Irma in Italy: A Travel Story

Helen Leah Reed

IRMA IN ITALY

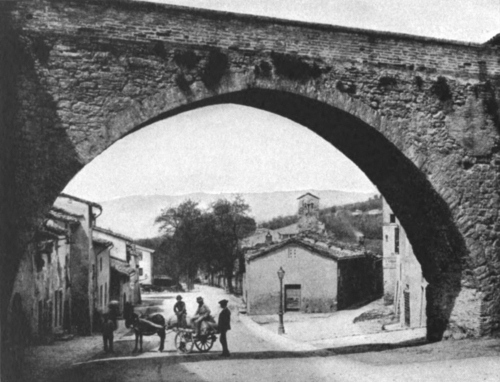

PERUGIA. Frontispiece

(See page 205.)

IRMA IN ITALY

A TRAVEL STORY

BY

HELEN LEAH REED

Author of "The Brenda Books," "Irma and Nap,"

"Napoleon's Young Neighbor," etc.

ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

AND FROM DRAWINGS BY WILLIAM A. McCULLOUGH

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1908

Copyright, 1908,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

The Tudor Press

BOSTON, U. S. A.

To M. E. F.

A TRUE TRAVELLER

CONTENTS

| PAGE | ||

| I. | The Start | 1 |

| II. | The Western Islands | 19 |

| III. | Toward the Continent | 39 |

| IV. | Away from Gibraltar | 60 |

| V. | On Shore | 80 |

| VI. | Naples and its Neighborhood | 98 |

| VII. | Cava and Beyond | 111 |

| VIII. | Paestum and Pompeii | 125 |

| IX. | Roman Days | 146 |

| X. | A Queen and Other Sights | 169 |

| XI. | Tivoli—and Hadrian's Villa | 187 |

| XII. | An Ancient Town | 203 |

| XIII. | Old Siena—and New Friends | 215 |

| XIV. | Nap—and Other Things | 232 |

| XV. | A Letter from Florence | 251 |

| XVI. | A Change in Marion | 270 |

| XVII. | In Venice | 288 |

| XVIII. | Explanations | 312 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| Perugia | Frontispiece |

| "I wish I could take them all," she said | 6 |

| Naples. A Street View | 84 |

| "With one girl clutching her dress, she could not move fast" | 132 |

| Pompeii | 144 |

| Near La Trinità, Rome | 170 |

| Rome. Group on Spanish Steps | 170 |

| Cascades at Tivoli | 188 |

| Wall of Orvieto | 188 |

| Spires of Florence | 262 |

| San Marco, Florence | 262 |

| Siena. General View with Campanile | 292 |

| Ravenna. Theodoric's Tomb | 292 |

| "As Irma approached, the girl looked up" | 296 |

| Venice. The Grand Canal | 308 |

| Venice. A Gondolier | 308 |

IRMA IN ITALY

CHAPTER I

THE START

"Of course it's great to go to Europe; any one would jump at the chance, but still——"

As the speaker, a bright-eyed girl of sixteen, paused, her companion, slightly younger, continued:

"Yes, I know what you mean—it doesn't seem just like Irma to go away before school closes. Why, if she misses the finals, she may have to drop from the class next year."

"Probably she expects Italy to help her in her history and Latin."

"Travelling is all very well," responded the other, "but there's nothing better than regular study. Why, here's Irma coming," she concluded hastily; "she can speak for herself."

"You are surely gossiping about me," cried Irma pleasantly, as she approached her two friends seated on the front steps of Gertrude's house. "You have surely been gossiping, for you stopped talking as soon as you saw me, and Lucy looks almost guilty."

"Listeners sometimes hear good of themselves," replied Lucy, "but we'll admit we have been wondering how you made up your mind to run away from school. I shouldn't have dared."

"My father and mother decided for me, when Aunt Caroline said she must know at once. There was some one else she would invite, if I couldn't go. I simply could not give up so good a chance to see Europe. But of course I am sorry to leave school."

"Now, Irma, no crocodile tears." Gertrude pinched her friend's arm as she spoke. "Fond as I am—or ought to be—of school, I wouldn't think twice about leaving it all, if I had a chance to shorten this horrid winter."

"Winter! And here we are sitting in the open air. In six weeks it will be May, and you won't find a pleasanter month in Europe than our May," protested Lucy.

"We intend to have some fine picnics this spring; you'll lose them if you go," added Gertrude.

"One can't have everything," sighed Irma. "I know that I must lose some good things if I go away."

"Examinations, for instance," cried George Belman, who had joined the group.

"And promotions, perhaps," added John.

"But still," continued George, "I say Irma deserves a change for her unselfishness in having whooping-cough last summer, just to keep Tessie company."

"Well, it was considerate in Irma to get over it before school opened; stand up, dear, and let yourself be counted."

"Oh, Gertrude, how silly you are!" but even while protesting Irma rose slowly to her feet, and her friends, looking at her, noticed that she was paler and thinner than she had been a year earlier.

"Come, now," said Lucy, rising, and affectionately slipping her arm around Irma's waist, "tell us your plans. Gertrude knows them, but I have heard only rumors."

"I am not quite sure myself about it all. Only I am to sail with Aunt Caroline and Uncle Jim to Naples by the southern route, and, after going through Italy, we shall be home in July—and a niece of Aunt Caroline's, or rather of Uncle Jim's, is going with us."

"You didn't tell me that," interposed Gertrude. "You won't miss us half as much if you have another girl with you. I begin to be jealous."

"If there were ten other girls in our party I'd miss my friends just as much," said Irma. "Besides, I'll be too busy to take an interest in mere girls."

"Busy!" It was George who said this, with a little, mocking laugh.

"Yes, busy; busy sightseeing and reading, and perhaps studying a little. For you know I must take a special examination in September. How mortifying if I had to stay behind next year!"

"Then I shall drop behind, too, or at least I should wish to," said George gallantly.

"Did some one speak of summer?" asked Lucy, rising. "Now that the sun is low I am half frozen. Come, Irma, I will walk to your door with you," and, after a word of farewell to the others, the two friends walked away together.

Irma, now in her second year in the High School, had really enjoyed her studies, and she was sure that her ancient history was to be made much more vivid by her journey, and even the dry hours she had spent on Cæsar would count for much when she reached Italy. It was well, perhaps, that Irma herself had little to do in preparing for her journey. As it was, it was hard enough to keep her mind on lessons those last weeks, when there was so much besides to think of. Still, the March days flew by swiftly. Irma was to sail from New York the Saturday before Easter, which this year came very early. A week before she was to start a steamer trunk arrived from New York, accompanied by a letter from Aunt Caroline.

"Your mother must have so much to do that I wish to save her a little of the trouble of shopping," wrote Aunt Caroline, "and I do hope that these will fit you."

"I can't see that the steamer rug is a very close fit," said Rudolph, laughing, as Irma held up the warm-looking square of blue and green plaid. "But the Panama hat's all right,—only the rug and the hat will look rather queer together."

Into the steamer trunk during the week Irma put many little things that the girls at school—and indeed some of the boys—gave her as parting gifts.

"I wish I could take them all," she said, as she stood beside the trunk. "But there are so many duplicates. I suppose I could use two pinballs and two brush-holders, but I don't need three needlebooks and half a dozen toothbrush cases. Oh, dear, and all have been so kind that I wish they had compared notes first, so that I needn't have so many things I can't use."

