True Stories of Girl Heroines

Evelyn Everett-Green

TRUE STORIES OF GIRL HEROINES

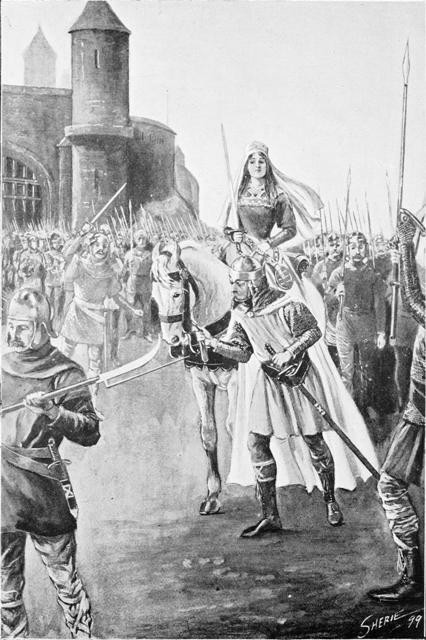

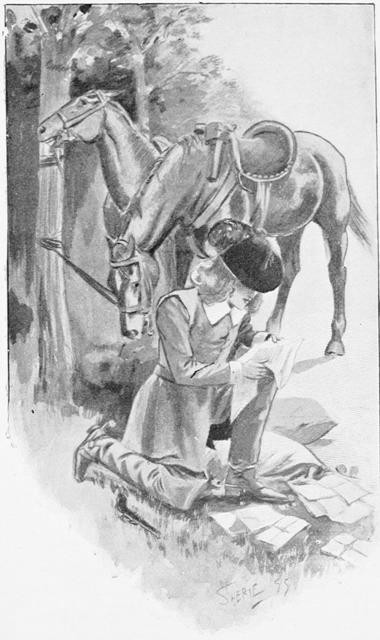

The brave young wife rode forth at the head of her whole garrison.

The brave young wife rode forth at the head of her whole garrison.

Page 109. Frontispiece.

TRUE STORIES OF GIRL HEROINES

BY

E. EVERETT-GREEN

AUTHOR OF "GOLDEN GWENDOLYN," "THE SILVER AXE," "OLIVIA'S EXPERIMENT," ETC.

WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS BY

E. F. SHERIE

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & CO.

LONDON

HUTCHINSON & CO.

CONTENTS

PAGE

INEZ ARROYA 1

CATHARINE THE ROSE 17

ELSJE VAN HOUWENING 35

GRIZEL COCHRANE 55

EVA VON GROSS 73

EMMA FITZ-OSBORN 93

ELIZABETH STUART 111

CHARLOTTE HONEYMAN 131

MARY BRIDGES 149

THERESA DUROC 167

JANE LANE 185

HELEN KOTTENNER 205

MAID LILLYARD 223

MARGARET WILSON 241

AGOSTINA OF ZARAGOZA 259

AGNES BEAUMONT 277

HANNAH HEWLING 297

MONA DRUMMOND 317

JESSY VARCOE 337

URSULA PENDRILL 355

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The brave young wife rode forth at the head of her whole garrison Frontispiece

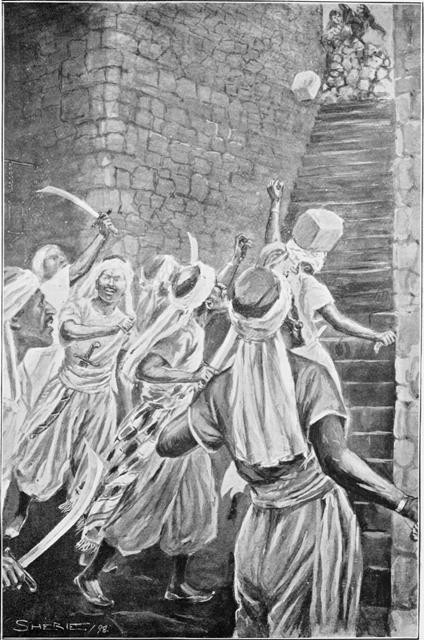

The first great stone leapt from her hand and went bounding and crashing upon the head of the foremost Moor To face p. 8

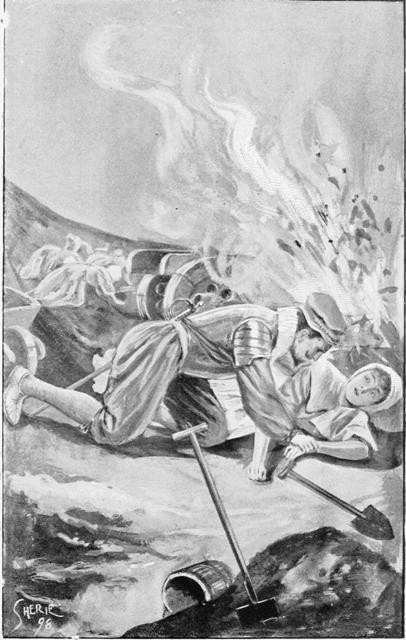

The Commandant pulled her down beside him before it was too late " " 30

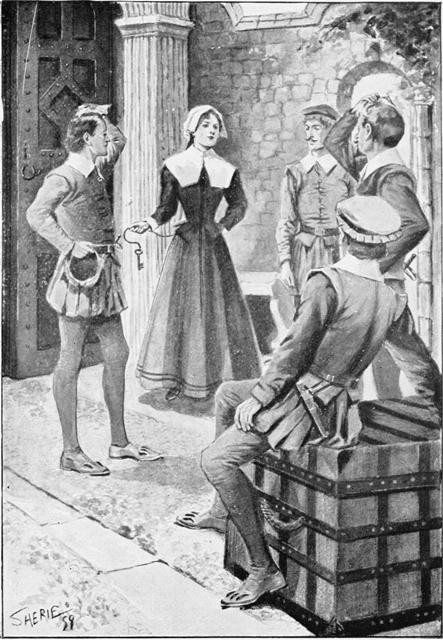

"Is the chest to be examined before it goes on board?" " " 48

With a beating heart Grizel tore open this bundle and looked at its contents " " 66

He stopped short on seeing the Countess " " 125

Suddenly, close above her, the steps came to a dead stop " " 145

Theresa forgot everything in the sight of the child's peril. " " 183

"Well, now, I did hear as young Charles Stuart himself was taken," answered the smith " " 193

The men plunged down into the vault " " 218

She set herself in their ranks, and went charging down the hill " " 237

A wounded man half rose from the ground at their feet " " 270

Bunyan looked down at her with rather a grim smile upon his face " " 283

The Judge plucked his robe out of her detaining hand. " " 310

"Dare to come one step nearer, and I fire" " " 335

"The first man that touches him I'll kill!" cried Jessy " " 351

True Stories of Girl Heroines

INEZ ARROYA

"Mistress! my mistress! the Moriscos are upon us!"

Inez sprang to her feet, the rich southern blood receding for a moment from her cheek, as those words fell upon her ears—words of such fearful significance to the Christian inhabitants of the Moorish territory along the Sierra Nevada.

"Juana, what mean you? Speak, girl! What have you heard? What have you seen?"

Juana's face had been white when she came bursting in upon her young mistress; she held her hand to her side; her breath came and went in great gasps; yet already she was recovering the power of speech, and she seized Inez by the arm.

"Mistress, they are below already; they are robbing the house. Can you not hear them? When they have taken the wine and the oil they will come hither and murder us!"

Inez held her breath to listen. Yes, there were sounds from below—sounds of voices—loud, threatening voices, and the laughter of men assured of victory.

Juana, the maid, spoke in a fierce whisper. Fear was receding. The high courage which comes to weak women in the hour of extremest need possessed the hearts alike of mistress and maid.

"The master went forth not an hour ago. Five minutes since little Aluch ran up to tell me that, as the master was taking the air, there suddenly appeared a band of rebel Moriscos from Orgiba, who set upon him, and chased him, and would have killed him, but he took refuge in his father's house; and he will hide him, and get him safe away. But all Istan will join the rebels, and already they are crying that every Christian shall be slain!"

"Every Christian!" cried Inez, with a flash in her dark eyes. "And how many Christians are there in Istan? Two weak women, Juana, you and I, and my uncle, whom they have already set upon and chased to the mountains. Pray Heaven and our Lady that he may reach them safely, and send us help from Marbella, else there will be but short work with the Christian population of Istan."

