Belgian Fairy Tales

William Elliot Griffis

BOOKS BY

WILLIAM ELLIOT GRIFFIS

BELGIAN FAIRY TALES

Just such a book that the youngster will enjoy.

DUTCH FAIRY TALES

“A sheaf of delightful fairy stories from Holland, which abounds in legend and child-lore.”

THE FIRE-FLY’S LOVERS; and Other Fairy Tales of Old Japan

THE UNMANNERLY TIGER; and Other Korean Stories

Each volume 8vo. cloth. Illustrated in color.

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

New York

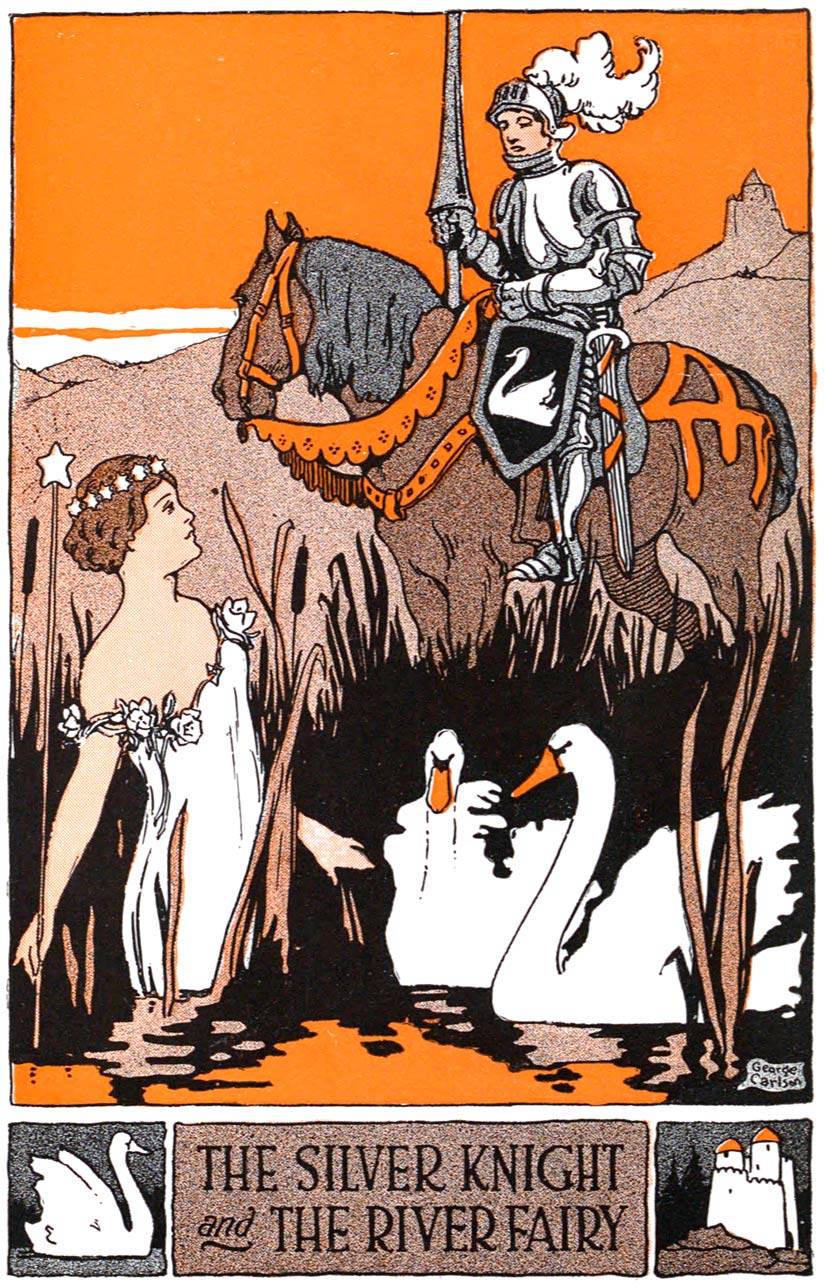

The Silver Knight and the River Fairy

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1919, by

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

TO

KATHARINE AND ELLIOT

TEDDY AND MICKEY

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |||||||

| I. | A Story for a Preface | 1 | ||||||

| II. | The War Storm and Baldy the Horse | 10 | ||||||

| III. | The Swan Maidens and the Silver Knight | 17 | ||||||

| IV. | A Congress of Belgian Fairies | 31 | ||||||

| V. | The Ogre in the Forest of Hazel Nuts | 44 | ||||||

| VI. | The Fairy of the Poppies | 56 | ||||||

| VII. | The Story of the Fleur-de-Lys | 65 | ||||||

| VIII. | The Irish Princess and Her Ship of Sod | 72 | ||||||

| IX. | Wine-Crust, the Blue-Beard of Flanders | 82 | ||||||

| X. | Lyderic, the Orphan | 92 | ||||||

| XI. | The Long Wappers, and Their Tricks | 101 | ||||||

| XII. | The Pilgrim Pigeons | 110 | ||||||

| XIII. | The Fairy Queen and the Carrier Doves | 121 | ||||||

| XIV. | The Far Famed Oriental | 130 | ||||||

| XV. | Puss Geiko and Her Travels | 140 | ||||||

| XVI. | The Marriage of the Fairies | 150 | ||||||

| XVII. | The Enchanted Windmill | 159 | ||||||

| XVIII. | Turk, Turban, Tulip and Dragon | 166 | ||||||

| XIX. | Up and Down and Up Again | 178 | ||||||

| XX. | The Golden Dragon of the Boringue | 188 | ||||||

| XXI. | The Red Caps and the Hunters | 199 | ||||||

| XXII. | The Split Tailed Lion | 208 | ||||||

| XXIII. | Rinaldo and His Wonderful Horse Bayard | 215 | ||||||

| XXIV. | The Belgian Bunny | 225 | ||||||

| XXV. | The Fairies of the Kitchen | 235 | ||||||

| XXVI. | A Society to Make Fairy Tales Come True | 245 | ||||||

[1]

Belgian Fairy Tales

I

A STORY FOR A PREFACE

(Which Tells of the People, Scenery and Animals in Belgium)

The name which the Belgians give to their country is Belgique. The English form Belgium is that from the Latin of ancient days.

The country is inhabited by two races. Draw a line across the map of Belgium and you divide the kingdom into two regions, inhabited by Flemings and Walloons.

