Brenda's Cousin at Radcliffe: A Story for Girls

Helen Leah Reed

Copyright, 1902,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved.

Published October, 1902

UNIVERSITY PRESS · JOHN WILSON AND SON · CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

TO

MRS. LOUIS AGASSIZ,

THE HONORED FIRST PRESIDENT OF RADCLIFFE COLLEGE,

WHO HAS HAD NO SUCCESSOR IN OFFICE, AND

WHO CAN HAVE NO SUCCESSOR

IN THE AFFECTION OF RADCLIFFE GRADUATES

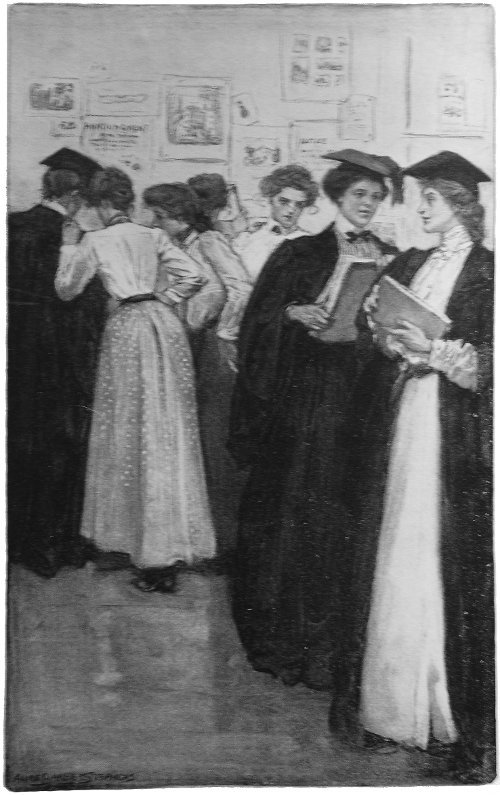

“One morning half a dozen girls clustered before the bulletin board”

Brenda’s Cousin at Radcliffe

A Story for Girls

BY

HELEN LEAH REED

Author of “Brenda, Her School and Her Club”

“Brenda’s Summer at Rockley,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY ALICE BARBER STEPHENS

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1903

That the young girls for whom it is written may see in “Brenda’s Cousin” a clear picture of Radcliffe College undergraduate life is the sincere wish of the author, who hopes also that her fellow-graduates may overlook the one or two slight anachronisms necessary to a contemporary picture.

CONTENTS

- Chapter Page

- I. New Acquaintances 1

- II. The Freshman Reception 12

- III. The First “Idler” 22

- IV. Pamela’s Perseverance 29

- V. College Callers 38

- VI. Setting to Work 47

- VII. All Kinds of Girls 56

- VIII. The Mid-years 66

- IX. Two Catastrophes 76

- X. Discussions and Discussions 90

- XI. Efforts to Help 100

- XII. Harvard Class Day 115

- XIII. Various Ambitions 130

- XIV. In Disguise 143

- XV. Angelina 157

- XVI. Who Wrote It? 168

- XVII. A Private Detective 180

- XVIII. Work and Play 189

- XIX. The Operetta 201

- XX. Juniors 211

- XXI. A Fortunate Accident 222

- XXII. Annabel and Clarissa 233

- XXIII. Clouds Cleared Away 243

- XXIV. Seniors All 255

- XXV. A Strange Meeting 268

- XXVI. The House Party 280

- XXVII. Nearing Class Day 293

- XXVIII. Commencement—and the End 311

ILLUSTRATIONS

From Drawings by Alice Barber Stephens

- “One morning half a dozen girls clustered before the bulletin board” Frontispiece

- “‘An American girl’—she spoke with emphasis—‘is her own best chaperon’” Page 85

- “Clarissa moved about the room, explaining” ″ 174

- “Lois made the bandage and put it on with a professional air” ″ 225

- “‘Julia,’ said Ruth the next morning, as the two sat in the conversation room” ″ 274

BRENDA’S COUSIN AT RADCLIFFE

I

NEW ACQUAINTANCES

A drop of ink splashed on the cover of Julia Bourne’s blue-book.

“Oh, I beg your pardon, I wasn’t thinking,” murmured an apologetic voice, as Julia glanced up in surprise. A small, pale girl standing beside her desk had evidently held her fountain pen point down with disastrous result.

“Oh, it did no great harm,” responded Julia, dexterously applying her blotter. Like the other girl, she spoke in an undertone, for silence was still the rule of the room.

“I’m thankful, however, that my book was closed,” she said to herself, as the other passed on. “A blot on an inner page might prejudice the examiner, and I shall need all his good-will.”

It was the Tuesday before the opening of college, and examinations were going on to enable some students to take off conditions imposed by the June finals, or to permit others—like Julia—to anticipate some study of the Freshman year.

Before handing in her book Julia corrected some errors, for there still lacked ten minutes of the close of the examination hour. As she sat there reading the printed questions, one by one, she was thankful for the cool day. How insufferably hot had been those two Junes when she had taken her preliminaries and her finals! Old Fay House then had swarmed with girls, lively, solemn, silent, chattering, short, tall, thin, stout, dowdy, attractive,—but why enumerate? They were as varied in aspect, and probably in disposition, as those other girls who never think of college. In comparison with the spring crowds, the girls to-day were but a handful.

Julia, glancing toward the window, caught a glimpse of the yellowing elms of Garden Street, and a soft September breeze blew across her cheek. Then her eye wandered to the photograph over the old-fashioned mantle-piece, and she thought that the class-room, except for its chairs and desks, was like the sitting-room of a private house.

Julia handed in her book promptly, but some of the others gave theirs up reluctantly, as if to say, “Oh, for ten minutes more, or even five minutes. It would make all the difference in the world to me.” One of these girls, who was tall and strong-looking, with short, curling hair, expressed her feelings emphatically.

“I don’t see,” she said, as Julia and she left the room together, “how you got through so soon. You haven’t been writing for ten minutes. Why, if we had five hours instead of two, I should still need an hour more. Weren’t you frightened to death at the preliminaries?”

“I barely survived,” replied Julia, entering into the other’s mood. “There’s an art in taking examinations that I’m only beginning to learn.”

“Well, the worst is over! Harvard, they say (and of course it’s the same with Radcliffe), is the hardest college to enter and the easiest to graduate from. That’s why I left my happy Western home. I don’t mind struggling to get in, but I want an easy time after I’ve once entered college.”

“You’re from the West?” queried Julia.

“Oh, yes, from ‘the wild and woolly West’ as you call it here. I took my preliminaries in Chicago, although my home’s farther off. Our colleges are just as good as any East, at least Pa says so. But I said ‘the best isn’t too good for me, and if Harvard’s the best of all for men, why Radcliffe must be the best for women.’ As soon as I’d thought it out I made up my mind to come here. I couldn’t have done better, could I?”

“Why, Radcliffe has a pretty good standing in this part of the world.”

“You don’t speak with enthusiasm.”

“Oh, I was only thinking that a good education can be obtained in a Western college. I’ve lived in the West myself,” she explained.

“Let me embrace you,” cried the Western girl, impulsively, fortunately without suiting the action to the word.

“You see it makes me tired the way people here pretend not to know anything about the West; but I honestly believe that you realize where Kansas is, and that St. Louis and Chicago are a few miles apart, and that the Mississippi is east of the Rocky Mountains.”

“Oh, you could probably give me points in Western geography.”

“Perhaps, but let me introduce myself. My name is Clarissa Herter, and my home is Kansas. My age is a little more than it ought to be—for a Freshman—for I’ve wasted a year at college elsewhere.”

Julia smiled at this frank inventory, and she felt that she could do no less than tell Clarissa something about herself.

“So you’re an orphan!” cried Clarissa, “and you’ve lived with relatives for two years or more. Well, you must have had a pretty good disposition to stand all the wear and tear. There’s nothing so hard as living with relatives—except one’s parents. As to your personal appearance, it suits me right down to the ground—don’t look at your boots,” she added. “I include them in the list.”

Just then a proctor approaching introduced to the two the timid girl who had blotted Julia’s book.

“I asked for the introduction,” said the newcomer, whose name was Northcote, “because I wished to apologize for my carelessness.”

“Now, really,” responded Julia, “the blot did no harm.”

“But if it had gone through the cover?”

“Oh, that would have been nothing.”

