Fables for Children and Other Stories

Leo Tolstoy

The Complete Works of

COUNT TOLSTÓY

Volume XII.

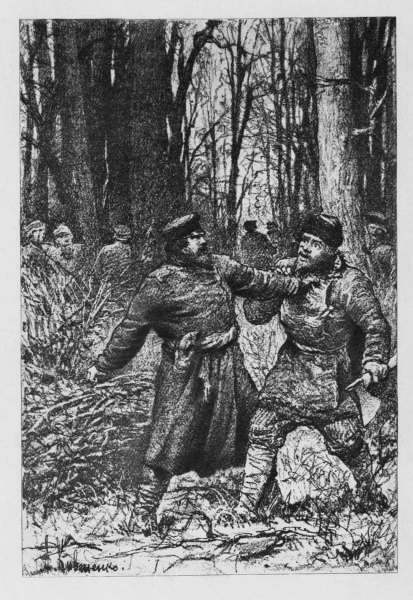

"The clerk beat Sidor's face until the blood came"

"The clerk beat Sidor's face until the blood came"

Photogravure from Painting by A. Kivshénko

FABLES FOR CHILDREN ⚘ STORIES FOR CHILDREN ⚘ NATURAL SCIENCE STORIES ⚘ POPULAR EDUCATION ⚘ DECEMBRISTS ⚘ MORAL TALES ⚘ ⚘ ⚘

By COUNT LEV N. T́OLSTÓY

Translated from the Original Russian and Edited by

LEO WIENER

Assistant Professor of Slavic Languages at Harvard University

BOSTON ⚘ DANA ESTES & COMPANY ⚘ PUBLISHERS

EDITION DE LUXE

Limited to One Thousand Copies, of which this is No. 411

Copyright, 1904

By Dana Estes & Company

Entered at Stationers' Hall

Colonial Press: Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co., Boston, Mass., U. S. A.

CONTENTS

- PAGE

FABLES FOR CHILDREN

- Æsop's Fables 3

- Adaptations and Imitations of Hindoo Fables 19

STORIES FOR CHILDREN

- The Foundling 39

- The Peasant and the Cucumbers 40

- The Fire 41

- The Old Horse 43

- How I Learned to Ride 46

- The Willow 49

- Búlka 51

- Búlka and the Wild Boar 53

- Pheasants 56

- Milton and Búlka 58

- The Turtle 60

- Búlka and the Wolf 62

- What Happened to Búlka in Pyatigórsk 65

- Búlka's and Milton's End 68

- The Gray Hare 70

- God Sees the Truth, but Does Not Tell at Once 72

- Hunting Worse than Slavery 82

- A Prisoner of the Caucasus 92

- Ermák 124

NATURAL SCIENCE STORIES

- Stories From Physics:

- The Magnet 137

- Moisture 140

- The Different Connection of Particles 142

- Crystals 143

- Injurious Air 146

- How Balloons Are Made 150

- Galvanism 152

- The Sun's Heat 156

- Stories From Zoology:

- The Owl and the Hare 159

- How the Wolves Teach Their Whelps 160

- Hares and Wolves 161

- The Scent 162

- Touch and Sight 164

- The Silkworm 165

- Stories From Botany:

- The Apple-Tree 170

- The Old Poplar 172

- The Bird-Cherry 174

- How Trees Walk 176

-

- The Decembrists 181

- On Popular Education 251

- What Men Live By 327

- The Three Hermits 363

- Neglect the Fire 375

- The Candle 395

- The Two Old Men 409

- Where Love Is, There God Is Also 445

TEXTS FOR CHAPBOOK ILLUSTRATIONS

- The Fiend Persists, but God Resists 463

- Little Girls Wiser than Old People 466

- The Two Brothers and the Gold 469

- Ilyás 472

-

- A Fairy-Tale about Iván the Fool 481

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- "The clerk beat Sídor's face until the blood came" (The Candle, see page 397) Frontispiece

- "'Whose knife is this?'" 73

- "'God will forgive you'" 81

- "They rode off to the mountains" 96

- "'Whither are you bound?'" 332

- "But the candle was still burning" 403

FABLES FOR CHILDREN

1869-1872

FABLES FOR CHILDREN

I. ÆSOP'S FABLES

THE ANT AND THE DOVE

An Ant came down to the brook: he wanted to drink. A wave washed him down and almost drowned him. A Dove was carrying a branch; she saw the Ant was drowning, so she cast the branch down to him in the brook. The Ant got up on the branch and was saved. Then a hunter placed a snare for the Dove, and was on the point of drawing it in. The Ant crawled up to the hunter and bit him on the leg; the hunter groaned and dropped the snare. The Dove fluttered upwards and flew away.

THE TURTLE AND THE EAGLE

A Turtle asked an Eagle to teach her how to fly. The Eagle advised her not to try, as she was not fit for it; but she insisted. The Eagle took her in his claws, raised her up, and dropped her: she fell on stones and broke to pieces.

THE POLECAT

A Polecat entered a smithy and began to lick the filings. Blood began to flow from the Polecat's mouth, but he was glad and continued to lick; he thought that the blood was coming from the iron, and lost his whole tongue.

THE LION AND THE MOUSE

A Lion was sleeping. A Mouse ran over his body. He awoke and caught her. The Mouse besought him; she said:

"Let me go, and I will do you a favour!"

The Lion laughed at the Mouse for promising him a favour, and let her go.

Then the hunters caught the Lion and tied him with a rope to a tree. The Mouse heard the Lion's roar, ran up, gnawed the rope through, and said:

"Do you remember? You laughed, not thinking that I could repay, but now you see that a favour may come also from a Mouse."

THE LIAR

A Boy was watching the sheep and, pretending that he saw a wolf, he began to cry:

"Help! A wolf! A wolf!"

The peasants came running up and saw that it was not so. After doing this for a second and a third time, it happened that a wolf came indeed. The Boy began to cry:

"Come, come, quickly, a wolf!"

The peasants thought that he was deceiving them as usual, and paid no attention to him. The wolf saw there was no reason to be afraid: he leisurely killed the whole flock.

THE ASS AND THE HORSE

A man had an Ass and a Horse. They were walking on the road; the Ass said to the Horse:

"It is heavy for me.—I shall not be able to carry it all; take at least a part of my load."

The Horse paid no attention to him. The Ass fell down from overstraining himself, and died. When the master transferred the Ass's load on the Horse, and added the Ass's hide, the Horse began to complain:

"Oh, woe to me, poor one, woe to me, unfortunate Horse! I did not want to help him even a little, and now I have to carry everything, and his hide, too."

THE JACKDAW AND THE DOVES

A Jackdaw saw that the Doves were well fed,—so she painted herself white and flew into the dove-cot. The Doves thought at first that she was a dove like them, and let her in. But the Jackdaw forgot herself and croaked in jackdaw fashion. Then the Doves began to pick at her and drove her away. The Jackdaw flew back to her friends, but the jackdaws were frightened at her, seeing her white, and themselves drove her away.

THE WOMAN AND THE HEN

A Hen laid an egg each day. The Mistress thought that if she gave her more to eat, she would lay twice as much. So she did. The Hen grew fat and stopped laying.

THE LION, THE BEAR, AND THE FOX

A Lion and a Bear procured some meat and began to fight for it. The Bear did not want to give in, nor did the Lion yield. They fought for so long a time that they both grew feeble and lay down. A Fox saw the meat between them; she grabbed it and ran away with it.

THE DOG, THE COCK, AND THE FOX

A Dog and a Cock went to travel together. At night the Cock fell asleep in a tree, and the Dog fixed a place for himself between the roots of that tree. When the time came, the Cock began to crow. A Fox heard the Cock, ran up to the tree, and began to beg the Cock to come down, as she wanted to give him her respects for such a fine voice.

The Cock said:

"You must first wake up the janitor,—he is sleeping between the roots. Let him open up, and I will come down."

The Fox began to look for the janitor, and started yelping. The Dog sprang out at once and killed the Fox.

THE HORSE AND THE GROOM

A Groom stole the Horse's oats, and sold them, but he cleaned the Horse each day. Said the Horse:

"If you really wish me to be in good condition, do not sell my oats."

THE FROG AND THE LION

A Lion heard a Frog croaking, and thought it was a large beast that was calling so loud. He walked up, and saw a Frog coming out of the swamp. The Lion crushed her with his paw and said:

"There is nothing to look at, and yet I was frightened."

