Brenda's Bargain: A Story for Girls

Helen Leah Reed

Brenda's Bargain

A Story for Girls

BY HELEN LEAH REED

Author of "Brenda, Her School and Her Club" "Brenda's Summer at Rockley," "Brenda's Cousin at Radcliffe"

ILLUSTRATED BY ELLEN BERNARD THOMPSON

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1903

Copyright, 1903,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Published October, 1903

UNIVERSITY PRESS

JOHN WILSON AND SON

CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

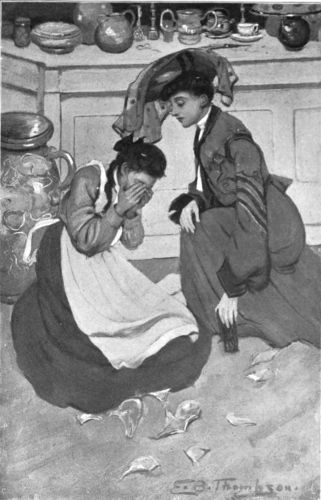

But what startled Brenda was the sight of a girl sunk in a heap beside the broken glass

CONTENTS

| I. | The Broken Vase | 1 |

| II. | A Family Council | 14 |

| III. | Brenda at the Mansion | 26 |

| IV. | An Exploring Tour | 40 |

| V. | Philip's Lecture | 51 |

| VI. | In the Studio | 62 |

| VII. | In Difficulties | 73 |

| VIII. | The Fringed Gentian League | 86 |

| IX. | Nora's Work—and Polly | 97 |

| X. | Arthur's Absence | 107 |

| XI. | Seeds of Jealousy | 120 |

| XII. | Doubts and Duties | 126 |

| XIII. | The Valentine Party | 139 |

| XIV. | Conciliation | 147 |

| XV. | War at Hand | 158 |

| XVI. | The Artists' Festival | 168 |

| XVII. | Ideal Homes | 180 |

| XVIII. | Where Honor Calls | 193 |

| XIX. | They Stand and Wait | 204 |

| XX. | Weary Waiting | 215 |

| XXI. | An October Wedding | 227 |

| XXII. | The Winner | 239 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| "But what startled Brenda was the sight of a girl sunk in a heap beside the broken glass" | Frontispiece |

| "Waiting for a car they had sat down on a wayside seat" | 62 |

| "'I think I hear some one coming upstairs'" | 77 |

| "They walked through the long galleries" | 136 |

| "She seemed to take but a languid interest in the world around her" | 224 |

| "Brenda had never looked so well" | 235 |

BRENDA'S BARGAIN

I

THE BROKEN VASE

One fine October afternoon Brenda Barlow walked leisurely across the Common by one of the diagonal paths from Beacon Street to the shopping district. It was an ideal day, and as she neared the shops she half begrudged the time that she must spend indoors. "Now or never," she thought philosophically; "I can't send a present that I haven't picked out myself, and I cannot very well order it by mail. But it needn't take me very long, especially as I know just what I want."

Usually Brenda was fond of buying, and it merely was an evidence of the charm of the day that she now felt more inclined toward a country walk than a tour of the shops.

Once inside the large building crowded with shoppers, she found a certain pleasure in looking at the new goods displayed on the counters. It was only a passing glance, however, that she gave them, and she hastened to get the special thing that she had in mind that she might be at home in season to keep an appointment. Her errand was to choose a wedding present for a former schoolmate, and she had set her heart on a cut-glass rose-bowl. Yet as she wandered past counters laden with pretty, fragile things she began to waver in her choice.

"Rose-bowls!" the salesman shrugged his shoulders expressively; "they are going out of fashion." And Brenda wondered that she had thought of a thing that was not really up to date; for, recalling Ruth's wedding presents, she remembered that among them there were not many pieces of cut-glass, and not a single rose-bowl.

At last after some indecision she chose a delicate iridescent vase, beautiful in design, but of no use as a flower holder. Its slender stem looked as if a touch would snap it in two. It cost twice as much as she had meant to spend for this particular thing, and had she thought longer she would have realized that so fragile a gift would be a care to its owner. Self-examination would have shown that she had made her choice chiefly to reflect credit on her own liberality and good taste. But her conscience had not begun to prick her as she drew from her purse the twenty-dollar bill to pay for the purchase.

A moment later, as Brenda walked away, a crash made her turn her head. A second glance assured her that the glittering fragments on the floor were the remains of her beautiful vase. But what startled Brenda more than the shattered vase was the sight of a girl sunk in a heap beside the broken glass. She recognized her as the cash-girl whom the clerk had told to pack her purchase. Evidently she had let the vase fall from her hands, and as evidently she was overcome by what had happened.

Had she fainted? Brenda, bending over her, laid her hand on the girl's head. Aroused by the touch, the child raised her head, showing a face that was a picture of misery. Sobs shook her slight frame, and she allowed a kind-looking saleswoman who came from behind a counter to lead her away from the gaze of the curious. Meanwhile the salesman who had served Brenda brushed the bits of glass into a pasteboard-box cover.

"I'm very sorry," he said politely, "but we cannot replace that vase. As I told you, it was in every way unique. However, there are other pieces similar to it—a little higher-priced, perhaps—but we will make a discount, to compensate—"

"But who pays for this?" Brenda interrupted, inclining her head toward the broken glass.

"Oh, do not concern yourself about that, it is entirely our loss. Of course, if you prefer, we can return you your money, but still—"

"Will they make that poor little girl pay for the glass?"

"Well, of course she broke it; it was entirely her fault; she let it slip from her fingers. She is always very careless."

"But I paid for it, didn't I?" asked Brenda. "That is my money, is it not?" for he still held a bill between his fingers.

"Why, yes; as I told you, you can have your money back."

"I have not asked for my money, but I should like to have the vase that I bought to take home with me. It will go into a small box now."

"Do you mean these pieces?" The salesman was almost too bewildered to speak.

"Why, of course, they belong to me, do they not?" and a smile twinkled around the corners of Brenda's mouth. At last the salesman understood.

"It's very kind of you," he said, emptying the pieces from the cover into a small pasteboard box. "Mayn't we send it home?"

"Yes, after all, you may send it. Please have it packed carefully;" and this time both Brenda and the salesman smiled outright.

"It's the second thing," said the latter, "that Maggie has broken lately. She's bound to lose her place. It took a week's wages to pay for the cup, and I don't know what she could have done about this. It would have taken more than six weeks' pay."

"I should like to see her," said Brenda. "Can I go where she is?"

"Certainly, she's in the waiting-room, just over there."

"Come, come, Maggie," said Brenda gently, when she found the girl still in tears; "stop crying, you won't have to pay for the glass vase. You know I bought it, and I'm having the pieces sent home."

As the girl gazed at Brenda in astonishment her tears ceased to flow from her red-rimmed eyes. But the young lady's words seemed so improbable that in a moment sobs again shook her frame.

"It cost twenty dollars," she said; "I heard him say it. I can't ever pay it in the world, and I don't want to go to prison."

"Hush, hush, child!" cried a saleswoman who had stayed with her. "You must stop crying, for I have to go back to my place."

She looked inquiringly at Brenda, and Brenda in a few words explained what she had done.