“But I fear that I did more mischief than you think. There’s a little ink spot on the side breadth of your skirt, and I’m sure that it came from my pen.”

“Oh,” cried Julia, looking where Pamela pointed, “that spot may have come from my own pen; and besides, the gown has seen its best days.”

“Well, I’m very sorry,” continued Miss Northcote.

In the meantime Clarissa had risen from the low, red couch, on which they had been sitting. “You must be a New Englander.”

“I’m from Vermont.”

“I thought so,” cried Clarissa. “You have a well-developed conscience. You seem to be apologizing for something that perhaps you didn’t do.”

“Let us go upstairs to the library,” interposed Julia, noticing that Miss Northcote was made uncomfortable by Clarissa’s badinage.

“Isn’t it pleasant! I had no idea it was so homelike!” exclaimed Julia on the threshold of the library.

“Do you mean you haven’t been here before? Why, I explored the whole building from top to bottom last June. I didn’t wait for a special invitation,” cried Clarissa.

“It was so warm then!” Julia felt almost bound to apologize.

The room that they had entered justified the term “homelike” to the fullest extent. It had none of the stiffness of a college hall, although shelves of books were everywhere, always invitingly within reach. The deep-mullioned windows, the high mantle-piece and broad fireplace all had a decided charm. From the window that Julia approached, through the elms that shaded Fay House, there was a glimpse of the Soldiers’ Monument on the Common, and nearer at hand the time-scarred Washington Elm. After looking into one or two smaller rooms filled with books, Clarissa suggested that they go into the open air.

“There must be something of the gypsy in my blood, for I begrudge every minute spent indoors at this season. Clarissa! Clarissa!” she cried dramatically, “you must out and walk.”

“Is your name Clarissa?” asked the Vermont girl.

“Why not? Doesn’t it suit me?”

“Well, it’s strange,” responded the other, “for I am called Pamela.”

“How odd! Why, people may begin to call us ‘the heroines,’ unless we show them that we’re made of stronger stuff than Richardson admired.”

“Poor Richardson! How he would be horrified to see us modern girls going to college! You must belong to sentimental families to have those names.”

“I was named for my aunt,” explained Pamela with dignity.

“Well, I’m afraid that my mother took ‘Clarissa’ from a novel,” admitted the Western girl.

After leaving Fay House, the two others walked with Julia toward Brattle Street. They had gone but a short distance when Clarissa exclaimed with surprise that it was nearly one o’clock.

“My luncheon is at half-past one,” said Julia, “but perhaps yours is earlier.”

“Yes, at my boarding-house we are very plebeian. At one o’clock we have dinner, not luncheon, while you, I dare say, have dinner at half-past six.”

“Of course,” replied Julia, while Clarissa, echoing “of course,” added, “Then you must be a regular swell. But I thought that I’d feel better to find a boarding-place in Cambridge, where their manners and customs are like ours at home.”

Not to leave Pamela out of the conversation, Julia asked her if she had found a boarding-place, and Pamela replied that she had not yet decided on a house. She might have added that all the rooms that thus far she had seen were beyond her slender purse. Before they reached Julia’s door, Pamela bade the others good-bye.

“She’s almost too good, isn’t she?” was Clarissa’s comment as Pamela disappeared in the distance.

“I like her,” returned Julia, begging the question.

“Oh, so do I; with that neat little figure, and those melancholy gray eyes, she is my very idea of a Puritan maiden. You are something like one yourself,” she concluded, “and I hope that you’ll let me call on you occasionally.”

“Why, of course, and I will call on you, too, if I may.”

Thus with the feeling that each had made a friend, the two Freshmen parted, both looking forward with interest to the college year.

Julia went to Rockley that same Tuesday afternoon, and was warmly welcomed by Brenda at the station. The younger girl, it is true, teased her cousin about being a Freshman, yet at the same time she showed so much affection, despite her teasing, that she hardly seemed the same Brenda who not long before had found in every act of Julia’s some cause for dissatisfaction.

Rockley was the summer place of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Barlow, the uncle and aunt with whom, for two years, Julia Bourne had made her home. It was on the seashore, little more than twenty miles from Boston, and Julia had passed two happy vacations there. She had gone to live with her uncle and aunt soon after her father’s death, and had completed her preparation for college at Miss Crawdon’s school, the same school that Brenda and her intimate friends attended. Brenda, Edith, Nora, and Belle were inseparables, while Julia had been more intimate with Ruth Roberts, the Roxbury girl who was now her room-mate at Cambridge.

The Barlows were to stay at Rockley until late October, and Mrs. Barlow regretted that Julia must spend that beautiful autumn month in Cambridge. She remarked at dinner that Julia looked pale, and said that she and Brenda had decided that this resulted from examinations.

“Why, you can’t imagine how weak I feel,” Brenda had added, “after an examination. You know that Miss Crawdon makes us have them, though few of us are going to college.”

“It pleases me,” Mr. Barlow had interposed, “that you and your friends should get even this indirect advantage from Radcliffe. In time the average private schoolgirl may have an equal chance with boys.”

“Why, papa, you never have wished me to go to college.”

“No, my dear, but I often have thought that you suffered at school—”

“Yes, papa, I have suffered at school, often.”

“My idea of suffering probably differs from yours. I mean that you suffer from a lack of thoroughness. Thoroughness is the first essential of college preparation.”

“Why, papa, girls can fit for college at Miss Crawdon’s. Julia and Ruth and several others prepared for the examinations. But let us change the subject,” said Brenda, adding, “What are those Radcliffe girls like? Are they very queer?”

“Why, no indeed,” replied Julia loyally. Yet even as she spoke she had a vision of Pamela and Clarissa, to whom Brenda might apply her adjective, although to each in a different way.

“After all,” interposed Mr. Barlow, “thirty-five years ago who would have imagined girls in college? Why, even twenty years ago a man would have been thought foolish to prophesy that within his lifetime girls would be admitted to full Harvard privileges.”

“Oh, but papa, it isn’t really the same as Harvard. The boys say that it is quite different.”

“Then it’s a difference without much distinction. Professor Dummer the other day told me that Harvard and Radcliffe students have identical examinations in all subjects, as well as the same courses of study. But I will grant that in athletics and that kind of thing they haven’t the same chance as Harvard boys.”

At this moment the long glass door was pushed open, and Philip stood within the room. The whole family greeted him heartily, for they had not seen him since his return from Europe. He told them that his mother and Edith had decided to stay a month longer abroad, and that he was spending a day or two on his yacht in Marblehead Harbor.

“On Thursday I must be in Cambridge, and after that the ‘Balloon’ goes out of commission for the season.”

The young people soon went out on the piazza, where they made themselves comfortable with cushions and wraps.

“It’s a great thing to be young,” said Mr. Barlow, as their laughter rippled through the open window. Two girls from a neighboring cottage had joined them, and with them was their brother, also a Harvard undergraduate. They had more in common with Brenda than with Julia, and thus the latter was free to answer Philip’s many questions about Radcliffe.

Although two or three years Julia’s senior, Philip had of late acquired the habit of turning to her for advice. To himself he admitted that her level-headedness had more than once saved him from making a fool of himself. Philip Blair had just escaped being spoiled after the fashion of most only sons with plenty of money. His parents had always been so ready to consider his wishes that he had come to think the quick gratification of his tastes a necessity. Because he was good-looking and had agreeable manners, older men and women were apt to flatter him, and his schoolmates fed his vanity in their eagerness for his friendship. Without being really weak, Philip was easily influenced; and though in school he never had been in disgrace, more than once he had been near suspension from college. A certain indolence made it hard to shake off his undesirable associates. But even the slow-thinking Edith had discovered that Philip had a real regard for Julia’s opinion.

“Mamma and I are very glad that Philip likes to talk to a sensible girl like Julia, for we were afraid that his head might be turned, with so many silly girls always running after him.” Philip’s college friends—those whom he asked to dine with him sometimes, or took to call on Edith’s friends—were afraid of Julia.

Hearing that she was fitted for college, they could not understand how Philip had the courage to talk with her, or even to dance with her. They supposed that he was polite to her simply because she was a friend of Edith’s. “Not that she isn’t a nice-looking girl, but she must be frightfully strong-minded to think of going to college.”

Knowing the Harvard sentiment toward Radcliffe, therefore, Julia was prepared for more or less teasing from Philip, and yet as she bade him good-bye she was pleased to be able to remind him that he had said hardly a thing to discourage her about her college career.

