The army behind the army

E. Alexander Powell

BY E. ALEXANDER POWELL

- THE ARMY BEHIND THE ARMY

- THE LAST FRONTIER

- GENTLEMEN ROVERS

- THE END OF THE TRAIL

- FIGHTING IN FLANDERS

- THE ROAD TO GLORY

- VIVE LA FRANCE!

- ITALY AT WAR

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

THE ARMY

BEHIND THE ARMY

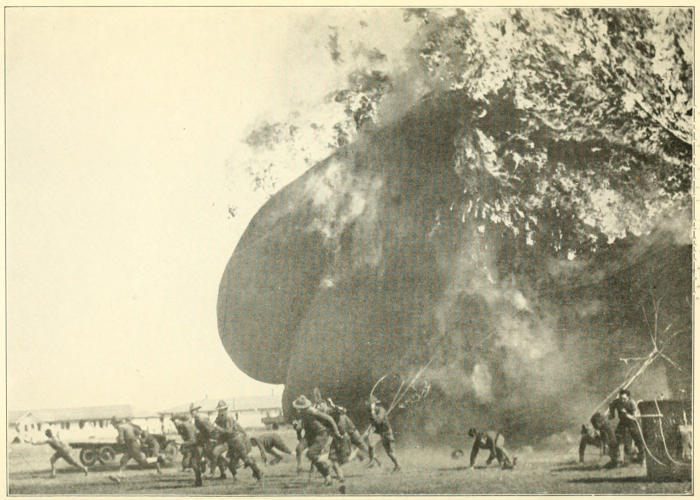

THE BURNING OF AN OBSERVATION BALLOON AT FORT SILL, OKLAHOMA.

THE ARMY

BEHIND THE ARMY

BY

MAJOR E. ALEXANDER POWELL

U. S. A.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1919

Copyright, 1919, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published September, 1919

TO

FIVE FRIENDS OF THE A. E. F.

LIEUT.-COL. N. J. WILEY

MAJOR HUGH B. ROWLAND

MAJOR HAMILTON FISH, JR.

LIEUT. WILFORD S. CONROW

LIEUT. KINGDON GOULD

IN MEMORY OF THE DAYS WE SPENT TOGETHER

ON THE BANKS OF THE MARNE

AN ACKNOWLEDGMENT

For the interest they have shown and the assistance they have given me in the preparation of this book, I am indebted to many persons. Each chapter was written with the co-operation of the chief and subchiefs of the branch of the army with which it deals, and upon its completion it was by them carefully read and revised. The statements and figures are as nearly accurate, therefore, as extreme care can make them. The Honorable Newton D. Baker, Secretary of War, authorized the writing of the book and issued orders that every facility was to be afforded me for obtaining the necessary material, and the Honorable Benedict Crowell, Assistant Secretary of War, who from the beginning took a lively personal interest in the work, placed at my disposal the great mass of material which he had collected for his Official Report. To Major-General William S. Seibert, Director of the Chemical Warfare Service, to Colonel William S. Walker, in command of Edgewood Arsenal, and to Colonel Bradley Dewey, in command of the Gas Defense Division, I am particularly indebted, as it was due to their efforts that I was able to undertake the writing of the book. Major-General William M. Black, Chief of Engineers, Lieutenant-Colonel Chenoweth, and Major Evarts Tracy of the Corps of Engineers; Major-General C. T. Menoher, Director of Military Aeronautics, Colonel S. M. Davis, Lieutenant-Colonel H. B. Hersey, and Major H. M. Hickam of the Air Service; Colonel James L. Walsh, to whose generosity I am indebted for much of the material relating to Army Ordnance, Colonel E. M. Shinkle and Major A. B. Quinton, Jr., of the Ordnance Department; Major-General George S. Squier, Chief Signal Officer of the Army, Brigadier-General C. McK. Saltzman and Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph O. Mauborgne of the Signal Corps; Major-General M. W. Ireland, Surgeon-General, and Colonel M. A. De Laney of the Medical Corps; Brigadier-General Marlborough Churchill, Director of Military Intelligence, Captain R. G. Martin, Captain A. R. Townsend, Captain H. M. Dargan, and Captain J. Stanley Moore, of the Military Intelligence Division; Major-General Rogers, Quartermaster-General of the Army; Colonel I. C. Welborn, Director of the Tank Corps; Brigadier-General Drake, Director of the Motor Transport Corps; Captain W. K. Wheatley, Chief of the Historical Section of the Motor Transport Corps, and W. L. Pollard, Esq., Chief of the Historical Branch of Purchase and Storage, all showed me exceptional courtesy and afforded me every possible assistance. I welcome this opportunity to express to them my appreciation. To the Bulletin of the Spruce Production Division, published by the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen, I am indebted for a considerable portion of the account of spruce production in the Pacific Northwest.

E. Alexander Powell.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| The Ears of the Army | 1 |

| “Essayons” | 47 |

| The Gas-Makers | 101 |

| The “Q. M. C.” | 140 |

| Ordnance | 197 |

| Fighters of the Sky | 259 |

| “M. I.” | 328 |

| “Treat ’em Rough” | 409 |

| “Get There!” | 424 |

| Menders of Men | 437 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| The Burning of an Observation Balloon at Fort Sill, Oklahoma | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

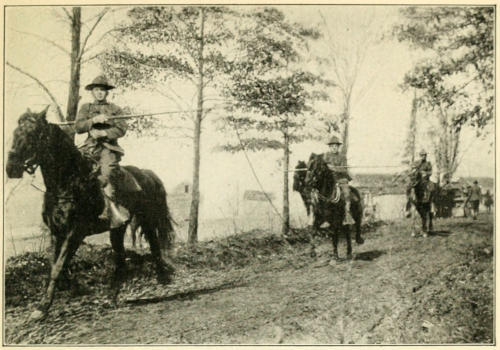

| Laying a Field Telegraph Line | 8 |

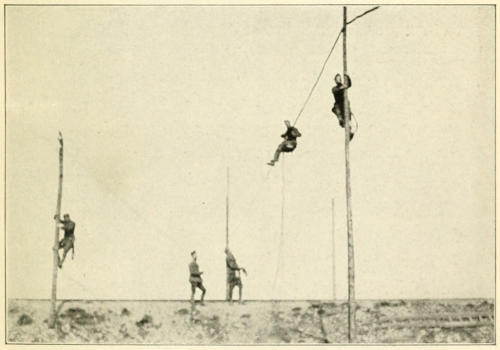

| Signal-Corps Men Erecting a Field Telephone | 8 |

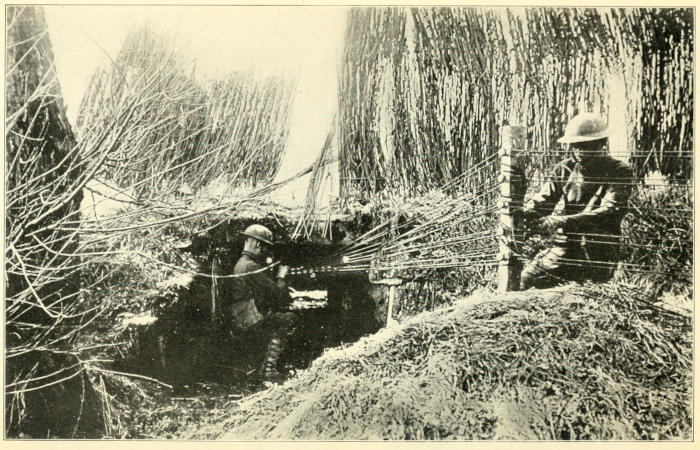

| Signal-Corps Men at Work Repairing the Tangle of Copper Wires Which Link the Infantry in the Front-Line Trenches with the Guns | 9 |

