The End of the Trail

E. Alexander Powell

THE END OF THE TRAIL

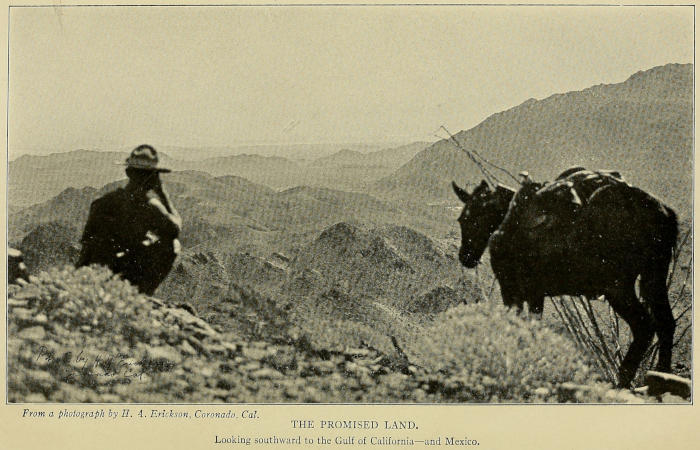

From a photograph by H. A. Erickson, Coronado, Cal.

THE PROMISED LAND.

Looking southward to the Gulf of California—and Mexico.

BOOKS BY E. ALEXANDER POWELL

Published by CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

| THE LAST FRONTIER: The White Man’s War for

Civilization in Africa. Illustrated. 8vo |

net $1.50 |

| GENTLEMEN ROVERS. Illustrated. 8vo | net $1.50 |

| THE END OF THE TRAIL. Illustrated. 8vo | net $3.00 |

THE

END OF THE TRAIL

THE FAR WEST FROM

NEW MEXICO TO BRITISH COLUMBIA

BY

E. ALEXANDER POWELL, F.R.G.S.

AUTHOR OF “THE LAST FRONTIER,” “GENTLEMEN ROVERS,” ETC., ETC.

WITH FORTY-EIGHT FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

AND A MAP

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1914

Copyright, 1914, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published November, 1914

TO

MY FRIEND AND FELLOW-ADVENTURER

ALBERT C. KUHN

OF

RANCHO YERBA BUENA

IN “THE VALLEY OF HEART’S DELIGHT”

FOREWORD

In the dim dawn of history the Aryans, forsaking the birthplace of the race upon the Caspian shore, poured through the passes of the Caucasus and peopled Europe. By caravel and merchantman adventuring Europeans crossed the western ocean and established a fringe of settlements along this continent’s eastern rim. The American pioneers, taking up the historic march, slowly but inexorably pressed westward, from the Hudson to the Ohio, from the Ohio to the Mississippi, from the Mississippi across the plains, across the Rockies, until athwart the line of their advance they found another ocean. They could go no farther, for beyond that ocean lay the overpopulated countries of the yellow race. The white man had completed his age-long migration toward the beckoning West; his march was finished; in the golden lands which look upon the Pacific he had come to the End of the Trail.

In the great march which substituted the wheat-field for the desert, the orchard for the forest, the work was done by the hardiest breed of adventurers that ever foreran the columns of civilisation—the Pioneers. And the pioneer has always lived on the frontier. Most people believe that there is no longer any quarter of this continent that can properly be called the frontier and that the pioneer is as extinct as the buffalo. To prove that they are wrong I have written this book. Though the gambler and the gun-fighter have vanished before the storm of public disapproval; though the bison no longer roams the ranges; though the express rider has given way to the express-train; in the hinterland of that vast region which sweeps westward and northward from the Pecos to the Skeena, and which includes New Mexico, Arizona, California, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, frontier conditions still endure and the frontiersman is still to be found. In the unexplored and unexploited portions of this, “the Last West,” white-topped prairie schooners—full sisters of those which crossed the plains in ’49—creak into the wilderness in the wake of the home seeker; the settler chops his little farmstead from the virgin forest and rears his cabin of logs from the trees which grew upon the site; mile-long pack-trains wend their way into the northern wild; six-horse Concord coaches tear along the roads amid rolling clouds of dust, their scarlet bodies swaying drunkenly upon their leathern springs; out in the back country, where the roads run out and the trails begin, the cow-puncher still rides the ranges in his picturesque panoply of high-crowned Stetson and Angora chaps and vivid shirt. But this is the last call. It is the last chance to see a nation in the primeval stage of its existence. In a few more years, a very few, there will be no place on this continent, or on any continent, that can truthfully be called the frontier, and with it will disappear, never to return, those stern and hardy figures—the pioneer, the prospector, the packer, the puncher—who won for us the West.

The real West—and by the term I do not mean that sun-kissed, flower-carpeted coast zone, with its orange groves and apple orchards, its palatial mansions and luxurious hotels, its fashionable resorts and teeming, all-of-a-sudden cities, which stretches from San Diego to Vancouver and which to the Eastern visitor represents “the West”—cannot be seen from the terraces of tourist hostelries or the observation platforms of transcontinental trains. Because I wished to visit those portions of the West which cannot be viewed from a car-window and because I wished to acquaint myself with the characteristics and problems and ideals of the people who dwell in them, I travelled from Mexico to the borders of Alaska by motor-car—the only time, I believe, that a car has made that journey on its own wheels and under its own power. Because that journey was so crowded with incident and obstacle and adventure, and because the incidents and obstacles and adventures thus encountered so graphically illustrate the conditions which prevail in “the Last West,” is my excuse for having to a certain extent made a personal narrative of the following chapters.

Without entering into a tedious recital of distances and road conditions, I have outlined certain routes which the motorist who contemplates turning the bonnet of his car westward might follow with profit and pleasure. With no desire to usurp the guide-book’s place, I have deemed it as important to describe that enchanted littoral which has become the nation’s winter playground as to depict that back country which the tourist seldom sees. Though I hold no brief for boards of trade and kindred organisations, I have incorporated the more significant facts and figures as to land values, soils, crops, climates, and resources which every prospective home-seeker wishes to know. But, more than anything else, I have tried to convey something of the spell of that big, open, unfenced, keep-on-the-grass, do-as-you-please, glad-to-see-you land and of the spirit of energy, industry, and determination which animates the kindly, hospitable, big-hearted, broad-minded, open-handed men who dwell there. They are the modern Argonauts, the present-day Pioneers. To them, across the miles, I lift my glass.

E. Alexander Powell.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Conquerors of Sun and Sand | 1 |

| II. | The Skylanders | 33 |

| III. | Chopping a Path to To-Morrow | 61 |

| IV. | The Land of Dreams-Come-True | 95 |

| V. | Where Gold Grows on Trees | 123 |

| VI. | The Coast of Fairyland | 155 |

| VII. | The Valley of Heart’s Delight | 187 |

| VIII. | The Modern Argonauts | 211 |

| IX. | The Inland Empire | 237 |

| X. | “Where Rolls the Oregon” | 271 |

| XI. | A Frontier Arcady | 305 |

| XII. | Breaking the Wilderness | 329 |

| XIII. | Clinching the Rivets of Empire | 351 |

| XIV. | Back of Beyond | 387 |

| XV. | The Map that is Half Unrolled | 419 |

| Index | 455 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| The Promised Land | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