II

THE FRESHMAN RECEPTION

When Julia approached Fay House on Thursday, the opening of the term, there were girls on the steps, girls in the halls, girls besieging the Secretary’s office with questions; old students stood about discussing all kinds of things, from their summer experiences to their proposed courses of study. But the Freshmen were less often in groups. In single file they waited their turn at the office, or sat in the conversation room, catching scraps of wisdom from the lips of the older girls who passed by.

“Oh, last year I had five and a half courses, but I’ve promised papa to be more sensible and limit myself to four, so as to have some time for other things.”

This from a serious-looking girl, and then from another more frivolous, “Well, I tried to forget everything this summer, except how to have a good time. It was delightful not to have even a theme or a forensic on my mind. I was a walking encyclopedia last June, but now I feel absolutely empty-headed.”

“What in the world,” came from another group, “possessed you to take Pol. Econ. this year? I thought you were trying for honors in classics.”

“So I am,” in a rather melancholy tone; “but I’m tired of having nothing but Greek and Latin. My future bread and butter may depend on them, as I’m to be a teacher of the classics, but I’m indulging in Pol. Econ. as a luxury.”

“A luxury! Well, you’ll pay for it.”

Julia, seated at the reading table, was not only amused by these bits of conversation, but was interested in watching the passing girls.

“Isn’t it great?” cried Ruth, joining her. “It’s a little like the first day at school, and yet it’s different. Who is that queer-looking girl, she’s actually bowing to you,” with an intonation of disapproval; “why, you don’t know her, do you?”

“Yes, I met her yesterday. She’s a Freshman from the West.”

Clarissa now reached them, grasping Julia’s hand with a hearty “Well, I am glad to see you!”

“Have you chosen your electives yet?” asked Julia, after a minute or two. “Aren’t they bewildering?”

“It isn’t the elective, I’ve been told,” responded Clarissa, “but the man who gives them that makes the difference. The younger the instructor, the worse his marks. He thinks that he shows his own importance by making ‘A’ and ‘B’ marks few and far between. I’m going in for all the starred courses I can get, for then there’ll be more chance of my having real professors to teach me.”

Ruth hurried Julia away from Clarissa to an appointment with a history professor. He had wished to talk with them before consenting to their entering his class. He was pleased to find them so interested, adding, as he gave his consent:

“You must be prepared for hard work, as Freshmen are rarely permitted to take this course. I hope that you read Latin at sight, for you may have to make researches in some old books.”

Then he bowed and left them, and Ruth looked at Julia, and the latter, understanding the question that Ruth would ask, replied, “Of course I’ll help you;” while Ruth, whose Latin was weaker than Julia’s, responded, “You always were a dear.”

Julia and Ruth had arranged to board in the same house, having separate bedrooms, but sharing a large study. This was a square, corner room, with three windows. One looked down on a bit of old-fashioned garden, and the other two gave a view of some of the stately houses on Brattle Street. Their landlady, or hostess, as she liked to be called, was the widow of a Harvard instructor, who, besides a widow and two children, had left a slim little book on the Greek accusative. Mrs. Colton always had the book in plain sight on her library table, and she believed that had her husband lived he would have been one of the most distinguished of the faculty. She had long refused to open her house to Annex, or Radcliffe, students. Like many other conservative people, she did not approve of the presence of women students in Cambridge, and she did not care to encourage the new woman’s college by taking its students to board. But when the new Harvard dormitories made it harder for her to get the right kind of students to take her rooms, she began to think about the possibilities of Radcliffe. When she happened to hear that Mrs. Robert Barlow was looking for a home for her niece, she immediately sent word that she would be very glad to have her consider her rooms. She saw that it would give her house prestige to have Julia and Ruth her first Radcliffe boarders. Mrs. Barlow and the girls were well pleased with the rooms, especially as Mrs. Colton was to take no other boarders.

Ruth and Julia would hardly have been girls, however, had they been perfectly satisfied with the arrangement of the furniture as planned by Mrs. Colton and Mrs. Barlow. With the exception of a few pictures, the study was supposed to be in perfect order on that first Thursday of the term. But Julia, when they went upstairs after luncheon, decided that the divan must be moved from the windows to the corner opposite the fireplace, and Ruth suggested that the library table should go from the centre to a recess near the mantle-piece. Chairs ranged stiffly against the wall they pulled out into more inviting positions, and moved many other things. They both agreed that several pictures must be rehung, and Ruth began to jump about from mantle-piece to table to make the changes.

“Oh, do be careful!” cried Julia, as Ruth stepped from a chair to the table, with a framed Braun photograph under her arm, and a half-dozen picture nails in her hand. “Do wait,” she added, “until we can find some one.”

“Wait for whom? We can’t call the chambermaid, and Mrs. Colton would be of no more use than—well, than you, Julia. Besides, I’ve hung more pictures than you could count; and—why, what’s that?” she concluded, as a very loud knocking at the door sounded through the rooms. Forgetting the picture under her arm, as she turned she let it fall with a crash to the floor.

“Gracious!” cried Master Percival Colton, astonished at the sight of one Radcliffe girl standing on a narrow mantle-piece with another sitting on the floor picking up fragments of broken glass.

“I hope nothing’s hurt,” said Percival politely, though hardly concealing his curiosity as he handed Julia two letters. Then he turned away rather sadly, as the girls neither explained what had happened nor what they intended to do about it.

“Come down, Ruth,” cried Julia, as Percy disappeared. “Clarissa Herter, that Kansas girl, has sent her card with these letters that she found on the bulletin board. She thought that we might like to have them. Oh, they’re invitations!” she added, as she opened her envelope.

“The Senior, Junior, and Sophomore classes at home in the Auditorium, Saturday, September 30. 4 to 6.”

“Our first college invitation, and from the upper classes, too! Well, it’s evident that they don’t intend to haze us.”

Hardly had Julia and Ruth stepped into the Auditorium that Saturday afternoon when a girl with a ribbon badge greeted them warmly. From a table near the door she took two slips of paper, and, pinning one on Julia’s dress, said pleasantly, “You must excuse my being so unceremonious, but we find that this is the best way of making girls acquainted with one another, by giving them slips of paper with their names written on them. I honestly think that you feel more like talking to a girl if you know her name. Your slips are white, but we old girls wear blue.”

“But how did you know which slips of paper to give us?” asked Ruth, as she received a decoration like Julia’s.

“Oh, I was interested, that is, I asked particularly who you were the other day,” replied the older girl in a flattering tone. “But now I must find your Senior for you,” she concluded; “perhaps you haven’t met her.”

“My Senior?” asked Julia. “Why, how in the world do I happen to have one?”

“Excuse me, then, until I find her. She will tell you all about it.”

Soon Julia found herself standing before a tall, plain girl with glasses, who wore her Senior’s gown ungracefully.

“This is your Senior adviser, Miss Townall, Miss Bourne. I am sure that you will like each other;” and the vivacious usher, asking Ruth to accompany her, turned away to find Ruth’s Senior.

“Miss Darcy is always bright and cheerful,” said Miss Townall, making an effort to talk to Julia.

“Yes, indeed, I like her immensely. She’s a Sophomore, I suppose?”

“Yes, and very popular.” Jane looked at Julia, as if at an utter loss for a subject of conversation, until Julia asked her to explain the system of assigning Senior adviser. In giving information Jane waxed eloquent, and explained that the Emmanuel Society made the arrangements, bringing it about that each Senior should take charge of one Freshman, holding herself ready to give her any needed advice.

“Some of them have two,” added Ruth, who had rejoined them.

“Oh, naturally, for there are always more Freshmen than Seniors; but dear me, it’s bad enough to have one on your mind,” said Jane tactlessly.

“There, I didn’t mean that,” she apologized, at once conscious of her own awkwardness. “Of course I’m delighted to be of help to any Freshman, but there is so much danger of giving the wrong advice, and—” so Jane went on explaining and explaining, as people are apt to when once they have made a mistake, without greatly improving the state of affairs.

“But where is your Senior, Ruth?” asked Julia, to put Jane more at ease.

“Oh, I left her talking to that Western girl. She seemed so deeply interested in her that I thought I might be in the way. We have been introduced, however, and if she wishes to speak to me again, she may take the trouble to find me.”

Julia wondered if Ruth’s annoyance had come from anything said or done by Clarissa. Already she had seen that Ruth did not like the Western girl.

