Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving

Bram Stoker

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

These Memoirs, written in an easy flowing style, give the story of the early life and struggles of this celebrated actress down to the time when her genius was recognised in every civilised country and she became her own manageress.

Sarah Bernhardt’s Memoirs are not merely an assembly of the stage stories of the most successful actress of modern times; they are the faithful record of a most interesting life—a life full of varied experiences—the reflections of a supremely intelligent mind, the story of a woman whose reminiscences alone of the celebrities she came into contact with, throw a vivid side-light on the history of the past fifty years.

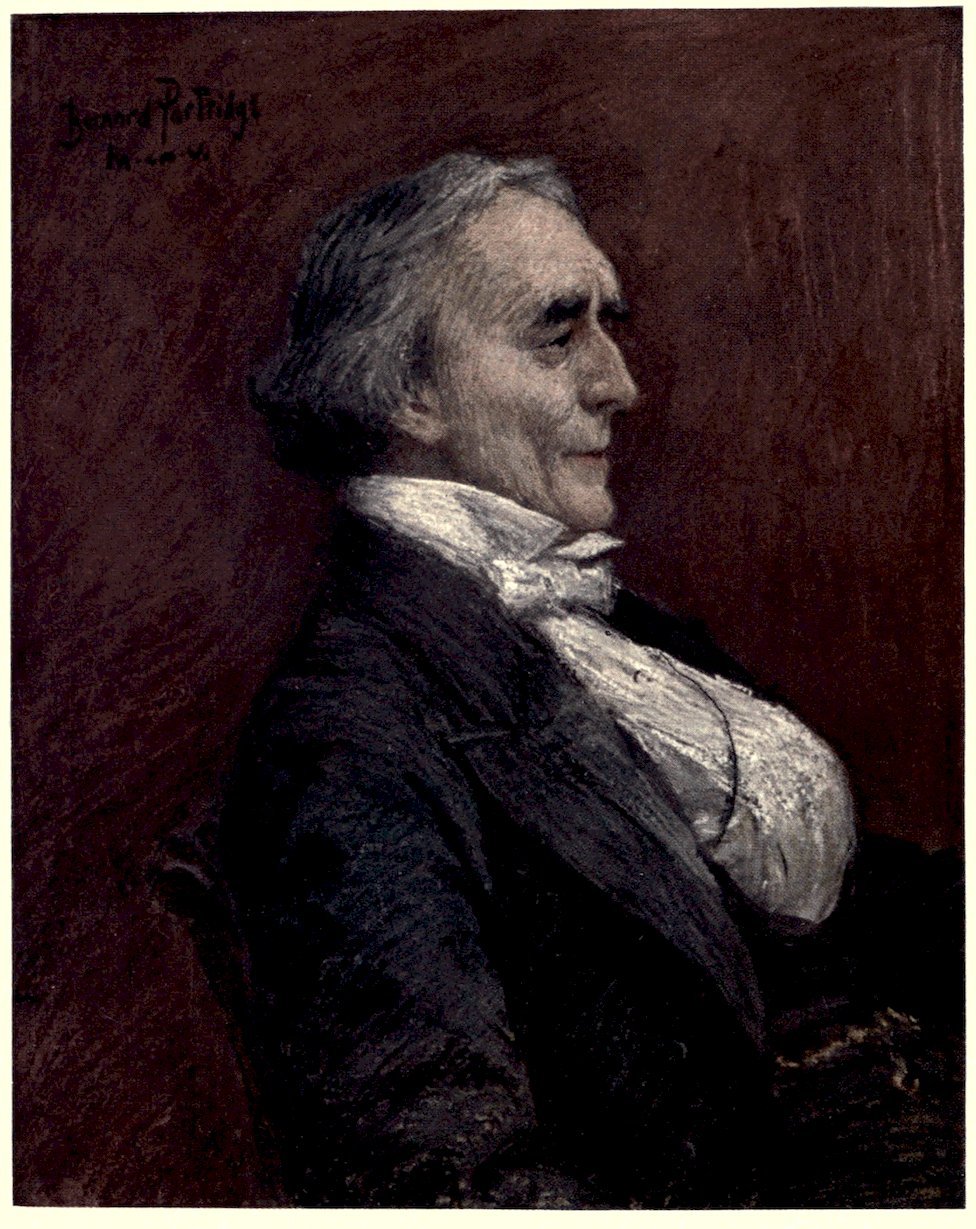

THE LAST PICTURE PAINTED OF HENRY IRVING

FROM A PASTEL

By J. BERNARD PARTRIDGE

(IN THE POSSESSION OF THE AUTHOR)

PERSONAL

REMINISCENCES

OF

HENRY IRVING

PREFACE

Were my book a “life” of Henry Irving instead of a grouping of such matters as came into my own purview, I should probably feel some embarrassment in the commencement of a preface. Logically speaking, even the life of an actor has no preface. He begins, and that is all. And such beginning is usually obscure; but faintly remembered at the best. Art is a completion; not merely a history of endeavour. It is only when completeness has been obtained that the beginnings of endeavour gain importance, and that the steps by which it has been won assume any shape of permanent interest. After all, the struggle for supremacy is so universal that the matters of hope and difficulty of one person are hardly of general interest. When the individual has won out from the huddle of strife, the means and steps of his succeeding become of interest, either historically or in the educational aspect—but not before. From every life there may be a lesson to some one; but in the teeming millions of humanity such lessons can but seldom have any general or exhaustive force. The mere din of strife is too incessant for any individual sound to carry far. Fame, who rides in higher atmosphere, can alone make her purpose heard. Well did the framers of picturesque idea understand their work when in her hand they put a symbolic trumpet.

The fame of an actor is won in minutes and seconds, not in years. The latter are only helpful in the recurrence of opportunities; in the possibilities of repetition. It is not feasible, therefore, adequately to record the progress of his work. Indeed that work in its perfection cannot be recorded; words are, and can be, but faint suggestions of awakened emotion. The student of history can, after all, but accept in matters evanescent the judgment of contemporary experience. Of such, the weight of evidence can at best incline in one direction; and that tendency is not susceptible of further proof. So much, then, for the work of art that is not plastic and permanent. There remains therefore but the artist. Of him the other arts can make record in so far as external appearance goes. Nay, more, the genius of sculptor or painter can suggest—with an understanding as subtle as that of the sun-rays which on sensitive media can depict what cannot be seen by the eye—the existence of these inner forces and qualities whence accomplished works of any kind proceed. It is to such art that we look for the teaching of our eyes. Modern science can record something of the actualities of voice and tone. Writers of force and skill and judgment can convey abstract ideas of controlling forces and purposes; of thwarting passions; of embarrassing weaknesses; of all the bundle of inconsistencies which make up an item of concrete humanity. From all these may be derived some consistent idea of individuality. This individuality is at once the ideal and the objective of portraiture.

For my own part the work which I have undertaken in this book is to show future minds something of Henry Irving as he was to me. I have chosen the form of the book for this purpose. As I cannot give the myriad of details and impressions which went to the making up of my own convictions, I have tried to select such instances as were self-sufficient to the purpose. If here and there I have been able to lift for a single instant the veil which covers the mystery of individual nature, I shall have made something known which must help the lasting memory of my dear dead friend. In the doing of my work, I am painfully conscious that I have obtruded my own personality, but I trust that for this I may be forgiven, since it is only by this means that I can convey at all the ideas which I wish to impress.

As I cannot adequately convey the sense of Irving’s worthiness myself, I try to do it by other means. By showing him amongst his friends, and explaining who those friends were; by giving incidents with explanatory matter of intention; by telling of the pressure of circumstance and his bearing under it; by affording such glimpses of his inner life and mind as one man may of another. I have earnestly tried to avoid giving pain to the living, to respect the sanctity of the dead; and finally to keep from any breach of trust—either that specifically confided in me, or implied by the accepted intimacy of our relations. Well I know how easy it is to err in this respect; to overlook the evil force of irresponsible chatter. But I have always tried to bear in mind the grim warning of Tennyson’s bitter words:

For nearly thirty years I was an intimate friend of Irving; in certain ways the most intimate friend of his life. I knew him as well as it is given to any man to know another. And this knowledge is fully in my mind, when I say that, so far as I know, there is not in this book a word of his inner life or his outer circumstances that he would wish unsaid; no omission that he would have liked filled.