THE GRASSHOPPER AND THE ANTS

In the fall the wheat of the Ants got wet; they were drying it. A hungry Grasshopper asked them for something to eat. The Ants said:

"Why did you not gather food during the summer?"

She said:

"I had no time: I sang songs."

They laughed, and said:

"If you sang in the summer, dance in the winter!"

THE HEN AND THE GOLDEN EGGS

A master had a Hen which laid golden eggs. He wanted more gold at once, and so killed the Hen (he thought that inside of her there was a large lump of gold), but she was just like any other hen.

THE ASS IN THE LION'S SKIN

An Ass put on a lion's skin, and all thought it was a lion. Men and animals ran away from him. A wind sprang up, and the skin was blown aside, and the Ass could be seen. People ran up and beat the Ass.

THE HEN AND THE SWALLOW

A Hen found some snake's eggs and began to sit on them. A Swallow saw it and said:

"Stupid one! You will hatch them out, and, when they grow up, you will be the first one to suffer from them."

THE STAG AND THE FAWN

A Fawn once said to a Stag:

"Father, you are larger and fleeter than the dogs, and, besides, you have huge antlers for defence; why, then, are you so afraid of the dogs?"

The Stag laughed, and said:

"You speak the truth, my child. The trouble is,—the moment I hear the dogs bark, I run before I have time to think."

THE FOX AND THE GRAPES

A Fox saw some ripe bunches of grapes hanging high, and tried to get at them, in order to eat them.

She tried hard, but could not get them. To drown her annoyance she said:

"They are still sour."

THE MAIDS AND THE COCK

A mistress used to wake the Maids at night and, as soon as the cocks crowed, put them to work. The Maids found that hard, and decided to kill the Cock, so that the mistress should not be wakened. They killed him, but now they suffered more than ever: the mistress was afraid that she would sleep past the time and so began to wake the Maids earlier.

THE FISHERMAN AND THE FISH

A Fisherman caught a Fish. Said the Fish:

"Fisherman, let me go into the water; you see I am small: you will have little profit of me. If you let me go, I shall grow up, and then you will catch me when it will be worth while."

But the Fisherman said:

"A fool would be he who should wait for greater profit, and let the lesser slip out of his hands."

THE FOX AND THE GOAT

A Goat wanted to drink. He went down the incline to the well, drank his fill, and gained in weight. He started to get out, but could not do so. He began to bleat. A Fox saw him and said:

"That's it, stupid one! If you had as much sense in your head as there are hairs in your beard, you would have thought of how to get out before you climbed down."

THE DOG AND HER SHADOW

A Dog was crossing the river over a plank, carrying a piece of meat in her teeth. She saw herself in the water and thought that another dog was carrying a piece of meat. She dropped her piece and dashed forward to take away what the other dog had: the other meat was gone, and her own was carried away by the stream.

And thus the Dog was left without anything.

THE CRANE AND THE STORK

A peasant put out his nets to catch the Cranes for tramping down his field. In the nets were caught the Cranes, and with them one Stork.

The Stork said to the peasant:

"Let me go! I am not a Crane, but a Stork; we are most honoured birds; I live on your father's house. You can see by my feathers that I am not a Crane."

The peasant said:

"With the Cranes I have caught you, and with them will I kill you."

THE GARDENER AND HIS SONS

A Gardener wanted his Sons to get used to gardening. As he was dying, he called them up and said to them:

"Children, when I am dead, look for what is hidden in the vineyard."

The Sons thought that it was a treasure, and when their father died, they began to dig there, and dug up the whole ground. They did not find the treasure, but they ploughed the vineyard up so well that it brought forth more fruit than ever.

THE WOLF AND THE CRANE

A Wolf had a bone stuck in his throat, and could not cough it up. He called the Crane, and said to him:

"Crane, you have a long neck. Thrust your head into my throat and draw out the bone! I will reward you."

The Crane stuck his head in, pulled out the bone, and said:

"Give me my reward!"

The Wolf gnashed his teeth and said:

"Is it not enough reward for you that I did not bite off your head when it was between my teeth?"

THE HARES AND THE FROGS

The Hares once got together, and began to complain about their life:

"We perish from men, and from dogs, and from eagles, and from all the other beasts. It would be better to die at once than to live in fright and suffer. Come, let us drown ourselves!"

And the Hares raced away to drown themselves in a lake. The Frogs heard the Hares and plumped into the water. So one of the Hares said:

"Wait, boys! Let us put off the drowning! Evidently the Frogs are having a harder life than we: they are afraid even of us."

THE FATHER AND HIS SONS

A Father told his Sons to live in peace: they paid no attention to him. So he told them to bring the bath broom, and said:

"Break it!"

No matter how much they tried, they could not break it. Then the Father unclosed the broom, and told them to break the rods singly. They broke it.

The Father said:

"So it is with you: if you live in peace, no one will overcome you; but if you quarrel, and are divided, any one will easily ruin you."

THE FOX

A Fox got caught in a trap. She tore off her tail, and got away. She began to contrive how to cover up her shame. She called together the Foxes, and begged them to cut off their tails.

"A tail," she said, "is a useless thing. In vain do we drag along a dead weight."

One of the Foxes said:

"You would not be speaking thus, if you were not tailless!"

The tailless Fox grew silent and went away.

THE WILD ASS AND THE TAME ASS

A Wild Ass saw a Tame Ass. The Wild Ass went up to him and began to praise his life, saying how smooth his body was, and what sweet feed he received. Later, when the Tame Ass was loaded down, and a driver began to goad him with a stick, the Wild Ass said:

"No, brother, I do not envy you: I see that your life is going hard with you."

THE STAG

A Stag went to the brook to quench his thirst. He saw himself in the water, and began to admire his horns, seeing how large and branching they were; and he looked at his feet, and said: "But my feet are unseemly and thin."

Suddenly a Lion sprang out and made for the Stag. The Stag started to run over the open plain. He was getting away, but there came a forest, and his horns caught in the branches, and the lion caught him. As the Stag was dying, he said:

"How foolish I am! That which I thought to be unseemly and thin was saving me, and what I gloried in has been my ruin."

THE DOG AND THE WOLF

A Dog fell asleep back of the yard. A Wolf ran up and wanted to eat him.

Said the Dog:

"Wolf, don't eat me yet: now I am lean and bony. Wait a little,—my master is going to celebrate a wedding; then I shall have plenty to eat; I shall grow fat. It will be better to eat me then."

The Wolf believed her, and went away. Then he came a second time, and saw the Dog lying on the roof. The Wolf said to her:

"Well, have they had the wedding?"

The Dog replied:

"Listen, Wolf! If you catch me again asleep in front of the yard, do not wait for the wedding."

THE GNAT AND THE LION

A Gnat came to a Lion, and said:

"Do you think that you have more strength than I? You are mistaken! What does your strength consist in? Is it that you scratch with your claws, and gnaw with your teeth? That is the way the women quarrel with their husbands. I am stronger than you: if you wish let us fight!"

And the Gnat sounded his horn, and began to bite the Lion on his bare cheeks and his nose. The Lion struck his face with his paws and scratched it with his claws. He tore his face until the blood came, and gave up.

The Gnat trumpeted for joy, and flew away. Then he became entangled in a spider's web, and the spider began to suck him up. The Gnat said:

"I have vanquished the strong beast, the Lion, and now I perish from this nasty spider."

THE HORSE AND HIS MASTERS

A gardener had a Horse. She had much to do, but little to eat; so she began to pray to God to get another master. And so it happened. The gardener sold the Horse to a potter. The Horse was glad, but the potter had even more work for her to do. And again the Horse complained of her lot, and began to pray that she might get a better master. And this prayer, too, was fulfilled. The potter sold the Horse to a tanner. When the Horse saw the skins of horses in the tanner's yard, she began to cry:

"Woe to me, wretched one! It would be better if I could stay with my old masters. It is evident they have sold me now not for work, but for my skin's sake."

THE OLD MAN AND DEATH

An Old Man cut some wood, which he carried away. He had to carry it far. He grew tired, so he put down his bundle, and said:

"Oh, if Death would only come!"

Death came, and said:

"Here I am, what do you want?"

The Old Man was frightened, and said:

"Lift up my bundle!"

THE LION AND THE FOX

A Lion, growing old, was unable to catch the animals, and so intended to live by cunning. He went into a den, lay down there, and pretended that he was sick. The animals came to see him, and he ate up those that went into his den. The Fox guessed the trick. She stood at the entrance of the den, and said:

"Well, Lion, how are you feeling?"