As the rooms began to fill with girls, Julia and Ruth recognized many whom they had seen at examination time, and among them a number from their own classes. Coffee and chocolate and sherbets were served from small tables, and the girls who served and the ushers who helped them were kept busy.

“Not sherbet, but college ice,” corrected a girl at one of the tables. “You’ll grow heartily sick of it in the next four years.”

Then Clarissa, to whom she spoke, replied, “Oh, a rose by any other name would smell as sweet; and therefore, as a Freshman I’ll ask for another glass. I suppose that our class will never again be as important as now.”

“Probably never again at Radcliffe, at least until the end of your Senior year. We take the Freshmen up tenderly, treat them very kindly on the first Saturday of the term, and then drop them suddenly. Unless a Freshman shows unusual ability, we are apt to forget all about her.”

“Then I’ll see what I can do to make myself remembered,” retorted Clarissa, as if accepting a challenge.

In the meantime Julia and Ruth had again run across Miss Darcy, and the latter had inquired if it would be an unheard-of thing for her to change her Freshman adviser.

“You can do it, of course. It has been done occasionally, but if I were you I’d wait. So few girls do make a change.”

“I fear that you think me notional.”

“Oh, no,” responded Miss Darcy. “I feel that you are going to be—that is, that you are—the typical Radcliffe girl, and that naturally means everything agreeable.”

“Yes, indeed, if we may judge by those who are here to-day.”

“Ah! we are in holiday attire now, but you will like us even at our worst.” And Julia and Ruth, looking about them, agreed that Radcliffe in holiday attire was well worth seeing. The rooms were prettily decorated, and most of the girls wore light and becoming colors. There was little formality, and each girl was not only at liberty to speak to her neighbor, but was sure to be met more than halfway.

Finally, before they separated, the Glee Club girls gathered around the grand piano, and one merry song after another was sung, to the great delight of the Freshmen. One that made the most impression was “The Only Man,” which, although unfamiliar to many of the new girls, was already counted a classic of its kind. Even Jane Townall had been known to laugh at its merry strains.

The song told of a young man who was invited to a Radcliffe tea, who, when he reached Fay House, saw only women in sight:

“The poor young man stood trembling there,

And looked about for aid,

He’d never been afraid before,

But now he was afraid.

He gave one long, last lingering look,

Then rushed out at the door.

I think that he’ll think twice before

He comes here any more-ore-ore.

“Now all you Harvard men attend!

If ever you get a bid

To a Radcliffe tea, be sure and see

If any others did.

Do you think that you could face the fate,

From which our hero ran,

Among four hundred Radcliffe girls,

To be the only man-an-an?”

There were several other stanzas, and as the hero was described as a particularly brave athlete, the refrain following each stanza was particularly entertaining, for it went somewhat in this fashion:

“He could face the Yale rush line,

He’d been captain of the nine,

He was not afraid to dine

On the new Memorial plan;

But he’d never thought to be,

At a full-fledged Radcliffe tea,

The only—only—only—only—man.”

III

THE FIRST “IDLER”

“Who’s going to the Idler?” cried Clarissa one morning to a group around the bulletin board.

Then a little Freshman spoke up timidly, “Why, can any of us go? I thought that it was a club meeting.”

“Oh, the Idler is the only unexclusive institution that I’ve struck in this part of the world. Just sign the constitution and you’re in it for life. Come, you must join; we must make our class felt.”

Pressing nearer the board, one of the group read aloud that all Radcliffe students, regular or special, were invited to a meeting of the Idler Club on Friday afternoon at half-past four in the Auditorium.

Accordingly, they were all in their places before the appointed hour. The Auditorium was overflowing, and some girls even had chairs in the aisles. Ruth and Julia leaned on the ledge of the window opening from the conversation room.

“Why don’t they begin?” asked Ruth impatiently, at quarter of five. But even as she spoke there was a lull in the conversation, and a rather commanding figure rose on the platform.

“That is the President of the Idler,” whispered Ruth, “Mary Witherspoon. I had her pointed out to me the other day.”

Miss Witherspoon made an address that was clear and to the point. She congratulated the old students on the prospect of a successful year for the Idler; she welcomed the new students very heartily, and expressed the hope that all present would at the close of the meeting enroll themselves on the Idler’s membership list. She alluded to the fact that nothing was imposed on them beyond signing the club’s very simple constitution and paying the small annual dues.

“I hope, however, that all Radcliffe girls who can do anything to entertain us, who are willing to act or sing, or even write plays, will speak with me or with some of the Idler officers on the subject. We cannot afford to let any talent lie hidden; and if a girl is too modest to let us know what she can do, some one else will be sure to tell us, and then we shall be obliged to issue some kind of a mandamus to compel her to be amusing.”

All laughed at this, and when quiet was restored Miss Witherspoon announced as the entertainment of the afternoon a farce written by two Idler members, who for the present preferred to be anonymous. Thereupon the curtain rose on a pretty stage set for a drawing-room scene. In the background were two tall plants and a bookcase and a fine water-color on an easel; in the foreground a tea-table, daintily spread, and beside it two young girls drinking tea, and discussing the advantages and disadvantages of a college education.

It was clear as the dialogue proceeded why the authors wished to be anonymous; for there were many local hits, and the applause showed that the audience recognized the college types depicted. The college partisan also created much amusement by describing the homeless creature constantly roaming the world in search of culture.

Julia and Ruth, moving about after the play, saw many of the ushers of the Freshman reception. Now, as then, Elizabeth Darcy was one of the most conspicuous. The refreshments served were very simple,—a punch bowl filled with lemonade stood on a table in the conversation room, surrounded by plates of cakes.

Ruth was soon seized by some of her own special friends, and Julia wandered over toward the Garden Street windows. She probably would not have noticed the girl sitting in a corner behind the periodical case had not a nervous voice exclaimed, “Oh, I am so glad to see you!”

As she recognized Pamela, Julia felt a pang of conscience. Absorbed in her own affairs, she had hardly remembered the Vermont girl. Now she greeted her most cordially, and as Pamela came out of her corner she saw that her face as well as her clothes had a dejected expression. Her dull-brown hair was brushed back tightly, her linen collar was fastened with an old-fashioned brooch. There was no useless furbelow about her non-descript grayish gown, and she wore an expression to match her attire.

But Pamela brightened as Julia held her hand. “Oh, I’m so glad to see you,” she repeated; “I have been very lonely.”

“Lonely! with all these girls about you?” and Julia glanced toward the girls swarming over the lemonade table, and toward the hall where there were still girls, and girls, and girls.

“I’m lonely because there are so many girls here,” responded Pamela. “I know so few, and every one else seems to have a special friend.”

Again Julia felt that twinge of conscience. She herself had not been altogether guiltless.

“Why, I am your friend, and I’m going to call on you at once, and you must come to see us some Monday soon. We are to be at home Mondays after four.”

This cordial invitation was cordially accepted, but Julia noticed that Pamela did not give her own address.

“You know every one,” the latter exclaimed, as she and Julia walked toward the Auditorium.

“Well, between us Ruth and I have met most of our class. But you ought to know them, too.”

“Oh, I never dare speak first to a girl.”

“But you ought not to feel timid in the presence of mere Freshmen, like yourself or myself.”

“I never can make up my mind to speak to them. I don’t see how I ever dared speak to you.”

“A drop of ink, don’t you remember? That did it”

“Oh, of course it was my duty to apologize.”

“Well, then, just spill a glass of lemonade over one or two of those pretty gowns, and you’ll be justified in speaking to the wearers of them.”

Though Pamela wondered if Julia was quizzing her she was not offended. Julia, realizing that Pamela was more serious than most Freshmen, thought that she might enjoy meeting some of the older and more studious girls. Looking around to see whom among them she could introduce to her, she quickly saw Elizabeth Darcy. But Elizabeth was a conscientious usher, and as soon as she had attended to the wants of one girl she flew toward another. Her eye fell on Julia just when the latter, after following her across the room, had half despaired of a chance to speak to her.

“Good afternoon, Miss Bourne,” she said, holding out her hand. “Won’t you let me get you something, lemonade or chocolate?”

“Oh, thank you,” responded Julia, “but I wish to ask a favor. May I not introduce you to a Freshman who has not many friends? She is near the door.”