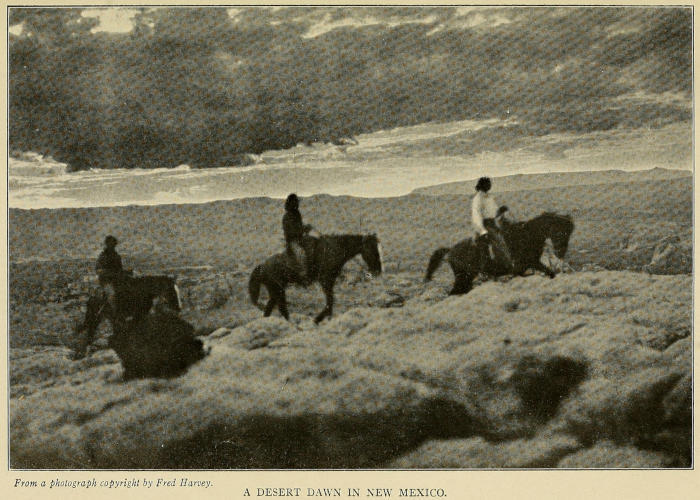

| A Desert Dawn in New Mexico | 4 |

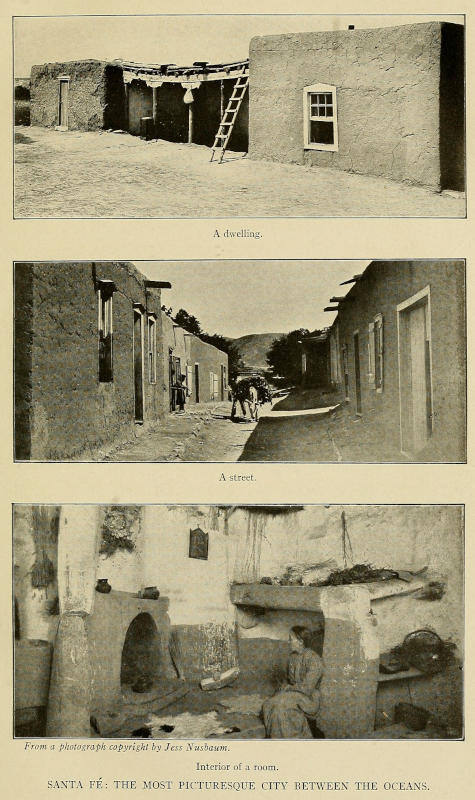

| Santa Fé: the Most Picturesque City between the Oceans | 18 |

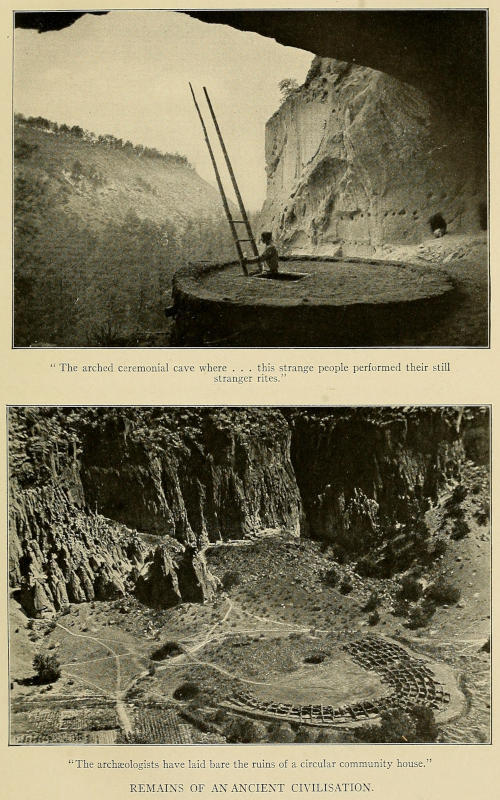

| Remains of an Ancient Civilisation | 24 |

| The Land of the Turquoise Sky | 38 |

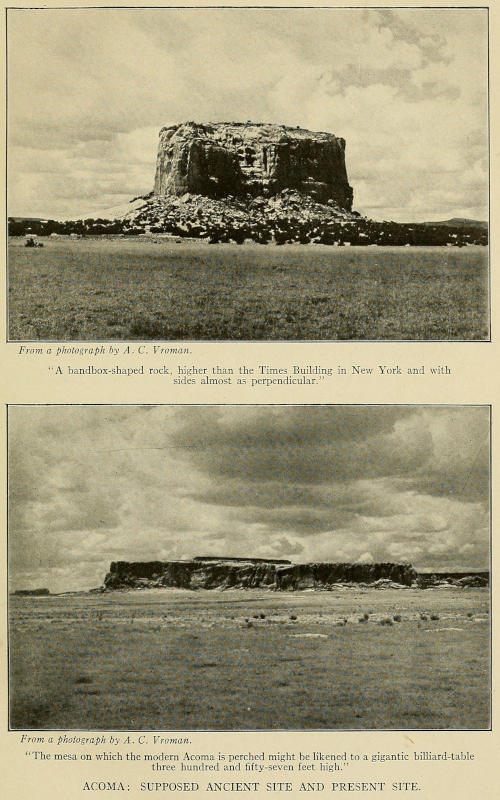

| Acoma: Supposed Ancient Site and Present Site | 40 |

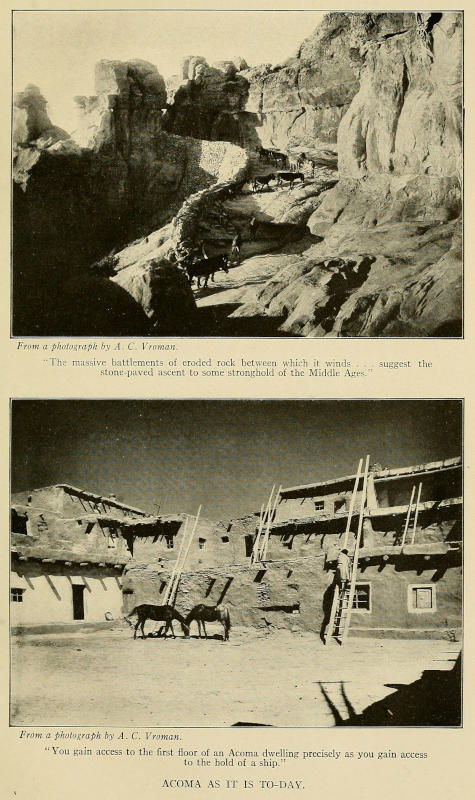

| Acoma as It is To-Day | 44 |

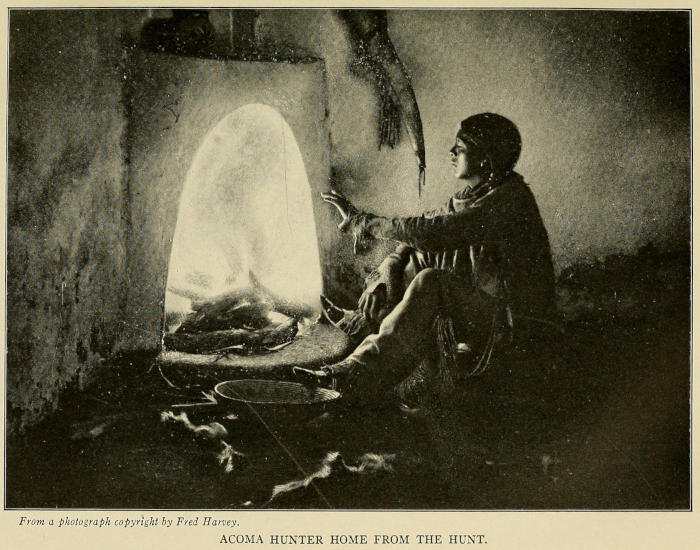

| Acoma Hunter Home from the Hunt | 48 |

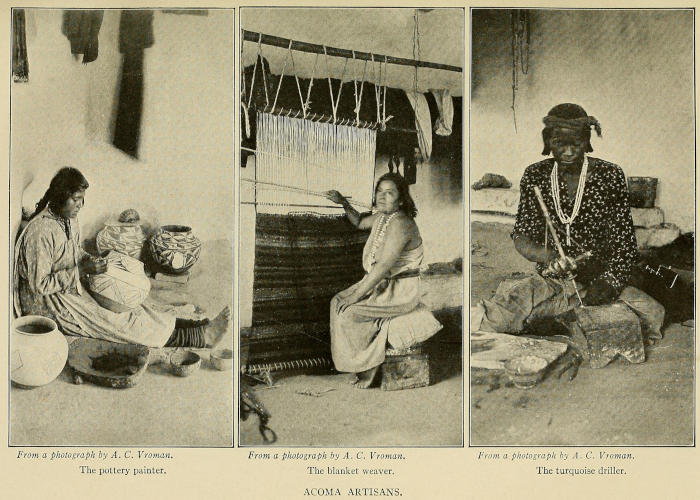

| Acoma Artisans | 50 |

| “Dance Mad!” | 52 |

| Young Acomans | 54 |

| The Education of a Young Hopi | 56 |

| The Pyramid-Pueblo of Taos | 58 |

| The Passing of the Puncher | 64 |

| Where the Roads Run Out and the Trails Begin | 72 |

| The Trail of a Thousand Thrills | 88 |

| Throwing the Diamond Hitch | 90 |

| Scenes in the Motor Journey Through Arizona | 98 |

| Not in Catalonia but in California | 120 |

| A Modern Version of the Sermon on the Mount | 130 |

| Santa Barbara, a City of Contrasts | 168 |

| The Mission of Santa Barbara | 170 |

| Lake Tahoe from the Slopes of the High Sierras | 232 |

| The Yosemite—and a Lady Who Didn’t Know Fear | 250 |

| Yosemite Youngsters, White and Red | 252 |

| The Greatest Oil Fields in the World | 260 |

| Over the Tehachapis | 262 |

| The Overland Mail | 274 |

| In the Oregon Hinterland | 284 |

| “Where Rolls the Oregon” | 300 |

| Where Rods Bend Double and Reels Go Whir-r-r-r | 324 |

| What the Road-Builders Have Done in Washington | 332 |

| The Unexplored Olympics | 344 |

| Where the Salmon Come from | 348 |

| Outposts of Civilisation | 354 |

| Breaking the Wilderness | 356 |

| Pack-Horses and a Pack-Dog | 358 |

| In the Great, Still Land | 362 |

| Sport on Vancouver Island | 376 |

| Life at the Back of Beyond | 380 |

| Transport on America’s Last Frontier | 382 |

| Transport on America’s Last Frontier | 384 |

| Scenes on the Cariboo Trail | 400 |

| Some Ladies from the Upper Skeena | 422 |

| Where No Motor-Car Had Ever Gone: Some Incidents of Mr. Powell’s Journey Through the British Columbian Wilderness | 428 |

| Some Siwash Cemeteries | 448 |

| Heraldry in the Hinterland | 450 |

| A Land of Sublimity and Magnificence and Grandeur, of Gloom and Loneliness and Dread | 452 |

| Map of the Far West, from New Mexico to British Columbia, Showing the Route Followed by the Author | at end of volume |

THE END OF THE TRAIL

I

CONQUERORS OF SUN AND SAND

I

CONQUERORS OF SUN AND SAND

“Isn’t this invigorating?” said a passenger on the Sunset Limited to a lounger on a station platform as he inhaled delightedly the crisp, clear air of New Mexico.