"You are an angel," said the kind-hearted woman; "and if you can make Maggie understand, perhaps she will stop crying."

Now at last the truth had entered Maggie's not very quick brain. Jumping to her feet she seized Brenda by the hand.

"You mean it, you mean it, and I won't have to pay! But I'll pay you some time. Oh, how good you are! How good you are!"

"There, Maggie, you'll frighten the young lady, and you're not fit to go back to the store. Your eyes would scare customers away. I'll take word that you're sick, so's you can go home now; and, Miss, I hope Maggie'll always remember how kind you've been."

As the woman departed Brenda had a new idea, and when the message came that Maggie might go home she asked the little girl to meet her at the side door downstairs when she had put on her hat. "I want to talk with you," she said, "and will walk with you a little way."

Such condescension on the part of a beautiful young lady was enough to turn the head of almost any little cash-girl, and Maggie could hardly believe her ears, yet she hastened toward the side door where Brenda was waiting. The latter glanced down at a forlorn little figure in the scant, green plaid gown, which, although faded, was clean and whole. Her dingy drab jacket was short-waisted, and her red woollen Tam o' Shanter made her look very childish.

As the two stood there in the doorway two young men whom Brenda knew passed by. They were among the most supercilious of the younger set, and as they raised their hats they looked curiously at Brenda's companion. Brenda, though undisturbed, realized that she and Maggie were standing in a very conspicuous place.

"Come, Maggie," she said, "wouldn't you like a cup of chocolate? I'm going to get one for myself."

The little girl meekly followed her to a restaurant across the street, and when they were seated at an upstairs table near a window Maggie felt as if in some way she had been carried to a palace. There was really nothing palatial in the room, though it was bright and cheerful, with a red carpet that deadened all footfalls. But Maggie herself had never before sat at a little round table in a pleasant room, with a waitress attentive to her. A lunch counter was the only restaurant that she had known, and this was certainly very different. The hot chocolate with whipped cream, and the other dainties ordered for the two, made her half forget her grief for her carelessness. Gradually she lost a little of her shyness, and told Brenda about her work, and about the aunt with whom she lived.

"She wants me to keep that place, for it's one of the best shops in town. But she's awful cross sometimes, and I'm terribly afraid of losing it. You see," she continued, "my fingers seem buttered, and I don't run quick enough when they call. I feel all confused like, for there's so much coming and going. Ah, I wish that I had something else I could do!"

"When did you leave school, Maggie?"

"Oh, I'm a graduate; I'm fifteen past, and I got my diploma last spring. My aunt was good; she thinks girls ought to go to school until they get through the grammar school. She says my mother and me, we've been a great expense, and the funeral cost a lot, so she needs every cent I earn."

Gradually Brenda understood about Maggie, and it seemed to her that she would like to talk with her aunt. Glancing at the little enamelled watch pinned to her coat, she saw that it was nearly four o'clock, and this reminded her that at four she was to walk with Arthur Weston. Hurrying her utmost, she could not keep the appointment. She would much prefer to go home with Maggie.

To think with Brenda was usually to act. So, finding her way to a telephone in the office downstairs, she called up her own house, and was surprised to have Arthur himself answer the call.

"But where are you?" he asked; "why can't you come home?"

"I've something very important to do, and I can walk with you any day."

"Really!"

"Yes, indeed."

"But you shouldn't treat me in this way. I shall rush out to find you."

"You can't do it, so you might as well give it up."

In spite of Arthur's slight protest his voice had its usual jesting tone, but before he could remonstrate further he was cut off, and Brenda had turned back to Maggie.

Though it was but a few months since the announcement of Brenda's engagement to Arthur Weston, these two young people had known each other long enough to have a thorough understanding of each other's character. Brenda knew that Arthur hated to be mystified, and Arthur knew that Brenda was wilful. Yet each at times would cross the other along what might be called the line of greatest resistance.

If Maggie was surprised that her new friend wished to accompany her home she did not show her feeling, and Brenda soon found herself in a car travelling to an unfamiliar part of the city. Near the corner where they left the car was a large building, which Maggie explained was a very popular theatre.

"I love to look at those pictures," said the girl, pointing to the gaudy bill-boards leaning against the wall. "I've only been there once, but I'm going Thanksgiving,—if I don't lose my place."

Her face darkened as she remembered that her prospect for having money to spare at Thanksgiving had greatly lessened this afternoon. Brenda did not like the neighborhood through which they now hastened toward Maggie's home in Turquoise Street. It had not the antiquity of the North End, nor the picturesqueness of the West End. There were too many liquor shops, and the narrow street into which they turned was unattractive. She did not like the appearance of many of the people whom she met, and she felt like clinging to Maggie's hand.

Still, the house itself which Maggie pointed out as the one where she lived looked like a comfortable private house. Indeed, it once had been the dwelling of a well-to-do private family. But inside, its halls were bare of carpets, and not over clean. Evidently it had become a mere tenement-house.

"I wonder what my aunt will say," said Maggie timidly, as they stood at the door of her aunt's rooms.

"We'll know soon;" and even as Brenda spoke Maggie had opened the door, and they stood face to face with a small, sharp-featured woman.

"Goodness me! Maggie, are you sick? What did you come home for? Oh, a lady! Please take a seat, ma'am," and Mrs. McSorley showed her nervousness by vigorously dusting the seat of a chair with the end of her blue-checked apron.

Brenda thanked her for the proffered chair, for she had just climbed two rather steep flights of stairs. She felt a little faint from the effort, and from the odors that she had inhaled on the way up. One tenant had evidently had cabbage for dinner, and another was frying onions for tea. Although Brenda herself could not have told what these strange odors were, they made her uncomfortable. While Maggie was explaining why she had returned home so early, Brenda glanced with interest around the room. It seemed to be a combination of kitchen and sitting-room. Above the large cooking-stove was a shelf of pots and pans, and there was an upholstered rocking-chair in one corner. There were plants in the windows, and a shelf on the wall between them with a loud-ticking clock. Under the shelf stood a table with a red-and-white plaid cotton table-cover. A glass sugar-bowl, a crockery pitcher, and a pile of plates showed that the table was for use as well as for ornament. Through a half-open door Brenda had a glimpse of a bedroom that looked equally neat and clean.

"I'm sure, Miss," said Mrs. McSorley when Brenda had finished her story, "I'm very much obliged to you. Maggie's a dreadful careless girl, and a great trial to me. She'll make it her duty to pay that money back to you."

"Oh, no, indeed, I couldn't think of such a thing; if any one was to blame it was I for buying so delicate a vase. Besides, they shouldn't have a small girl carry things about."

"Oh, no, Miss, it was just Maggie's fault. Her fingers are buttered, and sometimes I don't know what her end will be. I suppose I'll have to put her somewhere so's she can't do no mischief."

At these ominous words Maggie's tears fell again, and Brenda, as she afterward said to Arthur, felt her "heart in her mouth." For Mrs. McSorley, with her arms akimbo, and her high cheek-bones and determined expression looked indeed rather formidable, and Brenda hesitated to suggest what she had in mind for Maggie's benefit.

