The Wonder Clock

Katharine Pyle

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

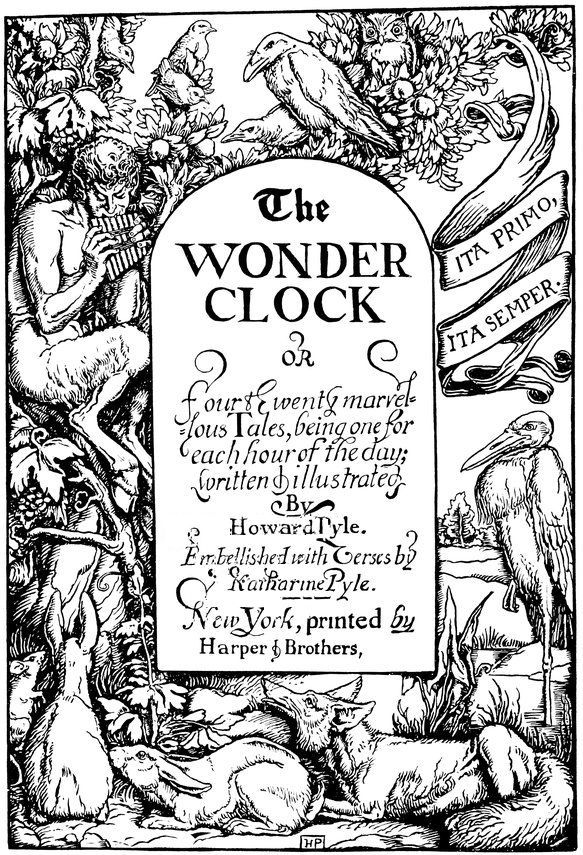

The

WONDER CLOCK

OR

four & twenty marvellous Tales, being one for each hour of the day; written & illustrated

PREFACE.

I put on my dream-cap one day and stepped into Wonderland.

Along the road I jogged and never dusted my shoes, and all the time the pleasant sun shone and never burned my back, and the little white clouds floated across the blue sky and never let fall a drop of rain to wet my jacket. And by and by I came to a steep hill.

I climbed the hill, though I had more than one tumble in doing it, and there, on the tip top, I found a house as old as the world itself.

That was where Father Time lived; and who should sit in the sun at the door, spinning away for dear life, but Time’s Grandmother herself; and if you would like to know how old she is you will have to climb to the top of the church steeple and ask the wind as he sits upon the weather-cock, humming the tune of Over-yonder song to himself.

“Good-morning,” says Time’s Grandmother to me.

“Good-morning,” says I to her.

“And what do you seek here?” says she to me.

“I come to look for odds and ends,” says I to her.

“Very well,” says she; “just climb the stairs to the garret, and there you will find more than ten men can think about.”

“Thank you,” says I, and up the stairs I went. There I found all manner of queer forgotten things which had been laid away, nobody but Time and his Grandmother could tell where.

Over in the corner was a great, tall clock, that had stood there silently with never a tick or a ting since men began to grow too wise for toys and trinkets.

But I knew very well that the old clock was the

so down I took the key and wound it—gurr! gurr! gurr!

Click! buzz! went the wheels, and then—tick-tock! tick-tock! for the Wonder Clock is of that kind that it will never wear out, no matter how long it may stand in Time’s garret.

Down I sat and watched it, for every time it struck it played a pretty song, and when the song was ended—click! click!—out stepped the drollest little puppet-figures and went through with a dance, and I saw it all (with my dream-cap upon my head).

But the Wonder Clock had grown rusty from long standing, and though now and then the puppet-figures danced a dance that I knew as well as I know my bread-and-butter, at other times they jigged a step I had never seen before, and it came into my head that maybe a dozen or more puppet-plays had become jumbled together among the wheels back of the clock-face.

So there I sat in the dust watching the Wonder Clock, and when it had run down and the tunes and the puppet-show had come to an end, I took off my dream-cap, and—whisk!—there I was back home again among my books, with nothing brought away with me from that country but a little dust which I found sticking to my coat, and which I have never brushed away to this day.

Now if you also would like to go into Wonderland, you have only to hunt up your dream-cap (for everybody has one somewhere about the house), and to come to me, and I will show you the way to Time’s garret.

That is right! Pull the cap well down about your ears.

Here we are! And now I will wind the clock. Gurr! gurr! gurr!

Table of Contents.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| I. | Bearskin | 1 |

| II. | The Water of Life | 15 |

| III. | How One Turned his Trouble to Some Account | 27 |

| IV. | How Three Went out into the Wide World | 39 |

| V. | The Clever Student and the Master of Black Arts | 49 |

| VI. | The Princess Golden-Hair and the Great Black Raven | 63 |

| VII. | Cousin Greylegs, the Great Red Fox, and Grandfather Mole | 77 |

| VIII. | One Good Turn Deserves Another | 89 |

| IX. | The White Bird | 105 |

| X. | How the Good Gifts were Used by Two | 121 |

| XI. | How Boots Befooled the King | 135 |

| XII. | The Step-mother | 149 |

| XIII. | Master Jacob | 161 |

| XIV. | Peterkin and the Little Grey Hare | 175 |

| XV. | Mother Hildegarde | 189 |

| XVI. | Which is Best | 203 |

| XVII. | The Simpleton and his Little Black Hen | 217 |

| XVIII. | The Swan Maiden | 229 |

| XIX. | The Three Little Pigs and the Ogre | 241 |

| XX. | The Staff and the Fiddle | 253 |

| XXI. | How the Princess’s Pride was Broken | 267 |

| XXII. | How Two Went into Partnership | 279 |

| XXIII. | King Stork | 291 |

| XXIV. | The Best that Life has to Give | 305 |

List of Illustrations.

| Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frontispiece. | ||

| Head-piece—Preface | v | |

| Head-piece—Table of Contents | vii | |

| Head-piece—List of Illustrations | ix | |

| ONE O’CLOCK | 1 | |

| Head-piece—Bearskin | 3 | |

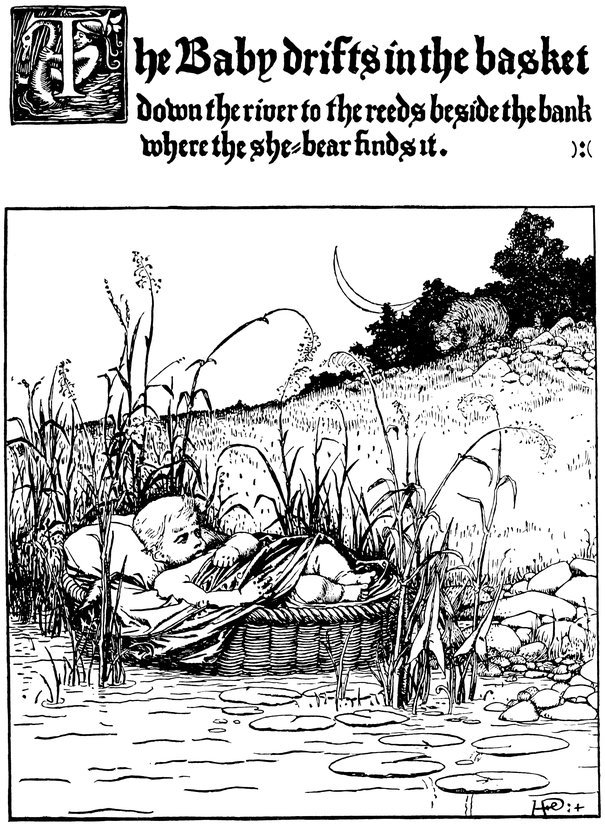

| The Baby drifts to the River’s Bank in the Basket | 5 | |

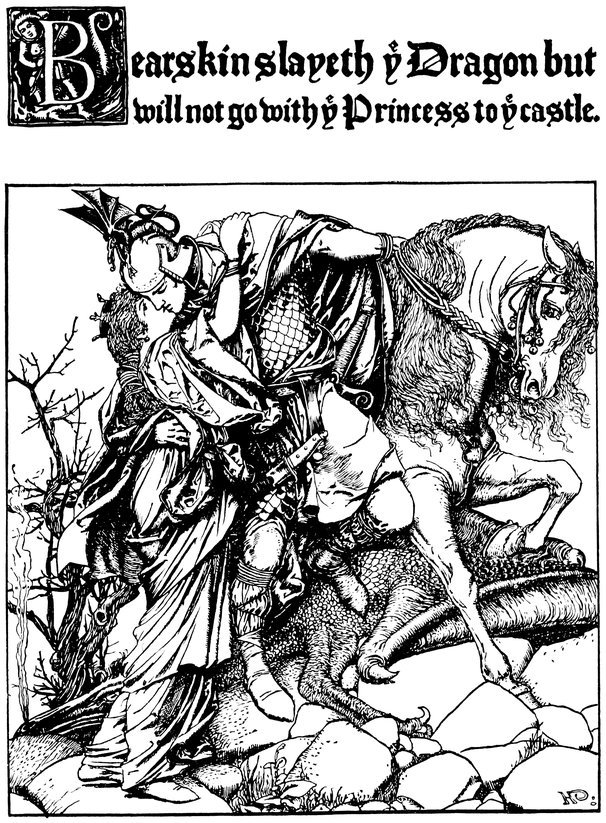

| Bearskin parts from the Princess | 9 | |

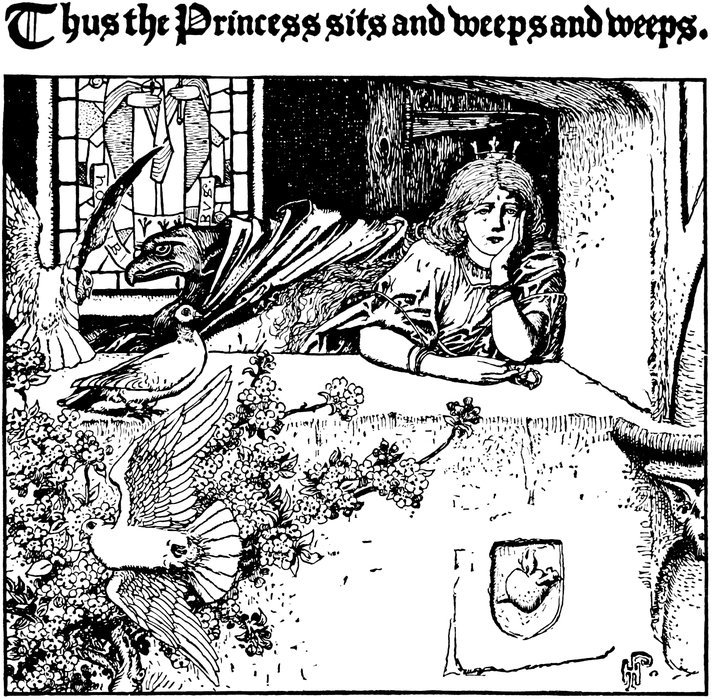

| The Princess weeps | 10 | |

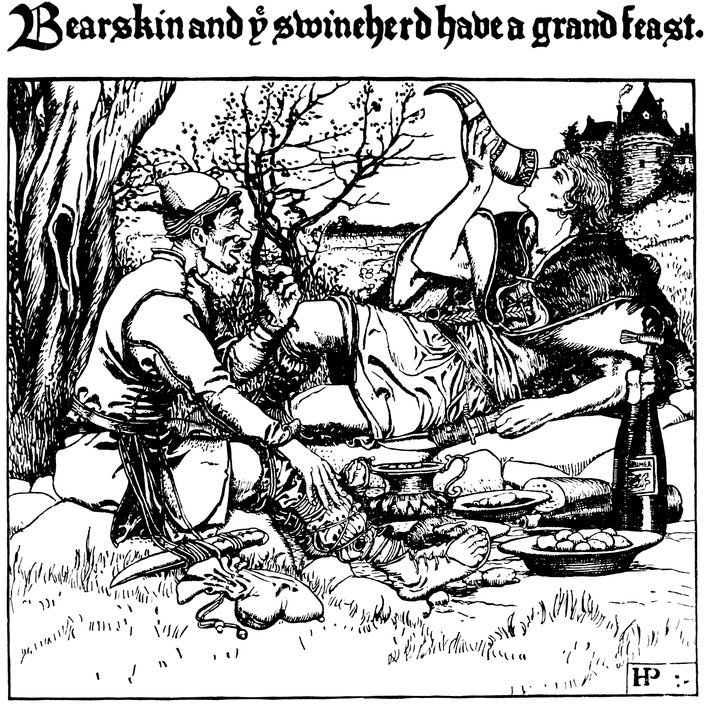

| Bearskin and the Swineherd feast together | 12 | |

| TWO O’CLOCK | 15 | |

| Head-piece—The Water of Life | 17 | |

| The King gazes upon the Picture | 19 | |

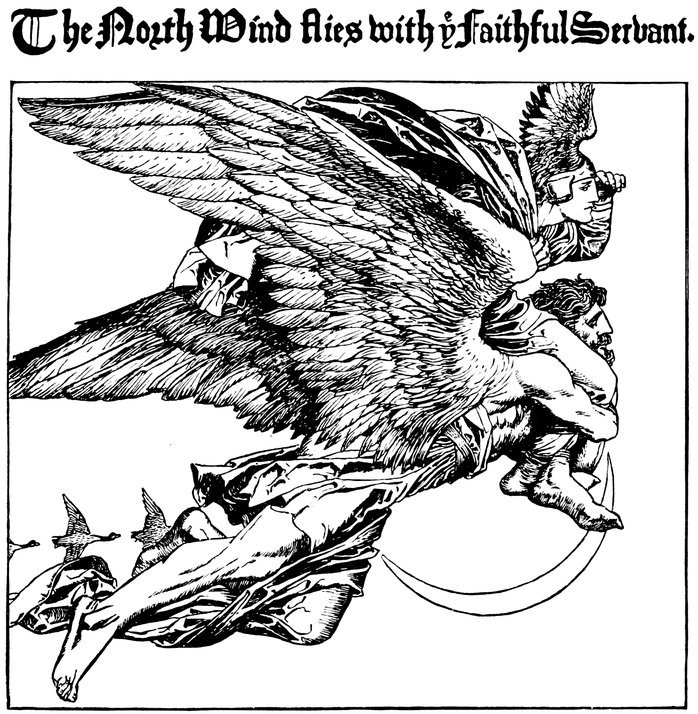

| The North Wind flies with the Faithful Servant | 21 | |

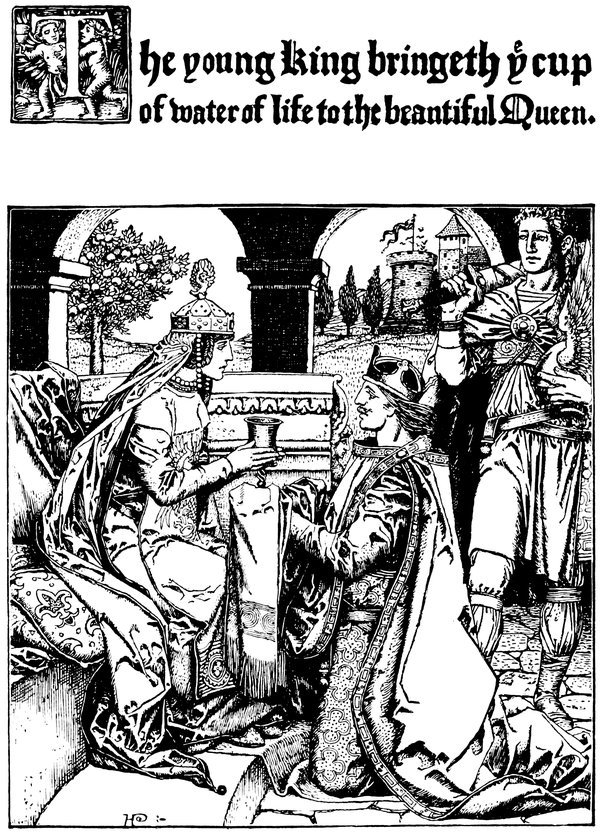

| The King brings the Water of Life to the Princess | 23 | |

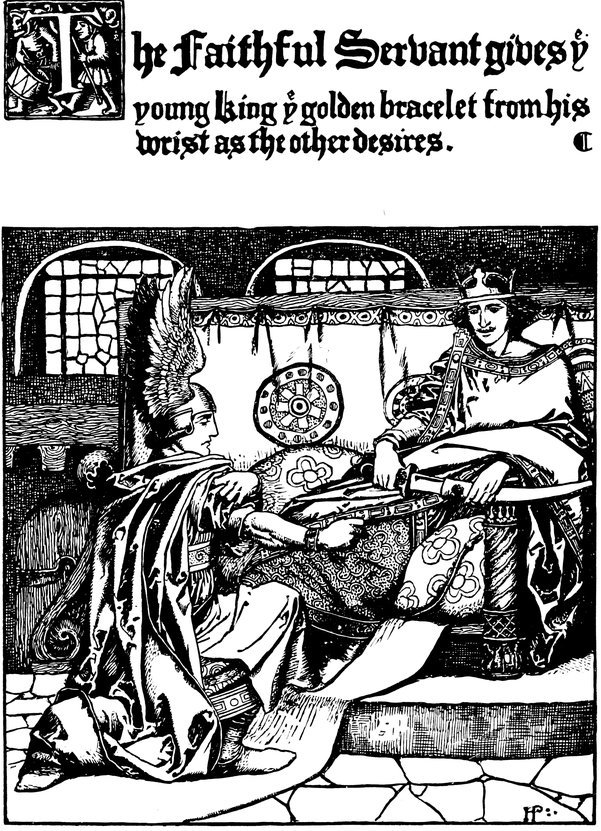

| The Faithful Servant gives the King his Golden Bracelet | 25 | |

| THREE O’CLOCK | 27 | |

| Head-piece—How One Turned his Trouble to Some Account | 29 | |

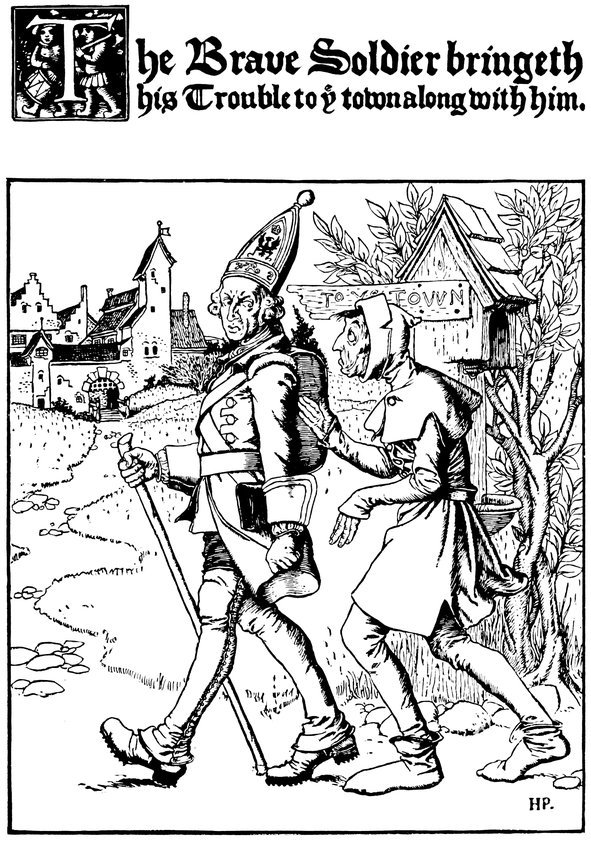

| The Soldier takes Trouble to Town | 31 | |

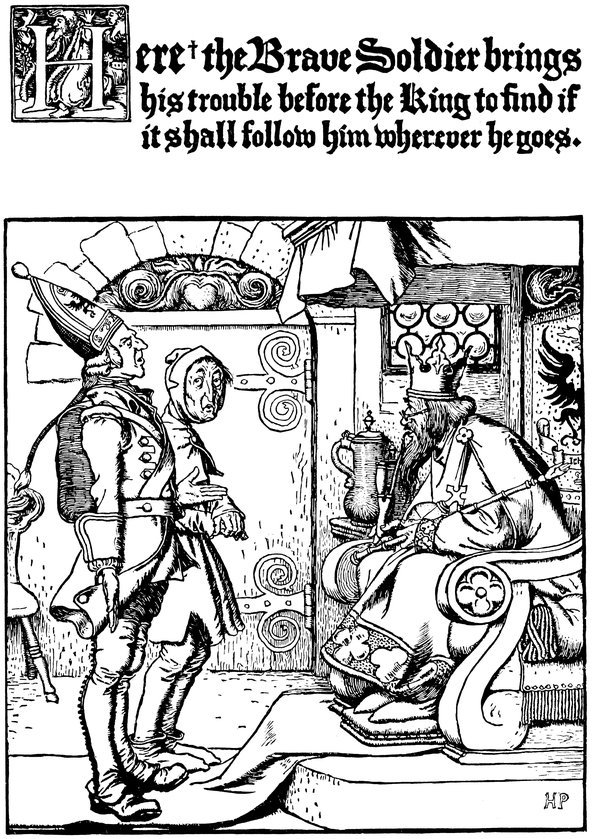

| The Soldier brings Trouble to the King | 33 | |

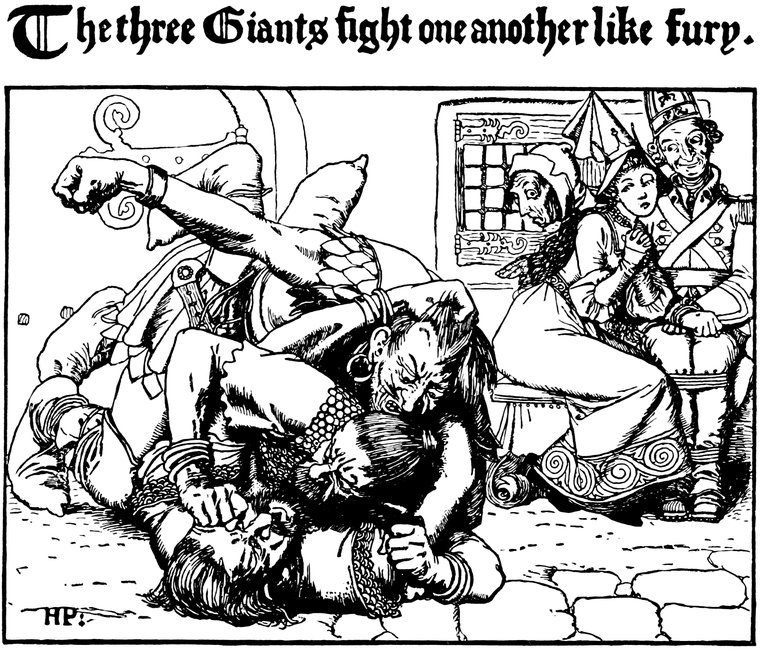

| The Giants fight one another | 35 | |

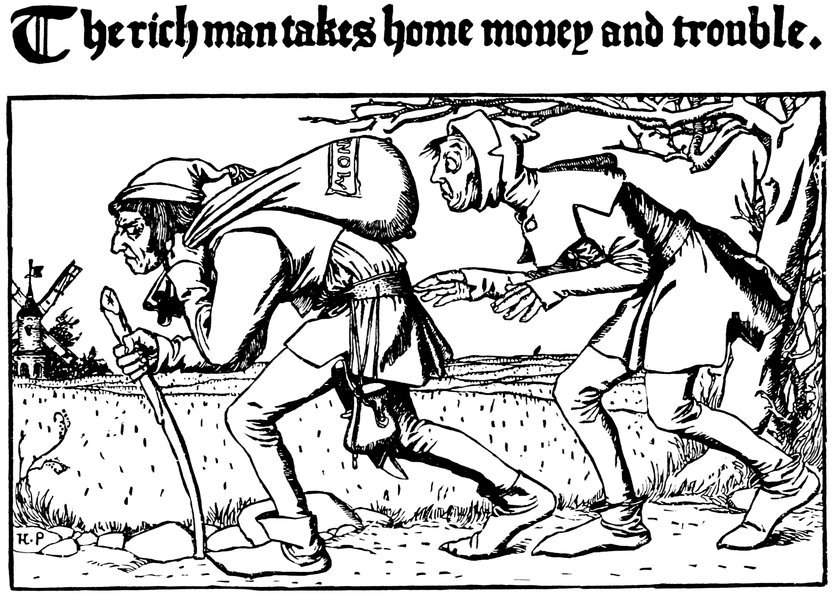

| The Rich Man takes Trouble home | 37 | |

| FOUR O’CLOCK | 39 | |

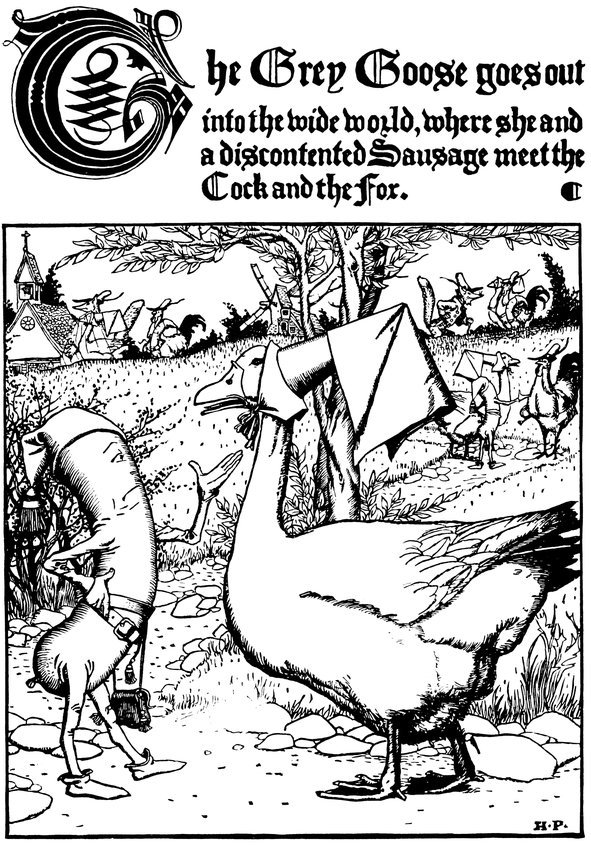

| Head-piece—How Three went out into the Wide World | 41 | |

| The Grey Goose meets the Sausage | 43 | |

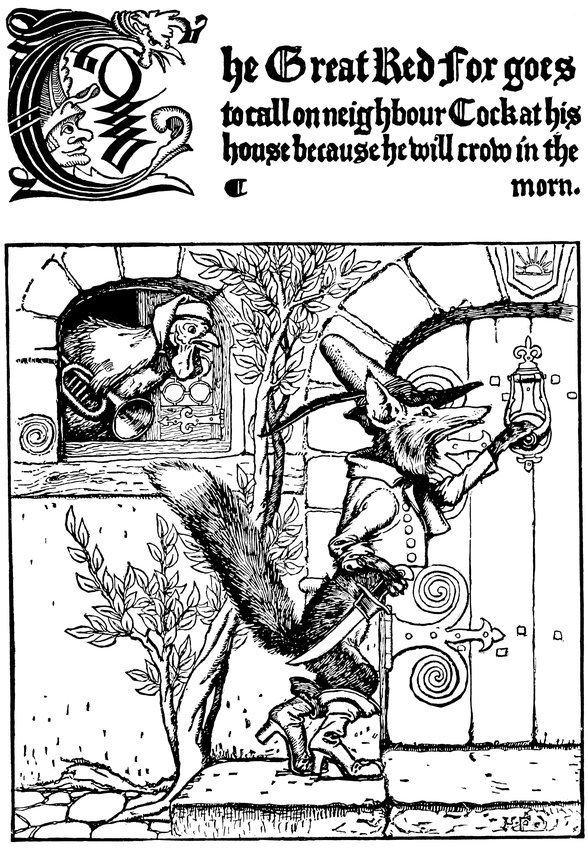

| The Great Red Fox calls upon the Cock | 45 | |

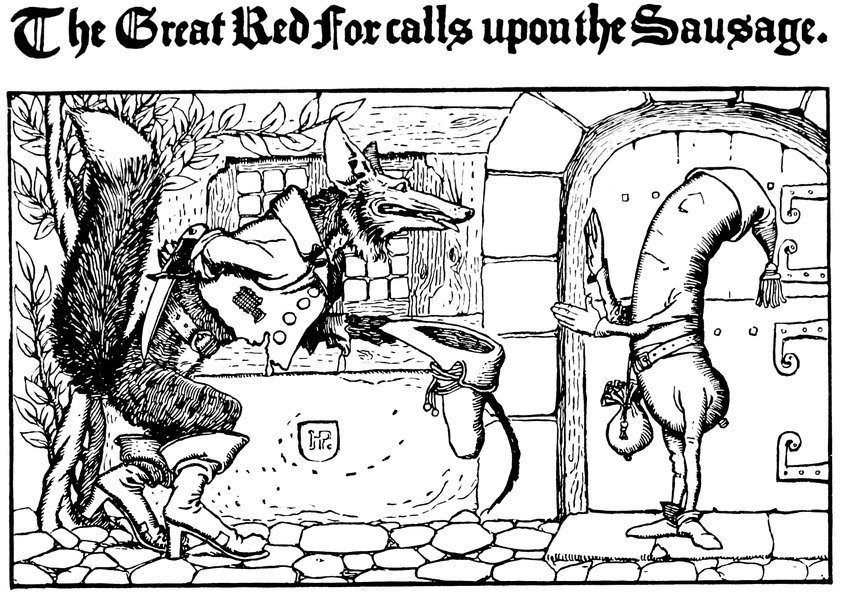

| The Great Red Fox calls upon the Sausage | 46 | |

| The Great Red Fox rests softly | 47 | |

| FIVE O’CLOCK | 49 | |

| Head-piece—The Clever Student and the Master of Black Arts | 51 | |

| A Princess walks beside the River | 53 | |

| The Clever Student and the Princess | 55 | |

| The Master of Black Arts and the Little Black Hen | 57 | |

| The Master of Black Arts is caught in his Tricks | 60 | |

| SIX O’CLOCK | 63 | |

| Head-piece—The Princess Golden-Hair and the Great Black Raven | 65 | |

| The King meets the Great Black Raven | 67 | |

| The Princess Golden-Hair drinks | 69 | |

| Princess Golden-Hair comes to Death’s Door | 71 | |

| The Princess finds the Prince | 75 | |

| SEVEN O’CLOCK | 77 | |

| Head-piece—Cousin Greylegs, the Great Red Fox, and Grandfather Mole | 79 | |

| Cousin Greylegs and the Great Red Fox go to the Fair | 81 | |

| Cousin Greylegs runs away with the Bag | 83 | |

| The Great Red Fox meets Grandfather Mole | 85 | |

| The Great Red Fox tries the Fire | 87 | |

| EIGHT O’CLOCK | 89 | |

| Head-piece—One Good Turn Deserves Another | 91 | |

| The Young Fisherman catches a Strange Fish | 93 | |

| The Young Fisherman and the Grey Master | 97 | |

| The Grey Master is caught in the Water | 101 | |

| The Princess finds the Young Fisherman | 103 | |

| NINE O’CLOCK | 105 | |

| Head-piece—The White Bird | 107 | |

| The Prince knocks at the Door of the Poor Little House | 109 | |

