Korean Fairy Tales

William Elliot Griffis

KOREAN FAIRY TALES

BOOKS BY WM. ELLIOT GRIFFIS

- BELGIAN FAIRY TALES

- DUTCH FAIRY TALES

- JAPANESE FAIRY TALES

- KOREAN FAIRY TALES

- SWISS FAIRY TALES

- WELSH FAIRY TALES

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

The tiger climbed up and out.

FAIRY TALES

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1911 and 1922

By THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America [v]

A NOTE TO THE FRIENDS OF KOREA

Everywhere on earth the fairy world of each country is older and perhaps more enduring than the one we see and feel and tread upon. So I tell in this book the folk lore of the Korean people, and of the behavior of the particular kind of fairies that inhabit the Land of Morning Splendor. Yet, if I live long enough, I shall write the wonderful history of the Korean nation and civilization, which once so enriched Asia, and made possible the modern Japan such as we know today, of which fact the literature and art of both countries bear ample witness.

W. E. G. [vii]

CONTENTS

- PAGE

- The Unmannerly Tiger 1

- Tokgabi and His Pranks 6

- East Light and the Bridge of Fishes 11

- Prince Sandalwood, the Father of Korea 17

- The Rabbit’s Eyes 24

- Topknots and Crockery Hats 30

- Fancha and the Magpie 38

- The Sneezing Colossus 49

- A Bridegroom for Miss Mole 53

- Old White Whiskers and Mr. Bunny 59

- The King of the Flowers 65

- Tokgabi’s Menagerie 71

- Cat-kin and the Queen Mother 78

- The Magic Peach 89

- The Great Stone Fire Eater 102

- Pigling and Her Proud Sisters 110

- The Mirror that Made Trouble 117

- Old Timber Top 130

- Sir One Long Body and Madame Thousand Feet 147

- The Sky Bridge of Birds 155

- Longka, the Dancing Girl 161

- A Frog for a Husband 167

- Shoes for Hats 179

- The Voice of the Bell 187

- The King of the Sparrows 195

- The Woodman and the Mountain Fairies 204

[1]

List of Illustrations

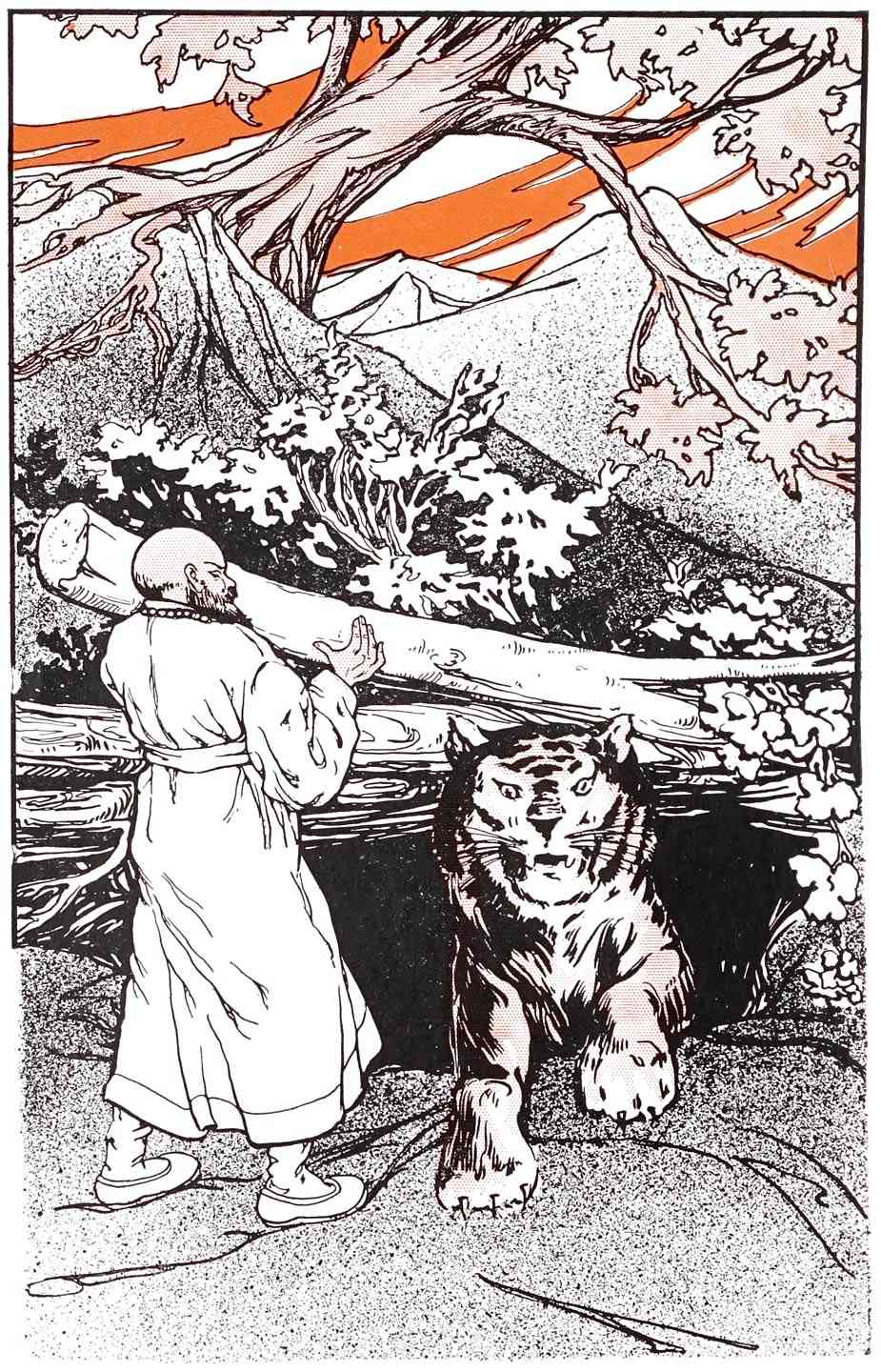

- The tiger climbed up and out.

