Swiss Fairy Tales

William Elliot Griffis

FOLK-LORE BOOKS

By WILLIAM E. GRIFFIS

Swiss Fairy Tales

An entirely new sheaf of stories

Dutch Fairy Tales

A mine of legend and child-lore

Belgian Fairy Tales

Showing manners and customs of the people themselves

Fire Fly’s Lovers

Japanese fairy tales

The Unmannerly Tiger

Korean fairy tales

Welsh Fairy Tales

(In preparation)

Each book illustrated in color

THOMAS Y. CROWELL CO., NEW YORK

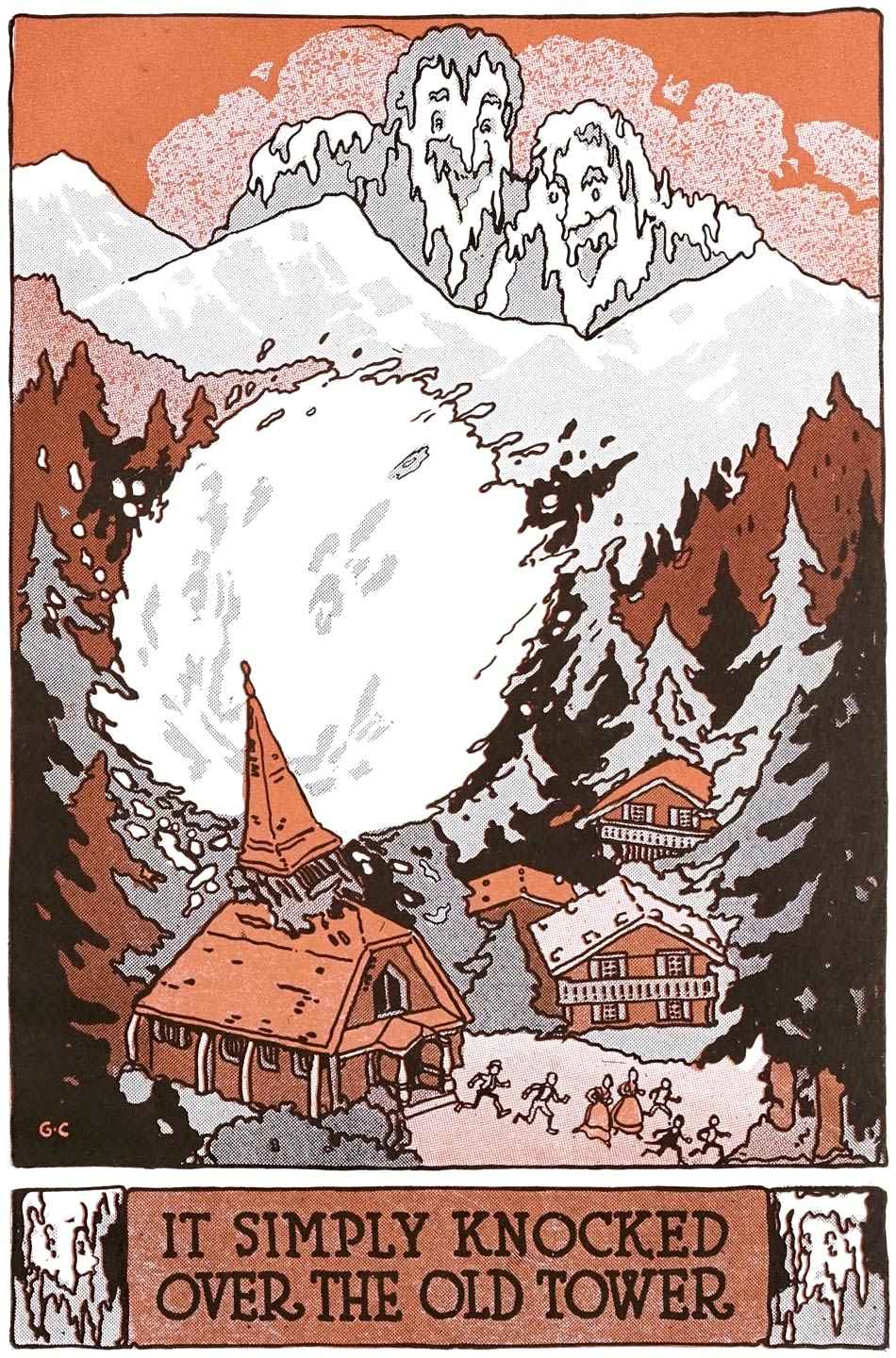

IT SIMPLY KNOCKED OVER THE OLD TOWER

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1920,

By Thomas Y. Crowell Co.

DEDICATED

IN RADIANT MEMORIES

OF MY SWISS MATERNAL ANCESTRY

NEAR VALLEY FORGE

FROM WHOSE LIPS I FIRST HEARD STORIES OF

WASHINGTON, LAFAYETTE, STEUBEN

AND OF SWITZERLAND

THE LAND OF THE EDELWEISS [v]

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | How Swiss Fairy Tales Came to America | 1 |

| II. | The Swiss Home Near Valley Forge | 16 |

| III. | The Wonderful Alpine Horn | 28 |

| IV. | The Whimsical Avalanche | 39 |

| V. | The Mountain Giants | 48 |

| VI. | The Dwarf and His Confectionery | 56 |

| VII. | Two Good Natured Dragons | 66 |

| VIII. | The Frost Giants and the Sunbeam Fairies | 77 |

| IX. | The Fairy in the Cuckoo Clock | 91 |

| X. | The Castle of the Hawk | 101 |

| XI. | The Yodel Carillon of the Cows | 110 |

| XII. | The Tailor and the Giant | 118 |

| XIII. | The Dwarf’s Secret | 132 |

| XIV. | The Fairy of the Edelweiss | 144 |

| XV. | The Avalanche That Was Peace Maker | 157 |

| XVI. | The Fairies and Their Playground | 168 |

| XVII. | The Kangaroo Poa | 181 |

| XVIII. | The Swiss Fairies in Town Meeting | 191 |

| XIX. | The Palace Under the Waves | 201 |

| XX. | The Alpine Hunter and His Fairy Guardian | 209 |

| XXI. | The Fairies’ Palace Car | 221 |

| XXII. | The White Chamois | 235 |

| XXIII. | The Siren of the Rhine | 241 |

| XXIV. | The Ass That Saw the Angel | 250 |

[1]

Swiss Fairy Tales

I

HOW SWISS FAIRY TALES CAME TO AMERICA

Let us pretend that we are sitting on a stool, a hassock, a rug, or the floor, around the chair of grandmother Hess, to which place all young folks are hereby invited. We shall go with her, in fancy, to the home of the Swiss family Harby, for that was her maiden name, at Barren Hill, in what the Swiss folks called “the Pennsylvanias.” For they loved the forests and they knew that the name meant the groves or woods of Penn. They kept always, in their minds, the idea of trees. It was there that some of these fairy and other tales were first told.

It was long ago, during the Revolutionary war, when Washington, and Lafayette, and Steuben, were comrades at Valley Forge. This [2]place was only a few miles away, and the great men rode often past the house and farm of John Harby, who was grandma’s father.

When, in 1778, the Hessians and red coats could not capture Lafayette, with his Continental soldiers, they stole the bread out of the oven and drank up the milk from the spring house.