There was scorn in the girl's voice, scorn in the flashing eyes. Istan was a Moorish village, where one Christian priest had been placed to work amongst the Moslems, and seek to convert them to the true faith.

Success in this missionary work had been small; but the good man had hitherto lived in peace with his alien flock. The wise and kindly traditions of Ferdinand and Isabella, and Hermando de Talavera, had for long kept under the natural hatred of Moor towards Christian in Southern Spain. But a monarch had arisen who hated the word toleration. To keep faith with the Moslem was to break it with the Almighty. The edict of 1567 was now a year or more old, and its pernicious effects were already made abundantly evident in fierce Moorish risings here, there, and everywhere.

Inez had heard stories as to the fate of Christian prisoners who had fallen into the hands of the Moors. Before she followed Juana she had caught up a shining dagger which hung against the wall; and she thrust it into her girdle as she ran down the broken steps of the tower.

"At least, they shall not take us alive!" she breathed to herself; and Juana seemed to hear, for she flashed back a glance at her young mistress, and for a moment showed the gleam of a long stiletto which she carried in the bosom of her tunic.

The priest of Istan dwelt in a strange house. It was, properly speaking, no house at all, but a Moorish fortalice, dismantled and ruinous, which he had partially repaired soon after his arrival there, and which, since the arrival of his orphan niece to live with him, he had desired to make more habitable still.

The place was, in fact, a sort of tower. The lowest floor was their storehouse for supplies of wheat, oil, and so forth; and from this level came up the sound of rough voices, as the Moors leisurely removed the spoil before proceeding upwards. There was only one door from the fortalice into the world without, and this it was impossible to reach, for the Moors were swarming in the lowest part, effectually preventing their egress. They knew perfectly that the two girls were as helplessly caught as a rat in a trap; they did not even hasten the work in which they were engaged. Inez, standing at the top of the long flight of stone steps which led downwards to the basement, heard what they were saying one to another, and into her olive cheek there crept a deep glow of red, whilst her lips set themselves, her teeth clenched, and her black eyes gleamed with a light like that of fire.

"Our Lady and the blessed saints protect us!" whispered Juana, with a furtive glance into the beautiful face of her young mistress; and Inez looked back at her without a quiver as she replied:

"The Christian's God helps those who help themselves, Juana. We are not here to wring our hands and look for a miracle to save us. We fight for our lives, and Christ and our Lady will help us. See, we are not quite defenceless, Heaven be thanked for that! Collect those stones, quickly, quietly. Keep out of sight. Do not let them observe us. Get together a number, then you shall see!"

It was as Inez had said. The repairs of the fortalice, which had been already commenced, had put the means of defence into their hands. Large quantities of great stones had been collected at first in the basement, but only the previous week had been laboriously carried up the steep, narrow stairs which led upwards to the dwelling rooms; and these large stones the two brave girls were now quietly collecting in a great heap at the top of the flight.

They were in deep shadow, and below the brown-skinned men, in their picturesque Arab dress, were far too busy examining their spoil, and making away with it, to heed the slight sounds from above. They talked together as they worked; they told of the attack they had made upon Orgiba, and of that fearful massacre of Christian men, women, and children at Uxixar. Inez held her breath to listen to the confirmation of certain vague rumours which had reached them before this, but had scarcely been believed. Peaceful Istan, with its terraced gardens overhanging the lovely gorge of the Verde, had seemed so far removed from the storm and strife; and its people were peaceable and kindly disposed, even though they were Moriscos. But these men were rebels and freebooters, with the fierce lust of blood upon them, their hands red from the butchery of innocent, helpless women and children; men who laughed aloud at tales of hideous deeds done in cold blood; men mad with hatred to the conquering race, knowing themselves doomed to final defeat, yet resolved to revenge themselves in every possible way upon those of the hated faith ere their own turn came.

Upon such a band of men did Inez look down, with the fire of courageous despair in her eyes. What could they do? what hope was there for them? two slight girls against a score of trained warriors.

The Moriscos of Istan would probably not join in the attack upon them; but they would not interfere with what their brethren of the faith might do. Help from without there would be none, unless the priest himself could find means of escape, and could get to Marbella and bring it. Inez knew that he would strain every nerve in this effort. But what chance had they of holding out for perhaps six hours or more? Could it be done? Oh, could it be done? She looked at the heap of stones. She looked at the flitting forms below in the gloom. And then she held her breath once again, listening to stories of how in other places Christians had taken refuge in towers and churches, whilst their Moorish foes piled faggots soaked in pitch, and such-like inflammable material against and around the walls, and reduced the building to one mass of flames.

If they kept the men from laying immediate hands upon them, would that fiery doom be theirs?

"Better that than to fall into their hands," said Inez, between her shut teeth; and Juana, looking at her mistress, with a world of faithful love in her eyes, exclaimed softly:

"Our Lady will surely send us help, mistress. You are too beautiful to die such a death!"

Inez put her hands upon the shoulders of the faithful girl, and said in a low voice:

"You would come with me from Granada, Juana, where you would have been safe; and there were those who warned us that we might not long be safe out here. But my duty seemed to my uncle; and you—you would not leave me. And what if I have brought you hither to your death?"

"We must all die once," answered Juana, her eyes full of love and courage; "and I would sooner die with you, mistress, than live without you. If I had stayed behind, and had heard this story of you, I should have killed myself, or died for grief and shame that I was not with you."

Then Inez put her arms about the faithful girl's neck, and kissed her thrice upon the lips.

"We will do battle for our lives, Juana; and then, if needs be, we will die together," she said.

Suddenly there was a cry from below. Some one had looked up, and had seen the two girlish figures clinging together. Perhaps the very action had been misunderstood, and instantly there was a rush towards the steep, broken, narrow steps of some dozen swarthy Moors.

Instantly the girls were at their post at the head of the flight. Inez, quiet and composed, gave the word.

"Welcome to the Moriscos!" she cried, in a clear and ringing voice, as the first great stone leapt from her hand and went bounding and crashing upon the head of the foremost Moor.

"Welcome to the Moriscos!" echoed Juana, dislodging another, which sprang from stair to stair, and then, bounding sideways, went crashing upon the bent back of a man in the basement beneath, who fell like a log from the blow, his spine fractured.

Crash, crash, crash! Down hurtled the huge stones, flinging the unprepared Moriscos from the steep stairs, where they fell in a confused mass, one upon the top of the other, pinned down by the great boulders which came rolling down upon them from above, cursing, raging, crushed and maimed, utterly taken aback by such a reception; and now only eager and anxious to get out of a place that seemed to rain nether mill-stones upon them.

The first great stone leapt from her hand and went bounding and crashing: upon the head of the foremost Moor.

The first great stone leapt from her hand and went bounding and crashing: upon the head of the foremost Moor.

Page 8.

Three of their number lay stretched dead upon the ground. A number more were badly hurt; and all were flying from the stairs, which threatened to become a veritable death-trap for all who tried to mount.

There was a rush for the outer door. The wounded were dragged away groaning by their comrades; those who were sound carried the dead. They turned and shook threatening fists at the two girls standing behind their heap of stones at the top of the stairs; they promised them that they were coming back. They breathed out threats which might well make the stoutest hearts quail. But Inez stood up tall and straight, with a great stone poised in her hand; and the strength and accuracy with which those formidable weapons had been launched against them before, caused the men to jostle each other through the doorway in their haste to escape from possible hurt from the same source.

Scarcely had the last man disappeared before Juana was down the stairs like a flash, had slammed-to the heavy oaken door, and had drawn the great iron bolts and the heavy iron bar across it.

"The master left it open when he went out this morning," she said to Inez, "and I never thought to shut it. Why should I? That is how they got in so easily; but they will not get in again so fast!"

This was true enough; for the door had been made to withstand attack, as, indeed, had the tower itself, and though it had fallen into a ruinous state inside, it was built in a very solid fashion, the walls being exceedingly thick, and light being admitted mainly by loopholes. The top, also, was protected by a low battlement, from which a view of the surrounding country could be obtained. This battlement had fallen a good deal into disrepair, like the tower itself, and material for repairing it had been brought in; so that not only had the girls the remainder of the stones they had already used with such effect, but there was a large quantity of such material that had been laboriously carried up to the very top only three days earlier; and some of these stones were very large and heavy, as they had been designed to form the coping of the battlement.

