Bonnie Scotland and What We Owe Her

William Elliot Griffis

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

William E. Griffis, D.D.

BONNIE SCOTLAND AND WHAT WE OWE HER. Illustrated.

BELGIUM: THE LAND OF ART. Its History, Legends, Industry and Modern Expansion. Illustrated.

CHINA’S STORY, IN MYTH, LEGEND, ART AND ANNALS. Illustrated.

THE STORY OF NEW NETHERLAND. Illustrated.

YOUNG PEOPLE’S HISTORY OF HOLLAND. Illustrated.

BRAVE LITTLE HOLLAND, AND WHAT SHE TAUGHT US. Illustrated. In Riverside Library for Young People. In Riverside School Library. Half leather.

THE AMERICAN IN HOLLAND. Sentimental Ramblings in the Eleven Provinces of the Netherlands. With a map and illustrations.

THE PILGRIMS IN THEIR THREE HOMES,—ENGLAND, HOLLAND, AND AMERICA. Illustrated. In Riverside Library for Young People.

JAPAN: IN HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND ART. In Riverside Library for Young People.

MATTHEW CALBRAITH PERRY. A typical American Naval Officer. Illustrated.

TOWNSEND HARRIS, First American Envoy in Japan. With portrait.

THE LILY AMONG THORNS. A Study of the Biblical Drama entitled The Song of Songs. White cloth, gilt top.

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston and New York

BONNIE SCOTLAND

AND WHAT WE OWE HER

BONNIE SCOTLAND

AND WHAT WE OWE HER

BY

WILLIAM ELLIOT GRIFFIS

With Illustrations

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1916

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY WILLIAM ELLIOT GRIFFIS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published October, 1916

DEDICATED

TO THE THREE WOMEN FRIENDS

QUANDRIL

LYRA

FRANCES

FELLOW TRAVELLERS AND GUESTS IN THE

LAND OF COLUMBA, MARGARET, BRUCE, BURNS

AND SCOTT

PREFACE

In the period from student days until within the shadow of the great world-war of 1914, I made eight journeys to and in Scotland; five of them, more or less when alone, and three in company with wife or sister, thus gaining the manifold benefits of another pair of eyes. On foot, and in a variety of vehicles, in Highlands and Lowlands, over moor and water, salt and fresh, I went often and stayed long. Of all things remembered best and most delightfully in this land, so rich in the “voices of freedom,”—the mountains and the sea,—the first is the Scottish home so warm with generous hospitality.

In this book I have attempted to tell of the Scotsman at home and abroad, his part in the world’s work, and to picture “Old Scotia’s grandeur,” as illustrated in humanity, as well as in history, nature, and art, while showing in faint measure the debt which we Americans owe to Bonnie Scotland.

W. E. G.

Ithaca, New York.

