A Hero of Romance

Richard Marsh

Transcriber's Note:

1. Page scan source:

http://books.google.com/books?id=6DAPAAAAQAAJ

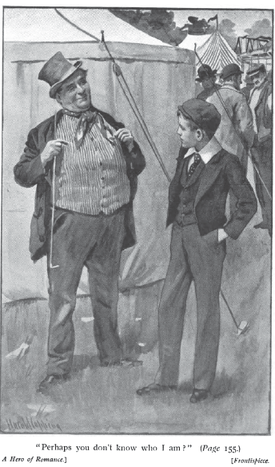

A HERO OF ROMANCE

"Perhaps you don't know who I am?"

A HERO OF ROMANCE

BY

RICHARD MARSH

Author of "The Datchel Diamonds," "The Crime and the Criminal" etc., etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY HAROLD COPPING

LONDON

WARD, LOCK & CO. LIMITED

NEW YORK AND MELBOURNE

Contents

| CHAP. | |

| I | Punishment at Mecklemburg House. |

| II | Tutor Baiting. |

| III | At Mother Huffham's. |

| IV | A Little Drive. |

| V | An Evening at Washington Villa. |

| VI | Afterwards. |

| VII | The Return of the Wanderer. |

| VIII | Preparing for Flight. |

| IX | The Start. |

| X | Another Little Drive. |

| XI | The Original Badger. |

| XII | A "Doss" House. |

| XIII | In Petersham Park. |

| XIV | In Trouble. |

| XV | Out of the Frying-pan into the Fire. |

| XVI | The Captain's Room. |

| XVII | Two Men and a Boy. |

| XVIII | The Boat-train. |

| XIX | To Jersey with a Thief. |

| XX | Exit Captain Tom. |

| XXI | The Disadvantages of not Being Able to Speak French. |

| XXII | The End of the Journey. |

| XXIII | The Land of Golden Dreams. |

Chapter I

PUNISHMENT AT MECKLEMBURG HOUSE

It was about as miserable an afternoon as one could wish to see. May is the poet's month, but there was nothing of poetry about it then. True, it was early in the month, but February never boasted weather of more unmitigated misery. At half-past two it was so dark in the schoolroom of Mecklemburg House that one could with difficulty see to read. Outside a cold drizzling rain was falling, a shrieking east wind was rattling the windows in their frames, and a sullen haze was hiding the leaden sky. As unsatisfactory a specimen of the English spring as one could very well desire.

To make things better, it was half-holiday. Not that it much mattered to the young gentleman who was seated in the schoolroom; it was no half-holiday to him. A rather tall lad, some fourteen years of age, broad and strongly built. This was Bertie Bailey.

Master Bertie Bailey was kept in; and the outrage this was to his feelings was altogether too deep for words. To keep him in!--no wonder the heavens frowned at such a crime!

Master Bertie Bailey was seated at a desk very much the worse for wear; a long desk, divided into separate compartments, which were intended to accommodate about a dozen boys. He had his arms upon the desk, his face rested on his hands, and he was staring into vacancy with an air of tragic gloom.

At the raised desk which stood in front of him before the window was seated Mr. Till. Mr. Till's general bearing and demeanour was not much more jovial than Master Bertie Bailey's; he was the tyrant usher who had kept the youthful victim in. It was with a certain grim pleasure that Bertie realized that Mr. Till's enjoyment of the keeping-in was perhaps not much more than his own.

Mr. Till had a newspaper in his hand, and had apparently read it through, advertisements and all. He looked over the top of it at Bertie.

"Don't you think you'd better get on with those lines?" he asked.

Bertie had a hundred lines of Paradise Lost to copy out. He paid no attention to the inquiry; he did not even give a sign that he was aware he had been spoken to, but continued to sit with his eyes fixed on nothing, with the same air of mysterious gloom.

"How many have you done?" Mr. Till came down to see. There was a torn copy of Milton's poems lying unopened beside Bertie on the desk; in front of him a slate which was quite clean, and no visible signs of a slate pencil. Mr. Till took up the slate and carefully examined it for anything in the shape of lines.

"So you haven't begun?--why haven't you begun?" No answer. "Do you hear me? why haven't you begun?"

Without troubling himself to alter in any way his picturesque posture, Bertie made reply,--

"I haven't got a slate pencil."

"You haven't got a slate pencil? Do you mean to tell me you've sat there for a whole hour without asking for a slate pencil? I'll soon get you one."

Mr. Till went to his desk and produced a piece about as long as his little finger, placing it in front of Bertie. Bertie eyed it from a corner of his eye.

"It isn't long enough."

"Don't tell me; take your arms off the desk and begin those lines at once."

Bertie very leisurely took his arms off the desk, and delicately lifted the piece of slate pencil.

"It wants sharpening," he said. He began to look for his knife, standing up to facilitate the search. He hunted in all his pockets, turning out the contents of each upon the desk; finally, from the labyrinthine depths of some mysterious depository in the lining of his waistcoat, he produced the ghost of an ancient pocket-knife. As though they were fragile treasures of the most priceless kind, he carefully replaced the contents of his pockets. Then, at his ease, he commenced to give an artistic point to his two-inch piece of slate pencil. Mr. Till, who had taken up a position in front of the window with his hands under his coat tails, watched the proceedings with anything but a gratified countenance.

"That will do," he grimly remarked, when Bertie had considerably reduced the original size of his piece of pencil by attempting to produce a point of needlelike fineness. Bertie wiped his knife upon his coat-sleeve, removed the pencil dust with his pocket-handkerchief, and commenced to write. Before he had got half-way through the first line a catastrophe occurred.

"I've broken the point," he observed, looking up at Mr. Till with innocence in his eyes.

"I tell you what it is," said Mr. Till, "if you don't let me have those lines in less than no time I'll double them. Do you think I'm going to stop here all the afternoon?"

"You needn't stop," suggested Bertie, looking at his broken pencil.

"I daresay!" snorted Mr. Till. The last time Bertie had been left alone in the schoolroom on the occasion of his being kept in, he had perpetrated atrocities which had made Mr. Fletcher's hair stand up on end. Mr. Fletcher was the head-master. Orders had been given that whenever Bertie was punished, somebody was to stay in with him. "Now, none of your nonsense; you go on with those lines."

Bertie bent his head with a studious air. A hideous scratching noise arose from the slate. Mr. Till clapped his hands to his ears.

"Stop that noise!"

"If you please, sir, I think this pencil scratches," Bertie said. Considering that he was holding the pencil perpendicularly, the circumstance was not surprising.

"Take my advice, Bailey, and do those lines." Advancing with an inflamed countenance, Mr. Till stood over the offending pupil. Resuming his studious posture Bertie recommenced to write. He wrote two lines, not too quickly, nor by any means too well, but still he wrote them. In the middle of the third line another catastrophe happened.

"Please, sir, I've broken the pencil right in two." It was quite unnecessary for him to say so, the fact was self-evident, though with so small a piece it had required no slight exertion of strength and some dexterous manipulation to accomplish the feat. The answer was a box on the ears.

"What did you do that for?" asked Bertie, rising from his seat, and rubbing the injured portion with his hand.

Now it was distinctly understood that Mecklemburg House Collegiate School was conducted on the principle of no corporal punishment. It was a prominent line in the prospectus. "Under no circumstances is corporal punishment administered." As a rule the principle was consistently carried out to its legitimate conclusion, not with the completest satisfaction to every one concerned. Yet Mr. Fletcher, one of the most longsuffering of men, and by no means the strictest disciplinarian conceivable, had been more than once roused into administering short and sharp justice upon refractory youth. But what was excusable in Mr. Fletcher was not to be dreamed of in the philosophy of anybody else. For an assistant-master to strike a pupil was a crime; and Mr. Till knew it, and Master Bertie Bailey knew it too.

"What did you do that for?" repeated Bertie.

Mr. Till was crimson. He was not a hasty tempered man, but to-day Master Bertie Bailey had been a burden greater than he could bear. Yet he had very literally made a false stroke, and Bertie was just the young gentleman to make the most of it.

"If I were to tell Mr. Fletcher, he'd turn you off," said Bertie. "He turned Mr. Knox off for hitting Harry Goddard."

