The Road to Sinharat

Leigh Brackett

The people of Mars were perverse. They did

not want Earth's proffered gift of rich land, much

water, new power. They fought Rehabilitation.

And with them fought Carey, the Earthman, who

wanted only the secret that lay at the end of ...

THE ROAD TO SINHARAT

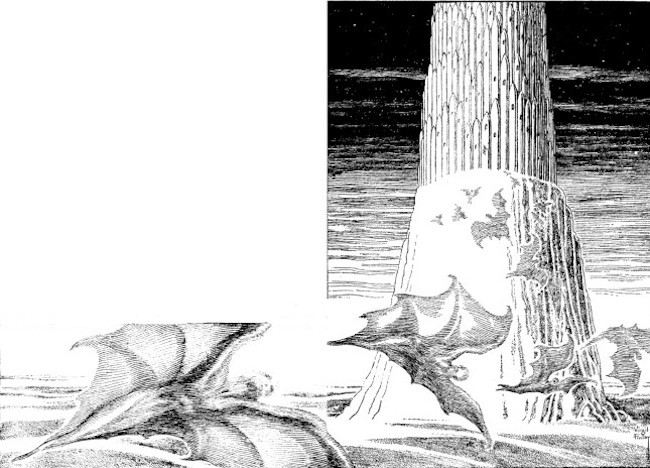

By LEIGH BRACKETT

Illustrated by FINLAY

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories May 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The door was low, deep-sunk into the thickness of the wall. Carey knocked and then he waited, stooped a bit under the lintel-stone, fitting his body to the meagre shadow as though he could really hide it there. A few yards away, beyond cracked and tilted paving-blocks, the Jekkara Low-Canal showed its still black water to the still black sky, and both were full of stars.

Nothing moved along the canal-site. The town was closed tight, and this in itself was so unnatural that it made Carey shiver. He had been here before and he knew how it ought to be. The chief industry of the Low-Canal towns is sinning of one sort or another, and they work at it right around the clock. One might have thought that all the people had gone away, but Carey knew they hadn't. He knew that he had not taken a single step unwatched. He had not really believed that they would let him come this far, and he wondered why they had not killed him. Perhaps they remembered him.

There was a sound on the other side of the door.

Carey said in the antique High Martian, "Here is one who claims the guest-right." In Low Martian, the vernacular that fitted more easily on his tongue, he said, "Let me in, Derech. You owe me blood."

The door opened narrowly and Carey slid through it, into lamp-light and relative warmth. Derech closed the door and barred it, saying,

"Damn you, Carey. I knew you were going to turn up here babbling about blood-debts. I swore I wouldn't let you in."

He was a Low-Canaller, lean and small and dark and predatory. He wore a red jewel in his left ear-lobe and a totally incongruous but comfortable suit of Terran synthetics, insulated against heat and cold. Carey smiled.

"Sixteen years ago," he said, "you'd have perished before you'd have worn that."

"Corruption. Nothing corrupts like comfort, unless it's kindness." Derech sighed. "I knew it was a mistake to let you save my neck that time. Sooner or later you'd claim payment. Well, now that I have let you in, you might as well sit down." He poured wine into a cup of alabaster worn thin as an eggshell and handed it to Carey. They drank, sombrely, in silence. The flickering lamp-light showed the shadows and the deep lines in Carey's face.

Derech said, "How long since you've slept?"

"I can sleep on the way," said Carey, and Derech looked at him with amber eyes as coldly speculative as a cat's.

Carey did not press him. The room was large, richly furnished with the bare, spare, faded richness of a world that had very little left to give in the way of luxury. Some of the things were fairly new, made in the traditional manner by Martian craftsmen. They were almost indistinguishable from the things that had been old when the Reed Kings and the Bee Kings were little boys along the Nile-bank.

"What will happen," Derech asked, "if they catch you?"

"Oh," said Carey, "they'll deport me first. Then the United Worlds Court will try me, and they can't do anything but find me guilty. They'll hand me over to Earth for punishment, and there will be further investigations and penalties and fines and I'll be a thoroughly broken man when they've finished, and sorry enough for it. Though I think they'll be sorrier in the long run."

"That won't help matters any," said Derech.

"No."

"Why," asked Derech, "why is it that they will not listen?"

"Because they know that they are right."

Derech said an evil word.

