Young Thomas Grey

Peter Argonis

Young Thomas Grey

A Thomas Grey Naval Adventure

by

Peter Argonis

© 2024

Synopsis

At 11 years of age, Thomas Grey goes to sea as a volunteer in a small sloop of war, commanded by his father, to learn seamanship prior to joining the Royal Naval Academy. Thomas has to mature beyond his years, surviving sea battles and yellow fever, but he joins the Academy as an accomplished sailor and leader in the making, finding friends for life in the process.

Young Thomas Grey is the story of an 11-year-old boy joining the crew of a small British sloop of war during the latter years of the French Revolutionary War. Under the tutelage of his father, who commands the sloop, Thomas has to learn the ways of the sea, but also face the horrors of sea battles in wooden ships and of the lurking fevers rampant in the West Indies. Step by step, he earns the respect and even friendship of the ship's crew, but he also finds out the consequences of misbehaving.

When peace is declared, Thomas returns to England and briefly joins the crew of an old, laid-up battle ship that serves as flagship, Portsmouth, where the Commander-in-Chief notices him and recognises his potential.

Soon after, he joins the Royal Naval Academy, Portsmouth, as a scholar. He faces challenges there, both by older scholars and by the demanding curriculum, but soon emerges as a leader of his class and finds loyal friends. He must overcome the death of his beloved grandfather, but is also introduced to the ways of the flesh in a gentleman's club, the membership coming to him as a bequest from his grandfather.

When he graduates early from the Academy, he serves on the Commander-in-Chief's staff, now as a warranted midshipman, and repeatedly shows his worth to his superiors, until in late 1805, he returns home for a last leave before joining his next ship.

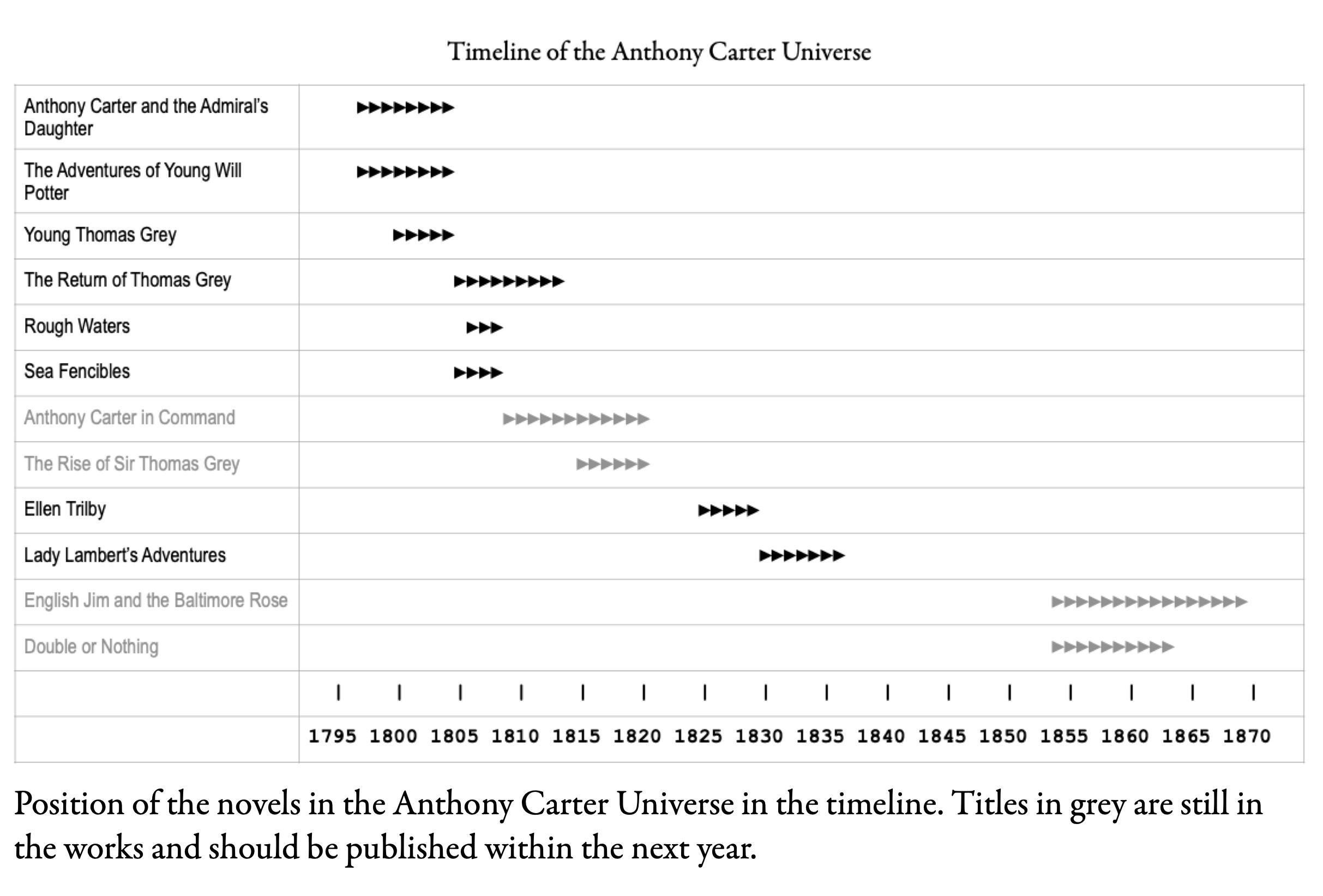

This is the prequel to the novel The Return of Thomas Grey, which, first published in serialised form in 2017, is also available at Bookapy in an adapted and revised form.

Table of Contents

Book 1: The West Indies

1. Going To Sea

2. People of Colour

3. The Convoy

4. The Ague

5. Tomcat

6. Cruising

7. The Squirrel

8. The Fair Sex

9. Austerity Measures

Book 2: Scholar

10. Volunteer Again

11. The Houghton Siblings

12. The Royal Naval Academy

13. Starting Classes

14. Fifth Class

15. Politics and Secrets

16. Country Life

17. 4th Class

18. Hail the Head Boy!

19. Home, Sweet Home

20. Night Watches & Other Issues

21. The Scots Vacation

22. 2nd Class

23. The Exams

24. Mister Midshipman Grey

25. A Welcome For a Hero

26. At Home

Cast of Characters

Appendix 1: Sail plan of a full-rigged ship

Appendix 2: Ranks in the Royal Navy

Appendix 3: Administrative Structure of the Royal Navy ca. 1800

Appendix 4: Rated and unrated ships and vessels

Appendix 5: Watches and times

Appendix 6: Gun salutes

Appendix 7: Nautical terms

Appendix 8: The Articles of War of 1757

Book 1: The West Indies

1. Going To Sea

February 1800

“Thomas, time for dinner. Wash your hands and put your shirt back in!” Mary could be heard.

Mary was the Greys’ housemaid and part of her duties were to keep Thomas clean and out of mischief. Young Thomas was unwilling to give up his toys for the formal supper downstairs. At his birthday, almost a year ago, he had received a beautifully carved and painted model ship, fashioned after one of the modern fifth-rate frigates, and just now, HMS Arethusa, 38, under her famous captain, Sir Thomas Grey, was fighting off pirates in the South Sea. He was loath to return to being ten-year-old Thomas Grey and to take supper with his family.

Thomas was an only child and living with his father and mother in his grandfather’s manor house outside Guildford. His father, Theodore Grey, was at home for a change. He had been 1st lieutenant in the Nymphe frigate, but she’d been paid off for repairs. He was at home now, waiting for his next orders. His mother, Margaret, kept his grandfather’s household and doted on her son whilst Theodore Grey was at sea, but reunited with her husband for once, she focussed on him, hoping against hope to have another child.

When Thomas had cleaned up and entered the dining room downstairs, he found his chair at his grandfather’s side, sitting opposite his father and mother, and being responsible for cutting his grandfather’s meat. Captain William Grey was old for his rank, over 60 already, and suffered from gout and rheumatism after a lifetime at sea. He had been posted as captain after the Battle of the Saints, almost 18 years ago, but his ship was paid off soon after, and he had been on half pay ever since, getting older and sicker. Still, the stories he told young Thomas about sailing the Seven Seas, about fighting French and Spanish men of war and even pirates, were the main inspiration for his playing, and he was fluent in sailor’s argot, even more so than in French, which a tutor tried to teach him twice a week.

The old man looked at his grandson with affection but also with a little sadness, before he said grace. The Grey household was not particularly religious, but the old captain had built a small chapel on his lands for the tenants and paid at least lip service to the Church of England.

A soup was served first, which Thomas ladled eagerly, for playing in his unheated room in the still chilly weather had cooled him off. For the main course, he diligently cut up the roast meat for his grandfather, whose left hand was rendered useless by rheumatism. He cut it up fine, too, for the old captain had lost many teeth to the scurvy1, back in the days before James Lind’s2 discovery of the antidote against the disease, lemon juice, was put to use.