"I've tried to do my duty by her," continued Mrs. McSorley, "just as I did by her mother, and we gave her a funeral with three carriages after she'd been sick on my hands for two years, and her only my sister-in-law; and I kept Maggie at school till she graduated, and she's got a place in one of the best stores in town on account of that. If she had any faculty she might have kept her place, but if people haven't faculty they haven't anything."

While her aunt was talking Maggie had hung up her things,—the Tam o' Shanter on a hook on the bedroom door and the coat on another hook in the corner. Brenda, watching her, thought that her orderliness might prove an offset for her buttered fingers.

Though there was little emotion on Mrs. McSorley's rather hard-featured face, she looked at her visitor with curiosity. She was so pretty, with her slight, graceful figure, waving dark hair, and the friendly expression in her bright eyes was likely to win even so stolid a person as Mrs. McSorley.

"She dresses plain and neat," said Maggie, after Brenda had left; "but she must be awful rich to wear a diamond pin to fasten her watch to the outside of her coat, and there was about a dozen silver things dangling from her belt."

Yet though Brenda made a good impression on Mrs. McSorley, the latter would not commit herself to say just what she would have Maggie do if she should lose her place. She'd set her mind on having the girl rise through the different grades. "I hate to have to switch my mind round—I'm that set," she had explained, adding, "Maggie thinks me stingy because I take all her earnings instead of letting her spend money for fine feathers and theatres like the rest of the girls hereabouts. But some time she'll be grateful." Then came Brenda's opportunity for saying a little about her plan for Maggie,—a plan so quickly made, so likely to be set aside by the grim aunt.

While Mrs. McSorley listened she moved around the room, filling the tea-kettle, lighting the lamp. At last, when Brenda had finished, her reply gave only a slight hope that she would agree to the plan. Yet Brenda felt that she had gained a point when Mrs. McSorley promised to go with Maggie in a few days to visit the school.

The lighted lamp reminded Brenda that outside it must be dusk. It would trouble her to find her way to the cars through unfamiliar streets, and she was only too glad to accept Maggie's offer to guide her, and Maggie was more than delighted to have this last chance for a little talk with "the kind young lady."

"You'll not cry," said Brenda, "even if they won't take you back; remember that you have a new friend."

"Oh, Miss, you're so good, and to think that you have nothing for your twenty dollars but those pieces of broken glass."

"Ah! it's very pretty glass," responded Brenda, "and I'm going to keep the pieces as a reminder."

What she meant was that she would keep the pieces as a reminder not to be extravagant, and as she looked at the little silver mesh purse hanging at her belt she smiled to think that since she left home in the early afternoon it had been emptied of more than twenty dollars, while she had nothing to show for the money,—nothing, indeed, except her new acquaintance with Mrs. McSorley and Maggie, and some fragments of glass.

II

A FAMILY COUNCIL

Brenda had to change from the surface car to one that would take her home through the subway. It was so late that she involuntarily stepped toward a cab standing on the corner opposite the Common. On second thought she decided to economize, since she had already had an expensive afternoon. After depositing her subway ticket she had to wait a few minutes for her car in a crowd, and some one scrambling for a car pushed some one else against her. Brenda, looking around, saw a handsome black-eyed girl with a dark kerchief pinned over her head.

"Oh, I beg your pardon," she said, with a foreign accent, fumbling in a basket that she carried on her arm.

Later, as the car was emerging into the light of the open space near the Public Garden Brenda's hand went instinctively toward the silver-mesh purse that she wore at her belt. It was not there, though she remembered having taken a coin from it as she bought her car ticket. Though accustomed to losing her little personal possessions, Brenda especially valued this purse, and she set her wits at work to trace the loss. She remembered the little girl with the basket, and recalled that the moment before the child had begged her pardon she had felt something jerk her belt. Had she only put the two things together earlier she might have recovered the purse; for of course the child had taken it. Yet to prove this would have been difficult. She would never have had the courage to call a policeman, and remembering the little girl's large, soft eyes, she found it hard to believe her a thief. "An expensive afternoon!" she said to herself. "My twenty dollars gone in one crash, and then that pretty purse with two or three dollars more. What will they say when I tell them at home?"

Then she decided to say nothing about losing the purse. This was the kind of thing that they expected her to do, and her brother-in-law would tease her unmercifully. But Brenda was not secretive, and it was easy enough to speak about Maggie and the broken vase. The story did not lose by her telling, especially as the box with the broken pieces arrived when she was in the midst of her tale. The family was seated in the library after dinner, and each one begged for a little piece of the iridescent glass as a souvenir. But Brenda refused the request, on the plea that for the present she wished to have something to show for her money.

"Although even without the vase I feel that I've gained something," she concluded.

"Experience?" queried her father; "I always hoped you'd feel that experience is a treasure."

"Of course," responded Brenda, "but I was thinking of Maggie McSorley; she may prove of more worth than twenty dollars if she becomes my candidate for Julia's school,—a perfect bargain, in fact."

"If she keeps her promise—"

"If! why, Mamma, I am sure that she will."

"Speaking of losing," interposed Agnes, Brenda's sister, "Arthur lost his temper to-day when he found that you were so ready to break your appointment."

"Oh, he'll find it soon enough; besides, he can't expect me always to be ready to do just what he wishes."

"Well, this involved some one else. He had promised young Halstead to take you to his studio to see a picture, and he was greatly disappointed, for the picture is to be sent away to-morrow."

"There!" exclaimed Brenda, "why didn't I remember? I thought that we were simply going for a walk to Brookline, but they shut off the telephone, or cut me off, and that was why he couldn't remind me. I'm awfully sorry."

"You won't have a chance to tell him so this evening. What shall I say when I see him?"

"You needn't take the trouble, Ralph," replied Brenda; "we're to ride to-morrow, and I can explain."

"It will be his turn to forget."

But Brenda did not heed Ralph's teasing, for already at the sound of three sharp peals of the door-bell she had rushed out to meet her cousin Julia.

"Oh, Julia, I have found just the girl for your school; she is an orphan and hates study, and—"

"Well, upon my word!" exclaimed Ralph, "those are certainly fine qualifications,—'an orphan and hates study'!"

"I understand what she means, or thinks she means," responded Julia, as she laughingly advanced to the centre of the room, greeting the family cordially, while Agnes helped her remove her hat and coat.

"You've come for a week, I hope," exclaimed her uncle, kissing her.

"Oh, I shall be here several times in the course of the week, and I shall stay now overnight. But a whole week away from my work! Ah! Uncle Robert, you're a good business man, to suggest such a thing!" And, seating herself on the arm of Mr. Barlow's chair, Julia shook her finger playfully in his face.

"When do you have your house-warming?" asked Agnes, taking up the bit of sewing that she had dropped on Julia's entrance.

"We are not to have a house-warming, but later we shall invite you one by one, or perhaps two by two, to see the house."

"I suppose you've taken out all the good furniture, and in a certain way the Du Launy Mansion must be greatly changed."

"Don't speak so sadly, Aunt Anna; it is changed, and yet it is not changed. But I did not know that you were attached to the old house?"

"Hardly attached, Julia, for I was there only once, when I called on Madame Du Launy the year before her death. But in its style of architecture and its furnishings it seemed so completely an old-time house that I regret that it has had to be changed into an institution."