Harry Goddard's only relation was a maiden aunt, and this maiden aunt had peculiar opinions. In her opinion for anybody to lay a punitory hand upon her nephew was to commit an act tantamount to sacrilege. Harry had had a little difference with Emmett minor, and had borne away the blushing honours of a bloody nose and a black eye with considerable sang-froid; but when Mr. Knox resented his filling his best hat with half-melted snow by presenting him with two or three smart taps upon a particular portion of his frame, Harry wrote home to his aunt to complain of the indignity he had endured. The result was that the ancient spinster at once removed the outraged youth from the sanguinary precincts of Mecklemburg House, and that Mr. Fletcher dismissed the offending usher.

As Mr. Till stood eyeing his refractory pupil, all this came forcibly to his mind. He knew something more than Bertie did; he knew that when Mr. Fletcher, smarting at the loss of a remunerative pupil, had made short work of his unfortunate assistant, he had also taken advantage of the occasion to call Mr. Till into his magisterial presence, and to then and there inform him, that should he at any time lay his hand upon a pupil, under any provocation of any kind whatever, the result would be that Mr. Knox's case would be taken as a precedent, and he would be instantaneously dismissed.

And now he had struck Bertie, and here was Bertie threatening to inform his employer of what he had done.

"If you don't let me off these lines," said Bertie, pursuing his advantage, "I'll tell Mr. Fletcher as soon as he comes home, you see if I don't."

Mecklemburg House Collegiate School was not a scholastic establishment of any particular eminence; indeed, whatever eminence it possessed was of an unsavoury kind. Nor was the position of its assistant-master at all an enviable one. There was the senior assistant, Mr. Till, and there was the junior, Mr. Shane. Mr. Till received £30 a year, and Mr. Shane, a meek, melancholy youth of about seventeen, received sixteen. Nor could the duties of either of these gentlemen be considered light. But if the pay was small and the work large, the intellectual qualifications required were by no means of an unreasonable kind. Establishments of the Mecklemburg House type are fading fast away. English private schools are improving every day. Mr. Till, conscious of his deficiencies, was only too well aware that if he lost his present situation, another would be hard to find. So, in the face of Bertie's threat, he temporized.

"I didn't mean to hit you! You shouldn't exasperate me!"

Bertie looked him up and down. If ever there was a young gentleman who needed the guidance of a strong hand, Bertie was he. He was not a naturally bad boy,--few boys are,--but he hated work, and he scorned authority. All means were justifiable which enabled him to shirk the one and defy the other. He was just one of those boys who might become bad if he was not brought to realize the difference between good and evil, right and wrong. And it would need sharp discipline to bring him to such knowledge.

He had a supreme contempt for Mr. Till. All the boys had. The only person they despised more was Mr. Shane. It was the natural result of the system pursued at Mecklemburg House that the masters were looked upon by their pupils as quite unworthy their serious attention.

Bertie had had about a dozen impositions inflicted on him even within the last days. He had not done one of them. He never did do them. None of the boys ever did do impositions set them by anybody but Mr. Fletcher. They did not by any means make a point of doing his.

"You will do me fifty lines," Mr. Till would say to half a dozen boys half a dozen times over in the course of a single morning. He spoke to the wind; no one ever did them, no one would have been so much surprised as Mr. Till if they had been done.

On the present occasion Mr. Fletcher had gone to town on business, and Mr. Till had been left in supreme authority. Bailey had signalised the occasion by behaving in a manner so outrageous that, if any semblance of authority was to be kept at all, it was altogether impossible to let him go scot free. As it was a half-holiday, Mr. Till had announced his unalterable resolve that Bertie should copy out a hundred lines of Paradise Lost, and that he should not leave the schoolroom till he had written them.

The result so far had not been satisfactory. He had been in the schoolroom considerably over an hour; he had written not quite three lines, and here he was telling Mr. Till that if he did not let him off entirely he would turn the tables on his master, and make matters unpleasant for him. It looked as though Bertie would win the game.

Having taken the tutor's mental measure, he thrust his hands into his trousers pockets, and coolly seated himself upon the desk. Then he made the following observation,--

"I tell you what it is, old Till, I don't care a snap for you."

Mr. Till simply glared. He realized, not for the first time, that the pupil was too much for the master. Bertie continued,--

"My father always pays regularly in advance. If I wrote home and told him that you'd hit me, for nothing"--Bertie paused and fixed his stony gaze on Mr. Till--"he'd take me home at once, and then what would Fletcher say?" Bertie paused again, and pointed his thumb over his left shoulder. "He'd say, 'Walk it'!"

This was one way of putting it. Though Mr. Bailey was by no means such a foolish person as his son suggested. He was very much unlike Harry Goddard's maiden aunt. Had Bertie written home any such letter of complaint--which, by the way, he was far too wise to have dreamed of doing--the consequences would in all probability have been the worse for him. The father knew his son too well to be caught with chaff. Unfortunately, Mr. Till did not know this; he had Mr. Knox's fate before his eyes.

"You'd better let me off these lines," pursued the inexorable Bertie; "you'd better, you know."

"You're an impudent young----" But Bertie interrupted him.

"Now don't call me names, or I'll tell Fletcher. He only said the other day that all his pupils were to be treated like young gentlemen."

"Young gentlemen!" snorted Mr. Till with scorn.

"Yes, young gentlemen. And don't you say we're not young gentlemen, because Mecklemburg House Collegiate School is an establishment for young gentlemen." And Bertie grinned. "You'd better let me off these lines, you know."

"You know I never hurt you; you shouldn't exasperate me; you're the most exasperating boy I ever knew; there's absolutely no bearing with your insolence! You'd try the patience of a saint."

"I shouldn't be surprised if I was deaf for a week." He rubbed the injured part reflectively. "I've heard Fletcher say it's dangerous to hit a fellow on the ear. You'd better let me off those lines, you know."

Mr. Till, fidgeting about the room, suddenly burst into eloquence. "I wonder if it's any use appealing to your better nature? They say boys have a better nature, though I never remember to have seen much of it. What pleasure do you find in making my life unbearable? What have I ever done to you that you should try to drive me mad? Are you naturally cruel? My sole aim is for your future welfare! Your sole aim is for my ruin!"

Bertie continued to rub his ear.

"Bailey, if I let you off these lines will you promise to try to give me less cause to punish you?"

"You can't help letting me off them anyhow," said Bertie.

"Can't I? I suppose, young gentleman, you think you're getting the best of me?"

"I know I am," said Bertie.

"Oh, you know you are! Then let me do my best to relieve you of that delusion. Shall I tell you what you are doing? You're doing your best to sow the seeds of a shameful manhood and a wasted life; if you don't take care you'll reap the harvest by-and-by! It isn't only that you're refusing to avail yourself of opportunities of education, you're doing yourself much greater harm than that. You think you're getting the best of me; but shall I tell you what's getting the best of you?--a mean, cruel, cowardly spirit, which will be to you a sterner master than ever I have been. You think yourself brave because you jeer and mock at me, and flout all my commands! Why, my boy, were I better circumstanced, and free to act upon my own discretion, you would tremble in your shoes! The very fact of your permitting yourself to threaten me, on account of punishment which you know was perfectly well deserved, shows what sort of boy you are!"

Bertie's only comment was, "You had better let me off those lines."

"I will let you off the lines!"

Bertie sprang to his feet, and began to put slate and book away with abundance of clatter.

"Stay one moment--leave those things alone! It is not the punishment which degrades a man, Bailey; it is the thing of which he has been guilty. I cannot degrade you; it is yourself you are degrading. Take my advice, turn over a new leaf, learn not to take advantage of a man whose only offence is that he does his best to do you good; don't think yourself brave because you venture to attack where defence is impossible; and, above all, don't pride yourself on taking your pigs to a bad market. You are so foolish as to think yourself clever because you throw away all your best chances, and get absolutely worse than nothing in return. Bailey, get your Bible, and look for a verse which runs something like this, 'Cast your bread upon the waters, and you shall find it after many days.' Now you can go."

And Bertie went; and, being in the safe neighbourhood of the door, he put his fingers to his nose; by which Mr. Till knew, not for the first time, that he had spoken in vain.

Chapter II

TUTOR BAITING

There were twenty-seven boys at Mecklemburg House; and even this small number bade fair to decrease. Last term there had been thirty-three; the term before there had been forty. Within quite recent years considerably over a hundred boys had occupied the draughty dormitories of the great old red-brick house.