Let the line pass from east and west through Brussels. North of this, as a rule, there are farms, gardens and sea coast. Here the people speak old Dutch, or Flemish, and most of them are fishermen, farmers, seaport men and traders. South of this line are mines, factories, furnaces, or flax fields and their talk is French. They are [2]called Walloons, which is only another way of pronouncing Gaul-loons. When Cæsar met and fought with their ancestors, whom he called the Belgii, he declared them “the bravest of all.”

We Americans ought to know who the Walloons are; for, in 1624, some of these people—even before the Dutch mothers and fathers, boys and girls came—settled New York and New Jersey. It was they who introduced on our soil the marguerite, or white-and-yellow daisy, and they were the first farmers in the Middle States. Moreover, when New Netherland received a civil government, it was named Nova Belgica, or New Belgium.

The finest part of Walloon Belgium is the hill country of the Ardennes. Here lived, in 1912, a boy named Emile, seventeen years old. His home was in one of those stone houses, which are common in the highlands of southern Belgium. All around him grew pine and birch trees, which made his part of the country look so different from the lowlands around Antwerp, where the tall, stiff poplars and the low branched willows abound. The one tree points its boughs up to the sky and the other down to the ground.

Emile’s father was a farmer, but the land of the hill country was not rich, because it was too full of rocks and stones. The soil was quite different from that down on the flax meadows, [3]towards France, and the flower gardens and truck farms of Flanders. Emile’s father could make more money by raising horses, for the pasture was rich and splendid horses they were, so big and strong.

The buyers, from the horse markets over in Germany, came every year into the Ardennes forest country, for they liked nothing better than to get these horses for the Kaiser’s artillery regiments. For, although the animals of this breed were not as big and heavy as the Flemish cart horses, they were not so slow and clumsy. In fact, there were few places in Europe, where the horses excelled, in their power to gallop while harnessed to heavy loads. They had what jockies call good “wind” and “bottom,” that is, staying power, stamina, grit, or what we call, in boys and men, “pep.” Emile, with his father, learned to take good care of the mares and kept them in fine condition with brush and curry comb, until their coats were glossy. One day, an unusually fine colt was born, just before Christmas of 1909.

“What shall we name it?” asked the father of his wife; for it was her favorite mare. She drove it to church every Sunday, and when born Emile’s mother had named it “Jacqueline,” after the famous medieval princess.

Now, it was a day or two after King Leopold had died, ending a long reign of forty-four years, [4]and the present King Albert had become ruler of the Belgic country. Yet he did not call himself “sovereign,” or “autocrat,” like a Czar, or “emperor,” as the German Wilhelm did, but “king of the Belgians.” That is, he wished to treat his fellow countrymen not as subjects, but as gentlemen like himself. So, when he issued a proclamation, he addressed them, not as inferiors, but as “Messieurs,” that is, gentlemen.

Emile’s mother who had, years before, lost one of her baby boys, answered:

“Our dead ruler will have a great monument, but for Baldwin, his son, who was to have been king, instead of Albert, but died early, there will be few to remember him: So let us call our new colt ‘Baldwin’ and let it be Emile’s own—his pet always.”

“Good,” said the father, and Baldwin it was, or “Baldy,” for short; and the pretty young horse was given to Emile for his very own.

“It’s yours to play with, and to work for you, all your life,” said papa Henri, “but you must care for it, as your mother and I have cared for you.”

“That I will, father. You may trust me,” answered the boy.

As soon as the new long-legged stranger was able to cease taking refreshments from its mother, Emile fed the colt out of his hand. After Sunday [5]dinner, he would go out into the garden, pluck some tops or leaves of tender plants, such as radishes, peas, or the like, hiding a lump of beet sugar under the greens. Then he would follow the path to the stable to give a treat to both mother and son. Both the old mare and young Baldy seemed to have an almost human look of gratitude, when they cast their eyes on their owners and good friends. Nevertheless, no horse ever yet learned to talk with its tail and say “thank you,” like a dog.

When the time came to break Baldy to harness and for farm work, the well fed and kindly animal proved to be one of the strongest and best. It seemed equal to most horses of at least six years of age.

But it was not always sugar and young carrot tops, for Baldy! Emile usually gave it salt out of his own hand. Sometimes he loved to play a joke and even to tantalize his pet, though for a minute or two, only. When out at pasture, and its master wanted to throw the halter over its neck, Baldy would give Emile tit for tat and had his horse-fun by cantering off. Then Emile would gather up the heads of white clover and holding these, down deep in the palm of his hand, would entice Baldy near, as if it were salt. Then he would throw the halter over his neck, and Baldy was a prisoner. Emile took care not to [6]play this trick too often, and sometimes gave his pet real salt, even when out in the field. If horses could smile, Baldy would have laughed out loud.

There were other pets in Emile’s home, besides the colt; and, first of all, his dog Goldspur, named after the trophies found on the field of Courtrai, when the Flemish weavers, with their pikes, beat the French knights, in 1302. Though he worked hard all day, outdoors on the farm in summer, and tended the cows and horses in winter, he had plenty of time to give to his hares, which were so big and fat, that they took the prize at the local fair. In his loft over the barn, he had a dozen or two carrier pigeons. Some of these had been hatched on his father’s farm, but most of them had been brought from Ghent, a city down on the plain, where the two rivers, the Lys and the Scheldt join. Here, where there were plenty of canals, he had a cousin Rogier, a boy of his own age. The two lads often sent messages to each other by their winged letter carriers.

The Walloon folk pronounced the name of this city of Ghent, or Gand, in the French way, which sounds a good deal like “gong”; while the Flemings, who talk Dutch, say it with a hard g, and as if “gent.” We Americans put an h in the name; for fear, I suppose, lest we should pronounce it like “gent” in gentleman. [7]

In fact, when you get into Belgium, you find that even the laws and some of the newspapers, as well as names of places, have two forms, French or Walloon, and Dutch or Flemish. The British soldiers usually take no further trouble to pronounce foreign names, except as they are spelled at home, on their island. That is the reason why, for the name of Ypres, around which the war raged during four years, one may hear the sounds—French, eepe, or epray; Flemish, i-per; and, what the English Tommies say, “wipers.”