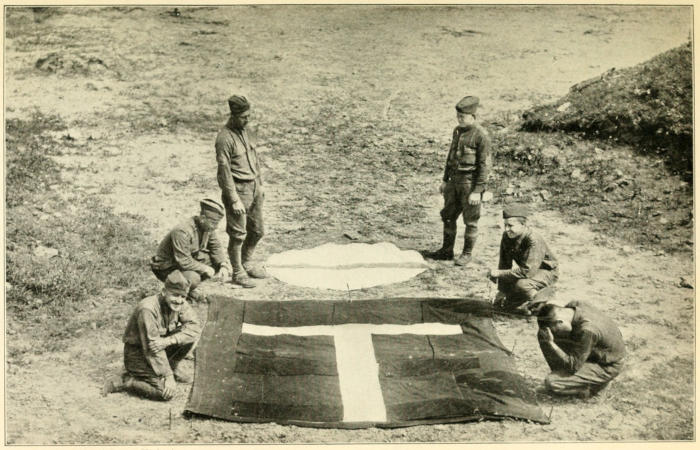

| Communication by Use of Panels | 14 |

| A Member of the Signal Corps Sending Messages by Means of a Lamp | 15 |

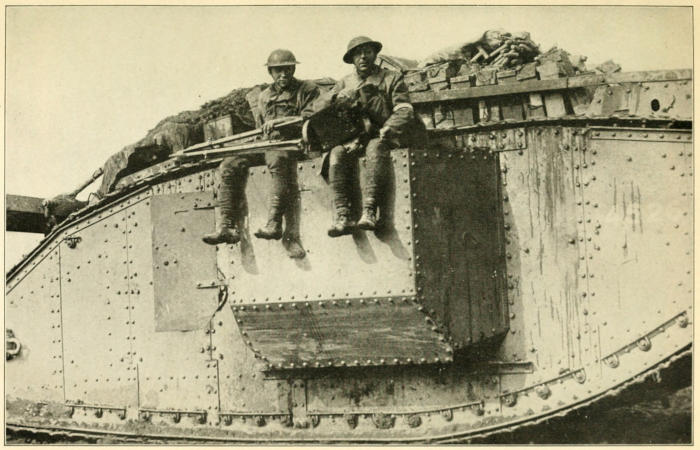

| Motion-Picture Operators of the Photographic Section of the Signal Corps Going into Action on a Tank | 34 |

| An Officer of the Signal Corps Operating a Telephone at the Front | 35 |

| New Type of Search-Light Used in the American Army | 80 |

| Camouflaging a Divisional Headquarters in the Toul Sector | 81 |

| Suits Known as Cagoules | 94 |

| The Work of the Camouflage Corps | 95 |

| Man and Horse Completely Protected Against Poisonous Gas | 132 |

| Types of Gas Masks Used by American and European Armies | 133 |

| 1,500 Tons of Peach-Pits Used for the Manufacture of Charcoal for Use in Gas Masks | 134 |

| Testing Respirators Outside the Gas Chamber | 135 |

| Testing Gas Masks Inside the Gas Chamber | 135 |

| Advancing Under Gas | 138 |

| Training for Gas Warfare | 139 |

| Cutting Their Way through Barbed-Wire Entanglements while Training with Gas Masks | 139 |

| American Salvage Dump in France | 192 |

| A Workroom in an American Salvage Depot in France | 192 |

| An American Delousing Station | 193 |

| An American Laundry in Operation Near the Front | 193 |

| A 16-Inch Howitzer | 202 |

| A 16-Inch Howitzer on a Railway Mount | 203 |

| A Scene in an American Arsenal | 214 |

| Filling a Powder-Bag for a 16-Inch Gun | 215 |

| An American 75-mm in Action | 232 |

| The 37-mm Gun in Action | 233 |

| An American 75-mm Field Gun, Tractor Mounted | 234 |

| A 12-Inch Railway Gun in Operation | 235 |

| A 12-Inch Seacoast Mortar on a Railway Mount | 236 |

| 6-Inch Seacoast Rifles Taken from Coast Fortifications and Mounted for Field Use in France | 237 |

| John M Browning, the Inventor of the Pistol, Rifle, and Machine Gun Which Bears His Name | 242 |

| The Browning Heavy Machine Gun | 242 |

| A Rifle Grenadier | 243 |

| Bombing Practice | 288 |

| Eggs of Death | 288 |

| Pigeons Have Been Repeatedly Used with Success from Both Airplanes and Balloons | 289 |

| The Eye in the Sky; an Airplane Camera in Operation | 289 |

| Radio Telephone Apparatus in Operation on an Airplane | 300 |

| President Wilson Talking with an Aviator in the Clouds by Means of the Radio Telephone | 300 |

| A Range-Finder for Ascertaining the Altitude and Speed of Airplanes | 301 |

| A Sentinel of the Skies | 306 |

| An American Observation Balloon Leaving Its “Bed” Behind the Western Front | 307 |

| A Balloon Company Manœuvring a Caquot from Winch Position to Its Bed | 307 |

| An American Kite Balloon About to Ascend | 310 |

| Planes in Battle Formation | 311 |

| A Basket Parachute Drop | 316 |

| Balloonist Making a Parachute Jump from an Altitude of 7,900 Feet | 316 |

| Training the Student Aviator | 317 |

| The American Whippet Tank | 418 |

| The Mark V Tank | 418 |

| A Squadron of Whippet Tanks Advancing in Battle Formation | 419 |

| A Squadron of Whippet Tanks Parked and Camouflaged to Conceal Them from Enemy Observation | 419 |

| Mobile Machine-Shop Operating in a Village Under Shell Fire | 434 |

| Supply of Motor Tires | 434 |

| A Motor-Car Wrecked Returning from the Front Lines | 435 |

| Field-Hospital | 454 |

| An Infectious Ward | 454 |

| Clear, Filtered, Disinfected Water | 455 |

| Water Station on the Western Front | 455 |

THE ARMY

BEHIND THE ARMY

I

THE EARS OF THE ARMY

Before the war made most Americans as conversant with the functions of the various branches of the army as they are with the duties of the gardener and the cook, the work of the Signal Corps troops was popularly supposed to consist, in the main, of standing in full view of the enemy and frantically waving little red-and-white flags. Don’t you remember those gaudily colored recruiting posters which depicted a slender youth in khaki standing on a parapet, a signal-flag in either outstretched hand, in superb defiance of the shells which were bursting all about him? This popular and picturesque conception was still further fostered at the officers’ training-camps, where the harassed candidates spent many unhappy hours attempting to master the technic of semaphore and wig-wag. Yet, as a matter of fact, during more than four years of war I do not recall ever having seen a soldier of any nation attempt to signal by means of flags, save, perhaps, in the back areas. Had such an attempt been made under battle conditions the signaler probably would have provided, in the words of the poet, “more work for the undertaker, another little job for the casket-maker.”

By this I do not mean to imply that the changed conditions brought about by the Great War made the army signaler a good life-insurance risk. Far from it! But they did have the effect of making him a trifle less dashing and picturesque. Instead of recklessly exposing himself on the parapet of a trench in order to dash-dot a message which the enemy could have read with the greatest ease, he dragged himself, foot by foot, across the steel-swept terrain, a mud-caked and disreputable figure, on his task of repairing the tangle of copper strands which linked the infantrymen in the front-line trenches with the eager guns; crouching in the meagre shelter afforded by a shell-hole, with receivers strapped to his ears, he sent his radio messages into space; carrying on his back a wicker hamper filled with pigeons, he went forward with the second wave of an attack; or, by means of a military edition of the dictaphone device so familiar to readers of detective stories, he eavesdropped on the enemy’s strictly private conversations. Even though he had no opportunity to wave his little flags, the Signal Corps man never lacked for action and excitement.

If the Air Service is, as it has frequently been termed, “the eyes of the army,” then the Signal Corps constitutes the army’s entire nerve-system. Under the conditions imposed by modern warfare, an army without aviators would be at least partially blind, but without signalers it would be bereft of touch, speech, and hearing. It is the business of the Signal Corps to operate and maintain all the various systems of message transmission—telegraphs, telephones, radios, buzzers, Fullerphones, flags, lamps, panels, heliographs, pyrotechnics, despatch-riders, pigeons, even dogs—which enable the Commander-in-Chief to keep in constant communication with the various units of his army and which permit of those units keeping in touch with each other. It was imperative that General Pershing should be able to pick up his telephone-receiver in his private car, sidetracked hundreds of miles away from the battle-front, perhaps, and talk, if he so desired, with a subaltern of infantry crouching in his dugout on the edge of No Man’s Land. The Secretary of War, seated at his desk in Washington, must be enabled to talk to the commander of a camp on the Rio Grande or of a cantonment in the Far Northwest. Though every strand of wire leading to the advanced positions was cut by the periodic shell-storms, means had to be provided for the commanders of the troops holding those positions to call for artillery support, for reinforcements, for ammunition, or for food. It was essential to the proper working of the great war-machine that the chiefs of the Services of Supply at Tours should be in constant telegraphic and telephonic communication with the officers in charge of the unloading of troops and supplies at Bordeaux and Marseilles, at Brest and St. Nazaire. It was vital that the Chief of Staff should be kept constantly informed of conditions at the various ports of embarkation. All this was made possible by the Signal Corps. But it was also necessary that these various conversations should be so safeguarded that there was no possibility of them being overheard by enemy spies. And the Signal Corps saw to that too.