CONTENTS

| I. | The Spell of the Invisible | 1 |

| II. | The Outpost Isles | 7 |

| III. | Glasgow: the Industrial Metropolis | 17 |

| IV. | Edinburgh the Picturesque | 27 |

| V. | Melrose Abbey and Sir Walter Scott | 38 |

| VI. | Rambles along the Border | 50 |

| VII. | The Lay of the Land: Dunfermline | 65 |

| VIII. | Dundee: the Gift of God | 76 |

| IX. | The Glamour of Macbeth | 88 |

| X. | Stirling: Castle, Town, and Towers | 97 |

| XI. | Oban and Glencoe—Chapters in History | 108 |

| XII. | Scotland’s Island World—Iona and Staffa | 119 |

| XIII. | The Caledonian Canal—Scottish Sports | 131 |

| XIV. | Inverness: the Capital of the Highlands | 143 |

| XV. | “Bonnie Prince Charlie” | 156 |

| XVI. | The Old Highlands and their Inhabitants | 164 |

| XVII. | Heather and Highland Costume | 177 |

| XVIII. | The Northeast Coast—Aberdeen and Elgin | 191 |

| XIX. | The Orkneys and the Shetlands | 202 |

| XX. | Loch Lomond and the Trossachs | 213 |

| XXI. | Robert Burns and his Teachers | 223 |

| XXII. | Kirk, School, and Freedom | 234 |

| XXIII. | John Knox: Scotland’s Mightiest Son | 247 |

| XXIV. | Invergowrie: In Scottish Homes | 259 |

| XXV. | America’s Debt to Scotland | 270 |

| Chronological Framework of Scotland’s History | 279 | |

| Index | 287 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

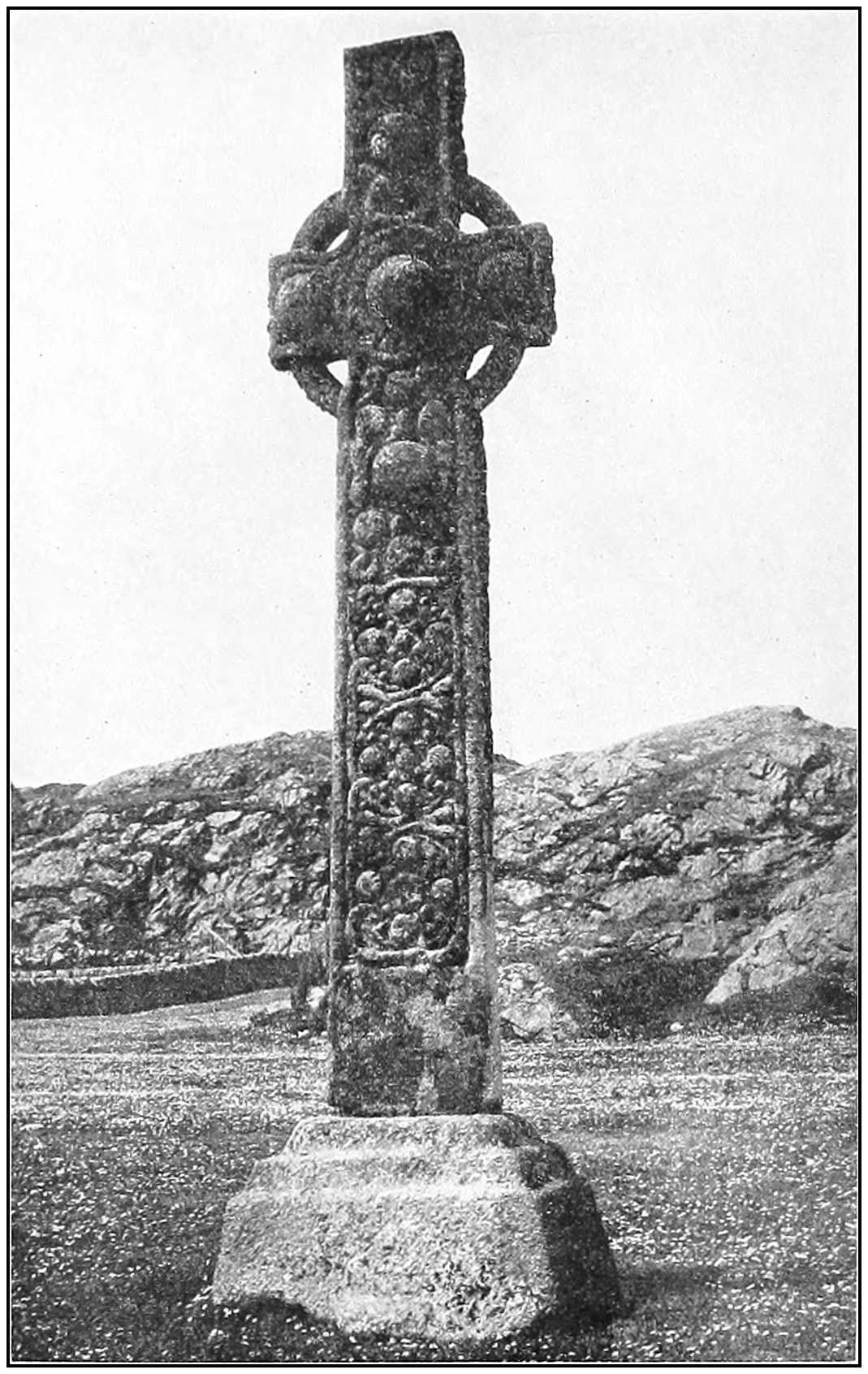

| St. Martin’s Cross at Iona Frontispiece | |

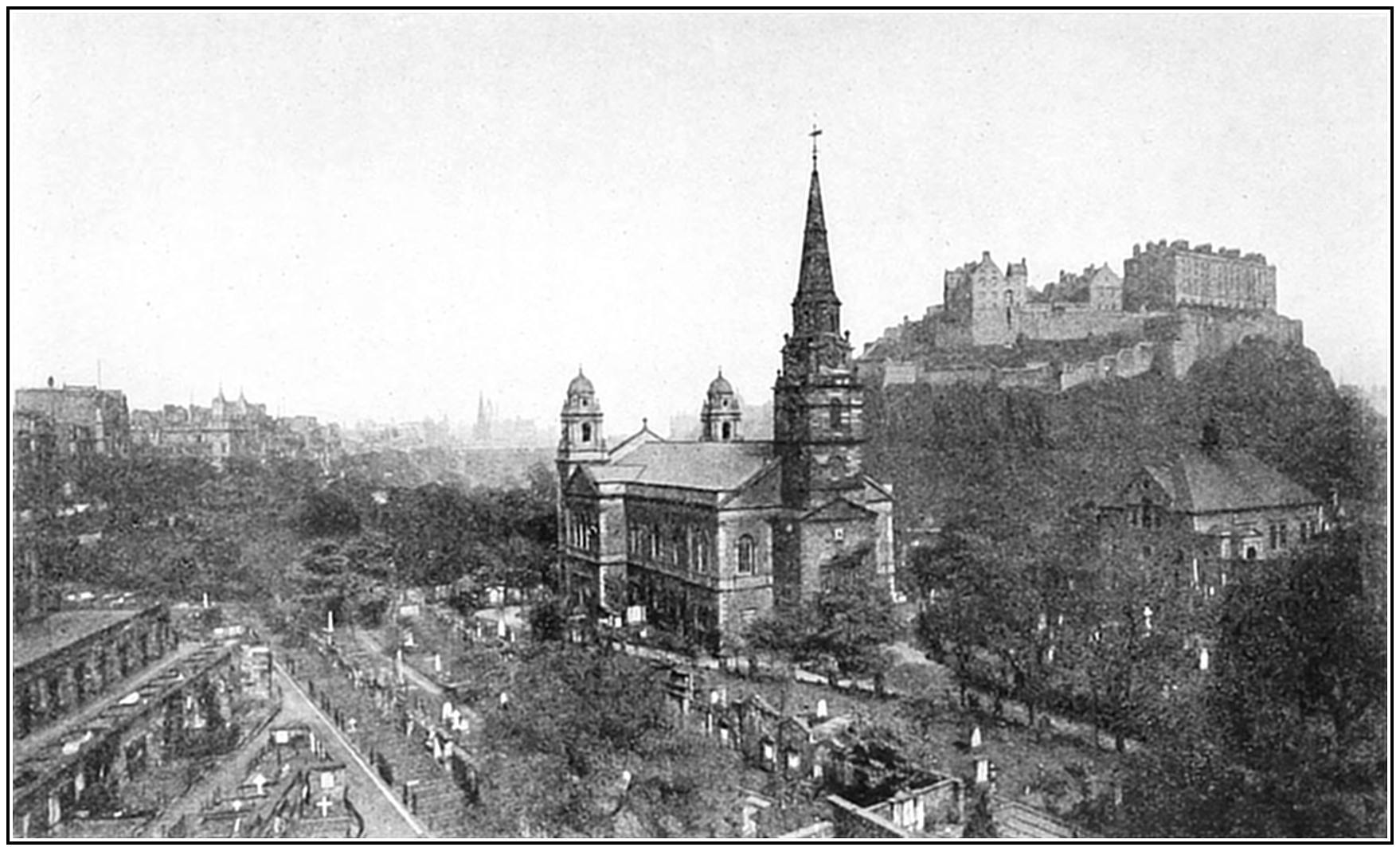

| Edinburgh City and Castle | 28 |

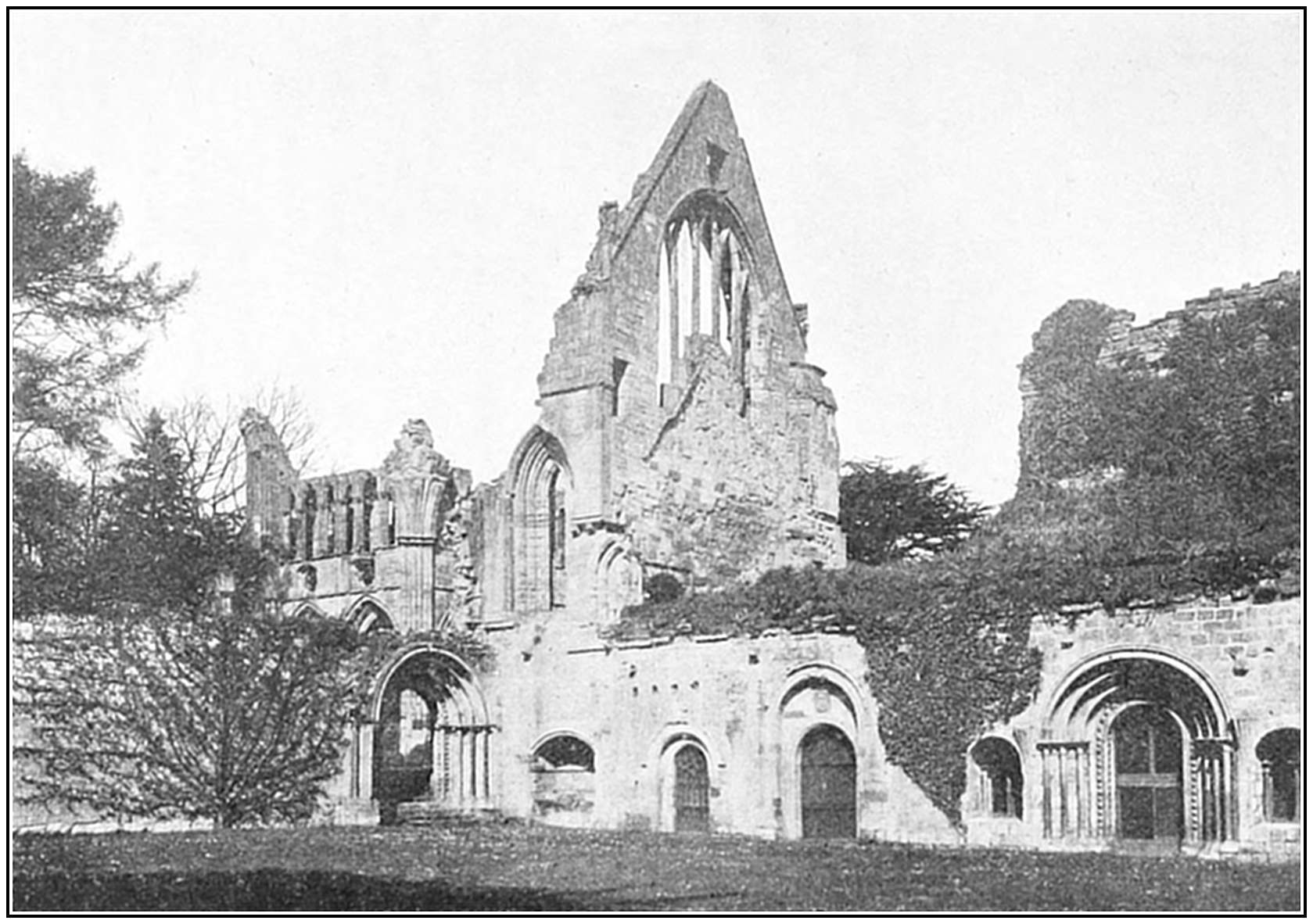

| Dryburgh Abbey | 44 |

| Abbotsford | 62 |

| The Monastery, Dunfermline Abbey | 70 |

| The Valley of the Tay | 84 |

| A Typical Scottish Street: High Street, Dumfries | 94 |

| Stirling Castle, from the King’s Knot | 100 |

| The Kings’ Graves, Iona | 128 |

| The Cairn at Culloden | 148 |

| The Scotch Brigade Memorial | 174 |

| Interior of Cottage, Northeast Coast | 194 |

| The Harbor of Kirkwall, Orkney Islands | 202 |

| The Trossachs and Loch Achray | 216 |

| The Tam o’ Shanter Inn, Ayr | 226 |

| The Edinburgh Conference of Missions | 268 |

BONNIE SCOTLAND

CHAPTER I

THE SPELL OF THE INVISIBLE

As with so many of my countrymen, the dream floated before the vision dawned. The American who for the first time opens his eyes in Europe is like the newborn babe, whose sight is not yet focused. He sees double. There is continually before him the Old World of his fancy and the Europe of reality. War begins, as in heaven, between the angels—of memory and of hope. The front and the rear of his brain are in conflict. While the glamour of that initial glimpse, that never-recurring moment of first surprise, is before him, he perforce compares and contrasts the ideal and the reality, even to his bewilderment and confusion. Only gradually do the two beholdings coalesce. Yet even during the dissolving pictures of imagination and optical demonstration, that which is present and tangible wins a glory from what is past and unseen.

From childhood there was always a Scotland which, like Wordsworth’s “light that never was, on sea or land,” lay in my mind as “the consecration and the poet’s dream,” of purple heather, crimson-tipped daisies, fair lasses, and brave lads. It rose out of such rainbow tints of imagination and out of such mists of fancy as were wont to gather, after reading the poets and romancers who have made Scotland a magnet to travellers the world over. This far-off region, of kilts and claymores, first sprang out of the stories of friends and companions. Our schoolmates, whether born on the moor or sprung from Scottish parents in America, inherited the love of their fond forebears and kinsmen, who sincerely believed that, of all lands on this globe, Bonnie Scotland was the fairest.

One playfellow, who afterwards gave up his life at Bull Run for the land that had given him welcome, was my first tutor in Scottish history. If native enthusiasm, naïve sincerity, and, what seemed to one mind at least, unlimited knowledge, were the true bases of reputation, one might call this lad a professor and scholar. As matter of fact, however, we were schoolboys together on the same bench and our combined ages would not amount to twenty-five. He it was who first pictured with vivid phrase and in genuine dialect the exploits of Robert the Bruce and of William Wallace. He told many a tale of the heather land, in storm and calm, not only with wit and jollity, but all the time with a clear conviction of the absolute truth of what had been handed down verbally for many generations.

He it was who, without knowing of the books written in English which I afterwards found in my father’s rich library of travel, stirred my curiosity and roused my enthusiasm to read the “Scottish Chiefs” and Sir Walter’s fascinating fiction, and, by and by, to wander over the flowery fields of imagination created by that “illegitimate child of Calvinism,” Robert Burns.