“No, sir,” replied the man, who happened to be a native filled with civic pride; “this is Deming.”

The story may be true, of course; but if it isn’t it ought to be, for it is wholly typical of the attitude of the citizens of the youngest-but-one of our national family. Indeed, I had not spent twenty-four hours within the borders of the State before I had discovered that the most characteristic and likeable qualities of its inhabitants are their pride and faith in the land wherein they dwell. And this despite the fact that their neighbours across the line in Arizona refer to New Mexico slightingly—though not without some truth—as a State “where they dig for water and plough for wood.”

Perhaps no region in the world, certainly none in the United States, has changed so remarkably in the space of a single decade. Ten years ago the only things suggested by a mention of New Mexico were cowboys, Hopi snake-dances, Navajo blankets, and Harvey eating-houses. Five years ago Deming was as typical a cow-town as you could find west of the Pecos. Gin-palaces and gambling-hells were running twenty-four hours a day; cattlemen in Angora chaps and high-crowned sombreros lounged under the shade of the wooden awnings and used the sidewalks of yellow pine for cuspidors; wiry, unkempt cow-ponies stood in rows along the hitching rails which lined a street ankle-deep in dust. Those were the careless days of “chaps and taps and latigo-straps,” when writers of the Wild West school of fiction could find characters, satisfying as though made to their order, in every barroom, and groups of spurred and booted figures awaited the moving-picture man (who had not then come into his own) on every corner.

All southern New Mexico was held by experts—at least they called themselves experts—to be a waterless and next-to-good-for-nothing waste. Government engineers had traversed the region and, without considering it worth the time or trouble to sink test wells, had written it down in their reports as being a worthless desert; and the gentlemen who make the school geographies and the atlases followed suit by painting it a speckled yellow, like the Sahara and the Kalahari. Real-estate operators, racing westward to earn a few speculative millions in California, glanced from the windows of their Pullmans at the tedious expanse of sun-swept sand and, with a regretful sigh that Providence had been so careless as to forget the water, settled back to their magazines and their cigars. So the cattlemen who had turned their longhorns in among the straggling scrub, to get such a living as they could from the sparse desert grasses, were left in undisturbed possession, and if their uniform success in finding water wherever they sank their infrequent wells suggested any agricultural possibilities they were careful to keep the thought to themselves.

From a photograph copyright by Fred Harvey.

A DESERT DAWN IN NEW MEXICO.

One day, however, one of the men in the Pullman, instead of leaning back regretfully, descended from the train, hired a horse, and rode out into the mesquite-dotted waste. He told the liveryman that he was a prospector, and, in a manner of speaking, he was. Being, incidentally, the manager of one of the largest and most profitable ranches in California, he was as familiar with the vagaries of the desert as a cowboy is with the caprices of his pony; and, moreover, he understood the science of irrigation from I to N. After a few days of quiet investigation he dropped into the commissioner’s office in Deming one morning and filed a claim for several hundred acres of land. Most of those who heard about it said that he was merely a fool of a tenderfoot who was throwing away his time and money and who ought to have a guardian appointed to take care of him, but some of the wise old cattlemen looked worried. Within a fortnight he had erected his machinery and was drilling for water. And wherever his wells went down, there water came up: fine, clear, sparkling water—gallons and gallons of it. It soused the thirsty desert and turned its good-for-nothing sand into good-for-anything loam. The seeds which the far-seeing Californian planted, sprouted, and the sprouts became blades, and the blades shot into stalks of alfalfa and corn and cane—and the future of all southern New Mexico was assured.

The news of the discovery of water in the Mimbres valley and of the miracles that had been performed through its agency spread over the country as though by wireless, and sun-tanned, horny-handed men from half the States in the Union began to pile into Deming by every train, eager to take up the land while it was still to be had under the hospitable terms of the Homestead and Desert Land acts. It was in 1910 that the Californian, John Hund, sunk his first well; when I was in the office of the United States commissioner in Deming four years later I found that the nearest unoccupied land was sixteen miles from the city limits.

Should you ever have occasion to fly over New Mexico in an aeroplane you will have no difficulty whatever in recognising the Mimbres valley; viewed from the sky it looks exactly like a bright-green rug spread across one end of a vast hardwood floor. Most of the valley holdings were, I noticed, of but ten or twenty acres, comparatively few of them being more than fifty, for the New Mexican homesteader has found that his bank-account increases faster if he cultivates ten acres thoroughly rather than a hundred superficially. This lesson they have had hammered into them not alone from experience but from observing the operations of a couple of almond-eyed brethren named Wah, hailing originally, I believe, from Canton, who own a twenty-three-acre truck-farm near Deming. Those vineyards on the slopes of Capri and those farmsteads clinging to the rocky hillsides of Calabria, where soil of any kind is so precious that every inch is tended with pathetic care, seem but crude and amateurish efforts in agriculture when compared with the efforts to which these Chinese brothers have carried their intensive farming. Though watered only by a small and primitive well, their farm graphically illustrates what can be accomplished by paying attention to those little things which the American farmer is accustomed contemptuously to disregard, as well as being an object-lesson in the remarkable variety of fruits and vegetables which the valley is capable of producing. These Chinamen make every one of their acres produce three crops of vegetables a year. Not a foot of soil is wasted. They even begrudge the narrow strips which are used for paths. Fruit-trees and grape-vines border the banks of the irrigation channels, and peas, beans, and tomatoes are grown between melon rows. A drove of corpulent porkers attend voraciously to the garden refuse and even the reservoir has had its usefulness doubled by being stocked with fish. Were the New Mexicans notoriously not lotus-eaters, the Brothers Wah would doubtless find still another use for their reservoir by raising in it the Egyptian water-lily. It is paying attention to such relatively insignificant details as these which makes J. Chinaman, Esquire, the best gardener in the world. It pays, too, for they told me in Deming that the Wahs, from their twenty-three-acre holding, are increasing their bank-account at the rate of eight thousand dollars a year. After noting the cordiality with which they were greeted by the president of the local bank, I did not doubt it. I should like to have a bank president greet me the way he did them.

I have seen many remarkable farming countries—in Rhodesia, for example, and the hinterland of Morocco, and the Crimea, and the prairie provinces of Canada, not to mention the Santa Clara and the Imperial valleys of California—but I can recall none where soil and climate seemed to have combined so effectively to befriend the farmer as in the valley of the Mimbres. Imagine what a comfort it must be to do your farming in a region where you will never have to worry about how long it will be before it rains, nor to tramp about in the mud afterward. As the annual rainfall in this portion of New Mexico does not exceed eight inches, there is a generous margin left for sunshine. Instead of praying for rain, and then cursing his luck because it doesn’t come, or because it comes too heavily, the New Mexican farmer strolls over to his artesian well and throws over an electric switch which sets the pump agoing. When his fields are sufficiently irrigated he throws the switch back again. From the view-point of health it would be hard to improve upon the climate of the Mimbres valley, or, for that matter, of any other portion of New Mexico, its elevation of four thousand three hundred feet, taken with the fact that it is in the same latitude as Algeria and Japan and southernmost California, giving it summers which are hot without being humid or oppressive and winters which are never uncomfortably cold.

Like their neighbours in other parts of the Southwest, the farmers of southern New Mexico have gone daft over alfalfa. To me—I might as well admit it frankly—one patch of alfalfa looks exactly like another, and they all look extremely uninteresting, but I suppose that if they were netting me from fifty to seventy-five dollars an acre a year, as they are their owners, I would take a more lively interest in them. I never arrived at a town in New Mexico, dirty, hungry, and tired, but that there was a group of eager boosters with a dust-covered automobile awaiting me at the station.

“Jump right in,” they would say. “We have an alfalfa field over here that we want to show you. It’s only about thirty miles across the desert and we’ll get you back before the hotel dining-room is closed.”

They’re as enthusiastic about a patch of alfalfa in New Mexico as the Esquimaux of Labrador are about a stranded whale.