The little girls, Sarah, Hannah and Margaret, often heard from their grandfather and grandmother about Switzerland, whence, following William Penn, they had come. Their kinsfolk still lived in the old land across the sea. When the Revolutionary war was over, their father, John Harby, came to the Quaker City, and kept a hotel. There, when Philadelphia was the national capital, he entertained members of Congress and the refugee French noblemen.

When the story teller heard the once little maids talk about things Swiss, and Hessian, and British, and Pennsylvanian, these three, two of whom the Hessians had once scared into the garret, were dear old ladies. Sitting up in bed, or in her chair, as straight as her rheumatism and her bent fingers would allow, grandmother told us many a tale of Swiss ancestral and Revolutionary times.

To the end of the years of her life, which lasted from 1770 to 1866, her sister Hannah, our maiden aunt, sang the songs, played on the piano [3]the ditties, and danced the minuets and waltzes, which the French officers and noblemen had taught her when the Quaker city, from 1790 to 1800, was the national capital.

We children, even when big girls and boys, and ready for college, enjoyed the fun, the music, and the stories. It was from these dear old ladies that the story teller learned to love the mountains, and to climb them, in America and Japan, and, for weeks at a time, to tramp among them in glorious Switzerland.

The ancestral Swiss home was in a valley of the Bernese Oberland, under the shadow of a high mountain. In winter, which usually lasted seven months or more, the people, the boys, and the girls, the cows, goats, donkeys, horses, chickens, and all living things were shut in by heavy snows. Quite often in winter, daddy and the boys had to climb out the windows onto the snows that were piled, or drifted, many feet high against the door. Even on May day, spoiling fun outdoors, there might come a storm which left six or eight feet of snow.

Yet when the sun got up early in the morning, and the south wind blew with a quiet force that did more in a day’s work than a million steam shovels, the snow melted, and soon the green meadows were spangled with red and blue, yellow and white flowers. [4]

When June came, the big boys got ready, with their fathers and hired men, to leave their village home, and go up to spend the whole summer on the spicy pastures, that is, the Alps, high up on the mountains, to stay until near October. There the bees would gather honey from the nectar in the blossoms, and cows would feed on the sweet juices of the grass. It was at this season that the milk, cream, butter and cheese, were the very best of the year. Many a growing boy, counting on his fingers the days, looked forward for months to life outdoors, on the highlands, among the birds, the butterflies and the wild animals. As for the cattle, they could sniff the sweet aroma of the flowery fields and grasses at a distance and long before men could.

The day of the great cow parade, when the other four-footed animals, dogs, goats, pigs, horses and donkeys, joining in, was the greatest of the year. Then the leading cow, named Lady, or Queenie, or Cleopatra, often carrying the milking stool on her head, between her horns, led the procession. The girls were all out in their best clothes to deck the hats of the daddies with wreaths and blossoms, and to say and wave good-byes. Pretty nearly every one was decorated with flowers.

Then the music and the yodel songs, and the blowing of the pine wood horns began. These [5]awoke the echoes of the distant mountains. Then the sounds, returning, seemed as sweet as the singing by a choir of the heavenly host. No Swiss boy or girl, even when grown up, living in the cities, or in a foreign land, ever forgot the yodel songs, or the hymns his mother used to sing.

The Swiss chateau, home of the Harbys, before the year 1710, except the first story, which was of stone, was entirely of wood. In winter, the fireplace of brick roared with logs of fir, birch or oak. The great white porcelain stove, eight feet high, banded with shining brass, in which peat, or coal, was the fuel, stood at one end of the main room.

To get into the house, the door, in the front centre, opened into the basement, but there were two stairways on the outside, which took one up into the bedrooms. To let the heavy snow slide off easily, to the ground, the eaves projected from the roof six feet beyond and over the walls. Within the projecting front gable, between the sloping roof and the second story, there was a balcony.

The whole front of the house was nearly hidden by vines and flowers that invited the bees and birds, though there were hives and dovecotes in the yard space, fronting the house. Cut into the corner columns, or through the gable [6]boards, was this Scripture sentence: “As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.”

Not far away was the barn and yard for the cows and chickens, ducks and geese. Near by, the purling of a running brook, fed from the mountain with water, cold, and clear as crystal, was like the singing of a sweet song. As neat as a new pin was this Spring House. Here upon shelves, only a little higher than the stream, and on the stone surbase that ran across one side of the low room, or floating in the cold water, were shallow pans for the milk. In a corner stood the big jar, to hold the cream, which was daily skimmed from the milk in the pans. The caldron and utensils for cheesemaking were kept in another corner. It was from cheese chiefly that the family lived, especially in winter.

On the walls of the sleeping chambers, parlor, and living room, besides the well-mounted antlers of the wild mountain goat, and the chamois, there were framed pictures of the great men of the Fatherland. Here looked down the face of the holy saint Fridolin, or the reformer Zwinglius, or the heroes, William Tell and Arnold von Winkelried. In some houses, one could see a picture of Calvin, or a view of Geneva, or the seal of the canton in which they lived. In a glass-covered case were dried Alpine flowers, rock roses, violets and anemones, with their colors [7]kept wonderfully fresh, even in winter. When first plucked, they were put in hot sand—not too hot—and covered for a time.

For breakfast, the Harbys had honey, bread, milk and eggs. On the wall, resting on pegs, was the father’s gun, for hunting. It was a real rifle, and few men in the world, except the Swiss and the Jäger, or hunters, then knew of this wonderful weapon.

For dinner, they often had chamois or ibex, and, occasionally, bear meat, for John Harby was a dead shot with the rifle. Beef, with greens, was common, though the chief staple of food was cheese, or cream cooked in many wonderful ways, with cheese-cake, or pie, though buttermilk was in daily demand.

What the young folks liked, best of all, was the weekly treat of “schnitzel.” This was made of boiled ham, dumplings of wheat flour, dried apples and spices, and was served on the table with molasses. When nicely cooked, and, as mother knew how to make it, nothing tasted better. It was enjoyed until the waist belts of youngsters began to tighten.

Every morning, the doors of the clock, set in a box or house on the wall, flew open, and the cuckoo chirped its song and then retired inside from view. The wooden bird thus gave notice [8]that it was time to get up and make ready for school.

At night, before the children went to sleep, Mother, and sometimes Daddy, told them fairy or wonder tales, or of the heroes that had made Switzerland free, or the Bible stories, till they knew these by heart, and, when they grew up, told them to their children.

With the young men of the village, it was not always work—in winter with the cows and goats, in the dairy at home; or, in summer the driving of the flock up to the mountain pastures, with the cheesemaking there. Tired of the monotony of country life, the sturdy lads welcomed the advent of the soldiers, in bright, gay uniforms, with a band of music, and the recruiting officer at their head.

With their flags and banners, these strangers came from the great world outside, to enlist young men for military service, in France or Germany, or for the Scotch Brigade in the Netherlands, or, to serve the King of England, in America. All the village folk turned out and the mothers and maidens were as eager as the fathers, to see how it was done, before their sons, brothers and sweethearts marched away. Not least among these Swiss, who gained fame, was General Henry Bouquet, who, in the British [9]service, and as comrade of Washington, won Pittsburg for the King.