"I WISH I COULD TAKE THEM ALL," SHE SAID.

"It's better to have too many than too few," said Tessie sagely. "Tessie," however, only occasionally, since the ten year old maiden scorned the diminutive of her earlier years, and insisted that now she was old enough to be known as "Theresa."

"It's better for you, Theresa," responded Irma, "for some of these things may find their way to your room. Lucy might let me give you this needlebook, or at least lend it, for perhaps it wouldn't do to give a present away."

"Well, I'll borrow it now, to help me remember you when you are gone," and Tessie, delighted with her treasure, ran off to her room with it.

During her last days at home Irma realized that Nap was not happy. He followed her from room to room, and, so far as he could, kept her always in sight. When she sat down, he lay at her feet with his nose touching her dress. When she moved she almost stumbled over him; and once, when she went to close the steamer trunk, there he was inside! He might have suffered Ginevra's fate, had not Irma happened to look within.

"He truly knows just what you are going to do, and he meant to hide until the trunk was opened on the ship, so you'd have to take him with you," cried Tessie.

"Yes," added Chris, "perhaps he thinks that's his only chance of finding Katie Grimston again. She's still in Europe, isn't she?"

"Well, Katie Grimston shall never have him."

"But she did not give him to you; she wrote she would claim him on her return."

"Yes, but she isn't here to claim him, and possession is nine points of the law." Then Irma picked the little creature up and ran away with him.

The boys were very philosophical about their sister's departure.

"If I should stay home they'd be grievously disappointed," Irma confided to Gertrude. "They are calculating so on the stamps and post cards I am to collect for them, that I wouldn't dare change my mind."

Mahala's interest, however, made up for the indifference of the boys to their sister's departure.

"We shall miss you dreadfully," and Mahala sighed heavily, "though it's a great thing for a person to have the advantage of foreign travel; not that I'd cross the ocean myself, for what with the danger of meeting icebergs," she continued cheerfully, "and bursting boilers and all the other perils of the sea—dear me, I'd feel as if I was taking my life in my hands to embark on an ocean liner. But I'm glad you're going, Irma. One of the family ought to have the experience——"

"Of icebergs and bursting boilers," cried Irma. "O Mahala, I am surprised at you."

"Going to Europe has seemed to me like a dream," continued Irma, turning to her mother, "but Mahala would change it to a nightmare," and the help from Aroostook, Maine, withdrew in confusion to the kitchen.

If Irma had thought going to Europe a dream, the dream seemed pretty nearly true one Saturday morning, when from the deck of the great steamship she watched the receding dock, until in the crowd she could barely discern the figure of her father as he stood there waving his handkerchief. At this moment there were real tears in her eyes, though she had fully made up her mind not to cry. For the moment a great many thoughts crowded upon her,—memories of her mother looking from the window as the coach drove off to the station, of the boys and Tessie standing at the gate, and Mahala on the steps with Nap in her arms, held tightly, lest his continued wriggling should at last result in his running after the carriage.

"It's really very selfish in me to go so far when none of the others can go," Irma mused, and as the ship moved seaward, she was so lost in sad thoughts that she hardly heeded Aunt Caroline's "Come, dear. Here is Marion, whom you haven't met yet."

Turning about, Irma experienced one of the greatest surprises of her life. Instead of the girl in long skirts whom she expected to see, there stood by her aunt's side a tall boy, apparently a little older than John Wall or George Belman. Who could he be? And where was Marian? The boy had pleasant, brown eyes, but a fretful line about his lips interfered with the attractiveness of his face.

There was no time for questions. Before Irma could speak, Aunt Caroline continued, "I do hope you two young people will like each other. Marion, this is Irma, about whom I have told you so much."

The boy and the girl looked at each other for a moment in silence. Irma was the first to speak.

"Why—why I thought from your letter that Marion was a girl," she said awkwardly.

This speech did not better matters. Marion was still silent as he extended his hand to meet the one that Irma offered him. Then, acknowledging the introduction with a touch of his hat, he turned on his heel and walked off.

"Poor boy!" exclaimed Aunt Caroline, as he passed out of sight. "We must be patient. We must do what we can for him. Had things been different, he could hardly have come with us. But why did you think Marion a girl?"

"I never heard of a boy named Marian."

"Oh—it's after General Marion. Perhaps my wretched writing made the 'o' look an 'a'. I didn't refer to our nephew?"

"No, you only said you hoped I'd like Marian, who was the same relation to Uncle Jim that I am to you," and Irma smiled, remembering that Aunt Caroline was only an aunt by courtesy,—in other words, an intimate friend of her mother's.

"Well, we are very fond of Marion—even if he isn't a real nephew—only we must all make allowances for him," then Aunt Caroline flitted off, while Irma wondered why allowances must be made for a tall, good-looking boy, who seemed well able to take care of himself.

Meanwhile, Marion, leaning against a rail at some distance from Irma, was on the verge of a fit of the blues.

"Thought I was a girl. Oh, yes, I suppose they have told her everything. Aunt Caroline ought to have had more sense. Anyway, I hate girls, and I'll try not to see much of this one."

Then Marion, to whom New York Harbor was no novelty, went within, while Uncle Jim joined Irma, and pointed out many interesting things. The great city they were leaving looked picturesque to Irma, as she gave its spires and high buildings a backward glance. The mammoth Liberty, standing on its little island, held her attention for a moment. Past the closely built shore of Long Island and the forts on the Westchester side, they were getting into deeper water, and Irma was straining her eyes in the direction of Sandy Hook, toward which Uncle Jim was pointing, when Aunt Caroline hurried up to her: "If you come in now, you can write a short letter to your mother."

"To my mother?"

"Yes, to send back by the pilot. But you must be quick."

Following her aunt, Irma was soon in the small saloon, where twenty or thirty persons were writing at small tables or on improvised lap-tablets. In one corner a ship's officer was tying up bundles of letters and putting them in the large mail bag that lay beside him.

Irma quickly finished her brief home letter. It was only a word to let them know she was thinking of them.

As she approached the mail steward, "No, sir, we 'aven't a stamp left," she heard him say, "heverybody's been writing. The stamps are hall gone—hat least the Hamerican."

"Oh, don't we need English stamps?" Irma turned to her aunt.

"No, dear. I am sorry he has no American stamps. I can enclose your letter with my own to Cousin Fannie, and she'll remail it."

"Oh, but I have stamps. I brought half a dozen with me." An old gentleman who had vainly asked the steward for a stamp stood near Irma. She had heard him express annoyance that he must entrust his letter to the pilot unstamped. "One can seldom trust a friend to put a stamp on a letter—still less a complete stranger—and this is very important."

"Excuse me," interposed Irma, stepping up to him. She wondered afterwards how she had dared. "Will you not take one of my stamps?" she said.

A broad smile brightened the old gentleman's face. "You certainly are long on stamps, and I am obliged to you for letting me share your prosperity." Then, stamping his letter, he dropped it into the mail bag.

"I'll take two," said a lady abruptly, approaching Irma, and without so much as "by your leave," she detached two from Irma's strip of four, and dropping a nickel into her hand, walked off with a murmured "Thank you." A second and younger lady then approached.

"Could you let me have two stamps?" she asked politely. "I overheard you say that you had some."

"Certainly," said Irma, and after thanking her, this applicant, with a pleasant "Fair exchange is no robbery," slipped into Irma's hand two Italian stamps. This seemed a much more gracious payment than the nickel. Later she recalled that the old gentleman had paid her nothing—and this, she decided, was the most courteous way of all.

