have any more mutton at father's expense," said Archie with a triumphant smile. "Just look at her now. Isn't she a monster?"

In truth she was a monster; and even though the life seemed to have completely left her, the boys thought it well to wait a good many minutes before going any nearer. After some time, when there could be no longer any doubt, they scrambled down the way they came, and, unloosing Oscar, approached the cave from the front. Oscar bounded on ahead with eager leaps, and catching sight of the big black body, rushed furiously at it. But the moment he reached it he stopped, smelled the body suspiciously, and then gave vent to a strange, long howl that sounded curiously like a death lament. After that there could be nothing more to fear; so the three boys climbed up on the shelf and proceeded to examine their quarry. She was very large, and in splendid condition, having been feasting upon unlimited berries for weeks past.

"Now for the cubs," said Archie. "The job's only half done if we leave these young rascals alone. I'm sorry they're too big to take alive. Ha, ha! Oscar says they're at home."

Sure enough the hound was barking furiously at the mouth of the cave, which he appeared none too anxious to enter.

"Bruce, suppose you try what damage your buckshot would do in there," suggested Archie.

"All right," assented Bruce, and, going up to the mouth, he peered in. Two pairs of gleaming eyes that were much nearer than he expected made him start back with an exclamation of surprise. But, quickly recovering himself, he raised his gun and fired right at the little round balls of light. Following upon the report came a series of queer cries, half-growls, half-whimpers, and presently all was still.

"I guess that did the business," said Bruce.

"Why don't you go in and see?" asked Archie.

"Thank you. I'd rather not; but you can, it you like," replied Bruce.

"Very well, I will," said Archie promptly, laying down his gun. And, drawing his hunting-knife, he crawled cautiously into the cave. Not a move or sound was there inside. A little distance from the mouth he touched one soft, furry body from which life had fled, and just behind it another. The buckshot had done its work. The cubs were as dead as their mother. The next thing was to get them out. The cave was very low and narrow, and the cubs pretty big fellows. Archie crawled out again for a consultation with the others. Various plans were suggested but rejected, until at length Archie called out,—

"I have it! I'll crawl in there and get a good grip of one of the cubs, and then you fellows will catch hold of my legs and haul us both out together."

And so that was the way they managed it, pulling and puffing and toiling away until, finally, after tremendous exertion, they had the two cubs lying beside their mother on the ledge.

"Phew! That's quite enough work for me to-day," said Fred, wiping the perspiration from his forehead.

"For me too!" chorused the others.

"I move we go back to camp and wait there until father comes with his cart, and then come up here for the bears," said Archie.

"Carried unanimously!" cried the others, and with that they all betook themselves back to camp.