A Clerk of Oxford and His Adventures in the Barons' War

Evelyn Everett-Green

The Project Gutenberg eBook, A Clerk of Oxford, by Evelyn Everett-Green

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/clerkofoxfordhis00ever |

A Clerk of Oxford

and

His Adventures in the Barons' War

By E. EVERETT-GREEN

Author of "Shut In," "In Taunton Town," "The Sign of the Red Cross,"

"In the Days of Chivalry," "The Lost Treasure of Trevlyn." &c. &c.

T. NELSON AND SONS

London, Edinburgh, and New York

1898

The City of Oxford from an old print.

CONTENTS.

| I. | THE DIE CAST | 9 |

| II. | A RIVER JOURNEY | 25 |

| III. | OLD OXFORD | 40 |

| IV. | THE FIRST DAY | 55 |

| V. | THE NEW LIFE | 70 |

| VI. | A "MAD" PARLIAMENT | 85 |

| VII. | THE CONSTABLE'S CHILDREN | 100 |

| VIII. | STORMY SCENES | 116 |

| IX. | A STUDENTS' HOLIDAY | 131 |

| X. | THE FAIR OF ST. FRIDESWYDE | 147 |

| XI. | THE MAGICIAN'S TOWER | 163 |

| XII. | WINTER DAYS WITHIN THE CASTLE | 178 |

| XIII. | KENILWORTH CASTLE | 193 |

| XIV. | THE GREAT EARL | 208 |

| XV. | PRINCE EDWARD | 223 |

| XVI. | BACK AT OXFORD | 239 |

| XVII. | THE BELL OF ST. MARTIN'S | 254 |

| XVIII. | THE NEW CHANCELLOR | 269 |

| XIX. | THE CHANCELLOR'S AWARD | 285 |

| XX. | TURBULENT TIMES | 300 |

| XXI. | KING AND STUDENTS | 315 |

| XXII. | IN ARMS | 328 |

| XXIII. | ON THE FIELD OF LEWES | 344 |

| XXIV. | AFTER THE BATTLE | 360 |

| XXV. | CHRISTMAS AT KENILWORTH | 375 |

| XXVI. | PLOTS | 391 |

| XXVII. | THE CAPTIVE A CONQUEROR | 407 |

| XXVIII. | THE FATAL FIGHT | 423 |

| XXIX. | LEOFRIC'S REWARD | 439 |

| XXX. | ON THE STILL ISIS | 454 |

A CLERK OF OXFORD.

CHAPTER I.

THE DIE CAST.

"My son," spoke a gentle voice from behind the low, moss-grown wall, "we must not mourn and weep for those taken from us, as if we had no hope."

Face downwards upon the newly-made mound of earth lay a youth of some fifteen or sixteen summers. His slight frame was convulsed by the paroxysm of his grief; from time to time a strangled sob broke from his lips. The kindly-faced monk from the Priory hard by had been watching him for some time before he thus addressed him. Probably he now saw that the violence of the outburst was spent.

The youth started upon hearing himself addressed, and as he sprang to his feet he revealed a singularly attractive face. The brow was broad and massive, indicating intellectual power. The blue eyes beneath the pencilled arch of the delicate eyebrows looked out upon the world with a singular directness and purity of expression. The features were finely cut, and there were strength and sweetness both in the curved, thoughtful lips, and in the square outline of the jaw. The fair hair clustered in curling luxuriance about his head, and fell in sunny waves to his shoulders. His hands were long and white, and looked rather as though they had wielded pen than weapon or tool of craftsman. Yet the lad's habit was that of one occupying a humble rank in life, and the shoes on his feet were worn and patched, as though by his own apprentice hands. Beside him lay a wallet and staff, upon which the glance of the monk rested questioningly. The youth appeared to note the glance, yet it was the words addressed to him that he answered.

"I think it is rather for myself I weep, my father. I know that they who die in faith rest in peace and are blessed. But for those who are left—left quite alone—the world is a hard place for them."

Father Ambrose looked with kindly solicitude at the lad. He noted his pale face, his sunken eyes, the look of weary depression that seemed to weigh him down, and he asked gently,—

"What ails thee, Leofric, my son?"

"Everything," answered the youth, with sudden passion in his tones. "I have lost everything in the world that I prized. My father is dead. I have no home. I have no fortune. All that we had is swallowed up in paying for such things as were needful for him while he lay ill. Even that which he saved for masses for his soul had to go at the last. See here, my father, I have but these few silver pieces left in all the world. Take them, and say one mass for him, and let me kneel at the door of the chapel the while. Then will I go forth into the wide world alone, and whether I live or die matters nothing. I have no one in the wide world who will know or care."

But the monk gently put back the extended hand, and laid his own kindly upon the head of the youth.

"Keep thy money, my son. The mass shall be said—ay, and more than one—for the repose of thy father's soul. He was a good man and true, and I loved him well. That pious office I will willingly perform in memory of our friendship. But now, as to thyself. Whither goest thou, and what wilt thou do? I had thought that thou wouldst have come to me ere thou didst sally forth into the wide world alone."

There was a faint accent of reproach in the monk's voice, and Leofric's sensitive face coloured instantly.

"Think it not ingratitude on my part, my father," he said quickly. "I was coming to say good-bye. But that seems now the only word left to me to speak in this world."

"Wherefore so, my son? why this haste to depart? The old life has indeed closed for thee; but there may be bright days in store for thee yet. Whither art thou going in such hot haste?"

"I must e'en go where I can earn a living," answered Leofric, "and that must be by the work of mine own hands. I shall find my way to some town, and seek to apprentice myself to some craft. These hands must learn to wield axe or hammer or mallet. There is nothing else left for the son of a poor scholar, who could scarce earn enough himself to feed the pair of us."

Father Ambrose looked at the lad's white fingers, and he slightly shook his head.

"Methinks thou couldst do better with those hands, Leofric. Hast never thought of what I have sometimes spoken to thee, when thou hast been aiding me with the care of the parchments?"

The lad's face flushed again quickly; but his eyes met the gaze fastened upon his with the fearless openness which was one of their characteristics.

"My father, I could not be a monk," he said. "I have no call—no vocation."

"Yet thou dost love a quiet life of meditation? Thou dost love learning, and hast no small store for thy years. It is a beautiful and peaceful life for those who would fain flee from the trials and temptations of the world. And the Prior here thinks well of thee; he has never grudged the time I have spent upon thee. I shall miss thee when thou art gone, Leofric; life here is something too calm and same."

There was a touch of wistful regret in the father's tones which brought back the ready tears to Leofric's eyes. After his own father, he owed most to this kindly old monk, though it had never for a moment struck him that the teaching and training of a bright young lad had been one of the main interests in that monotonous existence.

"That is what I have felt myself," he answered quickly. "I love the calm and the quiet, the books and the parchments. I shall bless you every day of my life for all your goodness to me. But I would fain see the great world too. I have heard my father and others speak of things I would fain see with mine own eyes. It breaks my heart to go, yet I cannot choose but do so. I dare not ask to come to you, my kindest friend, my second father. I could not be a monk. I should but deceive and disappoint you were I to seek an asylum with you now."

Father Ambrose sighed slightly as he shook his head; but he made no attempt to influence the youth. Perhaps he loved him too well to press him to enter upon a life which had so many limitations and drawbacks.

Yet he would not let him go forth upon his travels with so small a notion of what lay before him. He led him into the refectory, where strangers were entertained, and had food brought and set before him. The lad was hungry, for he had of late undergone a very considerable mental strain, and had had little enough time or thought to spare for creature comforts. The long illness of his father, a man gently born, but of very narrow means, had completely worn him out in body and mind; and now, when thrown penniless upon the world, there had seemed nothing before him but to wander forth with wallet and staff, and seek some craftsman who would give him food and shelter whilst he served a long and perhaps hard apprenticeship to whatever trade he chanced upon.

He spoke again of this as he sat in the refectory, and again Father Ambrose shook his head.