Though the boy who became a Union soldier was the first, he was by no means the last of Scottish folk whose memories of the old country were fresh, keen, and to me very stimulating. In church and Sunday school, in prayer-meeting and Bible class, I met with many a good soul who loved the heather. I heard often the words of petition and exhortation that had on them the burr and flange of a pronunciation that belonged to the Lowlands. As years of experience and discrimination came, I could distinguish, even on American soil, between the Highlander’s brogue and the more polished speech of Glasgow and Edinburgh.

When the time for college preparation came, I had, for private tutor in the classics, a theological student, who in physical frame and mental traits, as well as in actual occupation, was Hugh Miller all over again. He had been a stonecutter, believed in “the testimony of the rocks,” and could lift, move, or chisel a block of mortuary material with muscles furnished for the occasion. In character, he resembled in hard beauty the polished rose-red granite of his native hills. Strictly accurate himself, a master whose strength had grown through his own surmounting of difficulties, he was not too ready to help either a lazy boy or an earnest student, while ever willing to give aid in really hard places. He introduced me to Xenophon, and his criticisms and comments on the text were like flashlights, while his sympathy for Klearchus and his comrades illuminated for me my own memories of the camp life, the hard marching, and the soldier’s experiences during the Gettysburg campaign. From the immortal Greek text he made vivid to me the reality of human relations and their virtual identity, whether in B.C. 400 or A.D. 1863.

By this Scotsman I had a window opened into the Caledonian mind in maturity. Through him I realized something, not only of its rugged strength, its sanity, and its keen penetration, but I gained some notion also of the Scottish philosophy of common sense, which so long dominated colonial America and especially Princeton—the mother of statesmen and presidents, over which McCosh presided in my earlier days.

It was this Caledonia of mind, made by the deposits of human thought through many ages and experiences, which seemed and yet appears to me as an eternal Scotland, which, despite change of fashions, of wars and calamities, shall never pass away. So I must confess to the spell of invisible Scotland, as well as to the fascination of the storm-swept peninsula of heaths and rugged hills.

Besides boyhood’s companions of Scottish blood and descent, there were odd characters in the Pennsylvania regiment in which I served as flag corporal. My comrades under the Stars and Stripes came from various shires of Caledonia. Then, too, besides the bonnie maidens, like those Burns and Ramsay talked with, whose ancestry I knew, because I was often in their homes and met their parents and their kinsmen, there was the glamour of the dramatic poet’s creation. Immediately in front of my father’s home, in Philadelphia, was the famous Walnut Street Theatre, where that mighty figure in histrionic art, Edwin Forrest, was often seen. The tragedy of “Macbeth,” which I have seen rendered more times by famous actors than I have seen any other of Shakespeare’s creations, gave a background, which built in my imagination a picture of Scotland that had in it the depths of eternal time. The land and people had thus a perspective of history such as nothing else could suggest, even though I knew enough of the background of actual record to realize that Shakespeare’s chronology often passed the limits of Usher.

So with boyhood’s memories and the reading of poets and romancers, with the more or less undefined horizons of picture, painting, book, and the drama, reinforced by what a college student might be supposed to have absorbed, I was ready for wondrous revelations when, with Quandril, my eldest sister, I embarked in the Scottish Anchor Line steamer Europa, Captain Macdonald, master, on the 26th of June, 1869. It was after graduation and at the end of the month of roses. We were bound for the land of Macbeth, Bruce, Wallace, Scott, and Burns.

CHAPTER II

THE OUTPOST ISLES

It was fitting that our first sight of the Old World should be also that of the homeland of those who settled the Scottish Peninsula. It is commonplace knowledge that, until well into the Middle Ages, Europe’s most western isle was called “The Land of the Scots.” Not until after the Norsemen had frequently visited this “Isle of the Saints” was Ireland called by its modern name. From the ocean outpost, the natives left their ancestral seats and crossed to a strange land—the larger island of Britain, of which the northern half became in time the country now, and for nearly a millennium past, known to the world as Scotland.

One wonders what his first sensations will be when he approaches the mother continent. Some, with keen olfactories, in a seaward breeze, smell the burning turf, which tells of homes and firesides and human companionship. We looked for the land birds. Blown out over the waves, these feathered messengers find shelter in the ship’s rigging and welcome from sea-weary passengers.

To us, they were our first visitors. A terrific storm had for a day and night lashed the ocean into fury, split one of our booms and stove in a lifeboat, only to be succeeded by a morning of sunny splendor. Then both ocean and sky seemed like twin sapphires. The tossing spray, which in the sunbeams showered dust of rainbows, gradually gave way to calm. Toward noon we welcomed two little feathered messengers. They were made happy by finding rest aloft in the shrouds. A third, too exhausted to guide its course, fell upon deck. We kept our eyes aloft, waiting for news from the crow’s nest. Yet while we, with the old sea dogs, captain and crew, were looking alternately forward and upward, as yet discerning nothing, a sailor, born in Michigan, who was the lookout for the day, called out “Land ho!”

For the next few minutes we were contestants in a game of rivalry, as to which eyes should see first and best. Not many minutes sped, however, before most of us had discerned a long, low, cloudlike line, which, instead of shifting its form, like its sister apparitions of the air, loomed on the horizon in fixed defiance of change.

As if to tantalize us, fresh breezes soon condensed new vapors and the land disappeared from view. Again, for hours, we were in mist and fog, but at high noon, the veil was lifted suddenly. There before us, rising sheer out of the ocean and apparently but a mile or two away, was the great green glory of Ireland. Like a mountain of emerald rising out of a sapphire sea, stood the land whose name and color, in sentiment and in reality, is Nature’s favorite, earth’s best counterpart to the sky.

After seeing the Giant’s Causeway, meeting the paddle-wheel steamer from Londonderry, and passing Rathlin Island,—refuge once of Robert the Bruce,—we sight the real land of our quest when we discern the larger isle of Arran, which rises like a minaret out of the sea. In law and geography, as well as the outpost of history, it is recognized as an integral part of Scotland. Still alertly peering eastward, we behold in the thickening dusk the mainland, whereupon our hats rise in salute to Bonnie Scotland. The sun here does not set till nine o’clock in the evening and sinks to-night amid clouds which break into spires and turrets. These, in the crimson glow, look like some sea-girt castle in flames.

We are on the lookout for anything and everything that may remind us of Robert the Bruce, for in the history of Arran the chief name is that of Scotland’s heroic king. On its western coast he found shelter in what are still called the “King’s Caves.” Of a trio of these he made a regular apartment house; for one bears the name of his kitchen, another of his cellar, a third of his stable. On the land higher up is the “King’s Hill,” and from a point called the “King’s Cross,” he crossed over to Carrick, when the long-awaited signal told him that the moment for the liberation of his country had come. In Glen Cloy, near by, his trusty followers lay concealed, and the picturesque ruins still bear the name of “Bruce’s Castle.” Other masses of ruins on Loch Ranza are pointed out as representing what was his hunting-seat. Are the Scots of Arran as greedy to boast of as many places made famous by Bruce as are Americans of Washington’s headquarters?

The name of Bruce is not the only one in the long and glorious annals of Scotland that clings to Arran. The earls of this insular domain were nearly all members of the famous Hamilton family which gave so many eminent men and women to Scotland and England. How many more of their shining names are as stars in the firmament of our national history! The champion of free speech, who owned the land which is now Independence Square in Philadelphia, and whose eloquence in New York city acquitted the German editor Zenger in the great trial which inaugurated and perpetuated free speech in America, was a Hamilton. As the greatest constructive political genius known to our country, the virtual father of the United States Government, the name of Alexander Hamilton is an inspiration to the Unionists of Great Britain to-day.

Back of the pear-shaped island of Pladda—which we passed and whose telegraph station notified Greenock and Glasgow of our arrival in the Clyde—are ancient standing stones, or cairns, and many a memorial of remote antiquity which witness to very early habitation by man on this outpost island.

In the eyes of those to whom the past furnishes a perspective more fascinating even than the promise of the future, the little isle adjacent, which is itself a finely marked basaltic cone, rising over a thousand feet high and well called “Holy Island,” is even more worthy of the visits of the reflecting scholar. It holds an attraction even greater, in human interest, at least, than the wonders of geology, or the numerous witnesses to antiquity in the form of upreared stones. Here St. Molios, a disciple of St. Columba, founded a church. In the Saint’s Cave, on the shore, may still be seen the rocky shelf on which he made his bed. Like the outraying sparkles of light from a gem, the lines of influence from this saint’s memory have flashed down the ages. To-day from sections of the Christian Church, “high” or “low,” and from Christian “bodies” with sectarian names, as many as the letters of the alphabet, come visiting pilgrims or happy tourists to pay their debt of admiration, or to refresh for a moment their traditional faith. In that wonderful sixth Christian century—as remarkable in Asian and Buddhist, as in European and Christian history—Ireland (not then known by that name, but the old “Land of the Scots”) was a shining centre of gospel light and truth. Moreover, it was a hive of missionary activities, sending off swarms of “apostles.” Happily, this word means missionaries and nothing else, connoting spiritual activities and not questions of authority, over which paid ecclesiastics will ever and in all lands wrangle lustily.

In modern days, the whole island is peaceful. So far has the old Gaelic speech passed into “innocuous desuetude,” that at the opening of this century only nine persons were left who could use but this one speech, though over a thousand natives could speak both English and Gaelic. Instead of the tranquil calm of to-day, however, few islands have been oftener stained with the blood of warriors and quarrelling clansmen. We who imagine that only the dark-skinned nations were savages must remember how recently both Englishmen and Scotsmen emerged from barbarism. It was but in the yesterday of historic time that Christians burned one another alive, in the same spirit that worshippers of Moloch cast their children into the red-hot stomach of their brazen idol, or Hindu mothers fed their babies to the crocodiles. How numerous were the Scottish assassins and victors who carried the heads of their enemies as trophies on the top of pikes, like the Indians and Pilgrims of colonial days! Yet no literature excels that of the Scots, in the perfect frankness with which the sons of the soil confess their recent emergence from barbarism into the admired civilization of to-day.