| The Prince finds the Three Giants sleeping | 111 | |

| The Prince finds the Sword of Brightness | 115 | |

| The White Bird knows the Prince | 119 | |

| TEN O’CLOCK | 121 | |

| Head-piece—How the Good Gifts were used by Two | 123 | |

| St. Nicholas knocks at the Rich Man’s Door | 125 | |

| St. Nicholas in the Poor Man’s House | 127 | |

| The Poor Man welcomes St. Christopher | 129 | |

| The Saints feast in the Rich Man’s House | 131 | |

| ELEVEN O’CLOCK | 135 | |

| Head-piece—How Boots befooled the King | 137 | |

| Peter goes to the King’s Castle | 139 | |

| Paul comes Home again | 141 | |

| The Old Woman smashes her Pots and Crocks | 143 | |

| The Councillor finds a Wisdom-sack | 145 | |

| TWELVE O’CLOCK | 149 | |

| Head-piece—The Step-mother | 151 | |

| The Step-daughter follows the Golden Ball | 153 | |

| The Young King brings the Maiden up from the Pit | 155 | |

| The Step-mother bewitches the Young Queen | 157 | |

| The Young King caresses the White Dove | 159 | |

| ONE O’CLOCK | 161 | |

| Head-piece—Master Jacob | 163 | |

| Master Jacob brings his Fat Pig to Town | 165 | |

| Master Jacob and his Black Goat | 167 | |

| The Three Cronies and the Black Goat | 171 | |

| Master Jacob meets the Three Cronies | 173 | |

| TWO O’CLOCK | 175 | |

| Head-piece—Peterkin and the Little Grey Hare | 177 | |

| Peterkin in his Fine Clothes | 179 | |

| Peterkin carries away the Giant’s Goose | 183 | |

| Peterkin brings the Silver Bell to the King | 185 | |

| Peterkin combs the Giant’s Hair | 187 | |

| THREE O’CLOCK | 189 | |

| Head-piece—Mother Hildegarde | 191 | |

| The Princess comes to Mother Hildegarde’s Door | 193 | |

| The Princess looks into the Jar | 195 | |

| The Wood-pigeons feed the Princess | 197 | |

| Mother Hildegarde carries away the Baby | 199 | |

| FOUR O’CLOCK | 203 | |

| Head-piece—Which is Best? | 205 | |

| The Rich Brother leaves the Poor Brother in Blindness | 207 | |

| The Poor Man finds the Little Door | 209 | |

| The Poor Man finds that which is the Best | 211 | |

| The Rich Man finds that which he Deserves | 213 | |

| FIVE O’CLOCK | 217 | |

| Head-piece—The Simpleton and his Little Black Hen | 219 | |

| Caspar starts to Town with his Little Black Hen | 221 | |

| Caspar finds a Bag of Money | 223 | |

| Three of them share the Money | 225 | |

| Caspar rides to the King’s Castle | 227 | |

| SIX O’CLOCK | 229 | |

| Head-piece—The Swan Maiden | 231 | |

| The Swan carries the Prince on its Back | 233 | |

| The Prince comes to the Three eyed Witch’s House | 235 | |

| The Swan Maiden helps the Young Prince | 237 | |

| The Witch and the Woman of Honey and Meal | 239 | |

| SEVEN O’CLOCK | 241 | |

| Head-piece—The Three Little Pigs and the Ogre | 243 | |

| The Ogre meets the Three Little Pigs in the Forest | 245 | |

| The Ogre climbs the Tree | 247 | |

| The Ogre shuts his Eyes and counts | 249 | |

| The Ogre sticks fast in the Window | 251 | |

| EIGHT O’CLOCK | 253 | |

| Head-piece—The Staff and the Fiddle | 255 | |

| The Fiddler helps the Old Woman | 257 | |

| The Fiddler and the Dwarf | 259 | |

| The Fiddler finds the Princess | 261 | |

| The Fiddler and the Little Black Mannikin | 263 | |