"See there!" cried Inez, as the two girls ran up the stairs to the top, to watch the retreat of the temporarily baffled foe. "Juana, how long, think you, would such artillery last us? We could slay a score of our foes, as the woman in the tower slew Abimelech the king. Did not mine uncle tell us that tale the other night? and how little we thought——"

Juana's eyes were shining. The thrill of victory was upon her. The peril was not over. Nay, they might have worse to encounter than they had done already. But at least they had driven forth the foe from the tower. Their citadel was their own. They had weapons of defence under their hands. If help would only come at last, they could hold out for awhile.

"See, see!" cried Inez, as she leaned over the wall to watch the baffled Moriscos wending their way downwards, sometimes turning to shake threatening fists at the tower and its defenders. "There is little Aluch hiding below in the orange grove, and making signals to us. Run, Juana, to that loophole below, and he will tell you what he has come to say!"

Juana disappeared down the stairs, and returned quickly with a face in which anxiety and satisfaction were strangely blended.

"The master has got safely off to the mountains. He will be at Marbella very soon, and then they will start out to help us; but Aluch said he heard the Moriscos vowing vengeance upon us as they went away. They will quickly be back; and he thinks if they cannot batter in the door and take us alive, that they will burn the tower down over our heads."

"They will if they can," said Inez, looking out over the fair, wild valley, with the expression of one who knows she may be looking almost her last upon a familiar scene; "but we have a welcome ready for them!"

They leaned over the battlements, those two brave-hearted girls, and they watched the little village at their feet, almost wishing that the Moriscos would show themselves; for suspense was harder to bear than action.

"Let us say our prayers," said Inez, suddenly kneeling in the hot sunshine upon the hard stone floor; and Juana instantly knelt beside her and took her rosary in her hands.

When they rose from their knees a few minutes later, suspense was at an end. The attack was approaching.

"They have weapons now!" cried Juana. "Mistress, have a care. Those bows and arrows are deadly weapons in the hands of a good marksman. And look—they are bringing faggots; and that mule has a barrel of tar upon his back! And see that great ram of wood! They will seek to batter down the door with that. If they do——"

Yes, if they did that, the girls' position would be desperate indeed. Before, the men had only been armed with daggers and scimitars, which were useless save at close quarters. Now they had the deadly bow and arrow, and if they once obtained entrance, it would be useless for the girls to repeat the defensive manœuvre of the earlier hours. They would be shot down instantly, and fall an easy prey. Inez realised that in a moment, as she watched the approach of the Moors; and scarcely had her head appeared above the battlement, before a shower of arrows fell clattering about them.

"This side!" she said to Juana, between shut teeth. "They will try the door first; we will be ready for them!"

The girls dared not show themselves openly; but the battlements were built with a view to defence, and they were able to look cautiously over without being seen. The Moors were approaching the door; they were almost directly underneath.

"Now!" cried Inez, setting her hand to a huge stone. Juana put all her strength into the task, the great coping stone was hoisted between them, and pushed bodily over.

A fearful yell and a thundering crash told that it had done its work well; a storm of furious execration went up, and in the midst of it down came another stone which dashed out the brains of a fellow in the crowd below.

Juana peered over and then drew back, a fierce triumph on her girlish face; for she had seen that there were two enemies the less.

"We have plenty of stones, the saints be praised!" she exclaimed. "They are closing in again, Mistress. Let us give them another!"

The Moors were always careless of life in battle; and again and again they advanced to fix their battering ram; whilst again and again the huge stones came thundering down, and, besides these large ones, were many smaller, which the girls aimed with such precision and coolness, that not only could the assailants not fix their ram against the door to batter it down, but the men approaching the walls with faggots and combustibles were picked off one by one, and dropped wounded or crushed beneath the hail of stones from above.

Inez looked over once again, drawing herself up to her full height, and straining her eyes towards Marbella in the hope of seeing the long-looked-for relief.

"Have a care, Mistress, have a care!" cried Juana anxiously, and sprang forward; but she was just too late. The arrow had buried itself in the shoulder of Inez; she gave a start and an exclamation of pain; but, taking hold of it firmly, she instantly plucked it out.

"Pray heaven it be not poisoned!" cried Juana, as she stanched the flow of blood with quick, skilful fingers. And Inez smiled bravely through her pain.

"Hark! They are at the door again; we must show them that the garrison is not disabled yet. That stone there, Juana; now both together! down it goes! Hark! what a yell that was. I am revenged for my sore shoulder!"

But the brave resistance of the girls seemed rather to stimulate than to baffle the assailants. The air was rent with frightful threats and curses; and Inez, looking rather white, though there was no fear in her heart, said quietly:

"There is no hope of mercy, Juana. If we are not relieved; if help comes not, we must sell our lives as dearly as we can; and plunge our daggers into our own hearts sooner than fall alive into their hands."

"We will, Mistress," said Juana firmly. "But surely our Lady will send us aid ere that!"

"Look! look! look!" cried Inez suddenly. "The banner of the cross! Oh, Juana, do my eyes deceive me? Is it a vision that I see?"

And indeed for a moment both the girls thought that it must be; for the light fell sparkling upon mailed headpieces and flashing swords; and a banner with the cross flaunting in the golden light of the southern afternoon was borne aloft, and waved as though in signal that help indeed was at hand.

"What can it be? Whence come they?" cried Inez, with breathless agitation. "That is not the road from Marbella! Our Lady herself must have sent them to our aid! Pray heaven it be not a vision!"

"See, see!" cried Juana in ungovernable excitement, running to the battlement and showing herself fearlessly. "The Moriscos—they run! They fly Mistress, we are saved! We are saved! It is our brave Spanish soldiers come to our rescue!"

Inez looked over in turn, and though the mists seemed to rise before her eyes in the revulsion of her feeling, she could see the flying figures of the Moriscos dashing down helter-skelter into the deep ravine below, to escape the Christian swords, and she saw the lifted headpiece of the officer in charge of the band, as he looked up and marked the two girls leaning over the low rampart.

The next minute Juana had dashed down and opened the door, while little Aluch, flushed with triumph, was telling Inez how this band had come in pursuit of the rebels of Orgiba; how he had met them and told them of the predicament of the Christian maidens, and had brought them by the nearest route to the rescue.

So Istan was saved—saved from Spanish vengeance through little Aluch's act, as the Christian population of three souls was saved by the heroism of the two brave girls. Inez rode into Marbella that evening beside the officer of the band, to find her uncle there, beseeching help, which the citizens could not believe was wanted in such a peaceful spot, till the young officer rode into the great square, still holding Inez by the hand, and told the tale of how she and Juana had held the tower against the rebel Moriscos.

CATHARINE THE ROSE

He held her hands and looked steadfastly into her eyes.

"You would not hold me back, Kate?"

The eyes which looked bravely at him were full of tears; but the girl shook the drops from her long lashes as she threw back her head, and spoke with unfaltering lips.

"I would hold no man back from his duty; least of all the man I love."

In a moment his arm was about her. The troth plight, spoken amid the clang of arms and the rattle of musketry, was but three days old; and the strange sweetness of it had penetrated the life of the English Captain in a fashion which he had no skill to analyse. But in these stern days there was little scope for the sweetness of spoken love; and even the minutes snatched from the pressing needs of garrison life were few and far between.

But Hart had volunteered the second time for a service of extra peril, and he had come to speak a farewell to his love—a farewell which both knew might be final.

"I went and returned in safety last time, sweetheart," he said, "and wherefore not again? I shall have your prayers to Heaven on my side this time."

"You had them before," said Kate, lifting her head from his shoulder and looking straight into his eyes; and he kissed away the last of the raindrops from her lashes.

"Help we must have if Sluys is to be saved," he said. "I swim forth to-night, under cover of the darkness, with letters for England's Queen. The devil take that pestilent peace-party, who would beguile her into dallying with Spain and her tyrant King and treacherous Princes!" broke out the young Captain suddenly, in a gust of hot anger. "Can she not see that her only safety lies in joining heart and soul with the Netherlands in their struggle for life and liberty? Let Philip of Spain once get these lands beneath his iron heel, and then England will have cause to tremble for her very existence!"

"But the Queen has sent us help already," said Kate; "surely she will do more, when she knows our dire extremity!"

"Eight hundred men," answered the young officer, with a tone of scorn, "eight hundred English soldiers with eight hundred Dutch, to hold a place like Sluys! How is it possible the thing should be done? It has come to this, that if help comes not, Sluys must fall. Alexander Farnese and his Spanish host will score another triumph for tyranny and the Inquisition!"