When Count von Bernstorff was handed his passports in the spring of 1917, the Signal Corps consisted of barely 50 officers and about 2,500 men. When, nineteen months later, the German delegates, standing about a table in Marshal Foch’s private car, sullenly affixed their signatures to the Armistice, the corps had grown to nearly 2,800 officers and upward of 53,000 men. It comprised at the close of the war seventy-one field signal battalions, thirty-four telegraph battalions, twenty replacement and training battalions, and fifty-two service companies, together with several pigeon and army radio companies, a photographic section, and a meteorological section.

Not many people are aware, I imagine, that nearly a third of the officers and men who wore on their collars the little crossed flags of the Signal Corps were recruited from the employees of the two great rival telephone systems of the United States—the Bell and the Independent. The former raised and sent to France twelve complete telegraph battalions; the latter ten field signal battalions—to say nothing of the great number of experts, specialists, and telephone-girls who left the employ of those systems to embark on the Great Adventure. So you need not be surprised if, the next time your telephone gets out of order, your trouble call is answered by a bronzed and wiry youth who wears in the buttonhole of his rather shabby coat the tricolored ribbon of the D. S. C.—won, perhaps, while keeping the communications open at Château-Thierry. And the operator who says, “Number, please,” so sweetly, may have been—who knows?—one of those alert young women in trim blue serge who sat before the switchboard at Great Headquarters and handled the messages of the Commander-in-Chief himself.

For a number of years before the war it was recognized in Washington that should the United States ever become involved in a conflict with a first-class Power, the handful of officers and men who composed the personnel of the Signal Corps would be utterly incapable of handling, unaided, the enormous system of communications which is so essential to the success of a modern army. It was perfectly evident, moreover, that should the country suddenly find itself confronting an emergency, there would be no time to train officers and men in the highly technical requirements of the Signal Corps. To insure the success of the great citizen armies which we would be compelled to raise with the utmost speed in case of war, it was essential that there should be available an adequate supply of men who were already thoroughly trained in the installation and operation of the two chief forms of military communication—telegraphs and telephones. And this trained personnel was at hand in the employees of the great telephone and telegraph companies. It was not, however, until June, 1916, when Congress, tardily awakening to the imminent danger of sparks falling on our own roof from the great conflagration in Europe, passed the National Defense Act, which authorized, among other things, the creation of the Signal Officers’ Reserve Corps and the Signal Enlisted Reserve Corps, that the way was opened for definite action. Shortly thereafter the Bell Telephone System was approached by the Signal Corps with the suggestion that a number of reserve Signal Corps units be recruited from its various subsidiary organizations. The suggestion met with the hearty approval of the Bell officials and the work of organization was turned over to the Bell’s chief engineer, Mr. J. J. Carty, the foremost telephone expert in the world. In accordance with the plans drawn up by Mr. Carty, there were organized from the employees of the New York, New England, Pennsylvania, Chesapeake and Potomac, Central Union, Cincinnati, Northwestern, Southwestern, Southern, Mountain States, and Pacific telephone companies twelve reserve telegraph battalions. I might mention, in passing, that Mr. Carty was given a commission as major, was later promoted to colonel, was made chief of the telegraphs and telephones of the A. E. F., and for his invaluable work was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

While the Bell System was devoting its efforts to the raising of the telegraph battalions, the Chief Signal Officer of the Army asked the co-operation of the Bell’s great rival, the United States Independent Telephone Association, in the organization of a number of field signal battalions for front-line work. Mr. F. B. McKinnon, vice-president of the association, assumed charge of the work and enthusiastically threw himself and all the agencies at his disposal into the business of recruiting, ten field battalions eventually being raised by the Independent System.

But the demand for trained personnel from the telegraph and telephone companies did not end with the formation of the units I have just mentioned. With the declaration of war and the despatch to France of the first American contingents, it was realized that their work had only begun. Though the telegraph and field battalions contained many experts on telegraphy and telephony, they were formed primarily as constructive and operative units for comparatively short lines. But the lines in the A. E. F. did not remain short, and as they grew in length and in number, new equipment and different types of technicians had to be employed. In August, 1917, there came from France the first call for specialists, to include telephone-repeater experts, printer-telegraph mechanicians, printing-telegraph traffic supervisors, and similar highly trained men. Almost at the same time there was received a cablegram from General Pershing requesting the immediate organization in Paris of a Research and Inspection Department, in order that the best, latest, and most reliable signal equipment might be assured for the American troops. To Colonel Carty was assigned the task of selecting the twelve scientists to be the officers of the new division and the fifty enlisted assistants who were necessary to commence the work. He found them in the remarkable Research Department of the Western Electric Company, which is closely allied with the Bell System, Mr. Herbert Shreeve of the Western Electric being given a commission as lieutenant-colonel and placed in charge of the work. The improvements made and the devices introduced by this division made the signal system of the A. E. F. one of the marvels of the war. So wide-spread and reliable were the American communications, and so efficient the American operators, that on more than one occasion Marshal Foch, during his tours of inspection along the battle-front, went many miles out of his way in order to use the American wires for important conversations. But so rapid was the growth of the telegraph and telephone lines in France that hardly had one requisition for additional personnel been filled before another was received. Yet always the great systems of the United States answered the call, and this despite their crying need for such personnel at home, where war conditions had enormously increased their business, and the difficulty which they were experiencing in making replacements in their own forces. In fact, of the 2,800 officers commissioned in the Signal Corps during the war, fully 30 per cent had been trained with the telegraph and telephone systems, and the percentage of enlisted men was equally high. The response made by these great corporations to the nation’s call constitutes, indeed, one of the most gratifying incidents of the war.

When the history of the great conflict comes to be written, the story of the achievements of the telegraph and field battalions of the Signal Corps will form one of its most fascinating chapters. Working under the most trying conditions, in a land with whose customs they were unfamiliar and whose language they did not understand, with equipment and material frequently improvised from whatever was at hand, they covered France from the seaboard to the Rhine with the network of their wires; they made it as easy for Great Headquarters to communicate with a remote outpost in Alsace or the Argonne as it is for a brokerage house in Wall Street to communicate with the manager of its Chicago branch, and it established a standard of speed and efficiency which will make the French dissatisfied with their own services for years to come. Their work was, in the words of General Pershing, “a striking example of the wisdom of placing highly skilled technical men in the places where their experience and skill will count the most.”

LAYING A FIELD TELEGRAPH LINE.

They established a standard of speed and efficiency.

Photograph by Signal Corps, U. S. A.

SIGNAL CORPS MEN ERECTING A FIELD TELEPHONE.

Working under the most trying conditions, these men covered France with the network of wires.

SIGNAL CORPS MEN AT WORK REPAIRING THE TANGLE OF COPPER WIRES WHICH LINK THE INFANTRY IN THE FRONT-LINE TRENCHES WITH THE GUNS.