Thus the initial spell of the Scottish landscape lay first of all upon us who had known Scotland only through books or by word of mouth. Yet to such the human appeal is immense. Who can look upon this egg-shaped island of Arran, with its jagged peaks and its singularly grand scenery, without emotion? The conformation, as seen only in part from the ship’s deck, appears shaggy, because so mountainous and heathy, with many a romantic glen and promontory; and there are picturesque masses of columnar basalt forming a link between the Giant’s Causeway and Staffa’s wonder. In fact, we are told by the scientific men that the geology of Arran is almost unique, displaying as it does a greater succession of strata than any other single portion of land of equal extent, in the whole area of the British Isles.

In the gathering twilight, even though this was prolonged, so that a lady could see to thread a needle at 9.30 P.M., we catch glimpses of this appendix to the land of Burns; for Arran belongs in the poet’s native shire. In later years nearer views enabled us to see again the trap rock, the granite, and the slate, and to catch a glimpse of some of the streams, one of which falls over a precipice more than three hundred feet high. In truth, the first impression of Arran furnished even less delight than those in later years, when we were saturated with Scottish lore; then the island spoke with new tongues and even more eloquently than at first sight, of nature and human history.

We had left Ireland the day before, steaming out from the Giant’s Causeway. Our steamer ploughed her way, and perhaps may have cast anchor during the night. In any event, after breakfast, we were well into the Firth of Clyde. In sunlight and in joy we moved swiftly up the river of the same name. At Greenock, during a pause, we saw granite docks. These, in contrast to the wooden wharves of New York, mightily impressed us with the solidity and permanence of things in the Old World, though there were enough smoky foundries to make the air black. At Greenock, Burns’s “Highland Mary” is buried, but is elsewhere glorified in a statue. Rob Roy once raided the town, which has history as well as romance. To us, on that day of first sight, the chief interest of Greenock lay in the fact that our honored Captain Macdonald, of the Europa, had his home here. Brave man! He was afterwards lost at sea and at the post of duty, when a colossal wave, sweeping the ship, carried away the bridge and the officers on it!

We steam up the river as rapidly as is safe in a crowded, narrow channel. Our ship is now in fine trim. Her masts have been scraped, her decks scrubbed, and her sails enclosed in white canvas covers, while from every mast floats a flag—the Stars and Stripes over all. Swift river steamers shoot past us and ten thousand hammers ring in the chorus of labor on the splendid iron and steel vessels, which are the pride of Scotland and of world renown. We pass Cardross Castle in which Robert the Bruce died—the last two years of his life being written, as in the biography of Naaman—“a mighty man, but a leper.”

On a high rock, nearly three hundred feet high, looms Dumbarton Castle, which has played so notable a part in Caledonian history. Even when Scotland joined the Union and became one with Great Britain, this was one of the four fortresses secured to the Land of St. Andrew, whose cross was laid on that of St. George to form the British flag. Here Wallace was betrayed and kept a prisoner. Here they have his alleged two-handed sword, now known to be a spurious relic. Not many miles away is Elderslie, his birthplace.

Touching one’s imagination even more profoundly are the ruins of the old Roman wall built across the lower end of Scotland, which we pass as we sail by. The bright ivy covers it luxuriantly, and as the summer breeze kisses its surface, the lines of living green ripple, and dimple, and disappear in the distance along verdant miles. How it recalls the far past,—

Aloft is a monument, to which we take off our hats, in honor of Henry Bell, who introduced steam navigation into Europe.

Many times afterwards did we see the Clyde and its great monuments of industry and history. Yet one’s first impressions are almost always the most vivid, and from this initial experience, which holds longest the negatives of memory, are printed the brightest pictures. It was two o’clock when we moored off the dock. Passing the slight examination of the polite custom-house officers, we stepped once more upon solid earth,—the land of Burns and Scott.

CHAPTER III

GLASGOW: THE INDUSTRIAL METROPOLIS

“There is nothing so certain as the unexpected.” Our first impression, after stepping upon the dry land of Europe, was that it was “limited.” Not that we had been obsessed by the spirit that dwelt in that reinforced Western Yankee, who, while on the island of Britain, was afraid to go to sleep o’ nights lest he might fall off! Yet in Glasgow the word “Limited” stared at us from every shop sign. We had not yet in America adopted the statute of financial limitations for trading firms, but the laws of the United Kingdom even then required that any one doing business with a limited capital or accountability, must state the fact on his shop sign or other public announcement. It was this frequent expression of commercial conditions, then a real novelty, that attracted our initial attention.

It was the day before Scotland’s Sabbath, or, in local dialect, “Sunday First,” that we had our virgin view of Glasgow, and the excellent custom of a Saturday half-holiday was in vogue. This afforded us all the more ease in seeing the principal thoroughfares, which, with the crowd absent and the shops closed, made comfort, but gave to the lengthened areas a deserted look. We sauntered into St. George’s Square, where, in addition to the imposing buildings surrounding it, rises the lofty column on which stands the bronze effigy of Sir Walter Scott. How marvellously did this Wizard of the North delight millions, through many generations, with his poetical numbers and his weird romances! To-day, his name is a magnet that annually brings to Scotland thousands of tourists and millions of dollars. In the long run there are no more valuable assets to a country than its great men and its deathless literature.

There were other statues visible at this time, but the larger number of those which to-day run the risk of being destroyed by bombs from the empyrean, in the new fashions prevalent in aerial warfare, were not then in existence. So it was to the cathedral that we hied, partly for the reason that this was to be the first of the many great sacred and historic edifices to be seen by us in the Old World, but chiefly because the hoary pile was almost the only one which survived the tumult and destruction of the Reformation. Largely by the “rascal multitude,” as Knox called the mob, but also in the then prevalent conviction that these structures, as then used, had survived their original purpose, and should be reduced to ruins, cathedrals, abbeys, and monasteries were levelled. For her size, no country excels Scotland in ruins.

The Glasgow cathedral, in slow evolution during centuries, was never finished. For a time its inner area was divided off to make worship more comfortable and also to bring the structure into closer conformity with those new fashions in religion, according to which the people were given sermons, instead of masses, with more worship through the intellect, and less through the senses and emotions. Yet as we stood within its cold, damp walls, on that July afternoon, we wondered how long human beings, unless clothed in plenty of woollen habiliments, could sit or stand on its stone floor. Despite its age, the interior had an air of newness, indeed, almost of smartness, for its architectural restoration and interior cleansing had been recent. The modern stained glass, made largely in Munich, though very rich, had not yet softened down into the mellowness which only centuries can bestow. One noted that the subjects selected and grandly treated with the glory, yet also within the historic limitations, of the artist in stained glass, were wholly taken from the New Testament. These Biblical and eternally interesting subjects compel thought and provoke contrast with the more garish themes of the modern world.

Going out from the great cathedral, and its wonderful crypt, we visited the Necropolis, Glasgow’s beautiful city of the dead. Being set upon a hill, it cannot be hid. Laid out in the form of terraces, and with many imposing monuments, it challenges our attention. Here sleep the merchant princes of Glasgow and the mighty dead of Scotland. The tombs are of the most costly character, for the most durable materials in nature have been summoned to record facts and to defy oblivion. Everything which love of beauty, chaste refinement, and abundant wealth could command has been wrought with toil and taste to make this lovely home of those at rest a fit resting-place for the brave men and women who are still unforgotten. The long roll of their names forms the brightest page in Scotland’s history, and the native, even when far from home, dearly loves to remember them. On a lofty Doric column, high over all else, is a statue of John Knox, and on its base is the thrilling inscription:—

“Here lies one who never feared the face of mortal man.”

Among the names, read at random on the sculptured stone, were those of Sheridan Knowles, Dr. John Dick, Melville the reformer, and many others familiar and honored in Scottish history. Thus, as out of the past centuries does the old cathedral, so, in the modern day, do the shining monuments of the departed dead look down upon the bustling life that goes on noisily below. One here feels that the spell of Scotland is not only in nature’s glories, but in the matchless landscape of her thought; nor is the empire of Scottish intellect one whit less fascinating than that of her lochs, her moors, her heather, or her granite hills. What Scotland has contributed to religion, in both theoretical study and in fruitage of practical results, argues well for world-unity. Our debt as Americans to her thought is immeasurable.

The next day is the Sabbath. The chimneys are asleep, and after the showers of the night before, even the air seems washed clean. “Like a spell,” the “serene and golden sunlight” lies over land and sea. One can now readily accept another line of verbal genealogy. Remembering that coal smoke is, after all, very modern, and chemical fumes recent, it is easier to believe that “Glasgow” is not derived from words meaning “dark glen,” but is only a modified form of the old Celtic word Gleshui, or Glas-chu, which means “dear green spot,” from glas, green and chu, dear.

Indeed, there are antiquarians who tell us that when the first Christian missionary, St. Kentigern, came to convert the Britons of Strathclyde, this antique term, expressing affection for the place and its beauty, became the name of the settlement. In days when the efficiency of particular saints was believed in more than now, and before the great American god Prosperity was so worshipped, and before both we Yankees and the people whom Napoleon bundled together as “a nation of shopkeepers” did so bow before the golden calf, every city, town, and even village had its patron saint.