The Lion answered:

"Poorly. Why don't you come in?"

The Fox replied:

"I do not come in because I see by the tracks that many have entered, but none have come out."

THE STAG AND THE VINEYARD

A Stag hid himself from the hunters in a vineyard. When the hunters missed him, the Stag began to nibble at the grape-vine leaves.

The hunters noticed that the leaves were moving, and so they thought, "There must be an animal under those leaves," and fired their guns, and wounded the Stag.

The Stag said, dying:

"It serves me right for wanting to eat the leaves that saved me."

THE CAT AND THE MICE

A house was overrun with Mice. A Cat found his way into the house, and began to catch them. The Mice saw that matters were bad, and said:

"Mice, let us not come down from the ceiling! The Cat cannot get up there."

When the Mice stopped coming down, the Cat decided that he must catch them by a trick. He grasped the ceiling with one leg, hung down from it, and made believe that he was dead.

A Mouse looked out at him, but said:

"No, my friend! Even if you should turn into a bag, I would not go up to you."

THE WOLF AND THE GOAT

A Wolf saw a Goat browsing on a rocky mountain, and he could not get at her; so he said to her:

"Come down lower! The place is more even, and the grass is much sweeter to feed on."

But the Goat answered:

"You are not calling me down for that, Wolf: you are troubling yourself not about my food, but about yours."

THE REEDS AND THE OLIVE-TREE

The Olive-tree and the Reeds quarrelled about who was stronger and sounder. The Olive-tree laughed at the Reeds because they bent in every wind. The Reeds kept silence. A storm came: the Reeds swayed, tossed, bowed to the ground,—and remained unharmed. The Olive-tree strained her branches against the wind,—and broke.

THE TWO COMPANIONS

Two Companions were walking through the forest when a Bear jumped out on them. One started to run, climbed a tree, and hid himself, but the other remained in the road. He had nothing to do, so he fell down on the ground and pretended that he was dead.

The Bear went up to him, and sniffed at him; but he had stopped breathing.

The Bear sniffed at his face; he thought that he was dead, and so went away.

When the Bear was gone, the Companion climbed down from the tree and laughing, said: "What did the Bear whisper in your ear?"

"He told me that those who in danger run away from their companions are bad people."

THE WOLF AND THE LAMB

A Wolf saw a Lamb drinking at a river. The Wolf wanted to eat the Lamb, and so he began to annoy him. He said:

"You are muddling my water and do not let me drink."

The Lamb said:

"How can I muddle your water? I am standing downstream from you; besides, I drink with the tips of my lips."

And the Wolf said:

"Well, why did you call my father names last summer?"

The Lamb said:

"But, Wolf, I was not yet born last summer."

The Wolf got angry, and said:

"It is hard to get the best of you. Besides, my stomach is empty, so I will devour you."

THE LION, THE WOLF, AND THE FOX

An old, sick Lion was lying in his den. All the animals came to see the king, but the Fox kept away. So the Wolf was glad of the chance, and began to slander the Fox before the Lion.

"She does not esteem you in the least," he said, "she has not come once to see the king."

The Fox happened to run by as he was saying these words. She heard what the Wolf had said, and thought:

"Wait, Wolf, I will get my revenge on you."

So the Lion began to roar at the Fox, but she said:

"Do not have me killed, but let me say a word! I did not come to see you because I had no time. And I had no time because I ran over the whole world to ask the doctors for a remedy for you. I have just got it, and so I have come to see you."

The Lion said:

"What is the remedy?"

"It is this: if you flay a live Wolf, and put his warm hide on you—"

When the Lion stretched out the Wolf, the Fox laughed, and said:

"That's it, my friend: masters ought to be led to do good, not evil."

THE LION, THE ASS, AND THE FOX

The Lion, the Ass, and the Fox went out to hunt. They caught a large number of animals, and the Lion told the Ass to divide them up. The Ass divided them into three equal parts and said: "Now, take them!"

The Lion grew angry, ate up the Ass, and told the Fox to divide them up anew. The Fox collected them all into one heap, and left a small bit for herself. The Lion looked at it and said:

"Clever Fox! Who taught you to divide so well?"

She said:

"What about that Ass?"

THE PEASANT AND THE WATER-SPRITE

A Peasant lost his axe in the river; he sat down on the bank in grief, and began to weep.

The Water-sprite heard the Peasant and took pity on him. He brought a gold axe out of the river, and said: "Is this your axe?"

The Peasant said: "No, it is not mine."

The Water-sprite brought another, a silver axe.

Again the Peasant said: "It is not my axe."

Then the Water-sprite brought out the real axe.

The Peasant said: "Now this is my axe."

The Water-sprite made the Peasant a present of all three axes, for having told the truth.

At home the Peasant showed his axes to his friends, and told them what had happened to him.

One of the peasants made up his mind to do the same: he went to the river, purposely threw his axe into the water, sat down on the bank, and began to weep.

The Water-sprite brought out a gold axe, and asked: "Is this your axe?"

The Peasant was glad, and called out: "It is mine, mine!"

The Water-sprite did not give him the gold axe, and did not bring him back his own either, because he had told an untruth.

THE RAVEN AND THE FOX

A Raven got himself a piece of meat, and sat down on a tree. The Fox wanted to get it from him. She went up to him, and said:

"Oh, Raven, as I look at you,—from your size and beauty,—you ought to be a king! And you would certainly be a king, if you had a good voice."

The Raven opened his mouth wide, and began to croak with all his might and main. The meat fell down. The Fox caught it and said:

"Oh, Raven! If you had also sense, you would certainly be a king."

II. ADAPTATIONS AND IMITATIONS OF HINDOO FABLES

THE SNAKE'S HEAD AND TAIL

The Snake's Tail had a quarrel with the Snake's Head about who was to walk in front. The Head said:

"You cannot walk in front, because you have no eyes and no ears."

The Tail said:

"Yes, but I have strength, I move you; if I want to, I can wind myself around a tree, and you cannot get off the spot."

The Head said:

"Let us separate!"

And the Tail tore himself loose from the Head, and crept on; but the moment he got away from the Head, he fell into a hole and was lost.

FINE THREAD

A Man ordered some fine thread from a Spinner. The Spinner spun it for him, but the Man said that the thread was not good, and that he wanted the finest thread he could get. The Spinner said:

"If this is not fine enough, take this!" and she pointed to an empty space.

He said that he did not see any. The Spinner said:

"You do not see it, because it is so fine. I do not see it myself."

The Fool was glad, and ordered some more thread of this kind, and paid her for what he got.

THE PARTITION OF THE INHERITANCE

A Father had two Sons. He said to them: "When I die, divide everything into two equal parts."

When the Father died, the Sons could not divide without quarrelling. They went to a Neighbour to have him settle the matter. The Neighbour asked them how their Father had told them to divide. They said:

"He ordered us to divide everything into two equal parts."

The Neighbour said:

"If so, tear all your garments into two halves, break your dishes into two halves, and cut all your cattle into two halves!"

The Brothers obeyed their Neighbour, and lost everything.

THE MONKEY

A Man went into the woods, cut down a tree, and began to saw it. He raised the end of the tree on a stump, sat astride over it, and began to saw. Then he drove a wedge into the split that he had sawed, and went on sawing; then he took out the wedge and drove it in farther down.

A Monkey was sitting on a tree and watching him. When the Man lay down to sleep, the Monkey seated herself astride the tree, and wanted to do the same; but when she took out the wedge, the tree sprang back and caught her tail. She began to tug and to cry. The Man woke up, beat the Monkey, and tied a rope to her.

THE MONKEY AND THE PEASE

A Monkey was carrying both her hands full of pease. A pea dropped on the ground; the Monkey wanted to pick it up, and dropped twenty peas. She rushed to pick them up and lost all the rest. Then she flew into a rage, swept away all the pease and ran off.

THE MILCH COW

A Man had a Cow; she gave each day a pot full of milk. The Man invited a number of guests. To have as much milk as possible, he did not milk the Cow for ten days. He thought that on the tenth day the Cow would give him ten pitchers of milk.

But the Cow's milk went back, and she gave less milk than before.

THE DUCK AND THE MOON

A Duck was swimming in the pond, trying to find some fish, but she did not find one in a whole day. When night came, she saw the Moon in the water; she thought that it was a fish, and plunged in to catch the Moon. The other ducks saw her do it and laughed at her.