But the glory was departing. It is odd how little our fathers and our grandfathers in general knew or cared about the science of education. Boys were pitchforked into schools which had absolutely nothing to recommend them except a flourishing prospectus; schools in which nothing was taught, in which the physique of the lads was neglected, and in which their moral nature was treated as a thing which had no existence. A large number of "schoolmasters" had no more idea of true education than they had of flying. They were speculators pure and simple, and they treated their boys as goods out of which they were to screw as much money as they possibly could, and in the shortest possible space of time.

Mecklemburg House Collegiate School was a case in point. It had been a school ever since the first of the Georges; and it is, perhaps, not too much to say, that out of the large number of boys who had been educated beneath its roof, not one of them had received a wholesome education. Yet it had always been a paying property. More than one of its principals had retired with a comfortable competency. Certainly the number of its pupils had never stood at such a low ebb as at the time of which we tell. Why the number should be so uncomfortably low was a mystery to its present principal, Beauclerk Fletcher. The place had belonged to his father, and his father had always found it bring something more than daily bread. But even daily bread was beginning to fail with Beauclerk Fletcher. Twenty-seven pupils at such a place as Mecklemburg House! and the majority of them upon "reduced terms"! Mr. Fletcher, never the most enterprising of men, was beginning to be overwhelmed beneath an avalanche of debt, and to feel that the fight was beyond his strength.

A great, old, rambling red-brick house, about equi-distant from Cobham, Byfleet, Weybridge--all towns in Surrey--lying in about the middle of the irregular square which those four towns form, the house carried the story of its decaying glories upon its countenance. Those Georgian houses were solid structures, and the mere fabric was in about as good a condition as it had ever been! but in the exterior of the building the change was sadly for the worse. Many of the rooms were unoccupied, panes were broken in the windows, curtains were wanting, the windows looked as though they were seldom or never cleaned. The whole place looked as though it were neglected, which indeed it was. Slates were off the roof, waste water pipes hung loose and rattled in every passing breeze. As to the paved courtyard in front, grass and weeds and moss almost hid the original stones. Mr. Fletcher was only too conscious of the story all this told; but to put things shipshape and neat, and to keep them so, required far more money than he had to spend; so he only groaned at each new evidence of ruin and decay.

The internal arrangements, the domestic economy, the whole system of education, everything in connection with Mecklemburg House was in the same state of decrepitude and age--worn-out traditions rather than living things. And Mr. Fletcher was very far from being the man to breathe life into the dead bones and bid them live. The struggle was beyond his strength.

There is no creature in God's world sharper than the average boy, no one quicker to understand the strength of the hand which holds him. The youngest pupil at Mecklemburg House was perfectly aware that the school was a "duffing" school, that Mr. Fletcher was a "duffing" principal, and that everything about the place was "duffing" altogether. Only let a boy have this opinion about his school, and, so far as any benefit is concerned which he is likely to derive from his sojourn there, he might almost as profitably be transported to the Cannibal Islands.

On the half-holiday on which our story opens, the pupils of Mecklemburg House were disporting themselves in what was called the playroom. Formerly, in its prosperous days, the room had been used as a second schoolroom, the one at present used for that purpose being not nearly large enough to contain the pupils. But those days were gone; at present, so far from being overcrowded, the room looked empty, and could have with ease accommodated twice the whole number of pupils which the school contained. So what was once the schoolroom was called the playroom instead.

"Stupid nonsense! keeping a fellow in because it rains!" said Charles Griffin, looking through the dirty window at the grimy world without.

"It doesn't rain," declared Dick Ellis. "Call this rain! I say, Mr. Shane, can't we go down to the village? I want to get something for this cough of mine; it's frightful." And with some difficulty Dick managed to produce a sepulchral cough from somewhere about the region of his boots.

"Mrs. Fletcher says you are not to go out while it rains," answered Mr. Shane in his mildest possible manner.

"Mrs. Fletcher!" grunted Dick. At Mecklemburg House the grey mare was the better horse. If Mr. Fletcher was not an ideal head-master, Mrs. Fletcher was emphatically head-mistress.

That half-holiday was a pleasant one for Mr. Shane. It was a rule that the boys were never to be left alone. If they were out a master was to go with them, if they were in a master was to supervise. So, as Mr. Till was engaged with the refractory Bertie, Mr. Shane was in charge of the play-room.

In charge, literally, and in terror, too. For it may be maintained without the slightest exaggeration, that he was much more afraid of the boys than the boys of him. On what principle of selection Mr. Fletcher chose his assistant-masters it is difficult to say; but whatever else Mr. Shane was, a disciplinarian he certainly was not. He was the mildest-mannered young man conceivable, awkward, shy, slight, thin, not bad-looking, with a faint, watery smile, which at times gave quite a ghastly appearance to his countenance, and a deprecatory manner which seemed to say that you had only to let him alone to earn his eternal gratitude. But the boys never did let him alone, never. By day and night, awake and sleeping, they did their best to make his life a continual misery.

"If we can't go out," suggests Griffin, "I vote we have a lark with Shane."

Mr. Shane smiled, by no means jovially.

"You mustn't make a noise," he murmured, in that soft, almost effeminate voice of his. "Mrs. Fletcher particularly said you were not to make a noise."

"Right you are. I say, Shane, you stand against the wall, and let's shy things at you." This from Griffin.

"You're not to throw things about," said Mr. Shane.

"Then what are we to do, that's what I want to know? It seems to me we're not to do anything. I never saw such a beastly hole! I say, Shane, let half of us get hold of one of your arms, and the other half of the other, and have a pull at you--tug-of-war, you know. We won't make a noise."

Mr. Shane did not seem to consider the proposal tempting. He was seated in the window, and had a book on his knees which he wanted to read. Not a work of light literature, but a German grammar. It was the dream of his life to prepare himself for matriculation at the London University. This undersized youth was a student born; he had company which never failed him, a company of dreams. He dreamed of a future in which he was a scholar of renown; and in every moment he could steal he strove to bring himself a step nearer to the realization of his dreams.

"Get up, Shane!--what's that old book you've got?" Griffin made a snatch at the grammar. Mr. Shane jealously put it behind his back. Books were in his eyes things too precious to be roughly handled. "Come and have a lark; what an old mope you are!" Griffin caught him by the arm and swung him round into the room; the boy was as tall, and probably as strong as the usher.

The boys were chiefly engaged in doing nothing; nobody ever did do much in that establishment. If a boy had a hobby it was laughed out of him. Literature was at a discount: Spring-Heeled Jack and The Knights of the Road were the sort of works chiefly in request. There was no school library, none of the boys seemed to have any books of their own. There was neither cricket nor football, no healthy games of any sort. Even in the playground the principal occupation was loafing, with a little occasional bullying thrown in. Mr. Fletcher was too immersed in the troubles of pounds, shillings, and pence to have any time to spare for the amusements of the boys. Mr. Till was not athletic. Mr. Shane still less so. On fine afternoons the boys were packed off with the ushers for a walk, but no more spiritless expeditions could be imagined than the walks at Mecklemburg House. The result was that the youngsters' life was a wearisome monotony, and they were in perpetual mischief for sheer want of anything else to do. And mischief so often took the shape of cruelty.

Charlie Griffin swung Mr. Shane out into the middle of the room, and immediately one boy after another came stealing up to him.

"I say, Shane, let's play roley-poley with you," said Brown major. Some one in the rear threw a hard pellet of brown paper, which struck Mr. Shane smartly on the head. He winced.

"Who threw that?" asked Griffin. "I say, Shane, why don't you whack him? If I were a man I wouldn't let little boys throw things at me; you are a man, aren't you, Shane?" He gave another jerk to the arm which he still held.

"You're not to pull my arm, Griffin; you hurt me. I wonder why you boys can't leave me alone."

"Go along! not really! We're only having a game, Shane; we're not in school, you know. What shall we do with him, you fellows? I vote we tie him in a chair, and stick needles and pins into him; he's sure to like that--he's such a jolly old fellow, Shane is."

"Why don't you let us go out?" asked Ellis.

"You know Mrs. Fletcher said you were not to go."

"Oh, bother Mrs. Fletcher! what's that got to do with it? We won't tell her if you let us go."

Mr. Shane sighed. Had it rested with him he would have been only too glad to let them go. Two or three hours of his own company would have been like a glimpse of paradise. But there was Mrs. Fletcher; she was a lady whose indignation was not to be lightly faced.

"If you won't let us go," said Ellis, "we'll make it hot for you. Do you think we're a lot of babies, to be melted by a drop of rain?"

"You know it's no use asking me. Mrs. Fletcher said you were not to go out if it rained, and it is raining."