Such an association of ideas—of connecting public welfare with holy men and prosperity with obedience to their exhortations—was perhaps fully as reasonable as is the modern desire of our City Councils and Boards of Trade for railways, electric lights, and the location within their municipal bounds of factories and commercial establishments. Even villages then welcomed the monks with free hand, much as our towns boom their reputation by offering building-sites free to those who will locate. So also the reason why in Europe we find so slight a variety of names for boys and girls, and why in certain regions particular local names are so frequently repeated, is because of the zeal and industry of certain old-time saints. According to the popularity of the holy man or woman was the census of boys’ and girls’ names—as, for example, in Holland, Kilaen and Fridolin; in France, Henri or Denis; in Ireland, Patrick and Bridget; in England, George and Mary; and in Scotland, Mungo, Andrew, or some other Christian name once borne by a spiritual pioneer, whose story is one of inspiration.

In such a climate and era of opinion, Glasgow took for its patron saint, Mungo, and the municipal motto and arms are wholly identified with his career. “Let Glasgow flourish by the preaching of the Word” was his verbal gift and bequest, though in ordinary use and conversation the municipal motto is shortened to “Let Glasgow flourish.” This is very much as in the Netherlands the national motto, once much longer, is now abbreviated to two words in Dutch (or rather French) which in English mean “I will maintain.” Our own native city has the advantage of having adopted that scriptural command, or desire, which begins a famous chapter in Hebrews, “Let Philadelphia continue.”

Kentigern, whose name meant “chief lord,” was one of the three pioneer apostles or missionaries of the Christian faith in Scotland. Ninian took as his task the converting of the tribes of the south; St. Columba was the apostle of the west and north; while Mungo restored or established the religion of the British folk in the region between the Clyde and Cumberland. Of high birth and of early British stock, he saw the light at Culross in the year 514. His mother Thenau was the daughter of a saint of the Edinburgh region. So dearly was he beloved by the monastic brethren that his baptismal name of Kentigern was exchanged in common speech for Mungo, meaning “lovable,” or “dear friend.” Leaving Culross, he made use of the chief forces of missionary propagation in that age, by planting a monastery at a place now known as Glasgow. He became bishop of the kingdom of Cumbria, as the region, partly in the later-named England and partly in Scotland, was then called.

When this holy missionary lived, there were no such specific regions, with boundaries fixed by surveyors and known as England and Scotland, nor were Highlanders or Lowlanders discriminated by any such later and useful terms of distinction. The region which Mungo first entered was called Cumbria and was then and long afterwards an independent kingdom. It has since been broken up into Cumberland in England, and that part of Scotland which is now divided into the shires of Dumbarton, Renfrew, Ayr, Lanark, Peebles, Selkirk, Roxborough, and Dumfries. The name of Cumbria, notably differentiated from what in recent centuries has been called England, was governed by its own kings, who had their seat at Dumbarton or Glasgow. The name still lingers in the Cumbria Mountains. In this great knot of peaks and hills lies the famous British “lake district,” which is very much in physical features like Wales, being unsurpassed in the British archipelago for picturesqueness and beauty.

When the varied Teutonic tribes—Saxons, Angles, Frisians, Jutes, and what not from the Continent—pressed into the Lowlands, the natives inhabiting the western and more mountainous districts, north of the Forth and the Clyde, had to be distinguished from the newcomers. Then it was that these people of the hill country received names not altogether complimentary. They were called the “Wild Scots” or the “Irishry of Scotland,” and only in comparatively recent times “Scotch Highlanders.” The last prince of Cumbria, named in the records, was the brother and heir of King Alexander I of Scotland.

Glasgow is really a very modern city. As the city on Manhattan is the evolution from a fortress, so the cathedral was the nucleus around which the ancient town of the “dark glen” grew. The university, when founded, became also a magnet to attract dwellers. In the twelfth century, King William the Lion erected the settlement into a burgh, with the privilege of an annual fair. Yet even down to the sixteenth century, Glasgow was only the eleventh in importance among Scottish towns. It was the American trade, after the union with England, which gave an immense stimulus to its commerce. If “Amsterdam is built on herring bones,” the Scottish city became rich through the tobacco leaf. For a long time the merchants of Glasgow, who traded with Virginia, formed a local aristocracy, very proud and very wealthy. For a century or more, this profitable commerce lasted. Then our Civil War paralyzed it, but other industries quickly followed.

The permanent wealth of Glasgow comes, however, from its situation in the midst of a district rich in coal and iron. Furthermore, the improvements made in the steam engine by James Watt, and the demonstration, by Henry Bell, that navigation with this motive power was possible, wrought the transformation of Glasgow into the richest of Scottish cities. Speaking broadly, however, as to time, Glasgow’s wealth is the creation of the nineteenth century, and its influence upon the world at large is not much older. As upon a ladder, whose rungs are sugar refining, the distillation of strong liquors, the making of soap, the preparation of tobacco, the introduction of the cotton manufacture, calico printing, Turkey-red dyeing, beer-brewing, and the iron trade, including machine-making and steamboat building, the prosperity of Glasgow has mounted ever upwards.

The tourist seeking rest, refreshment, and inspiration is but slightly interested in mere wealth or prosperity that is wholly material. So, despite the attractive solidity of its houses, built of free-stone, and of its streets running from east to west, in straight lines and parallel with the river, the city of Glasgow, with its dingy and ever smoky aspect, has little to attract the traveller whose minutes are precious and whose days on the soil are few. So on this first visit, a day and a night sufficed us, and then we left the burgh of the (once) dear green spot and took the train to “Edwin’s burgh,” or Edinburgh.

Many times did we revisit Glasgow, noting improvement on each occasion. We came to consider this the model city of Great Britain in its municipal spirit and constant improvement. We blessed the Lord for electricity which is steadily annihilating smoke and brightening the world. “The city is the hope of democracy.”

CHAPTER IV

EDINBURGH THE PICTURESQUE

It was late in the afternoon when we first arrived in the most beautiful city in Scotland, and the sun’s rays lay nearly level. Between the old town on the hill—inhabited and garrisoned, perhaps, from prehistoric times and sloping down from the castle-crowned rock—and the new modern fashionable quarter, with sunny spaces and broad avenues, runs a deep ravine. In old times this depression contained a lake called the “Nor’ Loch,” which, having been drained long ago, is used by the railways. Thus entering Edinburgh, by the cellar, as it were, we must ascend several pairs of stairs from the Waverly Station, to reach the ordinary street level.

Seeing far above us the hotel to which we wished to go we walked up skyward toward it. At the top of the stairs, turning to look, we were at once “carried to Paradise on the stairways of surprise.” One of those moments in life, never to be forgotten, as when one beholds for the first time Niagara, or has his initial view of the ocean, or stands in presence of a monarch, was ours, as we gazed over toward the old city and the cloud-lands of history. We had known that Edinburgh was handsome, historic, and renowned, but had not dreamed that it was so imposing, so magnificent, so unique in all Europe.

Beneath us lay the long, deep ravine, now threaded with the glittering metal bands of the railway and planted with parks and gardens brilliant with flowers. High on the opposite bank, and sweeping up toward the summit, lay the old city. Its lofty irregular masses of stone buildings and towers, with the castle crowning all, seemed like a mirage, so weird and unearthly was this unexpected appearance of “the city set upon a hill.”

We gazed long at the enchanting sight and then turned to visit the chief avenue of the new city, Princes Street—a perfect glory of attractive homes, with broad spaces rich in gardens and statuary, the whole effect suggesting taste and refinement. This we believe, despite Ruskin’s fiery anathema of modern taste.

A splendid monument to Sir Walter Scott, three hundred feet high and costing $90,000, stands in the centre of the space opposite our hotel. Though in richest Gothic style and a gem of art, it was built by a self-taught architect. Not far away, Professor Wilson, Allan Ramsay, Robert Burns, and other sons of Scotland repose in bronze or marble dignity. Indeed, the new city is particularly rich in monuments of every description and quality. Edinburgh’s parks and open spaces are unusually numerous. Even the cemeteries are full of beauty and charm, for it is a pleasure to read the names of old friends, unseen, indeed, but whom we learned to love so long ago through their books.

To-day the American greets in bronze his country’s second father, whose ancestors once dwelt on the coin, or colony on the Lind; whence Father Abraham’s family name, Lincoln. How we boys, in the Union army in 1863, used to sing, “We are coming, Father Abraham, three hundred thousand strong”! How in 1916, the men of the four nations of the United Kingdom, who have formed Kitchener’s army, sang their merry response to duty’s call, in the same music and spirit, and in much the same words!

Edinburgh is really the heart of the old shire of Midlothian, for it is the central town of the metropolitan county, with a long and glorious history. After James I, the ablest man of the Stuart family, was murdered, on Christmas night, A.D. 1437, Edinburgh became the recognized capital of the kingdom, for neither Perth, nor Scone, nor Stirling, nor Dunfermline was able to offer proper security to royalty against the designs of the turbulent nobles. From this date Edinburgh, with its castle, was selected as the one sure place of safety for the royal household, the Parliament, the mint, and the government offices. Thereupon in “Edwin’s Burgh” began a growth of population that soon pressed most inconveniently upon the available space, which was very restricted, since the people must keep within the walls for the sake of protection. The building of very high houses became a necessity. The town then consisted only of the original main way, called “High Street,” reaching to the Canon Gate, and a parallel way on the south, long, narrow, and confined, called the “Cow Gate.” It was in the days when the sole fuel made use of was wood that Edinburgh received its name of “Auld Reekie,” or “Old Smoky.”