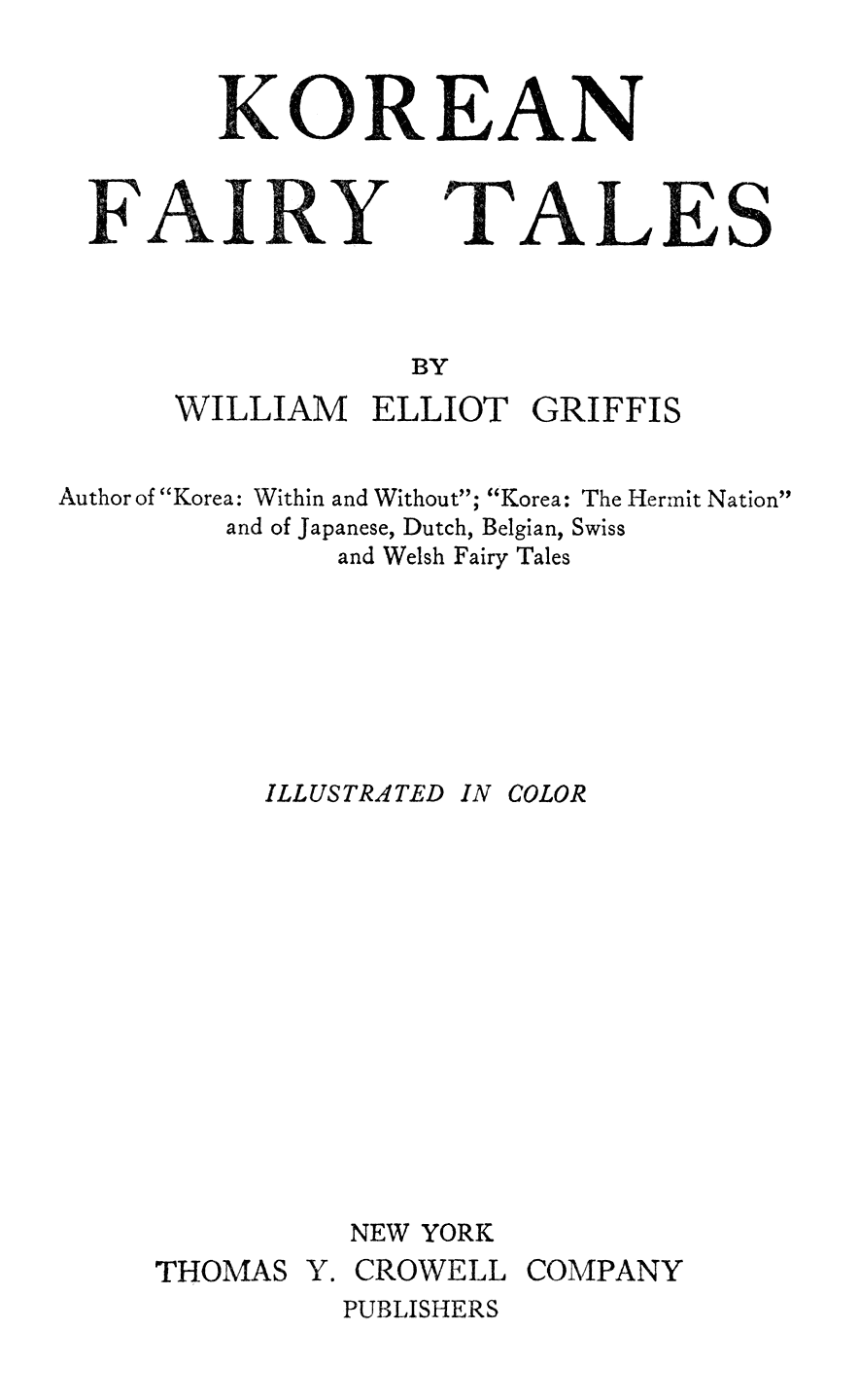

- Shouted East Light, “Let us flee!” 14

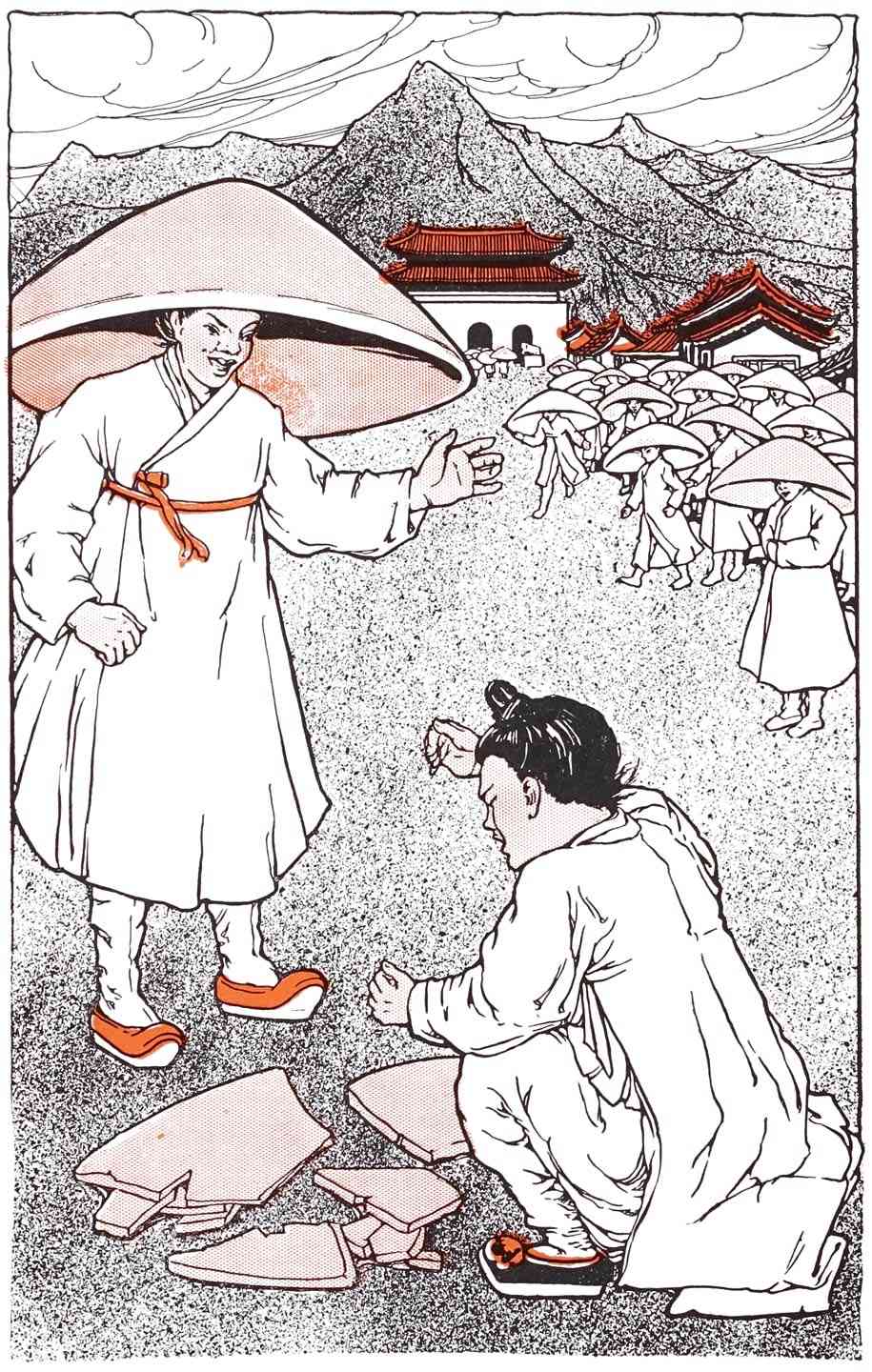

- They cracked their crockery. 34

- With patience Miryek listened to the proud father. 56

- A party of children caught sight of the odd pair. 76

- She heard a whir and a rush of wings. 110

- The lovely lady that stands by the starry river to meet her lord. 160

- All the children clapped their hands. 192

KOREAN FAIRY TALES

THE UNMANNERLY TIGER

“Mountain Uncle” was the name given by the villagers to a splendid striped tiger that lived among the highlands of Kang Wen, the long province which from its cliffs overlooks the Sea of Japan. Hunters rarely saw him, and among his fellow-tigers the Mountain Uncle boasted that, though often fired at, he had never been wounded; while as for traps—he knew all about them and laughed at the devices used by man to catch him and to strip him of his coveted skin. In summer he kept among the high hills and lived on fat deer. In winter, when heavy snow, biting winds, and terrible cold kept human beings within doors, old Mountain Uncle would sally forth to the villages. There he would prowl around the stables, the cattle enclosures, or the pig pens, in hopes of clawing and dragging out a young donkey, a fat calf, or a suckling pig. Too often he succeeded, so that he was the terror of the country for leagues around.

One day in autumn, Mountain Uncle was rambling among the lower hills. Though far from any [2]village, he kept a sharp lookout for traps and hunters, but none seemed to be near. He was very hungry and hoped for game.

But on coming round a great rock, Mountain Uncle suddenly saw in his path some feet ahead, as he thought, a big tiger like himself.

He stopped, twitched his tail most ferociously as a challenge, showed fight by growling, and got ready to spring. What was his surprise to see the other tiger doing exactly the same things. Mountain Uncle was sure there would be a terrible struggle, but this was just what he wanted, for he expected to win.

But after a tremendous leap in the air he landed in a pit and all of a heap, bruised and disappointed. There was no tiger to be seen, but instead a heavy lid of logs had closed over his head with a crash and he lay in darkness. Old Mountain Uncle was caught at last. Yes, the hunter had concealed the pit with sticks and leaves, and on the upright timbers, covered with vines and brushwood, had hung a looking-glass. Mountain Uncle had often beheld his own face and body in the water, when he stooped to drink, but this time not seeing any water he was deceived into thinking a real tiger wanted to fight him.

By and by, a Buddhist priest came along, who believed in being kind to all living creatures. Hearing an animal moaning, he opened the trap [3]and lifting the lid saw old Mountain Uncle at the bottom licking his bruised paw.

“Oh, please, Mr. Man, let me get out. I’m hurt badly,” said the tiger.

Thereupon the priest lifted up one of the logs and slid it down, until it rested on the bottom of the pit. Then the tiger climbed up and out. Old Mountain Uncle expressed his thanks volubly, saying to the shaven head:

“I am deeply grateful to you, sir, for helping me out of my trouble. Nevertheless, as I am very hungry, I must eat you up.”

The priest, very much surprised and indignant, protested against such vile ingratitude. To say the least, it was very bad manners and entirely against the law of the mountains, and he appealed to a big tree to decide between them.