That made the Duck feel so ashamed and bashful that when she saw a fish under the Water, she did not try to catch it, and so died of hunger.

THE WOLF IN THE DUST

A Wolf wanted to pick a sheep out of a flock, and stepped into the wind, so that the dust of the flock might blow on him.

The Sheep Dog saw him, and said:

"There is no sense, Wolf, in your walking in the dust: it will make your eyes ache."

But the Wolf said:

"The trouble is, Doggy, that my eyes have been aching for quite awhile, and I have been told that the dust from a flock of sheep will cure the eyes."

THE MOUSE UNDER THE GRANARY

A Mouse was living under the granary. In the floor of the granary there was a little hole, and the grain fell down through it. The Mouse had an easy life of it, but she wanted to brag of her ease: she gnawed a larger hole in the floor, and invited other mice.

"Come to a feast with me," said she; "there will be plenty to eat for everybody."

When she brought the mice, she saw there was no hole. The peasant had noticed the big hole in the floor, and had stopped it up.

THE BEST PEARS

A master sent his Servant to buy the best-tasting pears. The Servant came to the shop and asked for pears. The dealer gave him some; but the Servant said:

"No, give me the best!"

The dealer said:

"Try one; you will see that they taste good."

"How shall I know," said the Servant, "that they all taste good, if I try one only?"

He bit off a piece from each pear, and brought them to his master. Then his master sent him away.

THE FALCON AND THE COCK

The Falcon was used to the master, and came to his hand when he was called; the Cock ran away from his master and cried when people went up to him. So the Falcon said to the Cock:

"In you Cocks there is no gratitude; one can see that you are of a common breed. You go to your masters only when you are hungry. It is different with us wild birds. We have much strength, and we can fly faster than anybody; still we do not fly away from people, but of our own accord go to their hands when we are called. We remember that they feed us."

Then the Cock said:

"You do not run away from people because you have never seen a roast Falcon, but we, you know, see roast Cocks."

THE JACKALS AND THE ELEPHANT

The Jackals had eaten up all the carrion in the woods, and had nothing to eat. So an old Jackal was thinking how to find something to feed on. He went to an Elephant, and said:

"We had a king, but he became overweening: he told us to do things that nobody could do; we want to choose another king, and my people have sent me to ask you to be our king. You will have an easy life with us. Whatever you will order us to do, we will do, and we will honour you in everything. Come to our kingdom!"

The Elephant consented, and followed the Jackal. The Jackal brought him to a swamp. When the Elephant stuck fast in it, the Jackal said:

"Now command! Whatever you command, we will do."

The Elephant said:

"I command you to pull me out from here."

The Jackal began to laugh, and said:

"Take hold of my tail with your trunk, and I will pull you out at once."

The Elephant said:

"Can I be pulled out by a tail?"

But the Jackal said to him:

"Why, then, do you command us to do what is impossible? Did we not drive away our first king for telling us to do what could not be done?"

When the Elephant died in the swamp the Jackals came and ate him up.

THE HERON, THE FISHES, AND THE CRAB

A Heron was living near a pond. She grew old, and had no strength left with which to catch the fish. She began to contrive how to live by cunning. So she said to the Fishes:

"You Fishes do not know that a calamity is in store for you: I have heard the people say that they are going to let off the pond, and catch every one of you. I know of a nice little pond back of the mountain. I should like to help you, but I am old, and it is hard for me to fly."

The Fishes begged the Heron to help them. So the Heron said:

"All right, I will do what I can for you, and will carry you over: only I cannot do it at once,—I will take you there one after another."

And the Fishes were happy; they kept begging her: "Carry me over! Carry me over!"

And the Heron started carrying them. She would take one up, would carry her into the field, and would eat her up. And thus she ate a large number of Fishes.

In the pond there lived an old Crab. When the Heron began to take out the Fishes, he saw what was up, and said:

"Now, Heron, take me to the new abode!"

The Heron took the Crab and carried him off. When she flew out on the field, she wanted to throw the Crab down. But the Crab saw the fish-bones on the ground, and so squeezed the Heron's neck with his claws, and choked her to death. Then he crawled back to the pond, and told the Fishes.

THE WATER-SPRITE AND THE PEARL

A Man was rowing in a boat, and dropped a costly pearl into the sea. The Man returned to the shore, took a pail, and began to draw up the water and to pour it out on the land. He drew the water and poured it out for three days without stopping.

On the fourth day the Water-sprite came out of the sea, and asked:

"Why are you drawing the water?"

The Man said:

"I am drawing it because I have dropped a pearl into it."

The Water-sprite asked him:

"Will you stop soon?"

The Man said:

"I will stop when I dry up the sea."

Then the Water-sprite returned to the sea, brought back that pearl, and gave it to the Man.

THE BLIND MAN AND THE MILK

A Man born blind asked a Seeing Man:

"Of what colour is milk?"

The Seeing Man said: "The colour of milk is the same as that of white paper."

The Blind Man asked: "Well, does that colour rustle in your hands like paper?"

The Seeing Man said: "No, it is as white as white flour."

The Blind Man asked: "Well, is it as soft and as powdery as flour?"

The Seeing Man said: "No, it is simply as white as a white hare."

The Blind Man asked: "Well, is it as fluffy and soft as a hare?"

The Seeing Man said: "No, it is as white as snow."

The Blind Man asked: "Well, is it as cold as snow?"

And no matter how many examples the Seeing Man gave, the Blind Man was unable to understand what the white colour of milk was like.

THE WOLF AND THE BOW

A hunter went out to hunt with bow and arrows. He killed a goat. He threw her on his shoulders and carried her along. On his way he saw a boar. He threw down the goat, and shot at the boar and wounded him. The boar rushed against the hunter and butted him to death, and himself died on the spot. A Wolf scented the blood, and came to the place where lay the goat, the boar, the man, and his bow. The Wolf was glad, and said:

"Now I shall have enough to eat for a long time; only I will not eat everything at once, but little by little, so that nothing may be lost: first I will eat the tougher things, and then I will lunch on what is soft and sweet."

The Wolf sniffed at the goat, the boar, and the man, and said:

"This is all soft food, so I will eat it later; let me first start on these sinews of the bow."

And he began to gnaw the sinews of the bow. When he bit through the string, the bow sprang back and hit him on his belly. He died on the spot, and other wolves ate up the man, the goat, the boar, and the Wolf.

THE BIRDS IN THE NET

A Hunter set out a net near a lake and caught a number of birds. The birds were large, and they raised the net and flew away with it. The Hunter ran after them. A Peasant saw the Hunter running, and said:

"Where are you running? How can you catch up with the birds, while you are on foot?"

The Hunter said:

"If it were one bird, I should not catch it, but now I shall."

And so it happened. When evening came, the birds began to pull for the night each in a different direction: one to the woods, another to the swamp, a third to the field; and all fell with the net to the ground, and the Hunter caught them.

THE KING AND THE FALCON

A certain King let his favourite Falcon loose on a hare, and galloped after him.

The Falcon caught the hare. The King took him away, and began to look for some water to drink. The King found it on a knoll, but it came only drop by drop. The King fetched his cup from the saddle, and placed it under the water. The Water flowed in drops, and when the cup was filled, the King raised it to his mouth and wanted to drink it. Suddenly the Falcon fluttered on the King's arm and spilled the water. The King placed the cup once more under the drops. He waited for a long time for the cup to be filled even with the brim, and again, as he carried it to his mouth, the Falcon flapped his wings and spilled the water.

When the King filled his cup for the third time and began to carry it to his mouth, the Falcon again spilled it. The King flew into a rage and killed him by flinging him against a stone with all his force. Just then the King's servants rode up, and one of them ran up-hill to the spring, to find as much water as possible, and to fill the cup. But the servant did not bring the water; he returned with the empty cup, and said:

"You cannot drink that water; there is a snake in the spring, and she has let her venom into the water. It is fortunate that the Falcon has spilled the water. If you had drunk it, you would have died."

The King said:

"How badly I have repaid the Falcon! He has saved my life, and I killed him."

THE KING AND THE ELEPHANTS

An Indian King ordered all the Blind People to be assembled, and when they came, he ordered that all the Elephants be shown to them. The Blind Men went to the stable and began to feel the Elephants. One felt a leg, another a tail, a third the stump of a tail, a fourth a belly, a fifth a back, a sixth the ears, a seventh the tusks, and an eighth a trunk.

