The Fairy Ring

Kate Douglas Wiggin

The Fairy Ring

CHILDREN'S CRIMSON CLASSICS

EDITED BY KATE DOUGLAS WIGGIN

AND NORA ARCHIBALD SMITH

GOLDEN NUMBERS

A Book of Verse for Youth

THE POSY RING

A Book of Verse for Children

PINAFORE PALACE

A Book of Rhymes for Children

Library of Fairy Literature

THE FAIRY RING

MAGIC CASEMENTS

A Second Fairy Book

TALES OF LAUGHTER

A Third Fairy Book

TALES OF WONDER

A Fourth Fairy Book

THE TALKING BEASTS

Fables from Every Land

OTHER VOLUMES TO FOLLOW

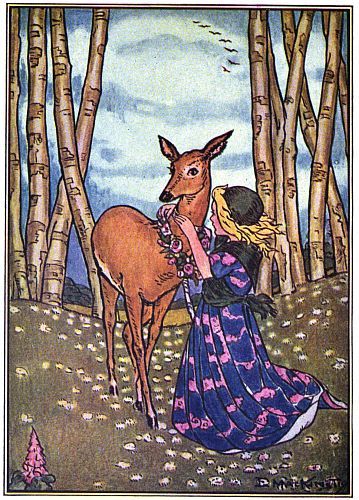

LITTLE BROTHER AND SISTER

LITTLE BROTHER AND SISTER

|

CRIMSON

CLASSICS |

|

THE FAIRY RING

KATE DOUGLAS WIGGIN and

NORA ARCHIBALD SMITH

——————————

ILLUSTRATED BY ELIZABETH MacKINSTRY

——————————

DOUBLEDAY, DORAN & COMPANY, INC.

GARDEN CITY 1934 NEW YORK

McCLURE, PHILLIPS & CO.

Copyright, 1910, by

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES

AT

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N. Y.

Messrs. McClure, Phillips & Company wish to make acknowledgment of their indebtedness to the following publishers:

Little, Brown & Company, for permission to use "Blanche and Vermilion" and "Prince Desire and Princess Mignonette" from Old-Fashioned Fairy Tales;

A. Wessells Company, for permission to use the story of "The Clever Prince" from Fairy Tales from Afar;

American Book Company, for permission to use "Drakesbill and His Friends" from Fairy Tales and Fables;

University Publishing Company, for permission to use "The Troll's Hammer" from Fairy Life;

Harper & Brothers, for permission to use "The Fair One with Golden Locks," "The White Cat," "Prince Cherry," and "The Frog Prince" from Miss Mulock's Fairy Book, and "Yvon and Finette," "The Twelve Months," and "The Story of Coquerico" from Laboulaye's Fairy Tales of all Nations;

G. P. Putnam's Sons, for permission to use "History of Tom Thumb" and "Tattercoats" from Joseph Jacobs's English Fairy Tales; "Munachar and Manachar" from Joseph Jacobs's Celtic Fairy Tales; and "Master Tobacco," "Mother Roundabout's Daughter," and "The Sheep and the Pig" from Dasent's Tales from the Field;

F. A. Stokes Company, for permission to use "Lars, My Lad," and "Twigmuntus and Cowbelliantus" from Fairy Tales from the Swedish;

Longmans, Green & Company, for permission to use the following stories: "The Yellow Dwarf," "The Many-Furred Creature," "Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle," "Princess and the Glass Hill," "The Golden Crab," "The Magic Ring," "Snow-white and Rose-red," "Graciosa and Percinet," "The Iron Stove," "The Good Little Mouse," and "The Three Feathers" from the Andrew Lang Fairy Books.

We also wish to express our thanks to Mr. Seumas MacManus, for permission to use "The Bee, the Harp, and the Bum-Clock," "The Long Leather Bag," and "The Widow's Daughter" from his books, Donegal Fairy Tales and In Chimney Corners, published by us.

CONTENTS

SCANDINAVIAN |

|

| PAGE | |

| East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon | 3 |

| The Golden Lantern, Golden Goat, and Golden Cloak | 13 |

| Mother Roundabout's Daughter | 21 |

| The Bear and Skrattel | 28 |

| The Golden Bird | 37 |

| The Doll in the Grass | 45 |

| The Princess on the Glass Hill | 47 |

| The Ram and the Pig who went into the Woods to Live by Themselves | 56 |

| The Troll's Hammer | 60 |

| The Clever Prince | 65 |

| "Lars, my Lad!" | 70 |

| Twigmuntus, Cowbelliantus, Perchnosius | 85 |

ENGLISH |

|

| Master Tobacco | 89 |

| The History of Tom Thumb | 95 |

| Tattercoats | 101 |

| History of Jack the Giant-Killer | 104 |

FRENCH |

|

| Yvon and Finette | 109 |

| The Fair One with Golden Locks | 138 |

| The Little Good Mouse | 148 |

| The Story of Blanche and Vermilion | 161 |

| Prince Desire and Princess Mignonetta | 165 |

| The Yellow Dwarf | 171 |

| Graciosa and Percinet | 179 |

| Drak, the Fairy | 197 |

| Drakesbill and His Friends | 202 |

| Riquet with the Tuft | 209 |

| The White Cat | 216 |

| Prince Cherry | 229 |

| The Twelve Months | 264 |

SPANISH |

|

| The Story of Coquerico | 254 |

| The Bird-Cage Maker | 259 |

GAELIC |

|

| The Bee, the Harp, the Mouse, and the Bum-Clock | 271 |

| The Long Leather Bag | 279 |

| The Widow's Daughter | 288 |

| Munachar and Manachar | 292 |

GERMAN |

|

| The Wild Swans | 238 |

| The Road to Fortune | 295 |

| The Golden Crab | 301 |

| The Table, the Ass, and the Stick | 307 |

| The Little Brother and Sister | 318 |

| The Old Griffin | 324 |

| The Three Feathers | 330 |

| The House in the Wood | 334 |

| Rapunzel | 339 |

| The Queen Bee | 343 |

| The Many-Furred Creature | 345 |

| Snow-white and Rose-red | 350 |

| The Frog Prince | 357 |

| The Goose Girl | 361 |

| Briar Rose | 367 |

| The Iron Stove | 370 |

| Rumpel-stilts-ken | 376 |

| Faithful John, the King's Servant | 379 |

| Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle | 386 |

RUSSIAN |

|

| The Magic Egg | 390 |

| The Sparrow and the Bush | 402 |

| The Iron Wolf | 404 |

EAST INDIAN |

|

| The Grateful Cobra | 408 |

| The Magic Ring | 413 |

| Tit for Tat | 426 |

| The Brahman, the Tiger, and the Six Judges | 427 |

| Muchie Lal | 431 |

| The Valiant Chatteemaker | 439 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| Little Brother and Sister | Frontispiece |

| FACING

PAGE |

|

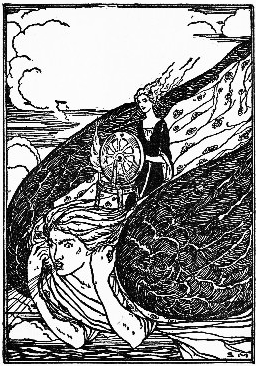

| The Lassie Riding Over the Sea on the Back of the North Wind | 10 |

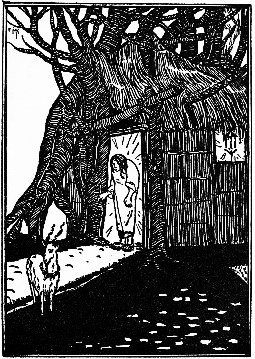

| The Troll's Hut, the Lantern, and the Goat with the Golden Horns | 14 |

| "She Said She Would Sit and Drive in a Silver Spoon" | 46 |

| Just as Cinderlad Turned His Horse Around, the Princess Threw the Golden Apple | 52 |

| "And When He Set Her Down He Gave Her a Kiss" | 90 |

| Tattercoats Forgot All Her Troubles and Fell to Dancing | 102 |

| "The Giant and the Conjurer now Knew that Their Wicked Course Was at an End" | 108 |