The spirit in the tree spoke through the rustling leaves and declared that the man should go free and that the tiger was both ungrateful and unmannerly.

Old Mountain Uncle was not satisfied yet, especially as the priest was unusually fat and would make a very good dinner. However, he allowed the man to appeal once more and this time to a big rock.

“The man is certainly right venerable Mountain Uncle, and you are wholly wrong,” said the spirit in the rock. “Your master, the Mountain [4]Spirit, who rides on the green bull and the piebald horse to punish his enemies, will certainly chastise you if you devour this priest. You will be no fit messenger of the Mountain Lord if you are so ungrateful as to eat the man who saved you from starvation or death in the trap. It is shockingly bad manners even to think of such a thing.”

The tiger felt ashamed, but his eyes still glared with hunger; so, to be sure of saving his own skin, the priest proposed to make the toad a judge. The tiger agreed.

But the toad, with his gold-rimmed eyes, looked very wise, and instead of answering quickly, as the tree and rock did, deliberated a long time. The priest’s heart sank while the tiger moved his jaws as if anticipating his feast. He felt sure that Old Speckled Back would decide in his favor.

“I must go and see the trap before I can make up my mind,” said the toad, who looked as solemn as a magistrate. So all three leaped, hopped, or walked to the trap. The tiger, moving fast, was there first, which was just what the toad, who was a friend of the priest, wanted. Besides, Old Speckled Back was diligently looking for a crack in the rocks near by.

So while the toad and the tiger were studying the matter, the priest ran off and saved himself within the monastery gates. When at last Old Speckled Back decided against Mountain Uncle [5]and in favor of the man, he had no sooner finished his judgment than he hopped into the rock crevice, and, crawling far inside defied the tiger, calling him an unmannerly brute and an ungrateful beast, and daring him to do his worst.

Old Mountain Uncle was so mad with rage and hunger that his craftiness seemed turned into stupidity. He clawed at the rock to get at the toad, but Speckled Back, safe within, only laughed. Unable to do any harm, the tiger flew into a passion of rage. The hotter his temper grew, the more he lost his wit. Poking his nose inside the crack he rubbed it so hard on the rough rock that he soon bled to death.

When the hunter came along he marveled at what he saw, but he was glad to get rich by selling the tiger’s fur, bones, and claws; for in Korea nothing sells so well as a tiger. As for the toad, he told to several generations of his descendants the story of how he outwitted the old Mountain Uncle. [6]

TOKGABI AND HIS PRANKS

Tokgabi is the most mischievous sprite in all Korean fairy-land. He does not like the sunshine or outdoors, and no one ever saw him on the streets.

He lives in the sooty flues that run under the floors along the whole length of the house, from the kitchen at one end of it to the chimney hole in the ground at the other end. He delights in the smoke and smut, and does not mind fire or flame, for he likes to be where it is warm. He has no lungs, and his skin and eyes are both fire-proof. He is as black as night and loves nothing that has white in it. He is always afraid of a bit of silver, even if it be only a hairpin.