Then the King called the Blind Men, and asked them: "What are my Elephants like?"

One Blind Man said: "Your Elephants are like posts." He had felt the legs.

Another Blind Man said: "They are like bath brooms." He had felt the end of the tail.

A third said: "They are like branches." He had felt the tail stump.

The one who had touched a belly said: "The Elephants are like a clod of earth."

The one who had touched the sides said: "They are like a wall."

The one who had touched a back said: "They are like a mound."

The one who had touched the ears said: "They are like a mortar."

The one who had touched the tusks said: "They are like horns."

The one who had touched the trunk said that they were like a stout rope.

And all the Blind Men began to dispute and to quarrel.

WHY THERE IS EVIL IN THE WORLD

A Hermit was living in the forest, and the animals were not afraid of him. He and the animals talked together and understood each other.

Once the Hermit lay down under a tree, and a Raven a Dove, a Stag, and a Snake gathered in the same place, to pass the night. The animals began to discuss why there was evil in the world.

The Raven said:

"All the evil in the world comes from hunger. When I eat my fill, I sit down on a branch and croak a little, and it is all jolly and good, and everything gives me pleasure; but let me just go without eating a day or two, and everything palls on me so that I do not feel like looking at God's world. And something draws me on, and I fly from place to place, and have no rest. When I catch a glimpse of some meat, it makes me only feel sicker than ever, and I make for it without much thinking. At times they throw sticks and stones at me, and the wolves and dogs grab me, but I do not give in. Oh, how many of my brothers are perishing through hunger! All evil comes from hunger."

The Dove said:

"According to my opinion, the evil does not come from hunger, but from love. If we lived singly, the trouble would not be so bad. One head is not poor, and if it is, it is only one. But here we live in pairs. And you come to like your mate so much that you have no rest: you keep thinking of her all the time, wondering whether she has had enough to eat, and whether she is warm. And when your mate flies away from you, you feel entirely lost, and you keep thinking that a hawk may have carried her off, or men may have caught her; and you start out to find her, and fly to your ruin,—either into the hawk's claws, or into a snare. And when your mate is lost, nothing gives you any joy. You do not eat or drink, and all the time search and weep. Oh, so many of us perish in this way! All the evil is not from hunger, but from love."

The Snake said:

"No, the evil is not from hunger, nor from love, but from rage. If we lived peacefully, without getting into a rage, everything would be nice for us. But, as it is, whenever a thing does not go exactly right, we get angry, and then nothing pleases us. All we think about is how to revenge ourselves on some one. Then we forget ourselves, and only hiss, and creep, and try to find some one to bite. And we do not spare a soul,—we even bite our own father and mother. We feel as though we could eat ourselves up. And we rage until we perish. All the evil in the World comes from rage."

The Stag said:

"No, not from rage, or from love, or from hunger does all the evil in the world come, but from terror. If it were possible not to be afraid, everything would be well. We have swift feet and much strength: against a small animal we defend ourselves with our horns, and from a large one we flee. But how can I help becoming frightened? Let a branch crackle in the forest, or a leaf rustle, and I am all atremble with fear, and my heart flutters as though it wanted to jump out, and I fly as fast as I can. Again, let a hare run by, or a bird flap its wings, or a dry twig break off, and you think that it is a beast, and you run straight up against him. Or you run away from a dog and run into the hands of a man. Frequently you get frightened and run, not knowing whither, and at full speed rush down a steep hill, and get killed. We have no rest. All the evil comes from terror."

Then the Hermit said:

"Not from hunger, not from love, not from rage, not from terror are all our sufferings, but from our bodies comes all the evil in the world. From them come hunger, and love, and rage, and terror."

THE WOLF AND THE HUNTERS

A Wolf devoured a sheep. The Hunters caught the Wolf and began to beat him. The Wolf said:

"In vain do you beat me: it is not my fault that I am gray,—God has made me so."

But the Hunters said:

"We do not beat the Wolf for being gray, but for eating the sheep."

THE TWO PEASANTS

Once upon a time two Peasants drove toward each other and caught in each other's sleighs. One cried:

"Get out of my way,—I am hurrying to town."

But the other said:

"Get out of my way, I am hurrying home."

They quarrelled for some time. A third Peasant saw them and said:

"If you are in a hurry, back up!"

THE PEASANT AND THE HORSE

A Peasant went to town to fetch some oats for his Horse. He had barely left the village, when the Horse began to turn around, toward the house. The Peasant struck the Horse with his whip. She went on, and kept thinking about the Peasant:

"Whither is that fool driving me? He had better go home."

Before reaching town, the Peasant saw that the Horse trudged along through the mud with difficulty, so he turned her on the pavement; but the Horse began to turn back from the street. The Peasant gave the Horse the whip, and jerked at the reins; she went on the pavement, and thought:

"Why has he turned me on the pavement? It will only break my hoofs. It is rough underfoot."

The Peasant went to the shop, bought the oats, and drove home. When he came home, he gave the Horse some oats. The Horse ate them and thought:

"How stupid men are! They are fond of exercising their wits on us, but they have less sense than we. What did he trouble himself about? He drove me somewhere. No matter how far we went, we came home in the end. So it would have been better if we had remained at home from the start: he could have been sitting on the oven, and I eating oats."

THE TWO HORSES

Two Horses were drawing their carts. The Front Horse pulled well, but the Hind Horse kept stopping all the time. The load of the Hind Horse was transferred to the front cart; when all was transferred, the Hind Horse went along with ease, and said to the Front Horse:

"Work hard and sweat! The more you try, the harder they will make you work."

When they arrived at the tavern, their master said:

"Why should I feed two Horses, and haul with one only? I shall do better to give one plenty to eat, and to kill the other: I shall at least have her hide."

So he did.

THE AXE AND THE SAW

Two Peasants went to the forest to cut wood. One of them had an axe, and the other a saw. They picked out a tree, and began to dispute. One said that the tree had to be chopped, while the other said that it had to be sawed down.

A third Peasant said:

"I will easily make peace between you: if the axe is sharp, you had better chop it; but if the saw is sharp you had better saw it."

He took the axe, and began to chop it; but the axe was so dull that it was not possible to cut with it. Then he took the saw; the saw was worthless, and did not saw. So he said:

"Stop quarrelling awhile; the axe does not chop, and the saw does not saw. First grind your axe and file your saw, and then quarrel."

But the Peasants grew angrier still at one another, because one had a dull axe, and the other a dull saw. And they came to blows.

THE DOGS AND THE COOK

A Cook was preparing a dinner. The Dogs were lying at the kitchen door. The Cook killed a calf and threw the guts out into the yard. The Dogs picked them up and ate them, and said:

"He is a good Cook: he cooks well."

After awhile the Cook began to clean pease, turnips, and onions, and threw out the refuse. The Dogs made for it; but they turned their noses up, and said:

"Our Cook has grown worse: he used to cook well, but now he is no longer any good."

But the Cook paid no attention to the Dogs, and continued to fix the dinner in his own way. The family, and not the Dogs, ate the dinner, and praised it.

THE HARE AND THE HARRIER

A Hare once said to a Harrier:

"Why do you bark when you run after us? You would catch us easier, if you ran after us in silence. With your bark you only drive us against the hunter: he hears where we are running; and he rushes out with his gun and kills us, and does not give you anything."

The Harrier said:

"That is not the reason why I bark. I bark because, when I scent your odour, I am angry, and happy because I am about to catch you; I do not know why, but I cannot keep from barking."

THE OAK AND THE HAZELBUSH

An old Oak dropped an acorn under a Hazelbush. The Hazelbush said to the Oak:

"Have you not enough space under your own branches? Drop your acorns in an open space. Here I am myself crowded by my shoots, and I do not drop my nuts to the ground, but give them to men."

"I have lived for two hundred years," said the Oak, "and the Oakling which will sprout from that acorn will live just as long."

Then the Hazelbush flew into a rage, and said:

"If so, I will choke your Oakling, and he will not live for three days."

The Oak made no reply, but told his son to sprout out of that acorn. The acorn got wet and burst, and clung to the ground with his crooked rootlet, and sent up a sprout.

The Hazelbush tried to choke him, and gave him no sun. But the Oakling spread upwards and grew stronger in the shade of the Hazelbush. A hundred years passed. The Hazelbush had long ago dried up, but the Oak from that acorn towered to the sky and spread his tent in all directions.