"Oh, no, please, Aunt Anna, not an institution; anything but that. Why, we mean to make it a real home, so that girls who haven't homes of their own will feel perfectly happy. Of course we have had to make some changes in the house itself, and remove some of the furniture, but when you visit us you will see that it is far removed from an institution."

"How many nationalities have you now, Julia? You had a dozen or two waiting admittance when you were last here, had you not?"

"There are to be only ten girls in the home, and there are still some vacancies. Indeed you are a tease, Uncle Robert."

Yet, although her uncle and aunt had teased her a little, Julia was not disconcerted, and when Agnes asked her to tell them something about the girls already in residence, she entered upon the task with great good-will.

"Well, first of all, Concetta. It's fair to speak of her first, because she's Miss South's protégée. She is the genuine Italian type, with the most perfectly oval cheeks, and a kind of peach bloom showing through the brown, and her hair closely plaited and wound round and round, and the largest brown eyes. Miss South became interested in her last year when she was visiting schools. She found that her father meant to take her out of school this year to become a chocolate dipper."

"A chocolate dipper! I've heard of tin dippers,—but—"

"Hush, Ralph, you are too literal."

"Yes," continued Julia, "a chocolate dipper. You know there's an enormous candy factory there on the water front, and most of the girls think their fortunes made when they can work in it. But after Miss South had visited Concetta a few times she thought her capable of something better, and so she is to have her chance at the Mansion. But her uncle Luigi was determined to make Concetta a wage-earner as soon as possible. She did not need more schooling, he said.

"Fortunately, however, Concetta has a godmother who, although a working-woman, dingily clad, and apparently hardly able to support herself, is supposed to have money hidden away somewhere. On this account she has much influence in the Zanetti family, and a word from her accomplished more than all our arguments. Concetta is now freed from the dirty, crowded tenement, and I feel that we may be able to make something of her. Then there is Edith's nominee, Gretchen Rosenbaum, whose grandfather is the Blairs' gardener. She's pale and thin, and not at all the typical German maiden. She has a diploma from school of which she is very proud, and she says that she wants to be a housekeeper. The family are very thankful for the chance offered her by the Mansion."

"The Germans know a good thing when they see it, especially if it isn't going to cost them much," said Ralph.

"Then," continued Julia, "there are my two little Portuguese cousins, Luisa and Inez, as alike as two peas in a pod. Angelina told me about them, and their teacher confirmed my opinion that it would be a charity to save them from the slop-work sewing to which their old aunt had destined them."

"How much of an annuity do you have to pay the aunt?" asked Ralph.

Julia blushed, for in fact, in order to give the girls the opportunity that she thought they ought to have at the Mansion, she had had to promise the aunt two dollars a week, which the latter had estimated as her share of their earnings for the next two years. Julia did not wholly approve of the arrangement, although she knew that only in this way could she help the two little girls.

"Hasn't Nora contributed to your household?"

"Oh, yes, the dearest little Irish girl; we can hardly understand a word Nellie says, though she thinks she talks English. Nora ran across her and a party of other immigrants one day when she had gone over to the Cunard wharf to meet some friends. Nellie and a half-dozen others had become separated from the guide who was to take them to their lodging-place in East Boston. They were near the dock, and Nora became very much interested in Nellie. She took her name and destination, and later went to see her, and the result is one of our most promising pupils; that is, we have a chance to teach her more than almost any of the others. But there! I'm ashamed of talking so much shop."

"Oh, no, it's most interesting. You haven't finished?"

"Well, there are two or three other girls, of whom I will tell you more some other time, and there are one or two vacancies. I wish, Brenda, that you could send us a pupil. I'm afraid that you won't have much interest in the school unless you have a girl of your own there."

"But I have—I will—that is—can't you see that I have something very important to tell you?" and thereupon Brenda launched into a glowing account of Maggie McSorley and the prospect of her going to the Mansion. "I just jumped at the idea when it came to me," concluded Brenda, "for I have had so many things on my mind this summer that I didn't make the effort that I had intended to find a girl for you. But now I shall do my utmost to persuade that cross-grained aunt, and I am bound to succeed."

"I wouldn't discourage you, but evidently you made little headway this afternoon," said her mother, "in spite of the pretty high price that you have paid for the pleasure of Maggie's acquaintance."

"Just wait, Mamma; just wait. When I really set out to do a thing I generally succeed. I found out to-day that Mrs. McSorley rather begrudges Maggie her home, although she feels it her duty to keep her. She says that Maggie has a way of upsetting things that is very trying, and she's had to give up to her the little room that she used to keep for a sitting-room. Oh, I'm certain that I can persuade her to spare Maggie."

Then the conversation drifted on to other sides of the work, and Julia's enthusiasm half reconciled Mr. and Mrs. Barlow to the fact that she was to be away from them.

"Home is a career, and we need you more than any group of strange girls possibly can," Mr. Barlow had protested, when Julia had shown him the impossibility of her settling down quietly at home.

"You have Brenda and Agnes. Suppose that I had gone to Europe for two or three years after leaving college. I am sure that then you would not have complained, for you would have thought this a thing for my especial profit and pleasure. Now when I shall be so near that you will see me at least once a week, you are not altogether pleased, because you think that I am likely to work too hard."

"Oh, papa needn't worry," cried Brenda; "I shall see that you have enough frivolity. You shall not overwork the poor little girls either. I feel sorry for them now, with you and Pamela and Miss South egging them on. But I have various frivolities in mind, and you must encourage me."

"I never knew you to need encouragement in frivolity. A little discouragement would be more likely to have a wholesome effect."

Thus they chatted, and Mr. Barlow, looking up from his evening paper from time to time, was convinced that Julia's new interests had certainly not yet taken away her taste for the lighter side of life.

Indeed, on the whole, he had no decided objection to the scheme that Julia and Miss South had started to carry out. As his niece's tastes so evidently ran in philanthropic directions, he knew that in the end she must be happiest when following her bent.

Miss South herself would have been the last to claim originality for the much-discussed school. There were other social settlements in the city, and one or two other domestic science schools in which girls had a good chance to learn cooking and other branches of household work. Yet the school at the Mansion had an object all its own. Miss South felt that each year many young girls drifted into shop or factory who might be encouraged to a higher ambition. For many of them evidently thought first of the money they could immediately earn, and there was no one to suggest that if they prepared themselves for something better they would later have more money as well as greater honor. So she tried to find girls willing to spend two years at the Mansion, while she watched them and advised them and guided them into what she believed would be the best avenue of employment for them. Some people thought that she meant to train all the girls to be domestics; others thought she aimed to keep them out of this occupation. She meant to train them all in housework so thoroughly, that, whether they entered service or had homes of their own, they should be able to do their work properly. She meant, if any of these girls showed special talents, to encourage them to pursue their natural bent.

"Would you let them study art or music?" some one had asked in surprise.

"Yes; why not?"

"Why, girls from the tenement districts!—it doesn't seem right to encourage them in this way."

"Oughtn't any young thing to be encouraged to follow its natural bent? It's a case of individuals, not of sections of the city."

"I've always been sorry," explained Miss South, "for the bright girls who drop out of school at fourteen that their ablebodied parents may snatch the little wages they can earn in the factories. The ten or twelve girls we may have here at the Mansion are very few compared with the hundreds who need the same kind of chance. But I am hoping that through these a broader influence may be exerted."