For these were the gala days of monarchs and of the soldier of fortune, that is, of the brave young man, who left his home and country to fight for any one who paid him well. He enlisted, more for love of adventure, than for love of the ruler whose splendid uniform he wore. Yet his loyalty and honor were steadfast. Faithful and brave, he lived in camps and barracks, fought battles, and died in the hospital, or on the field.

When the king’s officer raised his banner aloft, in the public square of the Swiss village, the fifer and drummer, or trumpeter, sounded the call. On one side of the broad table, well furnished, and with a foaming pitcher and cups to drink the king’s health, sat the notary. Then up came the stalwart young fellows, in their working clothes, to have their names enrolled, to take the oath of allegiance, and to exchange their pitchforks for muskets, bayonets and cartridge boxes. Then they took their places with the others, and soon wore gay soldier clothes, with shining buttons, and frontlets of brass on their helmets.

Often it was hard, not only for parents and sisters, but for the pet dogs, to leave the dear masters. Many were the tears shed, and lively the gossip among the women at and around the [10]well curb, when the village had again resumed its quiet life.

Greater yet was the glory, when the lad, who had left in peasant homespun, returned, in the royal uniform, to tell of camps, and battles, and sieges; yes, even of palaces and the splendor of the great cities, far away. Buttons were a new fashion, then, and the Swiss soldier came back home, in cocked hat, a coat very much dotted with shining brass, and opened to show the vest and facings, and with leggings reaching from ankle to knee. A high private, in those days, looked as gay as a tropical bird, and as handsome as a prince.

The boys left their hoops, and the girls their dolls, to run and welcome the returning hero. Old and young listened to his war stories, and even the dogs and pigeons seemed to share in the joy. The imagination of the youngsters was fired, and often maidens followed their lovers to distant countries. Who has not read, in the pages of Froissart, or Macaulay, of “Appenzell’s stout infantry,” or of the valor and devotion of the Swiss Guard, in the Tuilleries at Paris, who “died to defend their master.” In their everlasting honor, one sees at Luzerne, sculptured out of the solid rock, the dying lion. This splendid work of art symbolizes the loyalty [11]and valor of the seven hundred and eighty-six victims, of the French mob, in 1793.

While the young men had opportunity to see the great world, beyond the mountains, most of the girls stayed at home in the valleys. Yet all the time, they thought of their brothers, lovers and kinsmen. They, too, longed to see a real prince, and to look on a military pageant, and gaze on the splendor of courts and palaces. At times, it was hard to restrain the maidens from roaming off, down the Rhine, to the rich and gay city of Amsterdam, or to the brilliancy of Paris.

It was not alone in Europe that the absentees from the Swiss villages started. Already, late in the eighteenth century, men of the Grisons and Oberland were hearing of the “Pennsylvanias.” The William Penn country was luring the stalwarts away, for reports came across seas, as sweet in sound as yodel songs, or as Alpine echoes, of fertile soil, which was dirt cheap. The kind ruler, of the Forests of Penn, hated war and treated even the wild men, or Indians, kindly. He bought their land and paid them for it, even though his King, Charles, called it his own—which his friend Roger Williams denied.

Sometimes a Swiss mother, left a widow, because her husband had been killed in some prince’s battle, resolved not to let her boy die [12]for a king. So she strapped her baby on her back, and skated down the Rhine to Rotterdam, and reached America. One of these, well known, married again, and in Philadelphia reared a fine family of splendid boys and girls. Such a romantic incident happened more than once.

Hardly had the Harbys begun even to talk about Penn’s land, when a terrible calamity befell them, which drove them out of their nest-like home, even as the mother-eagle pushes out her fledgelings, while the wonderful opportunity offered them, in Penn’s Groves, lured them to even greater ease and comforts. Across the Atlantic, there would be less of toil, than in their mountain home, with its long months of winter and its short weeks of summer.

The story would take too much time to tell, if we tried to note every detail. For a week previous, the snow had fallen continuously. It darkened the air, and covered the earth with many feet of solid whiteness. One old man was full of forebodings of calamity. On the edge of a cliff, far up on the mountain side, mighty masses of snow piled up, stood like a lofty tower, in terrible menace, likely soon to fall. All were hoping for the Föhn, or south wind, to blow and “eat up” the snow.

Unsuspecting a storm, a hunter had, some days before, gone among the heights, taking his [13]provisions and blanket, hoping to stalk an ibex, or at least a chamois. Caught in the sudden, blinding, whirling snow, and unable to find the path homeward, he built a rude shelter at the edge of the forest. This was opposite an overhanging rock, under this snow tower, which was steadily rising in height. Having enough rations in his wallet to last him four days, he waited till sunshine should come, hoping to see a troop of chamois, making their way down over the narrow ledge of rock, in search of moss for food. Fortunately for him, but calamitously for the village, his rifle shot brought down a fat buck.

Yet immediately upon that shock of the air, following the gunfire and report, fell tons upon tons of snow and ice. The mass, rolling down with lightning speed, increased in size at every yard. It fell on the village, overwhelming houses, barns, stables and gardens. Where yesterday were happy homes were now many human victims. Today, the mouldering stones in the church yard witness to the awful catastrophe. Pathetic is a similar record, made ten years later, in another village. “Dear God! What sorrow! Eighty-eight in a single tomb.”

Happily the Harby home, being on the edge of the avalanche’s track, though flattened out, like a sheet of mussed-up paper, had no human dead within its walls; though in the barn every [14]living animal was smothered by the weight of white.

Digging out a few necessary things, including the trusty rifle, unharmed, they packed them up, because they would be very necessary in the new home, or because they were linked with affectionate memories. They were happy in finding the stocking full of coin, which had been hidden behind a loose stone in the fireplace. Then the family made its way to Basle, on the Rhine. There they took boat, down the river to Rotterdam; where, with hundreds of other Swiss folks, they were sheltered, helped and kindly treated by the Dutch ministers and people.

Getting on board the ship “Arms of Rotterdam,” under the tricolor flag, red, white and blue of the Republic, they crossed the Atlantic and in Penn’s “Holy Experiment,” where thousands of Swiss folk had arrived before them, they reached safely the city of Brotherly Love. It was then little larger than a village. When the people from Wales, England, Holland and Germany first came and were building their houses, they had lived in caves, on the banks of the Delaware river, where now is Front Street; but when Harbys arrived there were hundreds of completed houses, some in brick, or stone, but mostly in wood. Yet even from the beginning, the land was properly surveyed, and laid out in squares, [15]and, with four large parks, and planted with trees, while some of the streets were paved. In truth, for order, and beauty, and liberal ideas, this was the queen city of America. [16]

II

THE SWISS HOME NEAR VALLEY FORGE

Only a few days did the Harbys abide on the banks of the Delaware, in the little city of Brotherly Love, where lived a few hundred people, mostly Friends, in drab clothes. Then, from one of William Penn’s land agents—the ancestor of American bishops—John Harby bought a farm. It lay on a piece of high ground, at Barren Hill, which was part of a ridge near the Schuylkill river. It was named after the bears that were still numerous in the forests that then clothed the land. It is known as Lafayette Hill and we shall soon see why. The neighborhood afforded good hunting, for any young man, that had brought his chamois rifle with him. One of the active fellows, who was reckoned a sure shot, was Harby’s nephew, of whom we shall hear later. He shot many deer and the family had venison often. Not far away was White Marsh. Over in another direction, was Fox Chase, where they had hounds and hunted foxes. [17]

Only a few miles distant, across the Hidden Stream, or Schuylkill, as the Dutch had named the river, was the valley forge, where the farmers in the region around had their tools made and mended.