“Good boy,” he smiled at Thomas. “Now listen up, Tommy, my boy, for the news your father has.”

A little surprised, Thomas looked at his father, a man who had played a very small role in his life so far, having been mostly at sea since the war had started six years ago.

“Yes, Thomas, I have news that will also affect you. I received my orders today. The Admiralty has given me the command over the Cormorant sloop3, a fine, full-rigged ship of sixteen guns, and appointing me a master and commander.”

Thomas nodded, understanding the significance. His father was now in command of his own ship and would be addressed as captain, even though he had not been posted to a rated ship. Even so, commanding his own ship was a big step for a man from the Surrey gentry.

“That is good, Father, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Thomas, that is good,” Theodore Grey smiled. “Has your grandfather told you when I joined the Royal Navy?”

Thomas nodded, the reason for the question dawning on him.

“Yes, Father, when you turned eleven. Can I join you in your new ship?”

The two men at the table smiled proudly, but Thomas could see that his mother was close to tears.

“Yes, my boy, I’ll take you in my crew. You’ll be rated a captain’s servant and you’ll answer to my steward. I’ll try to find our old wardroom steward, Tim Bartleby, and make him my steward. He’s a good man. In your spare time, you’ll take lessons with the bosun4 and the sailing master, to make a sailor out of you.”

“Sailing in a small ship will teach you well, Tommy,” Grandfather William smiled toothlessly, patting Thomas’s hand. “That’s how your father and I learned seamanship, and my father before me. You’ll do us proud, Grandson!”

Suddenly, Thomas remembered something. “Who’ll cut your meat, Grandfather, when I’m at sea?”

“One of the maids will, Tommy. It’ll never taste as good as when you do it, but I’ll be proud to know that you’re off serving our good King George.”

Finally, Thomas remembered his mother. She was clearly fighting her tears, and Thomas felt guilty.

“I’ll be good, Mother, I promise.”

“I know you will, my darling. I’ll miss you for certain.” She looked at his father. “Cannot it wait for another year, Theo?”

His father looked at her guiltily. “Better now, my dear. Once he has two years seagoing service, we’ll let him join the Naval Academy in Portsmouth, and he can be a midshipman at sixteen, a much better start than what I or Father had. You can visit him in Portsmouth and he’ll be home for the holidays whilst at the Academy. It is the best for his future.”

“I know that you only want the best for him. I shall get over it,” Margaret Grey sighed heavily. “How much time have we to fit him out?”

“Cormorant was laid up. I have to commission her, find a crew and have her provisioned. Two months on the outside; five to six weeks are more likely.”

“What uniform will he need?”

“None. He’ll be my cabin servant. White slops5, a pair of reefer jackets, sea boots, a warm watch coat, and some warm undergarments. The purser has a slop chest where we’ll find whatever else he might need.”

“What about my things, Father?”

“I am sorry, my boy. Your toys stay here. There will be no time for playing. Take along a book or two, but most of your reading will be books about seamanship, and you’ll have little idle time.”

Thomas nodded, understanding what his father was saying: his childhood was over.

—————

Time was flying in the next two weeks. Four weepy-eyed women assembled his clothing and a few possessions in an old, mahogany wood sea chest, his grandfather’s. His grandfather’s double-barrelled pistol with the beautiful cherry-wood stock was in that chest too, as was the old man’s dirk and sailor’s knife. Those weapons made it more than clear to Thomas that dangers beyond a fall from the old apple tree were in his future.

Mary, the servant, gave him a quick instruction in sewing and mending, and a small sewing kit to take along, another reminder of his new life, where he was responsible for his clothing. He also learned from Cook how to roast and grind coffee beans for his father, how to prepare a porridge, and how to fry eggs, not to forget how to clean a frying pan with water and sand. He would be his father’s servant, after all.

Young Thomas was kept so busy that he found no time for worrying, falling into his bed completely tired out every evening. Then, four weeks after that fateful supper, and after a tearful goodbye from his mother, his grandfather in his splendid captain’s coat took him into Guildford, and when the stage coach to Portsmouth left, the two of them climbed aboard. Two other Navy officers, a young captain of less than three years seniority and an elderly lieutenant were already sitting in the coach, and both greeted Captain Grey with the proper deference. Young Thomas, by contrast, was invisible to them, and that was fine with him, as he tried to be unobtrusive.

Arriving in Portsmouth in the late afternoon, William Grey led his grandson to an ale house for supper where Thomas had small ale with his half of a mutton pie. The food was rich and plentiful, and the atmosphere was distinctly naval. All around them, Navy officers and warrant officers were enjoying food and ale, and the conversations that flowed around the tables centred on the promotions after the Battle of the Nile and on the aftermath of the mutinies in the Channel Fleet. To a ten-year-old, this was quite daunting to understand, but William Grey explained things to him with great patience.

They spent the night in a fine inn close to the harbour and in the next morning, after a fine breakfast — Thomas cut his grandfather’s food likely for the last time — they walked to the waterfront, accompanied by a porter with a wheelbarrow and Thomas’s sea chest. From there, a four-oar jolly boat transported them out to where HMS Cormorant was lying at anchor and fitting out.

The sloop was already shipping her topmasts and topgallant masts, and the rigging was swarming with sailors bringing up the running rigging, as William Grey explained to his grandson.

“She’s a right smart looking ship, my boy, and your father should be proud of her. Eight gun ports to a side, and she’s mounting carronades on her quarterdeck and fo’c’sle6. Not bad at all, my boy! A little short of hands I’d say, but Theodore still has four or five weeks to collect more. You’ll do well in her, my boy.”

“Those masts, Grandfather, they’re really high!”

“Likely a hundred feet to the masthead, my boy. Over time, you’ll have to learn to climb up there to set sails and splice cordage. The bosun will teach you. Don’t worry; he’ll make sure not to lose his captain’s son,” the old man chuckled.

“I’ll try, grandfather. Is she carrying big guns?”

“Just six-pounders, my boy, pop guns, for the most. I reckon she’s also shipping twelve-pounder carronades. Those don’t count for her rating, but add weight to her broadside at close quarters.”

Over these explanations, the jolly boat had almost reached the sloop and was challenged.

“Boat ho!”

“Aye-aye!” the cox’n hailed back, lifting six fingers to signal the approach of a post-captain and causing quite a turmoil on the sloop’s deck. Careful not to ruffle feathers, William Grey waited until the crew stood ready before he ordered the cox’n to hook on. Thomas jumped up, eager to climb up the Jacob’s ladder, but a hissed command from his grandfather made him stop.

“Thomas, you’re just a ship’s boy now. Never enter through the port, and never ahead of an officer!” The old captain was all discipline now. “Wait here and climb aboard through a gunport, understood?”

Thomas understood. He stood straight, as much as the swaying jolly boat allowed, and rapped his first “Aye-aye, Sir!”.

“Good boy! Wait until the bustle dies down, then find your way on board.”

With that, he laboriously climbed up the ladder with his right hand only, but eschewing the bosun’s chair. From what young Thomas could see, six boys stood to both sides of the entry port whilst two pipes shrilled as Captain Grey came aboard and was greeted by his son and junior in rank.

“Welcome aboard, Sir,” Thomas heard his father say, but then a gun port opened and a friendly face peeked through.

“You the captain’s son, Thomas?” the face asked.

“Yes, Sir.” Thomas squeaked.

The man chuckled. “Just call me Bartleby. I’m your father’s steward. Give me a hand, and I’ll pull you up!”

Thomas did and quite unceremoniously entered his new life as a sailor. Bartleby stood there hunching a little, with the quarterdeck beams just five feet above the main deck.

“Come aft with me, my lad. You’ll sling your hammock with me and Clifton, the secretary. Where’s your dunnage?”

“Ah… still in the jolly boat, Mis… Bartleby.”

“Heya, lads, hoist up the boy’s chest, will you!”

One of the oarsmen complied, and Thomas dragged his sea chest aft, following Bartleby.

“Don’t scratch the deck, boy!” Bartleby hissed in alarm, but then he understood. “Too heavy, huh? Lemme give you a hand!”

With Bartleby’s help, Thomas was able to carry the heavy mahogany chest one deck below and then aft. There, just forward of the gunroom, the mess for the master’s mates and midshipmen, was a tiny cabin barely accommodating two hammocks, a foldable table and two stools

“We’ll put another hammock in here. You’re small, and it’ll fit. Clifton snores sometimes, but at least he don’t fart much.”

Thomas giggled over that, but he stowed his sea chest away and followed Bartleby up to main deck and then to the quarterdeck where they found William and Theodore Grey.

“Your new servant is ready, Sir,” he announced to Thomas’s father.

“Thank you, Bartleby. Where’d you find a berth for him?”

“With Clifton and me, Sir. He’ll fit in right fine, Sir.”

“Excellent! Once Captain Grey has left, show him to the cabin and explain his duties.”

William Grey took this as his cue.

“I had better return to shore, Theodore. Thomas, the best of luck for you. Learn your duties, my boy, and make your father and me proud. Oh, your father has your birthday gifts.”