Not long after his nineteenth birthday, Emile sent to his cousin Rogier, at Ghent, a message. It was written on a note sheet, as light as tissue paper. Rolled inside a bit of tin foil, in case of rain, and with black sewing silk from his mother’s work basket, it was tied on the pigeon’s right leg, between its pink toes and the first joint of the knee. Safely making the journey, the bird fluttered down on Rogier’s dove cote, which was set on a post in his garden. Untying the missive very gently, and letting the bird into the cote to rest, Rogier read:

Dear Cousin:

“Crops were poor this year, and father had to sell my pet horse, Baldwin. I took it hard, and almost cried, to see a German horse dealer pay [8]down the money and lead it off. When out in the road, Baldy actually turned round and looked back at us. The very next day, word came from the army headquarters that I must report to camp at Ypres. From next week, Tuesday, I shall be a soldier under the black, yellow and red flag. Hurrah! Sister Yvette has been singing the ‘Brabançonne,’ when she isn’t crying. I have only one sister, you know. I hope they’ll put me in the cavalry; or, if not, assign me to the machine-gun battalion. Goodbye! We’ll meet, when I get down into Flanders.”

All too soon, the looming shadow, cast from the east, shortened and the war-storm broke. On Sunday night, August 2, 1914, Germany sent an ultimatum, demanding passage of her armies through Belgium to France. To the Kaiser, Belgium was no more than a turnpike road to Paris. The hero, King Albert, knowing he had his people behind him, refused to cringe and become a German slave. It was like the boy David defying the giant Philistine. The national flag—black, yellow and red—the ancient colors of Brabant, the central province in the kingdom of the nine that made Belgium a nation—was unfurled everywhere by “men determined to be free.” That is what our Anthony Wayne said at Stony Point, in 1779. [9]

By this time, in 1914, Emile was a seasoned soldier, not in the saddle, as he had hoped at first, but with the dog-drawn mitrailleuse, or machine-gun battalion, No. 40. A happy soldier he was, ready to fight “for King, for Law, for Liberty”—as the chorus in the Brabançonne—the national anthem—declared. Still happier was he to have with him in harness, drawing the revolving, quick-firing cannon, of which he was sergeant pointer, his pet dog, Goldspur. Like man, like dog was the Belgian War Department’s acceptance of both—“in the first class of efficiency.”

This was Belgium at peace, under her beloved King Albert and Queen Margaret. Rich in wonders of art and architecture, in fairy, folk wonder and hero lore, in traditions of valor and industry. When, again and again, the story teller visited the country, he brought back, each time, the seed, for flowers, in the bed-time story-garden. [10]

II

THE WAR STORM AND BALDY THE HORSE

War, in modern times, comes like a lightning flash. Seven thousand German automobiles, loaded with soldiers, rushed over the Belgian border. The Uhlans galloped in by other wagon roads, and twenty army corps, in swift trains, followed. Belgium was desolated by fire and sword. The Liège forts, once thought impregnable, were reduced to rubbish. Louvain was given to the flames.

What awful odds! Only 68,000 men of all arms, in the Belgian Service, to stand against the onrush of hordes! Yet they did. Day by day, the Belgians wondered! Where were the Allies, that had promised to help them? Where were the red coats, or the khaki of the English, or the kilts of the Scotch, or the “invisible blue” of the French poilus? Had any one heard a sound of the bagpipes?

During those six weeks, before the British guns fired a shot, or the French sent reinforcements, the Belgian soldiers fought on, contesting [11]the possession of their native soil, inch by inch. Many a time the machine-gun batteries drove off the German Uhlans and destroyed both the gunners and horses of their batteries; each time retreating in order and safety, though many a comrade of Emile’s was missing. City after city fell, until Brussels was occupied. It was thought that Antwerp could be saved, though the garrison was very small. Some English marines had come to help; and more, yes, a big army, was coming. So every one said.

So Emile and the other gunners braced up. They were again full of courage, when ordered to defend a narrow road, which was really a dyke, or causeway, with mud fields on either side, but commanding the main road, over which the German artillery must come. Here, with what military men call an enfilading fire, they could open on the Germans. They were given this post the night before, with only haversack rations.

The next morning, when breakfast, and a cold one, was hardly over, and the dogs had been drawn out of the shafts and sent to the rear, the German train of guns was heard in the distance thundering towards them. The Huns must go straight ahead; for, on either side of the brick paved road, were the ditches and destruction.

“’Twill be a hot fight, but keep cool, gentlemen,” [12]cried the officer in command, “then, at the right moment, let every shot tell.”

“Crack, crack, crack!” The machine-guns opened and sheets of lead and fire swept a wide area. Bullets, not by hundreds but thousands, were showered upon horses, men, caissons and guns. Within five minutes, half of that German battery was a wreck. The dead horses and men, of the three forward cannon of the six, were piled on top of each other, or were rolling and plunging over the dyke. The others behind had to halt.

Emile noticed that one of the horses, from the German battery, drawing the front gun had been stung by a ball that scraped his flank. Part of the wooden tongue and whiffle tree had been shot away. They were dangling behind him, as he dashed madly forward.

This horse was no other than Baldy. Instantly recognizing his old pet, Emile waved his hand to the gunners of his company to spare the animal. He ran forward, shouting “Baldy, Baldy.”

The horse stopped and sniffed the air; but at the strange uniform, halted, even while he cocked his ear, awaiting further developments. Emile took in the situation at once, for he too had “horse sense.” Jumping down along the grassy sides of the dyke, he picked off enough [13]white flowers to stick between his fingers and in his palm, so as to look like salt. Then in Walloon talk, he tried his old trick of enticing Baldy. As if in front of a phonograph, this four legged creature that had, for years, heard only German words, for “halt” or “back” or “get up,” moved his head sideways, first to the right, then up to the left, then down, as if pondering. At last, throwing back his head he neighed joyfully and trotted forward, as if he surely recognized his old master, who now patted him as if he welcomed a human friend.

It was a family reunion, for Emile, leading his prize back, amid his admiring companions, quickly told his story in brief to his captain, who bade him to lead Baldy over to Goldspur. There was no time to unharness the dog, nor any need of doing it; for as soon as Baldy was near enough, the dog’s tongue was as active as his tail. While one end of the animal was busy in licking the horse’s muzzle, as in old friendship, the other terminal was wig-wagging, as if a sailor boy were signalling “I’m glad to see you.”

It was many minutes before the Germans, further back, could unlimber a gun on the narrow road, point it at the Belgians and send shrapnel among them. By this time, however, the machine-gunners had made good their retreat, according to orders. The dogs pulled off the [14]light Belgian artillery and the whole army moved to the defence of Antwerp. Emile’s battalion was soon out of range of the enemy, who wasted his shells in vain.

It would be a sad story to tell in detail of the fall of Antwerp. Against the overwhelming numbers, with few or no allies to help, and the heavy siege guns of the Huns in activity, day and night, the Belgians were no match for their foes, and the Germans entered the city.