Not far away, on the hill, was soon built Saint Peter’s Lutheran church. In Switzerland, the Harbys had been members of the Reformed church, but all the people of the neighborhood now worshipped together.

The Harbys made their house first of logs of wood, notched at the corners. Trees were plentiful, and the forest was near at hand. Many things were about them to remind them of their old home, though there were no glaciers, or avalanches, or high mountains, with snow lying on them all the year round, and all was as yet rough, in the new country.

When the barn had been built, the cows, pigs and fowls made things look friendly and sociable. They had no cuckoo clock any more, but it was really homelike to hear the cocks crow at sunrise. This sound was certainly much pleasanter, indeed, than to hear the howling of the wolves at night. Occasionally, early in the morning, the Harbys would see a bear in the barnyard, and they had to keep the chickens locked up in the chicken house, for foxes were plentiful, and always on the watch for a poultry dinner. Wild [18]turkeys—a new sort of bird for them—and wild pigeons were plentiful. Benjamin Franklin, who was then a little boy in Boston, the oldest in a family of seventeen children, when a grown man, wanted to make the wild turkey, which gives food to man, the national emblem, instead of the eagle, that lives on flesh and kills little birds.

Inside the house, there were wide seats at the chimney side, and puss purred in front of the great hearth fire. Outside, the dogs kept watch and ward, and often had a lively tussle with wolves and young bears.

When spring time came, the girls went blossom hunting. One very common flower, which they had known in Switzerland, the Pearly Everlasting, somehow reminded them of the Edelweiss. Daddy, who loved trees, almost to worship, saluted the same species as those which he had seen growing in the Old World—fir, birch, pine, and oak; but the persimmon tree was new to him and he enjoyed the autumn fruit, which the frost seemed to ripen; while the sugar maple was as good as a fairy tale, for the idea of a tree bearing candy was wonderful. In fact, the Harbys hailed the trees as friends, true and tried, with reverence and awe.

A generation came and went, and soon there was a little God’s acre around the little church [19]on the hill top. The Hess family, from Zurich, also had made their home near by, at Whitemarsh, and several couples of the young men and maidens of the two households made love and married together.

The fathers and mothers, who had known the old home land beyond the sea, talked often of chamois and ibex, and edelweiss and the rock roses, and the meadow flowers, and the cows and the yodel music. When they spoke of the “Alps,” they meant the summer pastures high up, and not mountains. At times, especially in June, they felt homesick for the yodel songs and the Alpine horn echoes. They spoke often of the curious things at Neuchatel, and Berne, and Zurich, and the Lake of the Four Cantons. They sang the hymns of Heimath, or Home, and of the Fatherland, and of the Heavenly Land, and recounted the exploits of the Swiss heroes. The children were taught not to be afraid of the dark, and all knew by heart many hymns, especially that beginning, “Alone, yet not alone with God am I.”

On the other hand, the new generation told of other game, deer, bear, wolf, wild turkey and pigeons, and of new fruits like the persimmon. Their model, in civil life, was the good governor, William Penn, and their hero in valor and rescue of captives was Colonel Bouquet, the Swiss soldier [20]in the service of their sovereign, Queen Anne. They loved her, also, because she loved the yodel music. Later came the kings named George. The flag over them was the Union Jack, which they saw float on the staff, when they went to Philadelphia often, and, occasionally, to Lancaster.

Yet all this time, one great desire and romantic longing of the maidens was unfulfilled. The yearning of the girls, as they became sweethearts, wives, and mothers, was handed down, as if it were a family heirloom, to see a real prince or a nobleman, or a man with a title. They hoped that some officer, in resplendent uniform, such as they had seen in their home village, would come into their neighborhood, for they were tired of Quaker drab. Even though their grandparents were democratic by their Swiss inheritance, and almost by instinct, and though reared in the oldest of republics, and accustomed to town meetings, the little maids, Sarah and Hannah, longed to see a real pageant, a prince; or at least a marquis, and something of the pomp of courts or even of armies. They heard that the Prince of Wales, who became King George II, had indeed visited New York, and skated on the ice of the Collect Pond; but he had come and gone, as a private person, and it was not likely [21]that either he, again, or even King George III would ever visit the colonies.

Before the two little girls could know what it all meant, the Harbys heard, in their home at Barren Hill, of the Continental Congress, held in Carpenters’ Hall, in Philadelphia. In this gathering Canada was represented. Then, it was hoped that there would be fourteen stripes in the flag, which the Philadelphia City Troop of cavalry were making. But when their flag was unfurled and the handsome horsemen escorted Colonel George Washington, of Virginia, to Cambridge, many felt very sorry, that there were only thirteen, instead of the longed-for fourteen stripes, and hoped, even yet, that Canada would join.

War broke out. From the new State House, in Philadelphia, then one of the most wonderful buildings in any of the colonies, floated the flag of thirteen stripes, red and white, and independence was proclaimed.

Then, after two years, this same flag had as many stars in its blue field. Yet the armies of the Congress met with many disasters, and, one day the little girls out in the garden heard the boom of the cannon at Brandywine. It was not very long afterward, that the Continentals marched past the house, to make camp and winter quarters at Valley Forge. [22]

Among the young men riding on horses, as Washington’s body guard of young troopers, who were mostly Pennsylvania Swiss, or Germans, was John Harby’s nephew, Gustave. At the camp, besides being an orderly at headquarters, it was his special duty to raise, at sunrise, and lower, at sunset, the thirteen-striped flag, which now bore no longer the British Union Jack, but a blue field, in which, in a circle of glory, were thirteen stars; and he and his comrades rejoiced that the colonies had been made independent, and each stripe and star stood for a state, and all in a union. It was his people that, first of all, spoke of Washington as the “Father of his country”; or, as the minister said, “Pater Patriæ.”

The winter of 1777–78 had nearly passed and many a skirmish, between the British foraging parties, of Hessians and red coats, and the American Colonel Sheldon’s dragoons, had taken place. One fine morning, in the spring, while Gustave was taking breakfast, with his little cousins at the Harbys, all were startled by the firing of guns at Valley Forge. Evidently the Continentals were busy burning powder, but why?

“A battle?” asked the mother as she glanced at her husband.

At the first roll of the echoes, the young [23]trooper, Gustave, put on his bearskin cap, seized his carbine, and rushed out to hear. Putting his ear to the ground, he made up his mind that the reports were too regular for war. Then, entering the house, he declared it must be a salvo—a feu de jeu—or joy volley.

“For what, I wonder,” asked Mrs. Harby.

“I know,” said Daddy. “We have been waiting for news of the alliance with France. Now, our Continentals and the sparkling Bourbonnieres will march together. Whole companies, among these, are our Swiss boys.” Then he hummed, joyfully, the old German tune of Yankee Doodle. Perhaps now, a French fleet would come up the Delaware, blockade Philadelphia, and capture Howe’s army, as Burgoyne had been captured. At the table, they kept on talking a long time.