Elizabeth glanced toward Pamela, standing in a limp and uninteresting attitude. Her quick eye undoubtedly noted every detail of clothes that showed unmistakably the stamp of the country dressmaker.

Elizabeth smiled sweetly, as she would have smiled under even more trying circumstances.

“I am ever so sorry, but I am frightfully busy this afternoon. Some other time, Miss Bourne, but now I could not give a minute to your—your friend; and besides, I haven’t time for any new girl unless I should happen to take a very great fancy to her as I have to you.”

In spite of the touch of this flattery, Julia justly felt annoyed with Elizabeth. “After all,” she reflected, “ushers ought to make themselves as agreeable as possible to all Freshmen, and it isn’t quite right for one of them to decline an introduction.”

Elizabeth had hastened off with polite excuses, and Julia saw her join a group of lively girls at the other side of the room. “She is not working very hard now,” she thought, moving toward Pamela. She had gone only a few steps when a rather shrill voice called her by name. Turning, she recognized a bright little Southerner who sat near her in English.

“Where are you bound? You look like you had something on your mind,” cried the Southerner, whose name, Julia vaguely remembered, was Porson.

“Why, I have a fellow Freshman on my hands; she knows hardly any one, and I would like to introduce her, and—”

“Well, I am at your service if you think that I will fill in the blank. You know this is my second year, though my first as a Freshman, and I always like to meet new girls.”

“Why, thank you,” responded Julia, “I should be delighted. She is in English ‘A,’ too, so you will have one bond of interest with her.”

Pamela was still standing where Julia had left her, but as the two girls approached she held out her hand with a “Good-bye” to Julia.

“I must go now, it is past five o’clock,” she said.

“But that is early,” responded Julia. “I wish that you could stay longer, for I have brought Miss Porson to meet you. She is in our English class.”

But even after the introduction Pamela would not linger.

“I really must go,” she said nervously. “It is past five o’clock.”

“Why, you speak like Cinderella,” cried Miss Porson gaily; “she had to go home at some unheard-of early hour—or was it a late hour? At any rate, nobody ought to be a slave to time.”

The little Southerner with her allusion to Cinderella did not know how nearly she hit the truth. But Pamela, unduly sensitive, winced at the comparison. After bidding the two good-bye, she hastened up North Avenue toward Miss Batson’s.

“Isn’t she a little—just a little odd?” inquired Miss Porson, after Pamela had gone away.

“I cannot say,” responded Julia, “I know her so slightly. I ran across her a day or two before college opened, and in some way I feel drawn toward her, although I have seen little of her.”

IV

PAMELA’S PERSEVERANCE

When Pamela Northcote first found herself in Cambridge it seemed, as the children say, “too good to be true.” It had long been her dream to study some day under Harvard professors, but in this world dreams so seldom are realized that she was genuinely surprised that her dream had come to pass. Yet Pamela herself had been her own fairy godmother, and to her own efforts she owed her appearance at Radcliffe.

Pamela had been but a little girl when women first began to study at Cambridge. Even then she made up her mind that if she could she would sometime be an Annex student. The road had been a hard one, but here she was. “It’s worth all I’ve been through to come here, worth it all.” Yet she sighed, thinking of her difficulties in getting enough money to warrant her entering Radcliffe.

Pamela had been early left an orphan, and an uncle and aunt had given her a home, if not grudgingly, at least not always cheerfully. They did what they could for her physical comfort, but they would not encourage her in her desire to go to college; and had they been willing to encourage her, they could not have helped her. They had no money to spare for superfluous things, and a college education—at least for a woman—was certainly a superfluity.

That she should go to college had seemed to Pamela a filial duty. Her father, whom she remembered but dimly, had worked his way through a small New England college and later through the Harvard Divinity School. In a trunk of old letters Pamela had found one of her father’s written to her mother when Pamela was a baby. “If our boy had lived I should count no sacrifice too great that would enable me to send him to college.” A diary of her father’s in the same trunk showed Pamela how prayerfully he had dedicated his baby boy to the ministry. But the boy had lived only a year, and Pamela knew that he felt this loss keenly. “If my father had lived he would have wished me to go to college; he would have had me study with him until I was ready. It is my duty to make the most of myself, to be as nearly as I can like what his son might have been.” So Pamela worked and struggled to get a little money together for her college education. Although her desire for a Harvard course seemed presumptuous, Cambridge was her goal. There was a good academy in the town where she lived, and this simplified her preparation. In the vacations she taught a country school, and she decided that when she had three hundred dollars she would venture it all on a year at Cambridge,—provided, of course, that she could pass the examinations. Now it happened that the very year in which she was to be graduated from the academy, a prize was offered by a rich townswoman to be awarded to the student, boy or girl, in the Classical Department who should pass the best examination. Pamela wore herself almost to a shadow studying. She won the prize, a scholarship of two hundred dollars, given on the condition that the winner should spend the money on a college course. Colleges were recommended to Pamela in which this sum would have paid almost the whole cost of tuition and board, but the young girl would have none of these. She saw in the winning of the prize a dispensation that she was to attain her long-cherished hope of going to Cambridge. She passed most of her entrance examinations that spring, drawing somewhat on her slender capital for the journey to Boston, and in September she passed the remainder. On entering Radcliffe, therefore, her assets consisted of three honors from the examinations and three hundred dollars in money. Two-thirds of this money was the academy prize and one-third was her savings of several years. The brain that she had inherited from her father and the courage that had come to her from her mother were not backed by great physical strength. She was stronger, however, than she looked, and she did not fear her course at Radcliffe.

Yet Radcliffe does not offer unalloyed bliss even to a girl as earnest as Pamela, if she has to cogitate too long on the best way of making both ends meet. Out of her three hundred dollars Pamela knew that she must spend two hundred dollars for tuition, and she wondered how she was to make one hundred dollars cover board, lodgings, and incidentals for the year. She made no account of clothes, as she did not intend to add to her slender wardrobe for another twelve months. Half of her tuition would not be due until February, and if worse came to worse she thought that she might draw on her tuition money for her board of the first half-year. Yet this was a resource only if everything else failed. She felt that if she could carry herself through the first half-year, some way of earning the money to make up the deficit would present itself in the second half-year.

The day before college opened Pamela went to see an elderly woman who had been a friend of her mother’s who kept a small millinery shop in one of the northern suburbs of Boston.

“I admire your spirit,” said Mrs. Dorkins when Pamela had described her efforts to find a cheap boarding-place. “I knew you’d have a hard time to find a place you could afford; and if you won’t be offended, I’ll tell you how you might be comfortable without its costing you much.”

“Why should I be offended, Mrs. Dorkins? I know that you wouldn’t propose anything that wasn’t right.”

“Well, a thing may be right without being exactly what you’d like. I can’t forget that your father was my minister; and when I remember what a good man he was it seems’s if you ought to have everything you want and not humble yourself.”

“But you haven’t told me, Mrs. Dorkins, what it is that you have in mind.”

“Well, a cousin of my late husband’s lives in North Cambridge; she takes young women lodgers, who get their breakfast with her and their tea. They have dinner in the City in the middle of the day, for they are all of them employed—bookkeepers, or sales-ladies, or something of that kind. There’s only four or five and they’re real nice girls, and steady pay, though they can’t afford big prices. Now she wants some one to help her with her work—my cousin does. Not a regular servant, for she does the cooking and hard work herself. But she’d like some one to set the table and wait on them morning and evening a little. She said that if she could get some one that didn’t want much pay, she’d give them a good home, and they could have all the day to themselves and most of the evenings. Now Pamela, if you was willing to do this you wouldn’t have to pay board and—”

Pamela’s heart beat violently while Mrs. Dorkins talked. This was just the kind of thing she wanted. Her subconsciousness immediately set down as wrong the feeling of pride which at first threatened to stand in the way of her accepting it.

“Oh, Mrs. Dorkins, you are very kind; that is really the kind of thing I have been looking for, only—only—”

“Yes, I know just how you feel, Pamela, but remember what Holy Writ says about pride. Not that I don’t think you’ve a right to feel as you do. Your father was a perfect gentleman, though he never had much money, and was born at Bearfield where I was born, too.”

“Oh, it really isn’t that, Mrs. Dorkins, it really isn’t pride,” and Pamela meant what she said. “Only—”

“Well, then,” said the practical Mrs. Dorkins, “I’ll go over to Cambridge to-morrow and take you to Miss Batson’s. I’m sure you’ll suit, and I hope that you’ll like her. She has a neat little place, and she’ll treat you well.”