"Thou art not of the stuff for an apprentice to some harsh master; thou hast done but little hard work. And think of thy skill with brush and pen, and thy knowledge of Latin and the Holy Scriptures; thy sweet voice, and thy skill upon the lute. What will all these serve thee, if thou dost waste thy years of manhood's prime at carpenter's bench or blacksmith's forge?"

Leofric sighed, and asked wistfully,—

"Yet what else can I do, my father?"

"Hast ever thought of Oxford?" asked Father Ambrose, rubbing his chin reflectively. "There be lads as poor as thou that beg their way thither and live there as clerks, being helped thereto by the gifts of pious benefactors. They say that the King's Majesty greatly favours students and clerks, and that a lad who can sing a roundelay or turn an epigram can earn for himself enough to keep him whilst he wins his way to some honourable post. Hast ever thought of the University, lad? that were a better place for thee than a craftsman's shop."

Leofric's eyes brightened slowly whilst the monk spoke. Such an idea as this had never crossed his mind heretofore. Living far away from Oxford, and hearing nothing of the life there, he had never once thought of that as a possible asylum for himself; but in a moment it seemed to him that this was just the chance he had been longing for. He could not bring his mind to the thought of the life of the cloister; yet he loved learning and the fine arts with a passionate love, and had received just enough training to make him ardently desire more.

"Would such a thing as that be possible for such as I, my father?" he asked with bated breath, seeming to hang upon the monk's lips as he waited for the answer.

"More than possible—advisable, reasonable," answered another voice from the shadows of the room. Leofric started to his feet and bent the knee instinctively; for, unseen to both himself and Father Ambrose, the Prior had entered, and had plainly heard the last words which had passed between the pair.

The Prior was a tall, venerable man, with eagle eye and an air of extreme dignity; but he was kindly disposed towards Leofric, and greeted him gently and tenderly, speaking for a few minutes of his recent heavy loss, and then resuming the former subject.

"Oxford is the place where lads such as thou do congregate together in its many schools and buildings, and learn from the lips of the instructed and wise the lore of the ancients and the wisdom of the sages. There be many masters and doctors there who began life as poor clerks, begging alms as they went. What one man has done another may attempt. Thou mayest yet be a worthy clerk, and rise to fame and learning."

"Without money?" asked Leofric, whose eyes began to sparkle and glow.

"Yes, even without money," answered the Prior: "for at Oxford there are monasteries and abbeys to each of which is attached a Domus Dei; and there are gathered together poor clerks and other indigent persons, to whom an allowance of daily food is made from the monks' table; whilst, through the liberality of benefactors, a habit is supplied to them yearly, together with such things as be absolutely needful for their support. Once was I the guest of the Abbot of Osney, and I remember visiting the Domus Dei, and seeing the portions of meat sent thither from the refectory. I will give thee a letter of recommendation to him, good lad. It may be that this will serve thee in some sort upon thy arrival."

Leofric bent the knee once more in token of the gratitude his faltering lips could scarce pronounce. The thought of a life of study, in lieu of that of an apprentice, was like nectar to him. Prior and Father alike smiled at his boyish but genuine rapture.

"Yet think not, my son, that the life will be free from many a hardship, to a poor clerk without means and without friends. There be many wild and turbulent spirits pent within the walls of Oxford. Men have lost life and limb ere now in those brawls which so often arise 'twixt townsmen and clerks. The Chancellor doth all he can to protect the lives of scholars and clerks; yet, do as he will, troubles ofttime arise, and men have ere this been forced to leave the place by hundreds till the turbulent citizens can be brought to reason and submission."

But Leofric was in nowise daunted by this aspect of the case. Trained up hardily, albeit of studious habits, the fear of hardships did not daunt him.

"So long as I have food to eat and raiment to wear, I care for no hardship, so as I may become a scholar," he said. "And can I, reverend Father, rise to the dignity of a master, if I do not likewise take the vows of the Church upon me?"

"Ay, truly thou canst," was the reply. "There are the scholastic Trivium of grammar, logic, rhetoric, and the mathematical Quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. These form the magic circle of the arts, of which thou mayest become a master without taking any vow to Holy Church. Yet methinks thou wouldest do well to wear the tonsure and the gown, that thou mayest in all quarrels or troubles have the right to claim the benefit of clergy, and so escape from the secular arm if it were stretched out against thee. This is the usual custom of clerks at Oxford and Cambridge. But it commits thee to nought, if thou art not willing to join thyself to any of our brotherhoods."

The Prior eyed him kindly, but Father Ambrose sighed, and Leofric himself felt a qualm of shame at his own distaste for the life of the cloister.

"The wish, the call, may come perchance," he answered humbly, glancing from one to the other; "but methinks I am not fit for the life of holy meditation, or surely the kindness I have here received would have inclined mine heart that way."

"Thou art still too young to take such vows upon thyself," said the Prior. "It is men who come to us aweary of the evils and strife of the world that know the blessedness of the cloistered life. Thou mayest learn that lesson in time; or thou mayest link thy lot with that of these wandering friars, who teach men that they have found the more acceptable way. For myself, I have found the place of rest, and I desire to end my days here in peace."

"And how may I journey from here to Oxford?" asked Leofric with some timidity, after a short silence. "Surely the way is long; and I have never fared farther than Coventry, which place I thought to make my home, if I could but find a master who would receive me as apprentice."

The Prior pondered awhile before replying.

"There be two ways of journeying—by land and by water," he replied; "if by land, thou wouldest have to beg thy way from place to place. At some hostel they would give thee bed and board, most like, if thou wouldest make them merry by a song; or at some great house, if thou couldst recite a ballad or speak a Latin grace. At the Monasteries thou wouldest receive food and bed, and mayhap an alms to help thee on thy way. Many a clerk begs his way to Oxford year by year, and is well received of all. Yet the perils of the way are many and great through the forests which lie betwixt thee and thy goal. It might be that the water way would be the better."

"I love the water," said Leofric eagerly; "and my little canoe lies beneath the bank under the alder clump. I have made many a miniature voyage in her before. Methinks she would carry me safely did I but know the way."

"And the way thou canst not miss," answered the Prior. "This little stream which flows past our walls joins itself, as thou dost know, to the wider Avon, which presently flows into a river men call the Cherwell, and in its turn that doth make junction with the Isis, whereon the town of Oxford is situate. This junction is hard by the town itself; when thou dost reach that, thy journey will have an end."

Leofric listened eagerly. He had heard, indeed, of these things, but hitherto they had been but names to him. Now it seemed as though the great unknown world, lying without the circle of his daily life, were about to open before him.

"I would fain try the water way," he said. "I am skilful with the paddle; and I can carry my little craft upon my back whenever rocks and rapids impede my progress. The season is favourable for the journey. The ice and snow are gone. There is a good depth of water in all the streams, and yet the weed and slime of summer and autumn have not begun to appear; nor will the overarching boughs from the trees hinder progress as they do when clad in their summer bravery. I love the river in the early spring, and if I do but follow the course of the stream I cannot miss my way, as I might well do upon the road in the great forest tracks."

"Yes, that is very true. Methinks thou wilt be safer so, if thou canst find sustenance upon the way. But thou canst carry with thee some provision of bread, and there be several godly houses beside the river where thou wilt be welcomed by the brothers, who will supply thy needs. Take, too, thy bow and arrows; thou wilt doubtless thus secure some game by the way. But have a care in the King's forests around Oxford how thou dost let fly thy shafts. Many a man has lost his life ere now for piercing the side of some fat buck."

Leofric's heart was now all on fire for the journey which lay before him. He could scarcely believe that but one short hour ago he had believed himself hopelessly doomed to a life of uncongenial toil. He had never thought of this student life—he hardly knew of its existence; but the Prior of the Monastery and some of the monks, who had known and befriended both Leofric and his father, had themselves discussed several times the question of dispatching the youth to Oxford for tuition; and the rather unexpected death of the father, after a lingering illness, seemed to open the way for the furtherance of this design.