Let any one who will read the book through say whether I have tried to do him honour—and to do it by worthy means: the honour and respect which I feel; which in days gone I held for him; which now I hold for his memory.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| I. | Earliest Recollections of Henry Irving | 1 | |

| Earliest recollection, Dublin, 1867—Captain Absolute—Impersonation—Distinction—Local criticism—“Two Roses,” Dublin, 1871—The archetype of Digby Grant—Chevalier Wikoff. | |||

| II. | The Old School and the New | 8 | |

| Irving’s early experience in Dublin—A month of hisses—The old school of acting and the new—Historical comparison—From Edmund Kean to Irving—Irving’s work—The thoughtful school. | |||

| III. | Friendship | 16 | |

| Criticism—My meeting with Irving—A blaze of genius—The friendship of a life. | |||

| IV. | Honours from Dublin University | 22 | |

| Public Address—University Night—Carriage dragged by students. | |||

| V. | Converging Streams | 27 | |

| A reading in Trinity College—James Knowles—Hamlet the Mystic—Richard III.—The Plantagenet look—“Only a commercial”—True sportsmen—Coming events. | |||

| VI. | Joining Forces | 35 | |

| “Vanderdecken”—Visit to Belfast—An Irish bull—I join Irving—Preparations at the Lyceum—The property master “getting even.” | |||

| VII. | Lyceum Productions | 45 | |

| VIII. | Irving Begins Management | 46 | |

| The “Lyceum Audience”—“Hamlet”—A lesson in production—The Chinese Ambassador—Catastrophe averted—The responsibility of a manager—Not ill for seven years. | |||

| IX. | Shakespeare Plays—I | 53 | |

| “The Merchant of Venice”—Preparation—The red handkerchief—Booth and Irving—“Othello”—A dinner at Hampton Court—The hat. | |||

| X. | Shakespeare Plays—II | 59 | |

| “Romeo and Juliet”—Preparation—Music—The way to carry a corpse—Variants of the bridal chamber—“Much Ado About Nothing”—John Penberthy—Hyper-criticism—Respect for feelings. | |||

| XI. | Shakespeare Plays—III | 68 | |

| “Macbeth”—An amateur scene-painter—Sir Arthur Sullivan—A lesson in collaboration—“Henry VIII.”—Lessons in illusion—Stage effects—Reality v. scenery—A real baby and its consequences. | |||

| XII. | Shakespeare Plays—IV | 76 | |

| “King Lear”—Illness of Irving—A performance at sight—“Richard III.”—A splendid first night—A sudden check. | |||

| XIII. | Irving’s Method | 82 | |

| “Eugene Aram”—Sudden change—“Richelieu”—Impersonation fixed in age—“Louis XI.”—“Up against it” in Chicago—“The Lyons Mail”—Tom Mead—Stories of his forgetfulness—“Charles I.”—Dion Boucicault on politics in the theatre—Irving’s “make-up”—Cupid as Mephistopheles. | |||

| XIV. | Art-Sense | 91 | |

| “The Bells”—Worn-out scenery—An actor’s judgment of a part—“Olivia”—“Faust”—A master mind and good service—A loyal stage manager and staff—Whistler on business—Twenty-fifth anniversary of “The Bells”—A presentation—A work of art—“The Bells” a classic—Visit of illustrious Frenchmen—Sarcey’s amusement. | |||

| XV. | Stage Effects | 101 | |

| “The Lady of Lyons”—A great stage army—Supers: their work and pay—“The Corsican Brothers”—Some great “sets”—A Royal visitor behind scenes—Seizing an opportunity—A Triton amongst minnows—Gladstone as an actor—Beaconsfield and coryphées—A double—A cure for haste. | |||

| XVI. | The Value of Experiment | 112 | |

| “Robert Macaire”—A great benefit—“Our genial friend Mr. Edwards”—“Faust”—Application of science—Division of stage labour—The Emperor Fritz—Accidental effects—A “top angel”—Educational value of the stage—“Faust” in America—Irving’s fiftieth birthday. | |||

| XVII. | The Pulse of the Public | 120 | |

| “Ravenswood”—Delayed presentation—The public pulse—“Nance Oldfield”—Ellen Terry as a dramatist. | |||

| XVIII. | Tennyson and his Plays—I | 128 | |

| Irving on Tennyson—Frankness—Irving’s knowledge of character—The “fighting” quality—Tennyson on Irving’s Hamlet—Tennyson’s alterations of his work—As a dramatist—“First run”—Experts on Greek Art. | |||

| XIX. | Tennyson and his Plays—II | 136 | |

| Before “Becket”—Irving’s preparation of the play—Re “Robin Hood”—Visit to Tennyson at Aldworth—Tennyson’s humour—His onomatopœia—Scoffing—Tennyson’s belief—He reads his new poem—Voice and phonograph—Irving sees his way to playing “Becket.” | |||

| XX. | Tennyson and his Plays—III | 146 | |

| “Becket” for the stage—My visit to Farringford—“In the Roar of the Sea”—Tennyson on “interviewers”—Relic hunters—“God the Virgin”—The hundred best stories—Message to John Fiske—Walter Map—Last visit to Tennyson—Tennyson on Homer and Shakespeare—His own reminiscences—Good-bye. | |||

| XXI. | Tennyson and his Plays—IV | 156 | |

| “Becket” produced—Death of Tennyson—“Irving will do me justice”—“The Silent Voices”—Production of the play—Irving reads it at Canterbury Cathedral—And at the King Alfred Millenary, Winchester. | |||

| XXII. | “Waterloo”—“King Arthur”—“Don Quixote” | 161 | |

| Acquisition and production of “Waterloo”—The one man in America who saw the play—Played for Indian and Colonial troops, 1897—“King Arthur” plays—Burne-Jones and the armour—“Don Quixote” plays—A rhadamanthine decision. | |||

| XXIII. | Art and Hazard | 169 | |

| “Madame Sans-Gêne”—Size, proportions and juxtaposition—Evolution of “business”—“Peter the Great” “Robespierre”—“Dante”—The hazard of management. | |||

| XXIV. | Vandenhoff | 180 | |

| XXV. | Charles Mathews | 181 | |

| In early days—A touch of character—Mathews’ appreciation—Henry Russell—The wolf and the lamb. | |||

| XXVI. | Charles Dickens and Henry Irving | 183 | |

| XXVII. | Mr. J. M. Levy | 185 | |

| XXVIII. | Visits to America | 186 | |

| Farewell at the Lyceum—Welcome in New York, 1883—A journalistic “scoop”—Farewell. | |||

| XXIX. | William Winter | 189 | |

| XXX. | Performance at West Point | 191 | |

| A National consent—Difficulties of travel—An audience of steel—A startling finale—Capture of West Point by the British. | |||

| XXXI. | American Reporters | 195 | |

| High testimony—Irving’s care in speaking—“Not for publication”—A diatribe—Moribundity. | |||

| XXXII. | Tours-de-Force | 200 | |

| A “Hamlet” reading—A vast “bill.” | |||

| XXXIII. | Christmas | 203 | |

| Christmas geese—Punch in the green room—A dinner in the theatre—Gambling without risk—Christmas at Pittsburg. | |||

| XXXIV. | Irving as a Social Force | 204 | |

| XXXV. | Visits of Foreign Warships | 208 | |

| XXXVI. | Irving’s Last Reception at the Lyceum | 211 | |

| The Queen’s Jubilee, 1887—The Diamond Jubilee, 1897—The King’s Coronation, 1902. | |||

| XXXVII. | The Voice of England | 218 | |

| XXXVIII. | Rival Towns | 220 | |

| XXXIX. | Two Stories | 221 | |

| XL. | Sir Richard Burton | 224 | |

| A face of steel—Some pleasant suppers—Lord Houghton—Searching for patriarchs—Edmund Henry Palmer—Desert law—The “Arabian Nights.” | |||