| NINE O’CLOCK | 267 | |

| Head-piece—How the Princess’s Pride was broken | 269 | |

| The Gooseherd plays with the Golden Ball | 271 | |

| The King peeps over the Hedge | 273 | |

| The Princess takes her Eggs to Market | 275 | |

| The Princess knows the Young King | 277 | |

| TEN O’CLOCK | 279 | |

| Head-piece—How Two Went into Partnership | 281 | |

| The Great Red Fox goes to the Store-house | 283 | |

| The Great Red Fox frightens Father Goat | 285 | |

| The Great Red Fox and Uncle Bear at the Store-house | 287 | |

| The Bear and the Fox go to Farmer John’s again | 289 | |

| ELEVEN O’CLOCK | 291 | |

| Head-piece—King Stork | 293 | |

| The Drummer helps the Old Man | 295 | |

| The Princess comes forth from the Castle at Night | 297 | |

| The Drummer helps himself | 299 | |

| The Drummer catches the One-eyed Raven | 303 | |

| TWELVE O’CLOCK | 305 | |

| Head-piece—The Best that Life has to Give | 307 | |

| The Blacksmith steals the Dwarf’s Pine-cones | 309 | |

| The Blacksmith chooses the Raven | 311 | |

| The Blacksmith brings the Little Bird to the Queen | 315 | |

| The Young Blacksmith Forges the Ring | 317 | |

I.

There was a king travelling through the country, and he and those with him were so far away from home that darkness caught them by the heels, and they had to stop at a stone mill for the night, because there was no other place handy.

While they sat at supper, they heard a sound in the next room, and it was a baby crying.

The miller stood in the corner, back of the stove, with his hat in his hand. “What is that noise?” said the king to him.

“Oh! it is nothing but another baby that the good storks have brought into the house to-day,” said the miller.

Now there was a wise man travelling along with the king, who could read the stars and everything that they told as easily as one can read one’s A B C’s in a book after one knows them, and the king, for a bit of a jest, would have him find out what the stars had to foretell of the miller’s baby. So the wise man went out and took a peep up in the sky, and by and by he came in again.

“Well,” said the king, “and what did the stars tell you?”

“The stars tell me,” said the wise man, “that you shall have a daughter, and that the miller’s baby, in the room yonder, shall marry her when they are old enough to think of such things.”

“What!” said the king, “and is a miller’s baby to marry the princess that is to come! We will see about that.” So the next day he took the miller aside and talked and bargained, and bargained and talked, until the upshot of the matter was that the miller was paid two hundred dollars, and the king rode off with the baby.

As soon as he came home to the castle he called his chief forester to him. “Here,” says he, “take this baby and do thus and so with it, and when you have killed it bring its heart to me, that I may know that you have really done as you have been told.”

So off marched the forester with the baby; but on his way he stopped at home, and there was his good wife working about the house.

“Well, Henry,” said she, “what do you do with the baby?”

“Oh!” said he, “I am just taking it off to the forest to do thus and so with it.”