A shudder ran through the girlish frame at the sound of that word, more hateful and terrible to the party of freedom than any other which could be spoken. Then her eyes flashed with a spark as of fire, and, flinging back her head, she cried:

"And what would the men do if they came, Harold? What work would you set them first to do?"

"There is work and to spare, both in attack and defence," answered Hart, with something of grimness in his tone. "We are in dire need of at least four redoubts between the citadel and the ramparts. The burghers have banded themselves together to build us one. We are sending every man that can be spared from garrison duty and the actual fighting to throw up the second; but how the others are to be constructed with our present force it is impossible to see. Help we must have at all cost, and I trust these dispatches which you have been so carefully sewing in my clothing, will bring it to us, ere it be too late."

He could not linger. The shadows of the coming evening were beginning to fall, although the summer day lingered long. He put his hands upon the shoulders of the girl, and looked into her face with a long wistful gaze. His own face was very thin and brown, and though he was still quite young, there were a few grey hairs to be seen about his temples. Hard living, hard fighting, days and nights of anxious toil had left their impress upon him, as upon many another compatriot at that season of bitter struggle. And the bitterness was greater rather than less for the knowledge that if England's Queen and her counsellors would but show a little more firmness of purpose and readiness of dispatch, many of the horrors of this protracted struggle might even now be saved to the courageous and devoted Dutch.

Even upon the fair young face of Catharine Rose, the perils in which she had been reared had traced their lines. That look of firm determination, of high-souled courage, of resolute devotion to duty, be the cost what it might, could not have been so clearly written there had she not lived her young life amidst scenes and tales of stress and storm.

Men and women, youths and maidens, had to face from week to week, and even from day to day, the possibility of having to yield up life and liberty, home and friends, for their fidelity to their country and their faith. Catharine's father had died a martyr at the stake. Her brother had been slain in the memorable defence of Antwerp, two years since; and the loss of her only son had broken the mother's heart, so that she faded away and died a few months later.

But these troubles and losses had broken neither the heart nor the spirit of Catharine. She had the mixed blood in her veins of an English father and a Dutch mother; the courage and devotion of two warlike nations seemed to combine in her youthful frame.

Her quarrel with Fate was that she had been born a woman, and not a man. Her longing was to gird on sword and buckler, and go forth to fight the hated Spaniard—the tool of the bloody tyrant whose very name was not heard without curses both loud and deep.

"Oh, if I were but a man!" had for long been the cry of her heart; and if in the sweetness of feeling herself beloved by one of the heroes of Sluys she no longer breathed this aspiration, it was not because her heart was less filled with an ardent longing to do and to dare.

"Farewell, sweetheart," spoke the Captain, looking deep into her eyes, and knowing, as she too knew, that perhaps he was looking his last. But the consciousness of ever-present peril was one of the elements of daily life in the beleaguered city; and although this mission upon which Hart set forth was one of more than ordinary peril, a soldier never went forth upon his daily duty with any certainty of seeing home or friend again.

"Farewell; God be with you, and bring you safely back to us," she answered steadfastly; and their lips met once before he dropped her hands, and hurried away without trusting himself to look behind again.

Catharine looked after him from the window as he walked rapidly away in the gathering twilight. Her accustomed ears scarcely heeded the sullen booming of the great guns, or the dropping shots of muskets from the ramparts. The life of the town went on with a curious quietude in the midst of warlike strife; notwithstanding the fact that it became daily more and more evident that without substantial succour in men, and munitions, and food, Sluys could not hold out against such overmastering odds.

Suddenly the girl turned from the window, and, with fleet steps, crossed the room, descended a dim stairway, and entered the chamber beneath, where, by the light of a solitary lamp, a girl, a few years her senior, was setting out a frugal meal with the aid of a youthful servant-maid.

"Has he gone, Kate?" she asked, as she saw that Catharine was alone; "I had hoped he would have had something to eat ere he sallied forth into the night. The rations of the soldiers are meagre enough now, and he has a hard task before him. God in His mercy give him safe transit through those sullen waters, and blind the eyes of sentries and soldiers!"

"He could not stay," answered Kate, "and he said he had eaten well. May," she broke out suddenly, clasping her hands together, the colour coming and going in her cheeks, "May, I have a plan, and you must help me. I have learned what the sons and daughters of the city can do for Sluys. I am going to toil for her, and you will help me!"

"What mean you, Kate? What have you heard? What can be done for the city by weak women like ourselves?"

"I am not a weak woman!" answered Kate, throwing back her head in her favourite gesture, "I am a strong woman, and so are you, May, and so are dozens, ay, and scores of the daughters and the wives of the burghers. Listen, May. You know of the need for redoubts, and how your husband is toiling almost day and night to construct one on yonder side of the citadel. But they need more; Harold himself told me so. They need more than soldiers or burghers can build. I am going to organise a band of women and girls. You and I, May Hart, will be the leaders. I have not watched the building of forts and defences for nothing all these weeks. You and I with the women of the city, will build them a redoubt, and it shall be the work of the girls of Sluys!"

The young wife fired instantly at the suggestion. All over the city it was known of the dire want of men to construct these defensive works. Boys and men of the burgher class had gone forth willingly in defence of their town, and were working night and day at the unaccustomed toil.

But Sluys was to see another sight ere long: a great band of women, many of them mere girls, and even little children, armed with the needful tools led by Mary Hart and Catharine Rose, going forth morning by morning from their homes, delving, building, toiling through the long hot summer's day, in rivalry of the brothers and fathers on the corresponding side of the citadel; the new redoubt rising bit by bit before their strenuous efforts, the work as accurate and solid as that of the men, though every detail was the work of women and girls.

"Impossible!" had been the first cry of the burghers when they heard of the proposed scheme. Proud though they were of the spirit that inspired their women-kind, they shook their heads at the thought of their ever being able to carry out such a plan. But Catharine was a power amongst the girls of Sluys. She came of a race who had laid down their lives for the country of their adoption. Her mother had been a townswoman; and the girl had been born and bred amongst them. "Catharine the Rose" she had been called in affectionate parlance, a play upon her patronymic, and a compliment to her brilliant colouring which even the privations and anxieties of the siege had not dimmed.

Mary Hart was also a girl of Sluys, lately wedded to Roger Hart, the elder brother of the gallant English Captain, who had been sent with the small band of troops into the city a short time previously, and had already so distinguished himself by personal courage, that any specially perilous errand was readily entrusted to him.

Roger was not a soldier by profession. The Harts' father had settled in the Netherlands during a time of Tudor intolerance and persecution in England, little foreseeing how soon the land of their adoption would become the arena of a struggle to the death against a tyranny of which England in her worst and darkest hour had never dreamed. He had, however, thriven and prospered in the country he had chosen as his home, and had not been driven away by the troubles which speedily befell it. His sons, like Catharine Rose, combined in their veins the blood of England's sons and that of the Netherlands; and it was with the Harts that the girl had found a home, when her mother's death had left her alone in the world. Perhaps it was not strange when Harold Hart came to Sluys and spent his few spare hours at his brother's house, that he and the girl he had played with in childhood should draw together as they had done, animated by a common love, a common hatred, and a common steadfast resolve to do and dare all in the cause which was nearest their heart.

But how would the amazons of Sluys face the fire from the guns of the enemy when their earthworks grew to the height that would make them increasingly a target for the Spanish guns?

"Leave it to us now," said some of the burghers, who came as a deputation to the spot where the women and girls were at work. "Commence the fort if you will, brave maidens, but leave this part to men. It is too stern work for delicate girls when the storm of lead whistles about those who work."

It was to Catharine the Rose they spoke, and she turned upon them with a flash in her eyes, as she made answer:

"Think you that we have not counted the cost? Think you that we are afraid? Have we not seen? do we not know? Are we of different nature from yourselves? I answer for the maidens of Sluys. That which we have begun we will carry through. Have not you men your work cut out? Are you not toiling—ay, and dying—daily for our defence and that of our homes? Do you think we are afraid to toil, and, if need be, to die in the same cause? It was like you to offer thus to relieve us in the time of chiefest peril; but I give you the answer of the girls of Sluys—go to Captain May for the answer of the wives!"

Captain Catharine and Captain May were the titles by which the two leaders were known to their own squads; but the men called them "Catharine the Rose" and "May in the Heart"—a sort of graceful parody upon their names.

Mary Hart had the same answer to give on behalf of the wives of the burghers. And, indeed, it was abundantly evident that the men had their hands full with what they themselves had undertaken, and that unless the brave work were carried out by those who had commenced it, it must perforce be abandoned; whilst more and more needful for the safety of the city did these redoubts become.