Only a few days later, a line of wagons, driven up from a southern port, brought in supplies from France. Five of the wagons contained saddles, bridles, stirrups and a full equipment, made in France, for the whole regiment of Colonel Sheldon’s cavalry, which had been at first raised in Connecticut. This was Lafayette’s own gift, and had been paid from out of his own purse. The Continental Congress had given him a commission in the American army, with the rank of Major-General. [24]

“Why, that sounds like a prince,” murmured little Sarah to herself.

A few days later, and another surprise broke the monotony of life at Barren Hill. Washington wished to know what the British in Philadelphia were going to do. Would they attack him? Or, considering his military position too strong to risk assault, would they retire to New York? Would Washington capture, or be captured?

So May 18, 1778, the commander-in-chief, who trusted the young French nobleman, as fully as he would trust his oldest general, placed twenty-two hundred of his best soldiers and five cannon under his charge. He was to reconnoitre, as the French say. So Lafayette led his force out, and took up to a strong position on Barren Hill.

This movement was quickly known in Philadelphia, and at once three columns of British and Hessians marched to entrap and capture Lafayette and the Continentals.

All this is national history. Yet it was like a fairy tale to the little Harby maids, Sarah and Hannah, to see the Continental soldiers, now so proud of their drilling, during the long winter, by Baron Steuben. Father Hess, the night before, had sent to the nobleman from over the great sea, an invitation to breakfast. You may [25]be sure that Mrs. Harby got out her best gold-rimmed China cups and saucers, and her caraway-seed cakes, her Zurich cookies, and her best “Dutch cake,” and silver teapot, to set before the real, live Marquis. When she told her two small daughters that she would let them wait on the young nobleman, they clapped their hands for joy. At last, they were to see, not, indeed, a prince, but a nobleman who had been at Court, talked with the mighty monarch, and who had a bride and a chateau in France.

The little girls, as they brought Lafayette his food, noticed his deep red hair, his fine forehead, his pleasing mouth and firm chin, but, most of all, his clear hazel eyes. More than once, he smiled his thanks, and this was what they, long afterward, told most about. In fact, the great man’s features seemed to bespeak strength, more than beauty; but this was what all the Harbys liked.

Did the British capture Lafayette? Did he show fear, when Gustave Hess, the scout, rode up and told of three columns of red coats marching by different roads? Two were on one side of the Schuylkill river, and one on the other. Surely, with their five thousand men, they would, as they fully expected, trap the Marquis; and, they might even bag his whole force. A ship was actually waiting in the Delaware river to take [26]the young Frenchman a captive to London. Indeed, Lord Howe had invited some handsome Tory ladies to dinner, expecting to outwit Washington and to have the young Frenchman to sit as guest and captive.

But the young general spoiled this game. Mounting his horse, he ordered out, what military men call “false heads of columns.” This made the British, who knew not what might be behind these front files, halt, until reinforced. Then they deployed, and, bringing up their cannon, sent a round shot that smashed the axle tree of one of Lafayette’s field pieces.

Must, then, the young Frenchman abandon his gun, and face Washington, with one of his cannon lost by capture? Not he! Turning the heads of their horses, the artillery men of the Continentals drove into the Harby farm yard, drew out a wagon, lashed the dismounted cannon to the hind axle, hitched on the team, and, whipping up the steeds, the whole battery dashed toward Matson’s ford, and reached safely the camp at Valley Forge. Seven gallant American lads, in the rear guard of the young Continentals, died in the fight to save the guns for their country.

But the rest of that breakfast, and all there was in the spring house, pantry, kitchen and even in the ovens, was eaten by the hot and hungry, [27]and mad, and disappointed Hessians. The two little girls lived to tell what they had seen, and another little sister, born before the war was over, stood with them on Chestnut street in 1824, to see the Marquis de Lafayette again. He was riding in the parade and amid the general joy, when the City Troop, with their old thirteen-striped flag, of 1775, escorted the aged friend of America. And the same cannon that was saved at Barren Hill thundered welcome from its iron throat. [28]

III

THE WONDERFUL ALPINE HORN

When the little boys and girls, who read these Swiss fairy tales, grow up to be big and travel in Switzerland, they will enjoy the Alpine horn.

Nearly every shepherd lad in the mountains knows how to blow it. It is made of wood, and is about half as long as an ordinary broom. Its butt, or heavy end, rests on the ground. When a man blows a long blast, the sound, at first, when one is too near, does not seem to be very pleasing; for distance lends enchantment to the sound. But wait a moment, and listen! Far off across the valley, the strains are caught up, and sent back from the tops of the high mountains. Then it sounds as if a great choir of angels had come down from Heaven to sing glory to God, and to bring greetings to all good souls. Nowhere in all the world is there such sweet music made by echoes.

Sometimes there is a double set of echoes, like one rainbow inside of another. Then, it makes one think of a choir of little angels, that sing a [29]second time, after the first heavenly chorus has ceased.

How the Swiss people first received the Alpine horn, as a gift from the fairies, is told in the story of a faithful shepherd’s boy, named Perrod. He had to work hard all day, in tending the cows that grazed on the high mountain pastures, which the natives call the Alps. But when foreign people speak of “the Alps,” they mean the ranges of mountains themselves.

In winter, these level stretches of ground are covered with snow and ice, but by the month of June, it is warm enough for the grass and flowers to grow. Then the cowboys and cheese makers go up with their cattle. At night, Perrod, having milked the cows, skimmed the cream off the milk, hung the great caldron over the fire, and made the cheese.

By this time, that is, well into the late hours, Perrod was almost tired to death. After calling “good-night” to Luquette, his sweetheart, who lived across the valley, and hearing her greeting in answer, he climbed up the ladder, into the loft, and lay down on his bed. This was only a pile of straw, but he was asleep almost the very moment he touched it, for he was a healthy lad and the mountain air was better than medicine. It was especially good for sound sleep, and he knew he must get up early, at sunrise, to lead [30]the cows and goats out to pasture. Then the all-day concert, of tinkling bells, began.

But this night, instead of slumber, without once waking until day dawn, Perrod had closed his eyes, for only about three hours, when he heard a crackling sound, which waked him up. He thought, at first, the wind was blowing hard enough to rip off some of the bark strips from the roof of the chalet, and was tumbling down some of the heavy stones laid on to keep them in place. But when he saw the reflection, on the walls and ceiling, of a bright fire, he crawled quietly out of bed. Then he peeped down and through the cracks in the board floor, to see what was going on.

Three men were around the fire. One, the biggest fellow of the three, was hanging up the caldron on the hooks. The second piled on more wood, while the others warmed their hands in the bright blaze.

The three men were all different in appearance, the one from the other, and a queer looking lot they were. The tremendously tall man seemed to be a giant, in weight and size. His sleeves were rolled up, showing that his arms were sunburnt, until they were very dark. When he lifted up the caldron, to hang it up, or take it down, his muscles stood out like whipcords.

But the man sitting on a milking stool, at the [31]right hand side of the fireplace, was entirely different, being smaller, and with a white skin and golden hair. He had a long horn, which rested on the floor beside him.