Despite the unending stream of men which constantly flowed Europeward for work on the “A. E. F. Tel. & Tel. Co.,” as our military telegraphs and telephones were familiarly known, more were ever needed, and it was finally decided, though, I believe, with considerable reluctance on the part of certain old-fashioned officers in the War Department, to replace the men operators, wherever possible, with girls. Again the American systems were called upon, this time to furnish young women who possessed the necessary technical experience, and to give them a working knowledge of French. Imagine the furor of excitement that swept through every telephone-exchange in the country when it was learned that girls were wanted for service in the A. E. F.! Where was the red-blooded, adventure-loving American girl who could resist such a call? Soon the company officials as well as the Signal Corps itself were almost swamped by the flood of applications that poured in. Then the Signal Corps found itself confronted by the necessity of educating the applicants; to do this it had to operate a whole system of boarding-schools for girls. Such schools were established in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco, Jersey City, Atlantic City, and Lancaster, Pa., the candidates for overseas duty being given intensive courses in military telephony, French, and European geography, together with lectures on French manners and customs, and, I might add (this in a whisper), on their own behavior, particular emphasis being laid on the evils of flirting, impertinence, and gum-chewing. Upward of 200 girls were finally selected, provided with uniforms and overseas caps of navy serge—which looked as though they might have been designed by the technical experts of the Signal Corps—and sent to France as full-fledged members of the A. E. F. No pupils at a fashionable girls’ boarding-school were ever more strictly chaperoned. At Tours quarters were built for them on an island in the Loire, which was connected with the mainland by a narrow foot-bridge, the military police on duty at the end of the bridge only permitting the girls to “go ashore” when they were accompanied by a matron or were in pairs. Notwithstanding the strictness of the regulations under which they lived and worked, it was a girl’s own fault if she came home unengaged. Though it goes without saying that the military authorities took every precaution against exposing the girls to danger, those who were on duty in towns near the front, such as Toul, on numerous occasions tasted the excitement of German air-raids, one of them being cited in army orders for remaining at her post and coolly continuing to operate her switchboard “whence all but she had fled.”

I always liked the true story of the telephone-girl who, upon her arrival at an American port of debarkation, informed the landing officer that she was a second lieutenant.

“But why do you call yourself a second lieutenant?” he inquired. “No commissions have been given to telephone-girls.”

“I don’t see what that’s got to do with it,” she retorted, tossing her head. “I get more pay than a second lieutenant, and I’ve been of more use to the army than any second lieutenant that I know.”

In order to assess at their true worth the achievements of the Signal Corps during the war, it is essential to realize the amazing number, variety, and magnitude of the tasks the corps was called upon to perform. The Signal Corps is a staff department charged with providing means of communication for the army, both at home and overseas. According to the present tables of organization, one field signal battalion is usually attached to each division, the telegraph battalions being used as corps or army troops. Generally speaking, the telegraph battalion maintains communications in the rear; the field battalion usually operates with the combat troops at the front. In addition to these troops, there are numerous special units, such as pigeon companies, radio companies, photographic and meteorological sections, which are attached to corps, armies, or to General Headquarters. In France where hundreds of miles separated our base ports from our troops on the firing-line, there devolved upon the Signal Corps an enormous amount of work in the area known as the Services of Supply. The magnitude of the telegraph and telephone systems in the S. O. S. is illustrated by the fact that when the Armistice was signed, the Signal Corps in France was operating 96,000 miles of circuits known as “long lines,” with 282 telephone-exchanges, and a total of nearly 9,000 stations. The requirements for wire in the field were even greater. When our operations were at their height in the summer of 1918, it was estimated that the Signal Corps would require 68,000 miles of “outpost wire” a month for use at the front in connecting telegraph and telephone systems. Outpost wire is, I ought to explain, a development of the war. It is composed of seven fine wires, four of them bronze and three of them of hard carbon steel, stranded together and coated first with rubber, then with cotton yarn, and finally paraffined. This wire is produced in six colors—red, yellow, green, brown, black, and gray—in order that it may readily be identified in the field, the red wire running, for example, to the artillery, the yellow to regimental headquarters, green to brigade headquarters, and so on. The enormous amount of this wire required is explained by the fact that very little of it was saved, it being out of the question to pick it up during the hurry and excitement of an advance, while hundreds of miles of it were destroyed during the heavy bombardments which usually preceded an attack.

Within the memory of many of us the size of combat armies was largely determined by the efficiency and scope of their signal systems, it being essential that the forces in the field should be kept within a size which permitted of communication being maintained between all units by means of runners, riders, or visual signals. Those were the days when messengers, often chosen by lot, crawled through the enemy’s lines at night in order to bring reinforcements to beleaguered garrisons; when stories of ambush and massacre or urgent appeals for ammunition and food were brought to headquarters by weary riders clinging to the manes of reeking ponies; or when, in the Indian country, cavalry columns communicated with each other by means of heliograph messages flashed from mountain-top to mountain-top, or signal-fires curling slowly skyward.

But all this changed with the introduction of the telegraph and the telephone, the communications of an army thereafter being limited only by the amount of its wire. A far greater change came, however, with the introduction of the radio or wireless, whose area of operations is limited only by the power of the sending apparatus. Now it should be kept in mind that each of the systems of military signalling which I have already enumerated—telegraphs, telephones, radios, panels, lamps, flags, pigeons, runners, dogs, and the rest—is an adjunct to the others—when one fails, another is employed to get the message through. If the wires of the field telegraph and telephone are cut by a barrage, the radio is employed; if a shell knocks out the radio set, the message is intrusted to a pigeon; should the pigeon fail, a runner attempts to take it through; and if the runner is killed, the message can be communicated, either by means of rockets or by cloth panels spread upon the ground, to the aviators circling overhead.

Despite the new methods of transmitting messages produced by the war, the telephone remains the backbone of the military signal system. Though the portable telephone instrument used by all front-line troops was manufactured in the United States for commercial purposes prior to the war, the switchboard in most general use by mobile troops was originally developed by the French, being the only telephone equipment used by the American forces which was not of American design. This switchboard, which was built in units so that it could be expanded from four to twelve lines, was the “Central” of the front-line dugout, being so compact that it could be carried as part of the equipment of a soldier and quickly put into operation. For the use of the larger field units there was designed a camp switchboard, with provision for forty wires, which when in transit resembled a commercial traveller’s sample-trunk. A third type of switchboard, for use at headquarters in the zone of combat, but where extreme portability was not essential, was designed in units, like a certain popular style of sectional bookcase, and could readily be increased to any size required. An important auxiliary to the field-telephone lines was the buzzerphone, an American device for use where extraordinary secrecy was imperative, it being impossible for the German Listening-in Service to eavesdrop on messages sent by this method.

COMMUNICATION BY USE OF PANELS.

When other means of communication is found impracticable, the infantry can communicate with aviators by means of panels of cloth cut in various shapes spread upon the ground.

Photograph by Signal Corps, U. S. A.

A MEMBER OF THE SIGNAL CORPS SENDING MESSAGES BY MEANS OF A LAMP.

Prior to the war the “lance-pole” was used exclusively by American troops in the field, as it permitted of rapid line construction and served its purpose admirably in open warfare. The conditions prevailing in Europe made the use of this pole impracticable, however, and where poles were used at all they consisted of very short stakes with special cross-arms, miniature copies, in fact, of the commercial equipment commonly used in the United States. The enormous mileage of the trench-lines called for vast quantities of insulators, cross-arms, and other special fittings, in all of which there was great wastage, for though the instruments used on the military lines usually had a certain degree of protection, the lines themselves were constantly exposed to artillery and airplane bombardment.

A factor which greatly complicated the supply of the front-line forces with wire was the necessity for maintaining two-way or twisted-pair lines in order to avoid giving information to the enemy, for the detectors used in the German listening-posts were so highly developed that a telegraph or telephone message sent over a “grounded” or single-conductor line was to all intents and purposes sent direct to Berlin. This necessity for a double-conductor line relegated the old field-wire of open warfare to the scrap-heap, a long series of experiments being required to produce a twisted-pair wire which was light enough to permit of easy portability and rapid laying, strong enough to stand the strain of heavy traffic and shell-shock, and withal so well insulated that “leaks” to the ground might not reveal to the enemy listeners-in facts intended to be strictly confidential. The enormous demands for all types of wire and cables which came both from the A. E. F. and from our allies necessitated the United States being combed for every foot of available material and the speeding up of production until every wire-mill in America was working twenty-four hours a day. Yet, in spite of labor troubles, housing problems, and the difficulties of obtaining material and transportation, the wire-makers at home filled every requirement of the soldiers overseas.