"But they do. I've sabotaged the Rehabilitation Project as much as I possibly could. I've rechanneled funds and misdirected orders so they're almost two years behind schedule. These are the things they'll try me for. But my real crime is that I have questioned Goodness and the works thereof. Murder they might forgive me, but not that."

He added wearily, "You'll have to decide quickly. The UW boys are working closely with the Council of City-States, and Jekkara is no longer untouchable. It's also the first place they'll look for me."

"I wondered if that had occurred to you." Derech frowned. "That doesn't bother me. What does bother me is that I know where you want to go. We tried it once, remember? We ran for our lives across that damned desert. Four solid days and nights." He shivered.

"Send me as far as Barrakesh. I can disappear there, join a southbound caravan. I intend to go alone."

"If you intend to kill yourself, why not do it here in comfort and among friends? Let me think," Derech said. "Let me count my years and my treasure and weigh them against a probable yard of sand."

Flames hissed softly around the coals in the brazier. Outside, the wind got up and started its ancient work, rubbing the house walls with tiny grains of dust, rounding off the corners, hollowing the window places. All over Mars the wind did this, to huts and palaces, to mountains and the small burrow-heaps of animals, laboring patiently toward a city when the whole face of the planet should be one smooth level sea of dust. Only lately new structures of metal and plastic had appeared beside some of the old stone cities. They resisted the wearing sand. They seemed prepared to stay forever. And Carey fancied that he could hear the old wind laughing as it went.

There was a scratching against the closed shutter in the back wall, followed by a rapid drumming of fingertips. Derech rose, his face suddenly alert. He rapped twice on the shutter to say that he understood and then turned to Carey. "Finish your wine."

He took the cup and went into another room with it. Carey stood up. Mingling with the sound of the wind outside, the gentle throb of motors became audible, low in the sky and very near.

Derech returned and gave Carey a shove toward an inner wall. Carey remembered the pivoted stone that was there, and the space behind it. He crawled through the opening. "Don't sneeze or thrash about," said Derech. "The stonework is loose, and they'd hear you."

He swung the stone shut. Carey huddled as comfortably as possible in the uneven hole, worn smooth with the hiding of illegal things for countless generations. Air and a few faint gleams of light seeped through between the stone blocks, which were set without mortar as in most Martian construction. He could even see a thin vertical segment of the room.

When the sharp knock came at the door, he discovered that he could hear quite clearly.

Derech moved across his field of vision. The door opened. A man's voice demanded entrance in the name of the United Worlds and the Council of Martian City-States.

"Please enter," said Derech.

Carey saw, more or less fragmentarily, four men. Three were Martians in the undistinguished cosmopolitan garb of the City-States. They were the equivalent of the FBI. The fourth was an Earthman, and Carey smiled to see the measure of his own importance. The spare, blond, good-looking man with the sunburn and the friendly blue eyes might have been an actor, a tennis-player, or a junior executive on holiday. He was Howard Wales, Earth's best man in Interpol.

Wales let the Martians do the talking, and while they did it he drifted unobtrusively about, peering through doorways, listening, touching, feeling. Carey became fascinated by him, in an unpleasant sort of way. Once he came and stood directly in front of Carey's crevice in the wall. Carey was afraid to breathe, and he had a dreadful notion that Wales would suddenly turn about and look straight in at him through the crack.

The senior Martian, a middle-aged man with an able look about him, was giving Derech a briefing on the penalties that awaited him if he harbored a fugitive or withheld information. Carey thought that he was being too heavy about it. Even five years ago he would not have dared to show his face in Jekkara. He could picture Derech listening amiably, lounging against something and playing with the jewel in his ear. Finally Derech got bored with it and said without heat,

"Because of our geographical position, we have been exposed to the New Culture." The capitals were his. "We have made adjustments to it. But this is still Jekkara and you're here on sufference, no more. Please don't forget it."

Wales spoke, deftly forestalling any comment from the City-Stater. "You've been Carey's friend for many years, haven't you?"

"We robbed tombs together in the old days."

"'Archeological research' is a nicer term, I should think."

"My very ancient and perfectly honorable guild never used it. But I'm an honest trader now, and Carey doesn't come here."

He might have added a qualifying "often," but he did not.

The City-Stater said derisively, "He has or will come here now."

"Why?" asked Derech.

"He needs help. Where else could he go for it?"

"Anywhere. He has many friends. And he knows Mars better than most Martians, probably a damn sight better than you do."