“Thank you, Sir,” Thomas answered, aware that his grandfather was a lofty captain aboard a Royal Navy ship. He got his head patted in return.

“Now give your grandfather a hug, my boy!”

Thomas did and was surprised at the trembling the old man showed. Looking up, he saw tears in his eyes, and he felt a lump in his own throat.

“I’ll be good, Grandfather, I promise.”

“I know you will, Grandson. Theodore, look after him well and bonne chance with your fine ship!”

The two men hugged briefly, and then the old captain left the ship amidst the twitters of the bosun’s pipes. When he was gone, Theodore Grey pushed his only child aft and towards the cabin, with Bartleby following.

The after cabin in Cormorant was tiny, but the furniture and fixings his father had brought made it look cosy enough.

“This is where you’ll serve at first, Son. Bartleby will show you what to do. Mister Hanson, the bosun, will teach you seamanship whenever there’s time. When we’re at quarters, you’ll serve as powder monkey on the quarterdeck. This afternoon, I’ll have someone show you the ship from the quarterdeck down to the hold, so you’ll know your way to the magazine.”

“Aye-aye, Sir?” Thomas tried.

“When we’re alone, call me Father. Answer with aye-aye only when I give you an order, understood?”

“Yes, Father,” Thomas smiled with relief.

“I’m also here for you if something bothers you or if you are afraid, understood?”

“Yes, Father. Just not when we’re at stations, right?”

Theodore Grey laughed proudly. “We’ll make a tar our of you in no time, right Bartleby?”

“Aye, Sir. Will he eat with you, Sir?”

“Supper, yes, if possible. He should eat with his mess mates during the day and on watch.”

“Aye, Sir. Should I spread the word to curb the cursing?”

Theodore Grey looked at his son. “Did your grandfather teach you curses?”

Thomas grinned. “Aye, he bloody well did!” he answered cheekily, wisely starting with a mild swearword.

“He’ll learn to curse anyway,” Theodore Grey answered Bartleby’s question. “Another thing, Thomas: your mother told me that you were doing well in school?”

“Yes, Father. I can read and write. Grandfather made me read the London Gazette for him and the Surrey Herald, too.”

“What about your numbers?”

“I can count to a thousand, but I can add and subst… subtract, too. I can mol… multiply some.”

“That’s quite good already, Son. My secretary, Clifton, will teach you and the gunroom boys more reading and writing when there’s spare time for you and him. The purser will teach you calculating and the sailing master will show you how to shoot the sun. No doubt, the Academy will teach you some more, but you better join there with some knowledge already, and with seagoing time as well.”

Thomas swallowed quickly. There really would be no time to play anymore.

“I’ll do my best, Father.”

“I know you will. Go now and help Bartleby stowing the cabin stores!”

That was an order, Thomas knew, and he answered properly, “Aye-aye, Sir!”

—————

Over the next days, Thomas was busy learning how and where to do and find things. He also learned to ignore the taunts directed at him when he was outside the confines of the after cabin. He was the youngest person on board the Cormorant, but not the smallest. Two of the powder monkeys — ship’s boys — were both smaller and scrawnier than Thomas, who had never known real hunger, let alone starvation in his life, something his young shipmates knew well. He was also wearing better fitting clothes of good quality, making him stand out. Fortunately for him, he had not been tutored at home but had attended school in Guildford, and he had learned to give taunts as well as take them. He could also match those urchins swearword for swearword, courtesy of Captain William Grey’s private tutoring, something that amused the older sailors to no end, at least until the bosun, Mister Hanson gathered the ship’s boys, all eight of them, and showed them the knotted stick which he used on naughty boys’ behinds.

“Stop that mischief, or I’ll make you hug the gunner’s bride7!” he threatened. “You’re all shipmates, Cormorants even, and I’ll not let you pick on each other. Understood?”

Sufficiently cowed, they chorused their “Aye-aye, Mister Hanson”.

“Now sit down, and I’ll teach you the bowline hitch!”

Hanson produced some cordage and had them tie bowline knots, and when they mastered that, he added the running bowline and the French bowline. Bowline knots and eye splices were something Thomas had already learned from his grandfather, and he helped his shipmates with those tasks.

“How come you know them knots so good,” Willie Smith, a twelve-year-old boy asked him under his breath.

“My Gramps taught me since I was six.”

“He a sailor?”

“He’s a captain. Fought at the Saintes under Rodney. He’s old and stays at home,” Thomas whispered back, still repeating the running bowline.

“Gor blimey! You be a cap’n, too?”

“That or crab food,” Thomas answered with assumed bravado.

“Damn, you’ll be good. How’s your father as a cap’n?”

“Wouldn’t know; he’s been away all the time. He’s never drunk though and I reckon that’s good.”

“Aye, my old man, he’s mean when drunk. That’s why I runs away and joins here.”

“You, Smith and Grey, do your knots and keep a still tongue!” Hanson cut in.

“Yes, Mister Hanson!” both boys answered and kept their mouths shut afterwards. Still, when the lesson finished, they both nodded to each other before they tended to their tasks. Thomas went aft and was put to work peeling potatoes for his father’s supper. That finished, Bartleby sent him to find the purser’s steward, the petty officer who doled out provisions, to draw rations for the after cabin and the mess formed by Bartleby, Clifton and Thomas, but also the wardroom and gunroom stewards. Whilst Bartleby cooked the supper, refining the foods with herbs and other good things from the cabin stores, Thomas was tasked with setting the table in the cabin and with drafting his father’s ale for supper. When the food was ready, Thomas then served his father whilst Bartleby and Clifton ate their shares down in the small cabin. After serving the captain, Thomas was allowed to bring his own, smaller share of the supper to the table and to join his father.

They both ate with an appetite, but when they were finished, Thomas sat with his father for a few minutes to recount what he’d learned over the day. Finally dismissed, he collected plates and spoons to clean them with sea water. He then wiped the table with a wet cloth and readied his father’s cot for the night, fluffing the stuffed pillow and shaking out the blanket. This completed his duties for the day. Bartleby would handle the cabin duties until his father turned in, and Thomas could roll into his hammock for some much needed sleep. It was not to be.

"You remember what day is today?"

"M-monday?"

"You turned eleven today, Thomas. Happy Birthday, Son! Bartleby, bring in his gifts!"

Thomas was at a loss. He had been looking forward to his birthday for months, but with all the bustle and work, he had completely forgotten it. At least, Bartleby showed now with three boxes containing the gifts from his mother, father and grandfather — warm mittens, a book on seamanship, and a huge folding knife with a rosewood handle and a 5-inch blade. Best of all, Bartleby had found a real, sweet cake at a baker on shore and had made hot chocolate for them to celebrate. For the first time, Thomas felt real happiness on board the Cormorant.

—————

Finally, with the crew twelve under her complement of 125, Commander Grey took his ship to sea. The last additions to the crew had been fifteen convicts from Bodmin Prison, all of them landlubbers, and three men who had received Royal pardons after a court martial had sentenced them to hanging for mutiny. Mutineers or not, they had been able seamen and were badly needed, even though they had been disrated. Young Thomas, his head full of the stories he’d heard about the Great Mutinies of ’97, was afraid around them at first, but they did their duties better than most other men on board.

Weighing the anchor and setting the sails was as exciting as anything Thomas had ever seen, and he stood open-mouthed, watching as the sails filled and the small ship became alive. Cormorant had been decommissioned to receive the new fangled copper sheeting, protecting her against barnacles and the shipworm, and with her bottom clean and still shiny, she cut through the water like a smooth-skinned dolphin once her topgallants were set, too. Theodore Grey was standing by the wheel, issuing curt orders to the quartermasters, whilst the sailing master, Mister Browning took bearings of the landmarks along the coastline. The 1st (and only) lieutenant, Mister Duncan, a lowland Scot in his mid-twenties, oversaw the work in the rigging, but also the idlers on deck, as they heaved on the braces and bowlines to set the sails properly. A lot of things had to be done at once, and Thomas looked on in confusion.

Suddenly, he felt a hand on his shoulder. “Time to set the table for the Cap’n’s breakfast, my lad,” Bartleby reminded him. “Go and roast the coffee beans and grind’em, will you!”

Thomas nodded eagerly and found the coffee box, counting off twenty beans. Then he took a small iron pan and headed for the galley. The cook, Bill Cummings, made room for him, and Thomas held the pan with the coffee beans over the galley fire until they acquired a dark brown colour. Then he shook the roasted beans into his father’s mortar and carried everything back to the after cabin. Using the pestle, he set to work grinding the coffee beans into powder. Returning to the galley, he retrieved the copper kettle that Bartleby had set on the galley grille and, in the cabin, added the hot water to the coffee powder.

Next came fresh bread, bought the evening before, which he sliced, and blackcurrant jam, and when his father stepped into the cabin, with the ship on a temporary course, he could sit down to a finely laid table.