Of all the varied activities of the Signal Corps, none was more fascinating or mysterious in its operation than the work of the Radio Intelligence Sections, particularly the so-called listening-stations, which, by means of supersensitive receiving and amplifying instruments electrically connected with ground-plates placed as close as possible to the enemy positions, were enabled to overhear the ground-telegraph operations of the Germans and the conversation leaking from defective or non-metallic telephone and telegraph circuits. This remarkable service, some of whose achievements would seem to the layman to verge on the miraculous, combined the discoveries of Ohm, Volta, and Galvani with the methods of LeCoq and Sherlock Holmes. These stations could, of course, operate successfully only under favorable conditions, the chief requisites being that the enemy’s trenches should not be too far away and that the intervening terrain should be free of creeks, gullies, or other features which might sidetrack the currents which it was desired to intercept. The listening-stations were usually situated in the second line of trenches, the ground-plates being placed about 300 yards apart. In order to obtain satisfactory results it was necessary that the ground-plates should be placed as close to the enemy as possible, the work of installing them, almost under the noses of the Huns, being one of the most hazardous duties which the signal troops were called upon to perform. The men operating the listening-stations had to remain on duty for a week at a time—a considerably longer tour of duty than was required, under ordinary conditions, of the infantrymen. They were expected to possess a fluent knowledge of German and to be able to both speak and understand it as well as they did English, though this requirement was not always fulfilled toward the end. They were thoroughly coached, moreover, in German military phrases and colloquialisms and had to be proficient in recording ground-telegraphy code, which, though slow, is extremely difficult to master. It will be seen, therefore, that the Listening-In Service demanded of its operators continuous interest and constant vigilance, together with a sufficiently active imagination to enable them to piece together the broken or garbled fragments of messages which their instruments might pick up, and to deduce from these messages what the enemy was doing or what he intended to do. Listening-in was very far from being a one-sided game, however, for the Germans, who were thoroughly conversant with its possibilities and limitations, maintained a service which was nearly, if not fully, equal to our own. The real superiority of our service lay, not in its equipment, but in the boyish enthusiasm of its personnel, many of whom were university undergraduates when the war began. With them the work never assumed the aspect of a daily task which had to be performed whether they liked it or not: they regarded it rather as a game, interesting, fascinating, exciting. The quickness with which they grasped the technicalities of the service was amazing. I knew of one case where a soldier of a Listening-In Section, wholly without previous experience in the work, overhearing a telephone conversation in the enemy’s lines which indicated that the watches in that sector were being synchronized, deduced that a raid on the American trenches was being planned. He promptly acquainted the divisional intelligence officer with his conclusions, and when the Germans launched their attack, expecting to take the verdamte Yankees completely by surprise, they were greeted by a burst of rifle and machine-gun fire which almost annihilated them. After the moving warfare began it was, of course, extremely difficult to maintain these listening-stations, but when the advance halted, even for a night, listening-stations were always established if conditions permitted.

A far-fetched but, as it proved, entirely correct deduction was made by the operator of a listening-post whose curiosity was aroused by the sudden change in the nature of the conversation taking place over the enemy’s lines, familiarity interspersed with profanity abruptly giving way to studied politeness. From this he reasoned that a new division had moved in during the night. Prisoners captured the next day verified his deduction. Just before the St. Mihiel offensive one of our operators noted that the telephone conversations between the enemy units opposite his station had almost ceased, presumably because a troop movement was in progress which they did not dare to discuss for fear of being overheard, the truth being that the Germans were quietly withdrawing. Though he had practically no conversation to guide him, this by no means discouraged the American listener, who, by comparing the intensity of the T. P. S. (telegraphie par sol) signals he overheard, deduced with amazing accuracy the movements of the retiring troops. In comparison with such feats of deduction, Sherlock Holmes’s ability to deduce a stranger’s occupation from the condition of his finger-nails or the soles of his boots seems absurdly commonplace, doesn’t it?

A youth in search of excitement beyond that usually provided by battle could always find it by joining the Listening-In Service. In March, 1918, the American troops holding a certain sector were suddenly ordered to retire to a second line of resistance, but through an oversight the orders for withdrawal were not passed on to the Signal Corps men who were operating the listening-stations out in front. Serenely unconscious, therefore, of the fact that their comrades had fallen back and that German raiding-parties were prowling all about them in the darkness, they remained at their post throughout the night. It was not until the American infantry reoccupied their original position in the morning that the men in the listening-station learned that for eight hours they had been the only occupants of the sector.

While crawling over No Man’s Land to repair a break in a line connecting his station with a ground-plate, a Signal Corps man discovered a wire leading straight toward the enemy’s position. Being of an inquiring turn of mind, he followed it up on hands and knees until he actually penetrated the German trenches, where he made the interesting discovery that the enemy’s listening-station had tapped the same ground which we were using. Needless to say, he lost no time in crawling back and changing his ground-plates. This feat was paralleled by a soldier who followed an American raid into the German trenches, and, unobserved during the excitement, succeeded in attaching a wire to one of their ground-plates which was well within their lines, and, therefore, presumably in no danger of being tampered with. By this means he listened-in on the enemy’s conversations for several days before his wire was discovered and cut.

Though the work of the Radio-Intercept and Goniometric Direction-Finding stations lacked in some measure the danger connected with that of the ground listening-posts, it nevertheless provided many interesting incidents in the life of the Signal Corps man. The function of radio-intercept stations is, as their name implies, the interception of enemy radio messages. Goniometric stations are used, on the other hand, for locating enemy radio-stations, the work being carried on on much the same principles as flash-ranging, which I have described at some length in another chapter. By placing a goniometer—an instrument for measuring angles—at each end of a base line of known length, it is a comparatively simple matter to ascertain the angle of direction of an enemy radio-station, and, by prolonging the lines of these angles until they intersect, the location of the station can be approximately determined. That done, the information was sent to the artillery, which proceeded to sweep the vicinity in which the radio-station was known to be with a hurricane of shell. So highly was this system of radio detection developed that, after the salient at St. Mihiel had been cleared of Germans, every radio-station which our Goniometric Service had located previous to the attack was verified, the greatest error in location being approximately 500 yards. In many cases some of the German wireless equipment was still in the dugouts, and much interesting printed matter was picked up. This was the first corroboration of the effectiveness of our Radio Intelligence work.

Just as the naturalists can reconstruct from a few bones a prehistoric monster which they have never seen, so the goniometric experts are able to gain an amazingly accurate idea of the organization of an army by locating its radio-stations, for the lines of radio communication which spread fan-wise from army headquarters form a sort of skeleton, as it were, of the army’s organization, the location of the various stations and their distance from headquarters indicating quite accurately the position of the corps, divisions, brigades, regiments, and battalions. This fact was, of course, as well known to the Germans as to ourselves, and consequently extraordinary precautions were taken to prevent the stations from being located. Such a system of communications is known in military parlance as a “net,” that serving an army being called an “army net” and that of a corps a “corps net.” Just before the American offensive was launched at St. Mihiel a false corps net was set up considerably to the east of the point selected for the attack, this net being operated in as close imitation as possible of the real thing. Thousands of faked messages were sent in code, precisely as though the movements of an army corps depended upon them, and, to add to the verisimilitude of the proceeding, they were strongly seasoned with the profane and violent English with which American radio operators are accustomed to interlard their conversations. The German goniometric operators promptly located this network of radio-stations, and as the messages which were being transmitted appeared to be perfectly genuine, they naturally concluded that they had discovered the unsuspected presence of an American army corps, whereupon the German High Command took steps to move its reserves to the area which apparently was threatened. There is no means of knowing how effective this ingenious stratagem really proved, but the best answer would seem to be the surprisingly slight resistance which we encountered at St. Mihiel.

The operation of the mobile radio-stations which accompanied the smaller infantry units was always a most hazardous and trying business, requiring not only courage but a very high degree of resourcefulness and self-possession. In one case that I know of a Signal Corps unit received orders to have a trench radio-station installed at a certain exposed point by a certain time. They followed their instructions to the letter, but when their instruments were set up and they were ready for business, they discovered, to their extreme annoyance, that the infantry which was scheduled to occupy the position had failed to materialize and that they and their radio set were well in advance of our lines. From their position in a shell-hole they called up the regimental commander, reported that they were located according to instructions, and inquired what they were expected to do. Whereupon the infantry lost no time in moving up and occupying the position which, as the signalers mockingly asserted, they had been holding for them.