Leofric had been the pet of the Monastery from his childhood. Always of a studious turn, and eager for information, it had been the favourite relaxation of several of the monks to instruct him in the Latin tongue, to teach him the art of penmanship, and even to initiate him into some of the mysteries of that wonderful illumination of parchments which was the secret of the monks in the Middle Ages.

Leofric profited by every opportunity afforded him. Already he could both speak and understand Latin easily. He had a very fair knowledge of certain portions of the Scriptures, and possessed a breviary of his own, which he regarded as his greatest treasure. For the age in which he lived these were accomplishments of no mean order, and it would have seemed to the ecclesiastics little short of a disgrace to them had they permitted their pupil to lose his scholarship in some craftsman's shop. They had frequently spoken of sending him as a clerk to Oxford, unless he could see his way to becoming one of themselves. This, however, was not to be. The boy, though reverent and devout, had no leanings after the life of the cloister, and the Prior was too wise a man to put pressure upon him. But he was willing to forward, by such means as he could, any project which should secure to Leofric the advantages of a liberal education.

So the lad was bidden to remain a guest of the Monastery for the few days necessary to his simple preparations. The Prior wished him to be provided with a habit suitable to his condition of clerk. This habit was made of a strong sort of cloth, and reached to the knees, being confined at the waist by a leather girdle. He was also provided with a change of under-raiment, with strong leggings and shoes, and with a supply of coarse bread and salted meat sufficient for several days. The Prior wrote a letter to the Abbot of Osney, recommending the lad to his favourable notice, and asking for him a place in the Domus Dei, should no better lodging be obtainable.

Leofric himself spent his time in the mending of his canoe, which had been somewhat battered by the winter storms. He had made the little craft out of the bark of trees, and had covered it with pitch to make it waterproof. Some story he had heard about wild men in unknown lands had given him the idea of constructing this little boat, and now it seemed as though it would be of real service to him in his new career.

Father Ambrose would sit beside him on the river bank, and talk to him as he prosecuted this task. There was a strong bond of affection between the old monk and the young lad.

"Thou wilt come back some day and see us, Leofric," he said once, as the task drew near to its accomplishment; "I would fain look again upon thy face before I die."

"Indeed I will, father. I too shall always love this place, and shall never forget the kindness I have received, nor how these many days masses have been said for my father, and never a penny paid by me, albeit I would gladly give my all."

"Nay, nay, boy, it is a labour of love; and we know that thou wilt some day, when thou art rich and famous, give of thine abundance to our shrine here. Thou wilt see strange things in the great world, my son. Thou wilt see the great ones of the earth rising up against their anointed King, and that King taking vows upon his lips which he has neither the wish nor the intention to fulfil. The world is full of terrible things, and thou wilt quickly see many of them. Yet keep through all a pure heart and clean hands, so will God love thee, be thy path what it will."

Leofric looked up quickly.

"I have heard somewhat from time to time of the feud betwixt the King and the Barons; but to me such tales are but as idle words. I know not what men mean."

"Thou wilt know more anon," answered the monk gravely. "We have heard from those who pass to and fro that times are dangerous, and men's minds full of doubt and fear. I know not what may betide this land, but there be those who say that the sword will ere long be unsheathed, and that brother will war against brother as it hath not been seen for many a long day. God forbid that such things should be!"

"And will such strife come nigh to Oxford?" asked Leofric. "Shall we hear ought there of the battle and the turmoil?"

"I trow well that ye will. Knowest thou not that the King hath a palace close by the walls of the city, and another but a few leagues away? Methinks that in yon city there will be much strife of tongues anent these burning questions of which we scarce hear a whisper. Thou must seek to be guided aright, my son; for youth is ever hot-headed, and like to be carried away by rash counsels. It is a grievous thing for a nation to rise against its anointed head; and yet, even as Saul was set aside by God, and another put in his place, we may not always say that a King can do no wrong—albeit we must be very slow to judge and condemn him."

Leofric listened eagerly. Every day of late he had heard words which roused within him the knowledge that beyond the peaceful circle of his past life lay a seething world into which he was shortly to plunge. The thought filled him with eager longings and desires. He wanted to shoot forth in his tiny craft and see this world for himself. And, behold, to-day his task was finished, and the Prior had ordained that at dawn upon the morrow he should go.

His habit and provision were already packed and stowed away. He had received his letter and messages, and had listened in meek silence to the admonitions and instructions of the Prior. He had slept his last night beneath the hospitable Monastery roof, and had heard mass for the last time in the grey dawning.

Now he stood with one foot in his little craft, pressing the hand of Father Ambrose, and looking round at the familiar faces and buildings with smiles and tears struggling for mastery in his face.

Then the canoe shot out into the midst of the stream.

His voyage was begun.

CHAPTER II.

A RIVER JOURNEY.

It was no light task that Leofric had set himself. The river wound in and out through forest tracts hardly ever traversed. Trees blown down in winter storms lay right athwart the stream. Débris brought down from above was often packed tight against such obstructions; and then there was no way of proceeding save by dragging up the canoe out of the water and launching it again lower down. As the forest was often very thick and tangled along the banks of the river, this was no light matter, and had Leofric not been gifted with a strong will and a very resolute purpose, he might well have given up in despair.

As it was, he found travelling a great deal slower work than he had anticipated, and already his store of provision was greatly diminished, although he could not flatter himself that he had travelled any very great distance. He was sometimes disposed to doubt whether, after all, he had been wise in choosing the waterway in preference to the road.

Night was falling, and it looked as though rain was likely to come on at moonrise. The clouds were sullen and lowering; the wind moaned and whistled through the trees, and lashed the water into angry little wavelets. Leofric was feeling weary and a little depressed by the intense loneliness of his voyage, when suddenly he heard himself hailed by a friendly voice from somewhere out of the thicket.

"Whither away, good friend, and why art thou afloat and alone at this hour of the evening? What dost thou in yon frail craft out on the darkling river?"

Leofric looked eagerly about him, and espied, not far away, a ruddy-faced youth of about his own age, sitting beside the water fishing, with a basket at his side that showed he had not thus sat in vain. With a few strokes of his paddle he brought himself alongside the bank. The sound of a human voice was as music to his ears after the long silence of the forest.

"Good-even, good comrade," he answered, stepping lightly ashore; "and welcome indeed is thy friendly voice. For four days have I been alone upon this river, and the sight of a kindly face is like a draught of new wine."

"But what dost thou alone upon the river?"

"Marry, that is soon told. I am a poor lad who would fain become a clerk, and I am on my way to Oxford, there to seek to maintain myself whilst I study the arts and win my way to a livelihood—"

Hardly had he got out these words before the other youth sprang to his feet with a whoop of joy, and to Leofric's astonishment flung his arms about his neck, and fairly danced in the exuberance of his delight.

"Now, what ails thee?" he asked, half amused, half bewildered. "Hast thou taken leave of thy senses, good friend?"

"Thou mayest well ask—methinks it must even seem so; but listen, fair youth, and soon shalt thou understand. I am the son of a farmer, but I, too, have a great longing after letters. I have heard of this same city of learning, and I have begged and prayed of my father, who has many other sons, to let me fare forth and find my way thither, and climb the tree of learning. At first he listened not, but laughed aloud, as did my brothers. But my mother took my part, and I learned to read last winter at the Monastery, and the kindly fathers spoke well of my progress. Through these winter days I have gone daily thither, taking an offering of fish, and receiving instruction from them—"

"That is how I obtained such learning as I possess," interposed Leofric eagerly; "and my father taught me too, for he was a scholar of no mean attainments. But it is the monks who possess the books and parchments."

"Yea, verily; and these last weeks I have mastered in some poor sort the art of penmanship. And now my father has almost consented to letting me go. Only he has said that I must wait until chance shall send me a companion for the way. From time to time there pass by clerks and scholars returning to Oxford after an absence, or making their way thither, even as thou art doing; and my father has promised that I may join myself to the next of these who shall pass by. Now thou dost understand why I did so embrace thee. For if thou wilt have me for a travelling companion, we may e'en start forth to-morrow, and find ourselves in Oxford ere another week be passed."