| "He Flung Huge Masses of Rock After the Vessel" | 122 |

| "She Wore Them Always . . . Loose and Flowing" | 138 |

| "I Feel as if I were the Daughter of some Great King" | 158 |

| "He Was a Week Trying to Tread on This Fatal Tail" | 166 |

| The Mermaid Taking the King of the Golden Mines to the Steel Castle | 178 |

| "Micheal, Petrified, Stood Mute, . . . Contemplating with a Frightened Air this Incongruous Dance" | 200 |

| "Eliza Went, and the King and the Archbishop Followed Her" | 252 |

| "March Rose in Turn, and Stirred the Fire with the Staff, when Behold! . . . It was Spring" | 266 |

| "An Ugly Old Woman with the Most Monstrous Nose Ever Beheld" | 292 |

| "In This Way the Fisherman Carried Him to the Castle" | 304 |

| "In the Middle of the Night, when Griffin was Snoring Away Lustily, Jack Reached Up and Pulled a Feather Out of His Tail" | 328 |

| "Then Dummling's Lovely Maiden Sprang Lightly and Gracefully Through the Ring" | 332 |

| ""What Are You Standing There Gaping for?" Screamed the Dwarf" | 356 |

| "Falada, Falada, There Thou Hangest!" | 364 |

| "At Last He Reached the Tower . . . Where Brier Rose Was Asleep" | 370 |

| "Just as It Had Come to the End of the Golden Thread It Reached the King's Son" | 388 |

| "The Ranee Said, 'This is a Dear Little Girl'" | 434 |

The elfin host come trooping by,

And hear the whir of fairy wings,

The goblin voices, shrill and high.

Behind them glides a magic train

Of Kings and Princes, armor-clad,

And serving as their squires bold

Boots, Ashiepattle, Cinderlad.

With silken rustle, flash of gem,

Queen and Czaritsa sweep along,

While red-capped Troll and rainbow Sprite

Peep out amid the enchanted throng.

Ting-ling, ting-ling, how sweet the ring,

Like golden bells, of fairy laughter;

Rap-tap, rap-tap, how sharp the clap

Of fairy footfalls following after!

Where witch-grass grows and fern-seed lies,

A Fairy Ring is dimly seen;

And there a glitt'ring host is met

To dance upon the moonlit green.

Riquet, the Tufted, lightly turns

The Fair One with the Golden Hair;

And Prince Desire and Mignonette

Form yet another graceful pair.

Tall as a tower stands Galifron;

The Desert Fay, with snakes bedight,

First pirouettes with him and then

With wee Tom Thumb, King Arthur's Knight.

Ting-ling, ting-ling, how sweet the ring,

Like golden bells, of fairy laughter;

Rap-tap, rap-tap, how sharp the clap

Of fairy footfalls following after!

Sweet, unseen harpers harp and sing,

Faint elfin horns the air repeat;

Rapunzel shakes her shining braids,

The White Cat trips with velvet feet.

Rose-red, Snow-white, the faithful Bear,

Cross hands with gallant Percinet;

While Tattercoats, in turn, salutes

Yvon, the Fearless, and Finette.

—But hark! the cock begins to crow;

The darkness turns to day, and, look!

The fairy dancers whirl within

The crimson covers of this book!

NORA ARCHIBALD SMITH

INTRODUCTION

"THERE was once upon a time a king who had a garden; in that garden was an apple tree, and on that apple tree grew a golden apple every year."

These stories are the golden apples that grew on the tree in the king's garden; grew and grew and grew as the golden years went by; and being apples of gold they could never wither nor shrink nor change, so that they are as beautiful and precious for you to pluck to-day as when first they ripened long, long ago.

Perhaps you do not care for the sort of golden apples that grew in the king's garden; perhaps you prefer plain russets or green pippins? Well, these are not to be despised, for they also are wholesome food for growing boys and girls; but unless you can taste the flavor and feel the magic that lies in the golden apples of the king's garden you will lose one of the joys of youth.

No one can help respecting apples (or stories) that gleam as brightly to-day as they did hundreds and thousands of years ago, when first the tiny blossoms ripened into precious fruit.

Whence these legends and traditions

With the odors of the forest,

With the dew and damp of meadows?"—

The so-called Household Tales, such as Drakesbill, The Little Good Mouse, and The Grateful Cobra go back to the times when men thought of animals as their friends and brothers, and in the fireside stories of that period the central figures were often wise and powerful beasts, beasts that had language, assumed human form, and protected as well as served mankind. Frogs, fishes, birds, wolves, cobras, cats, one and all win our sympathy, admiration, and respect as we read of their deeds of prowess, their sagacious counsel, their superhuman power of overcoming obstacles and rescuing from danger or death the golden-haired princess, the unhappy queen mother, or the intrepid but unfortunate prince.

The giants and ogres and witches in the fairy stories need not greatly affright even the youngest readers. For the most part they overreach themselves in ill-doing and are quite at the mercy (as they properly should be) of the brave and virtuous knight or the clever little princess.

If you chance to be an elder brother or sister it may surprise and distress you to find that all the grace, courage, wit, and beauty, as well as most of the good fortune, are vested in the youngest member of the household. The fairy-tale family has customs of its own when it comes to the distribution of vices and virtues, and the elder sons and daughters are likely to be haughty, selfish, and cruel, while the younger ones are as enchantingly beautiful as they are marvelously amiable. The malevolent stepmother still further complicates the domestic situation, and she is so wicked and malicious that if it were not for the dear and delightful one in your own household, or the equally lovable one next door, you might think stepmothers worse than ogres or witches. I cannot account for this prejudice, except that perhaps the ideal of mother love and mother goodness has always been so high in the world that the slightest deviation from it has been held up to scorn. As for the superhuman youngest son and daughter, perhaps they are used only to show us that the least and humblest things and persons are capable of becoming the mightiest and most powerful.

Wiseacres (and people who have no love for golden apples) say that in many of these tales "The greater the rogue the better his fortune"; but the Grimm brothers, most famous and most faithful of fairy-tale collectors, reply that the right user of these narratives "will find no evil therein, but, as an old proverb has it, merely a witness of his own heart. Children point at the stars without fear, while others, as the popular superstition goes, thereby offend the angels."

The moment you have plucked a golden apple from the magic tree in the king's garden (which phrase, being interpreted, means whenever you begin one of the tales in this book) you will say farewell to time and space as readily as if you had put on a wishing cap, or a pair of seven league boots, or had blown an elfin pipe to call the fairy host. It matters not when anything happened. It is "Once upon a time," or "A long time ago." As to just where, that is quite as uncertain and unimportant, for we all feel familiar with the fairy-tale landscape, which has delightful features all its own, and easily recognizable. The house is always in the heart of a deep, deep wood like the one "amidst the forest darkly green" where Snowwhite lived with the dwarfs. You know the Well at the World's End whence arose the Frog Prince; the Glass Mountain that Cinderlad climbed, first in his copper, then in his silver, then in his golden armor; the enchanted castle where the White Cat dwelt; the sea over which Faithful John sailed with the Princess of the Golden Roof.

In the story of The Spindle, the Shuttle, and the Needle, the prince has just galloped past the cottage in the wood where the maiden is turning her wheel, when the spindle leaps out of her hand to follow him on his way—leaps and dances and pursues him along the woodland path, the golden thread dragging behind. Then the prince turns (fairy princes always turn at the right time), sees the magic spindle, and, led by the shimmering thread, finds his way back to the lovely princess, the sweetest, loveliest, thriftiest, most bewitching little princess in the whole world, and a princess he might never have found had it not been for the kind offices of the spindle, shuttle, and needle.

This book is the magic spindle; the stories that were golden apples have melted into a golden thread, a train of bright images that will lead you into a radiant country where no one ever grows old; where, when the prince finds and loves the princess, he marries her and they are happy ever after; where the obstacles of life melt under the touch of comprehending kindness; where menacing clouds of misfortune are blown away by gay good will; and where wicked little trolls are invariably defeated by wise simpletons.