Two mighty heroes rose out of the Belgian commonwealth during this awful, desolating war. One was that of Cardinal Mercier—bravest of the brave. The other was King Albert. He lived up to his colors, for in the Belgian flag, the king’s color is black, standing for constancy, wisdom and prudence. Later, when the Americans had reached Belgium, Albert rode with his queen, Margaret, into Ghent and Brussels.

What happened later, to Emile, and Baldy, and Goldspur, is told in his letter, from Queen Wilhelmina’s dominions, to his boy friend in Ghent.

“We are interned in a large camp in Gelderland, with British marines and sailors in one part and the Belgian army men in another. Baldy is rented out to a Dutch farmer near Nijkerk, till the war is over. The Dutch commandant lets me have Goldspur, and being our mascot, [15]is a great favorite with all the men. A prisoner’s life is dull and tiresome, and we can only wait for victory, which must surely come. Queen Wilhelmina’s government has cared for a quarter of a million of our Belgian civilians and Holland spends one fifth of all her revenue in feeding them. Our people are building a splendid memorial of gratitude, at Amersfoort, and I am glad of it. One of our boys got hold of the words and music of an American song, and now the whole camp has learned to sing ‘The Yanks are coming,’ and I believe they’ll come, even beyond the Rhine.”

And they came, and of the three sons of the story-teller (who was himself one of Lincoln’s and Grant’s soldiers, a veteran of ’63), one was there; and to his grand children, these Belgian tales—mostly of the kind that have fairies in them—were first told. In these “Belgian Fairy” and wonder tales, we shall learn about the colors of the flag, and the national motto, and other things that, it is hoped, will make us Americans love Belgium the more, and all of us, at some time, see the country itself.

The little folks in wooden shoes have not forgotten how the American children sent to them a ship load of Christmas presents. Nor should we fail to remember that Belgium is one of our fatherlands, whence came the people who made [16]the first homes in the four Middle States. The first white children, born in New York State, were of Belgian parents.

Not all the stories in this book are fairy tales, but all tell of wonderful flowers, animals, inventions, people, things, and happenings, if not of dragons, ogres and lovely little fairy folks, who do astonishing things. In Belgium, neither fairies nor men are anything but industrious, so the fairies work hard always.

This is our preface. [17]

III

THE SWAN MAIDENS AND THE SILVER KNIGHT

The two countries, Gelderland and Brabant adjoin each other, but their rivers flow far apart.

Once there was a castle, that stood on the banks of the Scheldt, on which the city of Brabo, named Antwerp, stands. Instead of being full of light and joy for all within its walls, there was a princess named Elsje, who was kept a prisoner there.

Her father and mother, dying when she was a little child, left her in the care of a count, who was to be her guardian. This nobleman was a selfish villain, and hoped to get her lands and estate. So he shut her up as a prisoner in the castle. If any knight should fight and overcome him, the princess would be delivered; but, as the wicked count was a man of gigantic strength and skilled in war, no one had ever attempted to meet him in battle.

The Princess Elsje was very lovely in character. In her captivity she was kind to the birds [18]and all the winged creatures, being especially fond of seven swans, which she fed every day. Each one was very tame and took its food out of her hand. She knew them all by the names she had given them, Fuzzy, Buzzy, Trumpet, Jet, Diamond, Whitey and Black Eye. They were her best friends, for she was very lonely and had no human companions. Nor had she any idea that they were anything but dumb creatures that never could repay her kindness. But, strange to say, these seven swans were birds only in form. They had been changed by a wicked fairy from pretty maidens into swans. It was on this wise.

Once, while the good king of Gelderland had gone out hunting in the forest, with his lords and retainers, he rode in advance, for he was pursuing a deer. He got so far from his companions that he lost his way. Coming near a hut in the woods, to inquire how he might get back to his palace, he met an old woman. She promised to show him the way out and back home. Immediately the king pulled out his purse to hand her a gold coin; but the old woman proudly waved her hand to scorn the money and said to him, “You must marry my daughter and make her your queen. If you do not, you can never get home again.”

The king hesitated about giving his promise [19]at once, even before he had seen the lady, for he had seven motherless children, all daughters at home. Their mother, on her dying bed, had made her husband give her a promise that the children should always be first in his thoughts.

Now, if he should marry again, would his new wife be good to them? He would much rather that they should first see their future mother and give their love to her, before he took his second wife.

But now, as he was very weary and almost ready to drop with hunger, he could not hesitate. He might die of weakness, while vainly wandering in the forest. Moreover, the old woman said to him, quite sharply:

“If you refuse, you will never get out of these woods and will starve to death. Come into my hut and I will feed you well.”

The king entered and found sitting by the fire a most beautiful maiden. He thought he had never seen a woman so fair, yet he did not like her.

She rose from her seat and came forward to greet him, as if she had been waiting for him. There was a table spread with plenty of good things to eat. The king sat down and the damsel herself waited upon him while he enjoyed the meal.

But all the time, the king did not like her [20]looks, any more than at the first. At times he shuddered, for fear she might be some evil creature in lovely human form. However, he had promised the old woman to marry her daughter and it was now death to refuse. So he took the beautiful girl on his steed and rode straight to his castle, for the horse seemed to know the right way.

That very evening, the wedding took place with great pomp. The wonderful thing was, that all the lords and ladies and servants had supposed that their master the king had purposely left them, the day before, to make a journey to get him a wife. So they were now all ready for him in their best dresses and jewels, and glad to welcome his bride. All remarked upon her beauty, but the king still feared that his new wife was wicked and cruel, and his heart sank within him.

So, to make sure, he took his seven children off into a castle that was deep in the forests and not easily found. Even he himself had trouble in getting to it, until a wise old woman gave him a ball of yarn. This ball had the wonderful property of finding paths in the wood. If one threw it on the ground it would unroll of itself. So the king had a clue to the forest palace and daily went to visit his little folks and played with them. [21]

The new wife noticed his going away so often, and becoming jealous of her lord’s absences, she scolded him, saying to him that he did not love her, to be thus away from her so many times. At last she found out, from the palace servants, where he kept the ball.

Then she made seven little coats and in each one she sewed an evil charm, which her wicked old mother had taught her. Walking in the woods until she came to the castle, she pretended to be glad to see the children, telling them that she had brought each one a present. The little folks were delighted and thought their step-mother was both lovely and kind. They put on their new coats and then gleefully danced together, joining hands as in a chorus. But in a few minutes a strange feeling came over them. Wings grew where their arms had been, their necks lengthened, while their legs shortened and became weblike. They were all changed into swans and flew out of the window. So the king never saw his children again.