Tokgabi likes most to play at night in the little loft over the fireplace. To run along the rafters and knock down the dust and cobwebs is his delight. His favorite game is to make the iron rice-pot lid dance up and down, so that it tumbles inside the rice kettle and cannot easily be got out again. Oh, how many times the cook burns, scalds, or steams her fingers in attempting to fish out that [7]pot lid when Tokgabi has pushed it in! How she does bless the sooty imp!

But Tokgabi is not always mischievous, and most of his capers hurt nobody. He is such a merry fellow that he keeps continually busy, whether people cry or laugh. He does not mean to give any one trouble, but he must have fun every minute, especially at night.

When the fire is out, how he does chase the mice up and down the flues under the floor, and up in the garret over the rafters! When the mousies lie dead on their backs, with their toes turned upward, the street boys take them outdoors and throw them up in the air. Before the mice fall to the ground, the hawks swoop down and eat them up. Many a bird of prey gets his breakfast in this way.

Although Tokgabi plays so many pranks, he is kind to the kitchen maids. When after a hard day’s work one is so tired out that she falls asleep, he helps her to do her hard tasks.

Tokgabi washes their dishes and cleans their tables for good servants; so when they wake up the girls find their work done for them. Many a fairy tale is told about this jolly sprite’s doings—how he gives good things to the really nice people and makes the bad ones mad by spitefully using them. They do say that the king of all the Tokgabis has a museum of curiosities and a storehouse full of gold and gems and fine clothes, and everything [8]sweet to eat for good boys and girls and for old people that are kind to the birds and dumb animals. For bad folks he has all sorts of things that are ugly and troublesome. He punishes stingy people by making them poor and miserable.

The Tokgabi king has also a menagerie of animals. These he sends to do his errands rewarding the good and punishing naughty folks. Every year the little almanac with red and green covers tells in what quarter of the skies the Tokgabi king lives for that year, so that the farmers and country people will keep out of his way and not provoke him. In his menagerie the kind creatures that help human beings are the dragon, bear, tortoise, frog, dog and rabbit. These are all man’s friends. The cruel and treacherous creatures in Tokgabi’s menagerie are the tiger, wild boar, leopard, serpent, toad and cat. These are the messengers of the Tokgabi king to do his bidding, when he punishes naughty folks.

The common, every-day Tokgabi plays fewer tricks on the men and boys and enjoys himself more in bothering the girls and women. This, I suppose, is because they spend more time in the house than their fathers or brothers. In the Land of Rat-tat-tat, where the sound of beating the washed clothes never ceases, Tokgabi loves to get hold of the women’s laundry sticks which are used for pounding and polishing the starched clothes. He hides them so that they cannot be found. Then [9]Daddy makes a fuss because his long white coat has to go without its usual gloss, but it is all Tokgabi’s fault.

Tokgabi does not like starch because it is white. He loves to dance on Daddy’s big black hat case that hangs on the wall. Sometimes he wiggles the fetich, or household idol, that is suspended from the rafters. But, most of all, he enjoys dancing a jig among the dishes in the closet over the fireplace, making them rattle and often tumble down with a crash.

Tokgabi likes to bother men sometimes too. If Daddy should get his topknot caught in a rat hole, or his head should slip off his wooden pillow at night and he bump his nose, it is all Tokgabi’s fault. When anything happens to a boy’s long braid of hair, that hangs down his back and makes him look so much like a girl, Tokgabi is blamed for it. It is even said that naughty men make compacts with Tokgabi to do bad things, but the imp only helps the man for the fun of it. Tokgabi cares nothing about what mortal men call right or wrong. He is only after fun and is up to mischief all the time, so one must watch out for him.

The kitchen maids and the men think they know how to circumvent Tokgabi and spoil his tricks. Knowing that the imp does not like red, a young man when betrothed wears clothes of this bright color. Tokgabi is afraid of shining silver, too, so [10]the men fasten their topknots together, and the girls keep their chignons in shape, with silver hairpins. The magistrates and government officers have little storks made of solid silver in their hats, or else these birds are embroidered with silver thread on their dresses. Every one who can afford them uses white metal dishes and dresses in snowy garments. Tokgabi likes nothing white and that is the reason why every Korean likes to put on clothes that are as dazzling as hoar frost. Tons and mountains of starch are consumed in blanching and stiffening coats and skirts, sleeves and stockings. On festival days the people look as if they were dipped in starch and their garments encrusted in rock candy. In this manner they protect themselves from the pranks of Tokgabi. [11]

EAST LIGHT AND THE BRIDGE OF FISHES

Long, long ago, in the region beyond the Everlasting White Mountains of Northern Korea, there lived a king who was waited on by a handsome young woman servant. Every day she gladdened her eyes by looking southward, where the lofty mountain peak which holds the Dragon’s Pool in its bosom lifts its white head to the sky. When tired out with daily toil she thought of the river that flows from the Dragon’s Pool down out of the mountain. She hoped that some time she would have a son that would rule over the country which the river watered so richly.

One day while watching the mountain top she saw coming from the east a tiny bit of shining vapor. Floating like a white cloud in the blue sky it seemed no bigger than an egg. It came nearer and nearer until it seemed to go into the bosom of her dress. Very soon she became the mother of a boy. It was indeed a most beautiful child.

But the jealous king was angry. He did not like the little stranger. So he took the baby and threw it down among the pigs in the pen, thinking that [12]this would be the last of the boy. But no! the sows breathed into the baby’s nostrils and their warm breath made it live.

When the king’s servants heard the little fellow crowing, they went out to see what made the noise, and there they beheld a happy baby not seeming to mind its odd cradle at all. They wanted to give him food at once but the angry king ordered the child to be thrown away, and this time into the stable. So the servants took the boy by the legs and laid him among the horses, expecting that the animals would tread on him and he would be thus put out of the way.

But no, the mares were gentle, and with their warm breath they not only kept the little fellow from getting cold, but they nourished him with their milk so that he grew fat and hearty.

When the king heard of this wonderful behavior of pigs and horses, he bowed his head toward Heaven. It seemed the will of the Great One in the Sky that the boy baby should live and grow up to be a man. So he listened to its mother’s prayers and allowed her to bring her child into the palace. There he grew up and was trained like one of the king’s sons. As a sturdy youth, he practiced shooting with bow and arrows and became skilful in riding horses. He was always kind to animals. In the king’s dominions any man who was cruel to a horse was punished. Whoever struck a mare so [13]that the animal died, was himself put to death. The young man was always merciful to his beasts.