The steward had fastened the bag when Marion rushed up to him. "Oh, say, steward, give me a stamp."

"'Aven't hany, sir."

"Well, you ought to have some."

"Mine are all gone, too," said Irma. "I had half a dozen a few minutes ago."

"You might have saved some for me," snapped Marion; "why should a girl write so many letters?"

"I wrote only one," began Irma. "You can give your letter to the pilot."

But Marion's only answer was to tear his letter into fragments. Then he followed the steward with the bag, and Irma was almost alone in the deserted saloon.

The letter she had just written was the last word she could send home for a week. It would be twice as long before she could hear from any of the family. She began to wish that she had gone back on the pilot boat. Why, indeed, had she ever left home? She should have waited until they could all visit Europe together. Now all kinds of things might happen to Chris or Rudolph or Tessie—or even to her father and mother—and it might all be over before she could hear a word. She began to be really unhappy, and again her eyes filled in a desperate feeling of homesickness.

After this first attack, Irma was, for a time, able to put the family out of her mind. At the first luncheon on shipboard, which she hardly tasted, her place at table was between Aunt Caroline and Marion. But at dinner when Marion appeared he dropped into the seat next to Uncle Jim, leaving his former place vacant.

"It's only one of Marion's notions," whispered Aunt Caroline. "I fear he is shy, and doesn't know what to say to you."

Irma was not comfortable in learning that Marion regarded her as a person to be avoided. "If only Marion had been a friendly girl how much pleasanter our party would be," she thought.

At first Irma felt she could hardly manage to live in her small stateroom. But when she had fastened to the wall the linen hold-all her mother had made, filled with various little things, and had stowed other small possessions in the drawer under the mirror, she saw the possibility of adapting herself to her cramped quarters. She soon had a regular program. She rose with the first morning bugle, and after her early bath, while Aunt Caroline dozed, dressed quickly.

Then she had a brisk walk on deck before breakfast, which Uncle Jim's party had at the second table.

Sunday morning—her second day at sea—Irma found a letter by her plate at breakfast.

"It's from Lucy," she cried, turning it over and over.

"A steamer letter," explained Uncle Jim. "Are you such a landlubber as not to know that in these days letters follow you regularly on your voyage?"

A moment later she discerned in a corner, "Care the Purser," and then she broke the seal.

"What news?" asked Uncle Jim, as she finished.

"All you'd expect from a letter written before I left home. I wonder how far we are now," she concluded with a sigh.

"Too far for you to swim back," answered Aunt Caroline, reading her thoughts.

Among the letters that Irma received daily after this, Mahala's was especially entertaining.

"To dream of a horse," she began, "is a sign of a letter, so I'm writing because I dreamt of a horse last night, though that isn't the way it's generally meant to work. Tessie's beginning to live up to many of the signs I've taught her, and when I told her I hoped your voyage wouldn't be unlucky because you were leaving Cranston Friday—just after you started she ran out of the room, and when I went on the steps to see if she'd gone over to the Flynns', well, just at that very minute something struck me on the head, and such a mess, all down my face and over my apron. When I got hold of Tessie she explained that she'd heard me say that if any one wished on an egg dropped from a second story window, the wish would come true—if the egg didn't break—but this egg certainly broke, and I hope it won't cause you ill luck. This wouldn't require mentioning, only I thought it might make you laugh if you happen to feel peaked the day you read this letter. We didn't punish Tessie, because she's feeling kind of bad about you, and she got scared enough when the egg broke on my head."

CHAPTER II

THE WESTERN ISLANDS

The first day or so of the voyage seemed long to Irma. She could not lie in a steamer chair, and pretend to read, as Aunt Caroline did. She had more than a suspicion that her aunt seldom turned the leaves of her book, and that left to herself she was apt to doze, although each morning Uncle Jim placed beside her chair a large basket containing books and magazines.

"Lean back, Irma," Uncle Jim would say, "you are not a real bird that you need perch on the arm of your chair. Lean back; I will fix your cushions—as Marion is not here to do this for you," he concluded mischievously.

"I wonder what Marion does with himself," interposed Aunt Caroline. "We see him only at meals, and I thought he would be such company for Irma."

"Irma doesn't need him," responded Uncle Jim. "Come, my dear, let us look at the steerage."

"Don't go below," protested Aunt Caroline. "You don't know what frightful disease you might catch."

"We'll only look over the railing," and Uncle Jim led Irma to a spot where she could look down at the steerage passengers, sitting in the sun on the deck below.

"It's not very crowded," explained Uncle Jim, "on the passage to Europe at this season. Most of those you see have a free passage because the authorities fear they may become public charges."

"How hard!"

"No, my dear. Many of them have better food and quarters here than they ever have on shore."

"Are there many sick among them?"

"The doctor told me of one poor woman who may not live until she reaches the Azores. She has been working in New Bedford, but when the doctors told her she could not live long, she was sure the air of the Western Islands would cure her. So her friends had a raffle, and raised enough for her passage, and a little more for her to live on after her arrival here, at least, that's what Marion told me."

"Marion!"

"Yes, he takes a great interest in the steerage. I dare say he knows those three ferocious-looking desperadoes in the corner."

"Desperadoes!"

"Well, they might be brigands, might they not? at least judging from their appearance. Most men returning at this season—and not a few of the women, too—are sent back by our Government because undesirable for citizenship."

"Oh!" exclaimed Irma. "That explains why so many wear strange clothes. They are really foreigners."

"Yes. The majority of them have probably never even landed."

As Irma turned away, her interest in the steerage increased rather than lessened. But when she asked Uncle Jim questions, she found he knew little about individuals. She wished that Marion would talk to her. She believed that he could tell her what she wished to know. But as the days passed Marion did not thaw out. It is true he usually reported the day's run to Irma, a little ahead of the time when it was marked on the ship's chart, and if she was not near Aunt Caroline when the steward passed around with his tea and cakes, he would usually hunt her up. But if she began to talk to him, he answered in the briefest words, and did not encourage further conversation.

One day, when he came to the table rather more animated than usual, she could not help overhearing him describe a visit he had made to the lower regions of the ship, where he had seen the inner workings of things. She listened eagerly to his description of the stoking hole with the flames weirdly lighting up the figures of the busy stokers. This interested her more than what he told of the machinery and the huge refrigerating plant.

"The doctor might have asked me, too. It's different from the steerage. Marion is very selfish, never to think of me. If there were more girls of my age, I wouldn't care. There isn't a boy in Cranston who would be so mean."

Soon after this, the day before they reached the Azores, Irma made the acquaintance of the one girl on board, near her own age. Hitherto Muriel had looked at her wistfully, not venturing to leave her governess, who talked French endlessly, as they paced the deck. But now, as Irma was watching a game of shuffleboard, played by older persons, Muriel approached and began a conversation, and soon the two were comparing their present impressions and their future plans.

"I'm awfully tired of Europe," said Muriel. "We go every year, but this time it may not be so bad, as we are to motor through Italy."

The most of this day the two new friends were together, separating only to finish the letters that they wished to mail at St. Michael's.

After dinner, when Irma went back to the dining saloon, the mail steward sat at a table with a scale before him, receiving money for the stamps he was to put on letters at Ponta Delgada.

"Why, here's my little lady of the stamps," cried a voice in Irma's ear, and turning, she recognized the little old gentleman, whom she had not seen since the first day.