The seven swans enjoyed their life in the air and soon joined the great flock that belonged to the king of the country of Brabant, where the princess Elsje was kept in the castle, on the Scheldt River. The royal swanherd, though he had a thousand or more birds under his care, when counting the cygnets, or swan babies, noticed [22]the addition of the seven pretty birds and wondered whence they had come.

The seven swan maidens soon got acquainted with all the other swans, for these birds are very sociable and talk to each other in their own language. In this way they learned the story of the captive Brabant princess. When they found they were her favorites, and she had given each one of them a name, and every day called them to be fed, their hearts were melted by the kindness of the pretty lady. Sometimes they found her in tears and heard her pray for wings to fly away. This made them wish that they could leave their swan forms and be like her again, as they once were. Or, if not thus able, they longed to help her in some way.

They all agreed that they would rather remain swan maidens and be free to fly and do as they liked, rising about and up into the air, or sailing on the water, than to be shut up for life in a prison. Even though it were in a castle with gardens and a swan lake, they would rather be birds than captives. They were filled with pity for the lonely princess thus pining away.

The oldest and the youngest of the seven swans, Fuzzy and Black Eye, both of which had snow white plumage, were especially eager to help the maiden. Of all the seven, they two were the strongest. Every day they declared [23]to their sisters and to the real swans that they would sometime find a way to set the princess free. The oldest of the swans only jeered at the idea or hissed scornfully.

“How can human beings fly? They have no wings like us and you boasters cannot give her yours.” And they laughed a swan’s laugh.

Now in one thing, at least, these seven swan sisters were different from the other birds. They were accustomed, every week or so, to make a long flight back to Gelderland, to their old forest home and playground, to take a look at their fond father, who, however, never dreamed that these winged creatures were his children.

In the times of these visits to the forest palace, but only while they were there, the enchantment failed; yet only for a quarter of an hour. During these few minutes, while in the woods, they played together as girls, as in the happy days of yore, when their father used to come and see them. But this they could not do now within the royal palace gardens, where their father walked, and when in the dense forest itself, they could not find the way out as girls, for they were swans again, almost as soon as they started to find the path.

So they did the next best thing. They flew to the royal palace gardens and circled around his head and dropped feathers to show their [24]feelings. The king noticed this, and gave strict orders that no one should shoot an arrow, throw a net, or lay a trap for these birds, that he loved to welcome as visitors which gave him happiness. The wicked queen, however, knew all about these swans, but she never told her husband. She let him mourn for his children, month after month and year after year.

Now while the swan sisters were thinking of rescuing the Princess Elsje, she also was planning to save them, in order to bring them back to human form. There was a good fairy who lived on the Lek River, who hated the wicked step-mother of the swan maidens and knew how to destroy her enchantments. But this good fairy possessed her power only on the water, but she fastened on the neck of Fuzzy, the oldest of the swans, a message telling the princess how to break the charm.

The way to do it was this: The princess was to make seven little coats of swan feathers, and then she was not to speak a word to any soul, for seven months. At the end of that time, she was to put a coat on each of the swan sisters. Then, they would at once become maidens again.

Now in Gelderland there lived a handsome young knight, who wore a suit of armor of silver steel and had a plume of snow white feathers in his helmet. He was as brave as a lion and [25]loved to rescue poor people from robbers and to help all who were in trouble.

One day, while out hunting, he by chance reached the castle in the woods, where the king had kept his children and to which the seven swans flew every week. He drew his bow and was just about to shoot, when the birds dropped their feather suits and seven pretty maidens stood before him.

“Oh, good sir, hurt us not,” they cried, “we are human, only for a quarter of an hour; but, oh, do come and follow us. We’ll guide you to a princess in distress and you can save her.”

The knight was delighted to hear these words, for the task the swan maidens proposed was just what he longed to attempt. They had hardly told their story, before they had to resume their swan forms. It was agreed that Fuzzy and Black Eye, the whitest and the strongest of the seven swans, should be the pilots of the knight to the well-guarded castle, where the princess was a captive. The five swans flew back to the flock, but the absence of the other two was not noticed by the king’s swanherd.

So, guided by his brace of snowy white and feathered pilots, who kept in the air above him, the knight made his way through the forests and across the country, until he came to the Scheldt River. There were no boats, the current was [26]rapid and the river wide. How should he get across?

“Oh, how shall we help our knight down such a flood as this?” said Fuzzy to Black Eye.

While the Silver Knight was wondering, the good fairy who had sent the message to the princess, stepped out from among the river weeds. She had a star crown on her head and a wand of gold in her hand. She spoke thus to the knight:

“Take that dead tree trunk, which lies on the ground, all wreathed with vines, and launch it into the river, for my power extends only over the water. Because of your knightly record as a brave hero, I shall have these swans guide you to the castle. Once on shore, you must fight your own battle. Promise to rescue the princess.”

The knight took oath, on the hilt of his sword, that he would. Then the fairy touched the dead tree and it became a pretty boat, shaped like a shell. She bade the two swans take their places in front. Then touching the wild vines, growing on the log, and throwing them over their long curved snow-white necks, lo! they became silver harness, to draw the boat, and silver bridles, which the rider standing in the boat, held, as the birds darted swiftly forward.

He waved his thanks and farewell in gratitude to the fairy. [27]

“Good speed and sure success to you,” cried the fairy. “You will find the princess doing my work.”

It was to be a battle of enchantments, for the good fairy was trying to undo the spell, which the wicked stepmother, the king’s wife, had cast over the swan maidens. Yet she could do nothing on land without the aid of a brave knight. She had been a long time waiting for such a hero. Now he had come.

To make effective the charm of restoring swan maidens to human forms, while she was making the feather coats, it was absolutely necessary for the Princess Elsje to do two hard things; one was, not to speak a word till the coats were finished, and the swans transformed; the second was not to ask the knight who he was or where he came from. Even when he was her husband, she must be silent on this matter. She had to promise this, or the good fairy would do nothing.

Into the swan boat, the young knight in his shining silver-steel armor, bravely stepped. Then with their four web feet beating tirelessly under the river waves, that curled against their breasts, the two strong birds drew the shell boat until they were near the castle in Brabant.