In other words, feudal and royal Edinburgh was a walled space, consisting of two long streets, sloping from hilltop to flats, with houses of stone that rose high in the air. Somehow, such an architectural formation, which might remind a Swiss of his native Mer de Glace and its aiguilles, recalls to the imaginative but irreverent American the two long parallel series of rocks, which he may see on the way to California, called “The Devil’s Slide.” These avenues of old Edinburgh, so long and not very wide, had communication each with the other by means of about one hundred dark, narrow cross-alleys or “closes,” between the dense clusters of houses. Sometimes they were called “wynds,” and in their shadowy recesses many a murder, assassination, or passage-at-arms took place, when swords and dirks, as in old Japan, formed part of a gentleman’s daily costume. In proportions, but not in character or quality of the wayfarers, these two Scottish streets are wonderfully like the road to heaven.

These houses were not homes, each occupied by but one family. They were rather like the modern apartment houses, consisting of a succession of floors or flats, each forming a separate suite of living-rooms, so that every structure harbored many households. Of such floors there were seldom fewer than six, and sometimes ten or twelve, the edifices towering to an immense height; and, because built upon an eminence, rendered still more imposing. It was toward the middle of the eighteenth century before the well-to-do citizens left these narrow quarters for more extensive and level areas beyond the ravine. There is now no suggestion of aristocracy here, for these are now real tenement houses. The hygienic situation, however, even though the tenants are humble folk, reveals a vast improvement upon the days when elegant lords and ladies inhabited these lofty rookeries, which remind one of the Cliff Dwellings of Arizona—or those modern “cliff dwellings,” the homes of the luxurious literary club men on the lake-front of Chicago.

In old days it was a common practice to throw the slops and garbage out of the upper windows into the street below. The ordinary word of warning, supposed to be good Scotch and still in use, is “Gardeloo,” which is only a corruption of the French “Gardez de l’eau” (Look out for the water). It is but one of a thousand linguistic or historic links with Scotland’s old friend and ally, France.

In fact, until near the nineteenth century, Edinburgh’s reputation for dirt, though it was shared with many other European cities in which our ancestors dwelt, was proverbial, especially when refuse of all sorts was flung from every story of the lofty houses. From the middle of the street to the houses on both sides lay a vast collection of garbage ripening for transportation to the farms when spring opened. In this the pigs wallowed when driven in, at the close of the day, from the beech or oak woods by the hog-reeve. The prominent features of the prehistoric kitchen middens, which modern professors so love to dig into, were, in this High Street, in full bloom and the likeness was close.

How different, in our time, when municipal hygiene has become, in some places at least, a fine art! There is a reason why “the plague” no longer visits the British Isles. Nor, as of old, is “Providence” so often charged with visiting “mysterious” punishment upon humanity. Science has helped man to see himself a fool and to learn that cleanliness is next to godliness. The modern Scot, for the most part, believes that laziness and dirt are the worst forms of original sin. Yet it took a long course in the discipline of cause and effect to make “Sandy” fond of soap, water, and fumigation. In this, however, he differed, in no whit, from our other ancestors in the same age.

After seeing Switzerland, and studying the behavior of glaciers, with their broad expanse at the mountain-top, their solidity in the wide valleys, and then, farther down, their constriction in a narrow space between immovable rocks, which, resisting the pressure of the ice-mass, force it upward into pinnacles and tower-like productions, I thought ever afterwards of the old city of Edinburgh as a river, yet not of ice but of stone. Flowing from the lofty summit whereon the castle lay, the area of human habitation was squeezed into the narrower ridge, between ancient but now valueless walls, which seemed to force the human dwellings skyward. Yet it was not through the pressure of nature, but because of the murderous instincts of man, with his passions of selfishness and love of destruction, that old Edinburgh took its shape.

On our first visit, to cross from our hotel in the new city and over into the ancient precincts, we walked above the ravine, over a high arched stone bridge, and turning to the right climbed up High Street to the castle, and rambled on the Esplanade. This is the picture—it is Saturday afternoon and a regiment of soldiers in Highland costume have been parading. Yet, besides the warriors, you can see plenty of other men in this pavonine costume, with their gay plaids, bare legs, and showy kilts. We hear a strange cry in the streets and then see, for the first time, the Edinburgh fishwoman in her curious striped dress of short skirts and sleeves, queer-looking fringed neck-cover, and striped apron. Her little daughter dresses like her, for the costume is hereditary. On her shoulders is a huge basket of fish bound by a strap over her head. These fish peddlers are said to be a strange race of people living, most of them, at Leith, and rarely intermarrying outside of their own community.

At the castle we see that the moat, portcullis, and sally port are still there. We pass through the outer defences, which have so often echoed with battle-cries and the clang of claymores, for this old castle has been taken and retaken many times. Reaching what are now the soldiers’ barracks, we see a little room in which Mary Queen of Scots gave birth to James the Sixth of Scotland and First of England, in whom the two thrones of the island were united. It seems a rough room for a queen to live in.

The ascent of High Street is much like climbing a staircase, resting on landings at the second, third, or fourth floor. When, however, one reaches the top and scans the glorious panorama, he feels like asking, especially, as he sees that the highest and oldest building is Queen Margaret’s Chapel,—a house of worship,—“Does God live here?”

Of all the places of interest which we saw within or near the great citadel, there was one little corner of earth, with rocky environment but without deep soil, set apart as a cemetery for soldiers’ pets and mascots. The sight touched us most deeply. Here were buried, with appropriate memorials and inscriptions, probably twenty of the faithful dumb servants of man, mostly dogs, from which their masters had not loved to part.

It compels thought to recall the fact that, in large measure, man is what he is because of his dumb friends. What would he be without the horse, the dog, the cow, the domesticated beasts of burden, and our dumb friends generally? Without the white man, the Iroquois of America and the Maoris of New Zealand would undoubtedly have arisen into a higher civilization, had they been possessed of beasts of draught or burden, or which gave food, protection, or manifold service. Could they have made early use of the wonderful gifts of the finer breeds of the dog and the horse, what steps of advancement might they not have taken? How far would the Aztecs, Incas, and Algonquins have advanced without domestic fowls and cattle? What would the Japanese islanders have been, without the numerous domestic animals imported from China in historic times? What would Europe and America be, bereft of the gifts they have both received from Asia?

How striking are the narratives of the early colonists in America, that reveal to us the fact that the aboriginal Indian had only a wolf-dog of diminutive size and slight powers, while the canine breeds of Europe not only showed more varied and higher qualities, but were larger in size. Of these strange creatures, the red men were usually more afraid than of their white owners. How surprising was the experience of the Mexicans, who, on beholding the Spanish cavaliers, cased in steel, thought the horse and the rider were one animal! What would South America and her early savages have been, if left without the friends of man imported from the Asian continent?

As at The Hague and at Delft, one notes with the statue of William the Silent the little dog that saved his life; so at Edinburgh we see at the feet of the effigy of Sir Walter, the poet and romancer, his favorite dog Maida. Few episodes are more touching than that of the dog Lufra, in Canto V of the “Lady of the Lake.”

After such a picture of mutual devotion between man and brute, it seems little wonder that in Scotland has been bred what is perhaps the noblest type of canine life. In the physical characteristics of speed, alertness, fleetness, the Scotch collie is second to none in the kingdom of dogs, while in the almost human traits of loyalty to his master and devotion to his interests, this friend of man crowns an age-long evolution from the wild. Happily in art, which is the praise of life, Scotland’s collie and hound have found the immortality of man’s appreciation. This is shown, not only in the word paintings of her poets and romancers, but on the canvas of Landseer, the Shakespeare of dogs. In the Highlands this English painter found some of his noblest inspirations.

Edinburgh, besides being a brain-stimulant, because it is the focus of Scottish history, is also a heart-warmer. Holyrood Palace, Arthur’s Seat, Grey Friar’s Churchyard, St. Giles’s Church, the University, Calton Hill—what memories do they conjure up, what thought compel? A Scottish Sabbath—how impressive! One can no more write the history of Scotland or pen a description of the country and people, and leave out religion, than tell of Greece or Japan and make no mention of art.

CHAPTER V

MELROSE ABBEY AND SIR WALTER SCOTT

Always fond of fireside travels, I had, many a time, in imagination, ridden with William of Deloraine from Branksome Hall, through the night and into the ruins of Melrose Abbey. His errand was to visit the grave of Michael Scott, whose fame had penetrated all Europe and whom even Dante mentions in his deathless lines. Now, however, I had a purpose other than seeing ruins. If possible, I was determined to pick a flower, or a fern, from near the wizard’s grave to serve as ingredient for a philter.

Does not Sir Walter, in his “Rob Roy,” tell us that the cailliachs, or old Highland hags, administered drugs, which were designed to have the effect of love potions? Who knows but these concoctions were made from plants grown near the wonder-worker’s tomb? At any rate, I imagined that one such bloom, leaf, or root, sent across the sea, to a halting lover, might reinforce his courage to make the proposal, which I doubt not was expected on the other side of the house. At least we dare say this to the grandchildren of the long wedded pair.

So glorified were the gray ruins of Melrose, in Scott’s enchanting poetry, that I almost feared to look, in common sunlight, upon the broken arches and the shafted orioles; for does not Scott, who warns us to see Melrose “by the pale moonlight,” tell us that

Yet the tourist’s time, especially when in company, is not usually his own, and for me, though often, later, at the abbey, the opportunity never came of visiting “fair Melrose aright,” by seeing its fascinations under lunar rays, or in

On the morning of July 11, we had our first view from the railway. The ruins loomed dark and grand. Approaching on foot the pile, closely surrounded as it was by houses and Mammonites and populated chiefly by rooks, the first view was not as overpowering as if I had come unexpectedly to it under the silver light of the moon. Yet, on lingering in the aisles within the ruined nave and walking up and down amid the broken marbles, imagination easily pictured again that spectacular worship, so enjoyed in the Middle Ages and beloved by many still, which makes so powerful and multitudinous an appeal to the senses and emotions.