No proposition could have been more welcome to Leofric. He had had enough of loneliness, and this sturdy farmer's son would be the best possible comrade for him. He was delighted at the notion. His canoe would carry the double burden, and the fatigues of navigation would be greatly lessened when shared between two.

"Come up to the farm with me," cried his new friend, "and there will be bed and board and a hearty welcome for thee; thou shalt find there a better lodging than in some hollow tree by the river-banks; and my mother will give us provision enow ere we start forth upon our voyage to-morrow."

Leofric was grateful indeed for this invitation. He made fast his canoe, saw that his few possessions were safely protected from a possible wetting, and followed his new friend along the narrow winding track which led from the river-side to the clearing round the farmstead.

On the way he learned that his companion's name was John Dugdale—commonly called Jack. The farm where he had lived all his life was situated not more than five miles from the town of Banbury. Jack had plainly heard more of the news of the world than had reached Leofric in his quiet home on the upper river. Something of the stir and strife that was agitating the kingdom had penetrated even to this lonely farm.

The great Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort, had passed through Banbury on his way from Kenilworth to London, not long ago. There was a great stir amongst the people, Jack told Leofric, and men spoke of the Earl as a saviour and deliverer, and he was received with something very like royal honours when he appeared. Leofric asked what it was from which he was to deliver the people, and Jack was not altogether clear as to this; but it had something to do with the exactions of the King and the Pope; and he was almost certain that the clergy themselves were as angry with the King as the Barons could be. He had heard it said that half the revenue of the realm was being taken to enrich the coffers of the Pope, or to aid him in his wars. More than that Jack could not say, rumours of so many kinds being afloat.

"But let us once get to Oxford, good comrade, and we shall soon learn all this, and many another thing besides. I want to know what the world is saying and thinking. I am weary of being stranded here like a leaf that has floated into some backwater and cannot find the channel again. I want to know these things; and if there be stirring times to come for this land, as many men say there will, I would be in the forefront of it all. I would wield the sword as well as the pen."

This was a new idea to Leofric, who had contented himself hitherto with dreams of scholastic distinction, without considering those other matters which were exercising the ruling spirits of his day. Jack's words, however, brought home to him the consciousness that there would be other matters of interest to engross him, once let him enter upon the life of a rising city. Oxford could not but be a centre of vitality for the whole kingdom. Once let him win his way within those walls, and a new world would open before his eyes.

Talking eagerly together, the lads pursued their way through the forest path, and suddenly emerged upon the clearing where the farmhouse stood. Lights shone hospitably from door and window; a barking of dogs gave a welcome to the son of the house; and Leofric speedily found himself pushed within a great raftered kitchen, lighted by the blaze of a goodly fire of logs, where he was quickly surrounded by friendly faces, and welcomed heartily, even before Jack had told all his tale and explained who the stranger was.

The Dugdales were honest farmer folks, always glad to welcome a passing stranger, and to hear any item of news he might come furnished with. Leofric had little enough of this commodity; but the fact that he was making his way to Oxford as a prospective clerk there was a matter of much interest to this household. Farmer Dugdale was a man of his word. He had promised Jack to let him go so soon as he should find a companion to travel with. He would have preferred as companion one who had had previous experience of University life; but he would not go back on his word on that account. Leofric's handsome and open face and winning manner gained him the good-will of all at the farm: they pressed him to remain their guest for a few days, whilst Jack's mother made her simple preparations for sending out her boy into the world for an indefinite time, and the two companions learned to know each other better.

Leofric was willing enough to do this. He was very happy amongst these hearty, homely people, and became attached to all of them, especially to Jack. Together they strengthened the canoe, made a locker in which to stow away sufficient provision for the journey, and a second paddle for Jack to wield, which he quickly learned to do with skill and address.

Jack's mother took Leofric to her motherly heart at once, and she made sundry additions to his scanty stock of clothing, seeing that his equipment equalled that of her own son. It was little enough when all was said and done; for times were simple, and luxuries unknown and undreamed of, save in the houses of great nobles. The boys felt rich indeed as they beheld their outfits made ready for them, and there was quite a feast held in their honour upon the last evening ere they launched forth upon their long journey.

Happy as Leofric had been at the farm, he was still conscious of a thrill of pleasure when he and Jack dipped their paddles and set forth upon their journey together. The Dugdale family, assembled on the banks, gave them a hearty cheer. They answered by an eager hurrah, and then, shooting round a bend in the stream, they found themselves alone on the sparkling waterway.

To Leofric this voyage was very different from the last. There were the same obstacles and difficulties to be overcome, but these seemed small now that they were shared between two. Jack was strong, patient, and merry. He made light of troubles and laughed at mishaps. They fared sumptuously from the well-stocked larder of the farm, and the weather was warm and sunny. To make a bed of leaves in some hollow tree, and bathe in the clear, cold river on awaking, was no hardship to either lad. They declared they did not mind how long the journey lasted, save for the natural impatience of youth to arrive at a given destination.

"And I should like an adventure," quoth Jack, "ere we sight the walls and towers of Oxford Castle. Men talk of the perils of travel; but, certes, we have seen nothing of them. I've had more adventure tackling a great pike in the stream at home sometimes than we have seen so far."

Nevertheless Jack was to have his wish, and the travellers were to meet with an adventure before they reached their journey's end.

It came about in this wise.

They knew that they must be drawing near their journey's end. They had been told by a woodman, whose hut had given them shelter upon the last night, that the forest and palace of Woodstock were near at hand. They wanted to get a view of that royal residence. So upon the day following they halted soon after mid-day, and leaving their canoe securely hidden in some drooping alder bushes, they struck away along a forest track described to them by the woodman, which would, if rightly followed, conduct them to a hill from whence a view could be obtained of the palace.

Walking was tedious and difficult, and they often lost their way in the intricacies of the forest; but still they persevered, and were rewarded at last by a partial view of the place, which was a finer building than either of the lads had ever seen before. But the sun was getting low in the sky by this time, and they had still to make their way back to their boat, unless they were to sleep supperless in the forest; so they did not linger long upon the brow of the hill, but quickly retraced their steps through the forest, trying to keep at least in the right direction, even though they might miss the actual path by which they had come.

Suddenly they became aware of a tumult going on in a thicket not very far away. They heard the sound of blows, of cries and shouts—then of oaths and more blows. Plainly there was a fight going on somewhere close at hand, and equally plain was it that travellers were being robbed and maltreated by some forest ruffians, of whom there were always a number in all the royal forests, where fat bucks might chance to be shot, undetected by the king's huntsmen.

The lads had both cut themselves stout staffs to beat down the obstructions in the path. Now they grasped their cudgels tightly in their hands and looked at each other.

"Let us to the rescue!" quoth Jack, between his clenched teeth. "I can never hear the sound of blows without longing to be in the thick of the fray. Like enough in the gathering shades the assailants will think we be a larger party, and will make off. Be that as it may, let us lend our aid whilst it may serve those in distress."

Leofric nodded, grasping his staff firmly in his hand. He had all the courage of a highly-strung nature, even if he lacked Jack's physical vigour.

Springing through the leafy glades of the forest, they soon came upon the scene of the encounter, and easy was it to see that robbery and spoliation was the object of the attack.

Four stalwart young men, wild and dishevelled of aspect, armed with stout cudgels and bows and arrows, had set upon two travellers, whose clothes denoted them to be men of substance. They had been overpowered by their assailants, though plainly not till a severe struggle had taken place. Both were now lying upon the ground, overmastered each by a pair of strong knaves; and in spite of their cries and struggles, it was plain that these sturdy robbers were rifling them of such valuables as they possessed.

Jack took in the situation at a glance. With a yell of defiance he sprang upon the nearest rogue, and hurled him backwards with such right good will that he reeled heavily against a tree trunk, and fell prostrate, half stunned. In a second the traveller had wrenched himself free from the other assailant, and had dealt him such a sounding blow across the pate (he having laid aside his stick in order the better to plunder) that he measured his length upon the turf, and lay motionless; whilst the other pair of bandits, who had been belaboured by Leofric, seeing that they were now overpowered and in no small danger of capture, flung down their booty and made off to the woods, dragging their helpless comrade with them.