The exigencies of the Great War wrought many strange and startling transformations. Scientists who had devoted their entire lives to discovering methods for prolonging life turned their genius to finding new and effective ways of taking it; the tractor of the Western wheat-fields became the tank of the battle-fields in Flanders; the machinery and chemicals used for the manufacture of dyestuffs were converted to the manufacture of poisonous gases—and the dove became the army carrier-pigeon, bearing, instead of the olive-branch of peace, messages of battle. Though I find that many Americans seem to be under the impression that pigeons were unreliable and comparatively little used, they were, as a matter of fact, the most trustworthy of all the systems of message transmission employed by the fighting armies. When everything else failed, when the wires of the field telegraph and telephone had been destroyed by the German shell-storms, when the radio installations had been demolished, when the runners had been killed and the aviators driven back by the air-barrages, it was the pigeons which took the messages through. The official accounts of their exploits read like the wildest fiction. Over 500 birds were used by our troops in the St. Mihiel offensive alone. Through the messages brought by pigeons, American Headquarters learned of the whereabout of Major Whittlesey and his “Lost Battalion.” How trustworthy were these winged messengers is proved by the carefully kept records of the Allied Armies, which show that of the thousands of messages intrusted to pigeons during the four years of the war, 96 per cent were delivered.

The use of pigeons as messengers is as old as recorded history, the Chinese, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans all having used birds for this purpose. Word of the victory at Waterloo was brought to England by pigeons, and pigeons carried from New York to Washington the news that Napoleon had signed the treaty which added Louisiana to the Union. Among the oldest and most successful pigeon-trainers are the Belgians, many of the best flying strains used by the French, British, and American armies having been developed from Belgian stock. When the Hunnish hordes swept across Belgium, one of their first measures was to confiscate or kill all pigeons. For a Belgian to have in his possession a carrier-pigeon was for him to risk a court martial and death before a firing-party. Many of the pigeons taken from the Belgians were sent back to Germany for breeding purposes, producing birds which served against their former masters, but when the Americans established their watch on the Rhine, they ordered the immediate release of all pigeons in the area of occupation, thus giving thousands of feathered exiles a chance to fly back to their old homes in Flanders.

The Carrier-Pigeon Service of the American Army is a part of the Signal Corps, being composed of officers and men who are expert pigeon breeders and handlers, and who have the ability to impart their knowledge to others. The pigeon section, which was organized shortly after our entry into the war, consisted of two companies with a personnel of 24 officers and about 650 men. The birds used by the army are known to the fancier as “homers” and are really not carrier-pigeons at all, the latter being a large, ungainly show-bird that cannot fly a city block. But our allies persist in calling homers “carrier-pigeons,” and our military authorities have adopted the term. The homer has all the qualities required of a military messenger. He is a strong, well-built, racy-looking bird, possessed of indomitable courage. His most characteristic trait is, of course, his remarkable ability to find his home when released at great distances from it. This power, which has been developed by scientific breeding to an almost uncanny degree, is the asset which makes the bird of enormous value to the army. Though scientists have attempted to explain the homing instinct, they have arrived at different and frequently contradictory conclusions, it being enough to know that it is an instinct with which all birds are endowed to a greater or less degree, and which has been developed in the homer to a stage where it is limited only by the bird’s physical endurance. Nature has equipped the pigeon with numerous air-sacs adjoining the lungs, in which a reserve supply of warm air is carried and supplied to the lungs as needed during flight. Over the eye is a transparent lid, called a “blinder,” which protects the eye while in flight, and is at the same time transparent, thus providing a sort of natural goggle. Well-trained homers have frequently flown 1,000 and even 1,500 miles, while pigeon-fanciers think no more of a 500-mile flight than horsemen do of a mile trotted in 2:30. On clear days a homer pigeon will fly distances up to 300 miles at a speed close to a mile a minute, though longer distances are usually covered at a somewhat lower rate of speed, the birds instinctively taking advantage of the favoring air-currents and increasing or decreasing their altitude in order to obtain the benefit of them.

Long before the Great War it was discovered that pigeons would “home” to movable lofts as unerringly as to stationary ones, this being of great importance from the military point of view because it made it possible to move the cotes up to within a few miles of the firing-line. It also made it comparatively easy to supply the advanced posts with fresh pigeons. It was found that a week or ten days was usually sufficient to acquaint the birds with the new location of the loft and with the surrounding country, moves of twenty-five miles without the loss of any birds being not at all uncommon. Each of these mobile lofts was stocked with seventy-five young birds, six to eight weeks old, of the best pedigreed stock obtainable. Clasped about the leg of each bird was a seamless aluminum band bearing a serial number, the year of birth, and the letters “U. S. A.” These bands are put on soon after birth and cannot be removed except by destroying them. As the birds had never been outside a loft, it was a comparatively easy matter to settle them in their new homes. Their early training was devoted to the development of their flying strength and stamina and to the habit of quick “trapping,” by which is meant the entrance of the bird into the loft immediately upon reaching it, a pigeon that alights on the ground or roosts on the roof of the loft being considered most imperfectly trained. They soon learn to trap without hesitation, a flock of seventy-five birds entering a loft in from ten to twenty seconds after pitching on the roof. To overcome the habit of loafing, birds are fed in the loft after alighting with their favorite grain. After a month or two of this preliminary training the birds are “tossed,” to use the phraseology of the fancier, at increasing distances from the loft, so that by the time they are five or six months old they are flying from fifty to seventy-five miles with speed and certainty. They are then ready for service in the trenches. Not all, however, are assigned to the infantry. Every tank crew carries a complement of pigeons, men from the Pigeon Service are frequently attached to cavalry units, and birds have been used successfully from balloons and airplanes. The infantryman carries his pigeons in a light wicker hamper strapped to his back, each bird wearing a corselet made of crinoline stiffened with whalebone and with strings running to the sides of the basket, thus preventing it from being tossed about and injured.

As long as the ordinary means of communication are working satisfactorily, birds are not used. But when a barrage is laid down and the telephone-wires are destroyed, resort is had to the pigeons. When an advance-party has pushed far ahead of the main force it, too, relies on this method of liaison. In short, when every other method of liaison has failed or is unavailable, important messages are intrusted to the birds. The messages are written on fine tissue-paper, folded into a small wad, and inserted in the aluminum holder which is attached to the leg of each pigeon. The bird is then released, and in spite of the terrific din and confusion of battle, in spite of the enemy shotgun squads, composed of expert shots, whose duty it is to pick off carrier-pigeons, it wings its way through shell and gas barrages to its loft in the rear of the lines. I might mention in passing that though birds are frequently killed while in their baskets by exploding shells, and others die from long confinement without food or care in the trenches, those that survive become accustomed to the roar of cannon and never suffer from shell-shock. On reaching his loft the bird hurries into it through an opening which permits of entry but not of exit, the dropping back of the little door ringing a bell which announces the arrival of a message from the front, whereupon eager hands strip the cylinder from the leg of the bird, the message which it contains being relayed to headquarters by telephone or despatch-rider.

The pigeons were not always fortunate enough, however, to pass through the battle area unscathed, many birds having succeeded in reaching their lofts with their messages only to succumb to their wounds. During the offensive in the Argonne an American pigeon reached its loft with the leg to which the message was attached severed and dangling by the ligaments, the missile that severed the leg having also passed through the breast-bone. In spite of these injuries and the great loss of blood the heroic bird flew twenty-five miles with a message of vital importance. I am glad to say that the pigeon recovered and was recommended in due form for the D. S. C. An English bird was struck by a piece of shrapnel while homeward bound with a message. Both of its legs were broken and the aluminum message-holder was embedded in the flesh by the force of the bullet. But its spirit never faltered. It struggled on and on, blood dripping from it in an ever-increasing stream, to fall dead at the feet of the loft attendants. Another bird was released from a seaplane which had fallen and was being shelled by a German destroyer. It rose quickly and circled once to get its bearings. Shots resounded from the deck of the destroyer, the bird stopped short in its flight, and a flurry of falling feathers told their tale, but, after a short fall, it recovered and valiantly struggled on. Within thirty minutes after its release three British destroyers, white waves curling from their prows and clouds of smoke belching from their funnels, came racing toward the scene, whereupon the German turned and fled and the aviators were saved. With wings and body terribly lacerated the plucky bird had flown thirteen miles to a naval air-station and given the alarm. Here is another incident in which a feathered messenger played a hero’s rôle. A detachment of French infantry was ordered to hold a certain strategic position at all costs, thereby affording their main body time to retire to another position. The Germans, realizing that the stubborn little band of Frenchmen was balking them of their prey, launched attack after attack, until, borne down by sheer weight of numbers, the defenders were literally engulfed by the wave of men in gray. Just as all that remained of the detachment were making their last stand, a blood-stained pigeon fell exhausted in a French loft behind the lines. The message which it bore read:

“The Boche are upon us. We are lost, but we have done good work. Have the artillery open on our position.”