If you have an idea that you would like to be a hardy frontiersman and wear a broad-brimmed hat and become the owner of a ranch somewhere in that region which lies between the Gila and the Pecos, it were well to disabuse yourself of several erroneous impressions which seem to prevail about life in the Southwest. In the first place, you can dress just as much like the ranchmen whom you have seen depicted in the magazines as you wish—fleecy chaparejos and a horsehair hat band and a pair of spurs that jingle like an approaching four-in-hand when the wearer walks and all the rest of the paraphernalia—for they are a tolerant folk, are the New Mexicans, and have become accustomed to all sorts of queer doings by newcomers. In many respects they are the politest people that I know. When I was in New Mexico I carried a cane, and no one even smiled. But the newcomer must not imagine that he can gallop madly across the ranges, at least in the vicinity of the towns, for he is more likely than not to be hauled up before a justice of the peace and fined for trespassing on some one’s alfalfa field or cabbage patch. (Cabbages, though painfully prosaic, are about the most profitable crop you can grow in New Mexico; they pay as high as three hundred and fifty dollars an acre.) And the intending rancher must make up his mind that he must begin at the beginning. New Mexico is no place for the agriculturist de luxe who expects to sit on the piazza of his ranch-house and watch the hired men do the work. No, sirree! It is a roll-up-your-sleeves-spit-on-your-hands-and-pitch-in land where every one works and is proud of it. And there is always enough to do, goodness knows! This is virgin soil, remember, and first of all it has to be cleared of the piñon and mesquite and chaparral which cover it. This clearing and grubbing costs on an average, so I was told, about five dollars an acre, but you get a supply of fire-wood in return—and there’s nothing that makes a cheerier blaze on a winter’s night than a hearth heaped with the roots of mesquite. In other countries you chop down your fuel with an axe; in New Mexico you dig it up with a hoe. Then there is the matter of well digging, which, including the cost of boring, machinery, and housing, works out at from fifteen to twenty-five dollars an acre. Since the construction of several large power-plants, the cost of pumping has been greatly reduced by the use of electricity. It is quite possible, of course, for the five or ten acre man to secure tracts close to town with all the preliminary work done for him, water being provided from a central pumping plant and his pro-rata share of the capitalised cost added to the price of his land, which may be purchased, like a piano or an encyclopedia, on the instalment plan. That will be about all, I think, for facts and figures.

One of the most interesting things about the settlers with whom I talked in southern New Mexico is that, so far as any previous knowledge of agriculture was concerned, most of them were the veriest amateurs. One man whom I met had taught school in Iowa for a quarter of a century, but along in middle life he decided that there was more money to be made in teaching corn and cabbages how to shoot than there was in teaching the same thing to the young idea. Another was a Methodist clergyman from Kentucky who told me that he had never had a real conception of the hell-fire he preached about until he started in one scorching July morning to sink an artesian well in the desert. Still a third successful settler had been a physician in Oklahoma, while there are any number of “long-horned Texicans,” as the Texan cattlemen are called, who have moved over into New Mexico and become farmers. Scattered through the country are a few Englishmen; not of the club-lounging, bar-loafing, remittance-man type so common in Canada and Australia, but energetic, hard-working youngsters who are earnestly engaged in building homes for themselves in a new country and under an adopted flag. Not all of the Englishmen who have come out to New Mexico have proven so steady or successful, however, for a few years ago an English syndicate purchased a Spanish land grant of some two million acres in the vicinity of Raton and sent out a complete equipment of British managers, superintendents, foremen, butlers, valets, men servants, lodge keepers, gardeners, coachmen, and other functionaries, not to mention coaches, tandem carts, a pack of foxhounds, and other paraphernalia of the sporting life. A man who witnessed their detrainment at Raton told me that it was more fun than watching the unloading of the Greatest Show on Earth. It was a great life those Englishmen led while it lasted—tea at four every afternoon, evening clothes for dinner, and then a few rubbers of bridge—but it ended in the property being taken over at forced sale by a group of hard-headed Hollanders, who harnessed the four-in-hands to ploughs, used the tandem carts for hauling wood, set the hounds to churning butter, and are making the big place pay dividends regularly.

Some two hundred miles north of Deming as the mail-train goes is Albuquerque, the metropolis of the State—if the term metropolis can properly be applied to a place with not much over twelve thousand inhabitants—set squarely in the centre of the one hundred and twenty-two thousand square mile parallelogram which is New Mexico. Albuquerque is a railway centre of considerable importance, for from there one can get through cars north to Denver and Pike’s Peak, south to the borders of Mexico and its revolutions, and west to the Golden Gate. One of the things that struck me most forcibly about Albuquerque—and the observation is equally applicable to all the rest of New Mexico—is that instead of having weather they enjoy climate. It is pretty hard to beat a land where the moths have a chance to eat holes in your overcoat but never in your bed blankets. Climate is, in fact, Albuquerque’s most valuable asset, and she trades on it for all she is worth—and it is worth to her several million dollars per annum. It is one of the few cities that I know of where they want and welcome invalids and say so frankly. They could not do otherwise with any consistency, however, for half the leading citizens of the town arrived there on their backs, clinging desperately to life, and were lifted out of the car window on a stretcher. These one-time invalids are to-day as husky, energetic, up-and-doing men as you will find anywhere. Heretofore Albuquerque has been much too busy catering to the wants of the thousands of tourists and invalids who step onto its station platform each year to pay much attention to agricultural development; but bordering on the town are several thousand acres of as fine, healthy desert as you will find anywhere outside of the Sahara. They are enclosed, as though by a great garden wall, by the Manzano ranges, and the gentleman who whirled me across the billiard-table surface of the desert in his motor-car told me that the government now has an irrigation project under consideration which, by damming the waters of the Rio Grande, will reclaim upward of four hundred thousand acres of this arid land. And the great government irrigation projects now in operation elsewhere in the Southwest have shown that water can produce as many things from a desert as the late Monsieur Hermann could from a gentleman’s hat. So one of these days, I expect, the country around Albuquerque, from the city limits to the distant foot-hills, will be as green with alfalfa as Ireland is with shamrock.

They have a commercial club in Albuquerque that is a club. At first I thought I had wandered into a hotel by mistake, for, with its spacious lobby, its busy billiard-tables, its handsome rugs and furniture, and the mahogany desk with the solicitous clerk behind it, it is about as distantly related to the usual commercial club as one could well imagine. It gives those men in the community who are doing things, and the others who want to be doing things or ought to be doing things, a place where they can meet and discuss, over tall, thin glasses with ice tinkling in them, the perennial problems of taxes, pavements, irrigation, crops, fishing, house building, automobiles, and the climate. I would suggest to the club’s board of governors, however, that it take steps to remove the undertaker’s establishment which flanks the entrance. When one drops into a place to get some facts regarding the desirability of settling there, it is not exactly reassuring to be greeted by a pile of coffins.

Whoever was responsible for the architecture of the University of New Mexico buildings, which stand in the outskirts of Albuquerque, deserves a metaphorical slap of commendation. New Mexico is a young State and not yet overly rich in this world’s goods, so that if, with their limited resources, they had attempted to erect collegiate buildings along the usual hackneyed lines, with Doric porticoes and gilded cupolas and all that sort of thing, the result would probably have looked more like a third-rate normal school than like a State university. But they did nothing of the sort. Instead, they erected buildings adapted from the ancient communal cliff dwellings, constructing them of the native adobe, which is durable, inexpensive, warm in winter and in summer cool. All the decorations, inside and out, are Indian symbols and pictures painted in dull colors upon the adobe walls. Thus, at a moderate cost, they have a group of buildings which typify the history of New Mexico and are in harmony with its strongly characteristic landscape; which are admirably suited to the climate; and which are unique among collegiate institutions in that they are modelled after those great houses in which the Hopi lived and worked before the dawn of history on the American continent.

Santa Fé, the capital of the State, is, to my way of thinking, the quaintest and most fascinating city between the oceans. Very old, very sleepy, very picturesque, it presents more neglected opportunities than any place I know. I should like to have a chance to stage-manage Santa Fé, for the scenery, which ranks among the best efforts of the Great Scene Painter, is all set and the costumed actors are waiting in the wings for their cues. Give it the advertising it deserves and the curtain could be rung up to a capacity house. Where else within our borders is there a three-hundred-year-old palace whose red-tiled roof has sheltered nearly five-score governors—Spanish, Pueblo, Mexican, and American? (In a back room of the palace, as you doubtless know, General Lew Wallace, while governor of New Mexico, wrote “Ben Hur.”) Where else are Indians in scarlet blankets and beaded moccasins, their braided hair hanging in front of their shoulders in long plaits, as common sights in the streets as are traffic policemen on Broadway? Where else can you see groups of cow-punchers on sweating, dancing ponies and sullen-faced Mexicans in high-crowned hats and gaudy sashes, and dusty prospectors with their patient pack-mules plodding along behind them, and diminutive burros trotting to market under burdens so enormous that nothing can be seen of the burro but his ears and tail?

Though at present it is only a sleepy and forgotten backwater, with the main arteries of commerce running along their steel channels a score of miles away, Santa Fé could be made, at a small expenditure of anything save energy and taste, one of the great tourist Meccas of America. To begin with, it is the only place still left in the United States where Buffalo Bill’s Wild West could merge into the landscape without causing a stampede. Those who know how much pains and money were spent by the municipality of Brussels in restoring a single square of that city to its original mediæval picturesqueness, whole blocks of brick and stone having to be torn down to produce the desired effect, will appreciate the possibilities of Santa Fé, where the necessary restorations have only to be made in inexpensive adobe. Desultory efforts are being made, it is true, to induce the residents to promote this scheme for a harmonious ensemble by restricting their architecture to those quaint and simple designs so characteristic of the country, the Board of Trade providing an object-lesson in the possibilities of the humble adobe by erecting a charming little two-room cottage, with an open fireplace, a veranda, and a pergola, at a total expense of one hundred dollars, but every now and then the sought-for architectural harmony is given a rude jolt by some one who could not resist the attractions of Queen Anne gables or Clydesdale piazza columns or Colonial red-brick-and-green-blinds.