“Come,” said she, “it would be a pity to harm the little innocent, and to have its blood on your hands. Yonder hangs the rabbit that you shot this morning, and its heart will please the king just as well as the other.”

Thus the wife talked, and the end of the business was that she and the man smeared a basket all over with pitch and set the baby adrift in it on the river, and the king was just as well satisfied with the rabbit’s heart as he would have been with the baby’s.

But the basket with the baby in it drifted on and on down the river, until it lodged at last among the high reeds that stood along the bank. By and by there came a great she-bear to the water to drink, and there she found it.

Now the huntsmen in the forest had robbed the she-bear of her cubs, so that her heart yearned over the little baby, and she carried it home with her to fill the place of her own young ones. There the baby throve until he grew to a great strong lad, and as he had fed upon nothing but bear’s milk for all that time, he was ten times stronger than the strongest man in the land.

One day, as he was walking through the forest, he came across a woodman chopping the trees into billets of wood, and that was the first time he had ever seen a body like himself. Back he went to the bear as fast as he could travel, and told her what he had seen. “That,” said the bear, “is the most wicked and most cruel of all the beasts.”

“Yes,” says the lad, “that may be so, all the same I love beasts like that as I love the food I eat, and I long for nothing so much as to go out into the wide world, where I may find others of the same kind.”

At this the bear saw very well how the geese flew, and that the lad would soon be flitting.

“See,” said she, “if you must go out into the wide world you must. But you will be wanting help before long; for the ways of the world are not peaceful and simple as they are here in the woods, and before you have lived there long you will have more needs than there are flies in summer. See, here is a little crooked horn, and when your wants grow many, just come to the forest and blow a blast on it, and I will not be too far away to help you.”

So off went the lad away from the forest, and all the coat he had upon his back was the skin of a bear dressed with the hair on it, and that was why folk called him “Bearskin.”

He trudged along the high-road, until he came to the king’s castle, and it was the same king who thought he had put Bearskin safe out of the way years and years ago.

Now, the king’s swineherd was in want of a lad, and as there was nothing better to do in that town, Bearskin took the place and went every morning to help drive the pigs into the forest, where they might eat the acorns and grow fat.

One day there was a mighty stir throughout the town; folk crying, and making a great hubbub. “What is it all about?” says Bearskin to the swineherd.

What! and did he not know what the trouble was? Where had he been for all of his life, that he had heard nothing of what was going on in the world? Had he never heard of the great fiery dragon with three heads that had threatened to lay waste all of that land, unless the pretty princess were given up to him? This was the very day that the dragon was to come for her, and she was to be sent up on the hill back of the town; that was why all the folk were crying and making such a stir.

“So!” says Bearskin, “and is there never a lad in the whole country that is man enough to face the beast? Then I will go myself if nobody better is to be found.” And off he went, though the swineherd laughed and laughed, and thought it all a bit of a jest. By and by Bearskin came to the forest, and there he blew a blast upon the little crooked horn that the bear had given him.

Presently came the bear through the bushes, so fast that the little twigs flew behind her. “And what is it that you want?” said she.

“I should like,” said Bearskin, “to have a horse, a suit of gold and silver armor that nothing can pierce, and a sword that shall cut through iron and steel; for I would like to go up on the hill to fight the dragon and free the pretty princess at the king’s town over yonder.”

“Very well,” said the bear, “look back of the tree yonder, and you will find just what you want.”

Yes; sure enough, there they were back of the tree: a grand white horse that champed his bit and pawed the ground till the gravel flew, and a suit of gold and silver armor such as a king might wear. Bearskin put on the armor and mounted the horse, and off he rode to the high hill back of the town.

By and by came the princess and the steward of the castle, for it was he that was to bring her to the dragon. But the steward stayed at the bottom of the hill, for he was afraid, and the princess had to climb it alone, though she could hardly see the road before her for the tears that fell from her eyes. But when she reached the top of the hill she found instead of the dragon a fine tall fellow dressed all in gold and silver armor. And it did not take Bearskin long to comfort the princess, I can tell you. “Come, come,” says he, “dry your eyes and cry no more; all the cakes in the oven are not burned yet; just go back of the bushes yonder, and leave it with me to talk the matter over with Master Dragon.”

The princess was glad enough to do that. Back of the bushes she went, and Bearskin waited for the dragon to come. He had not long to wait either; for presently it came flying through the air, so that the wind rattled under his wings.

Dear, dear! if one could but have been there to see that fight between Bearskin and the dragon, for it was well worth the seeing, and that you may believe. The dragon spit out flames and smoke like a house afire. But he could do no hurt to Bearskin, for the gold and silver armor sheltered him so well that not so much as one single hair of his head was singed. So Bearskin just rattled away the blows at the dragon—slish, slash, snip, clip—until all three heads were off, and there was an end of it.

After that he cut out the tongues from the three heads of the dragon, and tied them up in his pocket-handkerchief.

Then the princess came out from behind the bushes where she had lain hidden, and begged Bearskin to go back with her to the king’s castle, for the king had said that if any one killed the dragon he should have her for his wife. But no; Bearskin would not go to the castle just now, for the time was not yet ripe; but, if the princess would give them to him, he would like to have the ring from her finger, the kerchief from her bosom, and the necklace of golden beads from her neck.

The princess gave him what he asked for, and a sweet kiss into the bargain, and then Bearskin mounted upon his grand white horse and rode away to the forest. “Here are your horse and armor,” said he to the bear, “and they have done good service to-day, I can tell you.” Then he tramped back again to the king’s castle with the old bear’s skin over his shoulders.

“Well,” says the swineherd, “and did you kill the dragon?”

“Oh, yes,” says Bearskin, “I did that, but it was no such great thing to do after all.”

At that, the swineherd laughed and laughed, for he did not believe a word of it.

And now listen to what happened to the princess after Bearskin had left her. The steward came sneaking up to see how matters had turned out, and there he found her safe and sound, and the dragon dead. “Whoever did this left his luck behind him,” said he, and he drew his sword and told the princess that he would kill her if she did not swear to say nothing of what had happened. Then he gathered up the dragon’s three heads, and he and the princess went back to the castle again.

“There!” said he, when they had come before the king, and he flung down the three heads upon the floor, “I have killed the dragon and I have brought back the princess, and now if anything is to be had for the labor I would like to have it.” As for the princess, she wept and wept, but she could say nothing, and so it was fixed that she was to marry the steward, for that was what the king had promised.

At last came the wedding-day, and the smoke went up from the chimneys in clouds, for there was to be a grand wedding-feast, and there was no end of good things cooking for those who were to come.

“See now,” says Bearskin to the swineherd where they were feeding their pigs together, out in the woods, “as I killed the dragon over yonder, I ought at least to have some of the good things from the king’s kitchen; you shall go and ask for some of the fine white bread and meat, such as the king and princess are to eat to-day.”

Dear, dear, but you should have seen how the swineherd stared at this and how he laughed, for he thought the other must have gone out of his wits; but as for going to the castle—no, he would not go a step, and that was the long and the short of it.

“So! well, we will see about that,” says Bearskin, and he stepped to a thicket and cut a good stout stick, and without another word caught the swineherd by the collar, and began dusting his jacket for him until it smoked again.

“Stop, stop!” bawled the swineherd.

“Very well,” says Bearskin; “and now will you go over to the castle for me, and ask for some of the same bread and meat that the king and princess are to have for their dinner?”

Yes, yes; the swineherd would do anything that Bearskin wanted him.

“So! good,” says Bearskin; “then just take this ring and see that the princess gets it; and say that the lad who sent it would like to have some of the bread and meat that she is to have for her dinner.”

So the swineherd took the ring, and off he started to do as he had been told. Rap! tap! tap! he knocked at the door. Well, and what did he want?

Oh! there was a lad over in the woods yonder who had sent him to ask for some of the same bread and meat that the king and princess were to have for their dinner, and he had brought this ring to the princess as a token.

But how the princess opened her eyes when she saw the ring which she had given to Bearskin up on the hill! For she saw, as plain as the nose on her face, that he who had saved her from the dragon was not so far away as she had thought. Down she went into the kitchen herself to see that the very best bread and meat were sent, and the swineherd marched off with a great basket full.

“Yes,” says Bearskin, “that is very well so far, but I am for having some of the red and white wine that they are to drink. Just take this kerchief over to the castle yonder, and let the princess know that the lad to whom she gave it upon the hill back of the town would like to have a taste of the wine that she and the king are to have at the feast to-day.”

Well, the swineherd was for saying “no” to this as he had to the other, but Bearskin just reached his hand over toward the stout stick that he had used before, and the other started off as though the ground was hot under his feet. And what was the swineherd wanting this time—that was what they said over at the castle.

“The lad with the pigs in the woods yonder,” says the swineherd, “must have gone crazy, for he has sent this kerchief to the princess and says that he should like to have a bottle or two of the wine that she and the king are to drink to-day.”

When the princess saw her kerchief again, her heart leaped for joy. She made no two words about the wine, but went down into the cellar and brought it up with her own hands, and the swineherd marched off with it tucked under his coat.

“Yes, that was all very well,” said Bearskin, “I am satisfied so far as the wine is concerned, but now I would like to have some of the sweetmeats that they are to eat at the castle to-day. See, here is a necklace of golden beads; just take it to the princess and ask for some of those sweetmeats, for I will have them,” and this time he had only to look towards the stick, and the other started off as fast as he could travel.

The swineherd had no more trouble with this asking than with the others, for the princess went down-stairs and brought the sweetmeats from the pantry with her own hands, and the swineherd carried them to Bearskin where he sat out in the woods with the pigs.

Then Bearskin spread out the good things, and he and the swineherd sat down to the feast together, and a fine one it was, I can tell you.