| XLI. | Sir Henry Morton Stanley | 232 | |

| An interesting dinner—“Doubting Thomases”—The lesson of exploration—“Through the Dark Continent”—Dinner—Du Chaillu—The price of fame. | |||

| XLII. | Arminius Vambéry | 238 | |

| A Defence against torture—How to travel in Central Asia—An orator. | |||

| XLIII. | Early Reminiscence by C. R. Ford | 239 | |

| XLIV. | Irving’s Philosophy of his Art | 244 | |

| The key-stone—The scientific process—Character—The Play—Stage Perspective—Dual consciousness—Individuality—The true realism. | |||

| XLV. | The Right Hon. William Ewart Gladstone | 260 | |

| Visits to the Lyceum—Intellectual stimulus and rest—An interesting post-card—His memory—“Mr. Gladstone’s seat”—Speaks of Parnell—Visit to “Becket”—Special knowledge; its application—Lord Randolph Churchill on Gladstone—Mrs. Gladstone. | |||

| XLVI. | The Earl of Beaconsfield | 266 | |

| His advice to a Court chaplain—Sir George Elliott and picture-hanging—As a beauty—As a social fencer—“A striking physiognomy.” | |||

| XLVII. | Sir William Pearce, Bart. | 270 | |

| A night adventure—The courage of a mother—The Story of the “Livadia”—Nihilists after her—Her trial trip—How she saved the Czar’s life. | |||

| XLVIII. | Stepniak | 276 | |

| A congeries of personalities—The “closed hand”—His appearance—“Free Russia”—The gentle criticism of a Nihilist—Prince Nicolas Galitzin—The dangers of big game. | |||

| XLIX. | E. Onslow Ford, R.A. | 280 | |

| Fatherly advice—The design—The meeting—Sittings—Irving’s hands. | |||

| L. | Sir Laurence Alma-Tadema, R.A. | 284 | |

| “Coriolanus”—Union of the Arts—Archæology—The re-evolution of the toga—Twenty-two years’ delay—Alma-Tadema’s house—A lesson in care—“Cymbeline.” | |||

| LI. | Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Bart. | 289 | |

| “King Arthur”—The painter’s thought—His illustrative stories from child life. | |||

| LII. | Edwin A. Abbey, R.A. | 293 | |

| “Richard II.”—“The Kinsmen”—Artistic collaboration—Mediæval life—The character of Richard. | |||

| LIII. | J. Bernard Partridge | 298 | |

| Lyceum souvenirs—Partridge’s method—“Putting in the noses”—The last picture of Irving. | |||

| LIV. | Robert Browning | 300 | |

| Browning and Irving on Shakespeare—Edmund Kean’s purse—Kean relics—Clint’s portrait of Kean. | |||

| LV. | Walt Whitman | 302 | |

| Irving meets Walt Whitman—My own friendship and correspondence with him—Like Tennyson—Visit to Walt Whitman, 1886—Again in 1887—Walt Whitman’s self-judgment—A projected bust—Lincoln’s life-work—G. W. Childs—A message from the dead. | |||

| LVI. | James Whitcomb Riley | 313 | |

| Supper on a car—A sensitive mountaineer—“Good-bye, Jim.” | |||

| LVII. | Ernest Renan | 314 | |

| Renan and Haweis—How to converse in a language you don’t know. | |||

| LVIII. | Hall Caine | 315 | |

| A remarkable criticism—Irving and “The Deemster”—“Mahomet”—For reasons of State—Weird remembrances—“The Flying Dutchman”—“Home, Sweet Home”—“Glory and John Storm”—Irving and the chimpanzee—A dangerous moment—Unceremonious treatment of a lion—Irving’s last night at the play. | |||

| LIX. | Irving and Dramatists | 325 | |

| Difficulty of getting plays—The sources—Actor as collaborator—A startled dramatist—Plays bought but not produced—Pinero. | |||

| LX. | Musicians | 331 | |

| Boito—Paderewski—Henschel—Richter—Liszt—Gounod—Sir Alexander C. Mackenzie. | |||

| LXI. | Ludwig Barnay | 338 | |

| Meeting of Irving and Barnay—“Fluff”—A dinner on the stage—A discussion on subsidy—An honour from Saxe-Meiningen—A Grand-Ducal Invasion. | |||

| LXII. | Constant Coquelin (Ainé) | 341 | |

| First meeting of Coquelin and Irving—Coquelin’s comments—Irving’s reply—“Cyrano.” | |||

| LXIII. | Sarah Bernhardt | 343 | |

| Irving sees Sarah Bernhardt—First meeting—Supper in Beefsteak Club—Bastien Lepage—Tradition—Painting a serpent—Sarah’s appreciation of Irving and Ellen Terry. | |||

| LXIV. | Geneviève Ward | 347 | |

| When and how I first saw her—Her romantic marriage—Plays Zillah at Lyceum—“Forget me not”—Plays with Irving: “Becket”; “King Arthur”; “Cymbeline”; “Richard III.”—Argument on a “reading”—Eyes that blazed—A lesson from Regnier. | |||

| LXV. | John Lawrence Toole | 353 | |

| Toole and Irving—A life-long friendship—Their jokes—A seeming robbery—An odd Christmas present—Toole and a sentry—A hornpipe in a landau—Moving Canterbury Cathedral—Toole and the verger—A joke to the King—Other jokes—His grief at Irving’s death—Our last parting. | |||

| LXVI. | Ellen Terry | 362 | |

| First meet her—Irving’s early playing with her—His criticism—How she knighted an Attorney-General—A generous player—Real flowers—Her art—Discussion on a “gag”—The New School—Last performance with Irving—The cause of separation—Their comradeship—A pet name. | |||

| LXVII. | Fresh Honours in Dublin | 373 | |

| A public reception—Above politics—A lesson in hand-shaking—A remarkable address—A generous gift. | |||

| LXVIII. | Performances at Sandringham and Windsor | 375 | |

| Sandringham, 1889—First appearance before the Queen—A quick change—Souvenirs—Windsor, 1893—A blunder in old days—Royal hospitality—The Queen and the Press—Sandringham, 1902—The Kaiser’s visit—A record journey—An amateur conductor. | |||

| LXIX. | Presidents of the United States | 384 | |

| Chester Arthur—Grover Cleveland—A judgment on taste—McKinley—The “War Room”—Reception after a Cabinet Council—McKinley’s memory—Theodore Roosevelt—His justice as Police Commissioner—Irving at his New Year Reception. | |||

| LXX. | Knighthood | 389 | |

| Irving’s intimation of the honour—First State recognition in any country—A deluge of congratulations—The Queen’s pleasure—A wonderful Address—Former suggestion of knighthood. | |||

| LXXI. | Henry Irving and Universities | 393 | |

| Dublin—Cambridge—Glasgow—Oxford—Manchester—Harvard—Columbia—Chicago—Princeton—Learned Bodies and Institutions. | |||

| LXXII. | Adventures | 405 | |

| Over a mine-bed—Fires: Edinburgh Hotel; Alhambra, London; Star Theatre, New York; Lyceum—How Theatre fires are put out—Union Square Theatre, New York—“Fussy” safe—Floods—Bayou Pierre—How to get supper—On the Pan Handle—Train accidents; explosions; “Frosted” wheel; A lost driver—Storms at sea—A reason for laughter—Falling scenery—No fear of death—Master of himself. | |||

| LXXIII. | Burning of the Lyceum Storage | 423 | |

| Difficulty of storing scenery—New storage—A clever fraud—The fire—Forty-four plays burned—Checkmate to repertoire. | |||

| LXXIV. | Finance | 427 | |

| The protection of reticence—Beginning without a capital—An overdraft—A loan—A legacy—Expenses at commencement of management—Great running expenses—Sale to the Lyceum Company—Irving’s position with them. | |||

| LXXV. | The Turn of the Tide | 438 | |

| High-water mark—A succession of disasters—Pleurisy and pneumonia—“Like Gregory Brewster”—Future arrangements decided on—Offer from the Lyceum Company—Health failing—True heroism—Work and pressure—His splendid example—The last seven years—Time of Retirement fixed—Singing at Swansea—Farewell at Sunderland—Illness at Wolverhampton—Last performances in London—Last illness—Death—A city in tears—Lying in state—Public funeral. | |||