The west front and a large portion of the north half of the nave and aisle of the abbey have perished, but the two transepts, the chancel and the choir, the two western piers of the tower, and the sculptured roof of the east end are here yet to enthral. I thought of the processions aloft, of the monks, up and down through the interior clerestory passage, which runs all around the church. Again, in the chambers of fancy, the choir sang, the stone rood screen reflected torch and candlelight, and the lamp of the churchman shed its rays, while the “toil drops” of the knight William, “fell from his brows like rain,” as “he moved the massy stone at length.”

A minute examination of the carving of windows, aisles, cloister, capitals, bosses, and door-heads well repays one’s sympathetic scrutiny, for no design is repeated. What loving care was that of mediæval craftsmen, who took pride in their work, loving it more than money! Proofs of this are still visible here. Such beauty and artistic triumphs open a window into the life of the Middle Ages. From the south of Europe, the travelling guilds of architects and masons, and of men expert with the chisel, must have come hither to put their magic touch upon the stone of this edifice, which was so often built, destroyed, and built again. “A penny a day and a little bag of meal” was the daily dole of wages to each craftsman. One may still trace here the monogram of the master workman.

Under the high altar in this Scottish abbey, the heart of Robert the Bruce was buried. Intensely dramatic is the double incident of its being carried toward Palestine by its valorous custodian, who, in battle with the Saracens, hurled the casket containing it at the foe, with the cry, “Forward, heart of Bruce, and Douglas shall follow thee.”

In the chancel are famous tombs of men whose glory the poet has celebrated. Here, traditionally, at least, is the sepulchre of Michael Scott, visited, according to Sir Walter’s lay, by the monk accompanying William of Deloraine. With torch in hand and feet unshod, the holy man led the knight.

It was “in havoc of feudal war,” when the widowed Lady, mistress of Branksome Hall, was called upon to decide whether her daughter Margaret should be her “foeman’s bride.” “Amid the armed train” she called to her side William of Deloraine and bade him visit the wizard’s tomb on St. Michael’s night and get from his dead hand, “the bead, scroll, or be it book,” to decide as to the marriage.

Now for Scott’s home! On the bank of Scotland’s most famous river, the Tweed, two miles above Melrose, was a small farm called Clarty Hole, which the great novelist bought in 1811. Changing the name to Abbotsford, he built a small villa, which is now the western wing of the present edifice. As he prospered, he made additions in the varied styles of his country’s architecture in different epochs. The result is a large and irregularly built mansion, which the “Wizard of the North” occupied twenty-one years. It has been called “a romance in stone and lime.” Knowing that the Tweed had been for centuries beaded like a rosary with monasteries and that monks had often crossed at the ford near by, Sir Walter coined the new name and gave it to the structure in which so much of his wonderful work was done for the delight of generations. Curiously enough, in America, while many places have been named after persons and events suggested by Scott’s fiction, only one town, and that in Wisconsin, bears this name of Abbotsford.

With a jolly party of Americans, we entered the house, thinking of Wolfert’s Roost at Tarrytown, New York, and its occupant Washington Irving, who had been a warm friend of Sir Walter. It was he who gave him, among other ideas, the original of Rebecca, a Jewish maiden of Philadelphia, whose idealization appears, in Scott’s beautiful story of “Ivanhoe,” as the daughter of Isaac of York. Memory also recalls that Scott wrote poetry that is yet sung in Christian worship, for in Rebecca’s mouth he puts the lyric,—

In the dim aisles of Melrose Abbey, before Michael Scott’s tomb, “the hymn of intercession rose.” The mediæval Latin of “Dies Iræ” has many stanzas, but Scott condensed their substance into twelve lines, beginning;—

We were shown the novelist’s study and his library, the drawing-room and the entrance hall. The roof of the library is designed chiefly from models taken from Roslyn Chapel, with its matchless pillar that suggests a casket of jewels. While many objects interested us both, it is clear, on the surface of things, that our lady companion, Quandril, was not so much concerned with what the cicerone told to the group of listeners as were certain male students present, who, also, were slaves of the pen: to wit, that when Sir Walter could not sleep, because of abnormal brain activity, he would come out of his bedroom, through the door, which was pointed out to us in the upper corner, and shave himself. This mechanical operation, with industry applied to brush, lather, steel, and stubble, diverted his attention and soothed his nerves. More than one brain-worker, imitating Sir Walter, has found that this remedy for insomnia is usually effectual.

Another fascinating monastic ruin is Dryburgh on the Tweed. It was once the scene of Druidical rites. The original name was Celtic, meaning the “bank of the oaks.” St. Modan, an Irish Culdee, established a sanctuary here in the sixth century, and King David I, in 1150, built the fine abbey. Here, in St. Mary’s aisle, sleeps the dust of the romancer who re-created, to the imagination, mediæval Scotland. Certainly her greatest interpreter in prose and verse is one of the land’s jewels and a material asset of permanent value.

The fame of Sir Walter yields a revenue, which, though not recorded in government documents, is worth to the Scottish people millions of guineas. From all over the world come annually tens of thousands of pilgrims to Scotland, and they journey hither because the “Wizard of the North” has magnetized them through his magic pen. Probably a majority are Americans. Not even Shakespeare can attract, to Stratford, at least, so many literary or otherwise interested pilgrims of the spirit, as does Burns or Scott.

We move next and still southward to Gretna Green—for centuries mentioned with jest and merriment. Of old, those rigid laws of State-Church-ridden England concerning marriage, which made the blood of Free Churchmen boil, while rousing the contempt and disgust of Americans, compelled many runaway couples from across the English border to seek legal union under the more easy statutes of Scotland. Gretna Green was the first convenient halting-place for those who would evade the oppressive requirements of the English Marriage Act. For generations, thousands of nuptial ceremonies were performed by various local persons or officials, though chiefly by the village blacksmith. Other places, like Lamberton, shared in the honors and revenue also. One sign, visible for many years, read, “Ginger Beer Sold Here, and marriages performed on the most reasonable terms.”

English law, framed by the House of Lords, compelled not only the consent of parents and guardians, but also the publication of banns, the presence of a priest of the Established Church, fixed and inconvenient hours, and other items of delay and expense. All that Scotland required, however, as in New York State, was a mutual declaration of marriage, to be exchanged in presence of witnesses.

The blacksmith of Gretna Green was no more important than other village characters, nor did his anvil and tongs have any ritual significance, because any witness was eligible to solemnize a ceremony which could be performed instantly. Gradually, however, as in so many other instances of original nonentities in Church and State, the blacksmith gradually assumed an authority which imposed upon the credulity of the English strangers, who usually came in a fluttering mood. In that way, the local disciple of St. Dunstan is said to have profited handsomely by the liberality usually dispensed on such felicitous occasions. The couple could then return at once to England, where their marriage was recognized as valid, because the nuptial union, if contracted according to the law of the place where the parties took the marital vow, was legal in the United Kingdom.

After the severity of the English law, under the hammering of the Free Church had been modified, Gretna Green was spoiled as a more or less romantic place of marriages, and held no charms for elopers. Scottish law, also, was so changed as to check this evasion of the English statutes. No irregular marriage of the kind, formerly and extensively in vogue, is now valid, unless one of the parties has lived in Scotland for twenty-one days before becoming either bride or groom. Gretna Green no longer points a joke or slur except in the preterite sense.

Sir Walter Scott, who sentinels for us the enchanted land we are entering, was in large measure the interpreter of Scotland, but he was more. In a sense, he was his native country’s epitome and incarnation. His literary career, however, illustrated, in miniature, almost all that Disraeli has written in his “Curiosities of Literature,” and especially in the chapter concerning “the calamities of authors.” Happily, however, Scott’s life was free from those quarrels to which men of letters are so prone, and of which American literary history is sufficiently full. Millions have been delighted with his poetry, which he continued to write until Byron, his rival, had occulted his fame. He is credited with having “invented the historical novel”—an award of honor with which, unless the claim is localized to Europe, those who are familiar with the literature of either China or Japan cannot possibly agree. Yet, in English, he was pioneer in making the facts of history seem more real through romance.

Scott was born in a happy time and in the right place—on the borderland, which for ages had been the domain of Mars. Here, in earlier days, the Roman and the Pict had striven for mastery. Later, Celtic Scot and invaders of Continental stock fought over and stained almost every acre with blood. Still later, the Lowlanders, of Teutonic origin, and the southern English battled with one another for centuries. On a soil strewn with mossy and ivied ruins, amid a landscape that had for him a thousand tongues, and in an air that was full of legend, song, and story, Scott grew up. Though not much of a routine student, he was a ravenous reader. Through his own neglect of mental discipline, in which under good teachers he might have perfected himself, he entered into active life, notably defective on the philosophic side of his mental equipment, and somewhat ill-balanced in his perspective of the past, while shallow in his views of contemporary life.

Despite Scott’s brilliant imagery, and the compelling charm of his pageants of history, there were never such Middle Ages as he pictured. For, while the lords and ladies, the heroes and the armed men, their exploits and adventures in castle, tourney, and field, are pictured in rapid movement and with fascinating color, yet of the real Middle Ages, which, for the mass of humanity, meant serfdom and slavery, with brutality and licentiousness above, weakness and ignorance below, with frequent visits of plague, pestilence, and famine, Scott has next to nothing to say. As for his anachronisms, their name is legion.