It was no part of the travellers' plan to take into custody these knaves, and they made no attempt to detain them, glad enough to see them make off in the darkening forest. But they turned to their preservers with words of warm gratitude, and showed how narrowly they had escaped being muleted of rather large sums of money; for one had a belt into which many broad gold pieces had been sewn, and the purse of the other was heavy and well plenished.

"We are travelling to Oxford," said he of the belt. "We joined for a time the convoy of one of the 'fetchers,' conveying young lads and poor clerks thither. But as we neared the place we grew impatient at the thought of another night's halt, and thought we would strike across the forest ourselves, and reach our goal soon after sundown. But we missed our way, and these fellows set upon us. It is a trade with some lewd fellows calling themselves clerks, and often pleading benefit of clergy if caught, to infest these woods, and fall upon scholars returning to the University, and rob them of such moneys as they bear upon their persons."

Leofric's eyes were wide with amaze.

"Surely those fellows were not clerks from Oxford?"

"Like enow they were. There be a strange medley of folks calling themselves by that name that frequent the streets and lanes of the city, or congregate without the walls in hovels and booths. Some of these, having neither means to live nor such characters as render them fit subjects to be helped from any of the chests, take to the woods for a livelihood, shooting the King's bucks or falling unawares upon travellers. Some clerks run to the woods for refuge after some wild outbreak of lawlessness. There be many wild, lawless knaves habited in the gown of the clerk and wearing the tonsure. Are ye twain from Oxford yourselves, or bound thither, since ye seem little acquaint with the ways of the place?"

Explanations were quickly made, and the two elder youths, who might have been eighteen and nineteen years old perhaps, suggested that they should finish the journey together on foot, lading themselves with the contents of the canoe, but leaving it behind in the alders, to be fetched away some other time if wanted. They were near to the river by this time, and the lads quickly fetched their goods, glad enough to travel into the city in company with two comrades who plainly knew the place and the life right well.

They were very open about themselves. The name of one was Hugh le Barbier, and he was the son of an esquire who held a post in the house of one of the retainers of the Earl of Leicester—"the great De Montfort," as the youth proudly dubbed him. His companion was Gilbert Barbeck, son of a rich merchant. His home was in the south of England, but he had been travelling with Hugh, during an interlude in their studies. In those days regular vacations were unknown. Men might stay for years at the University, hearing lectures all the time through; or they might betake themselves elsewhere, and return again and resume their studies, without reproof. The collegiate system was as yet unknown, though its infancy dates from a period only a little later. But there was a Chancellor of the University (if such it could be called), and learned men from all lands had congregated there; lectures in Arts and also in the sciences were regularly given, and degrees could be taken by those who could satisfy the authorities that they had been through the appointed courses of lectures, and were competent in their turn to teach.

The religious houses had been the pioneers in this movement, but now there was a reaction in favour of more secular teaching. The monks had some ado to hold their own, and obtain as many privileges as were accorded to others; and friction was constantly arising.

Moreover the recent migration of friars to Oxford had struck another blow at the older monastic system. The personal sanctity of many of these men, their self-denying life, their powers of preaching, the strictness with which they kept their vows, all served to produce a deep impression upon the minds of those who had grown weary of the arrogance of the Priors and Abbots.

The Grey Friars in particular, followers of St. Francis, were universally beloved and esteemed. They went about barefoot; they would scarce receive alms in money; their buildings were of the poorest and roughest, and were situated in the lowest parts of the town. They busied themselves amongst the sick and destitute; they lived lives of self-denial and toil. The favour of princes had not corrupted them, and the highest powers of the land spoke well of them.

Hugh told all this to his comrades as they walked through the darkening forest. He was plainly a youth of good parts and gentle blood, and he seemed taken by Leofric's refined appearance and thoughtful face.

"I would not go to Osney, or live in the Domus Dei there," he said. "Thou hast saved me the loss of all my wealth; it would go hard if thou wouldst not accept the loan of a few gold pieces, enough to establish thyself in some modest lodging in the town, or even in one of the empty niches upon the walls, where clerks have made shift to dwell ere now. Out beyond the walls, shut up on the island of Osney, away from all the bustle and roistering and tumult of the town, it scarce seems life at all; and methinks the monks will get hold of thee, and win thee to be one of themselves. Better, far better, be one of us in the town. Then wilt thou see all that is to be seen, and learn far more, too, than thou wilt in the schools of the monks."

Leofric listened eagerly to this advice.

"Is Osney then without the walls?"

"Ay verily, on one of the many islands that the river makes in its windings. Oxford itself is little more than an island, for that matter, since the city ditch has been dug on the north side of it. But within the city there is life and stir and stress, and all the Halls where the students lodge are there, and the lodgings amongst the townsfolks which some prefer. Come and belong to us, not to the monks. So wilt thou learn the more, and enjoy life as thou couldst not do cooped up on yon damp island in the Domus Dei?"

"I would fain do so," answered Leofric readily. "I have no desire for a monkish life. I would see what life is like without the cloister wall. But I have little money; I love not debts—"

"Tush! be not over scrupulous. Thou hast done me one good turn; I claim right to do thee another. Now no more of that. Let us put our best foot forward; for it will be dark ere we reach our destination. Perchance we may yet have to camp once more in the woods; for if the city gates be locked, we may have some trouble in getting admitted. The townsmen, albeit they live and thrive by them, love not the clerks. They will do us a bad turn an they can; yet methinks we are even with them, take one thing with another!"

Hugh showed his teeth in a flashing smile, and Gilbert laughed aloud. Then the party strode on through the darkness, till they paused by common consent to light a fire and camp for the night in company—it being plain by this time that they could not enter Oxford that night.

CHAPTER III.

OLD OXFORD.

With glowing cheeks and beating hearts, Leofric Wyvill and Jack Dugdale beheld the walls of Oxford towering above them in the clear morning sunlight.

For many long hours during the previous night had the four travellers sat over their camp fire, listening and telling of the life of the mediaeval University city. Already Leofric and Jack felt a thrill of pride in the thought that they were to be numbered amongst its sons; already they had wellnigh made up their minds that they would set up together in some nook or turret in the city walls, make a sort of eyry there for themselves, and live frugally upon the small sum of money they possessed, until they were able to earn something towards their own maintenance, or could borrow from one of the "chests" provided for the benefit of poor students.

Hugh had carried his point, and Leofric's purse now held a few gold pieces as well as his own small store of silver. By the exercise of economy the two friends would be able to live in modest comfort for a considerable time, and Leofric, at least, hoped before long to earn money by his penmanship and talent in illuminating parchments.

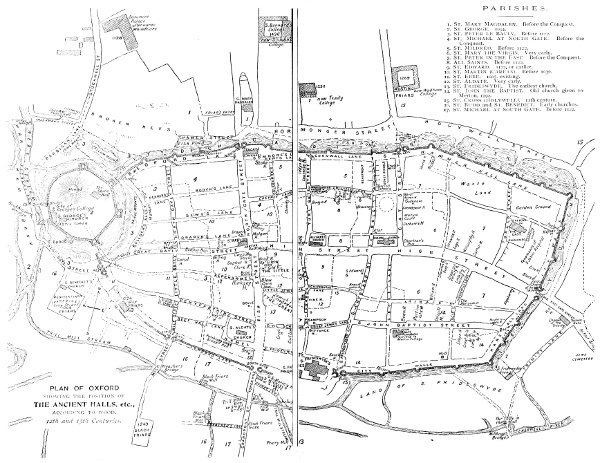

PLAN OF OXFORD

SHOWING THE POSITION OF THE ANCIENT HALLS, etc.,

ACCORDING TO WOOD.

12th and 13th Centuries.

They knew by this time where their new comrades lived. Gilbert had a lodging with an honest citizen of the name of Seaton, who kept a shop hard by Carfax, and sold provisions of all sorts to clerks and others. He was one of the burgher class, who contrived to keep on good terms both with the scholars and his fellow-citizens, and in the frequent collisions between "town and gown"—to borrow the modern phrase—he stood good-humouredly aloof, and would not take sides in any dispute.