Set at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Range, a mile above the level of the sea, with one of the kindliest all-the-year-round climates in the world, and with an atmosphere which is far more Oriental than American, Santa Fé has the making of just such another “show town” as Biskra, in southern Algeria, where Hichens laid the scene of “The Garden of Allah.” If its citizens would wake up to its possibilities sufficiently to advertise it as scores of Californian towns with not half of its attractions are advertised; if they would restore the more historically important of the crumbling adobe buildings to their original condition and erect their new buildings in the same characteristic and inexpensive style; if they would keep the streets alive with the colourful figures of blanketed Indians and Mexican venders of silver filigree; and if the local hotel would have the originality to meet the incoming trains with a four-horse Concord coach, such as is inseparably associated with the Santa Fé Trail, instead of a ramshackle bus, they would soon have so many visitors piling into the New Mexican capital that they could not take care of them. But they are a dolce far niente folk, are the people of Santa Fé, and I expect that they will placidly continue along the same happy, easy, sleepy path that they have always followed. And perhaps it is just as well that they should.

A dwelling.

A street.

From a photograph copyright by Jess Nusbaum.

Interior of a room.

SANTA FÉ: THE MOST PICTURESQUE CITY BETWEEN THE OCEANS.

“They call me Santa Fé for short,” the New Mexican capital might answer if one inquired its name, “but my whole name is La Ciudad Real de la Santa Fé de San Francisco,” which, translated into our own tongue, means “The Royal City of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis.” It is some name—there is no denying that—but historically the town is quite able to live up to it. Fifteen years before the anchor of the Mayflower rumbled down off New England’s rocky coast, Juan de Oñate, an adventurous and gold-hungry gentleman of Spain, marching up from Mexico, had raised over the Indian pueblo which had occupied this site from time beyond reckoning the banner of Castile. In 1680 came the great Indian revolt; the Spanish soldiers and settlers were surprised and massacred and the brown-robed friars were slain on the altars of the churches they had built. For twelve years the Pueblos ruled the land. Then came De Vargas, at the head of a column of steel-capped and cuirassed soldiery and, after a ferocious reckoning with the Indians, retook the city in the name of his Most Catholic Majesty of Spain. With the overthrow of Spanish dominion in Mexico, the City of the Holy Faith became the northernmost outpost of the Mexican Republic, and Mexican it remained until that August morning in 1846 when General Kearney and his brass-helmeted dragoons clattered into its plaza and raised on the palace flagstaff a flag that was never to come down. That episode is commemorated by a marble shaft which rises amid the cottonwoods on the historic plaza. On its base are carved the words in which General Kearney proclaimed the annexation of New Mexico to the United States:

“We come as friends to make you a part of the representative government. In our government all men are equal. Every man has a right to serve God according to his conscience and his heart.”

At the other end of the plaza another monument marks the end of the famous Santa Fé Trail, over which, in prairie-schooners and Concord coaches and on the backs of mules and horses, was borne the commerce of the prairies. Santa Fé was to the historic trail of which it was the end what Bagdad is to the caravan routes across the Persian desert. No sooner would the lead team of one of these mile-long wagon-trains top the surrounding hills than word of its approach would spread through Santa Fé like wildfire. “Los Americanos! Los Carros! La Caravana!” the inhabitants would call to one another as they turned their faces plazaward, for the coming of a wagon-train was as much of an event as is the arrival of a steamer at a South Sea island. By the time that the first of the creaking, white-topped wagons, with its five yoke of oxen, had come to a halt before the custom-house, every inhabitant of the town was in the streets. A necessary preliminary to any trading was for the chief trader to make a call of ceremony upon the Spanish governor and, after a laboured interchange of salutes and compliments, to pay him the enormous toll of five hundred dollars per wagon imposed by the Spanish government upon wagon-trains coming from the United States. It came out of the pockets of the Spaniards in the end, however, for the American traders simply added it to the prices which they charged for their merchandise, which were high enough already, goodness knows: linen brought four dollars a yard, broadcloth twenty-five dollars a yard, and everything else in proportion. It is no wonder that the traders of the plains often retired as wealthy men. Stephen B. Elkins came to New Mexico, where he was to found his fortune, as bull-whacker in a wagon-train; one of the traders, Bent by name, came in time to sit himself in the governor’s palace in Santa Fé; and Kit Carson’s earlier years were spent in guiding these commercial expeditions. With the driving of the last spike in the Union Pacific Railroad, however, the importance of Santa Fé as a half-way house on the overland route to California vanished, and since then it has dwelt, contentedly enough, in its glorious climate and its memories of the past.

Up the Cañon of the Santa Fé, over the nine-thousand-foot Dalton Divide, and down into the Cañon of the Macho, several hundred gentlemen, in garments of a somewhat conspicuous pattern provided by the State, are building what will in time take rank as one of the world’s great highways. It is to be called the Scenic Highway, and when it is completed it will form a section of the projected Camino Real from Denver to El Paso. It promises to be to the American Southwest what the Sorrento-Amalfi Drive is to southern Italy and the famous Corniche Road is to the south of France. By means of switchbacks—twenty-two of them in all—it will wind up the precipitous slopes of the great Dalton Divide, twist and turn among the snow-capped titans of the Sangre de Cristo Range, skirt the edges of sheer precipices and dizzy chasms, drop down through the leafy solitudes of the Pecos Forest Reserve, and then stretch its length across the rolling uplands toward Taos, the pyramid-city of the Pueblos.

Within a hundred-mile radius of Santa Fé are three of the most wonderful “sights” in this or any other country: the hill-city of Acoma, the pyramid-pueblo of Taos (both of which are described at length in the succeeding chapter) and the Pajarito National Park. The Pajarito (in Spanish, remember, the j takes the sound of h) provides what is unquestionably the richest field of archæological research in the United States, the remains of the inconceivably ancient civilisation with which it is literally strewn, bearing much the same relation to the history of the New World that the ruins of Upper Egypt do to that of the Old. To reach the Pajarito, where the ruins of the cave people exist, you can ride or drive or motor. As the distance from Santa Fé is only about forty miles, if you are willing to get up with the chickens you can make it in a single day. Comfortable sleeping quarters and excellent meals can be had at the hospitable ranch-house of Judge Abbott, or, if you prefer, you can take along a pair of blankets and some provisions and sleep high and dry in a cave once occupied by one of your very remote ancestors. The very courteous gentlemen in charge of the American School of Archæology at Santa Fé are always glad to furnish information regarding the best way to enter the Pajarito. Twenty odd miles north of Santa Fé and, debouching quite unexpectedly upon the flat summit of a mesa, you look down upon the iridescent ribbon which is the Rio Grande as it twists and turns between the sheer, smooth walls of chalky rock which form the sides of White Rock Cañon. Coming into this great gorge at right angles are the smaller cañons—chief among them the one known as the Rito de los Frijoles—in whose precipitous walls the cave folk hewed their homes. Some of these smaller cañons are hundreds of feet above the bed of the Rio Grande, with openings barely wide enough to let the mountain streams fall through into the river below.

You must picture the Rito de los Frijoles as an immensely long and narrow cañon—so narrow that Rube Marquard could probably pitch a stone across—with walls as steep and smooth and twice as high as those of the Flatiron Building. Then you must picture the lower face of this rocky wall as being literally honeycombed by thousands—and when I say thousands I do not mean hundreds—of windows and doors and port-holes and apertures and other openings to caves hollowed from the soft rock of the cliffs. It is a city of the dead, silent as a mausoleum, mysterious as the lines of the hand, older than recorded history. This once populous city consisted of a single street, twelve miles long, its cave-dwellings, which were reached by ladders or by steps cut in the soft tufa, rising above each other, tier on tier, like some Gargantuan apartment building. Such portions of the face of the cliff as are not perforated with doors and windows are embellished with pictographs, many of them in an extraordinary state of preservation, which, if the sight-seeing public only knew it, are as interesting and far more perplexing than the wall-paintings in the Tombs of the Kings at Thebes. On the floor of the valley the archæologists have laid bare the ruins of a circular community house which, when viewed from above, bears a striking resemblance to the ancient Greek theatre at Taormina, while on the Puyé to the north a communal building of twelve hundred rooms—larger than the Waldorf-Astoria—has been excavated. Farther down the Rito is the stone circle or dancing floor to which the prehistoric young folk descended to make merry, while their parents kept an eye on them from their houses in the cliff. (I doubt not that, when the sun began to sink behind the Jemez, some skin-clad mother would lean from the window of her fifth-story flat and shrilly call to her daughter, engrossed in learning the steps of the prehistoric equivalent of the tango on the dancing floor below: “A-ya, come up this minute! You hear me? Your paw’s just come home with a dinosaur and he wants it cooked for supper.”) Three miles up the cañon, half a thousand feet up the face of the cliff, is the arched ceremonial cave where, secure from prying eyes, this strange people performed their still stranger rites. Thanks to the energy of the American Archæological Society, this cave has been restored to the same condition in which it was when prehistoric lodge members worked their mysterious degrees and made the quaking initiates ride the goat. Though it is the aim of the society to year by year restore portions of the Rito until the whole cañon has returned to its original condition, such difficulty has been experienced in obtaining the necessary funds that at the present rate of progress it will take a century to effect a complete restoration. Yet our millionaires pour out their wealth like water to promote the excavation and restoration of the ruins of alien peoples in other lands. Though carloads of pottery and utensils have been carted away to enrich museums and private collections, the surface of the Pajarito has been scarcely scratched, more than twenty thousand communal caves and dwellings remaining to tempt the seekers of lost cities. Where did the inhabitants of this strange city go—and why? What swept their civilisation away? When did the age-old silence fall? These are questions which even the archæologists do not attempt to answer. All that they can assert with any degree of certainty is that the caves which underlie the communal dwellings in the Pajarito yield ample evidence of having been occupied by human beings in the days of the lava flow, when the mastodon and the dinosaur roamed the land and the world was very, very young.