Nevertheless Scott had the supreme power of vitalizing character. He has enriched our experience, through imaginative contact with beings who are ever afterwards more intimately distinct and real for us than the people we daily meet. None could surpass and few equal Scott in clothing a historical fact or fossil with the pulsing blood and radiant bloom of life, compelling it to stand forth in resurrection of power. Scott thus surely possesses the final test of greatness, in his ability to impress our imagination, while haunting our minds with figures and events that seem to have life even more abundantly than mortal beings who are our neighbors.

Critics of to-day find fault with Scott, chiefly because he was deficient in certain of the higher and deeper qualities, for which they look in vain in his writings, while his poetry lacks those refinements of finish which we are accustomed to exact from our modern singers. However, those to whom the old problems of life and truth are yet unsettled, and who still discuss the questions over which men centuries ago fought and for which they were glad to spill their blood in defence and attack, accuse Scott of a partisanship which to them seems contemptible. Moreover, his many anachronisms and grave historical blunders, viewed in the light of a larger knowledge of men and nations, seem ridiculous.

Yet after all censure has been meted out and judgment given, it is probable that in frank abandon for boldness and breadth of effect, and in painting with words a succession of clear pictures, his poems are unexcelled in careless, rapid, easy narrative and in unfailing life, spirit, vigorous and fiery movement. Had Scott exercised over his prose writings a more jealous rigor of supervision, and had he eliminated the occasional infusions of obviously inferior matter, his entire body of writings would have been even more familiar and popular than they are to-day. It is safe to say that only a selection of the most notable of his works is really enjoyed in our age, though undoubtedly there will always be loyal lovers of the “Magician of the North,” who still loyally read through Scott’s entire repertoire. Indeed, we have known some who do this annually and delightedly. Taking his romances in chronological order, one may travel in the observation car of imagination through an enchanted land, having a background of history; while his poems surpass Baedeker, Black, or Murray as guide books to Melrose Abbey, through the Trossachs, to Ellen’s Isle, or along Teviot’s “silver tide.”

CHAPTER VI

RAMBLES ALONG THE BORDER

Where does the Scot’s Land begin and where end? To the latter half of the question, the answer is apparently easy, for the sea encloses the peninsula. Thus, on three sides, salt water forms the boundary, though many are the islands beyond. On the southern or land side, the region was for ages debatable and only in recent times fixed. Scotland’s scientific frontier is young.

Sixteen times did we cross this border-line, to see homes and native people as well as places. In some years we went swiftly over the steel rails by steam, in others tarried in town and country, and rambled over heath, hill, and moor, to see the face of the land. We lived again, in our saunterings, by the magic of imagination, in the past of history. Affluent is the lore to be enjoyed in exploring what was once the Debatable or No Man’s Land.

What area is richer in ruins than that of the shire counties bordering the two countries? Yet there is a difference, both in nature and art. On the English side, not a few relics in stone remain of the old days, both in picturesque ruins and in inhabited and modernized castles. On the other or Scotch side, few are the towers yet visible, while over the sites of what were once thick-walled places of defence and often the scene of blows and strife, the cattle now roam, the plough cuts its furrows, or only grassy mounds mark the spot where passions raged. Let us glance at this border region, its features, its names, and its chronology. How did “Scotland” “get on the map”?

This familiar name is comparatively modern, but Caledonia is ancient and poetical. The Roman poet Lucan, in A.D. 64, makes use of the term, and in Roman writers we find that there existed a district, a forest, and a tribe, each bearing the name “Caledonia,” and spoken of by Ptolemy. The first Latin invasion was under Agricola, about A.D. 83, and a decisive battle was fought, according to his son-in-law, Tacitus, on the slopes of Mons Graupius, a range of hills which in modern days is known as the “Grampian Hills.” To our childish imagination, “Norval” whose father fed his flock on these heathery heights, was more of a living hero than was the mighty Roman. Of Agricola’s wall, strengthened with a line of forts, there are remains still standing, and two of these strongholds, at Camelon and Barhill, have been identified and excavated.

Perhaps the most northerly of the ascertained Roman encampments in Scotland is at Inchtuthill. Where the Tay and Isla Rivers join their waters—

The Romans left the country and did not enter it again until A.D. 140, when the wall of Antoninus Pius was built, from sea to sea, and other forts erected. It was on pillared crags and prow-like headlands, between the North and South Tynes, along the verge of which the Romans carried their boundary of stone.

The Caledonians remained unconquered and regained full possession of their soil, about A.D. 180. Then the Emperor Septimus Severus invaded the land, but after his death the Roman writ never ran again north of the Cheviot Hills. Summing up the whole matter, the Latin occupation was military, without effect on Caledonian civilization, so that the people of this Celtic northland were left to work out their own evolution without Roman influence and under the ægis of Christianity.

If we may trust our old friend Lemprière (1765–1824), of Classical Dictionary fame,—the second edition of whose useful manual furnished, to a clerk in Albany, the Greek and Latin names which he shot, like grape and canister, over the “Military Tract,” in New York State, surveyed by Simeon DeWitt,—we may get light on the meaning of “Caledonia” and “Scot.” The former comes from “Kaled,” meaning “rough”; hence the “Caledonii,” “the rude nation,”—doubtless an opinion held mutually of one another by the Romans and their opponents. The term survives in the second syllable of Dunkeld. “Pict,” or “pecht,” is stated to mean “freebooters.” “Scot” means “allied,” or in “union,” and the Scots formed a united nation. Another author traces Caledonia to the term “Gael-doch,” meaning “the country of the Gael,” or the Highlander.

After the invasions of the Romans, there followed the Teutonic incursions and settlements, which were by the mediæval kingdoms, and the struggles between the Northerners and Southrons, but no regular boundary was recognized until 1532. For a millennium and a half, or from Roman times, this border land was a region given up to lawlessness, nor did anything approaching order seem possible until Christianity had been generally accepted. Faith transformed both society and the face of nature. By the twelfth century, churches, abbeys, and monasteries had made the rugged landscape smile in beauty, while softening somewhat the manners of the rude inhabitants. Yet even within times of written history, nine great battles and innumerable raids, of which several are notable in record, song, or ballad, took place in this region. These, for the most part, were either race struggles or contests for the supremacy of kings.

In modern days, when “the border,” though no longer a legal term, holds its place in history and literature, it has been common to speak of the country “north of the Tweed” as meaning Scotland. Yet this river forms fewer than twenty miles of the recognized boundary, which in a straight line would be but seventy miles, but which, following natural features of river, hill burn, moor, arm of the sea, and imaginary lines, measures one hundred and eight miles. The ridge of the Cheviot Hills is the main feature of demarcation for about twenty-five miles. A tributary of the Esk prolongs the line, and the Sark and the Solway Firth complete the frontier which divides the two lands. The English counties of Northumberland and Cumberland are thus separated from the Scottish shires of Berwick, Roxburghe, and Dumfries. In former times, “the frontier shifted according to the surging tides of war and diplomacy.”

Even to the eleventh century, the old Kingdom of Northumbria included part of what is now Scotland, up to the Firth of Forth and as far west as Stirling. In 1081, however, the Earl of Northumberland ceded the district which made the Tweed the southern boundary of the Kingdom of the Scots. Hence the honor of antiquity belonging to the Tweed as the eastern border-line! On the west, however, William the Conqueror wrenched Cumberland from the Scottish sceptre, and ever since it has remained in England.

For six hundred years, from the eleventh to near the end of the seventeenth century, war was the normal condition. Peace was only occasional. In this era were built hundreds of those three-storied square towers with turrets at the corners, of which so many ruins or overgrown sites remain. On each floor was one room, the lower one for cattle, the upper for the laird and his family, and a few ready-armed retainers. Around this bastel-house, or fortified dwelling, were ranged the thatched huts of the followers of the chief. These, on the signal of approaching enemies, or armed force, crowded into the stronghold. In feudal days, when these strong towers were like links in a chain, prompt and effective notice of approaching marauders could be sent many leagues by means of beacon fires kindled in the tower-tops and on the walls. Human existence in these abodes, during a prolonged siege, may be imagined.

Perhaps the best picture of castle and tower life in this era, though somewhat glorified, is that of Branksome Hall, in “The Lay of the Last Minstrel.” The nine and twenty knights, in full armor night and day, “drank the red wine through their helmets barred.” The glamour of Scott, the literary wizard, makes castle life seem almost enviable—but oh, the reality! Happily to-day lovely homes have taken the place of these ancient strongholds.

On the Scottish side, besides numerous small streams, are many stretches of fertile land with rich valleys and intervales, while much of the scenery is romantic and beautiful. In the southwestern corner, one does not forget that from the eighth to the twelfth century flourished the Kingdom of Strathclyde, which bordered on the Clyde River. In the Rhins of Galloway is the parish of Kirkmaiden, which is Scotland’s most southern point. The common, local expression, “from Maidenkirk to John o’ Groat’s House,” is like that of “from Dan to Beersheba.” Now, however, not a few sites famous in song and story and once part of the Scots’ land are in England, notably, Flodden Field, and in the sea, Lindisfarne, or Holy Isle, so famous in “Marmion.” To-day, on Holy Isle, the summer tourists make merry and few perhaps think of the story of Constance the nun, betrayed by Marmion the knight, condemned by her superior, incarcerated in the dungeons, and sent to her death.

Probably the ages to come will show us that the most enduring monuments of centuries of strife, in this borderland, must not be looked for in its memorials of stone, but in language. The “winged words” may outlast what, because of material solidity, was meant for permanence and strength. Minstrelsy and ballad, poem and song, keep alive the acts of courage and the gallantry of the men and the sacrifice and devotion of the women which light up these dark centuries. To Scott, Billings, and Percy we owe a debt of gratitude, for rescuing from oblivion the gems of poet and harpist.