It happened, therefore, that on the very day after the opening of college Pamela found herself moving her possessions to Miss Batson’s French-roof cottage. She was to do certain work in consideration of room and board, and she was to have a fair amount of time to herself. Miss Batson did not offer her, nor did she desire, any money payment for her services. Indeed, she considered herself almost rich. She had room and board provided for her for the year, and after paying her tuition fees of two hundred dollars she would have one hundred dollars left for books, clothes, and incidentals. This to her seemed a very large sum.

Yet there was one thing that troubled her. She would have liked a room to herself, and she found it hard instead to regard as a bedroom the sofa-bed in Miss Batson’s little plush-trimmed parlor. But in a few days she became fairly contented with this arrangement, and toward nine o’clock each evening would close the folding-doors so that she might go to bed without disturbing Miss Batson’s boarders, who often entertained visitors in the little front room.

For her study she had a corner of the dining-room table; and though her work was often interrupted by questions and comments from Miss Batson, who would look in upon her occasionally, she still reflected that she might have been much worse off. Yet sometimes she sincerely pitied herself. “It isn’t exactly pleasant to be living in a house without a single corner that I can call my own. I can never invite any one here to see me. For although Miss Batson is very kind, I know that she regards me as ‘help,’ a refined species of ‘help’ to be sure, but still only ‘help.’”

She had felt strongly drawn to Julia Bourne, and she hoped that she might be able to see much more of her. Yet she reddened as she thought of Julia in much the same way that she reddened whenever the subject of her boarding-place came up. Although she was a minister’s daughter, although she realized the sin as well as the folly of false pride, she yet felt uncomfortable whenever she reflected that to the unprejudiced observer, indeed to any one except Mrs. Dorkins, she might seem to be only Miss Batson’s “help.”

Miss Batson’s boarders could not understand her. They were young women who earned fairly good pay, as expert bookkeepers or clerks. They knew that Pamela was a student, and one or two of them were sorry that so delicate a looking girl should be obliged both to work and to study.

“It isn’t that the work is so hard,” said the youngest of the bookkeepers, “but to think of a little thing like her studying those great books. I’ve noticed her coming in in the evenings, and she’s always loaded down with books. Anybody’d have to wear glasses if they spent all their time looking into books. I wouldn’t do it myself. Why, it must be most as hard as school teaching, and I always thought that that was dreadful.” Yet Miss Batson’s young ladies (for in this way did their landlady always speak of them) in spite of these occasional criticisms were proud to have a college student living in the house. They were inclined to be very friendly, and Pamela sometimes reproached herself for keeping them at a distance. Their well-meant familiarities annoyed her, and she found it hard to conceal her feeling. In consequence she was much lonelier at Miss Batson’s than she need have been.

It was rather an understanding than an arrangement that she should be at home in the afternoon in time to help Miss Batson prepare her half-past six tea. This meant that Pamela should be at home by half-past five; and as she always walked home from the Square, she had to leave Fay House by five o’clock. There was really no hardship in this, since all recitations were over by half-past four. On the other hand, Pamela had decided that to do her duty by Miss Batson she ought to refrain from any part in the social life of the college, for she had learned that nearly all the clubs and receptions were held between half-past four o’clock and six.

It was on this account that she had given up the Freshman reception. In spite of her Spartan resolve, Pamela had just a little longing for the fun that certainly formed a legitimate part of college life. Although she had had more than her share of care, although of a more serious temperament than many of her classmates, she was still girl enough to see the possibility that Radcliffe offered for social enjoyment. Yet with this perception came a sense of her own lack of adaptability to people; instead of attracting them, she felt that she rather repelled those whom she met.

V

COLLEGE CALLERS

One afternoon as Julia and Ruth were walking toward Elmwood a human whirlwind stormed past them, composed, as it seemed, chiefly of woollen sweaters and legs in knee breeches.

“There,” said Ruth, “what geese boys can make of themselves! Actually, I think that I recognized Philip among them.”

“Yes, I believe he’s in training.”

“Well, I’m glad that he has something to do. But I wonder that he and Will haven’t called on us.”

“Seeing us may remind them. I know that they have been intending to call.”

Julia’s surmise proved correct, and that very evening the cards of the two Seniors were brought to them. When Julia and Ruth went downstairs to see them, Philip said in half apology:

“We’ve often wandered in this direction in our evening strolls, but we have never had the courage to come in.”

“What in the world made you so courageous tonight?”

“Well, you see,” said Will, “Philip came back to the club after dinner with glowing accounts of you both. He said that he could not see that you had changed a hair since coming to Radcliffe.”

“What in the name of common sense did he expect?” Ruth’s voice had a note of indignation.

“Why, we expected a great alteration. In the first place, to be typical Radcliffe girls you ought to wear glasses. Then I am sure that you ought to have had a huge bundle of books under your arm, and your clothes—it gets on my nerves to see the clothes most of the Cambridge girls wear; I suppose they are Radcliffe girls. But I could see that you looked as up-to-date as Edith.”

Philip, almost out of breath with the exertion of explaining himself, was disconcerted by the laughter that greeted his words.

“It is greatly to be feared,” said Ruth, “that the typical Radcliffe girl would be as hard to find as the average Harvard student. I haven’t seen either of them yet. But it’s really too funny for you to have expected Julia and me to develop our college peculiarities so soon. Give us time and we may become typical.”

“Ah, well, of course now,” said Philip, “I did not expect to find you entirely changed, although you know yourself that college might make a difference.”

“Naturally we’d rather not belong to the tiresome class of persons who are always the same, yet we do not wish our friends to find us altered.”

“No, you were well enough before,” and Will glanced toward Ruth.

“So you thought it best to let well enough alone?”

“Now, really you are severe! But not to dwell on personalities—how do you like your rooms here? They seem very domestic.”

“These are not our special rooms,” explained Julia; “our study is upstairs.”

“When are we to see your study, or ‘den,’ as I suppose you will come to call it?”

“I’m afraid that you would not think it typical enough to be called a den.”

“But when are we to see it?”

“Oh, later we’ll give you a tea, with Aunt Anna or Mrs. Blair to chaperon us. You’ll have a chance then to offer any amount of advice.”

“We’ll give you points that may be useful next year.”

“Ah! next year we’ll be Sophomores, and Sophomores know everything,” retorted Julia.

“Yes, and sometimes more than everything. We did, didn’t we, Philip?”

“I should say so! I’ve never since been so wise as I was in that Sophomore year. I’d almost like to be a Sophomore again.”

“You may have the chance,” interposed Will, “if you drop down a class at a time.”

Philip looked uncomfortable.

“Be careful, please; no twitting on facts.”

“On facts?” queried Ruth. “Is it as bad as that?”

“Oh, the Faculty has a wretched habit of giving a fellow warnings, especially at the beginning of the Senior year, just to see how he will take them.”

“Why,” said Julia, “I should take them as warnings.”

She saw by Philip’s expression that there was more than a mere suggestion of truth in what Will had said, and she resolved at the first favorable opportunity to have a serious talk with him. She remembered that the preceding year he had spoken of one or two conditions to be worked off before the close of his Senior year, and she began to fear that he had neglected to do this. In spite of his little affectations, Philip had a charm for Julia. At least she felt a genuine interest in him, partly on his own account, and partly because she was so fond of Edith. She hoped that he would make more of himself than some of the young men in his set had thought it worth while to make of themselves.

While her thoughts were wandering, the conversation of the other three went straight on.

“If we only knew what you would like,” Philip was saying, “we might give you something more substantial than points for your room. I have a fine ‘To Let’ sign that was hung out originally somewhere down in the ‘Port.’ I haven’t really room for it, and—”

“Oh, that’s only black and white. When you make a present, you ought not to be mean,” said Will. “What’s the matter with that barber’s pole that you cherish so carefully in a corner of your room? I hear that its former owner is still searching for it. A Radcliffe room would really be a safer retreat for it than yours.”

“Oh, no, I wouldn’t get these girls into trouble. If I present them with anything it must be something ennobling,—a tidy, or—or—a picture-scarf, or something of that kind.”

“We haven’t a tidy in our room,” interposed Ruth triumphantly.