Irma returned his greeting, and he went up with her toward the deck.

"It's so mild," she explained, "that my aunt said I might sit outside. I am so anxious to see land."

"Even if we were nearer shore, there's not moon enough to show an outline. Why are you so anxious to see land?"

"Because it will be my first foreign country. Except when we sailed from New York, I had never been out of New England."

"There are worse places to spend one's life in than New England," and the old gentleman sighed, as he added, "yet in the fifty years since I left it, I have been back only half a dozen times."

"I suppose you know the Azores," ventured Irma.

"Oh, yes, the country was very primitive in the old days. The interior, they tell me, has changed little, but the cities are more up to date."

"Cities?"

"Not large cities like ours in America, though Ponta Delgada is the third largest in Portugal. But there, young ladies of your age dislike guidebook information, at least out of school."

"Oh, please go on," begged Irma, and for half an hour her new friend talked delightfully about the Azores and other places.

"Ah, there's Uncle Jim," she exclaimed, as she saw her uncle approaching under one of the electric lights.

"I never thought of finding you out here alone," cried her uncle.

"Not alone," rejoined Irma, turning to introduce her new friend. But he had mysteriously disappeared.

"It is high time to come in, if the night air makes you see double," said Uncle Jim dryly. But Irma gave no explanations. How could she have introduced the old gentleman, when she did not know his name?

"Aunt Caroline says please hurry. They are in sight." Thus Marion's voice and repeated rappings waked Irma the next morning.

"Who are in sight?" she asked sleepily.

"The Azores, of course."

"Oh, dear," cried Irma, forgetting to thank Marion for his trouble. "Why," she wondered, "did I take this particular morning to oversleep?" Dressing at lightning speed, after a hurried repast she was soon on deck. Then, to her disappointment, there was nothing to see. The islands, wherever they might be, were veiled by a soft mist.

"They have been in sight for hours," some one said. Irma wished she had asked her steward to call her at dawn. Not until they were well upon Ponta Delgada did they have their first glimpse of St. Michael's toward noon, and the warmth of the sun was modified by the thin veil of mist. Gradually the mist dissolved, and not far away was the green shore, and behind, a line of low, conical mountains parallel with the coast. Then a white village appeared, and soon the spires and red roofs of Ponta Delgada.

Luncheon had been served early, and towards one o'clock the boat stopped, when still some distance from land. Large rowboats were pushing out from shore, and one or two tugs carrying the Portuguese flag.

"The tugs are bringing health and customs officers. We can't land until they have made their examination," Uncle Jim explained.

"How tedious to wait when we shall have so little time at the best!"

"Are we to go in those dreadful little boats?"

"Oh, it's a smooth sea; we'll get there safely enough."

"The town looks decidedly Spanish."

These and many similar remarks floated to Irma's ears. What impressed her most was the fact that she must descend the steep steps that the sailors were letting down from the side, and go ashore in a boat.

"It's safe enough," said Aunt Caroline. "Any one is foolish who remains on the ship. But I am willing to stay here myself."

So Aunt Caroline remained on the boat, and Irma, with Uncle Jim ahead and Marion behind, went down the long steps cautiously. When she had taken her seat in the large rowboat, she found herself near Muriel and her governess. The two girls were soon deep in conversation, while Marion, some distance away, sat listless and silent.

"Your brother isn't cheerful to-day," said Muriel, as the boat neared shore.

"He isn't my brother,—far from it," responded Irma, and unluckily at that moment Marion, rising to be of assistance to the ladies on landing, was near enough to hear both Muriel's remark and Irma's answer.

"Well, I am very glad not to be her brother," he thought, "and as to that other girl, she's exactly the kind I don't like." And in this mood Marion jumped hastily off when the boat pulled up, and running up the short steps, walked along the quay in solitary sulkiness, with his hands in his pockets.

"Your cavalier seems to have left you," said Uncle Jim mischievously, as he helped Irma ashore. "I wonder if he will condescend to join us on our tour of the town."

When they had pushed their way among the loungers at the wharf, however, they saw Marion standing near an open carriage, drawn by two underfed horses.

"How would this suit?" he asked. "The best carriages have been taken. You know our boat was almost the last."

"Over there are a couple of good automobiles looking for passengers."

For the instant Marion's face clouded. "Oh, of course," added Uncle Jim hastily. "I had forgotten. That wouldn't do. These horses may prove better than they look, and as we have no time to lose, let us start."

Before setting off, Uncle Jim turned about to see whether Muriel and Mademoiselle Potin had found a vehicle. Already they were seated in a carriage much like the one he had chosen, with horses that looked equally meek and hungry.

Then Uncle Jim's driver flourished and snapped his whip, and the horses went off at a lively pace. Irma, indeed, wished they would go more slowly, that she could get a better idea of the narrow streets. Yet even as they drove rapidly along she had a definite impression of clean pavements and small houses, many of them painted in bright colors. After they had left the little crowd near the wharf, the streets seemed deserted. Here and there an old man hobbled along, or a woman with a shawl over her head, or a girl with a large basket of fruit. They met oddly constructed carts, drawn by donkeys, and once they stopped to buy fruit from a man who bore a long pole on his shoulders, from one end of which hung a string of bananas, while from the other dangled a dozen pineapples.

"Fortunately," said Uncle Jim, "as our time is limited, there are not many important things to see in Ponta Delgada. We shall be obliged to look at so many churches in Italy that we can neglect those here."

"I'd like to see the church where Columbus and his sailors gave thanks, when they landed there after the storm."

"Santa Maria! Miles away!" cried Marion.

"Well," said Irma, slightly snubbed, "even if this isn't the place, it is interesting to remember that some of these islands had been settled years and years before America was discovered."

Soon they reached the famous garden, one of the two or three things best worth seeing in the town. When they walked through the great iron gates opened by a respectful servitor, at once Irma felt she was in a region of mystery. The three went along in silence under tall trees whose branches arched over the broad path.

Turning aside an instant, they gazed down a deep ravine, with banks moss-grown and covered with ferns. Far below was a little stream, and here and there the ravine was spanned by rustic bridges. Irma caught a glimpse of a dark grotto and a carved stone seat.

"It is rather musty here; let us hurry on," suggested Uncle Jim.

"Musty!" protested Irma. "It is like poetry."

"Well, poetry is rather musty sometimes."

Irma could not tell whether or not Marion was in earnest.

Farther in the garden they saw more flowers—waxlike camellias and some brilliant blossoms that neither she nor her companions could name. But there were other favorites—fuschias, geraniums, roses, in size and beauty surpassing anything Irma had ever seen.

"It reminds me of California," said Marion.

"Yes, there is the same soft air combined with the moisture that plants love. Europe has no finer gardens than one or two of these on St. Michael's. We'll have no time for another that belonged to José de Cantos. The owner died a few years ago and left it to the public, with enough money to keep it up. It has bamboo trees and palm trees and mammoth ferns and the greenhouses are filled with orchids. But we'll have to leave that for another visit. It is better now to go where we can get a general view of this part of the island."

In the course of their walk they had met groups of sightseers from the ship. But when they were ready to go back they had to turn to a group of old men and women at work on a garden bed, who, with gesticulations, directed them to the right path.

"Every one seems old here," said Irma, "even the men sweeping leaves from the paths with their twig brooms look nearly a hundred."

"The young and strong probably emigrate," said Uncle Jim.