The man on the left-hand side of the fireplace, appeared to be a woodman, or hunter. At least, he seemed to be used to the forest. Though it was pitch dark night, he knew where the wood lay, piled up under the eaves of the chalet; for, when the fire burned low, he went out doors and returned with an arm load of faggots. Then he piled up the wood, and the fire blazed, and crackled, and roared, until the boy in the loft thought the hut would be burned up, too. Yet, though he trembled at the strange sight, he was brave. He resolved not to be quiet, if the big men tried to steal his cheese, which was to be food for the family during the winter.

Just as he was wondering, whether his sisters and old daddy would have enough to eat, during the long cold winter of eight months, that was soon coming, when snow and ice covered the fields, he saw a curious thing happen. Sweet music began, such as had never met his ears before, since he was in his cradle and his mother sang to him.

It was the man with the golden hair, who seemed to be the real gentleman of the party. [32]He it was, who made the music. He first handed something to the giant, who dropped it into the caldron. Then, with his horn, he disappeared through the door. When outside, he lifted the instrument to his lips and blew a blast.

Perrod was so interested in watching the giant, that he paid little attention to the man outside, or to the sound he had made, for he saw the hunter take a bottle out of his pocket, and hand it over to the biggest fellow, who stood at the caldron over the fire. This one poured the liquid, which seemed to be blood red, into the big iron pot. Then, with a ladle, as big as a shovel, and long as a gun, he stirred vigorously. Then, three beakers, or cups were set upon the table.

By this time, the golden haired man outside had finished his blast of music, which seemed to float across the valleys down into the defiles, over the pastures, and through the wood. It grew sweeter and sweeter, as it swelled on the gentle night breeze, until all the mountains seemed to have awakened, turned into living angels and lifted up their voices. The sweet strain ended with a prolonged sad note, as if melancholy had fallen on the musicians, and then it ceased.

A strange thing happened. All the cows and goats woke up from their sleep, and one, from all directions, could hear the tinkling of their neck [33]bells, all over the pastures, far and near. The poor creatures thought it was time to get up and be milked, but they were puzzled to find it was yet dark. In fact, they were all, still, quite sleepy and very slow to move.

Something even far more wonderful happened next. Perrod, after first hearing the horn blow, thought the music had ceased: when, suddenly, it all seemed to come back in vastly greater volume. The sounds were multiplied, as if a thousand echoes had blended into one and all heaven had joined in the melody. Perrod was entranced. He even closed his eyes lest he might, by looking down at the strange men, lose some of what seemed to him a choir of angels singing.

When the last strain had ceased, Perrod opened his eyes. The golden haired musician had re-entered the chalet, and resumed his seat, sitting down again on the milkstool, at the right of the fire; while the hunter rearranged three glass goblets, on the rough wooden table, from which Perrod ate his meals.

All three of the strangers then solemnly watched the caldron, as the liquid boiled, just as the cream does, when cheese is to be made; the big man stirring up with his huge ladle. At a particular moment, the giant lifted the caldron and emptied out the contents into the three glass vessels. To the amazement of Perrod, there [34]issued, from the same vessel, three very different colors.

In the first glass, filled to the brim, the draught was as red as blood, and it foamed at the top. The drops, flying out on the board, left crimson stains.

Giving a tap on the caldron, with the big ladle, the tall man let flow, into the second glass, what seemed to be the same liquid; but this time, it was as green as grass, but hissing hot, and bubbling.

Another loud ladle tap on the caldron, and out flowed a stream as cold as snow water, and as white as the edelweiss flower. The liquid rested in the goblet as quiet as milk, but seemed to be frosty on the top.

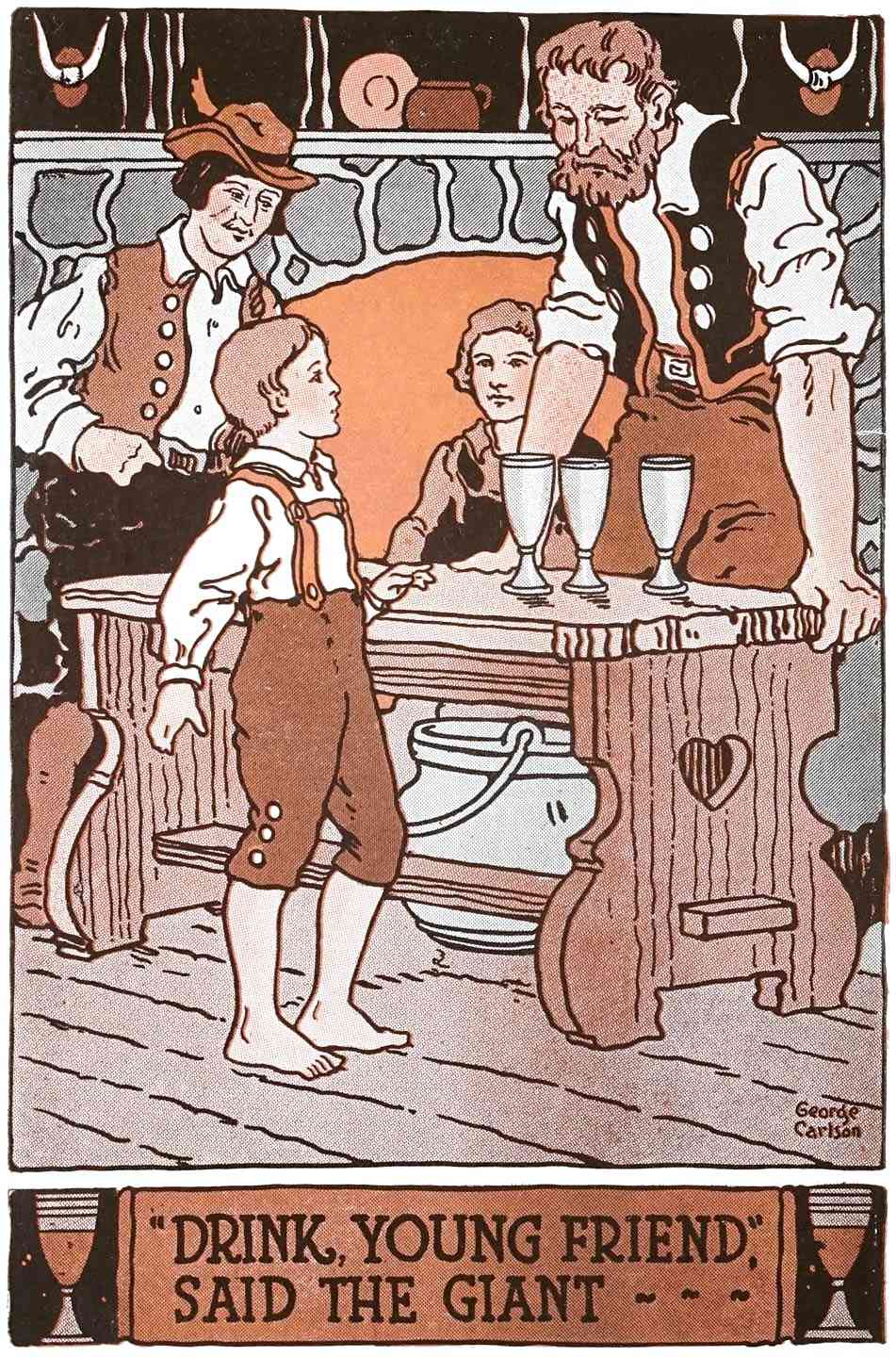

Now the giant-like fellow, shaking his huge ladle in his right hand, and putting his left at the side of his mouth, shouted with a voice of thunder:

“Come down, you boy, and make your choice of one of these three. Each has a glorious gift to him who drinks. Come quick, for it will soon be daylight.”