“Then it must have a very unfeminine appearance,” responded Philip. “I am sorry that Radcliffe influences are so hardening. It wasn’t that way when you helped in that Bazaar. Don’t you remember what work I had to find something suitable for a college room, and there was nothing to be had but tidies, and dolls, and things like that? Your minds were all feminine enough then.”

“I remember that I found just what I wanted,” said Will, smiling at Ruth. “A very beautiful sofa pillow, with a crimson ‘H’ embroidered upon it.”

As it was Ruth who had made this pillow for the Bazaar given by the Four Club, and as Will had insisted on buying it as soon as he learned that it was the work of her hands, she naturally looked conscious at this reminiscence.

Thus the conversation of the four young people flowed on; and although the girls tried not to be too serious, they really did glean some useful information from the two Seniors. The gossip of undergraduates about professors, their fancied insight into the methods of their instructors is harmless enough. Yet critical listeners might have questioned the correctness of some of the judgments so glibly put forth by Philip and Will.

Philip, to tell the truth, was surprised to find himself encouraging the girls in their college career by even these scraps of information. He liked Julia so well that he could not reconcile himself to her going to college.

“It is different,” he had said to her magnificently one day at Brenda’s, “it is different, of course, in the case of a man. If he doesn’t go to college he doesn’t amount to much. People think it’s because he can’t get in, and that kind of thing. But for a girl, why you know that it really hurts her in the opinion of most people if she goes to college.”

Like his sister Edith, Philip was occasionally rather tactless, although both had the best intentions in the world.

“I hope that I won’t be hurt, at least in the opinion of my friends, by going to college,” said Julia quietly.

“Of course not,” rejoined Philip. “I might feel that way about some other girl, but not about you.”

Julia accepted the apology, but she remembered the incident. She thought of it again, as she sat before her fire that evening, and then her thoughts travelled toward Brenda. Brenda, too, had never really approved of Julia’s going to college.

“It was funny, although not exactly amusing,” reflected Julia, “when she let Belle persuade her that it was an affront to the family when I wished to study anything so unconventional—for a girl—as Greek. Yet all’s well that ends well, and Brenda is so different now that I can hardly believe that it is only two years since she was so pettish and inconsiderate.”

Yet although Brenda had certainly improved in the past two years she was still as far from perfection as most young girls of sixteen or seventeen. She was still impulsive, and disinclined to receive advice. But remembering her past mistakes, she was less ready than formerly to find fault with Julia.

One thing that had brought the two girls together was a common interest in a poor Portuguese family. The helpless Rosas living at the North End had appealed very strongly to Julia, and for a time she had feared that she might not be able to do much for them, because Brenda and her three most intimate friends had undertaken to make the mother and children their especial protégés. At length Julia’s opportunity had come, and she had not only shared in the Bazaar by which “The Four” had raised money for Mrs. Rosa, but she had also assisted in moving the family from the North End to a healthier home in the pretty village of Shiloh.

Since then the Rosas had apparently prospered, and Julia could think of them with satisfaction. Her interest in them had a double thread, for besides sympathizing with their helplessness, she felt that but for the Rosas, and the events connected with their removal to Shiloh, she could hardly have had so complete an understanding with Brenda.

Yet in her heart Julia realized that as they grew older she and Brenda were likely to see less rather than more of each other, their tastes were so very different. Brenda had still a year more of school before her, and when that was completed she would enter society. For a few years life would be a whirl of pleasure, and she would give comparatively little time to serious things. She was bound to be a butterfly of fashion, though her father and mother would have encouraged her had she wished to take life more seriously. On the other hand, they would have been glad had Julia, their niece, shown some interest in other things besides her studies.

“I do care for other things,” said Julia to herself, as she sat before the fire this evening. “I do care for other things, though it is hard to make Aunt Anna and Uncle Robert believe that I am not entirely bound up in my studies. I really believe that I should enjoy a year of society almost as much as Brenda. But the trouble is, I might grow to care for it too much. I love study, too, and I should be afraid that if I were to put aside my plans for college, even for a single year, I might in the end regard college work as a task, and wake up too late to find society all hollow. No, it is better as it is, although Aunt Anna feels that she has failed in her duty to me, because she cannot introduce me formally to society.”

To some girls situated as Julia was, the line of work that she had laid out would have been hard to follow; for although not a great heiress, she had inherited fortune enough to make her perfectly independent. Her purpose in going to college was not to fit herself to earn her living.

“I should like to feel that I could earn my own living if I should ever lose my money. It is not pleasant to feel that one is only a consumer, a cumberer of the ground, and not a helper.”

Now Julia had already discovered that not all the girls in college were there to carry out the loftiest aims. Some were as evidently bent on enjoying themselves as the girls of Brenda’s set. Even thus early in her Freshman year Julia had noted the difference between the two classes, the workers and the shirkers. Of course, in her short time at Radcliffe, she had not attempted to put all her acquaintances into one or the other of these classes. But she had already seen considerable difference in the methods of her classmates. Some sat dreamily, even idly, through a lecture, making only occasional notes. Others hung on the words of their instructor, writing pages and seeming fearful of losing a word.

Some took down the names of any books the instructor named as useful for further reference. Others seemed absolutely indifferent to everything of this kind.

Julia was not really a severe critic, and she made allowances. “I must not forget to tell Brenda that there are, at least, two or three girls at Radcliffe who really enjoy frivolity.”

VI

SETTING TO WORK

Pamela never for a moment felt any lack of liberty in Cambridge, in spite of the fact that she had less of real leisure than most of her classmates. Her life at Radcliffe was so much nearer her ideal than anything she had previously known that she was in a state of constant thankfulness. Clarissa, on the contrary, found the very atmosphere of the college restraining.

So few were the rules at Radcliffe that Clarissa had a breezy way of forgetting that any existed. She disregarded, for example, the notice in the catalogue that students could board only in houses approved by the Dean. She was therefore surprised when the request came that she should call at the office to explain why she had chosen a house where several Harvard men were boarding.

“What funny ideas they have here in Cambridge,” she had said when describing the interview. “Why, Archibald is my third cousin, and we grew up together. My mother and father would just as soon have him in the same house. They’d know that he would look after me. He’s horribly serious. I wonder if the powers that be here in Cambridge ever heard of co-education?”

“Oh, the rule is intended for the greatest good of the greatest number,” replied Julia, to whom she had told her tale of woe. “With fascinating youths in every house where Radcliffe girls board, think of the hours that might be wasted in matching wits!”

“Fascinating!” responded Clarissa disdainfully; “there’s little chance that I would waste time over them. Of course Archibald offered to move, but there were two other Freshman youths in the house, and so I had to go. My present abode is most domestic with ‘Home, sweet home’ worked in worsted on the walls, and a plush-covered album and two Radcliffe students as the chief adornments of the parlor. That ought to suit you, Julia—oh, I beg your pardon, Miss Bourne.”

“Why not Julia?”

“Oh, I notice that people here are so afraid to call one another by their first names. For my part, I always think of the Christian name first. It has so much more character.”

“So few people call me ‘Julia’ that I am always pleased to add a new friend to the list.”

“Well, then, since you are so very kind,” responded Clarissa, smiling, “perhaps you’ll let me give you some suggestions about the approaching mid-years. I believe that I am on the high road to success.”

“Then do tell us,” cried Ruth, who had just entered the room.

“Well, I show a frantic interest in all the reference books mentioned, and I’ve even bought one or two of them. I also make a special note of any witticism—alleged witticism—of my instructor. Then I’m building up a scholarly reputation by adorning my room with books and plaster casts. When I have a brass tea-kettle I shall be ready for company. But it will be tiresome to keep that tea-kettle polished.”

“It’s less trouble than you might think,” said Julia, laughing. “That’s the advantage of owning a roommate.”

“Well, you are an angel. Miss Roberts, do you do all the polishing in this establishment?”

“Ah! it wouldn’t be becoming to disclose how much work I do.”

“Oh, well,” said Clarissa, “it’s a fair division of labor after all for you to do the rubbing and scrubbing, while Julia does the æsthetic and ornamental for the two.”

Ruth colored at this remark, and Julia looked up in surprise at the careless Clarissa. But the Western girl, unconscious of offence, was looking at the photographs on the mantle-piece.

Before Clarissa turned around, Ruth, gathering up her books, had left the room.

“Why did she leave us?” asked Clarissa, discovering her absence.

“Oh, she often studies in her own room. Only on Monday afternoon does she feel perfectly free.”