THE HEN AND THE CHICKS

A Hen hatched some Chicks, but did not know how to take care of them. So she said to them:

"Creep back into your shells! When you are inside your shells, I will sit on you as before, and will take care of you."

The Chicks did as they were ordered and tried to creep into their shells, but were unable to do so, and only crushed their wings. Then one of the Chicks said to his mother:

"If we are to stay all the time in our shells, you ought never to have hatched us."

THE CORN-CRAKE AND HIS MATE

A Corn-crake had made a nest in the meadow late in the year, and at mowing time his Mate was still sitting on her eggs. Early in the morning the peasants came to the meadow, took off the coats, whetted their scythes, and started one after another to mow down the grass and to put it down in rows. The Corn-crake flew up to see what the mowers were doing. When he saw a peasant swing his scythe and cut a snake in two, he rejoiced and flew back to his Mate and said:

"Don't fear the peasants! They have come to cut the snakes to pieces; they have given us no rest for quite awhile."

But his Mate said:

"The peasants are cutting the grass, and with the grass they are cutting everything which is in their way,—the snakes, and the Corn-crake's nest, and the Corn-crake's head. My heart forebodes nothing good: but I cannot carry away the eggs, nor fly from the nest, for fear of chilling them."

When the mowers came to the nest of the Corn-crake, one of the peasants swung his scythe and cut off the head of the Corn-crake's Mate, and put the eggs in his bosom and gave them to his children to play with.

THE COW AND THE BILLY GOAT

An old woman had a Cow and a Billy Goat. The two pastured together. At milking the Cow was restless. The old woman brought out some bread and salt, and gave it to the Cow, and said:

"Stand still, motherkin; take it, take it! I will bring you some more, only stand still."

On the next evening the Goat came home from the field before the Cow, and spread his legs, and stood in front of the old woman. The old woman wanted to strike him with the towel, but he stood still, and did not stir. He remembered that the woman had promised the Cow some bread if she would stand still. When the woman saw that he would not budge, she picked up a stick, and beat him with it.

When the Goat went away, the woman began once more to feed the Cow with bread, and to talk to her.

"There is no honesty in men," thought the Goat. "I stood still better than the Cow, and was beaten for it."

He stepped aside, took a run, hit against the milk-pail, spilled the milk, and hurt the old woman.

THE FOX'S TAIL

A Man caught a Fox, and asked her:

"Who has taught you Foxes to cheat the dogs with your tails?"

The Fox asked: "How do you mean, to cheat? We do not cheat the dogs, but simply run from them as fast as we can."

The Man said:

"Yes, you do cheat them with your tails. When the dogs catch up with you and are about to clutch you, you turn your tails to one side; the dogs turn sharply after the tail, and then you run in the opposite direction."

The Fox laughed, and said:

"We do not do so in order to cheat the dogs, but in order to turn around; when a dog is after us, and we see that we cannot get away straight ahead, we turn to one side, and in order to do that suddenly, we have to swing the tail to the other side, just as you do with your arms, when you have to turn around. That is not our invention; God himself invented it when He created us, so that the dogs might not be able to catch all the Foxes."

STORIES FOR CHILDREN

1869-1872

STORIES FOR CHILDREN

THE FOUNDLING

A poor woman had a daughter by the name of Másha. Másha went in the morning to fetch water, and saw at the door something wrapped in rags. When she touched the rags, there came from it the sound of "Ooah, ooah, ooah!" Másha bent down and saw that it was a tiny, red-skinned baby. It was crying aloud: "Ooah, ooah!"

Másha took it into her arms and carried it into the house, and gave it milk with a spoon. Her mother said:

"What have you brought?"

"A baby. I found it at our door."

The mother said:

"We are poor as it is; we have nothing to feed the baby with; I will go to the chief and tell him to take the baby."

Másha began to cry, and said:

"Mother, the child will not eat much; leave it here! See what red, wrinkled little hands and fingers it has!"

Her mother looked at them, and she felt pity for the child. She did not take the baby away. Másha fed and swathed the child, and sang songs to it, when it went to sleep.

THE PEASANT AND THE CUCUMBERS

A peasant once went to the gardener's, to steal cucumbers. He crept up to the cucumbers, and thought:

"I will carry off a bag of cucumbers, which I will sell; with the money I will buy a hen. The hen will lay eggs, hatch them, and raise a lot of chicks. I will feed the chicks and sell them; then I will buy me a young sow, and she will bear a lot of pigs. I will sell the pigs, and buy me a mare; the mare will foal me some colts. I will raise the colts, and sell them. I will buy me a house, and start a garden. In the garden I will sow cucumbers, and will not let them be stolen, but will keep a sharp watch on them. I will hire watchmen, and put them in the cucumber patch, while I myself will come on them, unawares, and shout: 'Oh, there, keep a sharp lookout!'"

And this he shouted as loud as he could. The watchmen heard it, and they rushed out and beat the peasant.

THE FIRE

During harvest-time the men and women went out to work. In the village were left only the old and the very young. In one hut there remained a grandmother with her three grandchildren.

The grandmother made a fire in the oven, and lay down to rest herself. Flies kept alighting on her and biting her. She covered her head with a towel and fell asleep. One of the grandchildren, Másha (she was three years old), opened the oven, scraped some coals into a potsherd, and went into the vestibule. In the vestibule lay sheaves: the women were getting them bound.

Másha brought the coals, put them under the sheaves, and began to blow. When the straw caught fire, she was glad; she went into the hut and took her brother Kiryúsha by the arm (he was a year and a half old, and had just learned to walk), and brought him out, and said to him:

"See, Kiryúsha, what a fire I have kindled."

The sheaves were already burning and crackling. When the vestibule was filled with smoke, Másha became frightened and ran back into the house. Kiryúsha fell over the threshold, hurt his nose, and began to cry; Másha pulled him into the house, and both hid under a bench.

The grandmother heard nothing, and did not wake. The elder boy, Ványa (he was eight years old), was in the street. When he saw the smoke rolling out of the vestibule, he ran to the door, made his way through the smoke into the house, and began to waken his grandmother; but she was dazed from her sleep, and, forgetting the children, rushed out and ran to the farmyards to call the people.

In the meantime Másha was sitting under the bench and keeping quiet; but the little boy cried, because he had hurt his nose badly. Ványa heard his cry, looked under the bench, and called out to Másha:

"Run, you will burn!"

Másha ran to the vestibule, but could not pass for the smoke and fire. She turned back. Then Ványa raised a window and told her to climb through it. When she got through, Ványa picked up his brother and dragged him along. But the child was heavy and did not let his brother take him. He cried and pushed Ványa. Ványa fell down twice, and when he dragged him up to the window, the door of the hut was already burning. Ványa thrust the child's head through the window and wanted to push him through; but the child took hold of him with both his hands (he was very much frightened) and would not let them take him out. Then Ványa cried to Másha:

"Pull him by the head!" while he himself pushed him behind.

And thus they pulled him through the window and into the street.

THE OLD HORSE

In our village there was an old, old man, Pímen Timoféich. He was ninety years old. He was living at the house of his grandson, doing no work. His back was bent: he walked with a cane and moved his feet slowly.

He had no teeth at all, and his face was wrinkled. His nether lip trembled; when he walked and when he talked, his lips smacked, and one could not understand what he was saying.

We were four brothers, and we were fond of riding. But we had no gentle riding-horses. We were allowed to ride only on one horse,—the name of that horse was Raven.

One day mamma allowed us to ride, and all of us went with the valet to the stable. The coachman saddled Raven for us, and my eldest brother was the first to take a ride. He rode for a long time; he rode to the threshing-floor and around the garden, and when he came back, we shouted:

"Now gallop past us!"

My elder brother began to strike Raven with his feet and with the whip, and Raven galloped past us.

After him, my second brother mounted the horse. He, too, rode for quite awhile, and he, too, urged Raven on with the whip and galloped up the hill. He wanted to ride longer, but my third brother begged him to let him ride at once.

My third brother rode to the threshing-floor, and around the garden, and down the village, and raced up-hill to the stable. When he rode up to us Raven was panting, and his neck and shoulders were dark from sweat.

When my turn came, I wanted to surprise my brothers and to show them how well I could ride, so I began to drive Raven with all my might, but he did not want to get away from the stable. And no matter how much I beat him, he would not run, but only shied and turned back. I grew angry at the horse, and struck him as hard as I could with my feet and with the whip. I tried to strike him in places where it would hurt most; I broke the whip and began to strike his head with what was left of the whip. But Raven would not run. Then I turned back, rode up to the valet, and asked him for a stout switch. But the valet said to me:

"Don't ride any more, sir! Get down! What use is there in torturing the horse?"