So the king named the youthful archer and horseman East Light, or Radiance of the Morning and made him Master of the Royal Stables. East Light, as the people liked to say his name, became very popular. They also called him Child of the Sun and Grandson of the Yellow River.

One day while out on the mountains hunting deer, bears, and tigers, the king called upon the young archer to show his prowess in shooting arrows. East Light drew his bow and showed skill such as no one else could equal. He sent shaft after shaft whistling into the target and brought down both running deer and flying birds. Then all applauded the handsome youth. But instead of the king’s commending East Light, the king became very jealous of him, fearing that he might want to seize the throne. Nothing that the young man could do seemed now to please his royal master.

Fearing he might lose his life if he remained near the king, East Light with three trusty followers fled southward until he came to a great, deep river, wide and impassable. How to get across he knew not, for no boat was at hand and the time was too short to make a raft, for behind him were his enemies swiftly pursuing.

In a great strait, he cried out: [14]

“Alas, shall I, the Child of the Sun and the Grandson of the Yellow River, be stopped here powerless by this stream?”

Then as if his father, the Sun, had whispered to him what to do, he drew his bow and shot many arrows here and there into the water, nearly emptying his quiver.

For a few moments nothing happened. To his companions it seemed a waste of good weapons. What would their leader have left to fight his pursuers when they appeared, if his quiver were empty?

But in a moment more the waters appeared to be strangely agitated. Soon they were flecked and foaming. From up and down the stream, and in front of them, the fish were swimming toward East Light, poking their noses out of the water as if they would say:

“Get on our backs and we’ll save you.” They crowded together in so dense a mass that on their spines a bridge was soon formed, on which men could stand.

“Quick!” shouted East Light to his companions, “let us flee! Behold the king’s horsemen coming down the hill after us.”

Shouted East Light, “Let us flee!”

So over the bridge of fish backs, scaly and full of spiny fins, the four young men fled. As soon as they gained the opposite shore, the bridge of fishes dissolved. Yet scarcely had they swum away, [15]when those who were in pursuit had gained the water’s edge, on the other side. In vain the king’s soldiers shot their arrows to kill East Light and his three companions. The shafts fell short and the river was too deep and wide to swim their horses over. So the four young men escaped safely.

Marching on farther a few miles, East Light met three strange persons who seemed to be awaiting his coming. They welcomed him warmly and invited him to be their king and rule over their city. The first was dressed in seaweed, the second in hempen garments, and the third in embroidered robes. These men represented the three classes of society; first fishermen and hunters; second farmers and artisans; and lastly rulers of the tribes.

So in this land named Fuyu, rich in the five grains, wheat, rice, and millet, bean and sugarcane, the new king was joyfully welcomed by his new subjects. The men were tall, brave and courteous. Besides being good archers, they rode horses skilfully. They ate out of bowls with chop-sticks and used round dishes at their feasts. They wore ornaments of large pearls and jewels of red jade cut and polished.

The Fuyu people gave the fairest virgin in their realm to be the bride of King East Light and she became a gracious queen, greatly beloved of her subjects and many children were born to them.

East Light ruled long and happily. Under his [16]reign the people of Fuyu became civilized and highly prosperous. He taught the proper relations of ruler and ruled and the laws of marriage, besides better methods of cooking and house-building. He also showed them how to dress their hair. He introduced the wearing of the topknot. For thousands of years topknots were the fashion in Fuyu and in Korea.

Hundreds of years after East Light died, and all the tribes and states in the peninsula south of the Everlasting White Mountains wanted to become one nation and one kingdom, they called their country after East Light, but in a more poetical form,—Cho-sen, which means Morning Radiance, or the Land of the Morning Calm. [17]

PRINCE SANDALWOOD, THE FATHER OF KOREA

Four little folks lived in the home of Mr. Kim, two girls and two boys. Their names were Peach Blossom and Pearl, Eight-fold Strength and Dragon. Dragon was the oldest, a boy. Grandma Kim was very fond of telling them stories about the heroes and fairies of their beautiful country.

One evening when Papa Kim came home from his office in the Government buildings, he carried two little books in his hand, which he handed over to Grandma. One was a little almanac looking in its bright cover of red, green and blue as gay as the piles of cakes and confectionery made when people get married; for every one knows how rich in colors are pastry and sweets for the bride’s friends at a Korean wedding party.

The second little book contained the direction sent out by the Royal Minister of Ceremonies for the celebration of the festival in honor of the Ancestor-Prince, Old Sandalwood, the Father of Korea. Twice a year in Ping Yang City they made [18]offerings of meat and other food in his honor, but always uncooked.

“Who was old Sandalwood?” asked Peach Blossom, the older of the little girls.

“What did he do?” asked Yongi (Dragon), the older boy.

“Let me tell you,” said Grandma, as they cuddled together round her on the oiled-paper carpet over the main flue at the end of the room where it was warmest; for it was early in December and the wind was roaring outside.

“Now I shall tell you, also, why the bear is good and the tiger bad,” said Grandma. “Well, to begin——

“Long, long ago, before there were any refined people in the Land of Dawn, and no men but rude savages, a bear and a tiger met together. It was on the southern slope of Old Whitehead Mountain in the forest. These wild animals were not satisfied with the kind of human beings already on the earth, and they wanted better ones. They thought that if they could become human they would be able to improve upon the quality. So these patriotic beasts, the bear and the tiger, agreed to go before Hananim, the Great One of Heaven and Earth, and ask him to change at once their form and nature; or, at least, tell them how it could be done.

“But where to find Him—that was the question. [19]So they put their heads down in token of politeness, stretched out their paws and waited a long while, hoping to get light on the subject.

“Then a Voice spoke out saying, ‘Eat a bunch of garlic and stay in a cave for twenty-one days. If you do, you will become human.’

“So into the dark cave they crawled, chewed their garlic and went to sleep.

“It was cold and gloomy in the cave and with nothing to hunt or eat, the tiger got tired. Day after day he moped, snarled, growled and behaved rudely to his companion. But the bear bore the tiger’s insults.

“Finally on the eleventh day, the tiger, seeing no signs of losing his stripes or of shedding his hair, claws or tail, and with no prospect of fingers or toes in view, concluded to give up trying to become a man. He bounded out of the cave and at once went hunting in the woods, going back to his old life.

“But the bear, patiently sucking her paw, waited till the twenty-one days had passed. Then her hairy hide and claws dropped off, like an overcoat. Her nose and ears suddenly shortened and she stood upright—a perfect woman.