“I see,” responded Clarissa, “I am a little in the way to-day.”

“Not as far as I am concerned,” responded Julia. “I’ve been studying and I am glad to have a little rest.”

“A little intellectual rest,” responded Clarissa, “as the Bostonian says when he goes to New York. Well, I ought to come on Mondays, only there’s always some one else here.”

Julia was accustomed to Clarissa’s badinage, but Ruth unfortunately did not like Clarissa as well. Julia therefore regretted her ill-considered remark.

Clarissa spent much time bewailing the fact that she had to be a Freshman at Radcliffe when she had already spent a year in a Western university.

“Pa promised me,” she said, “eight hundred dollars a year for three years, and I suppose that I ought to save out of that for my fourth year. I never imagined that I should have to spend four years at Radcliffe; it’s just ridiculous to have to begin all over again. However, what can’t be cured must be endured. But Pa will always think it was my fault in some way that I didn’t get admitted a Sophomore.”

“But you’ve made it clear to him?”

“Oh, yes; but it’s hard to make any one not on the spot understand just how things are. I might get through in three years, just as some of the boys do, but I can’t make up my mind to grind. There are so many interesting things to see and do in Boston. I really can’t pin myself down to hard study. In the first place, I can’t get used to the methods. It seems as if there is nothing to do but listen to lectures and take notes. I’m only beginning to understand how to take notes.”

“It’s a science in itself,” said Julia.

“I should say so,” continued Clarissa. “I shouldn’t like to have any one see what a hodge-podge I made of my note-books the first three or four weeks. I couldn’t make head nor tail of them until I had borrowed the notes of one of the model girls to interpret them by.”

“It was hard for all of us,” said Julia, “at least it was for me.”

“Well, our first hour examination showed that we must remember the instructor’s words, that it wasn’t enough to imbed them in hieroglyphics. Allusions that I had considered mere ornaments I soon found ought to have been taken seriously. Little innocent references to some reserved book were of more importance than hours of lectures. Alas! alas!”

Julia smiled at her expression of sorrow.

“You need not laugh,” said Clarissa. “I had meant to do most of my reading next summer, and I had not even taken the trouble to note the names of the books referred to. But I find that having electives does not mean that you can elect to study or not, just as you please. The mid-years will be serious enough, judging by the samples we have had.”

Clarissa was not the only Freshman to find difficulty in accustoming herself to Radcliffe methods. Many others, unused to the lecture system, had rested too securely in the hope that before the mid-years they could make up all deficiencies. As the college year went on they were bound to find, like all preceding Freshmen, that lectures in the end were far more stimulating than recitations from even the best of text-books, and in the course of time, too, even the dullest was likely to acquire the art of successful note-taking.

The hour examinations at irregular intervals before Christmas were often rude awakeners for careless girls. Others were agreeably surprised to find their marks better than they had hoped.

“It’s uncertainty that kills one,” said Clarissa. “I mean to work so that my mid-years will give me ‘B,’ or at any rate ‘C’ in English. The warning, you will see, shall not have been in vain. I used to think that I knew something about Rhetoric, but it seems that I was wrong, though I studied it years ago in the High School.”

Although Clarissa’s rather original manner of expressing herself did not wholly meet the approval of her English instructor, since the first examination he had expressed a certain restrained approval of some of her written work.

In November even the shyest Freshmen had begun to find their place at Radcliffe, and to feel that they had some individuality. The classes, relatively small compared with Harvard, enabled the members of each class to know one another by sight and name, even if the acquaintance went no further. But the new girls were impressed by the fact that intimacies in no way followed class lines. The elective system made it possible in many courses for Freshmen and Seniors to sit side by side, nor did a Senior lose dignity by associating with the lower classes. Clarissa constantly commented on this evidence of a spirit so different from that to which she had been accustomed at her Western college.

Pamela accepted everything at Cambridge as a matter of course. Nothing seemed strange to her because she had expected everything to be strange. Whatever was, was right for Pamela, so far as Radcliffe and Cambridge were concerned, and she lacked Clarissa’s bubbling energy, which constantly sought some object to reform.

“I can’t say that I disapprove of the present state of things, though I really cannot understand it. Here we are in the same town with hundreds—yes, thousands—of students, and yet we see few of them at close range, and then those we know are only our brothers or cousins or something of that kind.”

“‘Something of that kind’ is delightfully indefinite,” said Polly Porson, the little Georgian whose condescension as a Sophomore had won Julia’s gratitude at the beginning of the term. “You speak like you were disappointed,” continued Miss Porson, “but if you stop to think, it’s well that we have so little to distract us. We are not forbidden to cross the college yard if we really wish to. But only think what a nuisance if they were permitted to walk about our little campus!”

“Do you suppose that there is any rule against it?” asked Clarissa mischievously.

Polly laughed in reply. “Well, the average undergraduate would almost rather be suspended for three months than find himself within our grounds. Some of them make a virtue of not knowing just where Fay House is, and you’d be surprised to find that many explain with pride that they’ve never met a Radcliffe girl.”

“We must change all that,” cried Clarissa. “Not that we are anxious to have the acquaintance of those callow youths,—for they must be callow to look at us in that tone of voice,—but we must do something or have something here that will make them anxious to know us better.”

“We can get along very well without their society,” interposed Elspeth Gray, who happened to be passing through the conversation room where Clarissa and Polly and one or two others were talking. “We’re not exactly cloistered here in Cambridge, as girls are at some colleges. Most of us have the society, more or less, of real men, and we do not depend on undergraduates.”

“All the same,” said Clarissa, “we might have a little more fun here. Now, Polly Porson, you must admit that it’s a trifle slow here for a college town.”

“Most of us were not looking for fun when we undertook to come to Radcliffe. Cambridge never had the reputation of being very amusing. But I’ll tell you something to raise your spirits. Rumors of the charm and wit of the Idler theatricals have begun to penetrate the brick walls of Harvard, and last year we heard of sorrow in college halls because men were not admitted to the performances. What we couldn’t attain through our work we have accomplished by our play. They wouldn’t lift their hands to read one of our examination books, but they would give more than the admission fee to see us act.”

“Aren’t they permitted to come?”

“No, indeed, although we really ought to find some way of letting them reciprocate our interest in the yearly Pudding theatricals.”

“We ought to be able to get up something to interest them,” said Clarissa.

“Can you act?” asked Polly abruptly.

“Why, yes, after a fashion,” responded Clarissa.

“Well, then, do give your name to Miss Witherspoon. It isn’t the easiest thing in the world to find girls willing to do their part. But there! you must have heard the invitation given at the first meeting.”

“I heard it without taking it to myself. I’m not the person of talent for whom the Idler is looking.”

Whatever her other faults, Clarissa could not be accused of vanity.

VII

ALL KINDS OF GIRLS

Among the girls in her Latin course one had a particular charm for Julia. She was tall, slight, and graceful, with waving brown hair. Lois lived in Newton, and often for exercise she walked at least as far as Watertown after lectures. Sometimes Julia walked with her; and although Lois was not too confidential, Julia had gradually learned many things about her. She knew that Lois made her own clothes, and that home duties prevented her spending much time in Fay House frivolities.

So far as she could, Lois had elected studies that would count toward her proposed medical course. She was bright and cheerful, and always ready to help others.

“She is certainly very clever,” Ruth had said appreciatively one day after Lois had given her a suggestion as to the proper translation of a very difficult passage. Julia was glad that Ruth liked Lois so well, for she had not smiled on her friendship with Clarissa and Pamela.

Polly Porson liked Lois, too, although she was in the habit of saying that her energy tired her.

“You look as fresh as a rose!” she exclaimed one morning, as Lois, with cheeks pink from exercise, came into one of the smaller recitation rooms where two or three girls were studying together.

“Well, I ought to have a color,” said Lois. “I’ve walked over from Newton.”

“Why, Lois Forsaith,” cried Polly, and “Lois Forsaith!” echoed Ruth. “Why in the world do you walk on a day like this?”

“This is just the kind of day for a walk. I had to stay indoors yesterday because my mother was ill, and on Sundays there is so much to attend to. I hadn’t time even to go to church. But the walk to-day has set me up again, and I feel equal to anything.”

“Walking is as bad as the gym.,” cried Polly Porson; “in the South we wouldn’t think either exactly ladylike. Why, until I came North I’d never walked a mile, really I never had, just for the sake of walking, I mean.”