Since the hands only received two meals per day, forenoon and dogwatch, Thomas did not partake of this breakfast, but his father allowed him a mug of watered-down coffee with a spoonful of sugar as a reward.

Soon, it was time for the captain to tend to his ship again, and Thomas cleared the table, not without spooning an bit of the blackcurrant jam into his mouth and savouring the treat. His next task was to bring his father’s sleeping cabin to order, fluffing the pillow and hanging the blanket over a line to air out. The straw mattress was flipped over, and then his father’s second pair of sea boots needed shining with tallow. This done, he found his father’s and his own used shirt, soaked them in seawater, and proceeded to rub the dirt off them. Bartleby had to hang the shirts over a clothesline, the line being too high up for an eleven-year-old.

By then, it was eight bells in the morning watch8, and the purser’s steward doled out the rations. Thomas, as the youngest of their mess, collected the foods and brought them down to their shared cabin. One after the other, the three stewards and the secretary found their way down there, and they shared a hurried morning meal, washed down with already stale water from the barrels, but also with a small cup of tea brewed for them by the gunroom steward, Millner. The hierarchy was clear in their mess: Clifton was senior as captain’s secretary, Bartleby second, Morlake, the wardroom steward came next ahead of Millner, and Thomas was at the bottom. Yet, with Thomas being the captain’s son and servant, the other mess members took pains to be kind and helpful to him. He had to perform his tasks, sure, but there was no swatting him or harsh language if he made mistakes or forgot things.

After the morning meal, with nothing urgent to do, Clifton sat Thomas down on his sea chest at the small swaying table and had him spell words, simple ones at first, but then proceeding to nautical terms. There was not much for him to complain about, for Thomas knew his letters well for his age. Then, producing a smooth blackboard and chalk, Clifton dictated short sentences for Thomas to write down. If he misspelled words, Clifton had him write those sentences again. They continued that practice until the ship’s bell sounded four times, which ended the lesson, for Clifton had to tend to the reports he had to write.

By now, it was also time for Thomas to prepare the captain’s noon meal. Theodore Grey did not require much at this time of the days, but he certainly expected another jar of coffee, which was again Thomas’s task to prepare. More bread was sliced and Bartleby prepared cold cuts, to be served with bread slices, pickled gherkins and Durham mustard. The gherkins were pickled by Cook in the Greys’ manor house and tasted of home, and Theodore Grey allowed Thomas to set one aside for his own evening meal.

One thing that did not seem to bother Thomas at all was the motion of the ship, not even down below. He ate with a good appetite even when some of his newly recruited shipmates were hanging over the lee side, puking their hearts out. His main problem was visiting the latrines forward of the forecastle. Seeing his older, hairy shipmates as they emptied their bladders and bowels was intimidating to a boy of eleven. Their private parts seemed huge to him and threatening, and their crude talk and rough jests were something for which his grandfather had not prepared him. He often held in as long as he could, sometimes dancing on his feet with the need to relieve himself before darting forward. Obviously, Mister Hanson, the bosun, ever watchful, had noticed that and guessed the reasons, for overnight, the ratings curbed their language in the latrines when one of the ship’s boys were there. This did more than anything else to make life on board the Cormorant better for Thomas.

He and the other boys also bonded a little whenever their tasks left them time for skylarking. They also explored the rigging under the leadership of Tom Watkins, the eldest at thirteen years, with his voice breaking already. He hoped to become a top man soon, and he was nimble like one in the rigging already. At first, they only ventured to the main top, but gradually, they explored the upper reaches of the mast, too. Thomas learned to suppress the feeling of vertigo when perched on the topgallant yard, eighty feet above the deck, and to use braces and stays to make his way down again. Early on, in his exuberance, he glided down the mainstay too fast for the last feet, burning his palms fiercely, but he learned from that experience, and a month into their journey, he felt at home aloft.

Cormorant was headed for the Jamaica station, as they had heard, to replace a condemned sloop. To an eleven-year-old, this meant nothing at first, but sailing for weeks without sighting land, he began to understand just how far away Jamaica was. His father did his best to help him understand where they were headed, taking him to the chart room and pointing out their position on the charts every evening. He also learned about the prevailing winds from his father. What was hard for him to understand was that Earth was a great big globe suspended in the great nothing of space. This had not been a subject of his schooling at home, but Theodore Grey owned a globe, almost one and a half feet across, on which he taught his son about the planet on which they dwelt.

Then, five weeks into their passage, the lookout in the masthead yelled "Ship ho!"

When Mister Duncan, the 1st lieutenant, climbed aloft with a spyglass, he motioned for Thomas to come along. Up in the masthead, swaying in circles with the ship’s motions, Thomas could see the tiny speck of a topgallant sail on the horizon and he could watch as the speck grew out of the horizon and a second speck appeared. Suddenly, Thomas understood that they were sailing on a huge, curved surface as more and more of the oncoming ship was revealed to his eyes.

Suddenly, Mister Duncan took the spyglass from his eyes and hailed down to the deck.

“She’s a brig, Sir! Looks like one of our West Indiamen!” And then, “Let’s get down to the deck again, my lad, and be careful!”

Climbing down under the eyes of the 1st lieutenant was a little intimidating, but Thomas manfully eschewed the lubber’s hole in the top, taking the proper route over the futtock shrouds9 as was proper for an aspiring sailor.

With the ships closing in, the strange sail could soon be seen from the deck, and Captain Grey decided to use the opportunity for exercising the crew.

“All hands! All hands, clear the ship for action!” Mister Duncan hailed over the deck, and the small Marines drummer boy, just two years older than Thomas, appeared on deck and produced a pitiful drum roll that made Sergeant Carver of the small Marines detachment roll his eyes.

This was not the first such exercise, but it produced some chaos as the slow-witted amongst the new men had not yet learned their duties. Thomas, with the other ship’s boys hastened down to the magazine where the gunner and his two helpers loaded buckets with gunpowder cartridges for them to carry to their stations on the gun deck, the quarterdeck and the forecastle. Thomas received a bucket full of twelve-pounder cartridges for the four carronades on the quarterdeck and hastened up the companionways with it. He came just in time for the carronade crews to have finished uncovering and readying the short, squat guns on their sliding carriages. Each gun captain picked four cartridges, and Thomas was ready to bolt down to the magazine again if necessary.

By now, the hands were at their stations, the bulkheads all along the decks had been dismantled, and the yards aloft had been secured with chains. Cormorant was outwardly ready for fighting. Being on the quarterdeck, Thomas could see his father exchanging shrugs with Mister Duncan.

“We must practice that, Mister Duncan.”

“Aye-aye, Sir. Our three mutineers were quickest to ready their gun, Sir.”

“I noticed, Mister Duncan. Sometime soon, we’ll reinstate them to their former rating.”

“Yes, Sir. They’re good men, Sir, and they had reasons for their grievances.”

“No doubt, Mister Duncan. Now, what about that sail?”

“I reckon her to be a Kingston merchantman, Sir, likely out of MacNellis’s shipyard.”

“That’s how I read her, too. She could be a French prize though, so let’s load and run out the guns, if you please.”

“Gun captains! Load and run out!” Mister Duncan hailed over the decks.

Not every gun crew responded with equal alacrity, two six-pounders on the main deck even lagged behind by a minute or more, prompting the senior midshipman, Mister Hollings, into a furious tirade, and Thomas learned a few more swearwords.

The oncoming ship was now showing British colours and the correct recognition signal, but Theodore Grey ran no risk. With the guns loaded and ready to fire, he hailed the stranger with a speaking trumpet.

“Ship ho! Which ship, Sir?”

“Merchantman Rosalind, Captain James Whitney, eight days out of Kingston, cargo of sugar for London, Sir. What ship?”

“His Majesty’s Sloop Cormorant, Captain Theodore Grey. Have you sighted any ships, Sir?”

“No, Sir, nary a sail since passing Cuba, and only coasters before that.”

“Bon voyage to you, Sir!” the captain hailed back.

“And to you, Sir!” Captain Whitney answered.

“Let’s raise the bulkheads again, Mister Duncan. Make certain to have all the charges drawn.”

“Aye-aye, Sir.” Duncan nodded. With a crew of lubbers, extra care had to be taken to make certain that round shot and powder charges were pulled from the gun breeches. “Gun captains! Run in and unload the guns! Deck crews! Raise the bulkheads!”

It took even longer to return the ship to its normal state, but finally, the hands could draw their rations for the forenoon. Thomas was collecting back the cartridges from the carronade crews when he noticed that one of the cartridges had a tear, with gunpowder leaking out and onto the deck.

“Sir!” he addressed the junior midshipman, Wellard, who was in charge of the quarterdeck guns. “There’s powder on the deck, Sir.”

Wellard looked at his crews. “You there, Crewes, swab that up!”

Crewes, the man in charge of swabbing the gun breech after firing, used his wet sponge to clean up the deck whilst Thomas carefully placed the damaged cartridge in the bucket with the torn seam upwards before he descended to the magazine. Pointing out the damaged cartridge to the gunner’s mate, he delivered his bucket and climbed back up to the main deck, just in time to draw the rations for his mess. It was cold food only, for the galley fire had been doused during readiness, but bread and cheese tasted just fine after the exciting last hours.