We feel that we can do anything when we journey in this enchanting country. Come, then, let us mount and be off; we can ride fast and far, for imagination is the gayest and fleetest of steeds. Let us climb the gilded linden tree and capture the Golden Bird. Let us plunge into the heart of the Briar Wood where the Rose o' the World lies sleeping. Let us break the spell that holds all her court in drowsy slumber, and then, coming out into the sunshine, mount and ride again into the forest. As we pass the Fairy Tree on the edge of the glade we will pluck a Merry Leaf, for this, when tucked away in belt or pouch, will give us a glad heart and a laughing eye all the day long. We shall meet ogres, no doubt, and the more the merrier, for, like Finette, we have but to cry "Abracadabra!" to defeat not ogres only, but wicked bailiffs, stewards, seneschals, witch hags, and even the impossibly vicious stepmother! Cormoran and Blunderbore will quail before us, for our magic weapons, like those of Cornish Jack, will be all-powerful. Then, flushed with triumph we will mount the back of the North Wind and search for the castle that lies East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon. Daylight will fade, the stars come out, the fire burn low on the hearth, playmates' voices sound unheeded. We shall still sit in the corner of the window seat with the red-covered volume on our knees; for hours ago the magic spindle wrought its spell, and we have been following the golden thread that leads from this work-a-day world into fairyland.

East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon

So one day—'twas on a Thursday evening, late at the fall of the year, the weather was so wild and rough outside, and it was so cruelly dark, and rain fell and wind blew till the walls of the cottage shook again—there they all sat round the fire, busy with this thing and that. But just then, all at once, something gave three taps on the windowpane. Then the father went out to see what was the matter, and when he got out of doors, what should he see but a great big white bear!

"Good evening to you," said the White Bear.

"The same to you," said the man.

"Will you give me your youngest daughter? If you will, I'll make you as rich as you are now poor," said the Bear.

Well, the man would not be at all sorry to be rich, but still he thought he must have a bit of a talk with his daughter first, so he went in and told them how there was a great white bear waiting outside, who had given his word to make them rich if he could only have the youngest daughter.

The lassie said "No" outright. Nothing could get her to say anything else. So the man went out and settled it with the White Bear that he should come again the next Thursday evening and get an answer.

Meantime, he talked his daughter over, and kept on telling her of all the riches they would get, and how well off she would be herself; and so at last she thought better of it, and washed and mended her rags, made herself as smart as she could, and was ready to start.

Next Thursday evening came the White Bear to fetch her, and she got upon his back with her bundle, and off they went.

So, when they had gone a bit of the way, the White Bear said:

"Are you afraid?"

No, she wasn't.

"Well, mind and hold tight to my shaggy coat, and then there's nothing to fear," said the White Bear.

So she rode a long, long way, until they came to a very steep hill. There, on the face of it, the White Bear gave a knock, and a door opened, and they came into a castle where there were many rooms, all lit up, rooms gleaming with silver and gold, and there, too, was a table ready laid, and it was all as grand as grand could be.

Then the White Bear gave her a silver bell, and when she wanted anything she had only to ring it and she would get it at once.

Well, after she had eaten and drunk, and evening wore on, she got sleepy after her journey, and thought she would like to go to bed. So she rang the bell, and she had scarce taken hold of it before she came into a chamber where there was a bed made, as fair and white as anyone could wish to sleep in, with silken pillows and curtains and gold fringe.

She slept quite soundly until morning; then she found her breakfast waiting in a pretty room. When she had eaten it, the girl made up her mind to take a walk around, in order to find out if there were any other people there besides herself.

But she saw nobody but an old woman, whom she took to be a witch, and as the dame beckoned to her, the girl went at once.

"Little girl," said the Witch, "if you'll promise not to say a word to anybody, I'll tell you the secret about this place."

Of course, the girl promised at once, so the old dame said:

"In this house there lives a White Bear, but you must know that he is only a White Bear in the daytime. Every night he throws off his beast shape and becomes a man, for he is under the spell of a wicked fairy. Now, be sure and not mention this to anybody, or misfortune will come," and with these words she disappeared.

So things went on happily for some time, but at last the girl began to grow sad and sorrowful, for she went about all day alone, and she longed to go home to see her father and mother and brothers and sisters.

"Well, well," said the Bear, "perhaps there's a cure for all this sorrow. But you must promise me one thing. When you go home, you mustn't talk about me, except when they are all present, or, if you do, you will bring bad luck to both of us."

So one Sunday the White Bear came and said now they would set off to see her father and mother.

Well, off they started, she sitting on his back, and they went far and long. At last they came to a grand house, and there her brothers and sisters were running about out of doors at play, and everything was so pretty 'twas a joy to see.

"This is where your father and mother live now," said the White Bear; "but don't forget what I told you, or you'll make us both unlucky."

No—bless her!—she'd not forget, and when they reached the house the White Bear turned right about and left her.

Then, when she went in to see her father and mother, there was such joy there was no end to it. None of them could thank her enough for all the good fortune she had brought them.

They had everything they wished, as fine as could be, and they all wanted to know how she got on and where she lived.

Well, she said it was very good to live where she did, and she had all she wished. What she said besides I don't know, but I don't believe any of them had the right end of the stick, or that they got much out of her.

But after dinner her sister called her outside the room, and asked all manner of questions about the White Bear—whether he was cross, and whether she ever set eyes on him, and such like—and the end of it all was that she told her sister the story of how the White Bear was under a spell.

But the other girl wouldn't listen to the story, for she said it couldn't be true, and this made the youngest daughter very angry.

In the evening the White Bear came and fetched her away, and when they had gone a bit of the way he asked her whether she had done as he had told her and refused to speak about him.

Then she confessed that she had spoken a few words to her sister about him, and the Bear was very angry, for he said she would surely bring bad luck to them both.

When they reached home, she remembered how her sister had refused to believe the story about the White Bear, so in the night, when she knew that the Bear was fast asleep, she stole out of bed, lighted her candle, and crept into his room. Yes, there he lay fast asleep, but instead of being a White Bear, he was the handsomest Prince you ever saw. She gave such a start that she dropped three spots of hot tallow from the candle on to his pillow, so she ran off in a great fright.

Next morning the White Bear said to her: "I fear you have found out my secret, for I saw the drops of tallow on my pillow this morning, and now I know that you spoke to your sister about me. If you had only kept quiet for a whole year, then I should have become a man for always, and I should have made you my wife at once. But now all ties are snapped between us, and I must go away to a big castle which stands East o' the sun and West o' the moon, and there, too, lives a Princess with a nose three ells long, and she's the wife I must have now."

The girl wept, and took it ill, but there was no help for it, go he must.

Then she asked if she mightn't go with him.

No! she mightn't.

"Tell me the way, then," she said, "and I'll search you out; that, surely, I may get leave to do."

Yes; she might do that, but there was no way to the place. It lay East o' the sun and West o' the moon, and thither she'd never find her way.

So next morning, when she woke, both Prince and castle were gone, and there she lay on a little green patch, in the midst of the thick, gloomy wood, and by her side lay the same bundle of rags that she had brought with her from her old home.

So when she had rubbed the sleep from her eyes, and wept till she was tired, she set out on her way and walked many, many days, till she came to a lofty crag. Under it sat an old hag, who played with a golden apple, which she tossed about. The lassie asked her if she knew the way to the Prince who lived in the castle that lay East o' the sun and West o' the moon, and who was to marry a Princess with a nose three ells long.

"How did you come to know about him?" said the old hag; "but maybe you are the lassie who ought to have had him?"

Yes, she was.

"So, so, it's you, is it?" said the old hag. "Well, all I know about him is that he lives in the castle that lies East o' the sun and West o' the moon, and thither you'll come, late or never; but still you may have the loan of my horse, and on him you can ride to my next neighbor. Maybe she'll be able to tell you what you want to know; and when you get there, just give the horse a switch under the left ear, and beg him to be off home; and stay, you may take this golden apple with you."

So she got upon the horse and rode a long, long time, till she came to another crag, under which sat another old hag, with a golden carding-comb in her hand. The lassie asked her if she knew the way to the castle that lay East o' the sun and West o' the moon, and she answered, like the first old hag, that she knew nothing about it, except that it was East o' the sun and West o' the moon.

"And thither you'll come, late or never; but you shall have the loan of my horse to go to my next neighbor; maybe she'll tell you all about it; and when you get there, just switch the horse under the left ear and beg him to be off home."

And this old hag gave her the golden carding-comb; it might be she'd find some use for it, she said. So the lassie got up on the horse and rode far, far away, and had a weary time; and so at last she came to another great crag, under which sat another old hag, spinning with a golden spinning wheel. The lassie asked her, too, if she knew the way to the Prince and where the castle was that lay East o' the sun and West o' the moon. So it was the same thing over again.

"Maybe it's you who ought to have had the Prince?" said the old hag.