"It's not raining," boldly declared Griffin. "Call this rain! why, it's not enough to wet a cat! I never saw such a molly-coddle set-out. I go out when I'm at home if it pours cats and dogs; nobody minds; why should they? Come on, Shane, let's go, there's a trump; we won't sneak, and we'll be back in half a jiff.

"I wish you would let me alone," said Mr. Shane. Somebody snatched his book out of his hand. He turned swiftly to recover it, but the captor was out of reach. "Give me my book!" he cried. "How dare you take my book!"

"Here's a lark! catch hold, Griffin." Mr. Shane, hurrying to recover his treasure, saw it dexterously thrown above his reach into the hands of Charlie Griffin.

"Give me my book, Griffin!" And he made a rush at Griffin.

"Catch, boys!" Griffin threw the book to some one else before Mr. Shane could reach him. It was thrown from one to the other, from end to end of the room, probably not being improved by the way in which it was handled.

The usher stood in the midst of the laughing boys, a picture of helplessness. The grammar had cost him half a crown at a second-hand bookstall. Half a crown represented to him a handsome sum. There were many claims upon his sixteen pounds a year; he had to think once, and twice, and thrice before he spent half a crown upon a book. His books were to him his children. In those dreams of future glory his books were his constant companions, his open sesame, his royal road to fame; with their aid he could do so much, without their aid so little. So now and then he ventured to spend half a crown upon a volume which he wanted.

The grammar, being badly aimed, fell just in front of him. He made a dash at it. Some one gave him a push and he fell sprawling on the floor; but he seized the book with his left hand. Griffin, falling on it tooth and nail, caught hold of it before he could secure it from danger. There was a rush of half a dozen. Every one wanted a finger in the pie. The grammar was clutched by half a dozen hands at once. The back was rent off, leaves pulled out, the book was torn to shreds. Mr. Shane lay on the floor, with the ruins of his grammar in his hands.

Just then Bertie Bailey entered the room, victorious from his contest with Mr. Till. A shout of welcome greeted him.

"Hullo, Bailey! have you done the lines?"

Bertie, a deliberate youth as a rule, took his time to answer. He surveyed the scene, then he put his fingers to his nose, repeating the gesture with which he had retreated from Mr. Till.

"Catch me at it!--think I'm a silly?" Then he put his hands into his pockets, and slouched into the centre of the room. The boys crowded round him.

"Did he let you off?" asked Griffin.

"Of course he let me off; I made him: he knew better than to try to make me do his lines."

Then he told the story; the boys laughed. The way in which the ushers were compelled to stultify themselves was a standing joke at Mecklemburg House. That Mr. Till should have been forced to eat his own words, and to let insubordination go unpunished, was a humorous idea to them.

Mr. Shane still remained upon the floor. He was engaged in gathering together the remnants of his grammar. Perhaps a pot of paste, with patient manipulation, might restore it yet. He would give himself a great deal of labour to avoid the expenditure of another half-crown; perhaps he had not another half-crown to spend.

"What's the row?" asked Bertie, seeing Mr. Shane engaged in gathering up the fragmentary leaves. They told him.

"I'm going out," said Bailey, "and I should like to see anybody stop me. I say, Mr. Shane, I want to go down to the village."

Mr. Shane repeated his stock phrase.

"Mrs. Fletcher said no one was to go out while it rained." He had collected all the remnants of his grammar, and was rising with them in his hand.

"Give me hold!" exclaimed Bertie; and he snatched what was left of the book out of the usher's hands.

"Bailey!" cried Mr. Shane.

"Look here, I want to go down to the village. I suppose I may, mayn't I?"

"Mrs. Fletcher said no one was to go out if it rained," stammered Mr. Shane.

"If you don't let me go, I'll burn this rubbish!" Bertie flourished the ruined grammar in the tutor's face. Mr. Shane made a dart to recover his property; but Bertie was too quick for him, and sprang aside beyond his reach. It is not improbable that if it had come to a tussle Mr. Shane would have got the worst of it.

"Who's got a match?" asked Bertie. Some one produced half a dozen. "Will you let me go?"

"Don't burn it," said Mr. Shane. "It cost me half a crown; I only bought it last week."

"Then let me go."

"What'll Mrs. Fletcher say?"

"How's she to know unless you tell her? I'll be back before tea. I don't care if it cost you a hundred half-crowns, I'll burn it. Make up your mind. Is it going to cost you half a crown to keep me in?"

Bertie struck a match. Mr. Shane attempted to rush forward to put it out, but some of the boys held him back. His heart went out to his book as though it were a child.

"If I let you go, you promise me to be back within half an hour? I don't know what Mrs. Fletcher will say if she should hear of it;--and don't get wet."

"I'll promise you fast enough. Mrs. Fletcher won't hear of it; and what if she does? She can't eat you. You needn't be afraid of my getting wet."

"I shan't let anybody else go."

"Oh yes, you will! You'll let Griffin and Ellis go; you don't think I'm going all that way alone?"

"And me!" cried Edgar Wheeler. Pretty nearly all the other boys joined him in the cry.

"I am not going to have all you fellows coming with me," announced Bertie. "Wheeler can come; but as for the rest of you, you can stay at home and go to bed--that's the best place for little chaps like you. Now then, Shane, look alive; is it going to cost you half a crown, or isn't it?"

Mr. Shane sighed. If ever there was a case of a round peg in a square hole, Mr. Shane's position at Mecklemburg House was a case in point. The youth, for he was but a youth, was a good youth; he had an earnest, honest, practical belief in God; but surely God never intended him for an assistant-master. Perhaps in the years to come he might drift into the place which had been prepared for him in the world, but it was difficult to believe that he was in it now. A studious dreamer, who did nothing but dream and study, he would have been no more out of his element in a bear garden than in the extremely difficult and eminently unsatisfactory position which he was supposed--it was veritable supposition--to fill at Mecklemburg House.

"How many of you want to go?"

"There's me,"--Bertie was not the boy to take the bottom seat--"and Griffin, and Ellis, and Wheeler, that's all. Now what is the good of keeping messing about like this?"

"You're sure you won't be more than half an hour?"

"Oh, sure as sticks."

"And what shall I say to Mrs. Fletcher if she finds out? You're sure to lay all the blame on me." Mr. Shane had a prophetic eye.

"Say you thought it didn't rain."

"I don't think it does rain much." Mr. Shane looked out of the window, and salved his conscience with the thought. "Well, if you're quite sure you won't get wet, and you won't be more than half an hour--you--can--go." The latter three words came out, as it were, edgeways and with difficulty from the speaker's mouth, as if even he found the humiliation of his attitude difficult to swallow.

"Come along, boys!--here's your old book!" Bertie flung the grammar into the air, the leaves went flying in all directions, the four boys went clattering out of the room with noise enough for twenty, and Mr. Shane was left to recover his dignity and collect the scattered volume at his leisure.

But Nemesis awaited him. No sooner had the conquering heroes disappeared than an urchin, not more than eight or nine years of age, catching up one of the precious leaves, exclaimed,--

"Let's tear the thing to pieces!" The speaker was little Willie Seymour, Bertie Bailey's cousin. It was his first term at school, but he already bade fair to do credit to the system of education pursued at Mecklemburg House.

"Right you are, youngster," said Fred Philpotts, an elder boy. "It's a burning shame to let them go and keep us in. Let's tear it all to pieces."

And they did. There was a sudden raid upon the scattered leaves; at the mercy of twenty pairs of mischievous hands, they were soon reduced to atoms so minute as to be altogether beyond the hope of any possible recovery. Nothing short of a miracle could make those tiny scraps of printed paper into a book again. And seeing it was so Mr. Shane leaned his head against the window-pane and cried.

Chapter III

AT MOTHER HUFFHAM'S

It was only when Bailey and his friends were away from the house that it occurred to them to consider what it was they had come out for. They slunk across the grass-grown courtyard, keeping as close to the wall as possible, to avoid the lynx-eyes of Mrs. Fletcher. That lady was the only person in Mecklemburg House whose authority was not entirely contemned. Let who would be master, she would be mistress; and she had a way of impressing that fact upon those around her which made it quite impossible for those who came within reach of her influence to avoid respecting.