When they’d all had their meal, Mister Hanson again collected the ship’s boys and some of the younger landlubbers — landsmen in Navy parley — for another lesson in practical seamanship. The boys and young men had already progressed to simple splices, but now Mister Hanson started to teach the long splice10, a difficult art but crucial for splicing the cordage of the running rigging which had to pass through the blocks without catching. It took until the next watch was called, but most of them more or less learned it, mostly less. To perform such a splice in the swaying rigging, in the middle of a gale, was still another story.

Six days later, Cormorant reached the Windward Passage, between Cuba to the West and Haiti to the East, one of the major sea ways from the Atlantic Ocean into the Caribbean. Commander Grey ordered heightened watchfulness, for this strait was where most of the British shipping was concentrated and hence, where privateers and enemy navy ships prowled on the British trade. Therefore, Cormorant sailed along the Haitian side under the reasoning that this was where British merchantmen sailed, seeing how Haiti was now in the hands of the rebellious former slaves under the leadership of Toussaint L’Ouverture and had no navy. They encountered two more merchantmen, but no privateers.

Finally, three days later, Cormorant sailed past Port Royal and into Kingston harbour. After anchoring, the captain took his small gig to report to the flagship which lay at anchor under the citadel. The crew was left behind under Mister Duncan to secure the sails and start with the few necessary repairs, whilst the purser, Mister Morgan, took the side boat to the shore to register his needs at the Victualling Yard.

Thomas was kept busy with cleaning up the after cabin, washing the captain’s bedding and his table cloth. Given that they would take freshwater soon, he was allowed to rinse the laundry in some of the precious freshwater, a rare luxury in a sailing ship, washing out the salt and reducing the moisture in the sheets and blankets.

He was kept busy this way whilst Bartleby prepared the captain’s dinner. The stern windows were opened to let what breeze there was air the cabin, but when the captain returned during the second dogwatch, he let Bartleby know that he had already dined with the commander-in-chief. Instead, they had to prepare the cabin for guests, as the captain had invited his wardroom for a council. Therefore, wines were fetched from the hold where they kept cool, and glasses were placed around the dinner table.

When the officers, led by Mister Duncan, entered the cabin, Captain Grey informed them of their new orders from Sir Hyde Parker, the commander-in-chief. Thomas, refilling the wine glasses, could listen in and learned that Cormorant would patrol the major sea ways in the region, namely Windward Passage and Mona Passage, protect British homeward bound convoys and hunt down privateers. They would be at sea constantly, the captain explained, and only return to Kingston to pick up convoys. Mister Duncan then asked if they were allowed to attack Spanish and French shipping, and the captain confirmed this. When the time came for the officers to return to their duties or the wardroom, Theodore Grey gave his son a smile.

“Did you understand everything?”

“Not all, Father. We’ll have to fight?”

Theodore Grey shrugged. “We may, but then again, we may never see an enemy. Only time will tell. Go below and sleep now. I’ll show you Kingston tomorrow.”

This would be exciting, Thomas decided. From Bartleby and other sailors, he had been told of the fruits and other fine foods offered in the town, and he was looking forward to those.

2. People of Colour

May 1800

Kingston in 1800 was an astounding city with over twelve thousand people living and working there. The vast majority of them were Black slaves working in the shops and households of their holders. There was also a sizeable proportion of free people of colour, freed slaves and their progeny, who plied their trades. Only one fifth of Kingston’s population were White people of English, Scottish and Irish descent. The colonial government was in Spanish Town, some six miles to the West, but Kingston was the heart of Jamaican commerce with its huge natural harbour and the numerous shops, taverns, and even a theatre.

As he followed his father who led him along one of the major streets, Thomas gaped at the colourful life around him. He had seen very few Black people — Negroes — in his life, just a few coachmen of visiting neighbours. Now he saw himself surrounded on all sides by dark-skinned men and women of all ages, offering fruits and other food to the passers-by, and he held on tightly to his father’s hand.

“Don’t be afraid, Thomas!” his father told him. “They’re just traders like the ones in Guildford, only they don’t get sunburnt as easily.” He chuckled with the last words.

“Should I buy something, Father?”

“Why not? Try a banana or a mango. They’re sweet and tasty. You never had one, had you?”

“No, Father. What’s a banana?”

They stepped closer to a fruit stand, and the youngish Black woman greeted them.

“A good mornin’ to you, Guv’ner. What’s your pleasure?”

“A hand o’ bananas, two mangoes and two coconuts for my boy,” Theodore Grey answered.

The woman collected the fruits. “Sixpence, Guv’ner.”

Whilst his father handed the woman the coin, Thomas collected the fruits. The mangoes, red and yellow, looked like strange apples, the bananas were deep yellow with blackish tips, but the coconuts were inedible, being entirely too hard to eat. Yet, the woman deftly took them and with a huge knife, hacked openings into them. Thomas watched as his father took one of those open nuts and poured a liquid into his mouth.

“Try it, Thomas. It’s coconut juice.”

Thomas followed the example and discovered that the strange liquid was indeed sweet and tasty. Borrowing the woman’s knife, the elder Grey split the nuts open to reveal a soft, white flesh inside from which he cut shavings with his knife. Using his own sailor’s knife, Thomas did the same and tasted the coconut flesh. It tasted strange but sweet and delicious.

Next, he was taught to peel a banana and eat it. It was even better than the coconut meat, and Thomas stuffed his mouth with the sweet fruit.

“See, Son, ’tis good fruit you find in these islands. I’ll tell Bartleby to buy a good supply for when we’ll sail again. Green mangoes keep for quite some time and bananas, too.”

Thomas nodded eagerly, unable to answer with his mouth still full with fruit.

“See, a sailor’s life isn’t all hardships. Let’s find a good tavern for a meal.”

After some walking and asking passers-by, they found the Anson inn, clearly a tavern catering to sailing men. Being a commanding officer, Theodore Grey was shown to a table in common room which was open to the street on one side. He ordered a pepper-pot for them and small ale. After the first bites, young Thomas thought his tongue and lips were on fire. He had never encountered the hot spices on the Caribbean, and even his eyes were watering. His father chuckled.

“It’s the custom here, my boy. Somehow the meats keep better when they’re spicy. You’ll get used to it.”

“But it’s burning, Father!”

“Flush your mouth with small ale, and it’ll go away,” the elder Grey chuckled.

They saw more of Kingston on a day that Theodore Grey had set aside to spoil his only son. They found a coffee house on the way back to the harbour where Thomas tasted his first chocolate. Alas, once back on board, Thomas found that nobody had done his work over this day, and he was kept busy until after darkness.

When it became clear that Cormorant would not be ready to sail for a few more days, the Greys visited Port Royal and Thomas saw the Royal Navy facilities, but also some of the sunk buildings of Old Port Royal. It was almost 100 years ago that most of the once thriving port city had disappeared when a devastating earthquake liquified the seemingly solid ground, and three quarters of the houses had been swallowed by the quicksand. Thomas learned of the bad reputation of Port Royal from his father, but also of the riches that were spent there on wine and loose women during the golden age of the buccaneer pirates. Thomas had no real concept of what a loose woman was, and Theodore Grey thought him too young for such a lesson.

They also stepped into a small shop bearing strange signs and decorations. It was, Theodore Grey explained, the home and practice of the famous Jamaican doctress and Obeya witch, Cubah Cornwallis. Even eleven-year-old Thomas saw that Cubah, a black woman about the age of his mother or younger, was beautiful in the way of her race and must have been more so when a young woman. Most importantly, she had a friendly, winning smile that made Thomas forget all his shyness. Theodore Grey showed her respect beyond his usual ways.

“A good day, Mistress Cubah,” he offered.

“Mister Grey! Pray, what ails you?” the healer answered in good English.

“Nothing, but I would like to buy some of your wound ointment and of your tea for sore throats. This is my son, Thomas, a volunteer in my ship.”

“Peace and health upon you, young Thomas,” Cubah smiled at the boy who felt compelled to bow to her, making her smile.

“I’m no highborn woman, my lad; no need to bow!” Looking at his father, she said, “He’s a good boy I wager, and polite.”

“My wife and I hold that all God’s children were created equal,” his father answered with a nod. He produced a small parcel. “Admiral Cornwallis tasked me to bring you this as a token of his fond memories11.”

Thomas could have sworn that the woman blushed under her dark skin, but she smiled.

“He is such a fine man. Now, my dear Mister … Captain Grey? … let me find a jar of ointment for you and some tea. The boy is healthy?”

“Yes, so far. He's had nary a cold the last years.”

The woman nodded. “He looks healthy and clean,” but then she went into the back of her shop to fetch the requested items, but when she returned, she gave Thomas a small piece of soap that smelt of flowers.

“Wash your face with it, and your peepee, my lad. Dirt and grime make you sick, so keep clean, you hear!”