“The arched ceremonial cave where ... this strange people performed their still stranger rites.”

“The archæologists have laid bare the ruins of a circular community house.”

REMAINS OF AN ANCIENT CIVILISATION.

Of the three great elemental industries of New Mexico—cattle raising, sheep raising, and mining—cattle raising was the first and, more than any other, gave colour to the country. The early Spanish and Mexican settlers were cow-men, and the old Sonora stock, “all horns and backbone,” may still be seen on some of the interior ranges, though they are now almost a thing of the past. Then came the great wagon-trains of Texans, California bound, many of whom, attracted by the wealth of pasturage, stopped off and turned their long-horned cattle out on the grass-grown desert. As Texas and the Middle West became fenced and civilised, the old-time cattlemen drove their herds farther and farther toward the setting sun. In those days there were no sheep to compete for the pasture; mountains and desert were clothed with grass so rich and long that they looked as though they were upholstered in green velvet; there was not a strand of barbed wire between the Pecos and the Colorado. New Mexico was indeed the cow-man’s paradise. Though the range has in many places been ruined by droughts and overstocking; though a woolly wave has encroached upon the lands which the cow-man had regarded as inalienably his own, there are, nevertheless, close to a million head of cattle within the borders of the State, by far the greater part of which are Herefords and Durhams, for the imported stock has increased the cow-man’s profits out of all proportion to the initial expense.

Feeding with equal right and freedom upon the same public domain are upward of five million head of sheep, for New Mexico is the home of the wool industry in America. The early Spanish settlers kept large flocks of the straight-necked, coarse-wooled Mexican sheep in the country around Santa Fé, and from them the Navajos and Moquis, those industrious weavers of blankets and workers in silver, soon stole or bartered for enough to start a sheep business of their own, it being said that a third of all the sheep in the State are now owned by Indians. Unlike cattle, sheep, in cool weather, can exist without water for a month at a time; so, when the desert turns from yellow to green in the spring, they drift out over it in great flocks which look for all the world like fleecy clouds. Each flock, which usually consists of several thousand sheep, is attended by a herder and his “rustler,” who cooks, packs in supplies, and brings water in casks from the nearest stream for the use of the herder and his dogs, the juicy browse providing all the moisture that the sheep require.

Owing to its warm, dry weather, New Mexico is one of the earliest shearing stations in the world, the work beginning the latter part of January and lasting until the first of May. In this time enough wool is clipped to supply a considerable portion of the people of the United States with suits and blankets. Until quite recently the shearing of the wool was a long and tedious task, even the more expert hand shearers seldom being able to average more than sixty or seventy fleeces a day. When machine shearing was introduced into New Mexico a few years age, however, this daily average was promptly doubled. Sheep-shearers are probably the best-paid and hardest-working class of men in the world, receiving from seven to eight and a half cents a head and averaging one hundred and twenty-five sheep a day. The best of them, however, shear from two to three hundred sheep in a single day, the record, I believe, being three hundred and twenty-five. As the shearing season only lasts through six months of the year, during which time they must travel from Texas to Montana, the unionised shearers demand and receive high wages, some of them making as much as twenty dollars a day. Yet, in spite of this and of the grazing fee of six cents a head for all sheep that feed on forest reserves, it is safe to say that the wool-growers are the most prosperous men in New Mexico.

The social fabric of New Mexico is a curious blending of Mexicans, Indians, and Americans. Of these elements the Mexicans are by far the most numerous, their customs, costumes, and language lending a decidedly Spanish flavour to the country. Living for the most part in scattered settlements along the mountain streams or in their own quarters in the towns, they enjoy a lazy, irresponsible, and not uncomfortable existence in return for their humble labour, not differing materially, either in their mode of life, manners, or morals, from their kinsmen below the Rio Grande. Shiftless, indolent, indifferently honest, the peons of New Mexico, like the South African Kaffirs and the Egyptian fellaheen, are nevertheless invaluable to the welfare of the State, for they perform practically all the labour on the ranches, mines, and railways. Politically they are an element to be reckoned with, about seventy-five per cent of the population of Santa Fé being Mexicans, while sixty per cent of the State Legislature is from the same race. As a result of this Latin preponderance in the population, practically all Americans in New Mexico are compelled to have at least a working knowledge of Spanish, which is really the lingua franca of the country, it being by no means unusual to find one who speaks it better than the Mexicans themselves. Owing to the great influx of settlers during the last few years, the Mexican proportion of the population has been greatly reduced, as is confirmed by the increasing use of the English language and of English newspapers.

One of the strangest religious sects in the world—the Penitentes—are recruited from the Mexican element of the population. Although this dread form of religious fanaticism has its centre in the region about San Mateo, it permeates peon life in every quarter of the State. For the Penitente is not an Indian; he is a Mexican. The Indians of the Pueblos repudiate Penitente practices. Neither is the Penitente a Catholic, for the Church has fought his terrible rites tooth and nail, though thus far it has fought them in vain. He is really a grim survivor of those secret orders whose fanaticism and religious excesses became a byword even in the calloused Europe of the Middle Ages. The sect is divided into two branches: the Brothers of Light—La Luz—and the Brothers of Darkness—Las Tinieblas. Though they hold secret meetings with more or less regularity throughout the year in their lodges or morados, they are really active only during the forty days of Lent. During that period both men and women flog their naked backs with scourges of aloe fibre, wind their limbs with wire or rope so tightly as to stop the circulation, lie for hours at a time on beds of cactus, make pilgrimages to mountain shrines with their unstockinged feet in shoes filled with jagged flints, stagger torturing miles across the sun-baked desert under the weight of enormous crosses, while on Good Friday this carnival of torture culminates in one of their number, chosen by lot, actually being crucified. It has been a number of years, however, since a Penitente has died on the cross, for, since the law came to New Mexico, they have found it wiser to fasten their willing victim to the cross with rope instead of nails. Though sporadic efforts have been made to break up the sect, they have thus far been unsuccessful, as it is no secret that many men high in the political life of New Mexico bear on their backs the tattooed cross which is the symbol of the order.

Though the growth of the white population has heretofore been slow, it has begun to increase by leaps and bounds with the development of irrigation. Though New Mexico now contains representatives from every State in the Union and from pretty much every country in the world, the average run of society exhibits a tendency toward high-crowned hats that shows the dominating influence of Texas. They are, I think, the most hospitable folk that I have ever met; they are tolerant of other people’s opinions; have a tendency to ride rather than walk; are ready to fight at the drop of the hat; hate to count their money; lie only for the sake of entertainment; like a big proposition; and know how to handle it—there you have them, the gentlemen of New Mexico. But don’t go out to New Mexico, my Eastern friends, with the idea that you can butt into society with the aid of a good cigar—because you can’t. They are a free-born, free-living, free-speaking folk, are the dwellers out in the back country where the desert meets the mountains and the mountains meet the sky, and they don’t give a whoop-and-hurrah whether you come or stay away.

Such, in brief, bold outline, is the New Mexico of to-day. I have tried to paint you a picture, as well as I know how, of the progress, potentialities, and prospects of this, the youngest but one of the sisterhood of States. Though New Mexico, as a Territory, was willing enough to be a synonym for Indian villages and snake-dances and cavorting cowboys, the State of New Mexico stands for something very different indeed. Though it welcomes the tourists who come-look-see-spend-go, it prefers the settlers who are prepared to stay and make it their home. Unlike its sister State of Arizona, New Mexico does not suffer from that greatest of privations—lack of water—for the mountain-flood waters that now go to waste would store great reservoirs, there is the flow of numerous streams and river systems, and below the surface are artesian belts of water waiting only to be tapped by the farmer’s well. That the soil, once watered, is very fertile is best proved by the orchards, gardens, and meadows which cover the valleys of the Mimbres and the Pecos. Ten years ago the cattlemen of New Mexico used to say that it took “sixty acres to raise a steer”; to-day, thanks to irrigation, a single acre of alfalfa does the business. In gold, silver, coal, and copper the State is very rich—the largest copper mine in the world is at Silver City—while its turquoise deposits surpass those of Persia. And the people are as big-hearted and broad-minded and open-handed as you will find anywhere on earth. Taking it by and large, therefore, a man with some experience, a little capital, plenty of energy and ambition, and an intimate acquaintance with hard work should go a long way in New Mexico. He would find down there a big, new, unfenced, up-and-doing country and a set of sun-bronzed, iron-hard, self-reliant men of whom any country might be proud. These men are the modern conquistadores, for they have conquered sun and sand. To-day they are only commonplace farmers, but, when history has granted them the justice of perspective, they will be called the Pioneers.