It was truly miserable weather. Any one but a schoolboy would have been only too happy to have had a roof of any kind to shelter him, but schoolboys are peculiar. It was one of those damp mists which not only penetrate through the thickest clothing, and soak one to the skin, but which render it difficult to see twenty yards in front of one, even in the middle of the day. The day was drawing in; ere long the lamps would be lighted; the world was already enshrouded in funeral gloom. Not a pleasant afternoon to choose for an expedition to nowhere in particular, in quest of nothing at all.

The boys slunk through the sodden mist, hands in their pockets, coat collars turned up about their ears, hats rammed down over their eyes, looking anything but a cheerful company. Griffin asked a question.

"I say, Bailey, where are you going?"

"To the village."

"What are you going to the village for?" This from Ellis.

"For what I am."

After this short specimen of convivial conversation the four trudged on. Alas for their promise to Mr. Shane! The wet was already dripping off their hats, and splashings of mud were ascending up the legs of their trousers to about the middle of their back. In a minute or two Wheeler began again.

"Have you got any money?"

Bertie pulled up short. "Have you?" he asked.

"I've got sevenpence."

"Then lend me half?"

"Lend me a penny? I'll pay you next week; honour bright, I will," said Ellis.

Griffin was more concise. "Lend me twopence?" he asked.

Wheeler looked unhappy. It appeared that he was the only capitalist among the four, and under the circumstances he did not feel exactly proud of the position. Although sevenpence might do very well for one, it would not be improved by quartering.

"Yes, I know, I daresay," he grumbled. "You're very fond of borrowing, but you're not so fond of paying back again." He trudged on stolidly.

Bailey caught him by the arm. "You don't mean that you're not going to lend me anything, after my asking for you to come out with me, and all?"

"I'll lend you twopence."

"Twopence! What's twopence?"

"It's all you'll get; you can have it or lump it, I don't care; I'm not dead nuts on lending you anything." Wheeler was a little wiry-built boy, and when he meant a thing very much indeed he had an almost terrier-like habit of snapping his jaws--he snapped them now. Bailey trudged by his side with an air of dudgeon; he probably reflected that, after all, twopence was better than nothing. But Ellis and Griffin had their claims to urge. They apparently did not contemplate with pleasure the prospect of tramping to and from the village for the sake of the exercise alone. Ellis began,--

"I say, old fellow, you'll lend me a penny, won't you? I'm always game for lending you."

"Look here, I tell you what it is, I won't lend you a blessed farthing! It's like your cheek to ask me; you owe me ninepence from last term."

"But I expect a letter from home in the morning with some money in it. I'll pay you the ninepence with threepence interest--I'll pay you eighteenpence--you see if I don't. And if you'll lend me a penny now I'll give you twopence for it in the morning. Do now, there's a good fellow, Wheeler; honour bright, I will."

For answer Wheeler put his finger to his eye and raised the eyelid. "See any green in my eye?" he said.

"You're a selfish beast!" replied his friend. And so the four trudged on. Then Griffin made his attempt.

"I'll let you have that knife, Wheeler, if you like."

"I don't want the knife."

"You can have it for threepence."

"I don't want it for threepence."

"You offered me fourpence for it yesterday."

"I've changed my mind."

Charlie pondered the matter in his mind. They were about half-way to their destination, and already bore a closer resemblance to drowned rats than living schoolboys. By the time they had gone there and back again, it would be possible to wring the water out of their clothes; what Mrs. Fletcher would have to say remained to be seen. After they had gone a few yards further, and paddled through about half a dozen more puddles, Charlie began again.

"I'll let you have it for twopence."

"I don't want it for twopence."

"It's a good knife." No answer. "It cost a shilling." Still no answer. "There's only one blade broken." Still no reply. "And that's only got a bit off near the point." Still silence. "It's a jolly good knife." Then, with a groan, "I'll let you have it for a penny."

"I wouldn't give you a smack in the eye for it."

After receiving this truly elegant and generous reply, Griffin subsided into speechless misery. It is not improbable that, so far as he was himself concerned, he began to think that the expedition was a failure.

In silence they reached the village. It was not a village of portentous magnitude, since it only contained thirteen cottages and one shop, the shop being the smallest cottage in the place. The only point in its favour was that it was the nearest commercial establishment to Mecklemburg House. The proprietor was a Mrs. Huffham, an ancient lady, with a very bad temper, and a still worse reputation--among the boys--for honesty in the direction of weights and measures. It must be conceded that they could have had no worse opinion of her than she had of them.

"Them young warmints, if they wants to buy a thing they wants ninety ounces to the pound, and if they wants to pay for it, they wants you to take eightpence for a shilling--oh, I knows 'em!" So Mrs. Huffham declared.

At the door of this emporium parley was held. Ellis suddenly remembered something.

"I say, I owe old Mother Huffham two-and-three." So far as the gathering mist and the soaking rain enabled one to see, Dick's countenance wore a lugubrious expression.

"Well, what of that?"

"Well"--Dick Ellis hesitated--"so long as that brute Stephen isn't about the place I don't mind. He called out after me the other day, that if I didn't pay he'd take the change out of me some other way."

The Stephen referred to was Mrs. Huffham's grandson, a stalwart young fellow of twenty-one or two, who drove the carrier's cart to Kingston and back. His ideas on pecuniary obligations were primitive. Having learned from experience that it was vain to expect Mr. Fletcher to pay his pupils' debts at the village shop, he had an uncomfortable way of taking it out of refractory debtors in the shape of personal chastisement. Endless disputes had arisen in consequence. Mr. Fletcher had on more than one occasion threatened the summary Stephen with the terrors of the law; but Stephen had snapped his fingers at Mr. Fletcher, advising him to pay his own debts, lest worse things happened to him. Then Mr. Fletcher had forbidden Mrs. Huffham to give credit to the boys; but Mrs. Huffham was an obstinate old lady, and treated the headmaster with no more deference than her grandson. Finally, Mr. Fletcher had forbidden the boys to deal with Mrs. Huffham; but in spite of his prohibition an active commerce was carried on, and on more than one occasion the irate Stephen had been moved to violence.

"You should have stopped at home," was Wheeler's not unreasonable reply to Dick's confession. "I don't owe her anything. I don't see what you wanted to come for, anyhow, if you haven't got any money and you owe her two-and-three."

And turning the handle of the rickety door he entered Mrs. Huffham's famed establishment. Bailey, rich in the possession of a prospective loan of twopence, and Charlie Griffin followed close upon his heels. After hesitating for a moment Ellis went in too. To remain shivering outside would have been such a lame conclusion to a not otherwise too satisfactory expedition, that it seemed to him like the last straw on the camel's back. Besides, it was quite on the cards that the impetuous Stephen would be engaged in his carrier's work, and be pleasantly conspicuous by his absence from home.

The interior of the shop was pitchy dark. The little light which remained without declined to penetrate through the small lozenge-shaped windowpanes. Mrs. Huffham's lamp was not yet lit, and the obscurity was increased by the quantity of goods, of almost every description, which crowded to overflowing the tiny shop. No one came.

"Let's nick something," suggested the virtuously minded Griffin. Ellis acted on the hint.

"I'm not going there and back for nothing, I can tell you."

On a little shelf at the side of the shop stood certain bottles of sweets. Dick reached up to get one down. At that moment Wheeler gave him a jerk with his arm. Ellis, catching at the shelf to steady himself, brought down shelf, bottles and all, with a crash upon a counter.

"Thieves!" cried a voice within. "Thieves!" and Mrs. Huffham came clattering into the shop, out of some inner sanctum, with considerable haste for one of her mature years. "Thieves!"

For some moments the old lady's eyes could see nothing in the darkness of the shop. She stood, half in, half out, peering forward, where the boys could just see her dimly in the shadow. They, deeming discretion to be the better part of valour, and not knowing what damage they might not have done, stood still as mice. Their first impulse was to turn and flee, and Griffin was just feeling for the handle of the door, preparatory to making a bolt for it, when heavy footsteps were heard approaching outside, and the door was flung open with a force which all but threw Griffin back upon his friends.

"Hullo!" said a voice; "is anybody in there?"

It was Stephen Huffham. With all their hearts the boys wished they had respected authority and listened to Mr. Shane! There was a coolness and promptness about Stephen Huffham's method of taking the law into his own hands upon emergency which formed the basis of many a tale of terror to which they had listened when tucked between the sheets at night in bed.

Mr. Huffham waited for no reply to his question, but he laid an iron hand upon Griffin's shoulder and dragged him out into the light.

"Come out of that! Oh, it's you, is it?" Charlie was gifted with considerable powers of denial, but he found it quite beyond his power to deny Mr. Huffham's assertion then. "Oh, there's some more of you, are there? How many of you boys are there inside here?"