| Index | 467 | ||

ILLUSTRATIONS

| To face page | |

|---|---|

| Last Portrait of Irving, Pastel | Coloured Frontispiece |

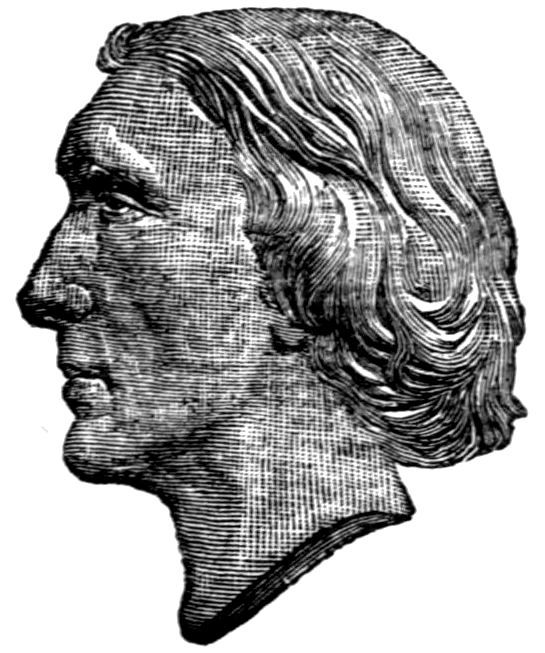

| Henry Irving before becoming an Actor | 2 |

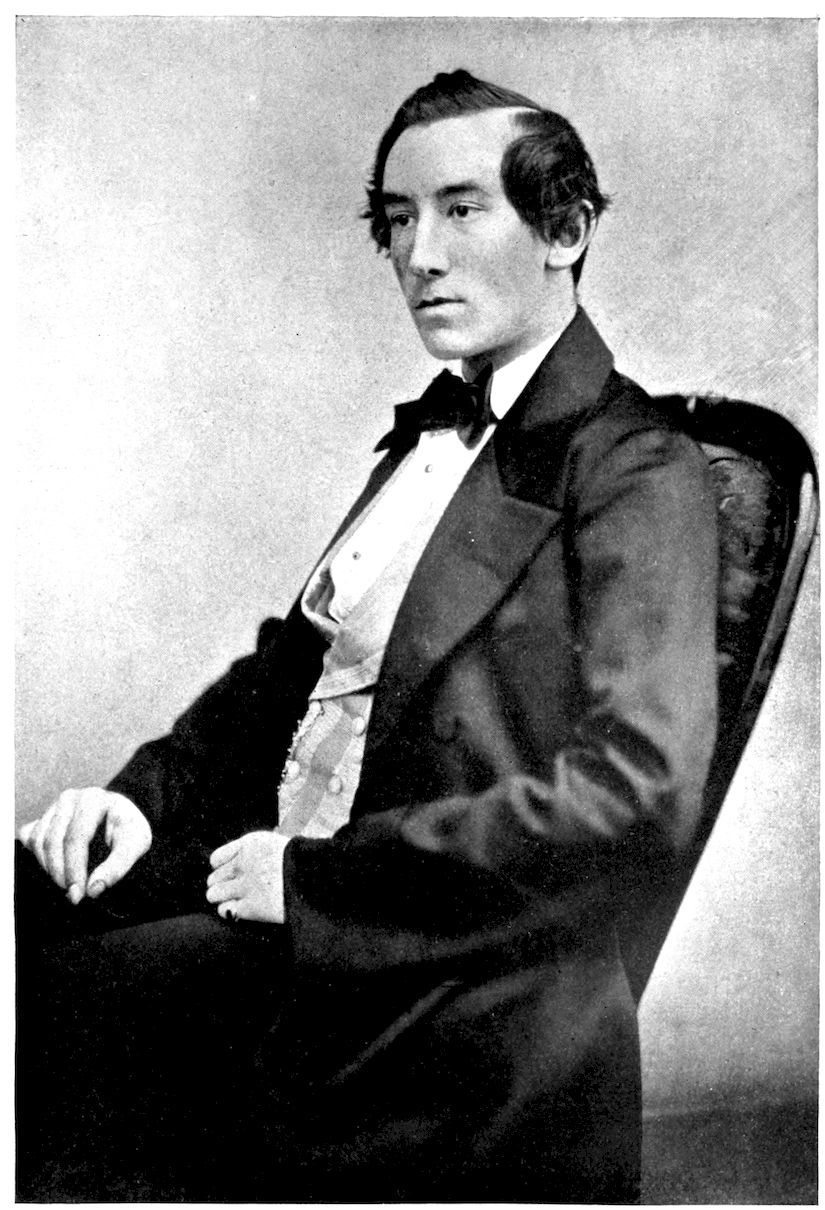

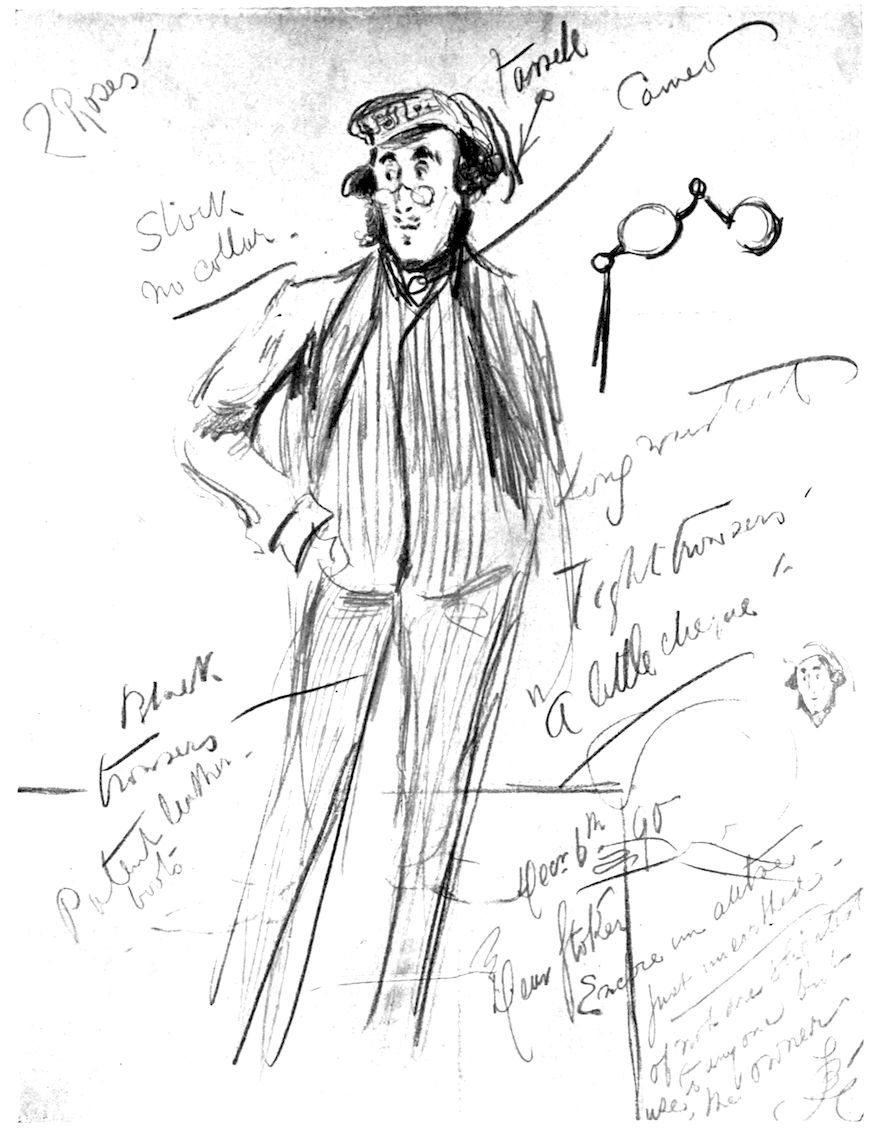

| Digby Grant. Drawing by Fred Barnard | 6 |

| Suggestion for Iago’s Dress. Drawing by Henry Irving | 58 |

| Henry Irving as Charles I. | 138 |

| Henry Irving between England and America. Drawing by Fred Barnard | 186 |

| Ellen Terry as Imogen, 1896 | 260 |

| Cast of “Dearer than Life” | 356 |

| Henry Irving and John Hare (last photograph taken) | 456 |

I

EARLIEST RECOLLECTIONS OF HENRY IRVING

I

The first time I ever saw Henry Irving was at the Theatre Royal, Dublin, on the evening of Wednesday, August 28, 1867. Miss Herbert had brought the St. James’s company on tour, playing some of the old comedies and Miss Braddon’s new drama founded on her successful novel, Lady Audley’s Secret. The piece chosen for this particular night was The Rivals, in which Irving played Captain Absolute.