Although many critics naturally thought that Miss South did wrong in giving girls of a certain class ideas above their sphere, on the whole she was commended for undertaking a good work. There were some also who pitied Mrs. Barlow on account of Julia's partnership in the scheme.

"This is what comes of letting a girl go to college," and they wondered that Mrs. Barlow herself did not express more disapproval.

"You'll have only orphans," said Mr. Elton, a cousin of Mrs. Barlow's, who took much interest in the work; "for in my experience fathers and mothers of the working class are just lying in wait for the earnings of their half-grown daughters. To fill your school you will either have to kill off a few fathers and mothers, or else consider only orphans to be suitable candidates. To be sure, you might offer heavy bribes to parents. But of course you can get the orphans easily, if they have cruel aunts or stepmothers."

"As to cruel aunts," responded Julia, "judging from my own experience, as was said of Mrs. Harris, 'I don't believe there's no sich a person;' and in spite of Ovid and Cinderella, I have my doubts about cruel stepmothers."

"We'll see," said Mr. Elton. "At any rate, you'll have to bribe your girls, and when I meet them my first question will be, How much do they pay you to stay?"

One of the most delightful features in fitting up the house for its new use had been the eagerness to help shown by many of Miss South's former pupils.

Ruth, for example, in furnishing the kitchen, had said, "This will show that I have a practical interest in housekeeping, even though I am to spend my first year of married life in idle travel."

"With your disposition it won't be wholly idle," Miss South had responded.

"Well, I do mean to discover at least one or two new receipts, or better than that, some new articles of food, that I can put at the service of the Mansion upon my return."

"We certainly shall have you in mind whenever we look at these pretty and practical things."

III

BRENDA AT THE MANSION

One fine afternoon, not so very long after she had wasted her twenty dollars and made a friend of Maggie McSorley, Brenda in riding costume opened the front door. As she stood on the top step, somewhat impatiently she snapped her short crop as she gazed anxiously up Beacon Street.

On the steps of the house directly opposite were three girls seated and one standing near by. They were schoolgirls evidently, with short skirts hardly to their ankles, and with hair in long pig-tails. As she looked at them, by one of those swift flights of thought that so often carry us unexpectedly back to the past Brenda was reminded of another bright autumn afternoon, just six years earlier. Then she and Nora, and Edith and Belle, an inseparable quartette, had sat on her front steps discussing the arrival of her unknown cousin, Julia.

How much had happened since that day! Then she had been younger even than those girls across the street, and Julia, who had come and conquered (though not without difficulties) was now a college graduate.

But Brenda was not one to brood over the past, and when one of the girls shouted, "We know whom you're looking for," she had a bright reply ready.

Soon around the corner came the clicking of hoofs on the asphalt pavement. Brenda, shading her eyes from the sun, looked toward the west.

"Late, as usual, Arthur!" she cried, a trifle sharply, as a young man, flinging his reins to the groom on the other horse, ran up the steps toward her.

"Impatient, as usual!" he responded pleasantly, consulting his watch. "As a matter of fact, I'm five minutes ahead of time. But I'd have been here half an hour earlier had I known it was a matter of life and death."

The frown passed from Brenda's face. The two young people mounted their horses, and the groom walked back to the stable.

"Have a good time!" shouted one of the girls, as the two riders started off.

"The same to you!" cried Arthur.

"Ah, me!" exclaimed Brenda, as they rode on, "I feel so old when I look at those Sellers girls. Why, they are almost in long dresses now, and I can remember when they were in baby carriages."

"Well, even I would rather wear a long dress any day than a baby carriage," responded Arthur. "There, look out!" for they were turning a corner, and two or three bicyclists came suddenly upon them. Brenda avoided the bicyclists, crossed the car tracks safely, and soon the two were trotting through the Fenway.

The foliage on the banks of the little stream was brilliant, and here and there were clumps of asters and other late flowers. They rode on in silence, and were well past the chocolate house before either spoke a word.

"Why so silent, fair sister-in-law?"

"Oh, I was only thinking."

"No wonder that you could not speak. I trust that you were thinking of me."

"To be frank," replied Brenda, "that is just what I was not doing. In fact I was thinking of a time when I did not know of your existence."

"Mention not that sad time, mention it not! fair sister-in-law."

When Arthur used this term in addressing Brenda she knew that he was bent on teasing; for although her sister had married Arthur's brother, her engagement to Arthur, announced in June, might very properly be thought to have done away with the teasing title "sister-in-law."

"Don't be silly, Arthur," cried Brenda; "you can't tease me to-day. Several years of my life certainly did pass before I had an idea that you were in the world. I was thinking of the time before we knew each other, when I was so jealous of Julia."

"Jealous of Julia!"

"Oh, I hadn't seen her when I began to have this feeling."

"But why—what made you jealous if you hadn't seen her?

"I can't wholly explain. Perhaps it wasn't altogether jealousy. You see I didn't like the idea of her coming to live with us."

"You must have got over that soon. You and she have always seemed to hit it off pretty well since I've known you."

"Oh, yes, ever since you have known us; and I've always been ashamed of that first year. Though Belle led me on, just a little."

As Arthur still seemed somewhat mystified, Brenda described Julia's first winter in Boston; and she did not spare herself, when she told how she had shut her cousin out from the little circle of "The Four."

"Really, however, Nora and Edith were not at all to blame. They liked Julia from the first. Then what a brick Julia was when she made up that sum of money that I lost after we had worked so hard at the Bazaar for Mrs. Rosa."

Though Arthur had heard more or less about these things before, he enjoyed hearing Brenda narrate them in her quick and somewhat excited fashion.

"Why, you may believe that I really missed Julia when she was at Radcliffe, and I'm fearfully disappointed that she won't be at home with us this winter."

"She isn't going back to Cambridge, is she? I certainly saw her degree, and it was on parchment."

"Oh, Arthur, how you do forget things. I'm sure that I wrote you about the school that she and Miss South were to start."

"I was probably more interested in other things in the letter. But has she lost her money, and hence starts a school?"

"Arthur, I believe that you skip pages and pages."

"No, indeed, dear sister-in-law, but some pages sink more deeply in my mind than others. Has Julia lost her money, and therefore must she teach?"

"You are hopeless, though I believe that really you remember all about it. It's Miss South's scheme. You see she has that great Du Launy house on her hands, and it's a kind of domestic school for poor girls, and Julia is to help her."

"What kind of a school?"

"A domestic school; I think that's it; to teach girls how to keep house and be useful."

"Indeed! Then couldn't you go there for a term or two, Brenda? That kind of knowledge may be very useful to you some time."

Whereupon Brenda urged her horse and was off at a gallop, so distancing Arthur for some seconds before he overtook her. On they went through the Arboretum, and around Franklin Park, then over the Boulevard toward Mattapan and Milton. It was dusk when they turned homeward, and dark, as they looked from a height on the city twinkling below them.

As Arthur left her to take the horses to the stable Brenda called after him, "I may take your advice and enter the school for a year or two."

"We'll see," responded Arthur.

Now, although Brenda had no real intention of entering the new school, either as resident or pupil, she was deeply interested and extremely anxious to see what changes had been made in the Du Launy Mansion, and she was to make her first visit there a day or two after this ride with Arthur Weston.