"They've been a-thieving the things!" came in Mrs. Huffham's shrill treble from the back of the shop.

"Oh, they have, have they? We'll soon see about that. Unless I'm blinder than I used to be, there's young Ellis over there, with whom I've promised to have a word of a sort before to-day. You bring a light, granny, and look alive; don't keep these young gentlemen waiting, not by no manner of means."

Mrs. Huffham retreated to her parlour, and presently re-appeared with a lighted lamp in her hand. This, with great deliberation, for her old bones were stiff, and rheumatism forbade anything like undue haste, she hung upon a nail, in such a position that its not too powerful light shed as great an illumination as possible upon the contents of her shop. Far too powerful an illumination to suit the boys, for it brought into undue prominence the damage wrought by Ellis and his friend. They eyed the ruins, and Mrs. Huffham eyed them, and Mr. Stephen Huffham eyed them too. The old lady's feelings at the sight were for a moment too deep for words, but Mr. Stephen Huffham soon found speech.

"Who did this?" he asked; and there was something in the tone of the inquiry which grated on his hearers' ears.

Had Dick Ellis and his friend deliberately planned to do as much mischief as possible in the shortest possible space of time, they could scarcely have succeeded better. Three or four of the bottles were broken to pieces, and in their fall they had fallen on a little glass case, the chief pride and ornament of Mrs. Huffham's shop, which was divided into compartments, in one of which were cigars, in another reels of cotton and hanks of thread, and in a third such trifles as packets of hair-pins, pots of pomade, note-paper and envelopes, and a variety of articles which might be classified under the generic name of "fancy goods." The glass in this case was damaged beyond repair; the sweets from the broken bottles had got inside, and had become mixed with the cigars, and the paper, and the hair-pins, and the pomade, and the rest of the varied contents.

Mr. Stephen Huffman not finding himself favoured with an immediate reply to his inquiry, repeated it.

"Who did this? Did you do this?" And he gave Charlie Griffin a shake which made him feel as though he were being shaken not only upside down, but inside out.

"No-o-o!" said Charlie, as loudly as he was able with Mr. Stephen Huffman shaking him as a terrier shakes a rat. "I-I-I didn't! Le-e-eave me alone!"

"I'll leave you alone fast enough! I'll leave the lot of you alone when I've taken all the skin off your bodies! Did you do this?" And Mr. Stephen Huffham transferred his attention to Bailey.

"No!" roared Bertie, before Huffman had time to get him fairly in his grasp. Mr. Huffman held him at arm's length, and looked him full in the face with an intensity of scrutiny which Bertie by no means relished.

"I suppose none of you did do it; nobody ever does do these sort of things, so far as I can make out. It was accidental; it always is."

His voice had been so far, if not conciliatory, at least not unduly elevated. But suddenly he turned upon Ellis with a roar which was not unlike the bellow of a bull. "Did you do it?"

Ellis started as though he had received an electric shock.

"No-o!" he gasped. "It was Wheeler!"

"Oh, it was Wheeler, was it?"

"It wasn't me," said Wheeler.

"Oh, it wasn't you? Who was it, then? That's what I want to know; who was it, then?" Mr. Huffham put this question in a tone of voice which would have been eminently useful had he been addressing some person a couple of miles away, but which in his present situation almost made the panes of glass rattle in the windows. "Who was it, then?" And he caught hold of Ellis and shook him with such velocity to and fro that it was difficult for a moment to distinguish what it was that he was shaking.

"It--was--Whe-e-eler!" gasped Ellis, struggling with his breath.

"Now, just you listen to me, you boys!" began Mr. Huffham. (They could scarcely avoid listening to him, considering that he spoke in what was many degrees above a whisper.) "I'll put it this way, so that we can have things fair and square, and know what we're a-doing of. There's a pound's damage been done here, so perhaps one of you gentlemen will let me have a sovereign. I'm not going to ask who did it; I'm not going to ask no questions at all: all I says is, perhaps one of you young gentlemen will let me have a sovereign." He stretched out his hand as though he expected to receive a sovereign then and there; as it happened he stretched it out in the direction of Bertie Bailey.

Bertie looked at the horny, dirt-grimed palm, then up in Mr. Huffham's face. A dog-fancier would have said that there was some scarcely definable resemblance to the bull-dog in the expression of his eyes. "You won't get a sovereign out of me," he said.

"Oh, won't I? we'll see!"

"We will see. I'd nothing to do with it; I don't know who did do it. You shouldn't leave the place without a light; who's to see in the dark?"

"You let me finish what I've got to say, then you say your say out afterwards. What I say is this--there's a pound's worth of damage done----"

"There isn't a pound's worth of damage done," said Bertie.

Mr. Huffham caught him by the shoulder. "You let me finish out my say! I say there is a pound's worth of damage done; you can settle who it was among you afterwards; and what I say is this, either you pays me that pound before you leave this shop or I'll give the whole four of you such a flogging as you never had in all your days--I'll skin you alive!"

"It won't give me my money your flogging them," wailed Mrs. Huffham from behind the counter. "It's my money I wants! Here is all them bottles broken, and the case smashed--and it cost me two pound ten, and everything inside of it's a-ruined. It's my money I wants!"

"It's what I wants too; so which of you young gents is going to hand over that there sovereign?"

"Wheeler's got sevenpence," suggested Griffin.

"Sevenpence! what's sevenpence? It's a pound I want! Which of you is going to fork up that there pound?"

"There isn't a pound's worth of damage done," said Bertie; "nothing like. If you let us go, we'll get five shillings somehow, and bring it you in a week."

"In a week--five shillings! you catch me at it! Why, if I was once to let you outside that door, you'd put your fingers to your noses, and you'd call out, 'There goes old Huffham! yah--h--h!'" And he gave a very fair imitation of the greeting which the sight of him was apt to call forth from the very youths in front of him.

"If they was the young gentlemen they calls themselves they'd pay up, and not try to rob an old woman what's over seventy year."

"Now then, what's it going to be, your money or your life? That's the way to put it, because I'll only just let you off with your life, I'll tell you. Look sharp; I want my tea! What's it going to be, your money, or rather, my old grandmother's money over there, an old woman who finds it a pretty tight fit to keep herself out of the workhouse----"

"Yes, that she do," interpolated the grandmother in question.

"Or your life?" He looked in turn from one boy to the other, and finally his gaze rested on Bailey.

Bertie met his eyes with a sullen stare. "I tell you I'd nothing to do with it," he said.

"And I tell you I don't care that who had to do with it," and Mr. Huffham snapped his fingers. "You're that there pack of liars I wouldn't believe you on your oath before a judge and jury, not that I wouldn't!" and his fingers were snapped again. He and Bailey stood for a moment looking into each other's face.

"If you hit me for what I didn't do, I'll do something worth hitting for."

"Will you?" Mr. Huffham caught him by the shoulder, and held him as in a vice.

"Don't you hit me!"

Apparently Mrs. Huffham was impressed by something in his manner. "Don't you hit 'un hard! now don't you!"

"Won't I? I'll hit him so hard, I'll about do for him, that's about as hard as I'll hit him." A look came into Mr. Huffham's face which was not nice to see. Bailey never flinched; his hard-set jaw and sullen eyes made the resemblance to the bulldog more vivid still. "You pay me that pound!"

"I wouldn't if I had it!"

In an instant Mr. Huffham had swung him round, and was raining blows with his clenched fist upon the boy's back and shoulders. But he had reckoned without his host, if he had supposed the punishment would be taken quietly. The boy fought like a cat, and struggled and kicked with such unlooked-for vigour that Mr. Huffham, driven against the counter and not seeing what he was doing, struck out wildly, knocked the lamp off its nail with his fist, and in an instant the boy and the man were struggling in the darkness on the floor.

Just then a stentorian voice shouted through the glass window of the rickety door,--

"Bravo! that's the best plucked boy I've seen!"