“And now,” says Bearskin, when they had eaten all that they could, “it is time for me to leave you, for I must go and marry the princess.” So off he started, and the swineherd did nothing but stand and gape after him, with his mouth open, as though he were set to catch flies. But Bearskin went straight to the woods, and there he blew upon his horn, and the bear was with him as quickly this time as the last.

“Well, what do you want now,” said she.

“This time,” said Bearskin, “I want a fine suit of clothes made of gold and silver cloth, and a horse to ride on up to the king’s house, for I am going to marry the princess.”

Very well; there was what he wanted back of the tree yonder; and it was a suit of clothes fit for a great king to wear, and a splendid dapple-gray horse with a golden saddle and bridle studded all over with precious stones. So Bearskin put on the clothes and rode away, and a fine sight he was to see, I can tell you.

And how the folks stared when he rode up to the king’s castle. Out came the king along with the rest, for he thought that Bearskin was some great lord. But the princess knew him the moment she set eyes upon him, for she was not likely to forget him so soon as all that.

The king brought Bearskin into where they were feasting, and had a place set for him alongside of himself.

The steward was there along with the rest. “See,” said Bearskin to him, “I have a question to put. One killed a dragon and saved a princess, but another came and swore falsely that he did it. Now, what should be done to such a one?”

“Why this,” said the steward, speaking up as bold as brass, for he thought to face the matter down, “he should be put in a cask stuck all round with nails, and dragged behind three wild horses.”

“Very well,” said Bearskin, “you have spoken for yourself. For I killed the dragon up on the hill behind the town, and you stole the glory of the doing.”

“That is not so,” said the steward, “for it was I who brought home the three heads of the dragon in my own hand, and how can that be with the rest?”

Then Bearskin stepped to the wall, where hung the three heads of the dragon. He opened the mouth of each. “And where are the tongues?” said he.

At this the steward grew as pale as death, nevertheless he still spoke up as boldly as ever: “Dragons have no tongues,” said he. But Bearskin only laughed; he untied his handkerchief before them all, and there were the three tongues. He put one in each mouth, and they fitted exactly, and after that no one could doubt that he was the hero who had really killed the dragon. So when the wedding came it was Bearskin, and not the steward, who married the princess; what was done to him you may guess for yourselves.

And so they had a grand wedding, but in the very midst of the feast one came running in and said there was a great brown bear without, who would come in, willy-nilly. Yes, and you have guessed it right, it was the great she-bear, and if nobody else was made much of at that wedding you can depend upon it that she was.

As for the king, he was satisfied that the princess had married a great hero. So she had, only he was the miller’s son after all, though the king knew no more of that than my grandfather’s little dog, and no more did anybody but the wise man for the matter of that, and he said nothing of it, for wise folk don’t tell all they know.

II.

Once upon a time there was an old king who had a faithful servant. There was nobody in the whole world like him, and this was why: around his wrist he wore an armlet that fitted as close as the skin. There were words on the golden band; on one side they said:

And on the other side they said:

At last the old king felt that his end was near, and he called the faithful servant to him and besought him to serve and aid the young king who was to come as he had served and aided the old king who was to go. The faithful servant promised that which was asked, and then the old king closed his eyes and folded his hands and went the way that those had travelled who had gone before him.

Well, one day a stranger came to that town from over the hills and far away. With him he brought a painted picture, but it was all covered with a curtain so that nobody could see what it was.

He drew aside the curtain and showed the picture to the young king, and it was a likeness of the most beautiful princess in the whole world; for her eyes were as black as a crow’s wing, her cheeks were as red as apples, and her skin as white as snow. Moreover, the picture was so natural that it seemed as though it had nothing to do but to open its lips and speak.

The young king just sat and looked and looked. “Oh me!” said he, “I will never rest content until I have such a one as that for my own.”

“Then listen!” said the stranger, “this is a likeness of the princess that lives over beyond the three rivers. A while ago she had a wise bird on which she doted, for it knew everything that happened in the world, so that it could tell the princess whatever she wanted to know. But now the bird is dead, and the princess does nothing but grieve for it day and night. She keeps the dead bird in a glass casket, and has promised to marry whoever will bring a cup of water from the Fountain of Life, so that the bird may be brought back to life again.” That was the story the stranger told, and then he jogged on the way he was going, and I, for one, do not know whither it led.

But the young king had no peace or comfort in life for thinking of the princess who lived over beyond the three rivers. At last he called the faithful servant to him. “And can you not,” said he, “get me a cup of the Water of Life?”

“I know not, but I will try,” said the faithful servant, for he bore in mind what he had promised to the old king.

So out he went into the wide world, to seek for what the young king wanted, though the way there is both rough and thorny. On he went and on, until his shoes were dusty, and his feet were sore, and after a while he came to the end of the earth, and there was nothing more over the hill. There he found a little tumbled-down hut, and within the hut sat an old, old woman with a distaff, spinning a lump of flax.

“Good-morning, mother,” said the faithful servant.

“Good-morning, son,” says the old woman, “and where are you travelling that you have come so far?”

“Oh!” says the faithful servant, “I am hunting for the Water of Life, and have come as far as this without finding a drop of it.”

“Hoity, toity,” says the old woman, “if that is what you are after, you have a long way to go yet. The fountain is in the country that lies east of the Sun and west of the Moon, and it is few that have gone there and come back again, I can tell you. Besides that there is a great dragon that keeps watch over the water, and you will have to get the better of him before you can touch a drop of it. All the same, if you have made up your mind to go you may stay here until my sons come home, and perhaps they can put you in the way of getting there, for I am the Mother of the Four Winds of Heaven, and it is few places that they have not seen.”

So the faithful servant came in and sat down by the fire to wait till the Winds came home.

The first that came was the East Wind; but he knew nothing of the Water of Life and the land that lay east of the Sun and west of the Moon; he had heard folks talk of them both now and then, but he had never seen them with his own eyes.

The next that came was the South Wind, but he knew no more of it than his brother, and neither did the West Wind for the matter of that.

Last of all came the North Wind, and dear, dear, what a hubbub he made outside of the door, stamping the dust off of his feet before he came into the house.

“And do you know where the Fountain of Life is, and the country that lies east of the Sun and west of the Moon?” said the old woman.

Oh, yes, the North Wind knew where it was. He had been there once upon a time, but it was a long, long distance away.

“So; good! then perhaps you will give this lad a lift over there to-morrow,” said the old woman.

At this the North Wind grumbled and shook his head; but at last he said “yes,” for he is a good-hearted fellow at bottom, is the North Wind, though his ways are a trifle rough perhaps.

So the next morning he took the faithful servant on his back, and away he flew till the man’s hair whistled behind him. On they went and on they went and on they went, until at last they came to the country that lay east of the Sun and west of the Moon; and they were none too soon getting there either, I can tell you, for when the North Wind tumbled the faithful servant off his back he was so weak that he could not have lifted a feather.

“Thank you,” said the faithful servant, and then he was for starting away to find what he came for.

“Stop a bit,” says the North Wind, “you will be wanting to come away again after a while. I cannot wait here, for I have other business to look after. But here is a feather; when you want me, cast it into the air, and I will not be long in coming.”

Then away he bustled, for he had caught his breath again, and time was none too long for him.

The faithful servant walked along a great distance until, by and by, he came to a field covered all over with sharp rocks and white bones, for he was not the first by many who had been that way for a cup of the Water of Life.

There lay the great fiery dragon in the sun, sound asleep, and so the faithful servant had time to look about him. Not far away was a great deep trench like a drain in a swampy field; that was a path that the dragon had made by going to the river for a drink of water every day. The faithful servant dug a hole in the bottom of this trench, and there he hid himself as snugly as a cricket in the crack in the kitchen floor. By and by the dragon awoke and found that he was thirsty, and then started down to the river to get a drink. The faithful servant lay as still as a mouse until the dragon was just above where he was hidden; then he thrust his sword through its heart, and there it lay, after a turn or two, as dead as a stone.

After that he had only to fill the cup at the fountain, for there was nobody to say nay to him. Then he cast the feather into the air, and there was the North Wind, as fresh and as sound as ever. The North Wind took him upon its back, and away it flew until it came home again.

The faithful servant thanked them all around—the Four Winds and the old woman—and as they would take nothing else, he gave them a few drops of the Water of Life, and that is the reason that the Four Winds and their mother are as fresh and young now as they were when the world began.

Then the faithful servant set off home again, right foot foremost, and he was not as long in getting there as in coming.

As soon as the king saw the cup of the Water of Life he had the horses saddled, and off he and the faithful servant rode to find the princess who lived over beyond the three rivers. By and by they came to the town, and there was the princess mourning and grieving over her bird just as she had done from the first. But when she heard that the king had brought the Water of Life she welcomed him as though he were a flower in March.

They sprinkled a few drops upon the dead bird, and up it sprang as lively and as well as ever.

But now, before the princess would marry the king she must have a talk with the bird, and there came the hitch, for the Wise Bird knew as well as you and I that it was not the king who had brought the Water of Life. “Go and tell him,” said the Wise Bird, “that you are ready to marry him as soon as he saddles and bridles the Wild Black Horse in the forest over yonder, for if he is the hero who found the Water of Life he can do that and more easily enough.”

The princess did as the bird told her, and so the king missed getting what he wanted after all. But off he went to the faithful servant. “And can you not saddle and bridle the Wild Black Horse for me?” said he.

“I do not know,” said the faithful servant, “but I will try.”

So off he went to the forest to hunt up the Wild Black Horse, the saddle over his shoulder and the bridle over his arm. By and by came the Wild Black Horse galloping through the woods like a thunder gust in summer, so that the ground shook under his feet. But the faithful servant was ready for him; he caught him by the mane and forelock, and the Wild Black Horse had never had such a one to catch hold of him before.