On leaving the garden the coachman took them to the "buena vista," a hill where they had a lovely view of land and water. Far, far as they could see, stretched fertile farms with comfortable houses and outbuildings.

"Small farms," explained Uncle Jim, "ought to mean that a good many people are very well off, and yet it is said that most of the people here are poor."

When they were in the center of the town again, they sent their carriage away, and then Irma and Marion hastened to one of the little shops on the square, where the former bought post cards and the latter some small silver souvenirs. They rejoined Uncle Jim at the Cathedral door, but a glance at its tawdry interior contented them. Uncle Jim filled Irma's arms with flowers bought from one of the young flower sellers, and when at last they reached the wharf, they were among the last to embark for the ship. Muriel and Mademoiselle Potin were waiting for the same boat, and when they compared notes, the two girls found that they had seen practically the same things, though in a different order.

During their two or three hours on shore a fresh breeze had sprung up, and the waves were high. The boat, making her way with difficulty, sometimes did not seem perfectly under the control of the stalwart oarsmen. This at least was Irma's opinion, as she sat there trembling. Even Muriel, the experienced traveller, looked pale, and Irma wondered how Marion felt, seated near the bow with his face turned resolutely away from his friends.

"How huge the ship is," exclaimed Muriel, as they drew near the Ariadne, a great black hulk whose keel seemed to touch bottom.

For a moment Irma had a spasm of fear. What if this great, black thing should tip over some night! How could she make up her mind to live in it for another week!

Their rowers rested on their oars a few minutes, while other boats just ahead were putting passengers aboard. Looking to the decks so far above, Irma recognized Aunt Caroline waving her handkerchief. If only she could fly up there without any further battling with the waves!

"Come, Irma," said Uncle Jim. "There isn't the least danger. I will stay on the boat until the last, and you can step just ahead of me."

All the others, even Muriel and Mademoiselle, had gone up the stairs before Marion. He was just ahead of Irma, and when he had his footing, he stood a step or two from the bottom, to help Irma. The men had difficulty in steadying the boat. But one of them held Irma firmly, until her feet were on a dry step. Then, as Marion extended his hand to her, she put out hers when, it was hard to tell how it really happened, Marion's foot slipped, and instead of helping Irma he fell against her, almost throwing her into the tossing waves.

Irma, however, fortunately kept her presence of mind. Not only did she grasp the guard rope quickly, but with her other arm she held Marion firmly. Their feet were wet by the dashing waves, but there was no further damage. They had had a great fright, though Marion seemed to suffer the most. When Irma relaxed her hold, she could walk up to the deck unaided, but Marion had to be supported by a boatman, until Uncle Jim, closely following, drew his arm through his, and so helped him to the deck.

Not even Aunt Caroline realized what had happened, when Irma said she must go to her room to change her wet shoes. This she did quickly, as she wished to see all she could of the coast of beautiful St. Michael's.

"Tell me now," said Aunt Caroline, from the depths of her chair, "was going ashore really worth while?"

"Yes, indeed, you shouldn't have missed it."

"Ah, well, I was there years ago, visiting cousins who lived there. But they are now dead, and everything would be so changed. I am told they have electric lights, not only in Ponta Delgada, but in the villages near by, and I don't suppose you met a single woman in the long capote, with its queer hood, nor even one man in a dark carpuccia."

"Why, yes," responded Irma, smiling, "I met them on some post cards, but nowhere else."

Irma hastened through her dinner that evening. Marion did not appear, but the old gentleman came to her, and placed himself in Aunt Caroline's vacant chair. He entered into a long conversation—or rather a monologue, since in answer to Irma's brief questions he did most of the talking.

He told Irma how isolated the islanders were from one another, so that on Corvo, and one or two of the others, if the crops fail, or there is any disaster, they signal for help by means of bonfires. Some of them have mails to Portugal only once in two or three months. Ponta Delgada is much better off, with boats at least twice a month to Lisbon, and fairly good communication with other places. "But if I had time," continued the old gentleman, "I could find nothing more healthful and pleasant than a cruise around these nine Western Islands."

"How large are they?" asked Irma abruptly.

"Well, they cover more water than land. St. Mary, St. Michael's nearest neighbor, is fifty miles away, and Terceira, the next neighbor, is ninety miles off. But St. Michael's, the largest of them all, is only thirty-seven miles long by nine broad, and Corvo, the smallest, you could almost put in your pocket with its four and a half miles of length and three of breadth. But what they lack in size they make up in climate."

"Then I don't see why the men are so ready to leave the islands."

"To make money, my child. If Portugal were better off, the islands would share her prosperity. But they share the political troubles of the mother country. Many farms produce barely enough for the tenants, who have to deal with exacting landlords. But some of the large landowners, especially those who raise pineapples, grow rich. The oranges and bananas that they send to Lisbon, and their butter and cheese, too, make money for the producers. But the islands won't be really prosperous until they have more manufactures."

In his soliloquy, the old gentleman seemed to have forgotten Irma, and she was on the point of calling his attention to the particularly high and rugged aspect of the coast they were then passing, when he continued, "St. Michael's, I believe, has made a good beginning with carriages and furniture for its own use, and soap and potato alcohol for export, and in time—but, my dear child, I am boring you to death——"

"Oh, no, but isn't the coast beautiful, with that veil of mist around the tops of those mountains; what a pity it grows dark."

"What a pity it has grown so damp that I must order you in," said the old gentleman kindly, and though he was neither uncle nor aunt, and no real authority, Irma found herself following him within, as she turned her back to the Western Islands.

CHAPTER III

TOWARD THE CONTINENT

"Aren't you tired of hearing people wonder when we shall arrive at Gibraltar?"

"They needn't wonder. This is a slow boat, but we have averaged about three hundred and twenty-five miles every day, so we must get in early Tuesday unless something unusual happens. A high wind may spring up, but even then we are pretty certain to come in sight of Gibraltar before night."

"Oh, I can hardly wait until then," began Irma. "I hope we can go up on top of the Rock, and down in the dungeons, and everywhere." Muriel, who was walking with Irma and Marion, looked surprised at her friend's enthusiasm, and even a trifle bored.

"Don't talk like a school book," she whispered, and Irma, reddening, glanced up at Marion, to see if he shared Muriel's strange distaste for history. But he gave no sign.

Since leaving the Azores, Muriel's frank friendliness for Irma had added much to the pleasure of the two girls. Though they had been brought up so differently, they had much in common. Muriel's winters were usually spent there, but she had also travelled widely. She had been educated by governesses, and yet Irma could but notice that she was less well informed in history and had less interest in books than many of her own friends at home. Irma did not compare her own knowledge with Muriel's, but an impartial critic would probably have decided that, whatever might be the real merits of the two systems, Irma had profited the more from the education given her. In modern French and German, however, Muriel certainly was proficient, and when she complained of Mademoiselle Potin, Irma would tell her to be thankful that she had so good a chance to practice French.

Since the day at St. Michael's, Marion had ceased to avoid Irma, and though he spent little time with her, he was evidently trying to be friendly. He never referred to his misadventure coming on board. Aunt Caroline had brought Irma his thanks.

"He is very nervous, as you must have noticed," she said, "and he may be unable to talk to you about this. For he feels that he has disgraced himself again; and though he is incorrect in this, still I appreciate his feelings, and hope you will accept his thanks."

"Why, there's really nothing to thank me for," began Irma.

"Oh, yes, my dear, we all think differently. You certainly have great presence of mind. Poor Marion."