“Walking out of the cave the new creature sat beside a brook, and in the pure water beheld how lovely she was. There she waited to see what would take place next. [20]

“About this time while these things were going on down in the world matters of interest were happening in the skies. Whanung, the Son of the Great One in the Heavens, asked his father to give him an earthly kingdom to rule over. Pleased with his request, the Lord of Heaven decided to present his son with the Land of the Dragon’s Back, which men called Korea.

“Now as everybody knows, this country of ours, the Everlasting Great Land of the Dayspring, rose up on the first morning of creation out of the sea, in the form of a dragon. His spine, loins and tail form the great range of mountains that makes the backbone of our beautiful country, while his head rises skyward in the eternal White Mountain in the North. On its summit amid the snow and ice lies the blue lake of pure water, from which flow out our boundary rivers.”

“What is the name of this lake?” asked Yongi the boy.

“The Dragon’s Pool,” said Grandma Kim, “and during one whole night, ever so long ago, the dragon breathed hard and long until its breath filled the heavens with clouds. This was the way that the Great One in the Skies prepared the way for his son’s coming to earth.

“People thought there was an earthquake, but when they woke up in the morning and looked up to the grand mountain, so gloriously white, [21]they saw the cloud rising far up in the sky. As the bright sun shone upon it, the cloud turned into pink, red, yellow and the whole eastern sky looked so lovely that our country then received its name—the Land of Morning Radiance.

“Down out of his cloud of many colors, and borne on the wind, Whanung, the Heavenly Prince, descended first to the mountain top, and then to the lower earth. When he entered the great forest he found a beautiful woman sitting by the brookside. It was the bear that had been transformed into lovely human shape and nature.

“The Heavenly Prince was delighted. He chose her as his bride and, by and by, a little baby boy was born.

“The mother made for her son a cradle of soft moss and reared her child in the forest.

“Now the people who dwelt at the foot of the mountain were in those days very rude and simple. They wore no hats, had no white clothes, lived in huts, and did not know how to warm their houses with flues running under the floors, nor had they any books or writings. Their sacred place was under a sandalwood tree, on a small mountain named Tabak, in Ping Yang province.

“They had seen the cloud rising from the Dragon’s Pool so rich in colors, and as they looked they saw it move southward and nearer to them, until it stood over the sacred sandalwood tree; [22]when out stepped a white-robed being, and descending through the air alighted in the forest and on the tree.

“Oh, how beautiful this spirit looked against the blue sky! Yet the tree was far away and long was the journey to it.

“ ‘Let us all go to the sacred tree,’ said the leader of the people. So together they hied over hill and valley until they reached the holy ground and ranged themselves in circles about it.

“A lovely sight greeted their eyes. There sat under the tree a youth of grand appearance, arrayed in princely dress. Though young looking and rosy in face, his countenance was august and majestic. Despite his youth, he was wise and venerable.

“ ‘I have come from my ancestors in Heaven to rule over you, my children,’ he said, looking at them most kindly.

“At once the people fell on their knees and all bent reverently, shouting:

“ ‘Thou art our king, we acknowledge thee, and will loyally obey only thee.’

“Seeing that they wanted to know what he could tell them, he began to instruct them, even before he gave them laws and rules and taught them how to improve their houses. He told them stories. The first one explained to them why it was that the bear is good and the tiger bad. [23]

“The people wondered at his wisdom, and henceforth the tiger was hated, while people began to like the bear more and more.

“ ‘What name shall we give our King, so that we may properly address him?’ asked the people of their elders. ‘It is right that we should call him after the place in which we saw him, under our holy tree. Let his title, therefore, be the August and Venerable Sandalwood.’ So they saluted him thus and he accepted the honor.

“Seeing that the people were rough and unkempt, Prince Sandalwood showed them how to tie up and dress their hair. He ordained that men should wear their long locks in the form of a topknot. Boys must braid their hair and let it hang down over their backs. No boy could be called a man, until he married a wife. Then he could twist his hair into a knot, put on a hat, have a head-dress like an adult and wear a long white coat.

“As for the women, they must plait their tresses and wear them plainly at their neck, except at marriage, or on great occasions of ceremony. Then they might pile up their hair like a pagoda and use long hairpins, jewels, silk and flowers.

“Thus our Korean civilization was begun, and to this day the law of the hat and hair distinguishes us above all people,” said Grandma. “We still honor the August and Venerable Prince Sandalwood. Now, good-night, my darlings.” [24]

THE RABBIT’S EYES

There was trouble down in the fish world under the waves. Indeed, every creature with fins and a tail was in distress, for the king of the fishes was suffering with a dreadful pain in his mouth. It had come about in this way.

One day while swimming around in the waters outside his palace, the king of the fishes saw something hanging in the water that looked as if it were good to eat. So at once His Majesty gulped it down, when, oh horrors! he found he had barely escaped swallowing a fish hook, which stuck fast in his gills. It had been baited by some fishermen up in a boat on the sea top. When the king of the fishes found the dreadful thing in his mouth, he jerked himself away. The line broke but the hook remained, giving the king a fever and much pain.

How to get the iron out and heal His Majesty was now the question. All the wise creatures in the ocean, from the turtle to the gudgeon and from the tittleback to the whale, were summoned to the palace to see what could be done. Many [25]a sage noddle was bent, and eye blinked and fin wagged, as the marine doctors talked the matter over in the council. The turtle was considered the most learned and expert of them all. Many were his feelings of the king’s pulse and his looking down into his throat, before Dr. Turtle would pronounce what was the real trouble or write a prescription for his patient. Finally, after consultation with the other doctors that had fins and tails, or were in scales and shell, it was decided that nothing less than a poultice made of rabbits’ eyes would loosen the hook and end His Majesty’s troubles.

So Dr. Turtle was ordered to go to the seashore and invite a rabbit to come down into the world under the sea, that they might make a poultice of his eyes and apply the warm mess to the king’s throat.

Arriving on the sea beach, at the foot of a high hill, Dr. Turtle, looking far up, found Mr. Rabbit out of his burrow and taking a promenade along the edge of the forest. Forthwith Dr. Turtle waddled across the beach and part way up the hill, climbing hard, until he began to puff and blow. He had enough breath left, however, to salute Brother Bunny with a good-morning. Very politely the rabbit returned the greeting.

“It’s a hot day,” said Dr. Turtle, as he pulled [26]out his handkerchief, wiped his horny forehead, and cleaned the sand out of his claws.