The temper of the besiegers was known to be sorely tried, and scant was the chance that even if they heeded the sex of the workers upon the growing redoubt, they would on that account permit it to grow without opposition. Again and again in the history of those bloody wars women had fought side by side with men in the defence of their homes and liberties, and the Spanish soldier had as ruthlessly cut down the one as the other.

"Girls, are you afraid?" asked Kate, as she led forth her band upon the morrow. "You have heard the balls hissing overhead these many days; but to-day, perchance, we shall feel the sting of the hot bullet, or the splinter of some shell tearing its way into our flesh. Are you afraid to face such experience?"

"We are not afraid; where you lead us, we will go!" was the almost universal rejoinder, spoken with a quiet gravity and resolve which attested its sincerity. These girls were not undertaking the task in ignorance of its perils. They had seen enough of wounds and death. They knew what they were facing; but there were only a few waverers who, on Kate's invitation, went back; and even they could not tear themselves away from the scene of their labours; they came to look on beneath the shelter of the rampart, to give help should help be needed; and before long the stern excitement of the hour possessed them also, and scarce one but was soon working with the rest, only shrinking and perhaps uttering a little cry as some bullet might whizz close to her ear.

Under fire!—a rain of bullets falling round!—a comrade beside you sometimes falling silent and helpless, or with a cry and a struggle. It is so easy to speak of such things, but how many of us realise what they mean to those who have passed through such experience?

Catharine in the foremost post of danger worked on directing and encouraging. She had insisted that her squad of girls should take the side most exposed to the enemy's fire, leaving the less perilous place for the married women. There had been a generous rivalry for this position of peril and honour; but Catharine's word and determination had prevailed.

"You who have husbands and perhaps children to think of, and to miss you if you are taken, must give this post to us," she said; and she thought of the man she loved, of whom no tidings had yet come; who had ventured his life so many times; and in her heart she prayed that if he were taken, she might join him on the other side of the narrow stream of death, the stream which seemed so small and narrow when so many were crossing it day by day.

So the work progressed rapidly, though many a brave young life paid forfeit, and the tears would well up sometimes in Kate's eyes, as she saw a comrade carried off dead, or bent over a dying girl, to hear her last brave message for home and friends; or, when in the silence of the night, she thought upon these things, and cried in her heart, "How long, O Lord, how long?"

But there was never a quiver of fear in her face or in her heart as she stood to her post day by day; and the walls grew, and the Commandant of the garrison came and gave warm praise and thanks, and timely cautions and instructions to the heroic girls who toiled through the hot summer days without one selfish thought of fear.

Once, as he stood beside the leader of these brave young amazons, a shell came screaming through the air, and he shouted a word of command.

"Down on your faces!" he cried, and himself set the example, to show them what to do. The shell was from a new battery, and it had been directed with a view to stopping the work on this very redoubt. The girls dropped their tools and fell flat, but Catharine was a thought too late. She had been so interested in the work of that battery that she forgot for a moment the peril in which she stood. Luckily the Commandant pulled her down beside him before it was too late; but a portion of the explosive struck her, tearing a ghastly wound from wrist to elbow. The stones and rubble seemed to fly up around them; a fragment dashed itself against Catharine's head; a blood-red mist seemed to swirl before her eyes, and blank darkness swallowed her up.

When she opened her eyes next it was to find herself at home, lying upon the wide couch beneath her favourite window which looked down the street. The light showed that the evening was advancing; May was in the room setting the table for supper, and—but was not that part and parcel of the dream which still seemed to enwrap her faculties?—Harold, her bronzed-faced soldier, was seated beside her, his eyes hungrily bent upon her face.

She smiled, half afraid to move lest the dream should vanish, and the next moment he had her fingers close in his grasp.

"Kate, my Kate!" he cried; and she smiled back, and sat up.

The Commandant pulled her down beside him before it was too late.

The Commandant pulled her down beside him before it was too late.

Page 30.

"Harold! you have done it again! and have come back safe."

"Yes, I have come back, and to find—what? That my Kate has set an example to the women of the Netherlands, that——"

But she put her hand upon his mouth and stopped him.

"It was not I more than others; and there are some who have laid down their lives for the cause. You must not praise me; why should not women do their duty to the cause of freedom as well as men? You do not praise your men for standing to their guns."

"But we will praise you!" cried Harold hotly. "Know you not that all the city is ringing with the news that the women's redoubt is all but finished, and that in spite of the deadly fire from the new battery? And Kate, to-night the soldiers will get the guns mounted, and to-morrow Fort Venus will give her answer back. Oh, my Kate, will you be able to come and see?"

"Fort Venus?" she queried, with a smile in her eyes.

"That is what the Commandant has christened it, and the soldiers received the name with ringing cheers. The names of Catharine the Rose and May in the Heart are in all men's mouths. Surely, surely you must be there to see!"

And she was; for the wound, although severe, was not crippling, and the dauntless spirit of the girl carried her through the triumph and gladness of the next day, as it had carried her through the previous perils and hardships.

A spectator would have thought that Sluys was en fête that day instead of a sorely pressed beleaguered city, wanting food, help, everything. Citizens and soldiers marched in squadrons to the new fort, which had been the scene of arduous toil all the night, and from whose loopholes the mouths of guns could now be seen protruding.

And foremost in that procession, cheered to the echo by burghers and soldiers alike marched the brave women and girls, who had done such work for their country and their city, headed by Mary Hart and Kate Rose.

Then, at a given signal, "Fort Venus" opened her mouth and roared forth her message of defiance and resolve.

"Hear the voice of the women of the Netherlands!" cried Arnold de Groenevelt, the grave Commandant, as the guns belched forth fire and smoke, and the welkin rang with the shouts of the citizens and soldiers. And so true was the aim of the gunners, that the new battery was speedily silenced; and cheer after cheer went up as the destruction wrought became more and more visible; and the youths of the city bore aloft upon their shoulders through the streets to their homes, Catharine the Rose and May in the Heart, crying aloud as they took their triumphal way: "Hear the voice of Fort Venus! Hear the voice of the women of the Netherlands! Death to the tyrant! Life and immortality to the liberties of the people, and freedom of faith. The voice of the girls is the voice of the nation."

ELSJE VAN HOUWENING

For two years she had lived within the walls of a grim fortress; a prison had been her home. Thirteen massive doors, secured by iron bolts and bars and huge locks, stood between her and the outer world; and yet this maiden of nineteen summers was no prisoner; she was here in this gloomy place of her own freewill.

And for what cause was she here? Was it to guard and tend one who was very near and dear to her,—a father, a mother, a brother? No; it was none of her own kindred who were thus shut up, but her master, Hugo de Groot, or Grotius, as he is more generally known to history.

With the causes for the unjust captivity of this great and learned man, we need not deal here. They belong to the page of history, where they can be read in full. Suffice it to say, that Grotius was condemned by the States-General of the Netherlands to a life-long captivity in the great fortress of Loevenstein, under the spiteful tyranny of its governor, Lieutenant Deventer, who had an especial grudge against him, and seemed resolved to make his captivity as bitter as it was possible to do.

The one grace allowed to the unhappy prisoner was that his wife and family might share his captivity; might live within the fortress in the quarters allotted to him, although not suffering all the rigours of imprisonment. And with Madame de Groot and her family of children had come Elsje van Houwening, their young maid-servant, who had stoutly refused to leave them in their hour of trial and trouble, and had already spent two years of her young life within the walls of the prison.

The tie that binds master and servant together was stronger in those days than it is now. The race of devoted servants seems well-nigh extinct in these degenerate days; our mothers and grandmothers had experience of a fidelity which is seldom met with now. But even in their times an instance of such courage and devotion must needs be rare. Yet to Elsje it seemed perfectly natural to cleave to the family that had befriended her in a lonely childhood, and she loved her master and mistress and their children with a love which only grew stronger and stronger during the long, monotonous days of this captivity. Small wonder was it that Madame de Groot should sit for hours over their scanty fire, her children asleep, her husband poring over the books which came to him from time to time in a great chest from friends in Gorcum, talking with Elsje as though to a friend, talking over the difficulties of keeping house upon the pittance allowed them from the Government after the sequestration of their family property; the mournful future that seemed to stretch indefinitely before them, and now and again of that ever recurrent dream of hapless prisoners—the chances of escape!