Perrod knew he was discovered, but he was a brave boy. If his legs trembled, his heart was big. Moreover, the golden haired man gave him a nod, and winked his eye, to encourage the lad.

So Perrod at once climbed down and stood [35]before the table, on which were the three chalices.

“Drink, young friend,” said the giant, “from any one of these, but know that, in the red liquid, is a gift to the Swiss men. Drain this cup, and then you will have strength, like me.” At that, he bent his arm to show his mighty muscles. “You will be able to conquer the strongest man, or fiercest beast. Besides, I shall give you a hundred fat cows, each of which will yield much milk, rich in butter. Drain this cup, and, according to my promise, you will see the kine tomorrow.”

Then the hunter spoke: “Better drink from my goblet. After this green draught, you will have all the gold you want, and heaps of coins; and then you can marry, and still easily support your old father and mother.” So saying, he tossed handfuls of gold pieces on the floor, piling them up, until they reached the lad’s knees. Perrod opened his eyes wide in astonishment, for here was not a promise in words, but the actual thing, that he could see for himself.

He was just about to stretch both his hands and drink the green liquid, when the golden haired man, speaking gently to Perrod, said:

“I cannot promise you either cows or coins, but if you drink the liquid in the white goblet, you will be able to use this horn, make music in the mountains and call your cows, as I have [36]done. Thus your flocks and herds also will share with you my gift.”

Not a minute did Perrod wait to decide. “I care more for music, than for money, or strength,” he said, and, lifting the glass, he put it to his lips and drained the cup dry.

“What was it, and how did it taste?” do you ask? It was what the cows gave him every day—pure fresh milk, but cold as glacier water.

“Good,” cried the man with the golden hair. “Any other choice would have meant death. Here is the horn. Blow it tomorrow, and see what will happen.”

As if lifted up on wings, to his straw bed, but holding on to his horn, Perrod heard the door shut and bang, as the three men went out, two of them scowling. Then the fire cooled to ashes. He fell asleep and dreamed of the time when, in the church, he should lead his bride to the altar, his lovely sweetheart, Luquette, to be married, and the two should have a chateau and home of their own.

Awakening at the first moment, when the rosy light of the rising sun made the face of the mountains blush, even while the valleys below were still in darkness, and long before his sisters, in the village, far away, had awakened, he rushed out to the edge of the pasture. Then, he drew in a man’s breath, filled his lungs, and, putting [37]his lips to the mouthpiece of the horn, blew a long blast. He listened eagerly, for the far off echoes. A pleasant double surprise awaited him.

All over the pastures, in the chalets of the high plateau, and along the mountain slopes, even down to the valleys, there was heard, at once, the tinkling of goat bells, cow bells, and the sound even of what hung in the metal collars of donkeys and horses, until the chorus of bell music was wonderful.

“Very fine, but is that all?” thought Perrod.

But another surprise! From across the great ravine, or chasm, out rushed his beloved Luquette. Hastily throwing a wrap around her shoulders, she stood in bare feet, threw a kiss to Perrod, and shouted to him her joy.

Now came the crowning wonder. From the high peaks, miles distant, and now rosy red in the dayspring, came back the music, in multiplied echoes, as if all the snow ranges of the Alps were singing. Pure, sweet, prolonged, the boy thought of what he had heard read in the church, that, at creation “the morning stars sang together.” So it seemed now to him.

Through many centuries, and to this day, to call the cows together, to make the goats look up, and turn homeward, to seek shelter of the night, for men’s evening prayer and chant of thanks-giving, for the signals of defence [38]against enemies, for beginning the festal dance, or, to sound the wedding joy, the Alpine horn is the delight of the Swiss. It is like the carillons of the Belgic folk, the chimes of Normandy, the tower music of Holland, or the bagpipes of the Highlander. In a foreign land, in dreams, in its memories it tells of “home, sweet home.” [39]

IV

THE WHIMSICAL AVALANCHE

It may happen, in Switzerland, that mighty masses of snow and ice, sometimes as big as the capitol at Washington, and as high as Bunker Hill monument, will roll down the mountain sides without giving any notice. These crush whole forests, bury villages, tear rocks to pieces, knock off bits of the mountain sides and kill thousands of people, cows, goats and horses.

Though large enough to engulf an army, or a battleship, they are very small, when first born, up in the very high Alps.

Starting as a snow ball, they grow large, very quickly, every moment, and finally become immense. Then, they roll along over many miles, carrying destruction in their path, until they tumble over precipices, or reach low land that is level. That is the reason why they are so named, for avalanche means “to the valley.”

There are many causes of an avalanche and a little thing may start one of these terrors. The irregular melting, by the morning sun, of ice, [40]in light or shade, the fall of an icicle, the tumbling of a stone, or a sliver of rock, or even the firing of a gun, which shakes the overhanging, or piled up snow, will begin one of these revolving globes.

Now in old times, all Swiss folk used to think that an avalanche was alive, and was having a jolly time, enjoying itself, when sliding and rolling, leaping and dashing down the mountain slopes, in its mad race, from the sky to the plain. This was its way of enjoying itself, with a short life and a merry one. It grew faster than anything else known. For, while a glacier might take a thousand years to develop, from snowflakes into miles of solid ice, like a frozen river, it required only a few minutes for an avalanche to spring from babyhood into full size, with a power exceeding that of a thousand giants.

Being, at its birth, only an inch or two in diameter, this infant son of the King of the Frost Giants, the avalanche soon became the child, which, as it grew up, so terribly fast, took after its daddy. It liked to flatten out trees, and houses, and smash things. It generally so frightened men, dogs, cats and the big animals, that dared to come near the everlasting heights of ice and snow, where the Frost Giants lived, that, in old times, no one in winter went up to the high peaks.

“DRINK YOUNG FRIEND,” SAID THE GIANT

[41]

As a rule, nobody knows, either in summer or winter, just when the avalanches will fall, or whether they will be made of light, powdery, dry snow, or of snow that is heavy, wet, and like what the boys call “soakers.” Yet there are some old men in Switzerland, who can foretell avalanches, as our wise men try to do with the weather.

Once upon a time, the Frost Giant’s baby, of which we are going to tell, was born, and great things were expected of it, even when it was only as big as a snowflake. But, when it grew up, to be a real avalanche, it behaved very differently from all the others. It disappointed its daddy and its uncles awfully. The Frost Giants like to make all the mischief they can, while this one wanted to help men, instead of hurting them, and made a new record in the history of colossal snowballs.

It was on a summer’s day, when the Frost Giants all gathered together on a big mountain top, to celebrate the birthday of their king. On his part, he was to treat them to a sight of an unusually wonderful baby. It was to be in the form of a ball of snow, that, when it become a mighty mass, would wipe out one great forest, two big villages, with all the people and cattle in it, and then roll into the valley. There it would destroy hundreds of acres of farms and [42]vineyards, block up the roads, multiply funerals, and waste so many millions of men’s dollars, that years would pass away before prosperity and good times would come again. The Frost King had a map of the route, which the young avalanche was to travel, and he showed it around freely. This was what the Frost Giants loved to do, for they hated flowers and butterflies, and cows and men.