Hugh lived in one of the many Halls which had sprung up within the city walls. These were not collegiate institutions, but were merely places of abode, hired perhaps by a number of clerks collectively, perhaps by some master, who received inmates as boarders. They lived in these houses, and took their meals there—everything being of the roughest and simplest description—and attended lectures in the different schools according to their own fancy. Some of the richer students enlisted the services of a tutor; but many lived a free and lawless existence, learning almost nothing, frequenting lecture just for the fashion of the thing, but making no progress in scholarship, and spending the best part of the day in amusement or fighting.

In the schools attached to the religious houses there was more order, more comfort, and more decency of life than in these self-constituted Halls; but amongst such clerks as had no leaning towards the religious life there was a strong feeling of preference for simply secular abodes; and there were difficulties between the monks and the University authorities with reference to the course in Arts which held back many from attaching themselves to the monastic schools.

All this Leofric and Jack had been told with more or less of detail, and already Leofric was resolved against settling himself upon Osney Island, in the Domus Dei there. He would present his letter to the Abbot, but not until he had made a nook for himself somewhere else. Gilbert declared that he knew of a little turret in the city wall, not far from Smith Gate, in which two students had lived for a considerable time. If it were empty, they could take possession of it, and by the expenditure of a little money and ingenuity could transform it into quite a respectable living-chamber for themselves. Many a poor clerk had inhabited a chamber of that sort before, and Jack and Leofric secretly thought that they should prefer the quiet life on the wall to the noise and confusion which plainly too often reigned in the various Halls.

"We will go in by Smith Gate, and see if the turret be empty," said Gilbert; "if so, these lads can take possession forthwith, and we will show them where they can provide themselves with such things as be needful for them."

They were nearing the city by now. Already there had spread beyond the walls a certain number of Halls and other buildings. The Church of St. Mary Magdalene and the colony of the Austin Friars were without the wall on the northern side, and a few Halls had sprung up along Horsemonger Street, as it was then called, which was on the north side of the city ditch, where Broad Street now runs.

The Austin Friars were only just beginning to appear in Oxford; but the Black, White, and Grey Friars had already obtained a footing in the city. As the travellers approached the gate, they saw the cowled figures flitting about, some with black habits over their long white under-dress, some with a simple gown of grey or brown, bound with a cord at the waist. These latter, who all (save the old and infirm) went barefoot, were the Franciscans or Minorites—the Grey Friars of whom the lads had heard; and they regarded them with curiosity and veneration, believing them to be full of sanctity and virtue.

Out through the gate, just as the youths approached it, came a couple of Masters in their gowns and hoods. Leofric and Jack scanned them curiously, and eagerly inquired of their companions who they were.

"Nay, I know not the names of all the Masters in the city," answered Hugh, laughing; "there be too many for that. Belike they have been lecturing in School Street this forenoon, and are going back to their Halls. Some of these same Masters will like enough come and invite you twain to attend their lectures; but give not too ready an answer to the first who asks. Rather visit several and pick out those who please you most. It is oft the poorest and least learned who are most eager for listeners, the better sort having always their lecture-rooms full."

And now they were actually within the city precincts. Smith Gate being so close to School Street, the eager eyes of the two new-comers were immediately gratified by the sight of many hurrying figures of clerks and Bachelors and Masters, some going this way and some the other, talking earnestly together, disputing with some warmth and eloquence, or singing snatches of songs, like boys released from school.

It was not easy for unaccustomed eyes to distinguish the rank of the various passers-by; for academic dress was still in its infancy, and there were few, if any, statutory rules respecting it. The habit of the clerk was very much what he wore at home, and the black cappa of Bachelor or Master was often the same, though Masters were beginning to wear the square, tufted cap, and had the right to the miniver hood of the nobles and beneficed ecclesiastics. The scarlet gown of the Doctor had just come into use, but was at present seldom seen, as many were unable to purchase so costly a robe. The most common garment for every person in the University was the "tabard" with the girdle, and these tabards might be either red, black, or green; but black was the commonest colour, as being the most serviceable in daily wear.

Fain would the lads have lingered to watch the shifting throng of clerks and their preceptors, as they streamed out from the lecture-rooms for the mid-day meal; but Hugh and Gilbert laughed at their eager curiosity, and drew them along to the left down Hammer Hall Lane, pausing suddenly upon reaching a small turret in the wall, which once had been open to the street, but was now closed in by a few mouldering boards.

"Good!" cried Gilbert, as he pulled aside one of the boards; "the place has not been taken. Now look well at it, you two, and see if you think you can make shift to live here till a better place offers."

Pushing their way within the circular recess, the lads saw that a rude stairway led up to some sort of chamber overhead. Mounting the rickety steps with care—for they had become loose and rotten—they found themselves in a small and not unpleasing little chamber, lighted by several long, narrow loopholes, and roofed in securely from the weather overhead.

The flooring was rather decayed, and there was a mouldering smell pervading the place; but its former occupants had done various things to render habitation possible. A fireplace and chimney had been contrived in one corner, and some rude shutters had been affixed to keep out the cold air at night, or in inclement weather. A rickety shelf that would serve as a table still hung drooping from its nail. Plainly the place had been lived in before, and might well be again. Leofric and Jack looked round it, and smiled at one another.

"We could live here like princes, if there be nothing to hinder," said the latter. "Can we come and fix our abode here without making payment to any one?"

"Marry yes, since nobody uses the place. There be many such nooks along the walls, and poor clerks have settled themselves there again and again, no man saying them nay. In times of war they might post archers or marksmen at these loopholes; but short of a siege, I trow none will disturb you. And from without ye can climb easily upon the wall, and enjoy the air and watch what goes on beneath. Also there be the Fish Ponds just below, and I warrant ye will catch many a good supper from thence when ye be in need of a good meal."

Jack laughed, for he had no small skill as a fisherman; but just now he was all agog to see Oxford and settle into these new quarters.

"Had I but a few tools and some boards, I would fix us up bench and table, mend the stairs and the floor, and make the place as comfortable as heart could wish," he cried.

"And I would gather rushes for the floor, and wood for the fire, and we should feast right royally on the last of the provisions we laid up for the way," added Leofric.

"Then come away to Carfax, where ye can lay in such stores as ye need," cried Gilbert. "I will take you to honest Master Seaton, where I have always lodged. He will tell you where to go for all ye need, and the right price to pay: for there be dealers in the city who seek to mulct clerks and scholars, and charge them more than the fair price for goods; and the Chancellor, and even his Majesty the King, have had to interpose."

"What is Carfax?" asked Leofric, as, after depositing their goods carefully in the turret, they replaced the boards and sallied forth once more.

"Why, the meeting of the four great streets of the town—Quatrevois some folks call it—where High Street, Great Bayly Street, Fish Street, and North Gate Street all meet. St. Martin's Church is there with its great bell, and whenever there be strife 'twixt citizens and clerks, that bell booms out to gather the citizens together; whilst our rallying-point is St. Mary's, whose bell rings to warn us that they are rising against us. At other times Carfax is the chief mart of the city, and the bull-ring stands in the centre. But come, and thou shalt see for thyself; and good Master Seaton will give us all some dinner, I trow."

Gilbert led the way, and the rest followed him willingly. The streets had thinned considerably, the noontide hour having driven in clerks and masters alike to their dinner. Gilbert strode down Cat Street, and pointed out to his comrades several Halls situated there, and sounds of laughter and loud talking and jesting broke upon the ears of the passers-by, plainly indicating the proximity of considerable numbers of inhabitants.

"That was the Hall where I lived last," observed Hugh, as he pointed to a house, somewhat better than the rest, on the left-hand side as they walked down Cat Street. "Corbett's Hall it was then called; and the Master was an excellent man. I heard he was about to go elsewhere; probably I shall find a new head by now. But I will not pause there now; I will wait till the fetcher has brought in my goods and chattels. I will come with you to Carfax, and pay my respects to good Master Seaton first."