It was a day of tournament, and hundreds of lords and ladies were gathered together to see the knights on horseback rush at each other in [28]the game of friendly rivalry, as rough as war, in which sometimes men were killed. The herald sounded the trumpet to call forth a champion for the imprisoned maiden. Whosoever should vanquish the cruel count should have the lady’s strong castle and her rich estate. Glorious in her beauty, Princess Elsje sat in the place of honor, crowned with flowers, as she had sat again and again before, but never a word had she spoken to a soul.

The echoes of the first trumpet blast died away. No one came.

The second summons sounded. None answered.

The third blast had not ended, before the knight in the silver steel armor stepped forward. He asked the maiden if she would accept him as her husband, if he overcame the count. She spoke not a word, but nodded her head, beaming with a joy that inspired him to valor.

The Silver Knight threw down his glove as a challenge.

Again the trumpet pealed and the two champions rushed at each other. All expected that the count, being so heavy and strong would win, but the battle was soon decided, for the Silver Knight was victorious. The count, senseless, and with a broken head, was borne off the field.

Now the knight had been told not to expect [29]his bride to speak to him until after the marriage, but to be content with a nod of her head and the language of her eyes. Yet those eyes spoke to him their message, and he was full of joy.

Even when he asked her whether she would marry him, without ever now, or hereafter, asking who he was, or whence he came, her answer was with a nod of the head, and a low bow, with one of her hands on her heart and the other raised to heaven. This was enough. He was satisfied.

The wedding was celebrated with great pomp and joy. For many weeks afterwards, the silent princess kept busy with her needle, making little coats of swan feathers, but of this her husband seemed to approve and gladly he praised his bride’s industry.

Now on the day when the seven swans from Gelderland were accustomed to fly back to their old home, the forest castle, and before they had risen from the water to stretch their wings, the princess called them, and each by name before her. Then, in the presence of her knight, she threw the coats over them. Instantly feathers, wings, arched necks and webbed feet disappeared, and seven lovely maidens stood before them. Now, since their father had died, they all asked to stay in Brabant and serve the princess [30]at her court. This offer she gladly accepted.

But the princess had no sooner regained the use of her voice than she seemed consumed with a curiosity she had not felt before. In the new joy of having fulfilled one promise, made to the river fairy in behalf of the swan sisters, she forgot that made to the knight, her husband. Her eagerness to know who and whence he was increased, until one day she burst out, with the questions. The knight reminded her of her vow which, with solemn gesture, she had made to him, before he risked his life for her. When she urged that his love for her could not be deep or real, if he kept a secret from her, he made answer:

“It is not I that love less, or have broken faith. It is you.” Then, rushing out of the palace, he leaped upon his horse and disappeared in the forest, riding back to Gelderland, and the princess though no longer a captive, but free and rich, was sorrowful and lonely. [31]

IV

A CONGRESS OF BELGIAN FAIRIES

There was great excitement in the Belgic fairyland at the wonderful things that men were doing in the world. The new inventions for flying, diving, racing, and what not, were upsetting all the old ideas as to what fairies alone could do.

It used to be that only fairies could fly in the air, like birds, or go far down beneath the waves and stay there, or travel under water, or move about near the bottom, like fishes.

In old times, it was only the elves, or gnomes, or kabouters, or it might be, dragons, that could find out and possess all the treasures that were inside the earth.

Only the fairies of long ago could rush along like the wind, anywhere, or carry messages as fast as lightning, but now men were doing these very things, for they could cross continents and oceans.

“We’ll hear of their landing in the moon, next,” said one vixen of a fairy, who did not like men.

“By and bye, we fairies won’t have anything to do,” said another. [32]

“If men keep on in this way,” remarked a third, “the children will not believe in us any more. Then we shall be banished entirely from the nursery and the picture books, and our friends, the artists and story-tellers, will lose their jobs.”

“It is just too horrible to think of,” said one of the oldest of the fairies, “but what are we going to do about it? Why, think of it, only last week they crossed the Atlantic, by speeding through the air. Before this, they made a voyage over the same mighty water by going down below the surface.”

“True, but I know the reason of all this,” said a wise, motherly looking fairy.

“Do tell us the reason and all about it,” cried out several young fairies in one breath.

“Well, I do not wonder at what they have been able to do; for long ago, they caught some of our smartest fairies, harnessed them and made beasts of burden of them, to do their work.”

“They lengthen their own life to shorten ours, that’s what they do,” said the fairy, who was very wise, but did not always have a sweet temper.

“How, what do you mean?” asked a couple of young fairies, that looked forward to an old age of about two million years.

“I mean what I have just said. These men [33]are like kidnappers, who first steal children and then give them other names, or alter their appearance. They change their dress, or clip their hair, and even mar their faces. They make them look so different, that even their own mothers, if they ever saw them again would not know them.”

“For instance? Give us an example,” challenged one incredulous, matter-of-fact fairy, who was inclined to take the men’s part.

“I will,” said the old fairy. “We used to have among our number a very strong fairy, called Stoom. Now, in his freedom, he used to do as he pleased. He blew things up whenever he felt like having a little fun, and he made a great fuss when affairs did not suit him. But, by and bye, the men caught him and put him inside of their boilers and pipes. They made stopcocks and gauges, pistons and valves, and all the things that are like the bits, and bridles, and traces, in which they harness horses. Now that they have got him well hitched, they make him work all day and often all night. He has to drive ships and engines, motors and plows, cars and wagons, and inventions and machinery of all sorts. They use him for pumping, hoisting, pounding, lighting, heating, and no one knows what. A windmill or a waterfall nowadays has no chance of competition with him.

“They call him Steam now. At any rate, he [34]is no longer one of us, for men have caught and tamed him. They have all sorts of gauges, meters, dials, regulators, and whatever will keep the poor fellow from blowing things up; for, they can tell at once the state of his temper. He cannot do as he pleases any more.”

“Well, they won’t catch me, I can tell you,” said one big fellow of a fairy, whose name, in Flemish, is frightful, but in English is ‘Perpetual Motion.’ “These men have been after me, for a thousand years and I call them fools; but, just when one thinks he has me, I give him the slip, and this every time. As soon as I see that they are ready to cry ‘Eureka,’ I’m off.”

“Don’t be too sure,” said another big fairy. “Look at our old pal, we used to call Vonk. In playful moods, he liked to rub the cat’s back on winter mornings, and make sparks from poor pussy fly out. Or, with bits of amber, in friction, he could draw up a hair, or a scrap of paper; but when mad, would leap out of the sky in a lightning flash, or come down in a fire-bolt, that would set a house in flames.”