And yet what was the possibility of this? How could it be even dreamed of that a closely guarded prisoner should pass through those thirteen iron-bound doors which lay between him and liberty? And if the sad-eyed wife or eager maid looked down from their windows, what did they see, save the rushing, tumultuous flow of a deep turbid river?

Nature and art had combined, as it seemed, to make this fortress impregnable alike from without and within. It stood in the very narrow and acute angle, where the strong and turbid Waal joins its rushing waters with those of the Meuse; and on the land side immensely strong walls with a double moat guarded it from attack, and held in helpless captivity all those upon whom the great doors had closed.

True Madame de Groot with her children, or Elsje with her market basket, were permitted to sally forth at will by day, or, at least, under modified restrictions; to cross by the boat to Gorcum, which lay exactly opposite on the farther bank of the Waal. They made their purchases here, and saw their friends from time to time; but how did this help the prisoner? Madame de Groot was very stout and somewhat short, whilst Grotius himself was tall and slight, possessed of singular personal beauty, and an air and bearing that would be most difficult to disguise. The idea of dressing him up in their clothes, and smuggling him out in that fashion, had been talked of a hundred times, but only in a sort of despair. Hugo himself had shaken his head over the plan. It was doomed to ignominious failure, as he saw from the first. No one was permitted to leave the prison save in broad daylight, and all had to pass innumerable guards and sentries on the way. If the prisoner were to be detected seeking to escape in such fashion, it would only lead to a more rigorous and harsh captivity, and, probably, to his entire separation from his family.

The wife had sorrowfully agreed that it was too great a risk to run; yet, nevertheless, she and Elsje were ceaselessly racking their brains to think out some plan whereby the prisoner might escape the dreadful doom of life-long captivity.

It was evening. Madame de Groot was bending over the stove, cooking her husband's frugal supper. Elsje went in search of the children, to put such of them to bed as were not already there.

Her favourite out of all the little ones was Cornelia, a lovely little girl of nine years, wonderfully like her father, and perfectly devoted to him. She and her brother Hugo were often to be found in the room in which he studied and wrote from morning to night, only varying his sedentary pursuits by the spinning of a huge top that had been made for him by friends in Gorcum, that he might not suffer too greatly from lack of accustomed exercise.

Elsje stole softly into the room, so as not to disturb her master, and glanced round the bare place again and again. Where could the children be? She had looked everywhere else in their limited quarters; there was no other room except this one that had not been searched through and through. She would not disturb her master by a question, and continued softly moving and looking about, till the sound of a suppressed child's laugh, close beside her, made her almost jump; for there was nothing to be seen, save—ah! yes; she saw it all now—there was the great empty chest that had brought the last load of books from Gorcum. She raised the lid, and a simultaneous shriek of laughter arose from two pairs of rosy child-lips. There were little Cornelia and Hugo, curled up like dormice in the chest, peeping at Elsje, with eyes brimming with laughter.

She carried them off, laughing herself, and asking them how they managed to breathe with the heavy lid closed fast down.

"Oh, there is a long crack just under the top of the lid, it doesn't show from outside; but we could see light, and your shadow came right over us, and then Hugo laughed, and you heard. We sat there a long time this afternoon and told ghost stories. It was such fun!"

Elsje put the children to bed, and went thither shortly herself, but all the night long she was dreaming, dreaming, dreaming. She saw the chest with the two children inside; and then she saw it again, and instead of two small figures there was one large one—a tall man's figure crushed together in the chest, and when he turned his face towards her it was the face of her master!

The girl was up and about with the dawn; and her mistress coming to help her, she told her in whispers of the incident of the previous night and of her dream, and the two women stood staring at each other, with white faces and glowing eyes, as the idea slowly formulated itself and took shape.

"It might be done! It might be done!" whispered Madame de Groot at last; "if he could get in, it might perchance be done. Oh! if heaven should open us such a way as that!"

That day passed like a dream to all. They waited till dark; till all the children were sound asleep, and no one from without would trouble them again, before they even dared to make the experiment. Grotius was a tall man, as has been said, though he was slender in his proportions. At another time he would have pronounced it impossible that he should so fold himself up as to get inside that chest, and let the lid be fastened down upon him. But when a man sees life-long captivity before him on the one side, and the hope of escape and freedom on the other, he can sometimes achieve the impossible. And, at last, after many efforts, the thing was done; the lid was closed, and the man found that he could breathe and endure the pressure even for a considerable period.

Day by day, or, rather, night by night, he made these trials till his limbs in some sort grew accustomed to the strange constriction, and he was able to bear the cramped posture for a more prolonged time. Madame de Groot, upon her next journey into Gorcum, spoke jestingly with a friend as to how her husband would be received were he to turn-up some day, and Madame Daatselaer answered, in the same jesting spirit, that he would have a warm and hearty welcome; for the Daatselaers were old and tried friends, though only of the rank of merchants. They owned a large warehouse of great repute, and their dwelling-house was at the rear of the shop, where ribbons and other merchandise were vended to all comers.

It was through the immediate agency of these friends that the books lent to Grotius by Professor Erpenius were consigned to him in his prison. The Professor sent them to the Daatselaers, who dispatched the chest by the boat which plied between Gorcum and the fortress opposite. It was returned in the same manner to them when the books were done with, for transmission back to the Professor. Therefore, if Grotius could conceal himself in the chest for the journey over the water, he would be consigned to the safe-keeping of friends, who might be trusted to do everything in their power to facilitate his escape to Antwerp, and so to France, where he would be safe from the malice of his enemies.

Days flew by, and the plan seemed more and more feasible, albeit fraught with no small danger of discovery. Madame de Groot's anxiety was almost greater than that of her husband, and perhaps it was her visible agitation, occasionally manifesting itself in spite of her great courage and self-control, which led the prisoner to speak as follows to Elsje, when he and she were alone one day, his wife having gone once more to Gorcum, prepared to drop a faint hint to Madame Daatselaer, without, however, really arousing her suspicions of what was in the wind; for all knew how much the success of such a scheme depended upon the maintenance of absolute secrecy.

"My good girl, is it true what thy mistress says of thee, that this whole plan is one of thine own making?"

"Not of my making, master, but rather as a thing revealed to me in a dream. I seemed to see the chest, and when it was opened there was my master within. I told the dream to my mistress, and the rest seemed to follow of itself."

"And if the plan be carried out when next that chest is returned, who will accompany it across the water?"

Elsje paused in thought. Sometimes she had gone with it on former occasions, sometimes her mistress. There had been no peril in the transit then. It had mattered nothing who went; but now things would be quite different. She looked her master questioningly in the face. He returned her glance.

"I have been thinking much on that point," he said; "it will be a memorable journey for those concerned. There be moments when I misdoubt me if my wife hath the needful firmness. It is not courage that she lacks, nor firmness of purpose; but can she pass the many barriers, the many posts of peril, the many prying eyes within and without, and so command her face that her anxiety be not seen? The sorrows and anxieties of these last years have told upon her. And if she betray too great solicitude for this chest of books, why in a moment we may be undone!"

Elsje stood looking very thoughtful. She saw at once the danger of self-betrayal; the danger that would be far more quickly noted in the prisoner's wife than in his servant. Her gaze was lifted to her master's face.

"Shall I be the one to go?" she asked.

"Wouldst thou not be afraid, my child?"

"What punishment could they give to me were the plot to be discovered?" she asked.

"Legally none," answered Grotius, whose training in the law gave him full knowledge on all such subjects; "but, my girl, I myself am guilty of no crime—yet see what has befallen me. I cannot tell what might be thy fate were this thing discovered during the perilous transit."

For a moment Elsje stood motionless, thinking deeply. Then she lifted her head, and her eyes shone brightly.

"No matter for that," she said, "whatever comes of it I will be the one to go. If they must punish another innocent person, let the victim be me rather than my dear mistress!"

Grotius took her hand, and the tears stood in his eyes. Elsje rattled on as though to hinder him from speaking the words that for the moment stuck in his throat.

"It will be better so every way," she said, "for see—the men must come in hither to get the chest, and so it must seem that you, master, are sick and in bed, else would they look to see you here at work. We must draw the curtains close; but leave your clothes visible by the bedside, and my mistress must seem to be attending upon you. So it will be best every way for me to go with the box; and the soldiers all know me, and we have our quips and jests together. I will talk to them all the while, as my mistress could scarce do without rousing suspicion, so they will not note if the weight of the chest be something greater than usual."

"Thou art a brave girl; thou hast a great heart and a ready wit," said the prisoner with emotion in his voice, "may God reward thee for thy devotion to a family in distress; for we may never be able to do so."