Yes, it was.

But, she, too, didn't know the way a bit better than the other two. East o' the sun and West o' the moon she knew it was; that was all.

"And thither you'll come, late or never; but I'll lend you my horse, and then I think you'd best ride to the East Wind and ask him; maybe he knows those parts and can blow you thither. But when you get to him, you need only give the horse a switch under the left ear, and he'll trot home of himself."

And so, too, she gave the lassie the golden spinning wheel.

"Maybe you'll find a use for it," said the old hag.

Then on she rode a great many weary days before she got to the East Wind's house; but at last she did reach it, and then she asked the East Wind if he could tell her the way to the Prince who dwelt East o' the sun and West o' the moon. Yes, the East Wind had often heard about them, both the Prince and the castle, but he couldn't tell her the way, for he'd never blown so far.

"But, if you will, I'll go with you to my brother, the West Wind; maybe he's been there, for he's much stronger. So, if you will just jump on my back, I'll carry you thither."

Yes, she got on his back, and I should just think they went swiftly along.

So, when they reached there, they went into the West Wind's house, and the East Wind said the lassie he had brought was the one that ought to have married the Prince who lived in the castle East o' the sun and West o' the moon, and that she had set out to seek him. He then said how he had come with her, and would be glad to know if the West Wind knew how to get to the castle.

"Nay," said the West Wind, "for I've never blown so far; but, if you will, I'll go with you to our brother, the South Wind, for he's much stronger than either of us, and he has flapped his wings both far and wide. Maybe he'll tell you; so you can get on my back and I'll carry you to him."

Yes, she got on his back, and so they traveled to the South Wind, and they weren't so very long on the way, I should think.

When they reached there, the West Wind asked him if he could tell them the way to the castle that lay East o' the sun and West o' the moon, for this was the lassie who ought to have married the Prince who lived there.

"You don't say so! That's she, is it?" said the South Wind. "Well, I've blustered about in most places in my time, but so far I have never blown; but, if you will, I'll take you to my brother, the North Wind; he is the oldest and strongest of all of us. If he doesn't know where to find the place, you will never find anybody to tell you where it is. You can get on my back and I'll carry you thither."

Yes, she got on his back, and away he went from his house at a very high rate, and this time, too, she wasn't long on her way.

When they got to the North Wind's house, he was so wild and cross that the puffs came from quite a long way off.

"WHAT DO YOU WANT?" he roared out to them, in such a voice that it made them both shiver.

"Well," said the South Wind, "you needn't talk like that, for here I am, your brother, the South Wind, and here is the lassie who ought to have had the Prince who dwells at the castle that lies East o' the sun and West o' the moon, and now she wants to know if you were ever there, and can tell her the way, for she would be so glad to find it again."

THE LASSIE RIDING OVER THE SEA ON THE BACK OF THE NORTH WIND

THE LASSIE RIDING OVER THE SEA ON THE BACK OF THE NORTH WIND"YES! I KNOW WELL ENOUGH WHERE IT IS," said the North Wind. "Once in my life I blew an aspen leaf there, but I was so tired that I couldn't blow another puff for days after. But if you really wish to go there, and aren't afraid to trust yourself to me, I'll take you on my back and blow you thither."

Yes! with all her heart. She must and would get thither, if it were possible in any way; and as for fear, however madly he went, she wouldn't be at all afraid.

"Very well, then," said the North Wind. "But you must sleep here to-night, for we must have the whole day before us if we are to get thither at all."

Early next morning the North Wind woke her, and puffed himself up, and blew himself out, and made himself so stout and big 'twas fearful to look at him; so off they went, up through the air, as if they would never stop till they came to the world's end.

Down below there was such a storm, it threw down long tracts of wood and many houses, and when it swept over the great sea, ships foundered by hundreds.

So they tore on and on—nobody can believe how far they went—and all the while they still went over the sea, and the North Wind got more and more weary, and so out of breath he could scarce get out a puff. His wings drooped and drooped, till at last he sank so low that the crests of the waves dashed over his heels.

"Are you afraid?" asked the North Wind.

No, she wasn't.

But they weren't very far from land, and the North Wind had still so much strength in him that he managed to throw her upon the shore under the windows of the castle which lay East o' the sun and West o' the moon; but then he was so weak and worn out that he had to stay there and rest for many days before he was fit to return home.

Next morning the lassie sat down under the castle window and began to play with the golden apple; and the first person she saw was Long-nose, who was to marry the Prince.

"What do you want for your golden apple, lassie?" said Long-nose; and she threw up the window.

"It's not for sale, for gold or money," said the lassie.

"If it's not for sale for gold or money, what is it that you will sell it for?" said the Princess. "You may name your own price for it."

"Well, if you will let me speak a few words alone with the Prince who lives in the castle, I will give you the apple," she answered.

Yes, she might; that could be done. So the Princess got the golden apple, and the lassie was shown into the Prince's room. But when she got inside she found that the Prince was fast asleep, and although she shook him and called him loudly, it was no use, for she couldn't wake him, so she had to go away again.

Next day she sat down under the castle window again, and began to card with her golden carding-comb; and the same thing happened. The Princess asked what she wanted for it; and she said it wasn't for sale for either gold or money, but that if she might have a few words alone with the Prince, the Princess should have the comb.

So she was taken up to the Prince's room, and again she found him fast asleep; and although she wept and shook him for quite a long time she couldn't get life into him.

So the next morning the lassie sat down under the castle window and began to spin with her golden spinning wheel; and that, too, the Princess with the long nose wanted to have.

So she threw up the window and asked what the lassie wanted for it; and the girl said, as she had said twice before, that if she might have a few words alone with the Prince the Princess might have the wheel, and welcome.

Yes, she might do that; and the lassie was shown again into the Prince's room. This time he was wide awake, and he was very pleased indeed to see her.

"Ah!" said the Prince, "you've just come in the nick of time, for to-morrow is to be our wedding day; but now I won't have Long-nose, and you are the bride for me. I'll just say that I want to find out what my wife is fit for, and then I'll beg her to wash the pillow slip which has on it the three spots of tallow. She will be sure to say 'Yes'; but when she tries to get out the spots she'll soon find that it is not possible, for she is a troll, like all the rest of her family, and it is not possible for a troll to get rid of the marks. Then I'll say that I won't have any other bride than she who can wash out the spots of tallow, and I'll call you in to do it."

The wedding was to take place next day, so just before the ceremony the Prince said:

"First of all, I'd just like to see what my bride is fit for."

"Yes," said the mother, "I'm quite willing."

"Well, I have a pillow slip which, somehow or other, has got some spots of grease on it, and I have sworn never to take any bride but the woman who is able to wash them out for me. If she can't do that, she is not worth having."

Well, that was no great thing, they said, so they agreed; and she with the long nose began to wash away as hard as ever she could; but the more she rubbed and scrubbed the bigger the spots grew.

"Ah!" said the old hag, her mother, "you can't wash; let me try."

But she hadn't long taken the job in hand before it got far worse than ever; and with all her rubbing, wringing, and scrubbing, the spots grew bigger and blacker and darker and uglier.

Then all the other trolls began to wash; but the longer it lasted the blacker and uglier it grew, until at last it looked as though it had been up the chimney.

"Ah!" said the Prince, "you are none of you worth a straw; you can't wash. Why, there outside sits a beggar lassie, and I'll be bound she knows how to wash better than the whole lot of you."

So he shouted to the lassie to come in, and in she came.

"Can you wash this clean, lassie?" said he.

"I don't know, but I think I can."

And almost before she had taken it and dipped it in the water, it was white as driven snow, and whiter still.

"Yes, you are the lassie for me," said the Prince.

At that the old hag flew in such a rage that she burst on the spot, and the Princess with the long nose after her; and then the whole pack of trolls did the same.

As for the Prince and Princess, they had a grand wedding, and lived happily at the castle East o' the sun and West o' the moon until the end of their days.

The Golden Lantern, Golden Goat, and Golden Cloak

One day the old widow said to her sons: "You must all go abroad in the world, and seek your fortunes while you can. I am no longer able to feed you here at home, now that you are grown up." The lads answered that they wished for nothing better, since it was contrary to their mother's will that they should remain at home. They then prepared for their departure, and set out on their journey; but, after wandering about from place to place, were unable to procure any employment.