In spite of Aunt Caroline's sympathetic tones, Irma did not pity Marion. He was a fine, manly-looking boy, and the sea air had brought color to his face, while his fretful expression had almost gone.

After the first day or two at sea Irma had begun to make new acquaintances. Among them was a little girl who greatly reminded her of Tessie as she had been a few years earlier. So one day she called her to listen to the steamer letter from Tessie, that she had found under her plate that morning.

"Dear Irma, when you read this—for I hope Uncle Jim will give my letter to you—you will be far out on the ocean, where it is very deep, with no islands or peninsulas in sight, and I hope you will be careful not to fall overboard. But please look over the edge of the boat once in a while to see if there are any whales about. Of course, I hope they won't be large enough to upset your steamboat, but if you see one, please take a photograph and send it to me, for I never saw a photograph of a truly, live whale.

"I can't tell you any news, because I am writing this before you leave home, so you'll be sure to get it. I would feel too badly to write after you get started.

"From your loving Tessie."

The letter interested little Jean very much. She had already heard about Tessie and Nap, and now she rushed to the edge of the deck, and when Irma followed her, the child upturned to her a disappointed face.

"I can't see one."

"One what?"

"A whale—and Tessie will be so disappointed. I know she wants that photograph."

"No matter, I can take your photograph, only you must smile."

So Jean smiled, and the photograph was taken with the camera that Uncle Jim had given Irma.

"It will be more fun to look for Gibraltar than for whales. To-morrow we must all have our eyes open."

"What's Gibraltar?"

"The great big rock where we are going to land."

"I don't want to land on a rock," pouted Jean. "I want to go ashore."

"Oh, we'll go ashore, too."

That evening there was a dance on the ship. The upper deck was covered with canvas, and canvas enclosed the sides. Gay bunting and English and American flags brightened the improvised ballroom, and most of the younger passengers, as well as not a few of the elder, spent at least part of the evening there.

"Hasn't Marion been here?" asked Aunt Caroline, when she and Uncle Jim appeared on the scene.

"I haven't seen him," responded Irma.

"What a goose he is!" exclaimed Uncle Jim.

"He's very grumpy, isn't he?" commented Muriel, but Irma made no reply.

On Tuesday Irma was on deck early. In the distance a thin dark line after a time took on height and breadth.

"Cape Trafalgar!" some one exclaimed.

"Europe at last!" thought Irma.

"What do you think of Spain?" asked Uncle Jim, standing beside her.

"It seems to be chiefly brown cliffs. And so few villages! Where are the cities?"

"You'll find seaports only where there are harbors. They are not generally found on rocky promontories."

Irma turned about. Yes, the speaker was indeed Marion, whose approach she had not observed.

"Oh, Cadiz is not so very far to the north there," interposed Uncle Jim, in an effort to throw oil on the troubled waters, "and we cannot tell just what lies behind those heights. What is there, Marion? You've been in Spain."

But Marion had disappeared.

After passing Trafalgar, the Ariadne kept nearer shore. Now there was a house in sight, again a little white hamlet lying low at the base of the brown, bare cliffs.

Far ahead the clouds took on new shapes, and did not change. Could that be the huge bulk of Gibraltar, seen through a mist?

Uncle Jim laughed when Irma put the question to him.

"You are looking in the wrong direction."

"Then it must be Africa. Oh, I wish we might go nearer."

"In that case you might miss the Rock altogether, and take the chance, too, of being wrecked on a savage coast."

But the Spanish shore gained in interest. Here and there small fishing boats pushed out. Sometimes steamboats were in sight, smaller than the Ariadne yet of good size, traders along the coast from London, perhaps, to Spanish or French ports. Muriel and Irma amused themselves guessing their nationality, with Uncle Jim as referee. Strange birds flew overhead. Then a town, grayish rather than white, and a lighthouse on the height above.

"Tarifa," some one explained, and those who knew said that Gibraltar could not be far away. Soon Irma, who had kept her face toward the African shore, was startled by a voice in her ear. "The Pillars of Hercules are near; people are so busy gathering up their things to go ashore that I was afraid you might go to your stateroom for something, and so miss them."

"You are very kind to think of me," said Irma, turning toward Marion, for it was he who had spoken. "How I wish we were to land at some of those strange African places."

"Tangiers might be worth while, but I love this distant view of the mountains."

"Do you know the name of the African pillar?"

"Yes—Abyla! and Gibraltar, formerly known as Calpé, was the other. It's a pity we won't have time to go to the top of the Rock. The Carthaginians used to go up there to watch for the Roman ships. The British officer on guard at the top of the Rock must have a wonderful view. Some one told me you can see from the Sierra Nevadas in Spain to the Atlas in Africa. Just think of being perched up there, fourteen hundred feet above the sea. If only we could have a whole day at Gibraltar, we might see something, but now——" and the old expression of discontent settled on Marion's lips.

"Oh, well, we can probably go around the fortifications," responded Irma, trying to console him.

"The fortifications! Oh, no, there are miles of them, and the galleries are closed at sundown, so that we couldn't get into them, even if we had a pass,—I suppose that's what they call it."

"Well, at least we'll see the town itself, and we can't help running upon some of the garrison, for there are several thousand soldiers and officers."

"Oh, I dare say, but it isn't the same thing as visiting Gibraltar decently. Uncle Jim ought to have planned a trip through Spain. It would be three times more interesting than Italy."

Irma, who had visited neither country, did not contradict Marion. Enough for her even a short stay at one of the most famous places in the world, the wonderful fortress that the British had defended and held so bravely during a four years' siege more than a century ago.

"Marion is a strange boy," thought Irma. "I wonder why he tries to make himself miserable."

After passing the jagged and mysterious Pillars of Hercules, Irma soon saw the huge bulk of Gibraltar not far off, and then it seemed but a short run until they had gained the harbor. Her heart sank when she found they were to anchor some distance from shore, for though the water was still and calm, she did not like the small boats. But Uncle Jim laughed at her fears, assuring her that they would be taken off in a comfortable tender.

The tender was slow in coming, and during the time of waiting some passengers fretted and fumed. "If they don't get us in by sunset they may not let us land at all. There is such a rule."

When others asserted that there was no such rule, some still fretted, because after five there would be no chance to visit the fortifications.

"Come, Irma," said Uncle Jim, "these lamentations have some foundation in fact. But Gibraltar's a small town, and we'll improve our two shining hours, which surely shine with much heat, by getting our bearings here."

"There's plenty to see," responded Irma. "I suppose those are English warships in their gray coats, and there's a German flag on that great ocean liner. It seems to be crowded with men, immigrants, I suppose, for they are packed on the decks like—like——"

"Yes, like flies on flypaper." And Irma smiled at the comparison.

Not far from a great mole that stretched out, hot and bare in the sun, two clumsy colliers were anchored; here and there little sailboats darted in and out, and the small steam ferries plied backward and forward to the distant wooded shore, which Uncle Jim said was Algeciras. But it was the gray mass of Gibraltar itself that held Irma's attention. The town side, seen from the harbor, though less steep than the outline usually seen in pictures, was yet most imposing. Along its great breadth, lines of fortifications could be discerned, and barracks, grayish in color, like the rock itself. There were lines of pale brown houses that some one said were officers' quarters, and an old ruin, the remains of an ancient Moorish castle.