Little has been said about the work of pigeons in this country. Over a hundred lofts were established at the various camps and cantonments, the thousands of birds which they housed proving of no inconsiderable value in the training of the troops for fighting overseas. Everywhere that they were used the birds showed a dependability which won for them the enthusiastic admiration of all who were familiar with their work. Indomitable courage, a gameness which ends only with death, and a burning love of home are among the qualities most cherished by Americans, and nothing possesses them to a greater degree than the army carrier-pigeon.

Though the Belgians made extensive use of dogs for hauling machine-guns, and though the French used them to a certain extent for liaison work and the British for locating the wounded, they were not utilized by the American forces overseas. A considerable number of dogs, most of them police-dogs and Airedales, were trained at the various camps and cantonments in this country, however, and had the war continued they would undoubtedly have proved of real service in certain forms of work in France. The attitude of the American soldier toward the subject of dogs is best expressed by a story which I heard in France. An American officer, lost at night in No Man’s Land, sought refuge in a shell-hole. He found, however, that it already had an occupant, an American doughboy—from his accent evidently a product of the Bowery—who, it appeared, was lost like himself. In the periodic bursts of light afforded by the star-shells the officer noticed that the man had strapped to his back what appeared to be a large basket.

“What have you in there?” he inquired curiously.

“Boids, cap’n, boids,” the soldier answered in a hoarse whisper, adding disgustedly: “An’ that ain’t the woist of it, cap’n. I hear they’s goin’ to give us dawgs!”

Though Americans have always been the greatest photographers in the world, the Yankee abroad being readily distinguishable by his ever-ready kodak, it is a rather surprising fact that it needed the World War to convince the American military authorities of the vital importance to the army of the camera. Upon our entry into the war, however, the War Department, following the example of the European armies, established a photographic section, with a personnel of forty-odd officers and nearly 800 men, as a part of the Signal Corps. The duty of this section was to take pictures, both still and motion, of every phase of America’s participation in the war, both on the fighting front in Europe and in the training-camps at home; for the information of the intelligence officers of the A. E. F., for the guidance of the artillery, for purposes of instruction in the schools and cantonments, for propaganda use at home and in foreign countries, and for illustrating the official history of the great conflict.

The photographic section was divided into two branches, land and air, the latter being, perhaps, from a military standpoint, the more important of the two for the reason that airplanes were used primarily for reconnaissance work and were, when equipped with cameras, literally the eyes of the army. The airplane being the eye of the army, the camera may be said to have been the pupil of the eye. In order to provide the large and highly trained personnel required for this service, there was established at Rochester, New York, a School of Aerial Photography—the largest in the world—where candidates received, in addition to a thorough military training, a course of instruction in everything relating to modern photography, from the manufacture of plates and films through the selection and use of lenses, shutters, and light-filters, to the printing of the picture itself. In addition to becoming familiar with these details of commercial photography, they were instructed in all the special phases of military photography, such as map-plotting, mosaics, enlargements, and the study of topography from a negative made many thousands of feet in the air. As in that chapter dealing with the Air Service I have described in considerable detail the methods and instruments used in aerial photography, it is enough to say here that the aerial branch of our Photographic Service attained such a degree of efficiency that, in the closing months of the war, it became virtually impossible for the Germans to dig a dozen yards of new trench, to transfer a platoon, to change the position of a machine-gun, without being detected by the all-seeing eyes of our cameras.

The mother school for land photography was located at Columbia University, in New York, where the students received the same thorough training which was given to the aerial operators at Rochester, with instruction in motion-picture photography added. The students at this school were the pick of the newspaper photographers and motion-picture operators of America. Among them were men who had “snapped” presidents and potentates, celebrities and notorieties, prize-fighters, reformers, murderers, prelates, politicians and statesmen, leaders of society, Society and near-society; who had “filmed” presidential inaugurations, Newport weddings, railway disasters, yacht-races, South Sea cannibals, Mexican revolutions, and Heaven knows what besides. Their courage and resourcefulness were precisely the qualities which were required of army photographers, for there was nowhere that they would not go, nothing that they would not do, and the more danger there was in their work the more it appealed to them. When a new type of gun was being fired for the first time and the gun crew took refuge in the bomb-proofs as a precaution against accident, the army movie-men moved their machines up close in the hope that if the gun exploded they would get a picture of the explosion. One of the Signal Corps operators, Captain Edward N. Cooper, with his assistant, Sergeant Adrian Duff, while attached to the Twenty-Sixth Division, crawled out into No Man’s Land just before an attack was scheduled to take place, and, though exposed to both German and American fire, set up their machine in order that the people at home, seated comfortably in motion-picture theatres, might actually see the boys going “over the top.” On another occasion this same young officer became separated from the troops to which he was attached and found himself under the fire of a German machine-gun, but in spite of the hail of bullets he stuck to his work, made his pictures, and returned to the American lines herding in front of him a group of Germans whom he had captured single-handed at the point of an empty revolver. A camera-man whom the French Government detailed to accompany me along the Western Front in 1916 was seriously wounded by a German shell just as we were leaving Verdun. His assistant helped me to give first aid to his chief and then, though the road was being heavily bombarded, coolly set up his machine and turned the crank while the wounded man was being lifted into an ambulance. It is a striking commentary on the scepticism of American audiences that, when I showed that picture in the United States, fully half of the people who saw it insisted that it had been faked. Another officer of the photographic section who, before our entry into the war, as the representative of a Chicago newspaper had accompanied the German Armies during the invasion of Poland, was present at the capture of Warsaw. When the Kaiser reviewed the troops after his triumphal entry into the captured city, the American pushed his way through the cordon of soldiers and police agents which surrounded the imperial motor-car, set up his machine within six feet of the astonished Emperor, and proceeded to take a “close-up” of the All Highest, who was so amused by the effrontery of the performance that he insisted on shaking the photographer’s hand!

MOTION-PICTURE OPERATORS OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC SECTION OF THE SIGNAL CORPS GOING INTO ACTION ON A TANK

There was nowhere they would not go, nothing that they would not do, and the more danger there was in their work the more it appealed to them.

Photograph by Signal Corps, U. S. A.

AN OFFICER OF THE SIGNAL CORPS OPERATING A TELEPHONE AT THE FRONT.

This instrument was so compact that it could be carried as part of the equipment of a soldier and quickly put into operation.

Photograph by Signal Corps, U. S. A.

Motion-pictures were used in the training of troops far more generally than the public realized. A series of pictures taken at the Military Academy at West Point and exhibited at every camp and cantonment in the United States did more in a few hours to acquaint the troops with military etiquette and the evolutions of the squad, the platoon, and the company than any number of drills and lectures could have done. “Animated drawings,” as they are called—like those of Mutt and Jeff and the Katzenjammer Kids—were made under the direction of the Signal Corps for the purpose of familiarizing the men with the mechanism of the service rifle, the automatic pistol, and the various types of machine-guns. By running these pictures slowly, every stage of the operation of loading and firing was made clear, from the insertion of the cartridge into the clip or belt to the bullet leaving the muzzle. But the greatest value of the motion-picture, when all is said and done, was in keeping up the morale of the American people by combating the insidious and undeniably clever propaganda which was carried on in this country by the Germans. Enemy agents spread reports that the drafted troops were being ill-treated in the camps, that they lived in wretched quarters, were poorly fed, and suffered from lack of proper clothing. To answer these charges a score of movie-men were despatched to the various camps, the pictures which they took and which were exhibited throughout the country showing the clean and comfortable barracks, the men seated at their bountiful and appetizing meals in the mess-halls, the football and baseball games, the camp theatres, and the other features of cantonment life, thus providing a convincing refutation of the German insinuations. Parents who had heard the widely circulated tales of the unsanitary and immoral conditions to which their boys were exposed in France could go to their local motion-picture houses and see for themselves the clean dormitories, the Y. M. C. A. and Knights of Columbus huts, the social gatherings, the splendidly equipped hospitals, incidents of life in the back areas and in the trenches, and not infrequently the faces of their loved ones themselves, sun-bronzed and happy, wearing “the smile that won’t come off.” If the photographic section of the army had accomplished nothing else, its existence would have been justified a thousand times over by the service which it performed in fighting the propaganda of the Hun and in bringing cheer and comfort to the parents, wives, and sweethearts whom the boys had left behind them.