After journeying thus for a long time, they came, late one evening, to a vast lake. Far out in the water there was an island, on which there appeared a strong light, as of fire. The lads stopped on shore observing the wondrous light, and thence concluded that there must be human beings in the place. As it was now dark, and the brothers knew not where to find a shelter for the night, they resolved on taking a boat that lay among the reeds, and rowing over to the island to beg a lodging. With this view they placed themselves in the boat and rowed across. On approaching the island they perceived a little hut standing at the water's edge; on reaching which they discovered that the bright light that shone over the neighborhood proceeded from a golden lantern that stood at the door of the hut. In the yard without, a large goat was wandering about, with golden horns, to which small bells were fastened, that gave forth a pleasing sound whenever the animal moved. The brothers wondered much at all this, but most of all at the old crone, who with her daughter inhabited the hut. The crone was both old and ugly, but was sumptuously clad in a pelisse or cloak, worked so artificially with golden threads that it glittered like burnished gold in every hem. The lads saw now very clearly that they had come to no ordinary human being, but to a troll.

THE TROLL'S HUT, THE LANTERN, AND THE GOAT WITH THE GOLDEN HORNS

THE TROLL'S HUT, THE LANTERN, AND THE GOAT WITH THE GOLDEN HORNSAfter some deliberation the brothers entered, and saw the crone standing by the fireplace, and stirring with a ladle in a large pot that was boiling on the hearth. They told their story and prayed to be allowed to pass the night there; but the crone answered No! at the same time directing them to a royal palace, which lay on the other side of the lake. While speaking she kept looking intently on the youngest boy, as he was standing and casting his eyes over everything in the hut. The crone said to him: "What is thy name, my boy?" The lad answered smartly: "I am called Pinkel." The Troll then said: "Thy brothers can go their way, but thou shalt stay here; for thou appearest to me very crafty, and my mind tells me that I have no good to expect from thee if thou shouldst stay long at the King's palace." Pinkel now humbly begged to be allowed to accompany his brothers, and promised never to cause the crone harm or annoyance. At length he also had leave to depart; after which the brothers hastened to the boat, not a little glad that all three had escaped so well in this adventure.

Toward the morning they arrived at a royal palace, larger and more magnificent than anything they had ever seen before. They entered and begged for employment. The eldest two were received as helpers in the royal stables, and the youngest was taken as page to the King's young son; and, being a sprightly, intelligent lad, he soon won the good will of everyone, and rose from day to day in the King's favor. At this his brothers were sorely nettled, not enduring that he should be preferred to themselves. At length they consulted together how they might compass the fall of their young brother, in the belief that afterwards they should prosper better than before.

They therefore presented themselves one day before the King, and gave him an exaggerated account of the beautiful lantern that shed light over both land and water, adding that it ill beseemed a king to lack so precious a jewel. On hearing this the King's attention was excited, and he asked: "Where is this lantern to be found, and who can procure it for me?" The brothers answered: "No one can do that unless it be our brother Pinkel. He knows best where the lantern is to be found." The King was now filled with a desire to obtain the golden lantern about which he had heard tell, and commanded the youth to be called. When Pinkel came, the King said: "If thou canst procure me the golden lantern that shines over land and water I will make thee the chief man in my whole court." The youth promised to do his best to execute his lord's behest, and the King praised him for his willingness; but the brothers rejoiced at heart; for they well knew it was a perilous undertaking, which could hardly terminate favorably.

Pinkel now prepared a little boat, and, unaccompanied by anyone, rowed over to the island inhabited by the Troll-crone. When he arrived it was already evening, and the crone was busied in boiling porridge for supper, as was her custom. The youth creeping softly up to the roof cast from time to time a handful of salt through the chimney, so that it fell down into the pot that was boiling on the hearth. When the porridge was ready, and the crone had begun to eat, she could not conceive what had made it so salt and bitter. She was out of humor, and chided her daughter, thinking that she had put too much salt into the porridge; but let her dilute the porridge as she might, it could not be eaten, so salt and bitter was it. She then ordered her daughter to go to the well, that was just at the foot of the hill, and fetch water, in order to prepare fresh porridge. The maiden answered: "How can I go to the well? It is so dark out of doors that I cannot find the way over the hill." "Then take my gold lantern," said the crone, peevishly. The girl took the beautiful gold lantern accordingly, and hastened away to fetch the water. But as she stooped to lift the pail, Pinkel, who was on the watch, seized her by the feet, and cast her headlong into the water. He then took the golden lantern, and betook himself in all haste to his boat.

In the meantime the crone was wondering why her daughter stayed out so long, and, at the same moment, chancing to look through the window she saw the light gleaming far out on the water. At this sight she was sorely vexed, and hurrying down to the shore, cried aloud: "Is that thou, Pinkel?" The youth answered: "Yes, dear mother, it is I." The Troll continued: "Art thou not a great knave?" The lad answered: "Yes, dear mother, I am so." The crone now began to lament and complain, saying: "Ah! what a fool was I to let thee go from me; I might have been sure thou wouldst play me some trick. If thou ever comest hither again, thou shalt not escape." And so the matter rested for that time.

Pinkel now returned to the King's palace, and became the chief person at court, as the King had promised. But when the brothers were informed what complete success he had had in his adventure, they became yet more envious and embittered than before, and often consulted together how they might accomplish the fall of their young brother, and gain the King's favor for themselves.

Both brothers went, therefore, a second time before the King, and began relating at full length about the beautiful goat that had horns of the purest gold, from which little gold bells were suspended, which gave forth a pleasing sound whenever the animal moved. They added that it ill became so rich a king to lack so costly a treasure. On hearing their story, the King was greatly excited, and said: "Where is this goat to be found, and who can procure it for me?" The brothers answered: "That no one can do, unless it be our brother Pinkel; for he knows best where the goat is to be found." The King then felt a strong desire to possess the goat with the golden horns, and therefore commanded the youth to appear before him. When Pinkel came, the King said: "Thy brothers have been telling me of a beautiful goat with horns of the purest gold, and little bells fastened to the horns, which ring whenever the animal moves. Now it is my will that thou go and procure for me this goat. If thou art successful I will make thee lord over a third part of my kingdom." The youth having listened to this speech, promised to execute his lord's commission, if only fortune would befriend him. The King then praised his readiness, and the brothers were glad at heart, believing that Pinkel would not escape this time so well as the first.

Pinkel now made the necessary preparations and rowed to the island where the Troll-wife dwelt. When he reached it, evening was already advanced, and it was dark, so that no one could be aware of his coming, the golden lantern being no longer there, but shedding its light in the royal palace. The youth now deliberated with himself how to get the golden goat; but the task was no easy one; for the animal lay every night in the crone's hut. At length it occurred to his mind that there was one method which might probably prove successful, though, nevertheless, sufficiently difficult to carry into effect.

At night, when it was time for the crone and her daughter to go to bed, the girl went as usual to bolt the door. But Pinkel was just outside on the watch, and had placed a piece of wood behind the door, so that it would not shut close. The girl stood for a long time trying to lock it, but to no purpose. On perceiving this the crone thought there was something out of order, and called out that the door might very well remain unlocked for the night; as soon as it was daylight they could ascertain what was wanting. The girl then left the door ajar and laid herself down to sleep. When the night was a little more advanced, and the crone and her daughter were snug in deep repose, the youth stole softly into the hut, and approached the goat where he lay stretched out on the hearth. Pinkel now stuffed wool into all the golden bells, lest their sound might betray him; then seizing the goat, he bore it off to his boat. When he had reached the middle of the lake, he took the wool out of the goat's ears, and the animal moved so that the bells rang aloud. At the sound the crone awoke, ran down to the water, and cried in an angry tone: "Is that thou, Pinkel?" The youth answered: "Yes, dear mother, it is." The crone said: "Hast thou stolen my golden goat?" The youth answered: "Yes, dear mother, I have." The Troll continued: "Art thou not a big knave?" Pinkel returned for answer: "Yes, I am so, dear mother." Now the beldam began to whine and complain, saying: "Ah! what a simpleton was I for letting thee slip away from me. I well knew thou wouldst play me some trick. But if thou comest hither ever again, thou shalt never go hence."