“Yes, but the scenery is so fine, Dr. Turtle, that you must be glad you’re out of the water to see such lovely mountains. Don’t you think Korea is a fine country? There is no land in the world so beautiful as ours. The mountains, the rivers, the seashore, the forests, the flowers——”

If Dr. Turtle had let the rabbit run on, praising his own country, he would have forgotten his errand; but, thinking of His Majesty, the suffering fish king, with the cruel hook in his mouth, Dr. Turtle interrupted Bunny, saying:

“Oh, yes, Brother Bunny, this view of the landscape and country is all very beautiful, but it can’t compare to the gems and jewels, trees and flowers, sweet odors and everything lovely down in the world under the sea.”

At this, the rabbit pricked up his ears. It was all new to him. He had never heard that there was anything under the water but common fishes and seaweed and when these were decayed and washed up along the seashore—well, he had his ideas about them. They did not smell sweet at all. Now he heard a different story. His curiosity was roused. “What you tell me, my friend, is interesting. Go on.”

Thereupon Dr. Turtle proceeded to tell of most wonderful mountains and valleys down on the [27]floor of the deep sea, with every kind of rare water plants, red, orange-color, green, blue, white, with trees of gold and silver, besides flowers of every color and delightful perfume.

“You surprise me,” said Brother Bunny, getting more interested.

“Yes, and all sorts of good things to eat and drink, with music and dancing, handsome serving maids and everything nice. Come along and be our guest. Our king has sent me to invite you.”

“May I go?” asked Brother Bunny, delighted.

“Yes, at once. Get on my back and I’ll carry you.”

So the rabbit ran and the turtle waddled to the water’s edge.

“Now hold fast to my front shell,” said Dr. Turtle; “we’re going under the water.”

Down, down below the blue waves they sank until they arrived at the king’s palace. There the rabbit found everything was true, as told by the turtle. The colors, the rich gems were as he had said.

Dr. Turtle introduced Brother Bunny to some of the princes and princesses of the kingdom and these showed their guest the sights and treasures of the palace, while Dr. Turtle attended the council of doctors to announce the success of his errand.

But while Mr. Rabbit was enjoying himself, [28]thinking this was the most wonderful place in the world, he overheard them talking. Then he found out why they had brought him there and shown him such honors. Horrified at the idea of losing his eyes, he determined to save his sight and play the tortoise a smart trick. However, of this he told no one.

So when he was politely informed by the royal executioners that he must give up his eyes to make the king well, Brother Bunny broke out with equally polite regrets:

“Really I am so sorry that His Majesty is ill, and you must excuse me that I cannot help him immediately, for the eyes I have in my head now are not real eyes, but only crystal. I was afraid that sea water would hurt my sight, so I took out my ordinary eyes, buried them in the sand and put on these crystal ones, which I usually wear in very dusty or wet weather.”

At this the faces of the royal officers fell. How could they break the news to His Majesty and disappoint him?

Brother Bunny seemed to be really sorry for them and spoke up.

“Oh! don’t feel bad about it. If you will allow me to return to the beach, I’ll dig them up and return in time for the poultice-making,” said the rabbit.

So, getting on Dr. Turtle’s back, Brother [29]Bunny was soon out of the water and on land.

In a jiffy he jumped off, scampered away, and reached the woods, showing only his cotton tail. Soon he was out of sight.

Dr. Turtle shed tears and returned to tell how a rabbit had outwitted him. [30]

TOPKNOTS AND CROCKERY HATS

Long, long ago in China, even centuries before the great Confucius was born, there lived a wise and learned man named Kija. He was the chief counselor at court, and all honored him for his justice and goodness. He was always kind to boys and girls.

But when a great war broke out and a new line of rulers came into power, Kija declined to serve the king of the country and resolved to emigrate to the far East. There he would teach the savage people manners and refinement.

The new king was sorry to have Kija go, for he respected his character and wisdom. However he allowed five thousand of the best people, most of them Kija’s followers, to accompany their master among the Eastern savages. Many of the common folks wept when they saw the emigrants leave China the flowery country to go into the Eastern wilderness and journey to an unknown region, full of dark swamps and thick forests. Kija was going where there were no roads, farms, or houses, and the woods were full of wild beasts, especially big bears and terrible tigers that liked [31]to feed on human beings. It was even said that there were flying serpents that had wings and leopards that stood up holding lightning in their paws.

Over the great plains of Manchuria, Kija and his army of people, little folks and big ones, marched ever toward the rising sun, until they crossed the Duck Green River, which we call the Yalu. After a few days more, they came to the Great Eastern River (Ta Tong). There the land was very beautiful and Kija resolved to settle and build a city. From the tinted clouds at sunrise, rosy, golden, flushed with every shade of red, and lovely with changing colors the new country had been named Cho-sen, or Land of Morning Radiance. As the sun rose and raced toward the west, where his homeland lay, Kija welcomed the good omen as a double blessing. He saw in the calm of his first day in his adopted country a threefold pledge of continued good-will between the new kingdom and the old empire, Heaven’s favoring sign of his loyalty to the Chinese Emperor, and the surety of good-will from the spirit of the Ever White Mountain.

Having laid out for his colony a city which was to be the capital of his kingdom, Kija began to build a wall. He named the city Ping Yang, which means Northern Castle.

“But now that we have safely arrived as after [32]a voyage, the city shall be shaped like a boat,” said Kija. “Within its walls no wells shall be dug, lest this, like boring holes, should make the boat sink. Then also, on the outside, to the west, shall stand the rock pillar to which the boat city shall be forever moored.”

Kija was ably assisted by his wise men, who were skilled in literature, poetry, music, medicine and philosophy. Together they published eight great laws for the kingdom:

- 1. Agriculture for the men.

- 2. Weaving for the women.

- 3. Punishment of thieves.

- 4. Murderers to be beheaded.

- 5. All land to be divided into nine squares, the central one to be tilled in common for the benefit of the State.

- 6. Simple life for all.

- 7. The law of marriage.

- 8. Wicked people to be made slaves.

Kija laid out roads, established measures and distances and ordained the rules of politeness. He taught the savage people how to build good houses, each with roofs of thatch or tile and a kang, or warming place, by means of flues running under the floors. There was a fire at one end and a chimney at the other, so that the smoke came out of the ground half-way up the house wall. Twice a [33]day, at morning and sunset, the people fed with fuel the furnaces or cooking place in the kitchen. Then the flames, heat and smoke passed through the flues, warming the rooms. Thus the houses were made cozy and comfortable. Every day one can see the morning and the evening cloud of the kang smoke hanging over the city. It is in these flues and around the cooking pots that Tokgabi, the merry scamp, plays his most mischievous tricks. He is a sooty fellow and loves nothing better than to amuse or plague mortal men.