But how they did stamp and wrestle: Up and down and here and there, until the fire flew from the stones under their feet. But the Wild Black Horse could not stand against the strength of ten men, such as the faithful servant had, so by and by he fell on his knees, and the faithful servant clapped the saddle on his back and slipped the bridle over his ears.

“Listen now,” says he; “to-morrow my master, the king, will ride you up to the princess’s house, and if you do not do just as I tell you, it will be the worse for you; when the king mounts upon your back you must stagger and groan, as though you carried a mountain.”

The horse promised to do as the other bade, and then the faithful servant jumped on his back and away to the king, who had been waiting at home for all this time.

The next day the king rode up to the princess’s castle, and the Wild Black Horse did just as the faithful servant told him to do; he staggered and groaned, so that everybody cried out, “Look at the great hero riding upon the Wild Black Horse!”

And when the princess saw him she also thought that he was a great hero. But the Wise Bird was of a different mind from her, for when the princess came to talk to him about marrying the king he shook his head. “No, no,” said he, “there is something wrong here, and the king has baked his cake in somebody else’s oven. He never saddled and bridled the Wild Black Horse by himself. Listen, you must say to him that you will marry nobody but the man who wears such and such a golden armlet with this and that written on it.”

So the princess told the king what the Wise Bird had bidden her to say, and the king went straightway to the faithful servant.

“You must let me have your armlet,” said he.

“Alas, master,” said the faithful servant, “that is a woful thing for me, for the one and only way to take the armlet off of my wrist is to cut my hand from off my body.”

“So!” says the king, “that is a great pity, but the princess will not have me without the armlet.”

“Then you shall have it,” says the faithful servant; but the king had to cut the hand off, for the faithful servant could not do it himself.

But, bless your heart! the armlet was ever so much too large for the king to wear! Nevertheless he tied it to his wrist with a bit of ribbon, and off he marched to the princess’s castle.

“Here is the armlet of gold,” said he, “and now will you marry me!”

But the Wise Bird sat on the princess’s chair. “Hut! tut!” says he, “it does not fit the man.”

Yes, that was so; everybody who was there could see it easily enough; and as for marrying him, the princess would marry nobody but the man who could wear the armlet.

What a hubbub there was then! Every one who was there was sure that the armlet would fit him if it fitted nobody else. But no; it was far too large for the best of them. The faithful servant was very sad, and stood back of the rest, over by the wall, with his arm tied up in a napkin. “You shall try it too,” says the princess; but the faithful servant only shook his head, for he could not try it on as the rest had done, because he had no hand. But the Wise Bird was there and knew what he was about; “See now,” says he, “maybe the Water of Life will cure one thing as well as another.”

Yes, that was true, and one was sent to fetch the cup. They sprinkled it on the faithful servant’s arm, and it was not twice they had to do it, for there was another hand as good and better than the old.

Then they gave him the armlet; he slipped it over his hand, and it fitted him like his own skin.

“This is the man for me,” says the princess, “and I will have none other;” for she could see with half an eye that he was the hero who had been doing all the wonderful things that had happened, because he said nothing about himself.

As for the king—why, all that was left for him to do was to pack off home again; and I, for one, am glad of it.

And this is true; the best packages are not always wrapped up in blue paper and tied with a gay string, and there are better men in the world than kings and princes, fine as they seem to be.

III.

There was a soldier marching along the road—left, right! left, right! He had been to the wars for five years, so that he was very brave, and now he was coming home again. In his knapsack were two farthings, and that was everything that he had in the world. All the same, he had a rich brother at home, and that was something to say.

So on he tramped until he had come to his rich brother’s house.

“Good-day, brother,” said he, “and how does the old world treat you.”

But the rich brother screwed up his face and rubbed his nose, for he was none too glad to see the other. “What!” said he, “and is the Pewter Penny back again?” That was the way that he welcomed the other to his house.

“Tut! tut!” says the brave soldier; “and is not this a pretty way to welcome a brother home to be sure! All that I want is just a crust of bread and a chance to rest the soles of my feet back of the stove a little while.”

Oh, well! if that was all that he wanted, he might have his supper and a bed for the night, but he must not ask for any more, and he must jog on in the morning and never come that way again.

Well, as no more broth was to be had from that dish, the soldier said that he would be satisfied with what he could get; so into the house he came.

Over by the fire was a bench, and on the bench was a basket, and in the basket were seven young ducks that waited where it was warm until the rest were hatched. The soldier saw nothing of these; down he sat, and the little young ducks said “peep!” and died all at once. Up jumped the soldier and over went the beer mug that sat by the fire so that the beer ran all around and put out the blaze.

At this the rich brother fell into a mighty rage. “See!” said he, “you never go anywhere but you bring Trouble with you. Out of the house before I make this broom rattle about your ears!”

And so the brave soldier had to go out under the blessed sky again. “Well! well!” said he, “the cream is all sour over yonder for sure and certain! All the same it will better nothing to be in the dumps, so we’ll just sing a bit of a song to keep our spirits up.” So the soldier began to sing, and by and by he heard that somebody was singing along with him.

“Halloa, comrade!” said he, “who is there?”

“Oh!” said a voice beside him, “it is only Trouble.”

“And what are you doing there, Trouble?” said the soldier.

Oh! Trouble was only jogging along with him. They had been friends and comrades for this many a bright day, for when had the soldier ever gone anywhere that Trouble had not gone along with him?

The brave soldier scratched his head. “Yes, yes,” says he; “that is all very fine; but there must be an end of the business. See! yonder is one road and here is another; you may go that road and I will go this, for I want no Trouble for a comrade.”

“Oh, no!” says Trouble, “I will never leave you now; you and I have been comrades too long for that!”

Very well! the soldier would see about that. They should go to the king, for things had come to a pretty pass if one could not choose one’s own comrades in this broad world, but must, willy-nilly, have Trouble always jogging at one’s heels.

So off they went—the soldier and Trouble—and by and by they came to the great town and there they found the king.

“Well, and what is the trouble now?” said the king.

Trouble indeed! Why, it was thus and so, here was that same Trouble tramping around at the soldier’s heels and would go wherever he went. Now, the soldier would like to know whether one had no right to choose one’s own comrades—that was the business that had brought him to the king!

Well, the king thought and thought and puzzled and puzzled, but that nut was too hard for him to crack, so he sent off for all of his wise councillors to see what they had to say about the matter.

So, when they had all come together the king told them that things were thus and so, and thus and so, and now he would like to know what they all thought about it.

Then the wise councillors began to talk and talk, and one said one thing and another another. After a while they fell to arguing with loud voices, and then they grew angry and began talking all at once, and last of all they came to fisticuffs. Then you should have heard what a racket they made! for they buffeted and cuffed one another until the hair flew as thick as dust in the mill.

That was the kind of prank that Trouble played them.

Now the king had a daughter, and the princess was as pretty a lass as one could find were he to hunt for seven summer days. When she heard all the hubbub she came to see what it was about, for that is the way with all of us, and of women folk more than any. And the king told her all about it; how the soldier had come to that town to get rid of Trouble, and how he had done nothing but bring it with him.

“Perhaps,” said she, “Trouble might leave him if he were married.”

At this the king fell into a mighty fume, for no man likes to have a woman tell him to do thus and so when things are in a pickle. He should like to know what the princess meant by coming and pouring her broth into their pot! If that was her notion she might help the soldier herself. Married he should be, and she should be his wife—that was what the king said.

So the soldier and the princess were married, and then the king had them both put into a great chest and thrown into the sea—but there was room in the chest for Trouble, and he went along with them.

Well, they floated on and on and on for a great long time, until, at last, the chest came ashore at a place where three giants lived.

The three giants were sitting on the shore fishing. “See, brothers,” said the first one of them, “yonder is a great chest washed up on the shore.” So they went over to where it was, and then the second giant took it on his shoulder and carried it home. After that they all three sat down to supper.

Just then the soldier’s nose began to itch and tickle, so that, for the life of him, he could not help sneezing.

“At-tchew!”—and there it was.

“Hark, brothers!” said the third giant, “yonder is somebody in the chest!”

So the three giants came and opened the chest, and there were the soldier and the princess. Trouble was there too, but the giants saw nothing of him.

They bound the soldier with strong cords so that they might have him to eat for breakfast in the morning.

And now what was to be done with the princess?

“See, brothers,” said the first giant, “I am thinking that a wife will about fit my needs. This lass will do as well as any, and, as I found her, I will just keep her.”

“Prut! how you talk!” said the second giant, “do you think that nobody is to marry in the wide world but you? Who was it brought the lass to the house I should like to know! No; I will marry her myself.”

“Stop!” said the third giant. “You are both going too fast on that road. I thought of a wife long before either of you. Who was it found that the lass was in the house, I should like to know!”

And so they talked and talked until they fell to quarrelling, and then to blows. Over they rolled, cuffing and slapping, until each one killed the other two, so that they all lay as dead as fishes. And that was an end of them.

“See, now,” said Trouble to the soldier, “who can say that I have done nothing for you? I tell you, comrade, that I am a good friend of yours, and love you as though you were my born brother. Listen! over yonder in the field is a great stone under which the giants have hidden stacks and stacks of money. Go and borrow a cart and two horses, and I will go with you and show you where it is.”

Well, you may guess that that was a song that pleased the soldier. Off he went and borrowed a cart and two horses. Then he and Trouble went into the field together, and Trouble showed him where the stone was where the treasure lay.

The soldier rolled the stone over, and there, sure enough, lay bags and bags, all full of gold and silver money.