Pinkel now returned to the King's court and obtained the government of a third part of the kingdom, as the King had promised. But when the brothers heard how the enterprise had succeeded, and also saw the beautiful lantern and the goat with golden horns, which were regarded by everyone as great wonders, they became still more hostile and embittered than ever. They could think of nothing but how they might accomplish his destruction.

They went, therefore, one day again before the king, to whom they gave a most elaborate description of the Troll-crone's fur cloak that shone like the brightest gold and was worked with golden threads in every seam. The brothers said it was more befitting a queen than a Troll to possess such a treasure, and added that that alone was wanting to the King's good fortune. When the King heard all this he became very thoughtful, and said: "Where is this cloak to be found, and who can procure it for me?" The brothers answered: "No one can do that except our brother Pinkel; for he knows best where the golden cloak is to be found." The King was thereupon seized with an ardent longing to possess the golden cloak, and commanded the youth to be called before him. When Pinkel came, the King said: "I have long been aware that thou hast an affection for my young daughter; and thy brothers have been telling me of a beautiful fur cloak which shines with the reddest gold in every seam. It is, therefore, my will that thou go and procure for me this cloak. If thou art successful, thou shalt be my son-in-law, and after me shalt inherit the kingdom." When the youth heard this he was glad beyond measure, and promised either to win the young maiden or perish in the attempt. The King thereupon praised his readiness; but the brothers were delighted in their false hearts, and trusted that the enterprise would prove their brother's destruction.

Pinkel then betook himself to his boat and crossed over to the island inhabited by the Troll-crone. On the way he anxiously deliberated with himself how he might get possession of the crone's golden cloak; but it appeared to him not very likely that his undertaking would prove successful, seeing that the Troll always wore the cloak upon her. So after having concerted divers plans, one more hazardous than another, it occurred to him that he would try one method which might perhaps succeed, although it was bold and rash.

In pursuance of his scheme he bound a bag under his clothes, and walked with trembling step and humble demeanor into the beldam's hut. On perceiving him, the Troll cast on him a savage glance, and said: "Pinkel, is that thou?" The youth answered: "Yes, dear mother, it is." The crone was overjoyed, and said: "Although thou art come voluntarily into my power, thou canst not surely hope to escape again from here, after having played me so many tricks." She then took a large knife and prepared to make an end of poor Pinkel; but the youth, seeing her design, appeared sorely terrified, and said: "If I must needs die, I think I might be allowed to choose the manner of my death. I would rather eat myself to death with milk porridge, than be killed with a knife." The crone thought to herself that the youth had made a bad choice, and therefore promised to comply with his wish. She then set a huge pot on the fire, in which she put a large quantity of porridge. When the mess was ready, she placed it before Pinkel that he might eat, who for every spoonful of porridge that he put into his mouth, poured two into the bag that was tied under his clothes. At length the crone began to wonder how Pinkel could contrive to swallow such a quantity; but just at the same moment the youth, making a show of being sick to death, sank down from his seat as if he were dead, and unobserved cut a hole in the bag, so that the porridge ran over the floor.

The crone, thinking that Pinkel had burst with the quantity of porridge he had eaten, was not a little glad, clapped her hands together, and ran off to look for her daughter, who was gone to the well. But as the weather was wet and stormy, she first took off her beautiful fur cloak and laid it aside in the hut. Before she could have proceeded far, the youth came to life again, and springing up like lightning seized on the golden cloak, and ran off at the top of his speed.

Shortly after, the crone perceived Pinkel as he was rowing in his little boat. On seeing him alive again, and observing the golden cloak glittering on the surface of the water, she was angry beyond all conception, and ran far out on the strand, crying: "Is that thou, Pinkel?" The youth answered: "Yes, it is I, dear mother." The crone said: "Hast thou taken my beautiful golden cloak?" Pinkel responded: "Yes, dear mother, I have." The Troll continued: "Art thou not a great knave?" The youth replied: "Yes, I am so, dear mother." The old witch was now almost beside herself, and began to whine and lament, and said: "Ah! how silly was it of me to let thee slip away. I was well assured thou wouldst play me many wicked tricks." They then parted from each other.

The Troll-wife now returned to her hut, and Pinkel crossed the water, and arrived safely at the King's palace; there he delivered the golden cloak, of which everyone said that a more sumptuous garment was never seen nor heard of. The King honorably kept his word with the youth, and gave him his young daughter to wife. Pinkel afterwards lived happy and content to the end of his days; but his brothers were and continued to be helpers in the stable as long as they lived.

Mother Roundabout's Daughter

At last the goody thought it too bad; so she told the lad that now he must begin to turn his hand to work and live steadily, or else there was nothing before both of them but starving to death. But that the lad had no mind to do. He said he would far rather woo Mother Roundabout's daughter; for if he could only get her, he would be able to live well and softly all his days, and sing and dance, and never do one stroke of work.

When his mother heard this she, too, thought it would be a very fine thing; and so she fitted out the lad as well as she could, that he might look tidy when he reached Mother Roundabout's house; and so he set off on his way.

Now when he got out of doors the sun shone warm and bright; but it had rained the night before, so that the ways were soft and miry and all the bog holes stood full of water. The lad took a short cut to Mother Roundabout's, and he sang and jumped, as was ever his wont; but just as he sprang and leaped he came to a bog hole, and over it lay a little bridge, and from the bridge he had to make a spring across a hole on to a tuft of grass, that he might not dirty his shoes. But plump, it went all at once, and just as he put his foot on the tuft it gave way under him, and there was no stopping till he found himself in a nasty, deep, dark hole. At first he could see nothing, but when he had been there a while he had a glimpse of a rat, that came wiggle-waggle up to him with a bunch of keys at the tip of her tail.

"What! you here, my boy?" said the rat. "Thank you kindly for coming to me. I have waited long for you. You come, of course, to woo me, and you are eager at it, I can very well see; but you must have patience yet a while, for I shall have a great dower. I am not ready for my wedding just yet, but I'll do my best that it shall be as soon as ever I can."

When she had said that, she brought out ever so many eggshells, with all sorts of bits and scraps, such as rats are wont to eat, and set them before him, and said:

"Now, you must sit down and eat; I am sure you must be both tired and hungry."

But the lad thought he had no liking for such food.

"If I were only well away from this, above ground again," he thought to himself, but he said nothing out loud.

"Now, I dare say you'd be glad to go home again," said the rat. "I know your heart is set on this wedding, and I'll make all the haste I can; and you must take with you this linen thread, and when you get up above you must not look round, but go straight home, and on the way you must mind and say nothing but

Short before, and long back';"

"Heaven be praised!" said the lad, when he got above ground. "Thither I'll never come again, if I can help it."

But he still had the thread in his hand, and he sprang and sang as he was wont; but even though he thought no more of the rat hole, he had got his tongue into the tune, and so he sang,

Short before, and long back."

So when he got back home into the porch he turned round, and there lay many, many hundred ells of the whitest linen, so fine that the handiest weaving girl could not have woven it finer.

"Mother! mother! come out," he cried and roared.

Out came the goody in a bustle, and asked whatever was the matter; but when she saw the linen woof, which stretched as far back as she could see and a bit besides, she couldn't believe her eyes, till the lad told her how it had all happened. And when she had heard it, and tried the woof between her fingers, she grew so glad that she, too, began to dance and sing.

So she took the linen and cut it out, and sewed shirts out of it both for herself and her son, and the rest she took into the town and sold, and got money for it. And now they both lived well and happily a while; but when the money was all gone, the goody had no more food in the house, and so she told her son he really must now begin to go to work, and live like the rest of the world, else there was nothing for it but starving for them both.

But the lad had more mind to go to Mother Roundabout and woo her daughter. Well, the goody thought that a very fine thing, for now he had good clothes on his back, and he was not such a bad-looking fellow either. So she made him smart, and fitted him out as well as she could; and he took out his new shoes and brushed them till they were as bright as glass, and when he had done that, off he went.

But all happened just as it did before. When he got out of doors the sun shone warm and bright; but it had rained overnight, so that it was soft and miry, and all the bog holes were full of water. The lad took the short cut to Mother Roundabout, and he sang and sprang as he was ever wont. Now he took another way than the one he went before; but just as he leaped and jumped, he got upon the bridge over the moor again, and from it he had to jump over a bog hole on to a turf that he might not soil his shoes. But plump it went, and down it went under him, and there was no stopping till he found himself in a nasty, deep, dark hole. At first he could see nothing; but when he had been there a while he caught a glimpse of a rat with a bunch of keys at the tip of her tail, who came wiggle-waggle up to him.