Chapter IV

A LITTLE DRIVE

Those within the shop had been too much interested in their own proceedings to be conscious of a dog-cart, which came tearing through the darkening shadows at such a pace that startled pedestrians might be excused for thinking that it was a case of a horse running away with its driver. But such would have been convinced of their error when, in passing Mrs. Huffham's, on hearing Mr. Stephen bellowing with what seemed to be the full force of a pair of powerful lungs, the vehicle was brought to a standstill as suddenly as a regiment of soldiers halt at the word of command. The driver spoke to the horse,--

"Steady! stand still, old girl!" The speaker alighted. Approaching Mrs. Huffham's, he stood at the glass-windowed door, observing the proceedings within; and when Mr. Stephen, in his blind rage, struck the lamp from its place and plunged the scene in darkness, the unnoticed looker-on turned the handle of the door and entered the shop, shouting, in tones which made themselves audible above the din,--

"Bravo! that's the best plucked boy I've seen!" And standing on the threshold, he repeated his assertion, "Bravo! that's the best plucked boy I've seen." He drew a box of matches from his pocket, and striking one, he held the flickering flame above his head, so that some little light was shed upon what was going on within. "What's this little argument?" he asked.

Seeing that Mr. Huffman was still holding Bailey firmly in his grasp, "Hold hard, big one," he said; "let the little chap get up. You ought to have your little arguments outside; this place isn't above half large enough to swing a cat in. Granny, bring a light!"

As the match was just on the point of going out he struck another, and entered the shop with it flaming in his hand. Mrs. Huffham's nerves were too shaken to allow her to pay that instant attention to the new-comer's orders which he seemed to demand.

"Look alive, old lady; bring a light! This old band-box is as dark as pitch."

Thus urged, the old lady disappeared, presently reappearing with a little table-lamp in her trembling hands.

"Put it somewhere out of reach--if anything is out of reach in this dog-hole of a place. I shouldn't be surprised if you had a little bonfire with the next lamp that's upset."

Mrs. Huffman placed it on a shelf in the extreme corner of the shop, from which post of vantage it did not light the scene quite so brilliantly as it might have done. Mr. Stephen and the boy, relaxing a moment from the extreme vigour of discussion, availed themselves of the opportunity to see what sort of person the stranger might chance to be.

He was a man of gigantic stature, probably considerably over six feet high, but so broad in proportion that he seemed shorter than he actually was. A long waterproof, from which the rain was trickling in little streams, reached to his feet; the hood was drawn over his head, and under its shadow was seen a face which was excellently adapted to the enormous frame. A huge black beard streamed over the stranger's breast, and a pair of large black eyes looked out from overhanging brows. He was the first to break the silence.

"Well, what is this little argument?" Then, without waiting for an answer, he continued, addressing Mr. Huffham, "You're rather a large size, don't you think, for that sized boy?"

"Who are you? and what do you want? If there's anything you want to buy, perhaps you'll buy it, and take yourself outside."

The stranger put his hand up to his beard, and began pulling it.

"There's nothing I want to buy, not just now." He looked at Bailey. "What's he laying it on for?"

"Nothing."

"That's not bad, considering. What were you laying it on for?" This to Huffham.

"I've not finished yet, not by no manner of means; I mean to take it out of all the lot of 'em. Call themselves gents! Why, if a working-man's son was to behave as they does, he'd get five years at a reformatory. I've known it done before today."

"I daresay you have; you look like a man who knew a thing or two. What were you laying it on for?"

"What for? why, look here!" And Mr. Huffham pointed to the broken bottles and the damaged case.

"And I'm a hard-working woman, I am, sir, and I'm seventy-three this next July; and it's hard work I find it to pay my rent: and wherever I'm to get the money for them there things, goodness knows, I don't. It'll be the workhouse, after all!" Thus Mrs. Huffham lifted up her voice and wept.

"And they calls themselves gents, and they comes in here, and takes advantage of an old woman, and robs her right and left, and thinks they're going to get off scot free; not if I know it this time they won't." Mr. Stephen Huffham looked as though he meant it, every word.

"Did you do that?" asked the stranger of Bailey.

"No, I didn't."

"I don't care who did it; they're that there liars I wouldn't believe a word of theirs on oath; they did it between them, and that's quite enough for me."

"I suppose one of you did do it?" asked the stranger.

Bailey thrust his hands in his pockets, looking up at the stranger with the dogged look in his eyes.

"The place was pitch dark; why didn't they have a light in the place?"

"Because there didn't happen to be a light in the place, is that any reason why you should go smashing everything you could lay your hands on? Why couldn't you wait for a light? Go on with you! I'll take the skin off your back!"

"How much?" asked the stranger, paying no attention to Mr. Stephen's eloquence.

"There's a heap of mischief done, heap of mischief!" wailed the old lady in the rear.

"How am I to tell all the mischief that's been done? Just look at the place; a sovereign wouldn't cover it, no, that it wouldn't."

"There isn't five shillings' worth of harm," said Bertie. "If you were to get five shillings, you'd make a profit of half a crown."

The stranger laughed, and Mr. Huffham scowled; the look which he cast at Bertie was not exactly a look of love, but the boy met it without any sign of flinching.

"I'll be even with you yet, my lad!" Mr. Stephen said.

"If I give you a sovereign you will be even," suggested the stranger.

Mr. Stephen's eyes glistened; and his grandmother, clasping her old withered palms together, cast a look of rapture towards the ceiling.

"Oh, deary me! deary me!" she said.

"It's a swindle," muttered Bertie.

"Oh, it's a swindle, is it?" snarled Mr. Stephen. "I'd like to swindle you, my fighting cock."

"You couldn't do it," retorted Bertie.

The stranger laughed again. Unbuttoning his waterproof, and in doing so distributing a shower of water in his immediate neighbourhood, out of his trousers pocket he took a heavy purse, out of the purse he took a sovereign, and the sovereign he handed to Mr. Stephen Huffham. Mr. Stephen's palm closed on the glittering coin with a certain degree of hesitation.

"Now you're quits," said the stranger, "you and the boy."

"Quits!" said Bertie, "it's seventeen-and-sixpence in his pocket!"

Mr. Stephen smiled, not quite pleasantly; he might have been moved to speech had not the stranger interrupted him.

"You're pretty large, and that's all you are; if this boy were about your size, he'd lay it on to you. I should say you were a considerable fine sample of a--coward."

Mr. Stephen held his peace. There was something in the stranger's manner and appearance which induced him to think that perhaps he had better be content with what he had received. After having paused for a second or two, seemingly for some sort of reply from Mr. Huffham, the stranger addressed the boys.

"Get out!" They went out, rather with the air of beaten curs. The stranger followed them. "Get up into the cart; I'm going to take you home to my house to tea." They looked at each other, in doubt as to whether he was jesting. "Do you hear? Get up into the cart! You, boy," touching Bailey on the shoulder, "you ride alongside me."

Still they hesitated. It occurred to them that they had already broken their engagement with the credulous Mr. Shane, broken it in the most satisfactory manner, in each separate particular. They were not only wet and muddy, looking somewhat as though they had recently been picked out of the gutter, but that half-hour within which they had pledged themselves to return had long since gone. But if they hesitated, there was no trace of hesitation about the stranger.

"Now then, do you think I want to wait here all night? Tumble up, you boy." And fairly lifting Wheeler off his legs, he bore him bodily through the air, and planted him at the back of the trap. And not Wheeler only, but Griffin and Ellis too. Before those young gentlemen had quite realized their position, or the proposal he had made to them, they found themselves clinging to each other to prevent themselves tumbling out of the back of what was not a very large dog-cart. "You're none of you big ones! Catch hold of each other's hair or something, and don't fall out; I can't stop to pick up boys. Now then, bantam, up you go."

And Bertie, handled in the same undignified fashion, found himself on the front seat beside the driver. The stranger, big though he was, apparently allowed his size to interfere in no degree with his agility. In a twinkling he was seated in his place by Bertie.

"Steady!" he cried. "Look out, you boys!" He caught the reins in his hands; the mare knew her master's touch, and in an instant, even before the boys had altogether yet quite realized their situation, they were dashing through the darkening night.

It was about as cheerless an evening as one could very well select for a drive in an open vehicle. The stranger, enveloped in his waterproof, his hood in some degree sheltering his face, a waterproof rug drawn high above his knees, was more comfortable than the boys. Bailey, indeed, had a seat to sit upon and a share of the rug, but his friends had neither seat nor shelter.

Perhaps, on the whole, they would have been better off had they been walking. The imperfect light and the hasty start rendered it difficult for them to have a clear view of their position. The mare--which, had it been lighter and they versed in horseflesh, they would have been able to recognise as a very tolerable specimen of an American trotter--made the pace so hot that they had to cling, if not to each other's hair, at least to whatever portion of each other's person they could manage to get hold of. Even then it was only by means of a series of gymnastic feats that they were able to keep their footing and save themselves from being pitched out on to the road.