So on went the four, the pair who had never before seen a town gazing with wonder at the quaint-timbered houses on either side the street, whose projecting upper floors seemed almost to meet overhead. There was no footpath or paving of any sort; the roadway was but a track, deep in mud in winter, and in dust in summer. St. Mark's Church at the corner, where they turned into High Street, brought Leofric to a standstill, for such edifices were new to him; but his companions laughed and hurried him on, telling him he could drink his fill of churches in Oxford any day he chose, but that Master Seaton's dinner would not wait for his leisure.

On they went along this wider thoroughfare, not pausing to examine anything in detail, but taking in the general effect of a populated city, which was immensely wonderful to the two lads from the country, till Gilbert pointed to a tall tower standing out against the sunny sky, and said,—

"Yon is St. Martin's Church, and this is Carfax."

It was, as he had said before, just a meeting of the ways, but such a sight as it presented Leofric and Jack had never dreamed of. The open place seemed full of people: there were stalls on which merchandise of all sorts was being vended; loud-voiced salesmen were crying their wares, or chaffering over bargains with customers. There were shops, with signs swinging over them, that displayed a better sort of ware; and lads of all ages, from thirteen upwards, in the tabard of clerks, were strolling about, buying or examining goods, or exchanging a rough sort of banter with the townsmen. A few Masters or Bachelors would be seen threading their way through the crowd, but they did not often linger to speak to any; it was the clerks who seemed to have all the leisure, and some of these were playing games or throwing dice, whilst others looked on, encouraging or jibing the players.

"Heed not that rabble rout," said Gilbert, forcing his way towards a rather fine-timbered house at the corner, where Fish and High Streets joined; "come to Master Seaton's house, and let us hear all the news."

Gilbert led the way into a shop, where he was greeted somewhat boisterously by a merry-looking youth behind the counter. He nodded a reply, and pushed open a door which gave access to a steep and narrow staircase, and after ascending this he opened another door, and instantly a number of voices were raised in welcome and greeting.

Gilbert and Hugh pushed into the room from whence these sounds issued, whilst Leofric and Jack stood together just on the threshold, gazing about them with curious eyes.

They saw before them a quaint, pleasant room, rush-strewn, and plainly furnished with table and benches, in which a party of six was gathered, seated round the board, which was hospitably spread with solid viands.

The master of the house was easily distinguished by his air of authority and his general appearance. His wife was a comely dame, ruddy of face and kindly of aspect. On either side of her sat a pretty maiden, one of sixteen, another of fourteen summers; and the good-looking, strapping youth, who was now greeting Gilbert and Hugh right eagerly, was very plainly the son of the house. An apprentice looked on wide-eyed and silent at the apparition of four strangers; yet it was plain that neither Gilbert nor Hugh were so regarded in the Seaton household.

Not only were they joyfully received themselves, but their two comrades quickly shared in the hospitable welcome. They were placed at the table, their trenchers were heaped with good food, and the story of the encounter in the forest was eagerly listened to by all.

"There be many poor rogues who have taken to the forest in these times of scarcity," said Hal Seaton, the son. "The harvests have been bad, and prices have been raised; and the idle and prodigal have had much ado to keep body and soul together. Sometimes they take to theft and pillage, and then flee to the forest for safety; and some go thither in the hope of killing a fine buck unseen by the huntsmen, or to rob unwary travellers, especially those that be coming with full purses to pursue their studies here."

"Ay, and there be some that think there will be fighting ere long 'twixt his Majesty the King and the Barons," added Seaton himself gravely. "Heaven send such a thing come not to pass! It is ill work when brother takes up arms against brother, and city against city."

The youths would willingly have asked more of the state of parties at this stirring season, but just now personal matters were of more pressing importance. So they left politics for another time, and told about the turret hard by Smith Gate, where Leofric and Jack were about to ensconce themselves; and Hal begged a half-holiday from his duties in the shop, that he might take his tools, and some odds and ends of planks lying about in the workshop behind, and help the lads to settle themselves in.

This was willingly accorded, and Master Seaton and his wife both showed great kindness to the would-be clerks. The former unearthed from his stores some strong sacking fashioned into huge bags, that, stuffed with straw or dead leaves, did excellently for bedding; and the latter put up in a basket a liberal supply of food from her well-stocked larder, for her motherly heart went out towards the two lonely lads, coming to settle in a strange city, knowing nothing of the life before them. Leofric's blue eyes and gentle manners won her affections from the first, and no one could help liking honest Jack, who was so merry and so full of hope and courage.

Laden with a number of useful odds and ends, the little party made their way back to the turret chamber; and soon the sound of hammer, chisel, and saw spoke of rapid advance in the necessary work.

Leofric crossed the river again to gather dead leaves and bracken for bedding, wood for firing, and rushes for the floor. By the time he had collected and brought in sufficient stores, the work overhead had rapidly progressed, and he uttered an exclamation of delighted astonishment as he beheld the result of the afternoons toil.

The stairs and flooring were mended, rudely, to be sure, but strongly. Something like a fastening had been contrived to the lower entrance, so that they could use the basement of the turret as a storehouse for wood and other odds and ends. Up above, the little chamber began to look quite comfortable. The holes in the masonry had been filled up with mortar or patched by boards. The window shutters had been mended, and could now be used for keeping out inclement wind. One of the loopholes had actually been glazed by Hal's deft fingers, and he promised to keep his eyes open for any chance of picking up some more glass, so that the others might be served in the same way. To be sure, the glass of those days was none too translucent, and save in very cold weather, it was pleasanter to have the loopholes open to the light of day; but if heavy rain or bitter cold should drive the occupants to close their shutters, it was certainly advantageous if one or two of the narrow slits could be glazed, so that they would not be left in total darkness.

The shelf table against the wall had been mended, and two stools of a suitable height contrived. When the fire was lighted on the hearth, and the smoke had been coaxed to make its way up the chimney, the place wore a really cosy and home-like aspect, which was greatly enhanced after the floor was strewn with rushes, and the two mattresses stuffed and laid side by side in a little recess. The spare habits of the boys were hung against the wall on pegs, and their few worldly possessions laid in order upon the shelf which had been fixed up to receive them.

"I vow," cried Hugh, as he looked around him, "that I would almost sooner have such a lodging as this than spend my days in a Hall. There be Halls where fires are scarce known save in the coldest weather, and where the rushes lie on the floor till they rot, and become charged with so much filth that the stench drives the luckless clerks out into the streets. It hath not been so where I have lodged, 'tis true; but there be Halls wherein I would not set foot for the noisome state they are in."

Leofric and Jack were charmed with their quarters, and when their guests had bid them good-bye, and they had fastened themselves in for the night, they looked at each other with a sense of triumph and joy. Here they were, established as a pair of clerks in a lodging of their own in Oxford, where none was likely to molest them. They had money in their purses enough to last them a considerable time. They had made kind friends who would help them through the difficulties and perplexities of their first days; and surely before long they would find themselves at home in this strange city, and would enter into its busy life (of which they had caught glimpses to-day) with the zeal and energy of true students.

As they sat at their table, partaking with good appetite, though frugally, of the provisions left from the journey, seasoned by some of Mistress Seaton's dainties, they spoke together of their plans for the morrow.

"Methinks I should go to Osney, and present my letter. But I shall have no need to ask for shelter in the Domus Dei, seeing how well we be sheltered here."

"And I would fain see something of the good Grey Friars, of whom so much good is spoken in the town," answered Jack; "and we must seek out such Masters as we would learn from, and find out what fee we must pay to attend their lectures. It is not much, methinks, that each clerk gives, but we must be careful how we part with our money, for we may not find it easy to put silver in our purse when our store has melted away."

"I shall ask the Abbot of Osney if he will give me vellum or parchment to illuminate, for I have some skill that way," said Leofric; "I used to help the monks of St. Michael. I might e'en do the same here; and, perchance, I might teach thee too, good Jack."

Jack looked at his rough, red hands, and shook his head.