"What! you here, my boy?" said the rat. "That was nice of you to wish to see me so soon again. You are very eager, that I can see; but you really must wait a while, for there is still something wanting to my dower, though the next time you come, it shall be all right."

When she had said this she set before him all kinds of scraps and bits in eggshells, such as rats eat and like; but the lad thought it all looked like meat that had been already eaten once, and he wasn't hungry, he said; and all the time he thought, "If I could only once get above ground, well out of this hole." But he said nothing out loud.

So after a while the rat said:

"I dare say now you would be glad to get home again; but I'll hasten on the wedding as fast as ever I can. And now you must take with you this thread of wool; and when you come above ground you must not look round, but go straight home, and all the way you must mind and say nothing but

Short before, and long back';"

"Heaven be praised!" said the lad, "that I got away. Thither I'll never go again, if I can help it"; and so he sang and jumped as he was wont. As for the rat hole, he thought no more about it; but as he had got his tongue into tune he sang,

Short before, and long back";

When he had got into the yard at home again he turned and looked behind him, and there lay the finest cloth, more than many hundred ells; aye, almost above half a mile long, and so fine that no town dandy could have had finer cloth to his coat.

"Mother! mother! come out!" cried the lad.

So the goody came out of doors, and clapped her hands, and was almost ready to swoon for joy when she saw all that lovely cloth; and then he had to tell her how he had got it, and how it had all happened from first to last. Then they had a fine time of it, you may fancy. The lad got new clothes of the finest sort, and the goody went off to the town and sold the cloth by little and little, and made heaps of money. Then she decked out her cottage, and looked as smart in her old days as though she had been born a lady. So they lived well and happily; but at last that money came to an end too, and so the day came when the goody had no more food in the house, and then she told her son he really must turn his hand to work, and live like the rest of the world, else there was nothing but starvation staring both of them in the face.

But the lad thought it far better to go to Mother Roundabout and woo her daughter. This time the goody thought so too, and said not a word against it; for now he had new clothes of the finest kind, and he looked so well, she thought it quite out of the question that anyone could say "No" to so smart a lad. So she smartened him up, and made him as tidy as she could; and he himself brought out his new shoes, and rubbed them till they shone so he could see his face in them, and when he had done that, off he went.

This time he did not take the short cut, but made a great bend, for down to the rats he would not go if he could help it, he was so tired of all that wiggle-waggle and that everlasting bridal gossip. As for the weather and the ways, they were just as they had been twice before. The sun shone, so that it was dazzling on the pools and bog holes, and the lad sang and sprang as he was wont; but just as he sang and jumped, before he knew where he was, he was on the very same bridge across the bog again. So he tried to jump from the bridge over a bog hole on to a tuft that he might not dirty his bright shoes. Plump it went, and it gave way with him, and there was no stopping till he was down in the same nasty, deep, dark hole again. At first he was glad, for he could see nothing; but when he had been there a while he had a glimpse of the ugly rat, and loath he was to see her with the bunch of keys at the end of her tail.

"Good day, my boy!" said the rat; "you are heartily welcome again, for I see you can't bear to be any longer without me. Thank you, thank you kindly; but now everything is ready for the wedding, and we shall set off to church at once."

"Something dreadful is going to happen," thought the lad, but he said nothing out loud.

Then the rat whistled, and there came swarming out such a lot of small rats and mice of all the holes and crannies, and six big rats came harnessed to a frying pan; two mice got up behind as footmen, and two got up before and drove; some, too, got into the pan, and the rat with the bunch of keys at her tail took her seat among them. Then she said to the lad:

"The road is a little narrow here, so you must be good enough to walk by the side of the carriage, my darling boy, till it gets broader, and then you shall have leave to sit up in the carriage alongside of me."

"Very fine that will be, I dare say," thought the lad. "If I were only well above ground, I'd run away from the whole pack of you." That was what he thought, but he said nothing out loud.

So he followed them as well as he could; sometimes he had to creep on all fours, and sometimes he had to stoop and bend his back as well, for the road was low and narrow in places; but when it got broader he went on in front, and looked about him how he might best give them the slip and run away. But as he went forward he heard a clear, sweet voice behind him, which said:

"Now the road is good. Come, my dear, and get up into the carriage."

The lad turned round in a trice, and had near lost both nose and ears. There stood the grandest carriage, with six white horses to it, and in the carriage sat a maiden as bright and lovely as the sun, and round her sat others who were as pretty and soft as stars. They were a princess and her playfellows, who had been bewitched all together. But now they were free because he had come down to them, and never said a word against them.

"Come now," said the princess. So the lad stepped up into the carriage, and they drove to church; and when they drove from church again the princess said: "Now we will drive first to my house, and then we'll send to fetch your mother."

"That is all very well," thought the lad, for he still said nothing, even now; but, for all that, he thought it would be better to go home to his mother than down into that nasty rat hole. But just as he thought that, they came to a grand castle; into it they turned, and there they were to dwell. And so a grand carriage with six horses was sent to fetch the goody, and when it came back they set to work at the wedding feast. It lasted fourteen days, and maybe they are still at it. So let us all make haste; perhaps we, too, may come in time to drink the bridegroom's health and dance with the bride.

The Bear and Skrattel

So the King was well pleased, and ordered Gunter to set off at once with master Bruin: "Start with the morning's dawn," said he, "and make the best of your way."

The Norseman went home to his house in the forest; and early next morning he waked master Bruin, put the King's collar round his neck, and away they went over rocks and valleys, lakes and seas, the nearest road to the court of the King of Denmark. When they arrived there, the King was away on a journey, and Gunter and his fellow-traveler set out to follow. It was bright weather, the sun shone, and the birds sang, as they journeyed merrily on, day after day, over hill and over dale, till they came within a day's journey of where the King was.

All that afternoon they traveled through a gloomy, dark forest; but toward evening the wind began to whistle through the trees, and the clouds began to gather and threaten a stormy night. The road, too, was very rough, and it was not easy to tell which was more tired, Bruin or his master. What made the matter worse was that they had found no inn that day by the roadside, and their provisions had fallen short, so that they had no very pleasant prospect before them for the night. "A pretty affair this!" said Gunter. "I am likely to be charmingly off here in the woods, with an empty stomach, a damp bed, and a bear for my bedfellow."

While the Norseman was turning this over in his mind, the wind blew harder and harder, and the clouds grew darker and darker: the bear shook his ears, and his master looked at his wits' end, when to his great joy a woodman came whistling along out of the woods, by the side of his horse dragging a load of fagots. As soon as he came up Gunter stopped him, and begged hard for a night's lodging for himself and his countryman.

The woodman seemed hearty and good-natured enough, and was quite ready to find shelter for the huntsman; but as to the bear, he had never seen such a beast before in his life, and would have nothing to do with him on any terms. The huntsman begged hard for his friend, and told how he was bringing him as a present to the King of Denmark; and how he was the most good-natured, best-behaved animal in the world, though he must allow that he was by no means one of the handsomest.

The woodman, however, was not to be moved. His wife, he was sure, would not like such a guest, and who could say what he might take it into his head to do? Besides, he should lose his dog and his cat, his ducks and his geese; for they would all run away for fright, whether the bear was disposed to be friends with them or not.

"Good night, master huntsman!" said he; "if you and old shaggy-back there cannot part, I am afraid you must e'en stay where you are, though you will have a sad night of it, no doubt." Then he cracked his whip, whistled up his horse, and set off once more on his way homeward.