I felt offended, and said:

"But I have not had a ride yet. Just watch me gallop! Please, give me a good-sized switch! I will heat him up."

Then the valet shook his head, and said:

"Oh, sir, you have no pity; why should you heat him up? He is twenty years old. The horse is worn out; he can barely breathe, and is old. He is so very old! Just like Pímen Timoféich. You might just as well sit down on Timoféich's back and urge him on with a switch. Well, would you not pity him?"

I thought of Pímen, and listened to the valet's words. I climbed down from the horse and, when I saw how his sweaty sides hung down, how he breathed heavily through his nostrils, and how he switched his bald tail, I understood that it was hard for the horse. Before that I used to think that it was as much fun for him as for me. I felt so sorry for Raven that I began to kiss his sweaty neck and to beg his forgiveness for having beaten him.

Since then I have grown to be a big man, and I always am careful with the horses, and always think of Raven and of Pímen Timoféitch whenever I see anybody torture a horse.

HOW I LEARNED TO RIDE

When I was a little fellow, we used to study every day, and only on Sundays and holidays went out and played with our brothers. Once my father said:

"The children must learn to ride. Send them to the riding-school!"

I was the youngest of the brothers, and I asked:

"May I, too, learn to ride?"

My father said:

"You will fall down."

I began to beg him to let me learn, and almost cried. My father said:

"All right, you may go, too. Only look out! Don't cry when you fall off. He who does not once fall down from a horse will not learn to ride."

When Wednesday came, all three of us were taken to the riding-school. We entered by a large porch, and from the large porch went to a smaller one. Beyond the porch was a very large room: instead of a floor it had sand. And in this room were gentlemen and ladies and just such boys as we. That was the riding-school. The riding-school was not very light, and there was a smell of horses, and you could hear them snap whips and call to the horses, and the horses strike their hoofs against the wooden walls. At first I was frightened and could not see things well. Then our valet called the riding-master, and said:

"Give these boys some horses: they are going to learn how to ride."

The master said:

"All right!"

Then he looked at me, and said:

"He is very small, yet."

But the valet said:

"He promised not to cry when he falls down."

The master laughed and went away.

Then they brought three saddled horses, and we took off our cloaks and walked down a staircase to the riding-school. The master was holding a horse by a cord, and my brothers rode around him. At first they rode at a slow pace, and later at a trot. Then they brought a pony. It was a red horse, and his tail was cut off. He was called Ruddy. The master laughed, and said to me:

"Well, young gentleman, get on your horse!"

I was both happy and afraid, and tried to act in such a manner as not to be noticed by anybody. For a long time I tried to get my foot into the stirrup, but could not do it because I was too small. Then the master raised me up in his hands and put me on the saddle. He said:

"The young master is not heavy,—about two pounds in weight, that is all."

At first he held me by my hand, but I saw that my brothers were not held, and so I begged him to let go of me. He said:

"Are you not afraid?"

I was very much afraid, but I said that I was not. I was so much afraid because Ruddy kept dropping his ears. I thought he was angry at me. The master said:

"Look out, don't fall down!" and let go of me. At first Ruddy went at a slow pace, and I sat up straight. But the saddle was sleek, and I was afraid I would slip off. The master asked me:

"Well, are you fast in the saddle?"

I said:

"Yes, I am."

"If so, go at a slow trot!" and the master clicked his tongue.

Ruddy started at a slow trot, and began to jog me. But I kept silent, and tried not to slip to one side. The master praised me:

"Oh, a fine young gentleman, indeed!"

I was very glad to hear it.

Just then the master's friend went up to him and began to talk with him, and the master stopped looking at me.

Suddenly I felt that I had slipped a little to one side on my saddle. I wanted to straighten myself up, but was unable to do so. I wanted to call out to the master to stop the horse, but I thought it would be a disgrace if I did it, and so kept silence. The master was not looking at me and Ruddy ran at a trot, and I slipped still more to one side. I looked at the master and thought that he would help me, but he was still talking with his friend, and without looking at me kept repeating:

"Well done, young gentleman!"

I was now altogether to one side, and was very much frightened. I thought that I was lost; but I felt ashamed to cry. Ruddy shook me up once more, and I slipped off entirely and fell to the ground. Then Ruddy stopped, and the master looked at the horse and saw that I was not on him. He said:

"I declare, my young gentleman has dropped off!" and walked over to me.

When I told him that I was not hurt, he laughed and said:

"A child's body is soft."

I felt like crying. I asked him to put me again on the horse, and I was lifted on the horse. After that I did not fall down again.

Thus we rode twice a week in the riding-school, and I soon learned to ride well, and was not afraid of anything.

THE WILLOW

During Easter week a peasant went out to see whether the ground was all thawed out.

He went into the garden and touched the soil with a stick. The earth was soft. The peasant went into the woods; here the catkins were already swelling on the willows. The peasant thought:

"I will fence my garden with willows; they will grow up and will make a good hedge!"

He took his axe, cut down a dozen willows, sharpened them at the end, and stuck them in the ground.

All the willows sent up sprouts with leaves, and underground let out just such sprouts for roots; and some of them took hold of the ground and grew, and others did not hold well to the ground with their roots, and died and fell down.

In the fall the peasant was glad at the sight of his willows: six of them had taken root. The following spring the sheep killed two willows by gnawing at them, and only two were left. Next spring the sheep nibbled at these also. One of them was completely ruined, and the other came to, took root, and grew to be a tree. In the spring the bees just buzzed in the willow. In swarming time the swarms were often put out on the willow, and the peasants brushed them in. The men and women frequently ate and slept under the willow, and the children climbed on it and broke off rods from it.

The peasant that had set out the willow was long dead, and still it grew. His eldest son twice cut down its branches and used them for fire-wood. The willow kept growing. They trimmed it all around, and cut it down to a stump, but in the spring it again sent out twigs, thinner ones than before, but twice as many as ever, as is the case with a colt's forelock.

And the eldest son quit farming, and the village was given up, but the willow grew in the open field. Other peasants came there, and chopped the willow, but still it grew. The lightning struck it; but it sent forth side branches, and it grew and blossomed. A peasant wanted to cut it down for a block, but he gave it up, it was too rotten. It leaned sidewise, and held on with one side only; and still it grew, and every year the bees came there to gather the pollen.

One day, early in the spring, the boys gathered under the willow, to watch the horses. They felt cold, so they started a fire. They gathered stubbles, wormwood, and sticks. One of them climbed on the willow and broke off a lot of twigs. They put it all in the hollow of the willow and set fire to it. The tree began to hiss and its sap to boil, and the smoke rose and the tree burned; its whole inside was smudged. The young shoots dried up, the blossoms withered.

The children drove the horses home. The scorched willow was left all alone in the field. A black raven flew by, and he sat down on it, and cried:

"So you are dead, old smudge! You ought to have died long ago!"

BÚLKA

I had a small bulldog. He was called Búlka. He was black; only the tips of his front feet were white. All bulldogs have their lower jaws longer than the upper, and the upper teeth come down behind the nether teeth, but Búlka's lower jaw protruded so much that I could put my finger between the two rows of teeth. His face was broad, his eyes large, black, and sparkling; and his teeth and incisors stood out prominently. He was as black as a negro. He was gentle and did not bite, but he was strong and stubborn. If he took hold of a thing, he clenched his teeth and clung to it like a rag, and it was not possible to tear him off, any more than as though he were a lobster.

Once he was let loose on a bear, and he got hold of the bear's ear and stuck to him like a leech. The bear struck him with his paws and squeezed him, and shook him from side to side, but could not tear himself loose from him, and so he fell down on his head, in order to crush Búlka; but Búlka held on to him until they poured cold water over him.

I got him as a puppy, and raised him myself. When I went to the Caucasus, I did not want to take him along, and so went away from him quietly, ordering him to be shut up. At the first station I was about to change the relay, when suddenly I saw something black and shining coming down the road. It was Búlka in his brass collar. He was flying at full speed toward the station. He rushed up to me, licked my hand, and stretched himself out in the shade under the cart. His tongue stuck out a whole hand's length. He now drew it in to swallow the spittle, and now stuck it out again a whole hand's length. He tried to breathe fast, but could not do so, and his sides just shook. He turned from one side to the other, and struck his tail against the ground.