They had not gone far when Griffin had a disaster.

"I've lost my hat!" he cried. Wind and pace and nervousness combined had loosened his headgear, and without staying to bid farewell to his head, it disappeared into the night.

The stranger gave utterance to a loud yet musical laugh.

"Never mind your hat! Can't stop for hats! The fresh air will do you good, cool your head, my boy!" But this was a point of view which did not occur to Griffin; he was rather disposed to wonder what Mr. Shane and Mrs. Fletcher would say.

"I wish you wouldn't catch hold of my throat; you'll strangle me," said Wheeler, as the vehicle dashed round a sharp turn in the road, and the hatless Griffin made a frantic clutch at his friend to save himself from following his hat.

"I--can't--help--it," gasped his friend in reply. "I wish he wouldn't go so fast. Oh--h!"

The stranger laughed again.

"Don't tumble out! we can't stop to pick up boys! Hullo! what are you up to there?"

The trio in the rear were apparently engaged in a fight for life. They were uttering choking ejaculations, and struggling with each other in their desperate efforts to preserve their perpendicular. In the course of their struggle they lurched against the stranger with such unexpected violence that had he not with marvellous rapidity twisted round in his seat and caught them with his arm, they would in all probability have continued their journey on the road. At the same instant, with his disengaged hand he brought the horse, who seemed to obey the directions of its master's hand with mechanical accuracy, to a sudden halt.

"Now, then, are you all right?"

They were very far from being all right, but were not at that moment possessed of breath to tell him so. Had they not lost the power of speech they would have joined in a unanimous appeal to him to set them down, and let them go anywhere, and do anything, rather than allow them to continue any longer at the mercy of his too rapid steed. But the stranger seemed to take their involuntary silence for acquiescence. Once more they were dashing through the night, and again they were hanging on for their bare lives.

"Like driving, youngster?" The question was addressed to Bailey. "Like horses? Like a beast that can go? Mary Anne can give a lead to a flash of lightning and catch it in two T's."

"Mary Anne" was apparently the steed. At that moment the trio in the rear would have believed anything of Mary Anne's powers of speed, but Bailey held his peace. The stranger went on.

"I like a drive on a night like this. I like dashing through the wind and the darkness and the rain. I like a thing to fire my blood, and that's the reason why I like you. That's the reason why I've asked you home to tea. What's your name?"

"Bailey, sir."

"I knew a man named Bailey down in Kentucky who was hanged because he was too fond of horses--other people's, not his own. Any relation of yours?" Bertie disclaimed the soft impeachment.

"I don't think so, sir."

"There's no knowing. Lots of people are hanged without their own mothers knowing anything about it, let alone their fathers, especially out Kentucky way. A cousin of mine was hanged in Golden City, and I shouldn't have known anything about it to this day if I hadn't come along and seen his body swinging on a tree. As nice a fellow as man need know, six-feet-one-and-three-quarters in his stockings--three-quarters of an inch shorter than me. They explained to me that they'd hanged him by mistake, which was some consolation to me, anyway, though what he thought of it is more than I can say. I cut him down, dug a hole seven foot deep, and laid him there to sleep; and there he sleeps as sound as though he'd handed in his checks upon a feather bed."

Bailey looked up at the speaker. He was not quite sure if he was in earnest, and was anything but sure that the little narrative which he rolled so glibly off his tongue might not be the instant coinage of his brain. But something in the speaker's voice and manner attracted him even more than his words; something he would have found it difficult to describe.

"Is that true?" he asked.

The stranger looked down at him and laughed.

"Perhaps it is, and perhaps it isn't." He laughed again. "Wet, youngster?"

"I should rather think I am," was Bertie's grim response. All the stranger did was to laugh again. Bailey ventured on an inquiry. "Do you live far from here?" He was conscious of a certain degree of interest as to whether the stranger was driving them to Kentucky; he, too, had Mr. Shane and Mrs. Fletcher in his mind's eye. "Shane'll get sacked for this, as sure as fate," was his mental observation. He was aware that at Mecklemburg House the sins of the pupils not seldom fell upon the heads of the assistant-masters.

"Pain's Hill," was the answer to his question. "Ever heard of Washington Villa?" Bertie could not say he had.

"I am George Washington Bankes, the proprietor thereof. Yes, and it isn't so long ago that if any one had said to me that I should settle down as a country gentleman, I should have said, 'There have been liars since Ananias, but none quite as big as you.'"

Bailey eyed him from a corner of his eye. His father was a medical man, with no inconsiderable country practice. He had seen something of country gentlemen, but it occurred to him that a country gentleman in any way resembling his new acquaintance he had not yet chanced to see.

"You at the school there?"

Taking it for granted that he referred to Mecklemburg House, Bertie confessed that he was.

"Why don't you run away? I would."

Bertie started; he had read of boys running away from school in stories of the penny dreadful type, but he had not yet heard of country gentlemen suggesting that course of action as a reasonable one for the rising generation to pursue.

"Every boy worth his salt ought to run away. I did, and I've never done a more sensible thing to this day." In that case one could not but wonder for how many sensible things Mr. George Washington Bankes had been remarkable in the course of his career. "I've been from China to Peru, from the North Pole to the South. I've been round the world all sorts of ways; and the chances are that if I hadn't run away from school I should never have travelled twenty miles from my old mother's door. Why don't you run away?"

Bertie wriggled in his seat and gasped.

"I--I don't know," he said.

"Ah, I'll talk to you about that when I get you home. You're about the best plucked lad I've seen, or you wouldn't have stood up in the way you did to that great hulking lubber there; and rather than see a lad of parts wasting his time at school--but you wait a bit. I'll open your eyes, my lad. I'll give you some idea of what a man's life ought to be! Books never did me any good, and never will. I say, throw books, like physic, to the dogs--a life of adventure's the life for me!"

Bertie listened open-eyed and open-mouthed; he began to think he was in a waking dream. There was a wildness about his new acquaintance, and about his mode of speech, which filled him with a sort of dull, startled wonder. There was in the boy, deep-rooted somewhere, that half-unconscious longing for things adventurous which the British youngster always has. Mr. Bankes struck a chord which filled the boy almost with a sense of pain.

"A life of adventure's the life for me!" Mr. Bankes repeated his confession of faith, laughing as he did so; and the words, and the voice, and the manner, and the laugh, all mixed together, made the boy, wet as he was, glow with a sudden warmth. "A life of adventure's the life for me!"

The drive was nearly ended, and during the rest of it Mr. Bankes kept silence. Wheeler's hat had followed Griffin's, but he had not mentioned it; partly because, as he thought, he would receive no sympathy and not much attention, and partly because, in his anxiety to keep his footing in the trap, and get out of it with his bones whole, it would have been a matter of comparative indifference to him if the rest of his clothing had followed his hat. But he, too, mistily wondered what Mr. Shane and Mrs. Fletcher would say.

Fortunately for his peace of mind, and the peace of mind of his two friends, the good steed, Mary Anne, brought them safely to the doors of Washington Villa. Fond of driving as they were, as a rule, they were conscious of a distinct sense of relief when that drive was at an end.

Chapter V

AN EVENING AT WASHINGTON VILLA

Washington Villa appeared, from what one could see in the darkness, to be a fairly sized house, standing in its own grounds. Considerable stabling was built apart from, but close to the house, and as the trap dashed along the little carriage-drive numerous loud-voiced dogs announced the fact of an arrival to whomever it might concern. The instant the vehicle stopped, the hall door was opened, and a little wizened, shrunken man came down the steps. Mr. Bankes threw him the reins.

"Jump out, you boys, and tumble into the house. Welcome to Washington Villa." Suiting the action to the word, and before his young friends had clearly realized the fact of their having arrived at their destination, he had risen from his seat, sprung to the ground, and was standing on the threshold of the door. The boys were not long in following suit.

"Come this way!" Striding on in front of them, through a hall of no inconsiderable dimensions, he led them into a room in which a bright fire was blazing, and which was warm with light. A pretty servant girl made a simultaneous entrance through a door on the other side of the room. "Catch hold." Tearing rather than taking off his waterproof and hood, he flung them to the maid. "Where are my slippers?" The maid produced a pair from the fender, where they had been placed to warm; and Mr. Bankes thrust his feet into them, flinging his boots off on to the floor. "Tea for five, and a good tea, too, and in about less time than it would take me to shoot a snake."