Forty years ago provincial playgoers did not have much opportunity of seeing great acting, except in the star parts. It was the day of the stock companies, when the chief theatres everywhere had good actors who played for the whole season, each in his or her established class; but notable excellence was not to be expected at the salaries then possible to even the most enterprising management. The “business”—the term still applied to the minor incidents of acting, as well as to the disposition of the various characters and the entrances and exits—was, of necessity, of a formal and traditional kind. There was no time for the exhaustive rehearsal of minor details to which actors are in these days accustomed. When the bill was changed five or six times a week it was only possible, even at the longest rehearsal, to get through the standard outline of action, and secure perfection in the cues—in fact, those conditions of the interdependence of the actors and mechanics on which the structural excellence of the play depends. Moreover, the system by which great actors appeared as “stars,” supported by only one or two players of their own bringing, made it necessary that there should be in the higher order of theatres some kind of standard way of regulating the action of the plays in vogue. It was a matter of considerable interest to me to see, when some fourteen years later Edwin Booth came to play at the Lyceum, that he sent his “dresser” to represent him at the earlier rehearsals, so as to point out to the stage management the disposition of the characters and general arrangement of matured action to which he was accustomed. I only mention this here to illustrate the conditions of stage work at an earlier period.

This adherence to standard “business” was so strict, though unwritten, a rule that no one actor could venture to break it. To do so without preparation would have been to at least endanger the success of the play; and “preparation” was the prerogative of the management, not of the individual player. Even Henry Irving, though he had been, as well as a player, the stage manager of the St. James’s company, and so could carry out his ideas partially, could not have altered the broad lines of the play established by nearly a century of usage.

As a matter of fact, The Rivals had not been one of Miss Herbert’s productions at the St. James’s, and so it did not come within the scope of his stage management at all.

Irving had played the part of Captain Absolute in the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh, during three years of his engagement there, 1856–59, where he had learned the traditional usage. Thus the only possibility open to him, as to any actor with regard to an established comedy, was to improve on the traditional method of acting it within the established lines of movement; in fact, to impersonate the character to better advantage.

On this particular occasion the play as an entity had an advantage not always enjoyed in provincial theatres. It was performed by a company of comedians, several of whom had acted together for a considerable time. The lines of the play, being absolutely conventional, did not leave any special impress on the mind; one can only recall the actors and the acting.

HENRY IRVING BEFORE BECOMING AN ACTOR

1856

To this day I can remember the playing of Henry Irving as Captain Absolute, which was different from any performance of the same part which I had seen. What I saw, to my amazement and delight, was a patrician figure as real as the persons of one’s dreams, and endowed with the same poetic grace. A young soldier, handsome, distinguished, self-dependent, compact of grace and slumbrous energy. A man of quality who stood out from his surroundings on the stage as a being of another social world. A figure full of dash and fine irony, and whose ridicule seemed to bite; buoyant with the joy of life; self-conscious; an inoffensive egoist even in his love-making; of supreme and unsurpassable insolence, veiled and shrouded in his fine quality of manner. Such a figure as could only be possible in an age when the answer to offence was a sword-thrust, when only those dare be insolent who could depend to the last on the heart and brain and arm behind the blade. The scenes which stand out most vividly are the following: His interview with Mrs. Malaprop, in which she sets him to read his own intercepted letter to Lydia wherein he speaks of the old lady herself as “the old weather-beaten she-dragon.” The manner with which he went back again and again, with excuses exemplified by action rather than speech, to the offensive words—losing his place in the letter and going back to find it—seeming to try to recover the sequence of thought—innocently trying to fit the words to the subject—was simply a triumph, of well-bred, easy insolence. Again, when Captain Absolute makes repentant obedience to his father’s will his negative air of content as to the excellences or otherwise of his suggested wife was inimitable. And the shocked appearance, manner and speech of his hypocritical submission: “Not to please your father, sir?” was as enlightening to the audience as it was convincing to Sir Anthony. Again, the scene in the Fourth Act, when in the presence of his father and Mrs. Malaprop he has to make love to Lydia in his own person, was on the actor’s part a masterpiece of emotion—the sort of thing to make an author grateful. There was no mistaking the emotions which came so fast, treading on each other’s heels: his mental perturbation; his sense of the ludicrous situation in which he found himself; his hurried, feeble, ill-concealed efforts to find a way out of the difficulty. And through them all the sincerity of his real affection for Lydia which actually shone, coming straight and convincingly to the hearts of the audience.

But these scenes were all of acting a part. The reality of his character was in the scene of Sir Lucius O’Trigger’s quarrel with him. Here he was real. Man to man the grace and truth of his character and bearing were based on no purpose or afterthought. Before a man his manhood was sincere; before a gallant gentleman his gallantry was without flaw, and, as the dramatist intended, outshone even the chivalry of that perfect gentleman Sir Lucius O’Trigger.

The acting of Henry Irving is, after nearly forty years, so vivid in my memory that I can recall his movements, his expressions, the tones of his voice.

And yet the manner in which his acting in the new and perfect method was received in the local press may afford an object-lesson of what the pioneer of high art has, like any other pioneer, to endure.

During the two weeks’ visit to Dublin the repertoire comprised, as well as The Rivals, The School for Scandal, The Belle’s Stratagem, The Road to Ruin, She Stoops to Conquer, and Lady Audley’s Secret.

Of these other plays I can say nothing, for I did not see them. Lately, however, on looking over the newspapers, I found hardly a word of even judicious comment; praise there was not. According to the local journalistic record, his Joseph Surface was “lachrymose, coarse, pointless, and ineffective. Nothing could be more ludicrously deficient of dramatic power than his acting in the passage with Lady Teazle in the screen scene. The want of harmony between the actual words and gesture, emphasis and expression, was painfully palpable.”

And yet to those who can read between the lines and gather truth where truth—though not perhaps the same truth—is meant, this very criticism shows how well he played the hypocrite who meant one thing whilst conveying the idea of another. Were Joseph’s acts and tones and words all in perfect harmony he would seem to an audience not a hypocrite but a reality.

Another critic considered him “stiff and constrained, and occasionally left the audience under the impression that they were witnessing the playing of an amateur.”

The only mention of his Young Marlow was in one paper that it was “carefully represented by Mr. Irving,” and in another that it was “insipid and pointless.”

Of young Dornton in The Road to Ruin there was one passing word of praise as an “able impersonation.” But of The Rivals I could find no criticism whatever in any of the Dublin papers when more than thirty-eight years after seeing the play I searched them, hoping to find some confirmation of my vivid recollection of Henry Irving’s brilliant acting. The following only, in small type, I found in the Irish Times of more than a week after the play had been given:

“Of those who support Miss Herbert, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Matthews are undoubtedly the best. Mr. Stoyle is full of broad comedy, but now and then he is not true to nature. Mr. Irving and Mr. Gaston Murray are painstaking and respectable artists.”

It is good to think that the great player who, as the representative actor of his nation—of the world—for over a quarter of a century, was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey to the grief of at least two Continents, had after eleven years of arduous and self-sacrificing work, during which he had played over five hundred different characters and had even then begun quite a new school of acting, been considered by at least one writer for the press “a painstaking and respectable artist.”