"But," said Wales quietly, "outside of the City-States all Earthmen are being hunted down like rabbits, if they're foolish enough to stay. For Carey's sake, if you know where he is, tell us. Otherwise he is almost certain to die."

"He's a grown man," Derech said. "He must carry his own load."

"He's carrying too much ..." Wales said, and then broke off. There was a sudden gabble of talk, both in the room and outside. Everybody moved toward the door, out of Carey's vision, except Derech who moved into it, relaxed and languid and infuriatingly self-assured. Carey could not hear the sound that had drawn the others but he judged that another flier was landing. In a few minutes Wales and the others came back, and now there were some new people with them. Carey squirmed and craned, getting closer to the crack, and he saw Alan Woodthorpe, his superior, Administrator of the Rehabilitation Project for Mars, and probably the most influential man on the planet. Carey knew that he must have rushed across a thousand miles of desert from his headquarters at Kahora, just to be here at this moment.

Carey was flattered and deeply moved.

Woodthorpe introduced himself to Derech. He was disarmingly simple and friendly in his approach, a man driven and wearied by many vital matters but never forgetting to be warm, gracious, and human. And the devil of it was that he was exactly what he appeared to be. That was what made dealing with him so impossibly difficult.

Derech said, smiling a little, "Don't stray away from your guards."

"Why is it?" Woodthorpe asked. "Why this hostility? If only your people would understand that we're trying to help them."

"They understand that perfectly," Derech said. "What they can't understand is why, when they have thanked you politely and explained that they neither need nor want your help, you still refuse to leave them alone."

"Because we know what we can do for them! They're destitute now. We can make them rich, in water, in arable land, in power—we can change their whole way of life. Primitive people are notoriously resistant to change, but in time they'll realize...."

"Primitive?" said Derech.

"Oh, not the Low-Canallers," said Woodthorpe quickly. "Your civilization was flourishing, I know, when Proconsul was still wondering whether or not to climb down out of his tree. For that very reason I cannot understand why you side with the Drylanders."

Derech said, "Mars is an old, cranky, dried-up world, but we understand her. We've made a bargain with her. We don't ask too much of her, and she gives us sufficient for our needs. We can depend on her. We do not want to be made dependent on other men."

"But this is a new age," said Woodthorpe. "Advanced technology makes anything possible. The old prejudices, the parochial viewpoints, are no longer...."

"You were saying something about primitives."

"I was thinking of the Dryland tribes. We had counted on Dr. Carey, because of his unique knowledge, to help them understand us. Instead, he seems bent on stirring them up to war. Our survey parties have been set upon with the most shocking violence. If Carey succeeds in reaching the Drylands there's no telling what he may do. Surely you don't want...."

"Primitive," Derech said, with a ring of cruel impatience in his voice. "Parochial. The gods send me a wicked man before a well-meaning fool. Mr. Woodthorpe, the Drylanders do not need Dr. Carey to stir them up to war. Neither do we. We do not want our wells and our water-courses rearranged. We do not want to be resettled. We do not want our population expanded. We do not want the resources that will last us for thousands of years yet, if they're not tampered with, pumped out and used up in a few centuries. We are in balance with our environment, we want to stay that way. And we will fight, Mr. Woodthorpe. You're not dealing with theories now. You're dealing with our lives. We are not going to place them in your hands."

He turned to Wales and the Martians. "Search the house. If you want to search the town, that's up to you. But I wouldn't be too long about any of it."

Looking pained and hurt, Woodthorpe stood for a moment and then went out, shaking his head. The Martians began to go through the house. Carey heard Derech's voice say, "Why don't you join them, Mr. Wales?"

Wales answered pleasantly, "I don't like wasting my time." He bade Derech good night and left, and Carey was thankful.

After a while the Martians left too. Derech bolted the door and sat down again to drink his interrupted glass of wine. He made no move to let Carey out, and Carey conquered a very strong desire to yell at him. He was getting just a touch claustrophobic now. Derech sipped his wine slowly, emptied the cup and filled it again. When it was half empty for the second time a girl came in from the back.

She wore the traditional dress of the Low-Canals, which Carey was glad to see because some of the women were changing it for the cosmopolitan and featureless styles that made all women look alike, and he thought the old style was charming. Her skirt was a length of heavy orange silk caught at the waist with a broad girdle. Above that she wore nothing but a necklace and her body was slim and graceful as a bending reed. Twisted around her ankles and braided in her dark hair were strings of tiny bells, so that she chimed as she walked with a faint elfin music, very sweet and wicked.