The huntsman grumbled, and Bruin grunted, as they followed slowly after; when to their great joy they saw the woodman, before he had gone many yards, pull up his horse once more and turn round. "Stay, stay!" said he; "I think I can tell you of a better plan than sleeping in a ditch. I know where you may find shelter, if you will run the risk of a little trouble from an unlucky imp that has taken up its abode in my old house down the hill yonder. You must know, friend, that till last winter I lived in yon snug little house that you will see at the foot of the hill if you come this way. Everything went smoothly on with us till one unlucky night, when the storm blew as it seems likely to do to-night, some spiteful guest took it into his head to pay us a visit; and there have ever since been such noises, clattering, and scampering up stairs and down, from midnight till the cock crows in the morning, that at last we were fairly driven out of house and home. What he is like no one knows; for we never saw him or anything belonging to him, except a little crooked high-heeled shoe, that he left one night in the pantry. But though we have not seen him, we know he has a hand or a paw as heavy as lead; for when it pleases him to lay it upon anyone, down he goes as if the blacksmith's hammer had hit him. There is no end of his monkey tricks. If the linen is hung out to dry, he cuts the line. If he wants a cup of ale, he leaves the tap running. If the fowls are shut up, he lets them loose. He puts the pig into the garden, rides upon the cows, and turns the horses into the hay yard; and several times he nearly burned the house down, by leaving a candle alight among the fagots. And then he is sometimes so nimble and active that when he is once in motion, nothing stands still around him, Dishes and plates—pots and pans—dance about, clattering, making the most horrible music, and breaking each other to pieces; and sometimes, when the whim takes him, the chairs and tables seem as if they were alive, and dancing a hornpipe, or playing battledore and shuttlecock together. Even the stones and beams of the house seem rattling against one another; and it is of no use putting things in order, for the first freak the imp took would turn everything upside down again.

"My wife and I bore such a lodger as long as we could, but at length we were fairly beaten; and as he seemed to have taken up his abode in the house, we thought it best to give up to him what he wanted; and the little rascal knew what we were about when we were moving, and seemed afraid we should not go soon enough. So he helped us off; for on the morning we were to start, as we were going to put our goods upon the wagon, there it stood before the door ready loaded; and when we started we heard a loud laugh, and a little sharp voice cried out of the window, 'Good-by, neighbors!' So now he has our old house all to himself to play his gambols in, whenever he likes to sleep within doors; and we have built ourselves a snug cottage on the other side of the hill, where we live as well as we can, though we have no great room to make merry in. Now if you, and your ugly friend there, like to run the hazard of taking up your quarters in the elf's house, pray do! Yonder is the road. He may not be at home to-night."

"We will try our luck," said Gunter. "Anything is better to my mind than sleeping out of doors such a night as this. Your troublesome neighbor will perhaps think so, too, and we may have to fight for our lodging; but never mind, Bruin is rather an awkward hand to quarrel with, and the goblin may perhaps find a worse welcome from him than your house dog could give him. He will at any rate let him know what a bear's hug is; for I dare say he has not been far enough north to know much about it yet."

Then the woodman gave Gunter a fagot to make his fire with, and wished him a good night. He and the bear soon found their way to the deserted house, and no one being at home they walked into the kitchen and made a capital fire.

"Lack-a-day!" said the Norseman; "I forgot one thing—I ought to have asked that good man for some supper; I have nothing left but some dry bread. However, this is better than sleeping in the woods. We must make the most of what we have, keep ourselves warm, and get to bed as soon as we can." So after eating up all their crusts, and drinking some water from the well close by, the huntsman wrapped himself up close in his cloak, and lay down in the snuggest corner he could find. Bruin rolled himself up in the corner of the wide fireplace, and both were fast asleep, the fire out, and everything quiet within doors long before midnight.

Just as the clock struck twelve the storm began to get louder—the wind blew—a slight noise within the room wakened the huntsman, and all on a sudden in popped a little ugly skrattel, scarce three spans high, with a hump on his back, a face like a dried pippin, a nose like a ripe mulberry, and an eye that had lost its neighbor. He had high-heeled shoes and a pointed red cap; and came dragging after him a nice fat kid, ready skinned and fit for roasting. "A rough night this," grumbled the goblin to himself; "but, thanks to that booby woodman, I've a house to myself. And now for a hot supper and a glass of good ale till the cock crows."

No sooner said than done. The skrattel busied himself about, here and there; presently the fire blazed up, the kid was put on the spit and turned merrily round. A keg of ale made its appearance from a closet, the cloth was laid, and the kid was soon dished up for eating. Then the little imp, in the joy of his heart, rubbed his hands, tossed up his red cap, danced before the hearth, and sang his song:

In the shivery midnight blast;

And 'tis dreary enough alone to bide,

Hungry and cold,

On the wintry wold,

Where the drifting snow falls fast.

"But 'tis cheery enough to revel by night,

In the crackling fagot's light;

'Tis merry enough to have and to hold

The savory roast,

And the nut-brown toast,

With jolly good ale and old."

The huntsman lay snug all this time, sometimes quaking, in dread of getting into trouble, and sometimes licking his lips at the savory supper before him, and half in the mind to fight for it with the imp. However, he kept himself quiet in his corner; till all of a sudden the little man's eye wandered from his cheering ale cup to Bruin's carcass, as he lay rolled up like a ball fast asleep in the chimney corner.

The imp turned round sharp in an instant, and crept softly nearer and nearer to where Bruin lay, looking at him very closely, and not able to make out what in the world he was. "One of the family, I suppose!" said he to himself. But just then Bruin gave his ears a shake, and showed a little of his shaggy muzzle. "Oh, ho!" said the imp, "that's all, is it? But what a large one! Where could he come from, and how came he here? What shall I do? Shall I let him alone or drive him out? Perhaps he may do me some mischief, and I am not afraid of mice or rats. So here goes! I have driven all the rest of the live stock out of the house, and why should I be afraid of sending this brute after them?"

With that the elf walked softly to the corner of the room, and taking up the spit, stole back on tiptoe till he got quite close to the bear; then raising up his weapon, down came a rattling thump across Bruin's mazard, that sounded as hollow as a drum. The bear raised himself slowly up, snorted, shook his head, then scratched it, opened first one eye, then the other, took a turn across the room, and grinned at his enemy; who, somewhat alarmed, ran back a few paces and stood with the spit in his hand, foreseeing a rough attack. And it soon came, for the bear, rearing himself up, walked leisurely forward, and putting out one of his paws caught hold of the spit, jerked it out of the goblin's hand, and sent it spinning to the other end of the kitchen.

And now began a fierce battle. This way and that way flew tables and chairs, pots and pans. The elf was one moment on the bear's back, lugging his ears and pommeling him with blows that might have felled an ox. In the next, the bear would throw him up in the air, and treat him as he came down with a hug that would make the little imp squall. Then up he would jump upon one of the beams out of Bruin's reach, and soon, watching his chance, would be down astride upon his back.

Meantime Gunter had become sadly frightened, and seeing the oven door open, crept in for shelter from the fray, and lay there quaking for fear. The struggle went on thus a long time, without its seeming at all clear who would get the better—biting, scratching, hugging, clawing, roaring, and growling, till the whole house rang. The elf, however, seemed to grow weaker and weaker. The rivals stood for a moment as if to get breath, and the bear was getting ready for a fierce attack when, all in a moment, the skrattel dashed his red cap right in his eye, and while Bruin was smarting with the blow and trying to recover his sight, darted to the door, and was out of sight in a moment, though the wind blew, the rain pattered, and the storm raged in a merciless manner.

"Well done! Bravo, Bruin!" cried the huntsman, as he crawled out of the oven and ran and bolted the door. "Thou hast combed his locks rarely; and as for thine own ears, they are rather the worse for pulling. But come, let us make the best of the good cheer our friend has left us!" So saying, they fell to and ate a hearty supper. The huntsman, wishing the skrattel a good night and pleasant dreams in a cup of his sparkling ale, laid himself down and slept till morning; and Bruin tried to do the same, as well as his aching bones would let him.

In the morning the huntsman made ready to set out on his way, and had not got far from the door before he met the woodman, who was eager to hear how he had passed the night. Then Gunter told him how he had been awakened, what sort of creature the elf was, and how he and Bruin had fought it out. "Let us hope," said he, "you will now be well rid of the gentleman. I suspect he will not come where he is likely to get any more of Bruin's hugs; and thus you will be well paid for your entertainment of us, which, to tell the truth, was none of the best, for if your ugly little tenant had not brought his supper with him, we should have had but empty stomachs this morning."

The huntsman and his fellow-traveler journeyed on, and let us hope they reached the King of Denmark safe and sound; but, to tell the truth, I know nothing more of that part of the story.

The woodman, meantime, went to his work, and did not fail to watch at night to see whether the skrattel came, or whether he was thoroughly frightened out of his old haunt by the bear, or whatever he might take the beast to be that had handled him as he never was handled before. But three nights passed over, and no traces being seen or heard of him, the woodman began to think of moving back to his old house.