The school itself was not as new as it seemed. It had existed in Miss South's mind long before she had a prospect of carrying out her plans. Many persons thought it a fine thing for her when she was able to give up her teaching and live a life of leisure in the fine old mansion with Madame Du Launy.

Yet Miss South had wholly enjoyed her work at Miss Crawdon's school, and she had said good-bye to her pupils with regret. Kind though her grandmother was, she had sacrificed more than any one realized in becoming the constant companion of an exacting old lady. Still, as this was the duty that lay nearest her, she devoted herself to it wholly.

Although Madame Du Launy had lived in a large and imposing house, containing much costly furniture, her fortune was smaller than most persons supposed. The larger part of her income came from an annuity that ceased with her death. Miss South had not enough money left to permit her to keep up the great house in the style in which her grandmother had lived; for out of it small incomes were to be paid during their lives to three old servants, and after their deaths this money was to go to Lydia South's brother Louis. To Louis also went the money from the sale of certain pictures and medieval tapestries that the will had ordered to be sold. As to the Mansion itself, Lydia South could do what she liked with it and its contents,—let it, sell it, or live in it.

"She'll have to take boarders, though, if she lives there," said some one; "aside from the expense it would be altogether too dreary for a young woman to live there alone."

But Miss South had no doubt as to what she should do. Here was the chance, that had once seemed so far away, of carrying out her plans for a model school. She found that it was wisest for her to retain the old house for her purpose, as she could neither sell it nor rent it to advantage. The neighborhood was not what it had once been. Almost all the older residents had moved away; two families or more were the rule in most of the houses in the street, and not so very far away were several unmistakable tenement-houses. Miss Crawdon's school had left the street a year or two before, and if she should sell the house no one would buy it for a residence. Julia, who was to be her partner in the new scheme, thought the Du Launy Mansion far better suited to their purpose than any house they could secure elsewhere.

"The North End would be more picturesque, and we could do regular settlement work among those interesting foreigners. But there is more than one settlement down there already, and here we shall have the field almost to ourselves."

Changes and additions to the house had been made during the summer, and not one of Julia's intimates, excepting those who were to live in the Mansion, had been permitted to see it. Nora and Edith and Brenda had implored, Philip had teased, but all had been refused. "You must wait until everything is in readiness."

When, therefore, Brenda and Nora one morning found themselves walking up the little flagged walk to the old Du Launy House, they speculated greatly as to the changes in the house. Outside, on the front at least, there had been no alterations, and everything looked the same as on that morning when the mischievous girls had ventured to pass under the porte-cochère to apologize for breaking a window with their ball. It was the same exterior, and yet not the same. It had, as Brenda said, "a wide-awake look," whereas formerly almost all the blinds had been closed, giving an aspect of dreariness. Now all the shutters were thrown back, blinds were raised, and fresh muslin curtains showed at many windows instead of the heavy draperies of Madame Du Launy's time.

In place of the sleek butler who had seemed like a part of the furnishings, permanent and unremovable, Angelina opened the front door, beaming with satisfaction at the dignity to which she had risen. Indeed she fairly bristled with a sense of her own importance, and answered their questions in her airiest manner.

"Oh, Manuel's doing finely at school, Miss Barlow. I can't be spared much now to go to Shiloh, but I was there over Sunday, and my mother's got two boarders, young women that work in the factory and don't make much trouble for her. So you see I'm not so much needed at home. John's got a place, too, in the city this winter, so that I'll see him sometimes," and Angelina giggled in her rather foolish way.

As she ushered them into the sitting-room Julia emerged from the shadows of the long hall to greet them, and then there was a confusion of sounds, as Nora and Brenda eagerly asked questions at the very moment when Julia was trying to answer them.

"Yes," said Julia, as they sat down in the reception-room, "this is the same room where I first saw Madame Du Launy, the day I took Fidessa home. But you've both been here since?"

"Oh, yes, and I can see that it hasn't been so very greatly changed. There's that picture of Miss South's mother that brought about the reconciliation, as they'd say in a novel," responded Nora gayly. "I'm glad that you haven't made the reception-room as bare as a hospital ward; I had my misgivings, as I approached the door."

"Oh, we wished this to be as pleasant and homelike as possible; you can see that there are many things here that I had in my room at Cambridge," and she pointed to a Turner etching, and a colonial desk, and an easy-chair that Brenda and Nora both recognized.

"The greatest changes," continued Julia, "are in the drawing-rooms;" and leading the way across the hall, Brenda and Nora both exclaimed in wonder. Two drawing-rooms, formerly connected by folding-doors, had been thrown together, and with the partitions removed, the one great room was really imposing.

"You could give a dance here," cried Brenda, pirouetting over the polished floor.

"Who knows?" replied Julia with a smile.

"I'm afraid that you'll have nothing but lectures and classical concerts, and other improving things," rejoined Brenda.

"Who knows?" again responded Julia.

"But it's really lovely," interposed Nora; "I adore this grayish blue paper,—everything looks well with it. And what sweet pictures! why, there's that very water color that Madame Du Launy wanted to buy at the Bazaar. To think that it should come to her house after all! And there's your Botticelli print; well, I believe that it will have an elevating effect; I know that it always makes me feel rather queer to look at it."

"Strange logic!" responded Nora, as they wandered through the large room. "I suppose that you chose the books, Julia; they look like you,—Ruskin, and Longfellow, and Greene's 'Shorter History;' surely you don't expect girls like these to read such books. Why, I haven't read half of them myself; and such good bindings. I really believe that these are your own books."

"Why not? We have had great fun in choosing the books we thought they might like to read from my collections, and from the old-fashioned bookcases in Madame Du Launy's library. The best bindings are her books. Many of them had never been read by any one, I am sure; and as to the covers, we shall see that they are not ill-treated. We have a theory that they may be more attracted by handsomely dressed books; for there's no doubt," turning with a smile toward Miss South, "that they think more of us when arrayed in our best."

"I love these low bookcases," continued Nora; "and I dare say that you'll train them up to liking this Tanagra figurine, and the Winged Victory, and all these other objects that you have arranged so artistically along the top."

"And how you will feel," interposed Brenda, "when some girl in dusting knocks one of these pretty things to the floor. That bit of Tiffany glass, for instance, looks as if made expressly to fall under Maggie McSorley's slippery fingers."

"Oh, that reminds me, Brenda, Maggie has come," said Miss South.

"No; not really?"

"Yes, her aunt brought her over very solemnly two or three days ago. She said she thought it her duty not to trouble you again, as Maggie had already been so much expense to you. She came here the day after you saw her, and I explained our plans, and what we should expect from every girl who entered. She promised that Maggie should stay the two years, and showed a canny Scotch appreciation of the fact, that although Maggie could earn little or nothing while here, at the end of the time she would be worth much more than if she had spent the two years in a shop."

"But how does Maggie feel?"

"Oh, I should judge that resignation is Maggie's chief state of mind. We are going to try to help her acquire some more active qualities," said Miss South.

"Come, come;" Brenda tried to draw Nora from the centre table on which lay many attractive books and periodicals. "I'm very anxious to see Maggie. Can't we see her now, Julia?"