Thomas blushed almost scarlet at the mention of his unmentionables, but his father laughed heartily.

“Good advice, Thomas. Remember it.”

—————

Again, Thomas had to work til sunset to complete his tasks for the day, but it had been another exciting day. In spite of his embarrassment, the black doctress had impressed him. She was so different from the stuffy Doctor Wallis in Guildford! She exuded vitality and goodwill whilst Wallis exuded only boredom. After he’d taken dinner with his father, he asked him how he knew her.

“It must have been ’94 or so. I was still the Nº2 in the old Proserpine frigate, and we escorted the Kingston convoy from London. I had caught a wood splinter under my skin, and it was festering. The old sawbones wanted to amputate, but Captain Courtland sent me ashore to Cubah. She only lanced the festering wound, cleaned it, and gave me of her wound ointment. A week later, my leg was good again. If it was me, I’d hire her to knock some sense into our ship’s surgeons. There was this apothecary from somewhere near Portsmouth who spent two months learning from her, Gutteridge was his name I think. He said she’s no witch, she just knows healing herbs and insists on cleanliness.”

“She seems nice, too.”

“Yes, she is, and very popular around Port Royal. Some fop of a planter wanted to cane her for some reason, but there were enough Navy men around to give him the caning.”

“But she’s free. Why would he…”

“Thomas, some of those planters see a black face and they think ‘slave’. It was bred into them. To hear some of them, you’d think they’re only doing lip service to the Christian faith. After all, our good Saviour was a Jew, and one of the Holy Kings was a Negro. Did the Holy Mother kick him out of the stable? I think not. To me, Cubah is a fine woman and to be respected, regardless of her skin.”

Thomas looked at his father with wide eyes. He had rarely heard him speak so fervently of a matter.

“But, Father, people say…”

“What people say is of no matter. People can be stupid, and they mostly just repeat what they were told by other stupid people. Son, to do the right things, you must search for the truth, not listen to others.”

“But I listen to you and Mum.”

“Yes, but once you’re grown, you’ll have to find your own truths. Your mother and I are not infallible; nobody is. You’ll make mistakes, too, plenty of them. What’s important is to admit your mistakes to yourself and to learn from them.”

“Yes, Father, I shall try.”

“And nobody can ask more of you, Thomas.”

This was a weighty lesson for Thomas, and he lay awake in his hammock for a while, thinking about his father’s words, before sleep came.

—————

Three days later, Cormorant completed the repairs and victualling and, with new orders from the admiral, set sail for a patrol of the Windward Passage. Things returned to normal for Thomas, and that was almost comforting to him after the exciting days in Kingston Harbour. His day was fairly filled with the tasks he had to perform, but also with the schooling he received at the hands of the boatswain, the purser and now even the sailing master.

The latter was very exciting for the eleven-year-old, for he was allowed to shoot the sun with the master’s sextant. One of the master’s mates, Peter Yates, showed him how to steady the instrument against the movements of the ship and then the master taught him and the midshipmen how to calculate their latitude. The Trigonometry was daunting for a boy who had received barely more than simple Arithmetics instructions at school, but he was making slow progress. He even repeated the calculations in the evenings with his father’s help.

Meanwhile, they were on a northeastern course, navigating the Westward Passage between Cuba and Hispaniola, looking for signs of privateers or even pirates, of whom a few were still prowling the Caribbean waters. Once they passed Cap à Foux, the western tip of Haiti, they headed for the Turks Island Passage.

At Cockburn Town on Grand Turk, they carefully picked their way through the reefs and to the anchorage. Fresh fruits were purchased, and Captain Grey contacted the local authorities to find out whether enemy shipping had been sighted. None had, and they went up anchor again with dawn’s first light.

From there, they set a course for Bermuda, an important way stop for ships from and to Europe, and recently being fortified by British Army garrison. There was even a small dockyard. Yet, Cormorant stayed for only two days, for her captain to acquire intelligence, and for her purser to acquire fresh produce cheaply.

Sails were set for the 1,000 nautical miles to the Bahamas, which took them over nine days in changing winds. The route through the Northwest Providence Channel and through Florida straits was another well frequented water way to the Northern Caribbean, and they continued westward to the Yukatan Channel between the Yukatan Peninsula and Cuba, before heading back to Jamaica without having sighted a single enemy sail.

This changed on their approach to the Cayman Islands. They sighted Grand Cayman and George Town early in the forenoon watch, and as they closed in on the city, a ship was leaving the harbour in apparent haste.

“Mister Duncan, all plain sail if you please!” Theodore Grey ordered immediately. “Quartermasters, two points to larboard!”

“Two points to larboard, Sir!” the senior quartermaster acknowledged, whilst the boatswain’s pipes called for all hands.

Within minutes, Cormorant almost doubled her canvas as she aimed to cut off the foreign sail.

“All plain sail, Sir,” Mister Duncan reported. “Shall we run out the stuns’ls, Sir?”

“Yes, please do so, Mister Duncan,” the captain answered calmly.

“On deck, Sir! She’s got three masts, mebbe 400 tons if that much, looks like a slaver, Sir!” the lookout hailed.

“Colours?”

“No, Sir, but she looks like a Dago.”

“Spanish slaver making business here, Sir?” Duncan asked.

“Quite possible. They didn’t expect a King’s ship to come from the West, I reckon,” Theodore Grey answered with a grin. English ships were far more likely to come from Jamaica, and that was probably where the islanders had posted their lookouts whilst engaging in illicit trading with the Spanish ship.

Slavers, as a rule, were fast, so as to minimise losses amongst their densely packed human cargoes during the passage from the Slave Coast. Yet, their crews were small, like most merchantmen’s, and their armament, whilst sufficient to repel attacks by African warriors, could not be heavy, either, due to the scarceness of crews. If Cormorant, with her crew of 117 and her 14 six-pounder guns and six carronades succeeded in cutting her off, the presumed slaver would have to strike.

Her larger crew also assured better manoeuvrability. As it turned out, the sloop caught up with her quarry rather quickly, due to her larger spread of sails and a by now well trained crew. Not two hours after sighting the vessel, the foremost six-pounder placed a shot across the bows, causing the Spanish captain to hoist and strike his flag in surrender. Cormorant then hove to to windward of the prize, her larboard guns run out and loaded, whilst the starboard gun crews tumbled into the cutter and launch to take control of the ship. Mister Duncan led the prize crew and reported back to Captain Grey after an hour. Thomas, standing with the quarterdeck carronades, heard him.

“She’s the San Augustino, out of Vigo, Sir. 340 tons burthen, twenty-eight crew, six eight-pounder guns, and still carrying eighteen slaves, seven men, eight women, and three young girls. He sold off most of his cargo at Santiago de Cuba, and he had sold eleven more in George Town, when we were sighted.”

“Eighteen slaves, you say?”

“Yes, Sir. The men are rather scrawny. They’re the leftovers it would seem.”

Theodore Grey sighed heavily. Returning those unfortunates to their native country was impossible, even if they could find out where that was, but what could be done with them in Kingston?

“I shall have to consult with the governor’s office, but I want to make it clear that they won’t be sold. I don’t hold with slavery.”

“Yes, Sir!” Duncan nodded emphatically. “Mayhap, they can find work with the free people of colour?”

“That would be best. Well, let’s transfer the captain and his mates over here, secure the prisoners and give her a prize crew. Eight men under a master’s mate, Yates I think. The slaves are still shackled?”

“Yes, Sir. We could free them, but the men might give trouble, scrawny as they are. Only …”

“Yes?”

“They’re hands, and we’re short of complement, Sir.”

“Press them into the service?”

“At least they won’t be slaves, Sir. We could split’em up amongst the divisions. There’s a fellow amongst the Dagos, Sir, he seems to know their lingo. He’s Dutch, and he might pick the Cormorant over a prisoner hulk. He could make’em understand, Sir.”

“If you think you can handle that, Mister Duncan, give it a try.”

“Thank you, Sir. I better set up things now, Sir. By your leave?”

“Go ahead, Mister Duncan!”

It was then that he noticed his son watching, and he gave him a short wink. Thomas felt very proud of his father in this moment. It was only later when he learnt that his father’s refusal to sell the slaves was to cost Cormorant’s company over £700, but from what he could understand, most of the hands agreed with his decision, also because the San Augustino would fetch three times as much. Bartleby explained to Thomas that she would find use as a merchantman for Kingston’s trade with England and would easily bring over £2,000 at auction, being only three years old and undamaged. As one of the ship’s boys — at quarters he was serving as a powder monkey — Thomas could expect half a share of the prize money.

Before long, Cormorant, with her prize flying the white ensign over Spanish colours, made course for Jamaica and Kingston, whilst the new landsmen — raw recruits — were coaxed into washing off the grime of two months chained to the slave deck, together with the Dutchman who had indeed chosen Cormorant’s crew over a Kingston prison hulk. Once that was accomplished, the distrusting men were given clothes from the purser’s slop chest and issued their first food rations. They must have been very starved, the way they wolfed down hardtack and cheese.