Down he went into the pit and began bringing up the money and loading it into the cart. After a while he had brought it all but one bag full.

“See, Trouble,” said he, “my back is nearly broken with carrying the money. There is still one bag down there yet; go down like a good lad and bring it up for me.”

Oh, yes! Trouble would do that much for the soldier, for had they not been comrades for many and one bright, blessed days? Down he went into the pit, and then you may believe that the soldier was not long in rolling the stone into its place. So there was Trouble as tight as a fly in a bottle.

After that the soldier went back home again with great contentment—as I would have done had I ridden home upon a cart full of gold and silver, all of which belonged to me. He had left one bag of money, but then it was worth that much to be rid of Trouble.

After that the soldier built a ship and loaded it with the money. Then he and the princess sailed away to the king’s house, for they thought that maybe the king would like them better now that Trouble had left them and money had come.

When the king saw what a great boatload of gold and silver the soldier had brought home with him he was as pleased as pleased could be. He could not make enough of the brave soldier; he called him son, and walked about the streets with him arm in arm, so that the folks might see how fond he was of his son-in-law. Besides that he gave him half of the kingdom to rule over, so that the soldier and the princess lived together as snugly as a couple of mice in the barn when threshing is going on.

Well, one day a neighbor came to the rich brother and said, “Dear! dear! but the world is easy with your brother, the soldier!”

At this the rich brother pricked up his ears. “How is that?” said he—“my brother, the soldier? How comes the world to be easy with him, I should like to know?”

Oh, the neighbor could not tell him that; all that he knew was that the soldier was living over yonder with a princess for his wife, and more gold and silver money than a body could count in a week.

Well, well, this would never do! The rich brother must pick up acquaintance with the soldier again, now that he was rising in the world. So he put on his blue Sunday coat and his best hat, and away he went to the soldier’s house.

Well, the soldier was a good-natured fellow, and bore grudges against nobody, so he shook hands with his brother, and they sat down together by the stove. Then the rich brother wanted to know all about everything—how came it that the other was so well off in the world?

Oh, there was no secret about that; it happened thus and so. And then the soldier told all about it. After that the other went home, but there was a great buzzing in his head, I can tell you!

“Now,” says he to himself, “I will go over yonder to the giants’ house, and will let Trouble out from under the stone. Then he will come here to my brother and will turn things topsy-turvy, and I will get the bag of money that was left there.”

So, off he went until he came to the place where Trouble lay under the stone. He rolled the stone over, and—whisk! clip!—out popped Trouble from the hole. “And so you were leaving me here to be starved, were you?” said he.

“Oh, dear friend Trouble! it was not I, it was my brother, the soldier!”

Oh, well, that was all one to Trouble; now that he was out he would stay with the man who let him out, and there was an end of it. “So bring along the bag of gold,” says he, “for it is high time that we were going home.”

So the rich brother took the bag of gold over his shoulder, and the two went home together; and if anybody was down in the mouth, it was the rich brother.

And now everything went wrong with him, for Trouble dogged his heels wherever he went. At last his patience could hold out no longer, and he began to cudgel his brains to find some way to get rid of the other. So one day he says,

“Come, Trouble, we will go out into the forest this morning and cut some wood.”

Well, that suited Trouble as well as anything else, so off they went together, arm in arm. By and by they came to the forest, and there the man cut down a great tree. Then he split open the stump, and drove a wedge into it. So it came dinner-time, and then Trouble and he ate together.

“See now, Trouble,” said the man, “they tell me that you can go anywhere in all of the world.”

“Yes,” said Trouble, “that is so.”

“And could you go into that tree that I have split yonder?”

Oh, yes; Trouble could do that well enough.

If that was so the man would like to see him do it, that he would.

Oh, Trouble would do that and more, too, for a friend’s asking. So he made himself small and smaller, and so crept into the cleft in the log as easily as though he had been a mouse. But, no sooner was he snugly there than the man seized his axe and knocked out the wedge, and there was Trouble as safe as safe could be. He might beg and beg, but no, the man was deaf in that ear. He shouldered his axe and off he went, leaving Trouble where he was.

Dear me! that was a long time ago; or else some busybody must have let Trouble out of that log, for I know very well that he is stumping about the world nowadays.

IV.

There was a woman who owned a fine grey goose. “To-morrow,” said she, “I will pluck the goose for live feathers, so that I may take them to market and sell them for good hard money.”

This the goose heard, and liked it not. “Why should I grow live feathers for other folks to pluck?” said she to herself. So off she went into the wide world with nothing upon her back but what belonged to her.

By and by she came up with a sausage.

“Whither away, friend?” said the Grey Goose.

“Out into the wide world,” said the Sausage.

“Why do you travel that road?” said the Grey Goose.

“Why should I stay at home?” said the Sausage. “They stuff me with good meat and barley-meal over yonder, but they only do it for other folk’s feasting. That is the way with the world.”

“Yes, that is true,” said the Grey Goose; “and I too am going out into the world, for why should I grow live feathers for other folk’s plucking? So let us travel together, as we are both of a mind.”

Well, that suited the Sausage well enough, so off they went, arm in arm.

By and by they came up with a cock.

“Whither away, friend?” said the Grey Goose and the Sausage.

“Out into the wide world,” said the Cock.

“Why do you travel that road?” said the Grey Goose and the Sausage.

“Why should I stay at home?” said the Cock. “Every day they feed me with barley-corn, but it is only that I may split my throat in the mornings, calling the lads to the fields and the maids to the milking. That is the way with the world.”

“Yes, that is true,” said the Grey Goose; “why should I grow live feathers for other folk’s picking?”

And—

“Yes, that is true,” said the Sausage, “why should I be stuffed with meat and barley-meal for other folk’s feasting?”

So the three being all of a mind, they settled to travel the same road together.

Well, they went on and on and on, until, at last, they came to a deep forest, and, by and by, whom should they meet but a great red fox.

“Whither away, friends?” said he.

“Oh, we are going out into the wide world,” said the Grey Goose, the Sausage, and the Cock.

“And why do you travel that road?” said the Fox.

Oh, there was nothing but tangled yarn at home: the Grey Goose grew live feathers for other folk’s picking, the Sausage was stuffed for other folk’s feasting, and the Cock crowed in the morn for other folk’s waking. That was the way of the world over yonder, and so they had left it.

“Yes,” said the Fox, “that is true; so come with me into the deep forest, for there every one can live for himself! and nobody else.”

So they all went into the forest together, for the Fox’s words pleased them very much.

“And now,” said the Fox to the Grey Goose, “you shall be my wife,” for he had never had a sweetheart before, and even a Grey Goose is better than none.

“And what is to become of us?” said the Sausage and the Cock.

“You and I shall be dear friends,” said the Great Red Fox. Thereat the Cock and the Sausage were content, for it took but little to satisfy them.

Well, everything was just as the Great Red Fox had said it should be: the Goose kept her own feathers, the Sausage was stuffed for its own good, the Cock crowed for its own ears, and everything was as smooth as rich cream. Moreover, the Great Red Fox and the Grey Goose were husband and wife, and the Great Red Fox and the Sausage and the Cock were dear friends.

One morning says the Great Red Fox to the Grey Goose, “Neighbor Cock makes a mighty hubbub with his crowing!”

“Yes, that is so,” said the Grey Goose; for she always sang the same tune as the Great Red Fox, as a good wife should.

“Then,” said the Great Red Fox, “I will go over and have a talk with him.”

So off he packed, and by and by he came to Neighbor Cock’s house. Rap! tap! tap! he knocked at the door, and who should look out of the window but the Cock himself.

“See, Neighbor Cock,” said the Great Red Fox, “you make a mighty hubbub with that crowing of yours.”

“That may be so, and that may not be so,” said the Cock; “all the same, the hubbub is in my own house.”

“That is good,” said the Great Red Fox, “but one should not trouble one’s neighbors, even in one’s own house; so, if it suits you, we will have no more crowing.”

“I was made for crowing, and crow I must,” said the Cock.

“You must crow no more,” said the Great Red Fox.

“I must crow,” said the Cock.

“You must not crow,” said the Great Red Fox.

“I must crow,” said the Cock. And that was the last of it for—snip!—off went its head, and it crowed no more. Nevertheless, he had the last word, and that was some comfort. After that the Great Red Fox ate up the Cock, body and bones, and then he went home again.

“Will Neighbor Cock crow again?” said the Grey Goose.

“No; he will crow no more,” said the Fox; and that was true.

By and by came hungry times, with little or nothing in the house to eat. “Look!” said the Great Red Fox, “yonder is Neighbor Sausage, and he has plenty.”

“Yes, that is true,” said the Grey Goose.

“And one’s friend should help one when one is in need,” said the Great Red Fox.

“Yes, that is true,” said the Grey Goose again.

So off went the Great Red Fox to Neighbor Sausage’s house. Rap! tap! tap! he knocked at the door, and it was the Sausage himself who came.

“See,” said the Fox, “there are hungry times over at our house.”

“I am sorry for that,” said the Sausage; “but hungry times will come to the best of us.”

“That is so,” said the Great Red Fox, “but, all the same, you must help me through this crack. One would be in a bad pass without a friend to turn to.”

“But see,” said the Sausage, “all that I have is mine, and it is inside of me at that.”

“Nevertheless, I must have some of it,” said the Great Red Fox.

“But you can’t have it,” said the Sausage.

“But I must have it,” said the Great Red Fox.

“But you can’t have it,” said the Sausage.

And so they talked and talked and talked, but the end came at last, for one cannot talk forever to an empty stomach. Snip! snap! and the Sausage was down the Great Red Fox’s throat, and there was an end of it. And now the Fox had all that his friend had to give him, and so he went back home again.