II

I did not see Henry Irving again till May 1871, when with the Vaudeville company he played for a fortnight at the Theatre Royal Albery’s comedy Two Roses. Looking back to that time, the best testimony I can bear to the fact that the performance interested me is that I went to see it three times. The company was certainly an excellent one. In addition to Henry Irving, it contained H. J. Montague, George Honey, Louise Claire, and Amy Fawsitt.

Well do I remember the delight of that performance of Digby Grant, and how well it foiled the other characters of the play.

Amongst them all it stood out star-like—an inimitable character which Irving impersonated in a manner so complete that to this day I have been unable to get it out of my mind as a reality. Indeed, it was a reality, though at that time I did not know it. Years afterwards I met the original at the house of the late Mr. James McHenry—a villa in a little park off Addison Road.

This archetype was the late Chevalier Wikoff, of whom in the course of a friendship of years I had heard much from McHenry, who well remembered him in his early days in Philadelphia, in which city Wikoff was born. In his youth he had been a very big, handsome man, and in the days when men wore cloaks used to pass down Chestnut Street or Locust Street with a sublime swagger. He was a great friend of Edwin Forrest the actor, and a great “ladies’ man.” He had been a friend and lover of the celebrated dancer Fanny Elsler, who was so big and yet so agile that, as my father described to me, when she bounded in on the stage, seeming to light from the wings to the footlights in a single leap, the house seemed to shake. Wikoff was a pretty hard man, and as cunning as men are made. When I knew him he was an old man, but he fortified the deficiencies of age with artfulness. He was then a little hard of hearing, but he simulated complete deafness, and there was little said within a reasonable distance that he did not hear. For many years he had lived in Europe, chiefly in London and Paris. There was one trait in his character which even his intimate friends did not suspect. Every year right up to the end of his long life he disappeared from London at a certain date. He was making his pilgrimage to Paris, where on a given day he laid some flowers on a little grave long after the child’s mother, the dancer, had died. Wikoff was a trusted agent of the Bonapartes, and he held strange secrets of that adventurous family. He it was, so McHenry told me, who had brought in secret from France to England the last treasures of the Imperial house after the débâcle following Sedan.

This was the person whom Irving had reproduced in Digby Grant. Long before, he had met him at McHenry’s. With that “seeing eye” of his he had marked his personality down for use, and with that marvellous memory, which in my long experience of him never failed him, was able to reproduce with the exactness of a “Chinese copy” every jot and tittle appertaining to the man, without and within. His tall, gaunt, slightly stooping figure; his scanty hair artfully arranged to cover the ravages of time; the cunning, inquisitive eyes; the mechanical turning of the head which becomes the habit of the deaf; the veiled voice which can do everything but express truth—even under stress of sudden emotion. Years after Two Roses had had its run at the Vaudeville and elsewhere I went to see Wikoff when he was ill in a humble lodging. In answer to my knuckle-tap he opened the door himself. For an instant I was startled out of my self-possession, for in front of me stood the veritable Digby Grant. I had met him already a good many times, but always in the recognised costume of morning or evening. Now I saw him as Irving had represented him; but I do not think he had ever seen him as I saw him at that moment. I believe that the costume in which he appeared in that play was the result of the actor’s inductive ratiocination. He had studied the individuality so thoroughly, and was so familiar with not only his apparent characteristics but with those secret manifestations which are in their very secrecy subtle indicators of individuality grafted on type, that he had re-created him—just as Cuvier or Owen could from a single bone reconstruct giant reptiles of the Palæozoic age. There was the bizarre dressing-jacket, frayed at the edge and cuff, with ragged frogs and stray buttons. There the three days’ beard, white at root and raven black at point. There the flamboyant smoking-cap with yellow tassel, which marks that epoch in the history of ridiculous dress out of which in sheer revulsion of artistic feeling came the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

HENRY IRVING AS DIGBY GRANT IN “TWO ROSES”

Drawing made in his dressing-room by Fred Barnard, 1870

Irving had asked me to bring with me to Wikoff some grapes and other creature comforts, for which the poor old man was, I believe, genuinely grateful; but in the course of our chat he told me that Irving had “taken him off” for “that fellow in the Two Roses.” Wikoff did not seem displeased at the duplication of his identity, but rather proud of it.

This wonderful creation in the play “took the town,” as the phrase is, and for some time the sayings of the characters in it were heard everywhere. It was truly a “creation”; not merely in the actor’s sense, where the first player of a character in London is deemed its “creator,” but in the usual meaning of the word. For it is not enough in acting to know what to do; it must be done! All possible knowledge of Wikoff, from his psychical identity to his smoking-cap, could not produce a strong effect unless the actor through the resources of his art could transform reality to the appearance of reality—a very different and much more difficult thing.

When Irving played in Two Roses in Dublin in 1872 there was not a word in any of the papers of the acting of any of the accomplished players who took part in it; not even the mention of their names.

What other cities may have said of him in these earlier days I know not, but I take it that the standard of criticism is generally of the same average of excellence, according to the assay of the time. In the provinces the zone of demarcation between bad and good varies less, in that mediocrity qualifies more easily and superexcellence finds a wider field for work. Of one thing we may be sure: that success has its own dangers. Self-interest and jealousy and a host of the lesser and meaner vices of the intellectual world find their opportunity.

When the floodgates of Comment are opened there comes with the rush of clean water all the scum and rubbish which has accumulated behind them, drawn into position by the trickling stream.

II

THE OLD SCHOOL AND THE NEW

I

More than five years elapsed before I saw Henry Irving again. We were both busy men, each in his own way, and the Fates did not allow our orbits to cross. He did not come to Dublin; my work did not allow my going to London except at times when he was not playing there. Those five years were to him a triumphant progress in his art and fame. He rose, and rose, and rose. The Bells in 1871 was followed in 1872 by Charles I., in 1873 by Eugene Aram, and Richelieu, in 1874 by Philip and Hamlet, in 1875 by Macbeth, and in 1876 by Othello and Queen Mary.

For my own part, being then in the Civil Service, I could only get away in the “prime of summer time” as my seniors preferred to take their holiday in the early summer or the late autumn. I had, when we next met, been for five years a dramatic critic. In 1871 my growing discontent with the attention accorded to the stage in the local newspapers had culminated with the neglect of Two Roses. I asked the proprietor of one of the Dublin newspapers whom I happened to know, Dr. Maunsell, an old contemporary and friend of Charles Lever, to allow me to write on the subject in the Mail. He told me frankly that the paper could not afford to pay for such special work, as it was, in accordance with the local custom of the time, done by the regular staff, who wrote on all subjects as required. I replied that I would gladly do it without fee or reward. This he allowed me to carry out.

From my beginning the work in November 1871 I had an absolutely free hand. I was thus able to direct public attention, so far as my paper could effect it, where in my mind such was required. In those five years I think I learned a good deal. “Writing maketh an exact man”; and as I have always held that in matters critical the critic’s personal honour is involved in every word he writes, the duty I had undertaken was to me a grave one. I did not shirk work in any way; indeed, I helped largely to effect a needed reform as to the time when criticism should appear. In those days of single printings from slow presses “copy” had to be handed in very early. The paper went to press not long after midnight, and there were few men who could see a play and write the criticism in time for the morning’s issue. It thus happened that the critical article was usually a full day behind its time. Monday night’s performance was not generally reviewed till Wednesday at earliest; the instances which I have already given afford the proof. This was very hard upon the actors and companies making short visits. The public en bloc is a slow-moving force, and when possibility of result is cut short by effluxion of time it is a sad handicap to enterprise and to exceptional work.

I do not wish to be egotistical, and I trust that no reader may take it that I am so, in that I have spoken of my first experiences of Henry Irving and how, mainly because of his influence on me, I undertook critical work with regard to his own art. My purpose in doing so is not selfish. I merely wish that those who honour me by reading what I have written should understand something which went before our personal meeting, and why it was that when we did meet we came together with a loving and understanding friendship which lasted unbroken till my dear friend passed away.