“Poor devils weren’t given any food by them Dagoes,” Jamison, the captain’s coxswain said with a shake of his head. He spit over the bulwark in disgust. Then he grinned. “We catch another Dago, we let them Black devils do the boarding.”

Mister Hanson shook his head. “Let’s see how they fit in. It’s a colossal nonsense to read’em in, without them understanding a single word. But them’s the regulations.”

“Aye, George, but ain’t regulations and nonsense the same?”

The men chuckled, but then they saw Thomas.

“You’ll learn that before long, too, young Master Grey,” Hanson promised.

3. The Convoy

July 1800

Once back in Kingston, the prisoners were transferred to the shore, and the San Augustino was given into the care of the prize court. To find places for the remaining women and children was a more complicated endeavour, but the chaplain of the Army garrison solved the problem, finding work for them in the kitchens of the governor’s household and the officers’ mess hall. They would get room and board, and when they had learned their duties, even a modest pay. One of the freemen serving the garrison church would guide them and teach them some rudiments of English. None of them had husbands, except one, whose husband had been sold in the Santiago De Cuba slave market. As it was, they were better off in the garrison kitchens than as enslaved labourers in the plantations.

The commander-in-chief, Sir Hyde Parker, was not too happy about setting those women free, but Theodore Grey could argue that none of them had been registered as slaves by a British magistrate and were natives of a country that was at peace with Britain. That was splitting hairs, but Sir Hyde could use it to formally justify the decision. The planters would not like it, but then again, Sir Hyde was not depending on their goodwill. He pointed out, however, that a commander, such as Theodore Grey, could ill afford antagonising the powerful Caribbean planter faction in Parliament.

Meanwhile, a convoy headed for London had assembled at Kingston Harbour, with ships from all the British possessions in the Caribbean. The huge size of Kingston Harbour was a decided boon for that purpose, but now it was time to sail, before the impending start of the hurricane season in August. Cormorant would be part of the escort, which was headed by HMS Veteran, 64, sent back to England for an overhaul. The Diamond, 38, frigate and Cormorant sloop completed the escort for the 52 West Indiamen and their valuable cargoes.

The convoy put to sea on July 17, 1800, and it took almost a day for all the merchantmen to clear the harbour mouth. Cormorant sailed first, forming the vanguard, and lay hove-to until mid-afternoon, when Diamond and Veteran sailed past Port Royal. Upon a signal from Captain Richardson of the Veteran, the convoy started close-hauled12 on an eastern course along the southern coast of Hispaniola. With the Black rebels controlling Haiti, the French part of the island, and the Spanish forces in Hispaniola, the eastern part, engaged in a bloody conflict with rebellious slaves, too, there were small chances of being accosted by privateers. Yet, the convoy sailed in a tight, three-column order, with the escorts maintaining their windward positions, and it took them five days to reach their turning point, the Isla de Mona at the entrance to the Mona Passage.

From there, they could sail with the full Northeastern Trade Wind, for a long, northwestern leg to the Carolinas on the American coast, where they could expect to catch the Westerlies of the Northern Hemisphere. It was the usual route for the homebound convoys, and Britain’s enemies knew it. The convoys sailed along the northern coast of Hispaniola and past the Spanish stronghold of Samana Bay, some 50 miles west of Mona Island, where Spanish privateers waited for British shipping. Those were smaller vessels but handy, and therefore, Cormorant was sailing a full five miles landward of the convoy to provide early warning of any attack and engage any ships out of Samana Bay.

Indeed, as they approached the bay, the lookout spotted two ships leaving the protected anchorage, a three-masted sloop and a two-masted brigantine.

“Mister Smith, signal to Commodore: Two enemy sail in sight.”

Midshipman Smith, the youngest of the three midshipmen, picked the flags from the locker whilst the signal mate cleared the mizzen topsail halliard. A few minutes later, the five flags flew out from the mizzenmast. The answer came promptly.

“Sir, Commodore to Cormorant: Engage enemy.”

“Very well, Mister Smith. Mister Duncan, beat to quarters if you please!”

Thomas had to swallow as he heard the drum roll. This was the second time Cormorant prepared for a possible action. Yet, seeing everybody running to their stations, he gave himself a nudge and ran down through the main deck hatchway to the orlop deck and from there, through another hatchway down to the handling chamber. His eyes took a few moments to adapt to the almost-darkness of the magazine. The six boys were lining up and were handed buckets filled with gunpowder cartridges through a water-soaked felt curtain, which prevented any sparks to get into the magazine. The gunner’s mates wore wetted felt shoes, too, Thomas knew, since cartridges and buckets sometimes leaked, and the wet felt rendered the spilled gunpowder harmless.

Up along the companionways and to the quarterdeck, Thomas hastened through the milling mass of men manning their stations, and he reached ‘his’ carronades in time for their crews to load the first charge. He only had a short moment to look around before being sent down again, but he could see that his father was aiming to engage the larger of the Spanish ships. Then, he was on his way to the handling chamber again, running past the Marines sentry who guarded the companionway to the orlop deck to prevent men from seeking safety in the hold.

Down, in the dark, illuminated by two tallow lights in horn lanterns, the ship’s boys then waited for the first shots to be fired and for the order to bring more gunpowder. Thomas already knew that this was done since their purpose was to bring up the charges but whenever possible to stay out of harm’s way until they grew up to be sailors.

After what seemed like an eternity, the din of the discharging guns filled the lower decks, the sharp reports of the six-pounder guns and the duller roar of the carronades, but also the squeaking sounds of gun mount trucks as guns rolled backwards against the breech ropes. Then, distinctly, the sounds of splintering wood.

“Them Dagoes are firing back!” Willie Smith whispered.

“Sure they are. Dagoes are mean as snakes, but brave fighters,” Tom Watkins added his wisdom.

Just then, the next thunder rolled over the deck above them, and a voice yelled down: “Fresh charges!”

The gunner’s mates handed filled buckets through the felt curtain, and the boys hurried up to their stations as fast as they could, carrying their loads. When Thomas reached the main deck, he saw the headless body of a man leaning against the foot of the main mast. Swallowing heavily and trying to suppress the urge to run back down, he ran up to the quarter deck instead. There was his father near the wheel who spared him a short nod. “Good lad! Keep going!”

Thomas made the round to the four carronade crews, and when his bucket was empty again, he could not resist a quick look over the nettings. The Spanish ship did not look so neat anymore, with her foretop gone and her mizzen sail flapping uselessly in the wind, its gaff shot away. They might be winning. Then he rushed down the companionway to the main deck, but before he reached the hatchway, the Spanish ship fired again, and all around Thomas, the cannonballs crashed into the timbers of the sloop. Right before his eyes, a sailor cried out in agony, a two-foot-long, jagged piece of wood sticking from his right thigh. Without thinking, Thomas dropped his bucket and gave the wounded man his shoulder to lean on. Fortunately, he was only a slight man. They slowly made their way down the companionway to the orlop deck, whilst on the main deck, the six-pounders were firing back. Down on the orlop deck, Thomas helped the sailor forward to where the surgeon and his mates were tending to the wounded. Two of the surgeon’s mates received the man and, without ado, laid him on the blood-stained planks on which the surgeon performed his grisly duty.

“Hey you, back to your duty!” one of the mates yelled at Thomas who quickly ran down to the magazine, the screams of the sailor in his ears, just in time for the next charges being handed out.

Three more times, Thomas carried fresh charges to the quarterdeck before the orders came to cease firing. A moment later, the hurrahs of the crew filtered down to the lower decks, and the boys grinned at each other in relief.

Even with the Spanish striking their flag, Theodore Grey kept his crew at stations until proper control of the prize was established. Diamond had chased off the smaller privateer, and the convoy continued on its way whilst hasty repairs were effected on Cormorant’s decks and rigging. The prize, named El Halcón, The Falcon, also underwent repairs. The Spanish prisoners greatly outnumbered whatever prize crew Cormorant could send and were therefore distributed between the three escorts, who would share in the prize monies anyway, having been all in sight at the surrender.

Finally, the tired and hungry crew raised the bulkheads again and Cormorant returned to normal. This meant even more work for Thomas and Bartleby, since clearing the cabin for the engagement had left disorder and dirt all over it. It also took time for the galley fire to get going again, and as a result, Thomas was only able to serve dinner to his father at the start of the evening watch13. By this time, he could hardly stand on his feet anymore, but he manfully stood until the captain turned into being his father.

“Sit down, Thomas, and eat. Mister Wellard told me how you helped Wilkerson down to the surgeon in the middle of the fighting. The surgeon cut that splinter out from the leg. Wilkerson’s a good man, and we hope that’ll be fine again soon.”

“I… I had to help him, Father. He was screaming with pain.”

“Yes, these wounds hurt badly. His messmates saved their tots14 for him, and when I visited the sickbay, he was sleeping.”

“I hope he'll get better.”