"I believe she's in the kitchen, and as this is one of our most attractive rooms, you might as well go there first."

"The kitchen, you remember, is practically Ruth's gift," said Julia, as they stood on the threshold of a broad sunny room in the new ell, to which they had descended a few steps from the main house. "She paid half the expense of building the ell, and her purse paid for everything in the kitchen."

"But how beautiful; why, it isn't at all like a kitchen!"

"All the same it is a kitchen, though we have tried to make it as pleasant as any room in the house—in its way," concluded Julia smiling.

Advancing a few steps farther, Nora and Brenda continued their exclamations of admiration. The walls, painted a soft yellow, reflected the sunshine, without making a glare. The oiled hardwood floor had its centre covered with a large square of a substance resembling oilcloth, yet softer. A large space around the range was of brick tiles. The iron sink stood on four iron legs with a clear, open space beneath it; there were no wooden closets under it to harbor musty cloths and half-cleaned kettles, and serve as a breeding place for all kinds of microbes. A shelf beside the sink was so sloped that dishes placed there would quickly drain off before drying. The wall above the sink was of blue and white Dutch tiles, and between the sink and the range a zinc-covered table offered a suitable resting-place for hot kettles and pans. Below the clock shelf was another, with a row of books that closer inspection showed to be cook-books. All these details could not, of course, be taken in at once, although the pleasant impression was immediate.

"Plants in the window, and what a curious wire netting!" cried Brenda.

"Yes, it is neater than curtains, keeps out flies, and though it is so made that outsiders cannot look into the room it does not obscure the light. The shades at the top can be pulled down when we really need to darken the room."

Nora stood enraptured before the tall dresser with its store of dishes and jelly moulds, then she gazed into the long, light pantry, the shelves of which were laden with materials for cooking in jars and tins and little boxes, all neatly labelled and within easy reach. On the wall were several charts—one showing the different cuts of beef and lamb, another by figures and diagrams giving the different nutritive values of different articles of food. On the walls were here and there hung various sets of maxims or rules neatly framed, among which, perhaps the most conspicuous, was:

"II. Keep everything in its proper place.

"III. Put everything to its proper use."

IV

AN EXPLORING TOUR

Examining and admiring everything in the kitchen, the girls had half forgotten Maggie, until the sound of singing attracted their attention.

"'Hold the Fort,'" exclaimed Brenda; then, after listening a moment, "But no, the words sound strange."

"Oh, it's one of their work songs," said Miss South, and listening again, they made it out.

Pile up every plate,

Shake the cloth, and then with neatness

Fold exactly straight.

Quick, but silent, every motion

Taking things away,

To the pantry, to the kitchen,

With a little tray."

"Their song betrays them," said Miss South; "this part of the work should have been done earlier," and pushing open the door that led from the other end of the pantry, the four found themselves in the girls' dining-room.

"How is this?" asked Miss South so seriously that one of the young girls holding the table-cloth dropped an end suddenly, and both looked sheepish.

"It was such a lovely day that we went out and sat on the back steps," said one of them frankly, "and then we forgot all about this room."

"But it's the rule, is it not, to put this room in perfect order before you wash the dishes?"

"Yes'm—but we forgot."

"Well, I'm not here to scold, but I only wish that you had been as careful about this as about your kitchen work; I noticed that you had left everything there very neat."

"Yes'm," was the answer from both girls at once.

"Where's Miss Dreen, Concetta?"

"Oh! she said she'd go to market right after breakfast, and leave us do what we could without her."

"I understand," said Miss South, as she introduced each of the young girls to the visitors.

"Miss Dreen, the housekeeper," she explained, as they turned to go upstairs, "supervises the girls in the kitchen. I suppose that she left them alone to test their sense of responsibility. She will require a report on her return."

"Well, if they are as frank with her as with us, she will have little to complain of. One looked like an Italian, and I thought that they were never ready to tell the truth."

"That depends on the girl," said Miss South; "but I have confidence in this one. The other, by the way, is German. Edith's protégée, you remember. I wonder where Maggie is," she continued; "she ought to have been there, for we have three girls together serve a turn in the kitchen each week, and we had her begin to-day."

"I wish that Maggie were as pretty as Concetta," said Brenda, in a tone louder than was really necessary, "for Maggie is mortal plain;" and then, at that moment, she ran into somebody in a turn of the hallway, and when in the same instant the door of an opposite room was opened she saw Maggie McSorley gazing up at her with tear-stained eyes.

"Why, Maggie, I came downstairs expressly to find you. Have you been crying?" A glance had assured her that the tears had not been caused by her hasty words. Indeed, the swollen eyes showed that the child had been crying for some time.

"What is the matter, Maggie?" asked Julia, while Nora and Miss South passed on toward the reception-room. "Miss Barlow has come to see you, and she may think that we have not been kind to you."

"Oh, no, 'm, you've been kind;" and Maggie began to sob after the fashion in which she had sobbed during her first interview with Brenda.

At last by dint of much questioning they found that she and Concetta had disagreed when they first set about clearing the table, and while scuffling a pitcher had been broken.

"I didn't do it—truly; Concetta said I'd surely be sent home in disgrace, and she picked up the pieces to show you, and locked the dining-room door so's I couldn't go back and finish my work, and put the key in her pocket; and what will Miss Dreen say, for it was my day to tidy up the dining-room."

Brenda and Julia saw that they had been rather hasty in forming an opinion of Concetta's innocence and gentleness. They did not doubt Maggie when she showed the swelling on her head, near her cheek-bone, that she said had been caused by a blow.

"Evidently you and Concetta cannot work together at the same time. We'll send Nellie down to the kitchen this week. Now, Brenda, I'll leave you with Maggie for a little while, and she can tell you what she is learning here."

But the interview was far from satisfactory to either of the two. Maggie, always reticent, was now doubly so, as her mind dwelt on the insult she had received from the Italian girl, "dago," as she said to herself. On her part Brenda hated tears, and as she had not witnessed the quarrel, she felt for Maggie less sympathy than when she had seen her weep over the broken vase. Brenda asked a few questions, Maggie replied in monosyllables, and both were relieved when Miss South suggested that Maggie take Brenda up to see her room.

Meanwhile the two young girls in the kitchen were engaged in an animated discussion. In Brenda's presence Concetta's great, dark eyes had expressed intense admiration for the slender, graceful young woman flitting about with pleased exclamations for everything that she saw.

"Ain't she stylish?" Concetta said to her companion as the visitors turned away, "with all them silver things jingling from her belt, and such shiny shoes. Say! don't you think those were silk flowers on her hat?"

Concetta had not been able to give to her English the polish of her native tongue, and the grammar acquired in her teacher's presence slipped away under the influence of the many-tongued neighborhood where she lived.

"She's a great sight handsomer than that Miss Blair," and she looked at her companion narrowly.

"Yes, I wish she'd brought me here instead of Miss Blair; she seems so lively, and Miss Blair is so—so kind of slow."

Gretchen knew very well that she was wrong in speaking thus of the one whose interest had made her an inmate of the delightful Mansion, yet as she and her companion continued to talk Brenda gained constantly at the expense of Edith.