Looking back now after an interval of nearly forty years, during which time I was mainly too busy to look back at all, I can understand something of those root-forces which had so strange an influence on both Irving’s life and my own, though at the first I was absolutely unconscious of even their existence. Neither when I first saw Irving in 1867, nor when I met him in 1876, nor for many years after I had been his close friend and fellow worker, did I know that his first experience of Dublin had been painful to the last degree. I thought from the way in which the press had ignored him and his work that they must have been bad enough in 1867 and 1871. But long afterwards he told me the story to this effect:

Quite early in his life as an actor—when he was only twenty-one—in an off season, when the “resting” actor grasps at any chance of work, he received from Mr. Harry Webb, then Manager of the Queen’s Theatre, Dublin, and with whom he had played at the Edinburgh Theatre, an offer of an engagement for some weeks. This he joyfully accepted; and turned up in due course. He did not know then, though he learned it with startling rapidity, that he was wanted to fill the place of a local favourite who had been, for some cause, summarily dismissed. The public visited their displeasure on the new-comer, and in no uncertain way. From the moment of his coming on the stage on the first night of his engagement until almost its end he was not allowed to say one word without interruption. Hisses and stamping, cat-calls and the thumping of sticks were the universal accompaniments of his speech.

Now to an actor nothing is so deadly as to be hissed. Not only does it bar his artistic effort, but it hurts his self-esteem. Its manifestation is a negation of himself, his power, his art. It is present death to him quâ artist, with the added sting of shame. Well did the actors know it who crowded the court at Bow Street when the vanity-mad fool who murdered poor William Terriss was arraigned. The murderer was an alleged actor, and they wanted to punish him. When he was placed in the dock, with one impulse they hissed him!

In Irving’s case at the Queen’s the audience, with some shameful remnant of fair play, treated him well the last two nights of his performance, and cheered him. It was manifestly intended as a proof that it was not against this particular man that their protest was aimed—though he was the sufferer by it—but against any one who might have taken the place of their favourite, whom they considered had been injured.

Of this engagement Irving spoke to an interviewer in 1891 apropos of an outrage, unique to him, inflicted on Toole shortly before at Coatbridge—a place of which the saying is, “There is only a sheet of paper between Hell and Coatbridge.”

“Did you ever have any similar experience in your own career, Mr. Irving?”

“... I did have rather a nasty time once, and suffered much as Mr. Toole has done from the misplaced emotions of the house. It was in this way. When I was a young man—away back about 1859” (should be 1860) “I should say it was—I was once sent for to fulfil an engagement of six weeks at the Queen’s Theatre, a minor theatre in the Irish capital. It was soon after I had left here, Edinburgh. I got over all right, and was ready with my part, but to my amazement, the moment I appeared on the stage I was greeted with a howl of execration from the pit and gallery. There was I standing aghast, ignorant of having given any cause of offence, and in front of me a raging Irish audience, shouting, gesticulating, swearing probably, and in various forms indicating their disapproval of my appearance. I was simply thunderstruck at the warmth of my reception.... I simply went through my part amid a continual uproar—groans, hoots, hisses, cat-calls, and all the appliances of concerted opposition. It was a roughish experience that!”

“But surely it did not last long?”

“That depends,” replied the player grimly, “on what you call long. It lasted six weeks.... I was as innocent as yourself of all offence, and could not for the life of me make out what was wrong. I had hurt nobody; had said nothing insulting; I had played my parts not badly for me. Yet for the whole of that time I had every night to fight through my piece in the teeth of a house whose entire energies seemed to be concentrated in a personal antipathy to myself.”

It was little wonder that the actor who had thus suffered undeservedly remembered the details, though the time had so long gone by that he made error as to the year. No wonder that the time of the purgatorial suffering seemed fifty per cent. longer than its actual duration. Other things of more moment had long ago passed out of his mind—he had supped full of success and praise; but the bitter flavour of that month of pain hung all the same in his cup of memory.

How it hung can hardly be expressed in words. For years he did not speak of it even to me when telling me of how on March 12, 1860, he played Laertes to the Hamlet of T. C. King. It was not till after more than a quarter of a century of unbroken success that he could bear even to speak of it. Not even the consciousness of his own innocence in the whole affair could quell the mental disturbance which it caused him whenever it came back to his thoughts.

II

When, then, Henry Irving came to Dublin in 1876, though it was after a series of triumphs in London running into a term of years, he must have had some strong misgivings as to what his reception might be. It is true that the early obloquy had lessened into neglect; but no artist whose stock-in-trade is mainly his own personality could be expected to reason with the same calmness as that Parliamentary candidate who thus expressed the grounds of his own belief in his growing popularity:

“I am growing popular!”

“Popular!” said his friend. “Why, last night I saw them pelt you with rotten eggs!”

“Yes!” he replied with gratification, “that is right! But they used to throw bricks!”

In London the bricks had been thrown, and in plenty. There are some persons of such a temperament that they are jealous of any new idea—of any thing or idea which is outside their own experience or beyond their own reasoning. The new ideas of thoughtful acting which Irving introduced won their way, in the main, splendidly. But it was a hard fight, for there were some violent and malignant writers of the time who did not hesitate to stoop to any meanness of attack. It is extraordinary how the sibilation of a single hiss will win through a tempest of cheers! The battle, however, was being won; when Irving came to Dublin he brought with him a reputation consolidated by the victorious conclusions of five years of strife. The new method was already winning its way.

It so happens that I was myself able through a “fortuitous concourse” of facts to have some means of comparison between the new and the old.

My father, who was born in 1798 and had been a theatre-goer all his life, had seen Edmund Kean in all his Dublin performances. He had an immense admiration for that actor, with whom none of the men within thirty years of his death were, he said, to be compared. When the late Barry Sullivan came on tour and played a range of the great plays he had enormous success. My father, then well over seventy, did not go to the play as often as he had been used to in earlier days; but I was so much struck with the force of Barry Sullivan’s acting that I persuaded him to come with me to see him play Sir Giles Overreach in A New Way to Pay Old Debts—one of his greatest successes, as it had been one of Kean’s. At first he refused to come, saying that it was no use his going, as he had seen the greatest of all actors in the part, and did not care to see a lesser one. However, he let me have my way, and went; and we sat together in the third row of the pit, which had been his chosen locality in his youth. He had been all his life in the Civil Service, serving under four monarchs—George III., George IV., William IV., and Victoria—and retiring after fifty years of service. In those days, as now, the home Civil Service was not a very money-making business, and it was just as well that he preferred the pit. I believed then that I preferred it also, for I too was then in the Civil Service!

He sat the play out with intense eagerness, and as the curtain fell on the frenzied usurer driven mad by thwarted ambition and the loss of his treasure, feebly spitting at the foes he could not master as he sank feebly into supporting arms, he turned to me and said:

“He is as good as the best of them!”

Barry Sullivan was a purely traditional actor of the old school. All his movements and gestures, readings, phrasings, and times were in exact accordance with the accepted style. It was possible, therefore, for my father to judge fairly. I saw Barry Sullivan in many plays: Hamlet, Richelieu, Macbeth, King Lear, The Gamester, The Wife’s Secret, The Stranger, Richard III., The Wonder, Othello, The School for Scandal, as well as playing Sir Giles Overreach, and some more than once; I had a fair opportunity of comparing his acting over a wide range with the particular play by which my father judged. Ab uno disce omnes is hardly a working rule in general, but one example is a world better than none. I can fairly say that the actor’s general excellence was fairly represented by his characterisation and acting of Sir Giles. I had also seen Charles Kean, G. V. Brook, T. C. King, Charles Dillon, and Vandenhoff. I had therefore in my own mind some kind of a standard by which to judge of the worth of the old school, tracing it back to its last great exemplar. When, therefore, I came to contrast it with the new school of Irving, I was building my opinion not on sand but upon solid ground. Let me say how the change from the old to the new affected me; it is allowable, I suppose, in matters of reminiscence to take personal example. Hitherto I had only seen Irving in two characters, Captain Absolute and Digby Grant. The former of these was a part in which for at least ten years—for I was a playgoer very early in life—I had seen other actors all playing the part in a conventional manner. As I have explained, I had only in Irving’s case been struck by his rendering of his own part within the conventional lines. The latter part was of quite a new style—new to the world in its essence as its method, and we of that time and place had no standard with regard to it, no means or opportunity of comparison. It was therefore with very great interest that we regarded in 1876 the playing of this actor who was accepted in the main as a new giant. To me as a critic, with the experience of five years of the work, the occasion was of great moment; and I am free to confess that I was a little jealous lest the new-comer—even though I admired so much of his work as I had seen—should overthrow my friend and countryman. For at this time Barry Sullivan was more than an acquaintance; we had spent a good many hours together talking over acting and stage history generally. Indeed, I said in my critical article thus:

“Mr. Irving holds in the minds of all who have seen him a high place as an artist, and by some he is regarded as the Garrick of his age; and so we shall judge him by the highest standard which we know.”