The people of the land were very rough and savage in these early times and being constantly given to hard fighting, murder was common. So Kija found that he must devise some way to make them peaceable. At first he tried gentle methods. He saw that the rude fellows wore their hair long, letting their locks stream out over their backs and that they were often unkempt and slovenly to the last degree. Besides they hated combs and did not like to get washed.

So Kija republished the law of Dan Kun, the spirit of the mountain, who had two topknots. He ordered that every married man should bind up his hair into a knot, or chignon, on top of his head. Thus the Korean topknot was established by law. As for the younger fellows they must plait their hair and wear it in a braid down their backs. Until a man got a wife, he was only a boy, [34]and must hold his tongue in presence of his elders. If caught wearing a topknot before he had a wife, he was punished severely.

Nevertheless the rough people mistook the good purposes of Kija. They used the topknot as a handle to catch hold of when fighting in the streets. The big, burly fellows pulled the smaller men around most cruelly. Furthermore, they were accustomed to crack each other’s skulls with clubs, so that many dead men were found in the streets. To stop these quarrels and murders, Kija invented a hat that would keep brawlers at least a yard apart.

“I’ll settle their quarrels for them, once and forever,” said Kija. “I’ll make their fun cost each man a pretty rope of cash. Every time two bullies fight, they shall have a lot of crockery to pay for.”

So Kija caused big heavy hats to be moulded of clay. These measured four feet across and were two feet high, weighing many pounds. These he had baked in ovens until they were hard as stone. They looked like big porridge bowls turned upside down.

Every fellow who had a bad temper, or was known to quarrel was compelled to wear a hat of this heavy earthenware. Whenever a crowd of men-folks got together they looked like a field of moving mushrooms.

They cracked their crockery.

[35]

When men fought they only cracked their crockery. In this way Kija easily found out who broke the law so that he could punish them. Then they had to go to the potter’s and buy new hats. This made it quite an expensive affair, for a good half year’s wages was required to pay for a hat.

Kija’s wisdom was justified. The earthenware hats proved to be a good protection to the sacred topknots and the men liked them. Quarrelsome fellows stopped pulling hair and smashing heads. It got to be the custom, instead of punching a man’s face or cracking his skull, to let off one’s bad temper in scolding and calling names, glaring frightfully, or rolling one’s eyes,—all of which of course made no blood flow. The bumpkin who could make the most frightful faces, grind his teeth most savagely, and look more like a devil than the other fellow, was reckoned the bravest and the victor.

Before many months, a street quarrel got to be a perfectly silent battle of ugly faces and terrible gestures. What at first promised to be a bloody murder usually became a noiseless duel, or a quarrel between deaf and dumb folks. This furnished violent exercise for eyes and teeth only, but it passed off like steam out of a kettle. In time a gentleness like a great calm settled over the land.

The crockery hats became all the fashion. They [36]were very popular. Even the women wanted to wear them, because they were so useful. When turned over, they served as wash-bowls and many a good housewife borrowed her husband’s second-best hat to do the family washing in. They were useful also for feed troughs and drinking basins for the horses and cattle and for donkeys to eat their beans.

The women, though not permitted to wear crockery bonnets, were pleased with the way Kija treated them. He took the clubs of the rough men, which they no longer needed, and handed them over to the wives and daughters to use in pounding the clothes on wash days and for ironing. In this way, the Korean women learned the wonderful art of putting a fine gloss on the starched clothes of the male members of the family, especially on the long white coat of the house father. Thus by changing sticks that had been used as skull-crackers into starch polishers, Kija changed also ruffians into gentlemen. Ever since, Koreans have been famous for their politeness.

Happily also, the men grew more refined in their manners and were kind to their wives and daughters, because they saw such shining clothes. When hot weather came and the gentlemen complained of the heat, and fearing that perspiration might spoil their fine clothes, Kija allowed them to make inside suits of bamboo sticks, as fine as [37]thread or wire. Thus the Korean gentleman wore his outer clothes on a frame hung from his shoulders like a hooped skirt. It seemed like taking off one’s flesh and sitting in his bones thus to wear bamboo underclothes.

By and by, as manners improved, finding garments thus made from the cane-brake so comfortable, the men gave up their heavy crockery hats. In place of these they wore “bird cages” made of horsehair over their topknots, and out-of-doors put on “roofs” of straw, reed, basket-ware, or shining black lacquered paper, according to their rank in society. Thus it came to pass that Korea is the land of hats. [38]

FANCHA AND THE MAGPIE

A thousand years ago or more, there was a tribe in the cold and desert land of the Tartars, north of Korea, which grew to be famous in that part of the world. The men let their hair grow long and then plaited it into a long braid that hung down their backs, but they shaved the front of their heads. These people were called Manchus.

Almost from babyhood they were trained to ride on horses, and in time they became such bold horsemen and warriors, that they swooped down in thousands like clouds from their mountain land into warmer and richer regions. They had terrible bows and arrows, spears and swords, and they won many victories, so that other tribes joined them. They captured great China and invaded Korea.

As long as they had been wandering tribes in the desert, they were poor and lived on plain food that the grassy plains and forests could furnish, such as nuts, herbs, the milk of mares, and mutton. Their clothes were made of the wool from their [39]own sheep. They were not proud, except of their strength, and they never asked who their grandfathers were.

But it was very different when they came to be rulers of a vast empire, rich and great like China, which had books and writing and a history of thousands of years. The elegant Chinese gentlemen and nobles used to call their conquerors the “horsey Tartars.” So they learned to wash and perfume themselves, and to care for jade, and tea, and porcelain, and silk, and other things Chinese.

Now it came to pass that when these people out of the desert sat on the thrones, and wore crowns on their heads, and dressed in satin, with jeweled robes and velvet shoes, they wanted to know who had been their ancestors long ago, and whence they came.

It would not do to believe that the fathers and mothers of so mighty a race were once common folks who in the distant deserts lived on acorns and pine nuts, with horse meat often, and mutton occasionally, and mare’s milk for dessert, or that they dressed in sheep skin and tended horses like stable boys.

Oh no! If the common folks, whom they now governed and made obey them, knew that the nobles who now lived in Peking and bullied the Koreans were once only stable and butcher boys, [40]and had no houses but lived only in tents, there would surely be trouble. These Koreans and Chinese might disobey and rebel. They might even cut off their pigtails, which the Tartars had forced them to wear, and clip their locks, like men in Europe and America. These white-faced and bearded foreigners they called “Southern Barbarians,” because their ships came up from the south by way of India.