“Who ever thought that a fairy, with such power, could be caught? But he was. First they put him in a jar. Then they drew him from the clouds, with a kite and key. Then they made him dance the tight rope on wires, and carry messages a thousand miles on land. Now, they [35]stretch an iron clothes-line under the sea, and keep him all the time waltzing backwards and forwards between Europe and America. Now, again, they have made a harness of batteries and wires, and, with his help, they write and talk to each other at the ends of the earth. They gabble about ‘receivers’ and ‘volts’ and a thousand things we cannot understand; but, with their submarine cables and overland wires, and wireless stations, they have beaten our English neighbor Puck; for they have ‘put a girdle round the earth in forty minutes.’ Besides this, they make this fairy, who was a former member of our family, do all sorts of work, even to toasting, cooking and scrubbing and washing and ironing clothes. Worse than all, where we used to have control of the air, and keep men out of it, now they have put Vonk in a machine with wings, and a motor to drive it through the sky and across the ocean.”

So it went on, in the fairy world. First one, and then the other, told how human beings were doing what, long ago, only the fairies and none else could do. Things were different now, because men had kidnapped some of the fairies, and harnessed them to work, as if they were horses or dogs, or donkeys; that’s the reason they are so smart.

“We shall all be caught, by and bye,” grumbled [36]a young and very lazy fairy. “Men will catch and drag us out, just as fish are caught in nets, or pulled out by hook and line. Who can, who will escape these mortals?”

“There won’t be any fairies left in Belgic land,” wailed another who seemed ready to cry.

“We’ll all be no better than donkeys,” sobbed another. “I know we shall.”

So after a long chat, it was proposed that a delegation should wait on the king of the fairies, to ask him to call a convention of all his subjects, of every sort and kind, to see what could be done in the matter. It would not do to let things go on at this rate, or there would not be one fairy left; but all would become servants, slaves, or beasts of burden for human beings. They might even make the fairies wear iron clothes, so they should have no freedom, except as their masters willed: and, even women would be their bosses.

They agreed unanimously to hold the Congress, or Convention, at Kabouterberg, or the Hill of the Kabouters, near Gelrode. All promised to lay aside their grudges, and forget all social slights and quarrels. Even the sooty elves, from the deep mines, were to be given the same welcome and to be treated with the same politeness, as the silvery fairies of the meadows, that were as fresh as flowers and sparkling as [37]sapphires. It was agreed that none should laugh, even if one of the Kluddes should try to talk in meeting.

The invitations were sent out to every sort of fairy known in Belgium, from Flanders to Luxemburg, and from the sandy campine of Limburg, to the flax fields of Hainault. Over land and sea, and from the bowels of the earth, from down in the coal and zinc mines, to the highest hill of the Ardennes, the invitations were sent out. Not one was forgotten.

Of course, not every individual fairy could come, but only committees or delegations of each sort.

It would be too long a story to tell of all who did come and what they said and how they behaved; but from the secretary of the meeting, the story-teller obtained the list of delegates. The principal personages were as follows:

Honors were paid first to the smallest. These were the Manneken, or little fellows. They stood not much higher than a thimble, but were very merry. The Manneken had triangular heads, and their eyes always twinkled. They were very much like children, that do not show off before company, but are often very bright and cunning, when you do not expect them to be.

Their usual occupation was to play tricks on servant girls and lads, milkmaids, ostlers, [38]farmers and the people that lived in the woods or among the dunes. The general tint of their clothes and skin was brown. Sometimes people called them Mannetje, or Darling Little Fellows. They and the rabbits were great friends.

Next came our old friends, the Kabouters, whom we have met before. Living down in the earth, and in the mines, and always busy at forge fires, or in coal or ore, they were not expected to come daintily dressed. They seemed, however, to have brushed off the soot, washed away the grime, and scrubbed themselves up generally. Too much light seemed to disturb them and all the time they kept shading their eyes with their hands. The majority were dressed in suits, caps, and shoes of a butternut color. Each one was about a yard high. They were cousins to the Kobolds of Germany.

The Klabbers were easily picked out of the crowd, by their scarlet caps, and because they were dressed in red, from head to foot. Most of them had green faces and green hands. They were very polite and jolly, but sometimes they appeared to be surly and snarlish, according to the moods they were in, but more especially because of the way they were treated by others. It is said that there was more of human nature in these fellows, than in any other kind of Belgian fairies. These Klabbers, or Red Caps, were somewhat taller than the Kabouters. [39]

There were not many of the Kluddes, for these clownish fellows, who lived in the Campine, among the sand dunes, or by the sea shore, or loafed along country roads, or by the side of ditches, with no good purpose, hardly knew how to behave in the company of well bred, or even decent fairies. Even the Kabouters, not one of whom owned a dress coat, or a fashionable gown, had better manners than the Kludde rascals, whose one idea seemed to be to tumble farmers’ boys into the ditches. They had no originality, or variety in their tricks, beyond the single one of changing themselves into old “plugs,” or broken down horses; and they possessed no more powers of speech, than cows or cats, that say “moo” and “miouw.” They could understand the talk of the other fairies, but could not themselves speak, having no tongues.

When a fairy stood up that was fluent, and entertaining, and made a good speech, these sand snipes applauded so loudly, and kept on crying “Kludde” so noisily—the only word they knew—that the president of the meeting had to call them to order. He sternly told them to be silent, or he would have them put out. Notwithstanding this, they kept on mumbling, “Kludde, Kludde” to themselves.

The Wappers were out in full force, or at least a dozen of them. At first they sat folded [40]up, like jackknives; and all occupying one place together, like a lot of beetles; but when the place of meeting got crowded, by others wanting their room, the Wappers stretched themselves out and up, until they looked like a crowd of daddy longlegs, with their long, wiry limbs and their heads and bodies up in the air. They were told not to talk gibberish, except among themselves; but to address the chair, and speak in meeting only in correct and polite fairy language, which even then had to be interpreted.

No jokes or tricks, such as the different kinds of fairies play on human beings, were allowed during the meeting of the Congress.

Two big, fairy policemen, called Gog and Magog, dressed in the colors of the Belgian flag, black, yellow and red, were posted near the door, to make all Kabouters, Kludde, Wappers and Mannekens, behave. If any member of the Congress got too “fresh,” or obstreperous, he was immediately seized and thrown out of doors.

Both the policemen’s clubs, which were longer than barbers’ poles, were made of Flemish oak, wrapped round with black, yellow and red ribbons. Besides these bludgeons, each carried at his belt a coil of rope, to bind any of the big fairies that might give trouble.