A number of passengers were to land at Gibraltar to make a tour of Spain, among them little Jean. Irma had turned for a last good-by to them, when Aunt Caroline, joining her, told her that people were already going on board the tender.

"What are your exact sensations, Irma?" whispered Uncle Jim, mischievously, "on touching your foot to the soil of Europe? You know you'll wish to be accurate when you record this in your diary. Excuse me for reminding you."

"Come, come," remonstrated Aunt Caroline. "Irma may have to record her feelings on finding that every conveyance into the town has been secured by other passengers, while a frivolous uncle had forgotten his duty."

But even as she spoke, Marion approached them, walking beside a carriage, to whose driver he was talking.

"Well done, Marion; so you jumped off ahead, and though it's a queer-looking outfit, it will probably have to suit your critical aunt."

"It's much better than most carriages here," replied Marion, a trifle indignantly; "some of them have only one horse."

"You are very thoughtful, Marion," said Aunt Caroline, as they took their places in the brown, canopied phaeton. "No, not now, not now," she cried, as a tall, dignified Spaniard thrust a basket of flowers toward her. "Orange blossoms and pansies are almost irresistible, but it is wiser to wait until we are on our way back to the boat."

Marion's face had brightened at Aunt Caroline's praise, and thus, in good humor, he chatted pleasantly with Irma as they drove on. So long was the procession of vehicles ahead of them that their own carriage went slowly through the narrow street. A Moor in flowing white robes and huge turban attracted Irma's attention, as she observed him seated in the doorway of a warehouse on the dock. Farther on they saw a boy of perhaps seventeen, similarly arrayed, pushing a baby carriage.

"The servant of an English officer," Uncle Jim explained. "Look your hardest at him, for we shall not see many of his kind after this. It is now past the hour when the Moorish market closes. After that all Moors must be out of the town in their homes outside the gates, except those employed in private families."

As the carriage turned into the long, crooked thoroughfare that is the chief business street of Gibraltar, the driver pulled up before a small shop that had a sign "New York Newspapers."

"He knows what we need; run, Marion, and get us the latest news."

"Yes, Aunt Caroline." But there was disappointment on Marion's face when he returned a few moments later.

"There was another liner in early this morning, and all the latest papers are gone. They have only the European editions of New York papers, and the two I could get are a week old."

"No matter, son, you did the best you could."

"These are two or three days later than the last we saw in New York, and as they have no bad news, or I might say no news at all, we may be thankful. But we must move on. In this bustling town there's no time to stand still."

"What interesting shops!" began Irma.

"Oh, they're ugly and dingy," said Marion.

"In Europe we're almost bound to admire the dingy, if not the ugly," returned Uncle Jim.

"Where are we going?" asked Aunt Caroline.

"Out to the jumping-off place," said Marion. "That won't take long. After that we can go shopping, or at least you can."

"There's a great deal I can enjoy," said Irma pleasantly.

Then they drove on past a park where boys were romping on a gravelled playground, while in another portion officers played cricket. They passed many soldiers in khaki, and here and there a red coat. A sloping road led up to a set of officers' quarters, detached houses, shaded by tropical trees. Here they noticed a girl on horseback, a young girl of about Irma's age, with her hair hanging in a long braid beneath her broad, felt hat, and not far from her two or three girls driving.

At the little Trafalgar burying-ground their driver paused a moment that they might read the inscriptions on some of the monuments, marking the burial places of many brave English patriots. They had time for a bare glance at the old Moorish garden across the road.

"This is the jumping-off place," cried Marion, as they came in sight of the water. At one side was a pool where the soldiers bathed, and near by the officers' bathing-houses.

"I know that I should be turning back," said Aunt Caroline. "My special shop is up Gunners' Lane, and when I have been left there, you others may inspect the town. At the most there isn't much time."

Marion, however, insisted on staying with Aunt Caroline.

"Very well, then. After we have spent all our money on antiques, we'll meet you in front of the post office. I noticed it as we came along; and you must surely be there at half past seven."

"Yes, yes," promised Uncle Jim. "Now, my dear," he said, as he and Irma returned to the main street, "we can let the carriage go, as we shall probably spend our time passing in and out of these shops."

It was now after six, and the street was thronged. Many were evidently working people on their way home from their day's labors, but some were shoppers with baskets on their arms, and others were evidently tourists, loitering or running in and out of the shops. It was a good-natured crowd that pushed and jostled and overflowed into the middle of the street. Among the throng were many sailors from the ships of war.

For some time Uncle Jim with Irma gazed in the windows, and wandered in and out of the most promising shops. In his shopping he had one invariable method. No matter what the object, or its cost, he always offered half the price asked.

"Is it fair," asked Irma timidly, "to beat them down?"

"It's fair to me," he replied. "In this way I stand a chance of getting things at something near their value."

"How much is that?"

"Usually one half the asking price. Listen."

So Irma listened while a lady near by was bargaining with the Hindu salesman.

"Never in my life has such a price been known," he protested, as the lady held up for inspection a spangled Egyptian scarf. The lady advanced reasons for her price.

"I cannot make my bread," cried the man, "if I throw my goods away." Yet he thrust the scarf into the lady's hand, and then sold her a second at the same price, without a word of argument.

"These men are Orientals," explained Uncle Jim, "and this is their way of doing business. They mark a thing double or treble what they expect to get, and would be surprised if you should buy without bargaining. This man probably goes through this process a dozen times a day after an ocean liner has come into port, and doubtless congratulates himself on the extent of his trade."

Uncle Jim further explained that things made in India and Egypt were brought to Gibraltar at small expense, and could be sold for much less than in America or France or even Spain. So he bought spangled scarfs and silver belt buckles, and a number of other little things that he said would exactly suit Aunt Caroline. But Irma bought nothing, tempting though many things were. Realizing that all Italy lay before her, she did not care to draw yet on the little hoard that she was saving for presents for those at home. After they had visited a number of shops, Irma remembered that she had several letters to post.

"You can't buy stamps at the post office," said Uncle Jim. "That's one of the peculiarities of Europe. Stamps are sold where you least expect to find them, usually in a tobacconist's. I will go to the shop over there and get some."

A moment later, when Uncle Jim returned with the stamps, a gentleman whom Irma did not know was with him.

"This is my old friend, Gregory," he said, presenting him to Irma. "If we had not that appointment to meet your aunt and Marion here, I would take you to the hotel to see Mrs. Gregory. It is impossible for her to come out, and I am sorry to miss her."

"Yes, and she will be disappointed at not seeing you. But she is extremely tired, as we arrived on the German liner this morning, and to-morrow we start on a fatiguing trip through Spain."

"If it would not take more than a quarter of an hour, there is no reason why you should not go back to the hotel, Uncle Jim. I can wait here, for Aunt Caroline and Marion may come along at any minute."

After a little thought, Uncle Jim decided that Irma's plan was practicable. But he wished her to wait in a phaeton, to whose driver he gave explicit directions not to go more than a block from the post-office door.

But when after a quarter of an hour neither Uncle Jim nor Aunt Caroline had appeared, Irma was greatly disturbed.

"I wouldn't make a good Casabianca," she thought.

Some of her friends from the Ariadne passed her, and one or two stopped to advise her. "They would have been here ten minutes ago, had they expected to meet you here." "No, they are probably waiting for you at the landing." Even the driver shared this view, and at a quarter of eight Irma drove down to the boat escorted by the carriage in which sat Muriel and her mother and governess.

"You must stay with us," said Muriel, "until you find your aunt. She's probably on the tender."