"I want no reward," answered Elsje stoutly, "save to know that I have helped those I love, and who once befriended me."

The next day was Sunday, and a wild March gale was raging round the castle, lashing the waves of the river into foam. The rain dashed against the windows as they sat with their books of devotion, as usual, through the earlier hours of the day. Grotius had read and offered prayer as was his wont, when suddenly little Cornelia turned her face towards the barred window, and her eyes seemed full of a strange light.

"To-morrow, Papa must be off to Gorcum, whatever the weather may be," she said; and then, slipping off her chair, took the little ones away with her for the usual midday repast.

Husband and wife looked at each other aghast. The strangeness of the coincidence seemed to them most remarkable.

"Let us take it for a direction from heaven," said Grotius. "Out of the mouth of babes and sucklings—the child knew nothing, yet something was revealed to her spirit."

Later in the day Elsje came breathless with the news that the Commandant of the fortress was just leaving it for a few days' absence. He had received his captaincy, and was to go to Heusden to receive his company. All things seemed pointing in one direction; and early on Monday morning, Madame de Groot asked leave of Madame Deventer to send back the chest of books to Gorcum.

"My husband is not well; he is wearing himself out with so much study. If the books are sent away I can persuade him to remain in bed and take some needful repose. I got him to pack them up last night; but if they stay in his sight, he will assuredly remember something more he wants to study, and nothing I can say will then persuade him to keep in bed."

Madame Deventer was a kind-hearted woman, and sorry for the prisoner's wife. She gave ready consent to the request, and said she would send some soldiers shortly to take the chest away.

The crucial moment had come. Grotius, dressed in the thinnest linen under-garments—for there was not space for much clothing—took his place in the chest. A book, padded with a cloth, served as a sort of pillow, a few books and papers were placed in such interstices as were left by the curves of his body; and his wife took a solemn farewell of him before she shut down the lid and snapped the key in the lock, giving it in deep silence to Elsje.

Outside the storm still raged and howled, but the tumult of their souls seemed greater; yet Elsje stood with a careless smile on her face as the soldiers entered the room, and Madame de Groot bent over the fire, stirring something in a saucepan, and telling her husband that she would soon have his soup ready, and she hoped he would enjoy it more than his breakfast. The curtains of the alcove bed were drawn, and the ordinary clothes of the prisoner lay upon a chair near it.

"My word, but it is a heavy boxful this time!" exclaimed the men, as they laid hold of the chest.

"To be sure," cried Elsje; "what would you have? They are Arminian books, and those are mighty solid, I can tell you. You had best have a care how you treat them when you get to the water. Arminian books have sunk many a good bark ere now, before it has got into harbour!"

The men laughed at the innuendo of the girl's words. It was in truth their adherence to the Arminian side of the great Arminian and Calvinist controversy which had shipwrecked the lives of Grotius and so many others. Elsje chattered gaily to them as they dragged and lifted the heavy chest down the stairs and through the thirteen ponderous doors. She kept them laughing by her droll remarks, and the little anecdotes she retailed for them whenever a halt was called. At last it stood without the last of the doors, and the soldiers paused and wiped their brows.

"Is the chest to be examined before it goes on board?"

Elsje's heart thumped against her ribs. This was the crucial moment. At first when the box had gone in and out its contents had been carefully examined; but as nothing save the books had ever been found there the practice had been given up latterly. But there was never any actual certainty.

Elsje dangled the key from her girdle, and swung it carelessly round and round.

"It always used to be done," she said, "but methinks my lord Commandant love not the smell of Arminian books; perchance it smacks too much of brimstone to please him! For of late he has not troubled. But I care not, only pray you make haste. I have marketing to do in Gorcum, and what if all the best things are sold ere I get there, and my poor master lying sick?"

"Is the chest to be examined before it goes on board?"

"Is the chest to be examined before it goes on board?"

Page 48.

"Ask the will of madame," said somebody; and the messenger went and returned, whilst Elsje stood almost sick with apprehension, though she never ceased laughing and talking the while.

"Madame says it may pass," came the answer back, "since her lord troubles not now, she will not delay the transit."

"Perhaps she fears lest some little Arminian imp should spring out upon her!" quoth Elsje merrily; and away they went with their load towards the boat.

It was indeed a rough passage that lay before them; and the girl's heart was in her mouth many times ere she got her precious chest safe on board, and securely lashed to keep it from slipping overboard. They laughed at her solicitude; but she always had a ready retort; and a young officer of the garrison, crossing at the same time, was so taken by her rosy face and bright eyes that he sat himself down upon the chest and drummed upon it with his feet, as he chatted with the little servant girl.

"Why do you wave your kerchief?" he asked, as the boat began her rough voyage across the tumbling waters.

"To tell yon children at that window that I am safe afloat. They feared the boat might not go in such a storm. And, fair sir, be pleased to leave kicking of that box, and come away to this better seat; for there is some precious porcelain inside, and if it be broken, I shall get the blame, for I packed it."

But Elsje's signal was for the straining eyes of her mistress far more than for those of the children. All was well thus far, and the worst of the peril was over; but—but there was still the landing on the other side.

"Take my box first," she pleaded, as they approached the wharf.

"That lumbersome thing?—that can wait till the last," answered the skipper, rather surlily; "'tis as heavy as if it held a man."

"I have heard tell how a criminal was once carried from prison in a box," remarked a soldier's wife laughingly, "and, methinks, if one has so escaped another might. Let us peep inside, maiden!"

Elsje laughed, bending to tie her shoe-string.

"What, and let the Professor's books be all scattered this way and that, and perhaps fall into the water! He would never send my master another chest; and, methinks, without books he would die."

"I'll get a gimlet and bore a hole in the Arminian!" laughed the soldier, whose wife had first spoken.

"Ay do!" cried Elsje; "get a gimlet long enough to reach the top of the castle. I will stand by and watch you as you bore!"

"Out of the way there!" cried the skipper and his son, as the boat swung towards the wharf; and in a moment all was bustle and confusion. The soldier helped his wife ashore, the young officer made a bow to Elsje and sprung over the side; there was hurry and bustle, and a welcome confusion; and the girl stood beside her precious chest, and at last, by the promise of an exorbitant fee, got the skipper and his son to transport the chest at once to the Daatselaers' house, on a barrow.

She walked a little ahead in her excitement; but was recalled by a surly question from the old man.

"Do you hear that, girl—do you hear what my son says? You have got something alive in that box!"

"Ah, to be sure, to be sure," she cried, laughing, "it is the Arminian books; they are often like that, because they say the devil helped to write them. Why, when I was a little girl I knew an old woman who lived all by herself in a wood; and she had a big book, and they said the devil had given it to her; and if she wanted a ride, she just got astride of it and it flew with her wherever she wanted to go! That's what my mistress says about some of these big books. There's magic in them, and she wants to be rid of them."

The men looked awed; but superstition was rife in those days, and their one aim now was to be rid of the uncanny load. It was wheeled, and then lifted into the back room of the house, and Elsje paid and dismissed the bearers with perfect calmness.

The next minute she had glided into the shop where Madame Daatselaer was serving customers, and whispered something in her ear.

Leaving everything, but with a face as white as paper, the worthy woman hastened after Elsje, who rapped on the lid, but got no reply; for a moment her fortitude gave way, and she cried aloud in her anguish:

"My master!—my poor master—he is dead—stifled!"

"Ah!" cried Madame Daatselaer in bewildered dismay, "better a live husband in a prison than a dead one at liberty; my poor friend, my poor friend!"

But a sharp rap on the trunk from the inside reassured them.

"I am not dead," gasped Grotius, "but I was not sure of your voices. Open and let me have some air!"

Elsje unlocked the chest, whilst her friend locked the door of the room, and Grotius raised himself slowly as from a coffin.

"Praised be God for this deliverance!" he cried, as Elsje brought a cloak in which to wrap him, for he was cramped and numbed by cold, and the constraint of his posture. "God be praised for His mercy; and how can I thank you enough, good friend, for receiving me thus into your house!"

"If only it bring not my husband to prison in your place," cried Madame Daatselaer, whose face was deadly pale.

"Nay, nay, sooner than that I will return to my prison in yon chest as I came forth!" answered Grotius.

But Madame Daatselaer rallied her courage and spoke quickly.

"Nay, nay, that shall never be since thou art here. But thou art no common person, and all the world talks of thee, and will soon be talking of thy escape. But before that we will have you safe from pursuit. My husband will see to that. And now I must hide you in the attics till dark, when we can make farther plans."