No wash or bath tubs, aquariums, hogsheads, or barrels, having been provided, nor any salt [41]water being at hand, there were no mermaids or mermen present.

No ogres or giants came, for it could not be found that any of these big fairy folk lived in the Belgium of our time. Formerly, they were very numerous and troublesome, not only to men and women, but even to the pretty and respectable fairies.

As for old Toover Hek, and his wife, Mrs. Hek, they had never been heard of, or from, for hundreds of years. Much the same report concerning dragons was given by the registrar, or secretary, who knew all about the different kind of Belgian fairies.

At the name of a certain mortal, Balthazar Bekker, the Dutch enemy of all fairies, every one hissed, the Kabouters howled, the Wappers banged tin pans, and the Kludde yelled. One fairy proposed the health of Toover Hek, as an insult to Bekker’s memory, but this was voted down as an extreme measure. Then it was suggested that the memory of Verarmen of Hasselt be praised, but those present in the Congress, being modern fairies, cared nothing about anything so far back.

As for the regular attendants at the Congress, they were many and interesting, and some were very lovely; yet, altogether, they were much, in their looks and manners, like the fairies in other [42]countries; so that there is little advantage to be gained in describing them, or their dresses and ornaments. Some had wings, some had not. They looked very gauzy, and most of them were as tiny as babies, but there were some larger ones also.

One of the first laws passed at the Congress was a Foreign Fairy Exclusion Law! This was done at the suggestion of a member of the Kabouters’ Guild, who was afraid the Belgian fairies would be ruined by the cheap labor imported from other countries, like Ireland or Bulgaria.

It was also unanimously decided that no foreign fairies, even if they applied for membership, or wanted to attend as visitors, should be admitted to the Congress. So all the German kobolds, English brownies and nixies, Japanese oni, the French fee, Austrian gnomes, and the Scotch and Irish fays and fairies, of any and all kinds, were kept out. Though these might envy the fairies of Belgium, and their happy lot, they could not even sit as delegates, or be allowed the usual courtesies due to visitors.

This the story teller heard afterwards, when a fairy maiden let out the secret of this, one of the proceedings of the Congress, after they had gone into executive session! She just couldn’t keep a secret, that’s all! [43]

“And why do we not report especially more of what was said and done behind the closed doors, or tell about the social side of the Congress,” does any one ask. Or why does he not tell more about the amusements, the receptions, and the fine clothes of the prettiest fairies?

Well, the American man was vexed enough, when the president of the Congress ordered all human beings and strangers of every sort to leave the house, and then locked the door, so that everything was done in secret.

This was the only time in Belgium, that the story-teller was not courteously treated. Yet the reason is plain. The President and secretary were both afraid that this tourist, who had really, many times visited Belgium, just to get better acquainted with the fairies, was a prude, who didn’t believe in letting children know anything about fairies. In other words, he was suspected of wanting to abolish all books of fairy tales from the libraries.

But you know better. [44]

V

THE OGRE IN THE FOREST OF HAZEL NUTS

Ages ago, in the gloomy forests of Limburg, there lived a roaring giant named Toover Hek. Although the forest was so dense, yet there were many paths through it, for there was no other way of getting across from Germany, into Belgic Land and France and Holland. Toover Hek, the man-eating giant, or ogre, used to wait, where the paths crossed each other, or diverged, and here he would waylay travelers, seize them and run away with them, and, with his ogre wife, devour them in his cave.

This ogre, Toover Hek, roamed the woods and ate up all the people he could catch, who traveled that way. Terrible tales were told about his vrouw, also, who was reported to be even more cruel than her big husband. It was said that she was a cousin of another ogre, Hecate, who had once lived further east, in Greece. Both had been driven out by the holy saints, and had come into Belgic land, where [45]one of them married the man-eating giant, Toover Hek.

Sometimes the children called this big fellow the Long Man, because he was so tall, and had such very long legs. In the local dialect, this became “Lounge Man,” which means the same thing.

One day, his ogre wife found some honey in the forest and brought it to him. He smacked his lips and always after that called his wife his Troetel, or Honey Bunch.

The first inhabitant of the country was a farmer, named Heinrich. He was a doughty fellow, who was not afraid of ogres or giants. He had long lived among people who celebrated the kermiss, but with such drunken brutality and coarse indecency, that he was disgusted, and went into the forest to live. Heinrich’s one weakness was pea soup, and his wife thought with him and rode the same hobby. All her neighbors said that she made the best and thickest pea soup in Limburg. Heinrich believed pea soup to be both food and luxury. He thought also that water and milk, and good soup, were all the liquids nature intended ever to pass the human throat.

Finding that the soil was fertile, and that plenty of hazel nuts would fatten his pigs, Heinrich trudged with his wife Grietje (Maggie), [46]far into the hazel forest. He swung his axe diligently, chopped down the trees, and built a rough house of wood. This he made his home, and named it Hasselt.

Soon his goats, pigs, and chickens so multiplied that it was hard to keep them out of the house. So Grietje persuaded her husband, Heinrich, to saw the door in halves and put them on two sets of hinges. This was called a hek, or heck-door, after the name usually given to the feed-rack in the barn or stable.

In this way, the upper part of the door, when open, let in light and air, and the house was kept looking sweet and cheerful. The lower part of the door, or the heck, when shut, kept out the goats, pigs, and chickens.

Leaning over the top of the lower half, the good vrouw could throw out grain to feed the ducks, geese, pullets, hens, and roosters, and toss many a tidbit to the piggies. Farmer Heinrich was so pleased with this idea of a double door, that kept his wife in good humor, that he would always call on it to witness some act of his. He would even swear by this demi-door, as if it were something sacred or important.

So his wife often heard him say “By heck, that’s a fine hazel-nut,” or “By heck, what a fat pig!” or, “By heck, that pea soup is good!” and many such like expressions. [47]

Being so extravagantly fond of the thick pea soup, which Belgians like so much, Heinrich planted a large pea patch. Every day, he went out to see how his vines were growing. When his crop was ready to be gathered, he had, besides having enjoyed a daily dish of green peas, or a good basin of thick pea soup, enough of the legumes dried, to furnish his table with thick pea soup, all winter long. He cultivated all the varieties of peas then known. The early, medium, late, and the wrinkled, smooth or split peas were, at one time or another, on his table.

One evening, after a day’s work with the axe, in the forest, Farmer Heinrich came home to tell his wife about a terrible ogre, of which he had caught a glimpse, that day, on one of the hills across the valley. This monster carried an enormous fir tree club.