II

THE SKYLANDERS

II

THE SKYLANDERS

Six minutes after midnight the mail-train came thundering out of nowhere. With hissing steam and brakes asqueal it paused just long enough for me to drop off and then roared on its transcontinental way again to the accompaniment of a droning chant which quickly dropped into diminuendo, its scarlet tail lamps disappearing at forty miles an hour, leaving me abandoned in the utter darkness of the desert. The Casa Alvarado at Albuquerque, with its red-shaded candles and snowy napery, where I had dined only four hours before, seemed very far away. Some one flashed a lantern in my face and a voice behind it inquired:

“Are you the gent that’s goin’ to Acoma?”

“I am,” said I, “if I can get there.”

“Well, I reckon you’ll get there all right, seein’ as how the trader at Laguna’s sent a rig over for you. Bob made a little money on a bunch o’ cattle a while back and he’s been pretty damned independent ever since ’bout takin’ folks over to Acoma. Says it’s too hard on his horses. But when Bob says he’ll do a thing he does it. Hi, Charlie!” he shouted, “you over there?”

A guttural affirmative came out of the blackness. As the loquacious station agent made no offer to light my footsteps, I cautiously picked my way across the rails, slid down a steep embankment into a ditch, scrambled out of it, and descried before me the vague outlines of a ramshackle vehicle drawn by a pair of wiry, unkempt ponies.

“How?” grunted the driver, who, as my eyes became accustomed to the darkness, I saw was an Indian, his hair, plaited in two long braids with strands of vivid flannel interwoven, hanging in front of his shoulders, schoolgirl fashion. I clambered in, the Indian spoke to his ponies, and, breaking into a lope, they swung off across the desert, the wretched vehicle lurching and pitching behind them.

It is an unforgettable experience, a ride across the New Mexican desert in the night-time. The sky is like purple velvet and the stars seem very near. The silence is not the peaceful stillness that comes with nightfall in settled regions, but the mysterious, uncanny hush that hangs over other ancient and deserted lands—Upper Egypt, for example, and Turkestan. Our way was lined with dim, fantastic shapes whose phantom arms seemed to warn or beckon or implore, but which, in the prosaic light of morning, resolved themselves into clumps of piñon, and mesquite, and prickly-pear. The ponies shied suddenly at a stirring in the underbrush—probably a rattlesnake disturbed—and in the distance a coyote gave dismal tongue. Slipping and sliding down a declivity so abrupt that the axles were level with the ponies’ backs, we rattled across the stone-strewn bed of an arroyo seco, as they term a dried-up watercourse in that half-Spanish region, and clattered into a settlement whose squat, flat-roofed hovels of adobe, unlighted and silent as the houses of Pompeii, showed dimly on either hand.

“Laguna?” I inquired.

“Uh-huh,” responded my taciturn companion, pulling up his ponies sharply before a dwelling considerably more pretentious than the rest. “Trader’s,” he added laconically.

As, stiff, chilled, and weary, I scrambled down, the door swung open to reveal a lean figure in shirt and trousers, silhouetted by the light from a guttering candle.

“I’m the trader,” said he. “I reckon you’re the party we’ve been expectin’. We ain’t got much accommodation to offer you, but, such as it is, you’re welcome to it. I’m afeard my youngsters’ll keep you awake, though. I’ve got six on ’em an’ they’ve all got the whoopin’-cough, so me an’ my old woman hain’t had a chanct to shet our eyes for the last week.”

It wasn’t the cough-harassed children who kept me wide-eyed and tossing through the night, however. It was Sheridan, I think, who remarked that had the fleas of a certain bed upon which he once slept been unanimous, they could easily have pushed him out. Had the tiny hordes which were in possession of my couch had an insect Kitchener to organise and lead them, I should certainly have had to spend the night upon the floor. I learned afterward that the Indians of the neighbouring pueblos have a name for Laguna which, in the white man’s tongue, means “Scratch-town.”

From Laguna to Acoma is a four hours’ drive across the desert. It is very rough and more than once I feared that I should require the services of an osteopath to rejoint my vertebræ. And it is inconceivably dusty, the ponies kicking up clouds of fine, shifting sand which fills your eyes and nose and ears and sifts through your garments until you feel as though you were covered with sandpaper instead of skin. The sun beats down until the arid expanse of the desert is as hot as the whitewashed base of a railway-station stove at white heat. Everything considered, it is not the sort of a drive that one would choose for pleasure, but it is a very wonderful drive nevertheless, for the New Mexican desert is a kaleidoscope of colour. It is a land of black rocks and orange sand, flecked with discouraged, hopeless-looking clumps of sage-green vegetation; of violet, and amethyst, and purple mountain ranges; and overhead a sky of the brightest blue you will find anywhere outside a wash-tub. The cloud effects are the most beautiful I have ever seen, great masses of fleecy cirrus drifting lazily, like flocks of new-washed sheep, across the turquoise sky. Everywhere the colours are splashed on with a barbaric, almost a theatrical, touch. It is a regular back-drop of a country; its scenery looks as though it should have been painted on a curtain. When a party of Indians, with scarlet handkerchiefs twisted about their heads pirate fashion, lope by astride of spotted ponies, the illusion is complete. “You’re not really in New Mexico, you know,” you say to yourself. “This is much too theatrical to be real. You’re sitting in an orchestra chair watching a play, that’s what you’re doing.”

From a photograph by A. C. Vroman.

THE LAND OF THE TURQUOISE SKY.

“Great masses of fleecy cirrus drifting lazily, like flocks of new-washed sheep, across the turquoise sky.”

Swinging sharply around the shoulder of a sand-dune, a mesa—a table-land of rock—reared itself out of the plain as unexpectedly as a slap in the face. The driver pointed unconcernedly with his whip. “La Mesa Encantada,” he grunted. The Enchanted Mesa! Was there ever a name which so reeked with mystery and romance? Picture, if you can, a bandbox-shaped rock, almost flat on top and covering as much ground as a good-sized city square, higher than the Times Building in New York and with sides almost as perpendicular, set down in the middle of the flattest, yellowest desert the imagination can conceive. Seen from the distance, it suggests the stump of an inconceivably gigantic tree—a tree a thousand feet in diameter and sawed squarely off four hundred and thirty feet above the ground. On one side it is as sheer and smooth as that face of Gibraltar which looks Spainward, and when the evening sun strikes it slantingly it turns the monstrous mass of sandstone into a pile of rosy coral. It is one of the most impressive things that I have ever seen. Solitary, silent, mysterious, redolent of legend and superstition, older than Time itself, it suggests, without in any way resembling, those Colossi of Memnon which stare out across the desert from ruined Thebes.

Those disputatious cousins Science and Tradition seem to have agreed for once that the original Acoma stood on the top of the Mesa Encantada, or Katzimo, as the Indians call it, in the days when the world was very young. Ever since Katzimo first attracted scientific attention the archælogists have quarrelled like cats and dogs over this question of whether it had ever been inhabited, just as they are quarrelling in Palestine as to the site of Calvary. A few years ago the Smithsonian Institution, desirous of settling the controversy for good and all, despatched to New Mexico a gentleman of an inquiring turn of mind, who succeeded in performing the supposedly impossible feat of scaling the sheer cliffs which, from time beyond reckoning, have guarded the secret of the mesa. On the plateau at the top he found fragments of earthenware utensils, which would seem to prove quite conclusively that it had been inhabited in long-past ages by human beings, thus supporting the traditions which prevail among the Indians regarding this mighty monolith. Whether the Enchanted Mesa has ever been inhabited I do not know; no one knows; and, to tell the truth, it does not greatly matter. According to the legend current among the Pueblos, this island in the air was originally accessible by means of a huge, detached fragment leaning against it at such an angle that it formed a precarious and perilous ladder to the top. Its difficulty of access was more than compensated for, however, by its security from the attacks of enemies, whether on two feet or four, for Katzimo is supposed to have echoed to human voices in those dim and distant days when the mastodon and the dinosaur roamed the land. The Indian legend has it that, while the men of the tribe were absent on a hunting expedition and the able-bodied women were hoeing corn in the fields below, some cataclysm of nature—most probably an earthquake—jarred loose the ladder rock and toppled it over into the plain, leaving the town on the summit as completely cut off from human help as though it were on another planet. The women and children thus isolated perished miserably from starvation, and their spirits, so the Indians will assure you, still haunt the summit of Katzimo. On any windy night you can hear them for yourself, moaning and wailing for the help that never came. That is why it were easier to persuade a Mississippi darky to spend a night in a graveyard than to induce an Indian to linger in the vicinity of the Enchanted Mesa after dark.

From a photograph by A. C. Vroman.

“A bandbox-shaped rock, higher than the Times Building in New York and with sides almost as perpendicular.”

From a photograph by A. C. Vroman.

“The mesa on which the modern Acoma is perched might be likened to a gigantic billiard-table three hundred and fifty-seven feet high.”

ACOMA: SUPPOSED ANCIENT SITE AND PRESENT SITE.