I learned later that after I had left he had broken a pane, jumped out of the window, and followed my track along the road, and thus raced twenty versts through the greatest heat.

BÚLKA AND THE WILD BOAR

Once we went into the Caucasus to hunt the wild boar, and Búlka went with me. The moment the hounds started, Búlka rushed after them, following their sound, and disappeared in the forest. That was in the month of November; the boars and sows are then very fat.

In the Caucasus there are many edible fruits in the forests where the boars live: wild grapes, cones, apples, pears, blackberries, acorns, wild plums. And when all these fruits get ripe and are touched by the frost, the boars eat them and grow fat.

At that time a boar gets so fat that he cannot run from the dogs. When they chase him for about two hours, he makes for the thicket and there stops. Then the hunters run up to the place where he stands, and shoot him. They can tell by the bark of the hounds whether the boar has stopped, or is running. If he is running, the hounds yelp, as though they were beaten; but when he stops, they bark as though at a man, with a howling sound.

During that chase I ran for a long time through the forest, but not once did I cross a boar track. Finally I heard the long-drawn bark and howl of the hounds, and ran up to that place. I was already near the boar. I could hear the crashing in the thicket. The boar was turning around on the dogs, but I could not tell by the bark that they were not catching him, but only circling around him. Suddenly I heard something rustle behind me, and I saw that it was Búlka. He had evidently strayed from the hounds in the forest and had lost his way, and now was hearing their barking and making for them, like me, as fast as he could. He ran across a clearing through the high grass, and all I could see of him was his black head and his tongue clinched between his white teeth. I called him back, but he did not look around, and ran past me and disappeared in the thicket. I ran after him, but the farther I went, the more and more dense did the forest grow. The branches kept knocking off my cap and struck me in the face, and the thorns caught in my garments. I was near to the barking, but could not see anything.

Suddenly I heard the dogs bark louder, and something crashed loudly, and the boar began to puff and snort. I immediately made up my mind that Búlka had got up to him and was busy with him. I ran with all my might through the thicket to that place. In the densest part of the thicket I saw a dappled hound. She was barking and howling in one spot, and within three steps from her something black could be seen moving around.

When I came nearer, I could make out the boar, and I heard Búlka whining shrilly. The boar grunted and made for the hound; the hound took her tail between her legs and leaped away. I could see the boar's side and head. I aimed at his side and fired. I saw that I had hit him. The boar grunted and crashed through the thicket away from me. The dogs whimpered and barked in his track; I tried to follow them through the undergrowth. Suddenly I saw and heard something almost under my feet. It was Búlka. He was lying on his side and whining. Under him there was a puddle of blood. I thought the dog was lost; but I had no time to look after him, I continued to make my way through the thicket. Soon I saw the boar. The dogs were trying to catch him from behind, and he kept turning, now to one side, and now to another. When the boar saw me, he moved toward me. I fired a second time, almost resting the barrel against him, so that his bristles caught fire, and the boar groaned and tottered, and with his whole cadaver dropped heavily on the ground.

When I came up, the boar was dead, and only here and there did his body jerk and twitch. Some of the dogs, with bristling hair, were tearing his belly and legs, while the others were lapping the blood from his wound.

Then I thought of Búlka, and went back to find him. He was crawling toward me and groaning. I went up to him and looked at his wound. His belly was ripped open, and a whole piece of his guts was sticking out of his body and dragging on the dry leaves. When my companions came up to me, we put the guts back and sewed up his belly. While we were sewing him up and sticking the needle through his skin, he kept licking my hand.

The boar was tied up to the horse's tail, to pull him out of the forest, and Búlka was put on the horse, and thus taken home. Búlka was sick for about six weeks, and got well again.

PHEASANTS

Wild fowls are called pheasants in the Caucasus. There are so many of them that they are cheaper there than tame chickens. Pheasants are hunted with the "hobby," by scaring up, and from under dogs. This is the way they are hunted with the "hobby." They take a piece of canvas and stretch it over a frame, and in the middle of the frame they make a cross piece. They cut a hole in the canvas. This frame with the canvas is called a hobby. With this hobby and with the gun they start out at dawn to the forest. The hobby is carried in front, and through the hole they look out for the pheasants. The pheasants feed at daybreak in the clearings. At times it is a whole brood,—a hen with all her chicks, and at others a cock with his hen, or several cocks together.

The pheasants do not see the man, and they are not afraid of the canvas and let the hunter come close to them. Then the hunter puts down the hobby, sticks his gun through the rent, and shoots at whichever bird he pleases.

This is the way they hunt by scaring up. They let a watch-dog into the forest and follow him. When the dog finds a pheasant, he rushes for it. The pheasant flies on a tree, and then the dog begins to bark at it. The hunter follows up the barking and shoots the pheasant in the tree. This chase would be easy, if the pheasant alighted on a tree in an open place, or if it sat still, so that it might be seen. But they always alight on dense trees, in the thicket, and when they see the hunter they hide themselves in the branches. And it is hard to make one's way through the thicket to the tree on which a pheasant is sitting, and hard to see it. So long as the dog alone barks at it, it is not afraid: it sits on a branch and preens and flaps its wings at the dog. But the moment it sees a man, it immediately stretches itself out along a bough, so that only an experienced hunter can tell it, while an inexperienced one will stand near by and see nothing.

When the Cossacks steal up to the pheasants, they pull their caps over their faces and do not look up, because a pheasant is afraid of a man with his gun, but more still of his eyes.

This is the way they hunt from under dogs. They take a setter and follow him to the forest. The dog scents the place where the pheasants have been feeding at daybreak, and begins to make out their tracks. No matter how the pheasants may have mixed them up, a good dog will always find the last track, that takes them out from the spot where they have been feeding. The farther the dog follows the track, the stronger will the scent be, and thus he will reach the place where the pheasant sits or walks about in the grass in the daytime. When he comes near to where the bird is, he thinks that it is right before him, and starts walking more cautiously so as not to frighten it, and will stop now and then, ready to jump and catch it. When the dog comes up very near to the pheasant, it flies up, and the hunter shoots it.

MILTON AND BÚLKA

I bought me a setter to hunt pheasants with. The name of the dog was Milton. He was a big, thin, gray, spotted dog, with long lips and ears, and he was very strong and intelligent. He did not fight with Búlka. No dog ever tried to get into a fight with Búlka. He needed only to show his teeth, and the dogs would take their tails between their legs and slink away.

Once I went with Milton to hunt pheasants. Suddenly Búlka ran after me to the forest. I wanted to drive him back, but could not do so; and it was too far for me to take him home. I thought he would not be in my way, and so walked on; but the moment Milton scented a pheasant in the grass and began to search for it, Búlka rushed forward and tossed from side to side. He tried to scare up the pheasant before Milton. He heard something in the grass, and jumped and whirled around; but he had a poor scent and could not find the track himself, but watched Milton, to see where he was running. The moment Milton started on the trail, Búlka ran ahead of him. I called Búlka back and beat him, but could not do a thing with him. The moment Milton began to search, he darted forward and interfered with him.

I was already on the point of going home, because I thought that the chase was spoiled; but Milton found a better way of cheating Búlka. This is what he did: the moment Búlka rushed ahead of him, he gave up the trail and turned in another direction, pretending that he was searching there. Búlka rushed there where Milton was, and Milton looked at me and wagged his tail and went back to the right trail. Búlka again ran up to Milton and rushed past him, and again Milton took some ten steps to one side and cheated Búlka, and again led me straight; and so he cheated Búlka all the way and did not let him spoil the chase.

THE TURTLE

Once I went with Milton to the chase. Near the forest he began to search. He straightened out his tail, pricked his ears, and began to sniff. I fixed the gun and followed him. I thought that he was looking for a partridge, hare, or pheasant. But Milton did not make for the forest, but for the field. I followed him and looked ahead of me. Suddenly I saw what he was searching for. In front of him was running a small turtle, of the size of a cap. Its bare, dark gray head on a long neck was stretched out like a pestle; the turtle in walking stretched its bare legs far out, and its back was all covered with bark.

When it saw the dog, it hid its legs and head and let itself down on the grass so that only its shell could be seen. Milton grabbed it and began to bite at it, but could not bite through it, because the turtle has just such a shell on its belly as it has on its back, and has only openings in front, at the back, and at the sides, where it puts forth its head, its legs, and its tail.