It not infrequently happens that those persons whom we ought to admire the most are those whom we find it the hardest to admire, sometimes even to like. Gretchen owed everything to Edith, who had been very kind to her at a time when her family were in rather sore straits. But appearances count for more than they should with many young persons. Whatever Edith wore was in good taste, and costly, even when lacking in the indefinite something called style. Nora the girls would have put in the same class with Brenda, as quite worthy for them to copy when they should be old enough to dress like young ladies. They did not know that Nora's clothes cost far less than Brenda's, and that Edith's dress was usually twice as costly. It was undoubtedly Brenda's brightness of manner and her generally graceful air that they translated into "stylishness"—the kind of thing that they thought they could make their own by imitation and practice when they were older.

Now it happened that neither Concetta nor Gretchen had the least idea that Maggie was Brenda's special protégée. Had they known this their tongues might have flown even faster, as they jeered at the absent Maggie for being a regular cry-baby. Their own wrongdoing in teasing Maggie sat lightly on their little shoulders. It was their theory that might makes right, and as they had been able to get rid of the girl they didn't like, they believed themselves evidently much better than she.

With her rather listless guide Brenda made the tour of the upper stories. There were twelve pretty bedrooms for the girls, of almost uniform size, although varying somewhat in shape. The furniture in each was the same, but to allow a little scope for individual taste each girl was permitted to decide upon the color to be used in draperies, counterpane, and china. Blue and pink were the prevailing choice, for the range of colors suitable for these purposes is limited. Nellie asked for green, and had it even to the green clover-leaf on the china; and another girl begged for plain white, unwilling to have even a touch of gilt on the china; "it makes me think of heaven," she confided to Julia, "to see everything so white and still when I come up to my room at night."

Maggie had chosen brown for her room, a choice that had especially awakened the ridicule of Luisa, who had said that if she could have her own way there should be a mixture of red, yellow, and blue on all her possessions.

"Why, it's ever so pretty, Maggie," said Brenda, "and you are keeping it neat; but I can't say that those broad brown ribbons tying up the window curtains are cheerful, and I never did like a brown pattern on crockery-ware; but still if you like it—"

"Well, I don't like it quite as much as I expected."

"Then perhaps later you can make some changes; I would certainly have blue ribbons."

"Oh, I don't know, Miss Barlow, there's so many other colors, and I can't tell which I'd like the best."

"I must send you two or three books for your bookshelf."

"Thank you, Miss Barlow," said Maggie coldly, without suggesting, as Brenda hoped she might, some book that she particularly wished to own.

Just then, to her relief, Julia passed through the hall.

"Come upstairs with me and I will show you the gymnasium that we have had built. Edith, you know, paid for it all."

So up to the top of the house the two cousins climbed, followed by Nora and Maggie. Two large rooms had been thrown into one, and as the roof was flat, a fine, large hall was the result. This was fitted up with light gymnastic apparatus, and Julia explained that a teacher was to come once a week to teach the girls. "In stormy weather, when we can't go out, this will be a grand place for bean-bags and similar games, and, indeed, I think that the gymnasium will prove one of the most attractive rooms in the Mansion."

At this moment a Chinese gong resounded through the house.

"Twelve o'clock; it seems hardly possible!" and Julia led the way for the others to follow her downstairs.

From the school-room above three or four girls now appeared, and others came from various parts of the house where they had been at work, among them Concetta and Gretchen.

"Let me count you," said Miss South, after they were seated; "although I can make only nine, I cannot decide who is missing."

As Concetta raised her hand Gretchen tried to pull it down.

"You're not in school; she don't want you to do that."

But the former continued to shake her hand, until Miss South noticed her.

"Please, 'm, it's Mary Murphy; she told me she was going to sneak home after breakfast. Her mother said she didn't sleep a wink for two nights thinking of her dear daughter in such a place; so's soon as she'd read the letter she said she'd go right home."

"Very well," said Miss South, "I'm much obliged to you for telling me;" and then, to the disappointment of all, she made no further comment on Mary Murphy's departure.

The half-hour in the library passed quickly. Each girl reported what she had done thus far, and in some cases Miss South gave instructions for the rest of the day. One or two had special questions to ask, one or two had grievances. Promptly at half-past twelve Miss South gave the signal, and they filed away to prepare for dinner.

"It's a kind of dress inspection. You will understand what I mean if you have ever visited an army post."

"You did not find much fault."

"No, Nora, but I observed many things, and before night I shall have a chance for private conversation with several who stand in special need of it. There were Concetta's finger-nails, and Luisa's shoestrings, and Gretchen had her apron fastened with a safety-pin. Ah! well, we can't expect too much."

"They really are very funny," interposed Julia. "The other day I heard Inez talking to Haleema as they were making a bed: 'Ain't it silly to have to put all these sheets and things on so straight every day when they get all mussed up at night.'

"'My mother never used to make the beds,' said Haleema reminiscently.

"'No, nor mine; we used just to lump them all at the foot of the bed, and pile the blankets from the children's bed on the floor.'

"'It would be nice and handy to hang them over the foot here.'

"'Yes, they'd get so well aired, and it would save all this bother.'

"I'm almost sure that they would have tried this plan," continued Julia, "had they not seen me standing in the hall. However, Haleema did venture to say that she wondered why we insist on having the bureau drawers shut, after they've all been put in good order. It's only when they have nothing in them that she thinks that they should be closed. She also prefers to use the chair in her room for some of the little ornaments that she brought from home, and when she sits down she crouches on the rug."

"Sits Turkish fashion, I suppose you mean."

"Perhaps it is Turkish fashion, although I imagine that there is no love lost between the Syrians and the Turks."

"Haleema is much neater than Luisa, and although we think of her as less civilized, she hasn't half as much objection to taking the daily bath that Luisa considers a perfect waste of time."

"It's very discouraging," said Julia with a sigh.

"Oh, one needn't mind a little thing like that. One or two that I could mention think it a great waste of time to wash the dishes after every meal."

"Ugh!" and an expression of disgust crossed Brenda's face at the mere thought of using the same plates and cups unwashed for a second meal.

"There's a slight strain on the one who supervises their table manners. I've just been through my week. You see," and she turned in explanation toward Nora and Brenda, "each resident serves for a week as head of the girls' table at breakfast, and it is her duty to correct all their little faults as a mother would. At the other two meals they have only Miss Dreen, for we think that they ought to be free from the restraint of our presence at these other meals."

"Do you try to guide conversation, too?"

"Oh, yes, but thus far our presence has seemed a decided damper, and the solemnity of breakfast is in great contrast with the hilarity at the other two meals. At tea-time their laughter sometimes reaches even as far as the library."

"They are ready to learn, and particularly ready to imitate. I am really obliged to watch myself constantly," said Julia, "lest I say or do something that may return against me some time, like a boomerang."

"Then I fear that I should be a poor kind of resident," rejoined Brenda, "for it has been said that I speak first and think afterwards. However, in the presence of Maggie McSorley I am always going to try to do my best; for apparently it's my duty to bring her up for the next few years, and I won't shirk. But I wish that it had been Concetta instead of Maggie on whom I stumbled. I'm going to tell Ralph that I've found a perfect model for his new picture. Wouldn't you let her pose?"

"Ask Miss South," responded Julia.

But Miss South, without waiting for the question, only shook her head, with an emphatic "No, indeed."