As a result of the researches and experiments which it carried on during the war, the Signal Corps has, in addition to its countless other achievements, produced several devices which are of such an astounding nature as to strain almost to the breaking-point the credulity of the layman. I am not permitting myself to indulge in the slightest exaggeration when I assert that these devices place in the hands of the United States weapons which would render this country wellnigh invulnerable in the event of our ever becoming involved in another war. But—and herein lies their greatest significance and interest—they are, beyond all question, the most important inventions, so far as their effect on the peaceful interests of the nation are concerned, which have been produced since Morse invented the telegraph, Bell perfected the telephone, and Marconi amazed us with the wireless. Imagine the value of a device which permits of a conversation being carried on between a person on the ground and an aviator in the clouds as easily as though they were seated opposite each other at a dinner-table! Such is the radiotelephone, which I have described in detail in the chapter on the Air Service but which was suggested and brought to a state of perfection by officers of the Signal Corps. Conceive, if you can, of another device which permits of nineteen separate and distinct telephone and telegraph messages being transmitted simultaneously over a single copper wire! Picture the advance in world-communication made possible by the discovery, made by General Squier, the Chief Signal Officer of the Army, that growing trees can be used as natural antennæ for both sending and receiving radio messages! And, as a climax to this amazing list of achievements, let your imagination attempt to grasp the military and commercial significance of a device for the sending over telegraph wires or cables of cipher messages which, though they can defy any system of deciphering known to science, appear in plain language at the other end! You may think, perhaps, that I am overenthusiastic; that I have used too many adjectives and exclamation-marks. But suppose that I tell you something about these inventions. Then, unless I am greatly mistaken, you will be guilty of adjectives and exclamations yourself.

Owing to the difficulty of constructing in France enough telegraph and telephone lines to meet the constantly increasing requirements of the American Expeditionary Forces, as well as to relieve the great congestion which prevailed on all of the existing lines, the scientists of the Signal Corps turned their attention early in the war to the possibility of sending several messages simultaneously over a single wire. Without entering into the details of the long series of experiments which were conducted by the Signal Corps, in conjunction with the American Telephone and Telegraph Company at Camp Alfred Vail, New Jersey, or attempting to describe in terms which would be intelligible to the non-technical reader the device which was finally perfected, it may be said that the result is accomplished through the application of radio, the wire serving as a guide for the radio currents and conducting them with a minimum of power and with a minimum of interference with other radio communications. This device has now been brought to such a state of perfection that eight telegraph messages and eleven telephone messages can be carried over a single wire at the same time, the Morse messages being transmitted by means of the multiplex telegraph apparatus—a system which was discovered as early as 1910 and is now in general use by the large telegraph companies—while the telephone conversations are guided by wireless waves, which serve as carriers for the voice currents. By placing on ordinary telegraph-wires wireless waves of very short length or of very great frequency, officers of the Signal Corps have successfully conversed over a line from Washington to Baltimore which was being used at the same time for the transmission of duplex telegraph messages. Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the performance was its extreme simplicity, the feat being accomplished merely by placing on the line, through proper connecting condensers, a pair of radiotelephone sets such as are used for communicating between ground-stations and airplanes. Whereas it was believed, until very recently, that it was impracticable to hold more than four wired-wireless conversations over one wire or one pair of wires, in addition to whatever ordinary telephone or telegraph conversation might be on that wire, the Signal Corps has now demonstrated that it is not only possible but entirely practicable to hold ten or more extra telephone conversations without their interfering with each other. Had this system been perfected while the war was in progress it would have meant that ten telephone and two or more telegraph conversations could have been carried on simultaneously with a point served only by a single wire. In other words, by the application of this system one wire will take the place of ten.

Another phase of science uncovered by the Signal Corps which figuratively makes the mind of the layman stand still and gasp is the discovery, due to the experiments of the Chief Signal Officer, General Squier, that trees can be used as instruments in the receipt and transmission of electrical messages, both telegraph and telephone, both by wire and wireless. Think of it, my friends! The commonplace tree possesses those very qualities that men have spent centuries of effort to embody in a frail spider’s web of wire!

“From the moment an acorn is planted in fertile soil,” to quote the words of General Squier himself, “it becomes a ‘detector’ and a ‘receiver’ of electromagnetic waves, and the marvellous properties of this receiver, through agencies at present entirely unknown to us, are such as to vitalize the acorn and to produce in time the giant oak. In the power of multiplying plant-cells it may, indeed, be called an incomparable ‘amplifier.’ From this angle of view we may consider that trees have been pieces of electrical apparatus from their beginning, and with their manifold chains of living cells are absorbers, conductors, and radiators of the long electromagnetic waves as used in the radio art. For our present purpose we may consider, therefore, a growing tree as a highly organized piece of living earth, to be used in the same manner as we now use the earth as a universal conductor for telephony and telegraphy and other electrical purposes.”

Not only have telephone conversations, in which the voice is transmitted just as clearly as by the ordinary metallic circuit telephone, been carried on from tree to tree, up to a distance of three miles, in the outskirts of Washington, but while the war was still in progress the signal officers, using tree-tops as antennæ, read messages from ships at sea, from aviators in the sky, and from the great radio-stations in South America and Europe. As a result of this discovery, the lofty and costly towers which are now used for the sending and receipt of radio messages will no longer be a necessity. All that will be necessary is to drive a spike in a tree, attach a wire to the spike, and run the wire to a radio apparatus, whereupon messages can be received and sent, the distance covered depending upon the power of the instrument. The tree telegraph has been dubbed by General Squier a “floragraph” and the tree telephone a “floraphone,” while the messages transmitted over this arboreal system are to be known as “floragrams.” Though this discovery will in all likelihood result in an amazing expansion of the world’s system of communication, and though it will give radio-towers, thousands of them, in fact, to every village and to every farm, it does not necessarily mean that every man who possesses a vine and fig-tree will be able to sit on his front porch and gossip with his neighbors.

During the war the offices of the Chief Signal Officer were literally besieged by persons who claimed to have invented various systems of message transmission which could not be tapped, or which, if they were tapped, could not be understood. It was perfectly well known to us, of course, that the German Listening-In Service, particularly in the front-line trenches, was well organized and extremely efficient, and that telephone and buzzer conversations held over our wires were frequently intercepted. It was known, moreover, that Germany had spies, both in France and the United States, whose sole duty it was to tap the governmental telephone and telegraph systems for the purpose of obtaining military information. Scores of devices designed to secure the inviolability of the vitally important messages which were constantly passing over the wires were submitted to the Signal Corps. Anxious as they were to obtain a system of message transmission which could jeer at the efforts of the enemy’s spies, the experts of the Signal Corps steadily maintained that such a thing did not exist, for, as they said with truth, if an instrument could be devised which could transmit and decode a message, there was no reason why the Germans could not in time manufacture one like it, put it on the line, and thus obtain the information desired.

One of the inventors who approached the Signal Corps asserted that, though he did not claim to have a device which would render a message indecipherable, he had a system which made it impossible for an enemy agent to tap the wire over which messages were being transmitted without the sender and receiver being instantly notified that some one was eavesdropping upon them, whereupon their conversation would, of course, cease. “Prove it to us,” said the Signal Corps, and provided the inventor with an opportunity to demonstrate his system over a miniature line. Without the slightest difficulty the military experts tapped the line and, with the aid of a stenographer, recorded every message which was sent over it, the quantity of energy which they withdrew for the purpose being so minute that the delicate detectors failed to record the fact that the line had been tampered with.