"I can make shift to read and write, but I never could do such work as that," he answered. "I will fish in the ponds, and snare rabbits in the woods, and make bread of mystelton for us to eat. My care shall be the larder, and thou shalt have leisure for work if thou canst get it. So will we live right royally in our nook, and learn all that Oxford can teach us!"

CHAPTER IV.

THE FIRST DAY.

The lads slept soundly in their new quarters, but awoke with the first light of day, eager to enter upon the strange life of the city. Making their way first to the top of the wall, they had a good look round them over the still sleeping town; and then finding a place where, by the exercise of a little activity, they could clamber down on the outer side, they refreshed themselves by a plunge in the Fish Ponds, by way of ablutions, and returned through the gate to their lodging.

They had a great curiosity to go forth together and see the city, but they did not intend immediately to decide upon the preceptor they should follow. Just at starting they felt almost too excited to settle to regular study, and the visit to the Abbot of Osney was the first business of the day.

Putting on their better habits, and making themselves as trim and neat as circumstances permitted, the boys sallied forth, and took the way to Carfax as before. They knew that Osney lay to the west of the city wall, beyond the Castle, and they had a great wish to see that building at close quarters; so they pursued their way along Great Bayly Street, till they reached the mound itself, crowned with its frowning walls and battlements.

As they passed along they saw not only numbers of clerks sallying forth to their daily lectures, but great numbers of the Black Friars, who appeared to be exercising considerable activity. Some were wheeling little trucks or carts which held loads of what appeared to be goods and chattels, and they appeared to be very busy, passing to and fro with their loads or their empty trucks, like a colony of industrious ants.

"What are they doing?" asked Jack of a bystander.

"Removing themselves from the Jewry to the new House that the King's Majesty has bestowed upon them without the city walls through Little Gate and down Milk Street," was the answer. "They came and settled in the Jews' quarter, hoping to convert the Hebrew dogs to the true faith; but methinks they have but a sorry record of converts. Anyhow they are going thence, and their new house is all but ready. A few may linger on in the Jewry, but the most part will fare forth to the more commodious building yonder."

Having thus satisfied their curiosity on that score, the boys passed onwards to the Castle, and just as they approached the West Gate, they were in time to prevent something of a catastrophe. As they drew near, they perceived that a young lady, mounted on a fair palfrey, was approaching from the outer side. She was quite young, perhaps fifteen or sixteen, and was very fair to look upon. Her hair was a dusky chestnut colour, and was loosened by the exercise of riding, so that it framed her face like a soft cloud. Her eyes were bright and soft and dark, and her figure was as light and graceful as that of a sylph. As the two lads passed under the gateway, marking her approach, they bared their heads, and glanced at her with honest admiration in their eyes.

The little lady noticed their salutation, and returned it with a gentle dignity of manner; but just at that moment a piece of rag lying in the gutter was suddenly whirled round and up by a gust of wind, right against the face of the spirited little barb she was riding.

The creature suddenly took fright, reared up on its hind legs, and then made a sudden swerve, dashing off along West Gate Street at a headlong pace.

But luckily the girl rider was not borne away too in this reckless fashion. When the creature started and reared so violently, she had been almost unseated; and Leofric, seeing this, had with one quick movement thrown his arm about her; and as soon as the palfrey swerved and made off, the lady was simply lifted from her seat and gently set down by the strong arms of both lads—for Jack had rushed up to give assistance.

She stood now in the roadway, dazed, but safe, looking from one of her preservers to the other, and faltering out broken words of thanks.

Then the servant who had been behind, and who had in vain striven to stop the runaway horse, rode up, lifted the little lady to his saddle, and carried her away, before she had sufficiently recovered her breath to do more than wave her hand to her two deliverers.

The sentry at the gate, who had now come up, looked after them with a laugh.

"Old Ralph is a grim guardian. He will never let his young mistress have speech of any. But I doubt not when it comes to the ears of the Constable, he will seek you out to reward you; for fair Mistress Alys is as the apple of his eye."

"Who was the lady?" asked Jack eagerly.

"Mistress Alys de Kynaston, only daughter of the Constable of the Castle, Sir Humphrey de Kynaston. They say she is the very light of the house, and I can well believe it."

After a little more talk about the Castle and its Custodian, the sentry directed the lads how to find Osney Abbey; and after crossing Bookbinders' Bridge and passing the Almshouses, they quickly approached the gate by which access was had to the Abbey itself.

It was a fine building, inhabited by the Canons Regular of St. Augustine. There were the Chapel, dedicated to St. Nicholas, the fine cloistered refectory, the Dormitory, the Abbot's Lodging, to say nothing of the fine kitchens, and the Domus Dei of which mention has been made.

The present Abbot was Richard de Appelton, and when Leofric presented his letter and asked speech of him, he was ushered into the presence of the great man with very little delay.

Strangers, even youthful strangers, were always received hospitably at the religious houses, and the Abbot, after reading the letter of his friend, spoke kindly to the boys, asking them whether they desired the shelter of the Domus Dei.

Leofric explained what had befallen him since that letter was penned, and how he had met with kind friends, and had already found a lodging within the walls of the town. The Abbot stroked his shaven chin, and looked from Jack to Leofric, letting his eyes rest somewhat longer upon the face of the latter as he said,——

"So thou art not as yet disposed to the religious life? Yet thou hast the face of a godly youth."

"I trust we may yet be godly without the cloister wall," answered Leofric modestly. "It is not for roistering and revelry that we have chosen to live within the town, but we would fain have some small spot that we may call our own, and I had thought that perchance I might turn such skill as I have in penmanship to account, so that I might earn fees for——"

"Ah yes, I know what thou wouldst say. Perchance we can give thee some work of that kind from time to time. But there be other ways of winning money too, open to poor clerks. Thou canst say a prayer or a grace at some rich man's table, or the Chancellor will give thee a licence to beg for thy maintenance. A likely youth, with a face like thine, will not find living hard. And if thou art ever in any trouble, thou canst always come to me. The Domus Dei is open to such as thou, and any son who comes from my good friend the Prior of St. Michael will be welcome for his sake."

Leofric thanked the Abbot gratefully, and received from him a small present in money, and two or three squares of vellum, such as were used in the making of breviaries. This was a very great acquisition for Leofric, as he could now begin some illuminating or transcribing work in his leisure hours, and by the sale of this add to their scanty store of money, and obtain the material for fresh work of a like kind.

This he preferred greatly to begging, notwithstanding that mendicancy had been made respectable, if not honourable, by the friars, and that to give alms to a poor clerk, or reward him for singing a "Salve Regina," or saying a prayer or grace, was one of the regular and esteemed forms of charity.

"And remember, good lads, that there are homes in the city open to such as ye," said the Abbot, as he bid them adieu. "There is Glasson Hall in the High Street, which pious John Pilet gave to Osney Abbey not long since. We might find room for the pair of you there, if you were disturbed in your nest. There is Spalding Court in Cat Street, which the burgesses of the town have bought for the use of poor clerks; and there be Halls where the poorer clerks serve the wealthier, and earn a pittance thus. Ye will find many ways of living; and pray Heaven we have a good harvest this year, so that the present scarcity may cease."

And with a nod and a word of blessing the Abbot dismissed his young guests.

"Let us take a prowl round the town," said Jack, as they turned their backs upon the stately buildings of the Abbey, "there is so much to see at every turn, and I would fain know the streets and lanes of the city by heart. We must enter by the West Gate that we left, but we will wander round the walls and see what lies in the south ward of the city."

Leofric willingly agreed, and they retraced their steps as far as the gate, where they were at once hailed by the same sentry as had spoken to them before.

"Fortune favours you, honest lads," he said. "The Constable of the Castle has just sent down this purse, to be given to the two clerks who saved the Mistress Alys from hurt when her palfrey took fright," and he put into the hands of Jack a small leathern satchel, in which were a goodly number of silver pieces.

"Now this is luck indeed!" cried the youth, as they took their way onward. "We meet with success at every turn. Methinks that either thou or I must have been born beneath a lucky star."