Elsje's work was done. Her master took her hands in his, and kissed her on the brow.

"Farewell, my brave maiden. May God reward you and keep you always safe from harm. There will be many heartfelt prayers offered that no ill shall befall you through your devotion to me and mine. And now go—tell the story to my dear wife; and so soon as I be safe in France she and the children shall join me, and in our home there will always be a place for thee; if thou dost not find another and a better home for thyself."

Elsje's tears fell as she said farewell to her master; but her heart was full of joy as she returned to the castle with the story for her mistress. And soon they knew that Grotius had effected his escape to France, and that all peril was at an end.

The Commandant, it is true, raged at the women when he found how his prisoner had escaped him; but nothing was done to them, and they were shortly released.

They joined their lord and master in his new home, and from thence one day, not so long after, Elsje van Houwening was married to a faithful servant of the family, who had also shared their captivity in the fortress of Loevenstein; and had been so well taught by his master the rudiments of law and of Latin, that he rose in time to be a thriving advocate.

But of nothing was he ever so proud as of the bravery and address of his wife in her girlhood, when she had been the instrument by which the celebrated escape of Grotius had been effected from the grim fortress of Loevenstein.

GRIZEL COCHRANE

Father and daughter stood facing each other in the gloomy prison of the Tolbooth: the girl's face was tense with emotion, and the man's eyes seemed to devour her with their gaze; for Sir John Cochrane believed that he was looking his last upon his favourite child.

He was not a man of great parts, nor one who can be regarded as in any sort a hero. He was more rash than brave, and his ill-judged support of the claims of the luckless Duke of Monmouth had brought him to his present doleful position—that of a prisoner in the hands of a deeply offended and implacable monarch, expecting each day to hear that his death-warrant had arrived from London.

Sir John had been one of the leaders of the insurrection in Scotland, which had been even more of a fiasco than the one conducted by Lord Grey in the West of England, where a temporary success at the outset had cheered and encouraged the adherents of the champion of Protestantism.

King James II., savage of temper and bitterly angry with all those concerned in this rebellion, had sent the terrible Jeffreys to the Western Assizes, which henceforth were to be known as the Bloody Assizes; and here, in Edinburgh, lay another illustrious victim, awaiting the king's warrant, which would doom him to the scaffold.

Whatever might have been his faults and errors in his public life, Sir John was a tender and loving husband and father. His wife, a delicate invalid, shattered by grief and anxiety, was unable to leave her room; but Grizel had come. Grizel had paid visits before this to her captive father, and each one was more sorrowful than the last, since the end must now be drawing very near.

"Methinks, my child," said the father hoarsely, "that this will be our last meeting on earth. They told me to-day that the death-warrant would, in all likelihood, be here in three days' time from this."

A quiver passed over Grizel's face; yet her voice was calm.

"Can our grandfather do nothing?" she asked.

Now Sir John's father was Lord Dundonald, a man of wealth and influence, and the question was a natural one to put.

"He is doing his utmost," answered Sir John, "I have had tidings of that. He has got the King's Confessor on his side, and they hope to gain the ear of His Majesty. But I fear me it will be all too late. If the warrant could be delayed, pardon might perchance reach in time; but as things now stand I fear to cherish hope. Let the will of God be done, my child. We must believe that He knows best."

A sudden light had flashed into Grizel's eyes, it illumined her whole face.

"Thou dost speak truth, my father," she said. "God, indeed, does know best; and let His will be done. But is it His will that one should perish whom even an earthly sovereign has pardoned, and who has never offended against Him?"

Sir John looked at her with a questioning gaze.

"God's ways, my daughter, are not as our ways, and His thoughts are past finding out. Let us brace our spirits for what may lie before us, and resign ourselves to that which He shall send. Kiss me once again, and bid me good-bye. It will not be for ever. This life is but a span, and we shall meet on the shores of eternity."

She flung her arms about his neck, and pressed her lips to his.

"Farewell, sweet father, farewell," she cried, with a little catch in her voice. "Farewell, but not good-bye. Something within me tells me that we shall meet again—in this life."

He looked into her strangely shining eyes, noted the resolute expression of her beautiful mouth, and asked almost anxiously:

"What dost thou mean, my child? What hast thou in that busy head of thine? Thou must run no risk for me; for thou art the stay and prop at home. Thou must be son, daughter, and husband—all to thy poor mother—when I am taken."

Steps were heard approaching. Grizel drew herself away, and looked once more into her father's face:

"Son and daughter—that will I be in all sooth, dear sir; but husband!—nay that will not be needed, methinks——"

"Grizel, what dost thou mean? What——"

The key was turning in the lock. She put her hands upon her father's shoulders and kissed him once again.

"Fear nothing," she said, "I am a Cochrane." And with those words on her lips she turned and left him, following her grim guide, the gaoler, till she stood outside in the street once more.

The same expression of high courage and resolve was on her face, as she pursued her way through the darkening streets, followed by the man-servant who had been awaiting her. But she did not go straight home. She turned aside up a narrow thoroughfare, and entered a house in it, with the familiarity of one who is known there intimately; and her servant had to wait long before his youthful mistress reappeared.

She went home, and went straight to her mother, who was weeping and praying in her upper chamber; there, kneeling beside the bed, Grizel told of the interview with her father, and then said in a low, earnest tone:

"Mother mine, give me thy blessing, for I must needs start forth this very night to save my father."

"Thou, child? What canst thou do?"

"Mother, I have a plan. I will not tell it thee, for it were better none should know. But pray for me whilst I am gone, that God will bless and watch over me. Methinks it was He who put the thought into my heart, and that He will speed me on my way and give me success in the carrying out of it."

"Thou wilt not run into danger, my child?" said the mother, who had come to lean upon Grizel, since her husband's captivity, almost as she would have done upon a son.

"I will not seek danger; I will avoid it where possible. But thou would'st not have me flinch, mother, when my father's life is at stake?"

"And thou must go to-night? But not alone?"

"I will take old Donald with me! And we must have the two best horses in the stable. But fear not, mother mine! In three or four days I will be back; and I trow that I shall have such news to tell, as will make thy heart sing aloud for joy."

That night, just before the gates of the city were shut, the guard saw two men riding forth together, the elder of whom he recognised as the old servant of the Cochranes. The younger of the pair, who looked like a youth, had his hat drawn somewhat close over his face. Donald gave the man a ready "Good-night," and paused a moment or two to gossip with him over the latest news from England.

"They say the next mail-bags will bring poor Sir John's death-warrant," remarked the soldier; "they must be in sore grief yonder, doubtless."

"How long does a letter take passing betwixt London and Edinburgh?" asked Donald.

"A matter of eight days each way," answered the man; and, after a few more words, Donald rode on, and joined his companion speedily.

"Eight days?" spoke a soft voice, not much like a youth's, as Donald told the news; "then, should anything go wrong with the warrant, it would be full sixteen days ere another could be got from London. Sure that would give the time—the time so sorely needed. Sixteen days!" and the words ended in a deep-drawn breath.

The old servant looked with loving eyes at the youth—who, of course, was none other than Grizel habited in the attire of a lad—a plain and inconspicuous riding suit, which she had borrowed from the brother of a dear friend, and which a little skill had altered to fit her slim figure well. Her floating locks aroused no suspicion as to her sex, in days when huge wigs adorned (or disfigured) the heads of men, and where those who could not afford these costly luxuries, and yet desired to keep in the fashion, let their own hair grow, and kept it curled and powdered. There was nothing specially womanish in the aspect of Grizel's abundant, curly hair flowing over her shoulders. She looked exactly like a smooth-faced boy, and bore herself with a bold and boyish air so soon as they were beyond the radius of the locality where her face might be known. By the time that the pair rode into the city of Berwick-upon-Tweed Grizel had come to feel so well at home in her part that she feared neither to converse with those about her, nor to show herself abroad in the unfamiliar habiliments of the other sex.

"Donald," she said, that night before they sought their beds, "we are in time. The mail has not yet passed through. To-morrow, bide thou here, whilst I ride to Belford, where I hear the messenger with the mails always pauses for a few hours' sleep. If he come hither with his mail-bags undisturbed, use thou thy wits, and seek to accomplish that in which I shall then have failed; but if he should bring news that he has been robbed, then set spurs to thy horse, and meet me at the house that I did point out to you as we rode into the town; and bring without fail the bag containing mine own attire and saddle: for then I must no longer travel as I do now."