The survivors of the tribe chose as the site of their new town the top of a somewhat lower mesa, three miles or so from their former home. If the Enchanted Mesa resembles a titanic bandbox, the mesa on which the modern Acoma is perched might be likened to a gigantic billiard-table, three hundred and fifty-seven feet high, seventy acres in area upon its level top, and supported by precipices which are not merely perpendicular but in many cases actually overhanging. It presents one of the most striking examples of erosion in the world, does Acoma, the sand which has been hurled against it by the wind of ages, as by a natural sand-blast, having cut the soft rock into forms more fantastic than were ever conjured up by Little Nemo in his dreams. Battlements, turrets, arches, minarets, and gargoyles of weather-worn, tawny-tinted rock rise on every hand. There are two routes to the summit and both of them require leathern lungs and seasoned sinews. One, called, if I remember rightly, the “Padre’s Path,” is little more than a crevasse in the solid rock, its ascent necessitating the vigorous use of knees and elbows as well as hands and feet, it being about as easy to negotiate as the outside of the Statue of Liberty. The other path, which is considerably longer, suggests the stone-paved ascent to some stronghold of the Middle Ages—and, when you come to think about it, that is precisely what it is—the resemblance being heightened by the massive battlements of eroded rock between which it winds and the strings of patient donkeys which plod up it, faggot-laden. Though of fair width near the bottom, it gradually narrows as it zigzags upward, finally becoming so slim that there is not room between the face of the cliff and the brink of the precipice for two donkeys to pass. It was at this inauspicious spot that I first encountered one of these dwellers in the sky—“skylanders” they might fittingly be called. He was a low-browed, sullen-looking fellow, with a skin the colour of a well-worn saddle and an expression about as pleasant as a rainy morning. His shock of coarse black hair had been bobbed just below the ears and was kept back from his eyes by the inevitable banda; his legs were encased in chaparejos of fringed buckskin, and his shirt tails fluttered free. He came jogging down the perilous pathway astride of a calico donkey and, with the background of rocks and sand, cut a very striking and savage figure indeed. “He’ll make a perfectly bully picture,” I said to myself, and, suiting the action to the thought, I unlimbered my camera and ambushed myself behind a projecting shoulder of rock. As he swung into the range of my lens I snapped the shutter. It was speeded up to a hundredth of a second, but in much less time than that he had dismounted and was coming for me with a club. I have read somewhere that the Acomas are a mild-mannered, inoffensive folk. Well, perhaps. Still, I was glad that I had in my jacket pocket the largest-sized automatic used by a civilised people, and I was still gladder when Man-That-Wouldn’t-Have-His-Picture-Taken, glimpsing its ominous outline through the cloth, moved sullenly away, shaking his stick and muttering sentiments which needed no translation. He was an artist in the way he laid on his curses, was that Indian. An army mule-skinner would have taken off his hat to him in admiration.

Of all the nineteen pueblos of New Mexico, Acoma is the most interesting by far. Indeed, I do not think that I am permitting my enthusiasm to get the better of my discrimination when I class it with Urga, Khiva, Mecca, the troglodyte town of Medenine in southern Tunisia, and Timbuktu as one of the half dozen most interesting semicivilised places in existence. Where else in all the world can you find a town hanging, as it were, between land and sky and reached by some of the dizziest trails ever trod by human feet; a town of many-floored but doorless dwellings, which have ladders instead of stairs and whose windows are of gypsum instead of glass; a town where the women build and own the houses and the men weave the women’s gowns; where the husbands take the names of their wives and the children the names of their mothers; where the belongings of a dead man are destroyed upon his grave and the ghosts are distracted so that his spirit may have time to escape; a town where religious mysteries, as incredible as those of voodooism and as jealously guarded as those of Lhasa, are performed in an underground chamber as impossible of access by the uninitiated as the Kaaba? Where else shall you find such a place as that, I ask you? Tell me that.

From a photograph by A. C. Vroman.

“The massive battlements of eroded rock between which it winds ... suggest the stone-paved ascent to some stronghold of the Middle Ages.”

From a photograph by A. C. Vroman.

“You gain access to the first floor of an Acoma dwelling precisely as you gain access to the hold of a ship.”

ACOMA AS IT IS TO-DAY.

Acoma has the unassailable distinction of being the oldest continuously inhabited town within our borders, though how old the archæologists have been unable to conjecture, much less positively say. Certain it is that it was ancient when the Great Navigator set foot on the beach of San Salvador; that it was hoary with antiquity when the Great Captain and his mail-clad men-at-arms came marching up from Vera Cruz for the taking of Mexico. One needs to be very close under its beetling cliffs before any sign of the village can be detected, as the houses are of the same color and, indeed of the same material as the rock upon which they stand and so far above the plain that, as old Casteñeda, the chronicler of Coronado’s expedition in 1540, records, “it was a very good musket that could throw a ball as high.” The lofty situation of the town and the effect of bleakness produced by the entire absence of vegetation and by the cold, grey rock of which it is built reminded me of San Marino, that mountain-top capital of a tiny republic in the Apennines, while in the startling abruptness with which the mesa rears itself out of the desert there is a suggestion of those strange monasteries of Metéora, perched on their rocky columns above the Thessalian plain. The village proper consists of three parallel blocks of houses running east and west perhaps a thousand feet and skyward forty. They are, in fact, primeval apartment-houses, each block being partitioned by cross-walls into separate little homes which have no interior communication with each other. Each of these blocks is three stories high, with a sheer wall behind but terraced in front, so that it looks like a flight of three gigantic steps. (At the sister pueblo of Taos, a hundred miles or so to the northward, this novel architectural scheme has been carried even further by building the houses six and even seven stories high and terracing them on all four sides so that they form a pyramid.) The second story is set well back on the roof of the first, thus giving it a broad, uncovered terrace across its entire front, and the third story is similarly placed upon the second. In Acoma, which has about seven hundred people, there are scarcely a dozen doors on the ground; and these indicate the abodes of those progressive citizens who, not satisfied with what was good enough for their fathers, must be for ever experimenting with some new-fangled device. Barring these cases of recent innovation, there are no doors to the lower floor, the only access to a house being by a rude ladder to the first terrace. If you are making a call on the occupants of the first story, you wriggle through a tiny trap-door in the floor of the second and literally drop in upon them—so literally that your hosts see your feet before they see your face. It is a novel experience ... yes, indeed. You gain access to the first floor of an Acoma dwelling precisely as you gain access to the hold of a ship—by climbing a ladder to the deck and then descending through a hatchway. If you wish to leave your visiting-card at the third-floor apartment or if you have a hankering to see the view from the topmost roof, you can ascend quite easily by means of queer little steps notched in the division walls. The ground floor is always occupied by the senior members of the family, the second terrace is allotted to the daughter first married, and the upper flat goes to the daughter who gets a husband next. If there are other married daughters they must seek apartments elsewhere or live with grandpa and grandma in the basement.

Most writers about Acoma seem to be particularly impressed with the cleanliness of its inhabitants and the neatness of their homes. I don’t like to shatter any illusions, but it struck me that the much-vaunted neatness of these people consisted mainly in covering their beds with scarlet blankets and whitewashing their walls. I have heard visitors exclaim enthusiastically as they peered in through an open doorway: “Why, I wouldn’t mind sleeping there at all.” They are perfectly welcome to so far as I am concerned. As for me, I much prefer a warm blanket and the open mesa. All of the Pueblo Indians are as ignorant of the elements of sanitation as a Congo black. If you doubt it, visit one of these sky cities on a scorching summer’s day when there is no wind blowing. As an old frontiersman in Albuquerque confided to me: “Say, friend, I’d ruther have a skunk hangin’ round my tent than to have to spend a night to leeward o’ one of them there Hopi towns.”

Civilisation has evidently found the rocky path to Acoma too steep to climb, for when I was there not a soul in the place spoke a word of English. There was a daughter of the village who had been educated at Carlisle—Marie was her name, I think—but she was away on a visit. Perhaps she couldn’t stand the loneliness of being the only civilised person in the community. That is one of the deplorable features incident to our system of Indian education. A youth is sent to Carlisle or Hampton or Riverside, as the case may be, and after being broken to the white man’s ways is sent back to his own people on the theory that, by force of example, he will alter their mode of living. But he rarely does anything of the sort, for his fellow tribesmen either resent his attempts to introduce innovations or treat him with the same contemptuous tolerance with which the hidebound residents of a country village regard the youth who is “college l’arned.” So, after a time, becoming discouraged by the futility of attempting to teach his people something that they don’t want to know, he either goes out into the world to earn his own livelihood as best he may or else he again leaves his shirt tails outside his breeches, daubs his face with paint on dance days, and, forgetting how to use a fork and napkin, goes back to the manners and usages of his fathers. But you mustn’t get the idea that Acoma is wholly uncivilised, for it isn’t. One household has an iron bed with large brass knobs, another boasts a rocking-chair, and a third possesses a sewing-machine. But the most convincing proof that these untutored children of the sky possess a strain of culture is in the fact that Acoma can boast no phonograph to greet the visitor with the raucous strains of “Every Little Movement” and “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.”

From a photograph copyright by Fred Harvey.

ACOMA HUNTER HOME FROM THE HUNT.