“One just cannot tell,” Theodore Grey sighed. “We’ll have to wait and see. Now, have some of that meat! We must not starve you.” After a moment, he raised his voice. “Bartleby, I think this young man deserves a small mug of the ale.”

“Aye-aye, Sir, that he does. I’ll be right back, Sir. Some more ale for you, Sir?”

“I believe that to be justified,” Theodore Grey smiled, and when Bartleby placed the filled mugs on the table, he raised his and toasted his son. “To your first battle, Son. May you always escape unharmed!”

Thomas took a sip. It tasted a little bitter, but not too bad. The taste was stronger than the small ales he had been allowed to drink. “Thank you, Father. You, too.”

“Yes, it would be hard for either of us returning home to your mother without the other.”

“Shall we take the prize to London?”

“Those are the commodore’s orders. It’s always good to return to port with a prize, and Captain Richardson has not had much luck with prizes so far. It’ll do us good.”

Helped by the half pint of ale, Thomas was out like a light as soon as he rolled into his hammock, and he slept a dreamless sleep until shaken awake by Bartleby.

“Four bells, my lad. Let’s get the captain’s breakfast going!”

And so another day dawned for Thomas and the other hands in the Cormorant sloop. By six bells, the captain’s breakfast was served, and Thomas tidied up his father’s night cabin whilst the captain enjoyed his coffee. Then there were two shirts to wash, sea boots to shine and the tin plates to clean.

When he thought he was done, Mister Hanson called the ship’s boys together for another lesson. It was then that Thomas noticed that Willie Smith was not with them. Tom Watkins noticed Thomas’s look.

“Sick bay. ‘E’s got ‘is arm broken. Falling block hit ‘im.”

“Damn!” Thomas cursed under his breath, but the boatswain heard him.

“Yes, damn, young Thomas. Young Willie was hurt yesterday, but the sawbones thinks he’ll be all right again. He and you all bravely did your duty, and I’m right proud of you. Watkins, you did good filling in on the main top. I’ll talk to Mister Duncan about making you a top man after this journey. Grey, that was good thinking to bring Jimmy Wilkerson to the sawbones. All of you, I saw that you were scared with all that iron flying around your heads, but you served the gun crews as you were taught. We’ll make true tars out of all of you in no time. Well, that is if you ever get the long splice right, so let’s practice that!”

Thus followed an hour practicing all the splices they’d learned so far until the ship’s bell sounded six times, and they were released to claim their morning rations. As Thomas stood in line for his mess, one of the former mutineers, Tim O’Leary, clapped a heavy hand on his shoulders.

“Jimmy Wilkerson says ‘thank you’, young Thomas Grey. He’ll be a while healing he says, but that’s better than going down to Davy Jones’s Locker, like Billy Gorran yesterday.”

“He… he was hurt. I only gave him a shoulder to get down to the surgeon all right,” Thomas answered modestly. It really was not such a big thing.

“Aye, but me and Al Burton and old Jimmy, we’ll have your back from now. You’re a fine lad, a right chip off your old man's, err… the Captain’s block, and we’ll see to it that you’ll get home to your Mum in one piece.”

“Th-thank you, M… Tim?”

“Yes, mate, Tim’s me name, and you can call me that.”

—————

Over the next days, Thomas could feel the difference. Until then, he’d not been noticed by the able seamen, being just a boy of eleven and a cabin boy at that. Now, when he went about his tasks, he often got nods and winks from the older sailors. So did Tom Watkins who had stepped up aloft in a pinch during the fighting.

As they sailed in northerly direction now, the sick bay was emptying slowly. As a testament to their hardiness and in spite of the poor repute of Mister Jordan’s dexterity with saw and knife, not one of the wounded succumbed to their wounds, and after six days, even Wilkerson could be seen, doing light duty on deck, and limping about with a crutch. He, too, thanked Thomas for his help in an idle moment and affirmed the promise of support and protection made by O’Leary. In turn, Thomas helped the limping man when he drew the rations for his mess.

Of course, this situation was noticed by the captain, but he saw nothing wrong with his son becoming accepted amongst the crew, and the three pardoned mutineers were by now valued ratings. He often saw his son sitting with them as they patiently taught him the finer points of splicing cordage, mending sail cloth, and soon even ways to defend himself with his grandfather’s sailor’s knife, and he approved of that. Often, Tom Watkins was included in that group, and the captain was determined to make the oldest ship’s boy a seaman upon their arrival in London.

Fifteen days after their action off Samana, the convoy picked up the westerly winds, and from then on, they logged a steady six to eight knots as they started to cross the northern Atlantic. It was testament to the vastness of that ocean that they encountered only one sail during the crossing, and that was an American schooner headed for Baltimore. The Americans were still pitted against revolutionary France in what was known as the Quasi War, and the American captain readily related the situation in the English Channel.

Seven weeks after sailing from Kingston, the lookouts spotted Ushant15 Island at the mouth of the English Channel, and the Navy escorts assumed their readiness positions to windward of their charges whilst the merchantmen now sailed in a compact, three-column formation, heading for the English South Coast at first, and then for the Strait of Dover. They frequently encountered British shipping, but none of the French privateers were making an attempt on the convoy, allowing them to safely proceed through the Strait. Still using the westerly wind, the sailed northward then past Deal and Ramsgate, before beating to westward. At Sheerness, they anchored for the night, waiting for the morning tide which allowed them to proceed up the Thames River up to Gravesend. After that, the convoy disbanded with each captain making his way upriver and to where they planned to unload their respective cargoes.

The Navy ships sailed to Deptford with the next tide where they anchored. For the next hours, the hands cleared the rigging and the decks. Royal Marines sentries were posted on deck to prevent desertion — their crew comprised mostly pressed men — and an anchor watch was detailed. The rest of the crew had the afternoon and evening to themselves.

At six bells in the next morning watch, the crew mustered on deck in divisions and Theodore Grey announced the promotions. Several of the landsmen were rated seamen, and so was Tom Watkins, who was inordinately proud of it. Thomas was happy for his friend. To their utter surprise, Tim O’Leary, Jim Wilkerson and Albert Burton were re-rated as able seamen, their former rating before their trial and conviction, giving young Thomas another reason to be happy.

Tim O’Leary, as their speaker, answered for them. “Thank’ee, Sir. We promise you won’t rue this, Sir!”

“I know you won’t, men. You’ve shown it already,” the captain answered with a nod.

Jim Wilkerson, still quite unable to climb the rigging with his damaged leg was also appointed sailmaker’s mate whilst one ageing sailmaker’s mate — his eyes had become too weak for needle work — would start as cook’s mate into their next journey.

Back in the after cabin, Thomas was tasked with writing letters to his mother and grandfather. They would not be able to travel to Guildford during their stay in London. There were repairs to perform on the ship, reports to write, and people to see. The cabin stores had to be renewed, and both Thomas and his father needed some new clothing. Wines, too, had to be found, and some better cheeses for entertaining fellow officers.

In the afternoon, the Spanish prisoners were landed under guard and handed over to the shore authorities. The Crown paid a £5 premium for every captured or killed enemy sailor, and that money would go to Cormorant alone, £32 for Commander Grey and a little over 7 shillings apiece for the ratings, or one night of fun as Tim O’Leary laughed.

The El Halcón herself would be taken over by a prize agent after a prize court condemned her, and then sold to the highest bidder, unless the Navy Board opted for buying her. It would take a year or more for the money to materialise, but even divided by three, it would be considerably more than the head monies.

Theodore Grey also wanted to visit the Admiralty with his report of the successful action against the El Halcón privateer, always in the hope that there was need for a new post-captain in the Navy. Captain Richardson of the Veteran had given full credit to Cormorant for the capture, and this seemed to be an opportune moment to vie for a post ship16.

There was not too much time, with the next Kingston-bound convoy slated for early October, leaving them just three or four weeks at anchor in London. At least they would avoid the tail end of the hurricane season, generally considered the months of August to October, after which cyclones became rare.

With all the work, refitting and restocking the cabin, Thomas was kept busy enough, but a few times, he was allowed to accompany his father to the shore and to see the astonishing sights of London, the palaces and great houses, the parks, the imposing St. Paul’s cathedral and the ancient Westmister Abbey.

They also visited the shop of Reeves of Birmingham, sword makers, where his father’s sword would be given a makeover. The sword had been a gift from Thomas’s great-grandfather, Captain Roger Grey, on the occasion of Theodore Grey reaching commissioned rank, and the blade was of the best Birmingham steel. Making use of the opportunity, Thomas was gifted a dirk, a real, double-edged fighting knife with a hand guard and a sturdy, twelve-inch blade. He was admonished not to wear it on board, except when at quarters, for it was the side-arm of a midshipman.

Thomas was also with his father when he visited the Admiralty, asking for an interview with the First Naval Lord’s staff. Thomas had to wait outside, and when his father came out again, not twenty minutes later, he could see the disappointment in his eyes.

“Damn sugar barons,” was his only comment, and Thomas did not dare to ask for the meaning of that.