When the white Frost Giants had come together, and all had arrived, in their coats of hard snow and with long beards of icicles, the Frost King invited them to gather at the edge of a precipice, under a jagged peak, that had many times been riven and splintered by lightning. Then he bade them look down over the landscape, while he pointed out the track which he expected his hopeful offspring, the newborn avalanche, was to take, from the time it started, until it had done its work in levelling forests, villages and vineyards. Then, using the big palm of his hand as a diagram, and his five fingers as pointers—just as a fortune teller finds out and assures a girl what kind of a husband she will have—he told them just what he was sure would happen. On reaching the valley, the big ball would spread itself over a square mile or two, while covering up and ruining the grain fields. [43]

After that, it would take the sunshine and warm south wind at least two or three years to melt the mass, while thousands of people would be in mourning for their dead children and kinsfolk. Or, reduced to beggary, they would bewail the loss of all they had in this world. To hear the old Frost King, as his tongue wagged, and the icicles of his beard flopped up and down, as the chief chin-chopper of the party, you would have thought that this baby avalanche, that was to start today was the greatest and most famous ever known.

“Now watch,” said the Frost King.

It was midday in midsummer, and the heat was great, as he took up a mass of wet snow, hardly more than a dipper full, but already made soft by the sun’s rays. He squeezed the mass hard, between the palms of his hands. To the Frost Giants, it seemed scarcely bigger than a pill.

Then, striking an attitude, like a baseball pitcher, or a man playing tenpins, and about to roll the ball along down the alley, the Frost King held up before them the dark gray, sticky ball. As he fondled and patted it, as his own child, the Frost King called out, “I name thee, my son, ‘Soaker Smash-All,’ and I expect thee to break all records. Make the widest swathe of ruin, my son, ever known among men. The sun is [44]mine enemy, and, through thee, I shall spoil his work and give him plenty of labor to restore it. Go!”

Saying this, the toss was made and the ball set rolling.

At first, for several seconds, with Soaker Smash-All, it was more like ploughing, than rolling its way through the drifts, for the slope was slight. Then, as the incline grew more steep, the tumbling became more rapid, until about a half mile from the starting point, the baby avalanche had, by its leaps and bounds grown so fast, as to be already as big as a barn. It was bouncing swiftly along, when, instead of going straight ahead, as its daddy, the Frost King, had planned and expected, it rolled against a rounded rock, that curved up and backwards, like the dashboard of a sleigh, or the roof of a pagoda.

At once, it swerved to the right and bounded high up in the air, as though some Frost Giant was playing foot ball, and was trying to hit the goal.

Then all sorts of funny things began to happen.

The Frost Giants were terribly disappointed at seeing their pet mount up in the air like a pigskin ball from the foot of a first class kicker, even before it was half grown. To behave so differently, from what its daddy had felt sure of, [45]and told the Frost Giants it would do, seemed like disobedience. For, was not this avalanche the Frost King’s son? Instead of rolling straight down the valley, gathering force for its final plunge, at every yard, it was apparently trying to climb up to the moon.

“That youngster is altogether too smart,” whispered one old giant to another.

Just a second or two, before this baby avalanche seemed to have lost both its head and its path, to go aside and play in the deep valley below, there was a hunter, on one side of the ravine, who had climbed up the high rocks, to get a shot at a herd of chamois that were feeding quietly on the other side.

Besides the buck or daddy chamois there were four mothers, each with a pretty little kid, hardly two months old, beside her. Now it was not the season for hunting, and it was against the law, which allowed the mother chamois a quiet interval, and the kids, time to grow up; for a chamois kid needs to be educated just as a child does.

But this fellow, named Erni, was both cruel and lawless. He had brought his spy glass with him and, pulling it out, swept the distant faces of the great cliffs to find his game. Just as this promising family—a buck, with a harem of four does, and as many kids—hove in sight, his fancy was tickled. Law or no law, he would shoot. [46]He laid down his glass, pointed the rifle and took cool aim, hoping to bring down two of the chamois at a shot. Then he pulled the trigger. With that gun, it was a case of “a fire at one end and a fool at the other.”

Alas, for human hopes! There is many a slip between muzzle and game. In his case a miss was as good as a mile, or even a league. In the cruel hunter’s brain there had been already a flitting vision of venison pot-pie and chamois steak. He even saw, in his day dream, two fine pairs of mounted horns adorning his parlor walls.

But the daddy of the chamois family had, a second before, thrown up his nose and caught a whiff of some human being near. Looking up in alarm, he saw the huge snow ball in the air above him. Giving the usual sort of whistle, as chamois sentinels do, the whole family started to run, as if racing with the wind, to get under the shelter of an overhanging rock.

Already the bullet had sped, and, despite their speed, one or two chamois might have fallen, but the movement of an avalanche had so thickened and condensed the air, that it was like firing a pellet of lead into molasses, making the ball go slowly. This was what is called “the wind of the avalanche,” which sometimes kills men and beasts.

Instead of the heart of a chamois, the rifle [47]bullet struck the monster snowball in the centre, but it hurt the avalanche no more than a flea bite on the end of an elephant’s tail.

We cannot here tell what Erni, the enraged hunter, said.

Having lost the whole day in climbing and now, tired, hungry and vexed with disappointment, he trudged back. When he reached home, his wife kept quiet, his children had to keep away from him, and he did not say his prayers that night.

On the contrary, in the forest home of the chamois, there was much rejoicing, for they had heard the ring of the rifle and seen its flash. In fact, avalanches were very popular in chamois society, for even when one was seen coming, soon enough, the bucks and does could easily dodge them. [48]

V

THE MOUNTAIN GIANTS

Long ages ago, when the round earth was being shaped, and the ice was melting, to give way to the green fields and flowers, huge monsters, bears, wolves and other wild animals were the only living creatures in Switzerland. Then the giants arrived on the world.

When, by and bye, human beings came into the land, they told their children that the mountains were what were left of the earth’s crust, after it had shrunk into peaks and ridges, humps and hollows, like an apple, when baked in the oven, making crusts, points and wrinkles. The valleys had been sunk, by the giants walking about on the earth, while it was yet soft. The rivers were formed by the weeping of the giants’ wives and daughters, when they were badly treated; for these rough fellows, husbands and brothers, did not know how to be kind to their female kin. The only way the giants were able to make their women obey them, when they were bad tempered, or naughty, or scolded too much, was to use shovels, pokers, clubs, and [49]straps on them. This clumsy and cruel way, of keeping the family in order, was because the giants had not yet learned to love, but were like brutes and knew only about force.

These giants, though so big, were very stupid, as compared with men. Their brains were more like those of babies, and they were not half as smart as boys and girls are to-day. They did not know enough even to plough the ground, and raise wheat, and rye, and oats, and to make porridge, to say nothing of bread and cakes, and pies and doughnuts. They could not melt lead, or work iron, or make tools, but depended on their muscles, because these were huge and tough, so that they bulged out; for the giants had terrific strength, like bulls and elephants. Though their brains were so small, their limbs were like pillars, much thicker than piano legs, and their arms were like iron. They could only make hammers, or chisels, knives and scrapers of stone, and clubs of wood, for they knew no better, and never went to school or college.