At the first glance, after the lapse of time, this seems if not unfair at least hard upon the actor; but the second thought shows a subtle though unintentional compliment: Henry Irving had already raised in his critic, partly by the dignity of his own fame and partly through the favourable experience of the critic, the standard of criticism. He was to be himself the standard of excellence! His present boon to us was that he had taught us to think. Let me give an illustration.

Barry Sullivan was according to accepted ideas a great Macbeth. I for one thought so. He had great strength, great voice, great physique of all sorts; a well-knit figure with fine limbs, broad shoulders, and the perfect back of a prize-fighter. He was master of himself, and absolutely well versed in the parts which he played. His fighting power was immense, and in the last act of the play good to see. The last scene of all, when the “flats” of the penultimate scene were drawn away in response to the usual carpenter’s whistle of the time, was disclosed as a bare stage with “wings” of wild rock and heather. At the back was Macbeth’s Castle of Dunsinane seen in perspective. It was supposed to be vast, and occupied the whole back of the scene. In the centre was the gate, double doors in a Gothic archway of massive proportions. In reality it was quite eight feet high, though of course looking bigger in the perspective. The stage was empty, but from all round it rose the blare of trumpets and the roll of drums. Suddenly the Castle gates were dashed back, and through the archway came Macbeth, sword in hand and buckler on arm. Dashing with really superb vigour down to the footlights, he thundered out his speech:

“They have tied me to a stake; I cannot fly.”

Now this was to us all very fine, and was vastly exciting. None of us ever questioned its accuracy to nature. That Castle with the massive gates thrown back on their hinges by the rush of a single man came back to me vividly when I saw the play as Irving did it in 1888, though at the time we had never given it a thought. Indeed, we gave thought to few such things; we took them with simplicity and as they were, just as we accepted the conventional scenes of the then theatre, the Palace Arches, the Oak Chamber, the Forest Glade with its added wood wings, and all the machinery of tradition. With Irving all was different. That “easy” progress of Macbeth’s soldiers returning tired after victorious battle, seen against the low dropping sun across the vast heather studded with patches of light glinting on water; the endless procession of soldiers straggling, singly, and by twos and threes, filling the stage to the conclusion of an endless array, conveyed an idea of force and power which impressed the spectator with an invaluable sincerity. In fact, Irving always helped his audience to think.

III

FRIENDSHIP

I

That Irving was, in my estimation, worthy of the test I had laid down is shown by my article on the opening performance of Hamlet, and in the second article written after I had seen him play the part for the third time running. That he was pleased with the review of his work was proved by the fact that he asked on reading my criticism on Tuesday morning that we should be introduced. This was effected by my friend Mr. John Harris, Manager of the Theatre Royal.

Irving and I met as friends, and it was a great gratification to me when he praised my work. He asked me to come round to his room again when the play was over. I went back with him to his hotel, and with three of his friends supped with him.

We met again on the following Sunday, when he had a few friends to dinner. It was a pleasant evening and a memorable one for me, for then began the close friendship between us which only terminated with his life—if indeed friendship, like any other form of love, can ever terminate. In the meantime I had written the second notice of his Hamlet. This had appeared on Saturday, and when we met he was full of it. Praise was no new thing to him in those days. Two years before, though I knew nothing of them at that time, two criticisms of his Hamlet had been published in Liverpool. One admirable pamphlet was by Sir (then Mr.) Edward Russell, then, as now, the finest critic in England; the other by Hall Caine—a remarkable review to have been written by a young man under twenty. Some of the finest and most lofty minds had been brought to bear on his work. It is, however, a peculiarity of an actor’s work that it never grows stale; no matter how often the same thing be repeated, it requires a fresh effort each time. Thus it is that criticism can never be stale either; it has always power either to soothe or to hurt. To a great actor the growth of character never stops, and any new point is a new interest, a new lease of intellectual life.

II

Before dinner Irving chatted with me about this second article. In it I had said:

“There is another view of Hamlet, too, which Mr. Irving seems to realise by a kind of instinct, but which requires to be more fully and intentionally worked out.... The great, deep, underlying idea of Hamlet is that of a mystic.... In the high-strung nerves of the man; in the natural impulse of spiritual susceptibility; in his concentrated action, spasmodic though it sometimes be, and in the divine delirium of his perfected passion there is the instinct of the mystic, which he has but to render a little plainer in order that the less susceptible senses of his audience may see and understand.”

He was also pleased with another comment of mine. Speaking of the love shown in his parting with Ophelia I had said:

“To give strong grounds for belief, where the instinct can judge more truly than the intellect, is the perfection of suggestive acting; and certainly with regard to this view of Hamlet Mr. Irving deserves not only the highest praise that can be accorded, but the loving gratitude of all to whom his art is dear.”

There were plenty of things in my two criticisms which could hardly have been pleasurable to the actor, so that my review of his work could not be considered mere adulation. But I never knew in all the years of our friendship and business relations Irving to take offence or be hurt by true criticism—that criticism which is philosophical and gives a reason for every opinion adverse to that on which judgment is held. When any one could let Irving believe that he had either studied the subject or felt the result of his own showing, he was prepared to argue to the last any point suggested on equal terms. I remember at this time Edward Dowden, the great Shakespearean critic, then, as now, Professor of English Literature in Dublin University, saying to me in discussing Irving’s acting:

“After all, an actor’s commentary is his acting!”—a remark of embodied wisdom. Irving had so thoroughly studied every phase and application and the relative importance of every word of his part that he was well able to defend his accepted position. Seldom indeed was any one able to refute him; but when such occurred no one was more ready to accept the true view—and to act upon it.

Thus it was that on this particular night my host’s heart was from the beginning something toward me, as mine had been toward him. He had learned that I could appreciate high effort; and with the instinct of his craft liked, I suppose, to prove himself again to his new, sympathetic and understanding friend. And so after dinner he said he would like to recite for me Thomas Hood’s poem The Dream of Eugene Aram.

That experience I shall never—can never—forget. The recitation was different, both in kind and degree, from anything I had ever heard; and in those days there were some noble experiences of moving speech. It had been my good fortune to be in Court when Whiteside made his noble appeal to the jury in the Yelverton Case; a speech which won for him the unique honour, when next he walked into his place in the House of Commons, of the whole House standing up and cheering him.

I had heard Lord Brougham speak amid a tempest of cheers in the great Round Room of the Dublin Mansion House.

I had heard John Bright make his great oration on Ireland in the Dublin Mechanics’ Institute, and had thrilled to the roar within, and the echoing roar from the crowded street without, which followed his splendid utterance. Like all the others I was touched with deep emotion. To this day I can remember the tones of his organ voice as he swept us all—heart and brain and memory and hope—with his mighty periods; moving all who remembered how in the Famine time America took the guns from her battleships to load them fuller with grain for the starving Irish peasants.

These experiences and many others had shown me something of the power of words. In all these and in most of the others there were natural aids to the words spoken. The occasion had always been great, the theme far above one’s daily life. The place had always been one of dignity; and above all, had been the greatest of all aids to effective speech, that which I heard Dean (then Canon) Farrar call in his great sermon on Garibaldi “the mysterious sympathy of numbers.” But here in a dining-room, amid a dozen friends, a man in evening dress stood up to recite a poem with which we had all been familiar from our schooldays, which most if not all of us had ourselves recited at some time.