But just at this moment a hand was laid on Irma's arm. Turning about, she saw that the little old gentleman was beside her.

"Excuse me," he said, "but your aunt is over there. She has not yet gone aboard the tender." As he pointed to the left, Irma saw Aunt Caroline and Marion under the electric light near the waiting-room. When she had reached them the old gentleman was nowhere in sight.

"We forgot that we had agreed on the post office," explained Aunt Caroline, "at least I thought it was the landing. Then we were afraid to go back, for fear of making matters worse. But what has become of your uncle?"

Irma's explanation was not particularly soothing to her aunt.

"If he isn't here soon, he will lose his passage on the Ariadne. We must go on, even without him. Some other boat for Naples will come soon. We can better spend extra time at Naples than wait here."

"But suppose something has happened to him!" suggested Marion.

"I am not afraid. This isn't the first time he has missed boats—but still——" Aunt Caroline seemed to waver. The last whistle had been blown when a figure was seen making flying leaps towards the boat. It was Uncle Jim, who later explained that he had forgotten to look at his watch until his friend suddenly reminded him that he had but five minutes in which to reach the boat. Thereupon he had decided that his only way was to run as if for his life. Almost exhausted, he was evidently not a fit subject for reproof, and Aunt Caroline merely expressed her thankfulness that he had not been detained at Gibraltar.

CHAPTER IV

AWAY FROM GIBRALTAR

As the Ariadne steamed away from Gibraltar, the harbor looked very unlike that of the afternoon. It was now cool, and dark except when lit by flashes from the searchlights. The warships that had looked so sombre in the afternoon were now outlined by rows of tiny electric lights, and myriads of lights twinkled from the town lying along the face of the Rock.

With so much beauty outside, Irma could not leave the deck of the Ariadne. As she stood there alone, the little old gentleman approached. "There is to be a sham fight in the harbor to-night. That accounts for the unusual illumination."

"It is too beautiful for words. I must stay until we see the other face of the Rock—the picture side."

"I wish I could stay, but I came only to bring you this. It may be of use to you, as you can have no dinner."

"No dinner! But I wish none."

"Some of your friends, however, may need something more substantial than the view. The company is saving an honest penny by allowing those who went ashore to abstain from dinner. It would have been served as usual, it was ready, the stewards say, if there had been passengers here to eat it."

"But they were all ashore."

"The passengers coming on at Gibraltar were here. Others could have been, but they preferred sightseeing at Gibraltar. Consequently they were punished."

The company's meanness seemed absurd, but as the old gentleman departed, Irma thanked him warmly for his gift,—a good-sized basket filled with fruit and cakes.

For some time Irma strained her eyes for a glimpse of the other side of the Rock. At length, against the sky rose a huge bulk that might have escaped a less keen vision. Almost instantly a passing cloud darkened the sky, and the giant became invisible.

When Irma went inside she found a discontented crowd gathered in passageways and in the library. Loud were the complaints that greeted her of the company's cruelty in omitting dinner.

"We went ashore without even our usual afternoon tea, and no one had time to think of food at Gibraltar."

Irma held out her basket. "A fairy godfather visited me," she said, "but I really do not know just what he gave me. Come, share it with me."

Aunt Caroline looked surprised; Uncle Jim gave an expressive whistle, while even on Marion's face was an expression of curiosity.

"I do not even know what is in the basket," repeated Irma, "though the fairy godfather said it held fruit and cakes."

"I should say so," exclaimed Uncle Jim lifting the cover. "What fruit! And that cake looks as if it had been made in Paris. Just now these are much more attractive than those spangled scarfs I wrestled for with that Hindu. By the way, Irma, are these for show or use? They look too good to eat."

"Try them and see," answered Irma.

"I'd be more eager to eat if I knew the name of the fairy godfather."

"I don't know it myself," said Irma.

"This feast will dull our appetites for the nine o'clock rarebit," interposed Uncle Jim, who had made a test of the basket's contents.

"I am sure a fairy godfather wouldn't use poison," and Aunt Caroline followed Uncle Jim's example.

When Irma turned to offer the basket to Marion, he had left the group.

"Poor boy," exclaimed Aunt Caroline. "He told me he felt very faint. It seems he had little luncheon. Perhaps we shall find him in the dining saloon."

But when they descended to the dining saloon, Marion was not there, nor did they see him again that night. Yet, if she could not share the old gentleman's gift with Marion, Irma found Muriel most grateful for a portion. For some time the two girls sat together at one end of the long table, comparing notes about Gibraltar. They stayed together so late, indeed, that just before the lights were put out Aunt Caroline appeared.

"Why, Irma, my dear, after this exciting day I should think you would need rest earlier than usual."

"Perhaps so, Aunt Caroline. But the day has been so exciting that I cannot feel sleepy."

"It has grown foggy," said Aunt Caroline, as they went to their room. "I do not like fog, and I am glad that we have but two or three more nights at sea."

Once in her berth Irma soon slept. She thought indeed that she had been asleep for hours, when suddenly she woke. It must be morning! But as she opened her eyes, not a glimmer of light came through the porthole. What had wakened her? Then she realized that the boat was still. What had happened? She was conscious of persons walking on the decks above, of voices far away, even of an occasional shout. Ought she to waken Aunt Caroline? While her thoughts were running thus, she had jumped from her berth, and a moment later, in wrapper and moccasins, had made her way to the deck. A few other passengers were moving about, and a group of stewards and stewardesses stood at the head of the stairs, as if awaiting orders.

"What is it?" she cried anxiously. Before her question had been answered, some one shoved her arm rather roughly. Looking up she saw that Marion had come up behind her.

"What are you doing here?" he said brusquely. "You will get your death. It is very cold."

Irma shivered. In spite of her long cape she was half frozen. The night air was chilly, and it was on this account that Marion pulled her from the open door.

"Are we in danger? I thought I wouldn't wake Aunt Caroline until I knew."

At this moment Marion, unfortunately, smiled. He was fully dressed and wore a long overcoat. With his well-brushed hair he presented a strong contrast to poor, dishevelled Irma. Naturally, then, she resented his smile, occasioned, she thought, by her untidy appearance.

"You are a very disagreeable boy," she cried angrily. "I wish I had told you so long ago." Thereupon Irma turned toward the stewards, among whom she recognized the man who took care of her stateroom.

"No, Miss, we're not in danger," he answered. "It's foggy, and there was something wrong about signals, but we stopped just in time to get clear of a man-of-war. It would have been pretty bad if she had run into us. So go back to your bed, Miss; it's all right now, and we're starting up again."

Marion was unhappy as he watched Irma walking downstairs. Evidently he had in some way offended her; but how? She was an amiable girl; he was sure of this. Therefore his own offence must have been very serious. "It is no use," said Marion bitterly, "I cannot expect people to like me. Of course, she started with a prejudice, and she will never get over it."

Now Irma, when she returned to her berth, though reassured by what the steward had said, did not at once fall asleep. For a long time she lay with eyes wide open listening to many strange sounds, some real, some imaginary. But at last, when a metallic hammering had continued for hours, as it seemed to her, she was quite sure something had happened to the boilers, and she drowsily hoped the Ariadne would keep afloat until morning. It would be so much easier to get off in the lifeboats by daylight. Then she must have fallen asleep. At least the next thing of which she was aware was Aunt Caroline's loud whisper to the stewardess. "We won't disturb her. She can sleep until luncheon."